1. Introduction

Campidanese Sardinian,Footnote

1

spoken throughout the southern portion of Sardinia (see Mensching & Remberger Reference Mensching, Remberger, Ledgeway and Maiden2016 for a general overview of the linguistic situation in Sardinia), presents an intricate pattern of spirantisation and lengthening. Descriptively, word-initial voiceless [p t ʧ k] and voiced [b d ʤ g] are realised as stops when in initial and post-consonantal position, while the voiceless class alternates with spirants [![]() ] in intervocalic contexts. Complicating this description is the fact that [p t ʧ k] sometimes lengthen intervocalically, and [b d ʤ g] also sometimes spirantise.

] in intervocalic contexts. Complicating this description is the fact that [p t ʧ k] sometimes lengthen intervocalically, and [b d ʤ g] also sometimes spirantise.

The distribution of stops in Campidanese thus exhibits a dual patterning where both voiced and voiceless stops are subject to allophony, but the context and outcomes of that allophony seem to resist generalisation. In very broad terms, stops are subject to a pattern of alternation, but the rule C → [+cont] / V __V does not make the correct predictions, since the surface intervocalic context can produce both spirants and geminates. This thorny problem has been a perennial issue in the literature (see Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 165 and Molinu Reference Molinu1999: 169), with some ejecting the pattern entirely from the remit of phonology (Katz Reference Katz2021).

In this article, I argue that the pattern of lenition and fortition in Campidanese is phonological. The key is an analytical approach which can generalise over patterns that are phonetically arbitrary and unnatural – an approach that reveals the perfectly orderly character of Campidanese lenition and fortition. In short, the intervocalic context is a superficial description that misses several important generalisations which come out only after careful inspection of the phonological system and the structure of Campidanese. This analysis shows that there are in fact two complementary intervocalic contexts, phonologically speaking, distinct in their prosodic structure (§4.2). While voiceless stops spirantise in prosodically weak positions and are thus subject to a true process of lenition, voiced stops only spirantise when there is an empty timing position to their left: a prosodically strong position that produces phonological gemination in both voiced and voiceless stops.

The analysis developed here shows that an explanation for lenition and fortition in Campidanese can be provided if the representational account is adequate. This is in opposition to any surface-oriented view of strength and weakness, where the nature of the output is the final arbiter of what constitutes weakening and strengthening. In such views, any spirant realisation of a stop, for example, is weakening. In Campidanese, a surface-oriented view engenders a number of acute problems, given that describing all cases of phonetic spirantisation as phonological lenition cannot do justice to the pattern observed. Campidanese thus presents an interesting case study for Substance-Free Phonology (SFP) (Hale & Reiss Reference Hale, Reiss, Burton-Roberts, Carr and Docherty2000a,Reference Hale and Reissb, Reference Hale and Reiss2008; Reiss Reference Reiss2003, Reference Reiss, Vaux and Nevins2008, Reference Reiss, Hannahs and Bosch2018), since the output of weakening and strengthening in stops is partially neutralised to voiced fricatives, and phonetic cues are not reliable in the discovery procedure.

In the substance-free analysis developed here, explanation is derived through a theory of explicit representations, both melodic (segmental) and prosodic (suprasegmental). On the prosodic side, I use Strict CV phonology (Lowenstamm Reference Lowenstamm, Durand and Laks1996; Scheer Reference Scheer2004b, Reference Scheer2012) – a development of Government Phonology (Charette Reference Charette1990; Harris Reference Harris1990; Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud1990; Harris & Kaye Reference Harris and Kaye1990) – to provide a representational structure which explicitly defines contexts for both lenition and fortition. On the melodic side, I suggest that segmental representations in Campidanese are substance-free indices of natural classhood which contain no phonetic information but are available to phonological computation (see Dresher Reference Dresher2014; Odden Reference Odden2022).

The article is organised as follows. First, in §2, I conduct a brief overview of definitions of strength and weakness that view each as being essentially reducible to surface properties of the output of fortition and lenition, respectively. In §3, I lay out the facts of obstruent distribution in Campidanese, highlighting a disjunctive pattern of lenition and fortition. I show that the intervocalic context produces the same effect on target segments, meaning that an inspection of the phonetic facts cannot explain the pattern. Next, in §4, I show that the dual patterning of stops in Campidanese can be understood in phonological terms as a difference in representational structure on the prosodic tier. I then provide a substance-free account of the melodic content of segments in Campidanese, in order to show in §5 how these two domains interact with phonological computation and the interface between phonetics and phonology. The result is a straightforward account of both lenition and fortition in Campidanese.

2. Strength and weakness as properties of phonology

2.1. Substantive conceptions of strength

The vast majority of lenitionFootnote 2 and fortition patterns are phonetically natural. For example, when a stop lenites, it typically is realised as a more sonorous allophone, while the reverse is true in cases of fortition. That is, there is an apparent lack of invariance between phonological processes of lenition and fortition and the phonetic cues of those processes. In the case of Campidanese, the assumption that this invariant relationship should hold contributes to the argument by Katz (Reference Katz2021) that lenition and fortition in Campidanese are not phonological, being instead phonetic effects produced by syntactically determined prosodic domains and the influence these have on the expression of segments.

This is the logical endpoint for any surface-oriented view of lenition and fortition, where strength qua fortition depends on phonetic cues, including, for example, ‘duration, intensity, voicing and degree of formant structure’ (Lavoie Reference Lavoie2001: 8). Surface-oriented views of strength have been argued for by Fougeron & Keating (Reference Fougeron and Keating1997: 3737) and Bybee & Easterday (Reference Bybee and Easterday2019: 270–273), among others. Likewise, weakness qua lenition is manifest as a reduction in articulatory effort (see Kaplan Reference Kaplan2010 for an overview), a position which has been amply espoused in the literature (Bauer Reference Bauer1988; Bybee & Easterday Reference Bybee and Easterday2019; Kirchner Reference Kirchner1998, Reference Kirchner2000; Kaplan Reference Kaplan2010; Lavoie Reference Lavoie2001). Lenition, in this light, is a deterministic, sequential process – operating diachronically or synchronically – which results in a reduction of articulatory effort (Bauer Reference Bauer1988). Voicing of intervocalic stops, for example, happens because devoicing in that context would require extra effort to stop the glottis from vibrating (Westbury & Keating Reference Westbury and Keating1986; Kingston & Diehl Reference Kingston and Diehl1994).

Bauer (Reference Bauer2008: 622) argues further that lenition can only be understood in terms of phonetic properties, as it is distinct and untethered from positional identifiers: if lenition is defined in uniquely environmental terms, for example, V

![]() $\_$

V, a generalisation is missed since there is a unity to processes of lenition in their ‘failure to reach a phonetically specified target’. In this view, the substantive properties of lenition outweigh any positional effect. The most that can be hoped for is that position ‘can be seen as one of the influences on what phonetic changes are likely to occur’ (Bauer Reference Bauer2008: 619).

$\_$

V, a generalisation is missed since there is a unity to processes of lenition in their ‘failure to reach a phonetically specified target’. In this view, the substantive properties of lenition outweigh any positional effect. The most that can be hoped for is that position ‘can be seen as one of the influences on what phonetic changes are likely to occur’ (Bauer Reference Bauer2008: 619).

However, phonological theory as a theory of competence is not about what is likely or probable (cf. Newmeyer Reference Newmeyer2005: 104), and I argue that the pattern of alternation in Campidanese (§3) shows two things:

-

1. A model of phonology needs some way of showing positional effects (syllabic effects) in patterns of lenition and fortition.

-

2. Positional effects cannot be reliably understood in phonetic terms.

That is, a non-phonological analysis of Campidanese strength and weakness entails a loss of generalisation (see §3.2), but surface properties – articulatory or temporal – cannot be used to reliably identify strength and weakness: these can only be understood in phonological terms.

2.2. Strength and weakness in substance-free phonology

If a theory of lenition and fortition is viewed as more than just a catalogue of phonetic correlates, it can potentially provide an explanatory connection between the effects of lenition and fortition and the contexts in which they are observed (Cyran Reference Cyran, Carvalho, Scheer and Ségéral2008: 448). Following Szigetvári (Reference Szigetvári, de Carvalho, Scheer and Ségéral2008: 124), this article aims to meet three goals:

-

1. Provide a simple definition that enables the analyst to decide whether or not any phonological phenomenon is lenition.

-

2. Give a clearly defined set of contexts where what is categorised as lenition is ‘natural’ to happen.

-

3. To correlate the change and the contexts, showing that it would be ‘unnatural’ if lenition occurred elsewhere.

This approach is ‘substance-free’ (Hale & Reiss Reference Hale and Reiss2000b, Reference Hale and Reiss2008; Reiss Reference Reiss, Hannahs and Bosch2018) in that there is no primitive assumption made about how strength and weakness should be expressed phonetically. Indeed, I argue that it is impossible to make any conclusions about strength or weakness based solely on the phonetic properties of phonological output – the principal diagnostic tool is phonological behaviour (Gussmann Reference Gussmann2004; Kaye Reference Kaye, Broekhuis, Corver, Huijbregts, Kleinhenz and Koster2006; Odden Reference Odden2013).

Put another way, lenition and fortition are always driven by position (see also Honeybone Reference Honeybone, Nevalainen and Traugott2012).Footnote 3 In this view, strength and weakness are relative – strong items are strong only relative to an item in a weak position. How strong items are realised phonetically is determined at the interface, not by universal fortition scales. This substance-free approach makes predictions about what is weak and what is strong based on the position of each in prosodic structure.

Lenition is thus not a metaphorical term as such, but rather describes a phonological process that applies in a specific context, resulting in a weaker segment in that the output contains fewer phonological primes than the input (see also Harris Reference Harris1990, Reference Harris1994; Harris & Lindsey Reference Harris, Lindsey, Durand and Katamba1995). In this view, lenition can have only one definition: any process which removes melodic primes in a phonologically weak position, regardless of its surface output. This characterisation of weakness is phonological, since it says nothing about the phonetic exponence of lenition. This article argues that the pattern of alternation in Campidanese between voiceless stops and fricatives entails the loss of melodic primes in specific prosodic positions, and is thus true lenition.

The representation of strength adopted here is equally phonological: it is defined by position and syllabic structure. Any segment which is associated to two positions on the skeletal tier is strong. Consequently, since doubly-associated voiced geminates are phonetically expressed as short voiced spirants, surface-oriented correlates for strength are unavailable. The unexpected conclusion of this view is that the process of spirantisation which targets voiced stops is a result of fortition in which the melodic material associated to a single timing position becomes associated to two (see also Lai Reference Lai2021a: 85). This analysis reveals a surprising and novel fact: the outcome of fortition processes can result in an increase in sonority, meaning that surface-oriented views of phonological strength and weakness are inadequate.

3. Strength and weakness in Campidanese Sardinian

3.1. Some words on the data

The patterns described in this article come principally from the description in Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998). They were confirmed as part of a fieldwork project conducted by the author and Simone Pisano in and around the village of Genoni, in the province of Sud Sardegna, located on the high plain of the Giara di Gesturi in south-central Sardinia in mid-February 2020. Guided conversations were conducted with 23 inhabitants of Genoni, all of whom were born and raised in the village or nearby. The interviews were conducted in Sardinian by two native speakers. All participants were adults, between the ages of 36 and 91, and native speakers of Campidanese with a high level of competency and strong judgements about grammaticality. For many of these participants, Campidanese is their first language, though all are bilingual in Campidanese and Italian. All of them regularly and reliably produced the patterns described below.

3.2. The empirical situation: Spirantisation and lengthening

In external sandhi (cf. Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 36ff.), when morphology results in the voiceless stops [p t ʧ k] being realised intervocalically,Footnote

4

the result is a surface spirant at the same place of articulation [![]() ] as in (1), which shows citation forms as they would be realised in isolation or following a consonant-final word, along with the same forms in intervocalic contexts.

] as in (1), which shows citation forms as they would be realised in isolation or following a consonant-final word, along with the same forms in intervocalic contexts.

Where the voiceless stops are concerned, this pattern is systematic and invariable – it is predictable and has no exceptions. In this intervocalic context, there is a critical difference in behaviour between the voiceless series and the voiced stops [b d ʤ g]. While they may be dropped entirely, as in (2), the most frequent outcome for voiced stops is simply to surface unaltered.

Whether a voiced stop is realised as the zero form, however, is not predictable, since the alternations in (2) are optional: for example, /su bentu/ may be realised as [su bentu] as well as [su entu]. Elision of voiced stop drops depends on several things. First, it is subject to a register effect, being more likely in slower, careful speech (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 36ff.). Critically, it is also subject to lexical exceptions (in particular borrowings; see Lai Reference Lai2020), and some words, such as those in (3), never show elision of the voiced stop.

Even in northern varieties of Sardinian where elision is systematic, only words from the native lexicon undergo it; recent loanwords do not show any weakening (Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b). Since the pattern of voiced stop allomorphy depends on morphological idiosyncrasies, it does not seem to be a property of the phonological grammar, and I do not treat it further here.

Complicating this pattern is the fact that there are intervocalic contexts in which voiced stops, like the voiceless stops, alternate with spirants, as in (4):

A further complication is the fact that voiceless consonants can be realised as long on the surface rather than undergoing spirantisation, as in (5):

Voiceless stops thus exhibit a duality of patterning in the intervocalic context, spirantising as in (1) but lengthening as in (5). In traditional terms, these two surface output patterns correspond to weakening and strengthening, respectively. In sum, the surface pattern of Campidanese stops presents several disjunctions, with intervocalic voiced stops variously surfacing faithfully, deleting or spirantising, and intervocalic voiceless stops either spirantising or lengthening.

Simple observation of the conditioning environment of these alternations does not provide any explanation – indeed; it obscures the generalisation: there are two distinct phonological contexts in play. These contexts do not depend on surface properties; rather, they are active at a more abstract level of structure (§4). The first environment triggers lenition of voiceless obstruents; it is the ‘true’ intervocalic context, represented in structural terms as VCV. The second environment triggers lengthening of voiced stops and spirantisation of voiced stops; it is the ‘false’ intervocalic context, because despite its surface properties it contains an abstract consonantal position, and is represented in structural terms as VCCV. Each context is entirely predictable, and each process is phonological.

3.2.1. Lenition

The pattern of allophony targeting voiceless obstruents in word-initial position in Campidanese is typically described as weakening or lenition (Wagner Reference Wagner1950 1997; Virdis Reference Virdis1978; Contini Reference Contini and Andersen1986; Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998; Mensching & Remberger Reference Mensching, Remberger, Ledgeway and Maiden2016; Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b). Lenition is a descriptive term used to refer to the process which produces alternations of the kind in (1) – it does not as yet have any formal, theoretical status in this analysis. The primary ambition of this section is to lay out the facts concerning lenition in Campidanese, so that the disjunctions pointed out in §3.2 can be given a phonological explanation.

In (1), it was shown that lenition targets stem-initial voiceless stops in intervocalic contexts. The same position also triggers lenition of the fricatives /f s/, manifested as voicing, as in (6):

Lenition also operates on the first member of stop–sonorant clusters, as in (7):

In this same context, /l/ is also in an allophonic relationship with [ʁ] (or sometimes [ʕ]; see Molinu Reference Molinu2009), as in (8):

Since this alternation has the same structural description as those in (1) and (6), following arguments from Kisseberth (Reference Kisseberth1970) concerning the functional unity of phonological rules, I will consider all these alternations to be the result of a singular process of Lenition, which must be given formal status (see §5.3). The categorical nature of the alternation’s structural change, which affects both manner and place of articulation in a seemingly arbitrary way, requires an abstract phonological analysis that does not depend on phonetic facts (Chabot Reference Chabot2021; Scheer Reference Scheer, Honeybone and Salmons2015).

3.2.2. Lenition in non-sandhi positions

The word-medial position merits some discussion regarding the effect of Lenition. In this position, there are no alternations, but the distributional facts show a preponderance of spirants and voiced fricatives: [zriβɔ̃ĩ] ‘wild boar’, [di![]() u] ‘finger’, [fo

u] ‘finger’, [fo![]() u] ‘fire’. Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998) and Lai (Reference Lai2015b, Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b) argue that these are the result of lexicalised sound changes, and not the result of synchronic lenition as in (1). Lai (Reference Lai and Russo2015a: 275) provides the most explicit argument to this effect, suggesting that since word-medial obstruents in items such as [proku] ‘pig’ are not realised as spirants, it shows that by the time the diachronic process of metathesis which changed Latin porcu

u] ‘fire’. Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998) and Lai (Reference Lai2015b, Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b) argue that these are the result of lexicalised sound changes, and not the result of synchronic lenition as in (1). Lai (Reference Lai and Russo2015a: 275) provides the most explicit argument to this effect, suggesting that since word-medial obstruents in items such as [proku] ‘pig’ are not realised as spirants, it shows that by the time the diachronic process of metathesis which changed Latin porcu

![]() $>$

ˈporku

$>$

ˈporku

![]() $>$

ˈproku was completed, any synchronic rule of lenition had already ceased to be productive.

$>$

ˈproku was completed, any synchronic rule of lenition had already ceased to be productive.

Synchronically, this position introduces a number of difficulties. The first is that it establishes an active synchronic process which targets only word-initial onsets in intervocalic contexts, while word-medial onsets in the same context are spared. The second is that it introduces a number of phonemes, including /![]() /, which are distributionally limited to the intervocalic context, the very context which targets stops for spirantisation and fricatives for voicing. This includes /z/, which is not a phoneme in Campidanese (Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b: 606), since per Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998: 28) it does not occur in absolute word-initial position. Words such as [kazu] ‘cheese’ suggest that there is an underlying /s/ which is being voiced, thus an active process of lenition targeting intervocalic obstruents. The same is true of words with suffixes such as 3sg in /pappa-t/ ‘to eat 3-sg’ or the plural /-s/ as in /faula-s/ ‘lies’, where the final morpheme of each form may surface with a following epenthetic copy vowel, such that they appear as [pap:a

/, which are distributionally limited to the intervocalic context, the very context which targets stops for spirantisation and fricatives for voicing. This includes /z/, which is not a phoneme in Campidanese (Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b: 606), since per Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998: 28) it does not occur in absolute word-initial position. Words such as [kazu] ‘cheese’ suggest that there is an underlying /s/ which is being voiced, thus an active process of lenition targeting intervocalic obstruents. The same is true of words with suffixes such as 3sg in /pappa-t/ ‘to eat 3-sg’ or the plural /-s/ as in /faula-s/ ‘lies’, where the final morpheme of each form may surface with a following epenthetic copy vowel, such that they appear as [pap:a![]() a] and [fauʁaza], respectively. Assuming that [z] and [

a] and [fauʁaza], respectively. Assuming that [z] and [![]() ] are not contrastive segments in Campidanese, their presence in these forms can be explained if they are the result of Lenition of /s/ and /t/, respectively.

] are not contrastive segments in Campidanese, their presence in these forms can be explained if they are the result of Lenition of /s/ and /t/, respectively.

A grammar that generalises over the facts in §3.2 while ignoring word-medial intervocalic voiceless obstruents is significantly more complex, with a rule of lenition that distinguishes between external sandhi (V#.CV) and word-internal intervocalic contexts (V.CV), along with an increase in the size of the phonemic inventory. If the rule that targets word-initial obstruents in external sandhi is also active in word-medial position, the rule itself is much simpler, and the distribution of spirants can be easily accounted for within the phonological grammar.Footnote 5 This is an application of the Free-Ride Principle discussed by Zwicky (Reference Zwicky1970), where non-alternating forms are assumed to be subject to an active phonological process in a grammar (see Krämer Reference Krämer2012: 41–42 for discussion). For this reason, this analysis considers Lenition to be active in word-medial positions. I will take up the case of [proku] and its representation in §3.2.4.

3.2.3. Non-targets of Lenition

Lenition does not target all obstruents in Campidanese. As discussed in §3.2, voiced stops may variably be reduced to zero in this context, but unlike /p t ʧ k f s l/, which are always targeted by Lenition when in the proper context, voiced stops show variation, with a number of lexical exceptions in which they never delete. Furthermore, the voiceless fricative /ʃ:/ and the voiceless affricate /ʦ:/ never undergo Lenition, even when in the proper context (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 33), and the same is true of /dz/, /v/ and /ɖ:/ (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 39). The nasals, /n m ɲ/, never lenite in external sandhi: [su niu] ‘the nest’. Word internally, /n/ does seem to lenite, but only when following the main stress-bearing vowel (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 26). Given the essential role played by stress in the structural description of N-deletion and the fact that there are no alternations in intervocalic positions created by sandhi, this process is not the same as Lenition, and is not treated here.

3.2.4. Resistance to Lenition: Virtual Geminates

Recall that one of the arguments against synchronic word-medial Lenition is that words such as [proku] do not have word-internal spirants (Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b). I argued in §3.2.2, however, that the same process of Lenition that targets word-initial obstruents in external sandhi is in fact active in word-medial position. In this section, I argue that gemination is a manifestation of strength in that geminate stops never undergo Lenition.

In order to understand why Lenition does not target voiceless stops in words such as [proku], consider the data provided by Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998: 149) in (9), in which voiceless obstruents are realised in surface forms:

Immediately, what stands out in (9) is that all of the lenition-resisting objects are realised as phonetically long. However, in Campidanese, the status of phonemic geminates is uneven: only for the sonorants /r n l/ does phonetic length always correspond to an underlying contrast between geminates and singletons (Virdis Reference Virdis1978; Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998). Phonemically long obstruents are variable and may be realised as short. For sonorants, Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998: 161) provides some near-minimal pairs as in (10), though the deletion of /n/ and its effect on vowels makes the contrast between ‘hand’ and ‘big-msc.’ less obvious:

The contrasts in (10) suggest that geminate structure is active in the phonology of Campidanese. Lai (Reference Lai2015b, Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b) notes, however, that for all other obstruents in Campidanese phonetic duration is not contrastive. Even in words such as those in (9), geminates may be realised as phonetically short, meaning that duration is not a reliable correlate for geminacy in Campidanese (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998; De Iacovo & Romano Reference De Iacovo and Romano2015).

While it seems obvious that an increase in phonological timing should result in an increase in phonetic duration, phonological timing is above all a matter of phonological representations (see Davis Reference Davis, Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011 for discussion), and many factors related to performance can impact the manifestation of timing as duration (Clements Reference Clements, Wetzels and Sezer1986: 39). In Italian, for example, length is not always the primary phonetic correlate of gemination (Payne Reference Payne2005, Reference Payne2006). Geminates that are not expressed as phonetically long are what Ségéral & Scheer (Reference Ségéral, Scheer and Dziubalska-Kołacyk2001a: 311ff.) refer to as virtual geminates, objects that are associated with two positions on the skeleton, but whose surface realisation is identical to a corresponding singleton.Footnote 6

With no phonetic correlate on the consonant itself available for identifying phonological geminates, they can only be identified through phonological behaviour. The principal characteristic of geminates is that they never lenite (see Jones Reference Jones, Harris and Vincent1988: 321 and Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 33).Footnote 7 Geminate resistance to Lenition is a manifestation of Inalterability (Hayes Reference Hayes1986), a structural property inherent in geminates that protects them from Lenition. Since words such as [mak:u] ‘crazy’ never undergo Lenition, regardless of the phonetic length of the medial consonant, they must be geminate (see also Barillot & Ségégral Reference Barillot and Ségégral2005; Barillot et al. Reference Barillot, Bendjaballah and Lampitelli2018 for a comparable case in Somali). Whether a voiceless stop is realised as long or short does not affect its phonological status: speakers perceive them as the same object.

This suggests that any word such as [proku] which does not manifest surface length but which resists Lenition is a virtual geminate and that this fact must be discoverable by language learners. In the case of [proku], for example, the resistance to lenition of word-medial stops is enough for learners to recover geminate structure – the underlying form /prokku/.Footnote 8 The result is a phonological geminate, which is not realised with phonetic length, recoverable through its resistance to Lenition.

3.2.5. Fortition

As shown in (2), in the intervocalic configuration which triggers spirantisation of voiceless stops, voiced stops never spirantise. However, (4) exhibits a pattern of alternation in which voiced stops do in fact spirantise. This is what Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998) calls ‘pseudo-lenition’, and what Katz (Reference Katz2021: 657f.) refers to simply as lenition.

I argue that spirantisation of voiced stops is not lenition in the phonological sense, but rather is the result of a process that targets voiceless stops as well, for which I will provisionally adopt the term Fortition. The effect of Fortition is most apparent where voiceless stops are concerned, since they are generally realised with phonetic length. Ultimately, I will argue that Fortition affects voiced stops, as well as voiceless stops, fricatives and sonorants, though only members of the latter must be realised with phonetic duration. Unexpectedly, voiced stops are realised as spirants when subject to Fortition. This will be shown through the examination of three related contexts in which Fortition is active in Campidanese. What unifies the three contexts is that in each, there is an empty timing position to the left of the targeted segment.

The first context to consider is word-initial following a final stop in a preceding word, such as the plural marker /-s/ or the 3sg verbal marker /-t/. In such cases, the final obstruent does not surface as a coda, and instead triggers either the insertion of a paragogic copy vowel if realised, or subsequent lengthening of the word-initial stop if elided (Contini Reference Contini and Andersen1986; Jones Reference Jones, Harris and Vincent1988; Molinu & Pisano Reference Molinu, Pisano, Rainer, Russo and Miret2016; Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b). In the description given by Jones (Reference Jones, Harris and Vincent1988: 322), in such circumstances, initial consonants are ‘reinforced’ or given a ‘geminate pronunciation’. Indeed, Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998: 190) sees this as a fortition manifest as surface gemination, and provides the following examples:

The examples in (11) represent a subcase of Fortition, which I will refer to as compensatory lengthening. Lai (Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b) calls this a synchronic process of fortition, by which an obstruent /p/ is realised with increased length [p:], as in (11a). The same is true of fricatives, as in (11b).

When a voiced stop is realised in parallel contexts, the result is a spirant, as shown in (11c). What (11) and (4) show is an interesting dual pattern: in compensatory lengthening contexts, voiceless stops geminate, while voiced stops spirantise.

The second context of Fortition in Campidanese is fed by a process of metathesis. Diachronically, metathesis characterises the evolution of Latin to Sardinian generally (Molinu Reference Molinu1999), but its effect was particularly salient in Campidanese (Virdis Reference Virdis1978). Lai (Reference Lai2013, Reference Lai2014, Reference Lai and Russo2015a) identifies three kinds of metathesis, each of which affects the rhotic phoneme /r/:

While (12a) and (12b) are diachronic processes, (12c) is active synchronically in words that begin with a vowel and are disyllabic: VrCV (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 419). This process is key for understanding how Fortition works in Campidanese, and for what it tells us about prosodic structure and the synchronic lenition process (13):

As /r/ moves into the branching onsets shown in (13), it suppresses the realisation of the initial vowel in the article, and triggers lengthening of following voiceless stops (13a) and spirantisation of following voiced stops (13b), a dual patterning which parallels (11).

The third context of Fortition occurs after certain vowel-final prepositions and connectives which have lost an etymological final consonant in diachrony (Jones Reference Jones, Harris and Vincent1988): for example, /a/ (

![]() $<$

ad or aut) ‘to/at’, /ɛ/ (

$<$

ad or aut) ‘to/at’, /ɛ/ (

![]() $<$

et) ‘and’, /nɛ/ (

$<$

et) ‘and’, /nɛ/ (

![]() $<$

nec) and a handful of others. Lengthening is thus triggered by unstressed monosyllables with etymological coda consonants (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998; Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b). The lost etymological consonant is what Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998) refers to as a ghost consonant, since it appears to mark the context for a certain subset of Fortition processes. As in some other languages of Italy, this appears to be a kind of Raddoppiamento fonosintattico (RF).Footnote

9

That is, following Fanciullo (Reference Fanciullo1986: 67), an initial consonant is realised as geminate if immediately preceded by an item specified in the lexicon to trigger RF, as in (14):

$<$

nec) and a handful of others. Lengthening is thus triggered by unstressed monosyllables with etymological coda consonants (Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998; Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b). The lost etymological consonant is what Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998) refers to as a ghost consonant, since it appears to mark the context for a certain subset of Fortition processes. As in some other languages of Italy, this appears to be a kind of Raddoppiamento fonosintattico (RF).Footnote

9

That is, following Fanciullo (Reference Fanciullo1986: 67), an initial consonant is realised as geminate if immediately preceded by an item specified in the lexicon to trigger RF, as in (14):

RF is common to all varieties of Sardinian and represents a kind of strengthening (Contini Reference Contini and Andersen1986). In RF, as in compensatory lengthening, there is a dual pattern: voiceless consonants are realised as geminate (14a), while voiced consonants are realised as spirants (14b).Footnote 10

3.2.6. Summary of the empirical situation in Campidanese Sardinian

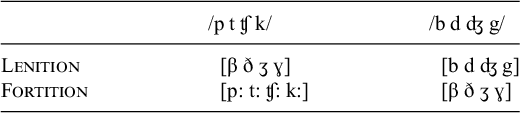

To summarise, Campidanese is characterised by a process, Lenition, which spirantises voiceless stops but does not target voiced stops. There are three processes, however, which do produce spirantised voiced-stop realisations: compensatory lengthening triggered by the loss of a preceding word-final consonant (11c), compensatory lengthening induced by metathesis (13b) and RF (14b). In addition, these latter three processes all result in lengthening of voiceless stops, and so I refer to all three processes as Fortition. The pattern of lenition and gemination is schematised in Table 1.

Table 1 A summary of spirantisation and lengthening patterns in Campidanese Sardinian.

Considering the distribution of spirants and stops in Table 1, there is a direct link between the context of lengthening in voiceless stops and spirantisation in voiced stops. Fortition, then, which results in /p t ʧ k/ being realised as geminate, also involves phonological gemination of /b d ʤ g/, despite their phonetic realisation as spirants. To suppose otherwise is to interpret as an accident the fact that RF, compensatory lengthening and metathesis-induced compensatory lengthening all have complementary scope over voiceless and voiced stops. I argue they are the result of a singular process of strengthening which is reflected in prosodic structure (§4.2).

In a surface-based approach (cf. Katz Reference Katz2021), this conclusion is surprising, since spirantisation is a classic case of lenition. Kirchner (Reference Kirchner2000: 510) suggests that spirant realisations of geminates are suboptimal and violate constraints which select output candidates for articulatory ease as well as perceptual faithfulness, and therefore can never be selected by a grammar.Footnote 11 This is no doubt what leads Bolognesi (Reference Bolognesi1998: 165) to argue that voiced stops spirantise precisely because ‘they cannot give rise to geminate structure’, as voiced postlexical geminate structures are ill-formed. In order to prevent the grammar from producing such structures, Molinu (Reference Molinu1999: 169) imposes a constraint on the grammar which blocks voiced geminates in postlexical phonology, arguing that the RF process which produces geminates in Lugodorese instead gives rise to ‘variantes non-géminées et spirantisées’ in Campidanese. That is, a spirant is explicitly not a geminate, since a constraint in the grammar interdicts the gemination of voiced obstruents. An equivalent constraint blocks gemination in the analysis of Katz (Reference Katz2021: 666).

I argue that this is a classic case of ‘substance abuse’ (Hale & Reiss Reference Hale and Reiss2000b, Reference Hale and Reiss2008) – a misuse of the phonetic facts in the building of the analysis. This has two unfortunate results in Campidanese. The first is the loss of generalisation entailed by analysing spirantisation and gemination in a disjunctive way as a function of the output. The second is the bloating of the synchronic grammar in order to prevent voiced stops from geminating. The solution to these problems, I argue, is to recognise that compensatory lengthening, metathesis-induced compensatory lengthening and RF produce geminate structures from all stop inputs, voiceless and voiced alike. The correct view is to analyse all three Fortition processes as a singular, unified process that results in a phonological geminate, resistant to Lenition as revealed by voiceless stops and surfacing as spirants in the case of voiced stops. This conclusion discards entirely the phonetic properties of the segments in question, and emerges only from consideration of phonological structure and behaviour.

Following a general principle established by Hyman (Reference Hyman1970), the advantage of positing such abstract structures is the explanatory value they provide:Footnote 12 patterns of spirantisation and gemination are the result of two prosodic effects, one of Lenition and one of Fortition. Lenition is a melodic process that targets voiceless stops in a weak prosodic position, triggering the loss of melodic material. Fortition is a prosodic effect that spreads melodic material and results in phonological gemination in all cases. The result is a unified analysis of strength and weakness in Campidanese, summarised in Table 2. In this view, both weakening and strengthening are still metaphorical notions – their formal status is in their prosodic representations, and how each process falls out from prosodic structure (§4).

Table 2 A summary of positional effects in Campidanese Sardinian.

The facts in Campidanese suggest some notion of phonological weakness inherent in the context that conditions obstruent lenition, and strength inherent in the context that resists the lenition process. That is, weak contexts allow lenition, and strong contexts produce geminate structure. The observation that segments that resist Lenition are geminate does not, in and of itself, constitute an explanation for their exceptional status – it merely recapitulates the distribution of stops and spirant allophones – nor does it satisfy the requirements for a theory of lenition (see §2.2). To do these things, an adequate theory of phonological representations and computations is required.

4. Representational structure in Campidanese Sardinian

4.1. The representation of timing positions

The examination of the empirical situation in Campidanese (§3) reveals an intricate pattern of spirantisation, lengthening and resistance to spirantisation. In this section, I will elaborate an analysis of the prosodic structure of Campidanese which shows this pattern can be understood to fall out from the effects of phonological computation in different phonological configurations. I argue that there are two processes at work, which I have called Lenition and Fortition. Lenition is a phonological process that works on melodic representations, but which crucially depends on the prosodic structure as a part of its structural description. Fortition is a phonological process which spreads melodic material by associating it with two timing positions, producing geminate structure.

Here, singletons are represented as a single melodic segment associated with a single timing position (15a), while geminates are represented as a single melodic segment associated with two timing positions, as in (15b):

Any autosegmental theory (Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli and Pulleyblank1994; Clements Reference Clements, Wetzels and Sezer1986; Clements & Keyser Reference Clements and Keyser1983; Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith1976, Reference Goldsmith1990; Lowenstamm & Kaye Reference Lowenstamm, Kaye, Wetzels and Sezer1985) with a skeleton can build structures like those in (15). The objective here is to make a connection between the structural associations of segments to timing positions in the skeleton and how phonological computation is influenced by them, thus satisfying the second requirement for a theory of lenition discussed in §2.2, as well as providing an explanation for the facts in §3.2. The basic intuition is one based on phonological strength and weakness, where a segment being associated with two timing positions results in prosodic strength through Fortition, making that segment immune to Lenition.

The analysis thus presents two levels of phonological representation, one prosodic and one melodic. I will begin by outlining the level of prosodic representation, with a particular emphasis on how prosodic structure interacts with Lenition and Fortition, staying entirely within a phonology that is agnostic as to phonetic substance.

4.2. Prosodic representations

To show this, let us first consider what kinds of syllabic positional strength effects are attested cross-linguistically. Ségéral & Scheer (Reference Ségéral, Scheer, Carvalho, Scheer and Ségéral2008b: 135) provide a schematic view of the various configurations of consonant and vowel sequences and their characteristic positional strengths, reproduced in Table 3, which suggests that three different positions need to be distinguished. The first is the word-initial and post-coda position, which is a position of strength. In Campidanese, this strength is manifest in the power to license the realisation of the full set of phonemic obstruents, as well as resistance to Lenition, as seen in all citation forms in §3.2. This protected position,

![]() $\{$

C,#

$\{$

C,#

![]() $\}$

$\}$

![]() $\_$

, has been dubbed the coda mirror (Ségéral & Scheer Reference Ségéral and Scheer2001b; Scheer Reference Scheer2004a; Ségéral & Scheer Reference Ségéral, Scheer, Carvalho, Scheer and Ségéral2008a; Scheer Reference Scheer2012).

$\_$

, has been dubbed the coda mirror (Ségéral & Scheer Reference Ségéral and Scheer2001b; Scheer Reference Scheer2004a; Ségéral & Scheer Reference Ségéral, Scheer, Carvalho, Scheer and Ségéral2008a; Scheer Reference Scheer2012).

Table 3 Five positions of strength and weakness (Ségéral & Scheer Reference Ségéral, Scheer, Carvalho, Scheer and Ségéral2008b: 135).

The second is the internal coda and final coda position, a position of weakness. Coda weakness is manifest in Campidanese as severe restrictions on what segments are licensed in that position.Footnote 13 In lexical forms, the full set of possible codas is /r/, /s/, /t/, a nasal consonant homorganic for place with a following consonant, and the first element of a geminate (Jones Reference Jones, Harris and Vincent1988; Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998; Molinu Reference Molinu1999; Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b). Generally, /s/ and /t/ codas are the result of morphology, as in, for example, plural nouns or 3sg verb endings. On the surface, however, /s/ and /t/ either trigger the epenthesis of a copy vowel identical to the final vowel in the stem, as in /kanna-s/ [kan:a-z(a)] ‘reeds’, or are deleted in final position, as in (11). In turn, /r/ is subject to a number of processes of metathesis which means its distribution as coda is restricted to word-medial position in a limited number of lexical items, as in the examples in (13). This leaves the set of surface codas limited to word-medial /r/, /s/ in s+C clusters, homorganic nasals and the first element of geminates.Footnote 14

The third position is the intervocalic position. Weakness in this position is manifest in it being a target of Lenition. These three positions in Campidanese conform with the observations made by Ségéral & Scheer (Reference Ségéral, Scheer, Carvalho, Scheer and Ségéral2008b: 135) that there are two ways of being weak – pervasive generalisations which should be reflected in theory. Looking at synchronic patterns in Campidanese, we can establish three positional effects:

-

1. Strong: The coda mirror, host to the entire consonantal inventory, and where Lenition is inert

-

2. Weak: Coda, where licensing power is severely restricted

-

3. Weak: Intervocalic, the target of Lenition

The different effects correspond to the intuition that weakness is a manifestation of loss or erosion of melodic material, while strength is resistance to such processes. The three effects also require a theory of prosodic structure sensitive to each position. A hierarchical syllable with an onset and coda can distinguish between strong onsets and weak codas, but it cannot isolate the intervocalic position, which is typically viewed as an onset despite its distinct phonological behaviour that contrasts with onsets in the strong position. A further desideratum of the theory is to explain geminate inalterability – rather than stipulating in the grammar that geminates are immune to Lenition, geminate inalterability should fall out naturally from basic principles of the formal system.

4.2.1. The analytic tool: Strict CV phonology

In order to capture the three distinct prosodic positions, this analysis makes use of the basic machinery of Strict CV phonology (Lowenstamm Reference Lowenstamm, Durand and Laks1996; Scheer Reference Scheer2004b, Reference Scheer2012), a development of the Government Phonology program (Charette Reference Charette1990; Harris Reference Harris1990; Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud1990; Harris & Kaye Reference Harris and Kaye1990). In Strict CV phonology, prosodic structure is built not out of hierarchical arborescent structures, but out of lateral relationships between constituents on a CV tier. This means that the three different positions of strength and weakness are distinguished by the different configurations of lateral relations between members of the CV tier.Footnote 15

In Strict CV, the skeletal tier is built from an invariant alternation between C and V positions.Footnote 16 Relations between C and V positions are defined by two lateral forces, government and licensing, and the difference between C and V lies in their distinct licensing powers. Co-occurrence restrictions between adjacent segments are not due to hierarchical syllabic structure, but to lateral relations between the segments; ‘branching onsets’ or ‘onset and coda’, for example, are not in a relationship derived from an arboreal hierarchy, but one derived strictly in terms of the lateral relationships between them (Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud1990). Syllabic structure, then, is not a phonological primitive per se, but a derived property of adjacency relations.

Roughly speaking, government is a force which serves to weaken or inhibit melodic material, while licensing reinforces it. Both originate at the right edges of words, propagating back – V positions with melodic material may govern and license constituents to their left. There is a hierarchical relationship between governing and licensing: they cannot both exert influence on the same segment (Scheer Reference Scheer2012). If a segment is potentially subject to both lateral forces, it will be subject to government. In turn, licensing will influence the next available segment. When a CV unit is full of melodic material, the V position will contract a relationship of licensing from any following licenser, while the C position will contract one of government.

In Strict CV, all morphological boundary information – information that communicates with the interfaces and is translated from morphology – must be in the form of CV units, meaning that representations contain an empty initial CV at the left edge of words. The difference between a CV unit and a conventional # is that a CV unit is a true phonological object through which morphology is translated into phonology, while # is an arbitrary diacritic whose only function is to mark morpho-syntactic boundaries. This initial CV may enter into a lawful lateral relationship just like any other CV position (Lahrouchi Reference Lahrouchi2018; Lowenstamm Reference Lowenstamm, Rennison and Kühnhammer1999; Scheer Reference Scheer2009, Reference Scheer2012). As a phonological object, it exerts an influence on the structure of lateral relationships in phonology.

The nature of the strict ordering of CV elements in lateral phonology, along with CV-interpreted morphosyntactic information, means that there is potential in any representation for a number of empty C or V positions – positions with no associated melody. Empty V positions are known as empty nuclei. All languages impose restrictions on the number of empty nuclei in a given prosodic representation. In order to remain unexpressed, empty nuclei must contract a relationship of government, which they get from any filled V position that follows. Consider the representation in (16), which shows the interaction between the forces of government, licensing and the empty positions in the initial CV:Footnote 17

In (16), C

![]() $_2$

contains lexically specified melodic material, and contracts a relationship of government from the following vowel, V

$_2$

contains lexically specified melodic material, and contracts a relationship of government from the following vowel, V

![]() $_2$

, which in turn licenses V

$_2$

, which in turn licenses V

![]() $_1$

, since the latter also contains lexically specified melodic material. V

$_1$

, since the latter also contains lexically specified melodic material. V

![]() $_1$

, on the other hand, must govern the empty V position of the initial CV, and thus licenses C

$_1$

, on the other hand, must govern the empty V position of the initial CV, and thus licenses C

![]() $_1$

. This means that C

$_1$

. This means that C

![]() $_1$

is in the position of the coda mirror; being [+Lic], it is not subject to lenition. Thus, [+Lic] is a formal configuration of prosodic structure that reinforces and does not diminish melodic primes; in Campidanese, this lateral configuration is phonologically stable. The position of the intervocalic C

$_1$

is in the position of the coda mirror; being [+Lic], it is not subject to lenition. Thus, [+Lic] is a formal configuration of prosodic structure that reinforces and does not diminish melodic primes; in Campidanese, this lateral configuration is phonologically stable. The position of the intervocalic C

![]() $_2$

is an onset, like C

$_2$

is an onset, like C

![]() $_1$

, but has a distinct status in this representation, since it is governed, but not licensed. This position, [+Gov], is where Lenition occurs – here /k/ is realised as [

$_1$

, but has a distinct status in this representation, since it is governed, but not licensed. This position, [+Gov], is where Lenition occurs – here /k/ is realised as [![]() ].

].

Since filled V positions license and govern, and codas are followed by empty V positions, they do not enter into any lateral relationship. The result is a [

![]() $-$

Lic,

$-$

Lic,

![]() $-$

Gov] position, with reducing power to license melodic primes. This weak position is subject to severe cooccurrence restrictions, with only /r/, homorganic nasals, or the first part of a geminate being allowed to surface as a coda in Campidanese. For example, a word such as /fatat/ ‘do-3sg’ has the following underlying representation:

$-$

Gov] position, with reducing power to license melodic primes. This weak position is subject to severe cooccurrence restrictions, with only /r/, homorganic nasals, or the first part of a geminate being allowed to surface as a coda in Campidanese. For example, a word such as /fatat/ ‘do-3sg’ has the following underlying representation:

The representation in (17) has an empty final V position. If an empty nucleus cannot contract a lateral relationship, it must be expressed.Footnote 18 In Campidanese, this restriction results either in the deletion of the coda or in the realisation of a paragogic copy vowel identical to the stem-final vowel in ungoverned empty V positions. The representation in (18) is the surface realisation of (17):

Lateral relations thus not only affect phonological computation, but also determine the well-formedness of a string (Scheer Reference Scheer2012: 145). In order to remain unexpressed, a V

![]() $_1$

must be governed by a following V

$_1$

must be governed by a following V

![]() $_2$

; if V

$_2$

; if V

![]() $_2$

is empty, it cannot govern V

$_2$

is empty, it cannot govern V

![]() $_1$

. This predicts that there may not be a sequence of two consecutive empty nuclei: an empty V

$_1$

. This predicts that there may not be a sequence of two consecutive empty nuclei: an empty V

![]() $_2$

cannot govern a preceding V

$_2$

cannot govern a preceding V

![]() $_1$

, which thus cannot remain empty and must be phonetically expressed. In classical terms, the result is epenthesis, as when the post-consonantal copy vowel surfaces in Campidenese. In this way, well-formedness does not come from outside of phonology in the form of arbitrary constraints – rather, it is the result of lateral relations (see Lai Reference Lai and Russo2015a,Reference Laib for a discussion of other similar effects elsewhere in Sardinian).

$_1$

, which thus cannot remain empty and must be phonetically expressed. In classical terms, the result is epenthesis, as when the post-consonantal copy vowel surfaces in Campidenese. In this way, well-formedness does not come from outside of phonology in the form of arbitrary constraints – rather, it is the result of lateral relations (see Lai Reference Lai and Russo2015a,Reference Laib for a discussion of other similar effects elsewhere in Sardinian).

The second solution for the problem presented by /fatat/ is to delete the final consonant. This solution is available when there is a following C-initial word, since final and internal codas do not have the same status in Campidanese. The latter precede a governed nucleus, which thus cannot be expressed and so cannot contract any kind of lateral relationship with any final consonant. The association between this consonant and its position on the CV tier then moves to the following consonant, resulting in compensatory lengthening (represented by the dashed association line), as in /fatat luna/ ‘the moon is shining’, represented in (19):

In (19), government and licensing proceed as normal from the right edge. The /l/ in C

![]() $_4$

is normally subject to Lenition, but is protected here because it is licensed. The empty position at V

$_4$

is normally subject to Lenition, but is protected here because it is licensed. The empty position at V

![]() $_3$

attracts government from V

$_3$

attracts government from V

![]() $_4$

, remaining empty, and consequently C

$_4$

, remaining empty, and consequently C

![]() $_3$

is a coda position, a position which imposes severe distributional restrictions on segmental material in Campidanese, as mentioned above. Since the stop in C

$_3$

is a coda position, a position which imposes severe distributional restrictions on segmental material in Campidanese, as mentioned above. Since the stop in C

![]() $_3$

cannot be associated with the timing tier, the association it projects moves to C

$_3$

cannot be associated with the timing tier, the association it projects moves to C

![]() $_4$

, resulting in geminate structure. V

$_4$

, resulting in geminate structure. V

![]() $_2$

contracts lateral relationships as normal, and V

$_2$

contracts lateral relationships as normal, and V

![]() $_1$

governs the V position in the initial CV instead of C

$_1$

governs the V position in the initial CV instead of C

![]() $_1$

, resulting in another strong position.

$_1$

, resulting in another strong position.

What is the content of this restriction on coda licensing? Harris (Reference Harris1990) and Cyran (Reference Cyran, Carvalho, Scheer and Ségéral2008, Reference Cyran2010) argue that the amount of melodic material in a segment corresponds to its substantive complexity: the more melodic material in a segment, the more complex it is. Cyran (Reference Cyran2010) argues that substantive complexity has consequences for prosodic structure, since the more melodic material a segment has, the more licensing strength it requires. Such complexity scales mean that positions that are not licensed cannot host as much melodic material as those that are. In Campidanese, positions that contract no lateral relationships – codas – are weak, licensing only minimally complex segments. In particular, codas may license nasal segments homorganic for place and the first parts of geminates, structures that have in common the ‘sharing’ of melodic material with following segments. In these cases, the strength of the structures is reflected by the sharing of segmental material that would otherwise be prohibited in [

![]() $-$

Lic,

$-$

Lic,

![]() $-$

Gov] positions (Honeybone Reference Honeybone, Carr, Durand and Ewen2005b).

$-$

Gov] positions (Honeybone Reference Honeybone, Carr, Durand and Ewen2005b).

In sum, lateral relations define the three positions of prosodic strength, with each receiving a unique prosodic identity. Importantly, they define the coda mirror as [+Lic], making it formally distinct from the intervocalic position, which is [+Gov]. Finally, since codas do not contract any lateral relationships, being [

![]() $-$

Lic,

$-$

Lic,

![]() $-$

Gov], their power to license contrasts is reduced. The three positions are summarised in Table 4.

$-$

Gov], their power to license contrasts is reduced. The three positions are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4 The lateral relations of the three positions of strength in Campidanese.

Distinguishing among these three positions means that the context of Lenition in Campidanese can be given a unified context: [+Gov]. Only segments with this lateral configuration can be targeted by Lenition; any other configuration is spared from its effects.

4.2.2. Prosodic position and geminate inalterability

We are now in a position to see how prosodic position interacts with Lenition and Fortition and gives rise to geminate inalterability – and how the notions of strength and weakness may be understood in a substance-free approach.

First, let us consider the case of Lenition, which targets intervocalic obstruents, as in (20):Footnote 19

In (20), V

![]() $_3$

licenses V

$_3$

licenses V

![]() $_2$

, which in turn licenses V

$_2$

, which in turn licenses V

![]() $_1$

, resulting in both C

$_1$

, resulting in both C

![]() $_3$

and C

$_3$

and C

![]() $_2$

being [+Gov] – weak positions. Since those positions are filled by segments subject to Lenition, each is realised on the surface as its corresponding weak allophone.

$_2$

being [+Gov] – weak positions. Since those positions are filled by segments subject to Lenition, each is realised on the surface as its corresponding weak allophone.

One prediction made by this theory is that word-medial intervocalic positions, such as C

![]() $_3$

, are also [+Gov], and thus potential targets for Lenition. While I presented conceptual arguments for considering spirants in this position to be the result of lenition in §3.2.1, to those arguments can now be added a theoretical one: this position is weak by virtue of its prosodic structure, so any potential target in this position is expected to be subject to Lenition. This is exactly how a learner is able to recover singletons in this position, since any surface stop in a word-medial position is a geminate, any surface spirant is a singleton.Footnote

20

Thus, the simplifications to the grammar that come from assuming Lenition is active in this position fall out from the lateral relations of intervocalic consonants.

$_3$

, are also [+Gov], and thus potential targets for Lenition. While I presented conceptual arguments for considering spirants in this position to be the result of lenition in §3.2.1, to those arguments can now be added a theoretical one: this position is weak by virtue of its prosodic structure, so any potential target in this position is expected to be subject to Lenition. This is exactly how a learner is able to recover singletons in this position, since any surface stop in a word-medial position is a geminate, any surface spirant is a singleton.Footnote

20

Thus, the simplifications to the grammar that come from assuming Lenition is active in this position fall out from the lateral relations of intervocalic consonants.

In Strict CV, the relationship which characterises obstruent–sonorant (TR) clusters is known as infrasegmental government (see Scheer Reference Scheer2004b, Reference Scheer2012). Infrasegmental government (represented as T

![]() $<$

=R) is a specific kind of government which holds between constituents of branching onsets, and has the effect of suppressing exponence of the V position between the two members, which remains empty. In contrast to other empty V positions, the empty V positions in TR clusters are good lateral actors, and may contract government and licensing relationships with other CV positions.

$<$

=R) is a specific kind of government which holds between constituents of branching onsets, and has the effect of suppressing exponence of the V position between the two members, which remains empty. In contrast to other empty V positions, the empty V positions in TR clusters are good lateral actors, and may contract government and licensing relationships with other CV positions.

In (21), we see that V

![]() $_2$

is circumscribed by infrasegmental government and thus is a good lateral actor, governing C

$_2$

is circumscribed by infrasegmental government and thus is a good lateral actor, governing C

![]() $_2$

and triggering lenition at that position:

$_2$

and triggering lenition at that position:

This brings us back to geminate inalterability. As argued in §3.2.4, in Campidanese, phonetic duration is not a consistent correlate of phonological geminates – rather, it is resistance to Lenition that is the defining characteristic of phonological geminates. Infrasegmental government means that the empty V position between two consonants in a tautosyllabic TR cluster does not act like an empty V position between heterosyllabic consonants. Strict CV predicts that any C position which is [+Gov] is weak, and since geminates are not a target of Lenition, they must have a different lateral configuration, corresponding to prosodic strength. In all geminates, there is an empty V position between two C positions. This empty V must be governed to remain empty, as we can see for lexical geminates, as in makku ‘crazy’ in (22):

In (22), V

![]() $_3$

governs the empty position V

$_3$

governs the empty position V

![]() $_2$

and licenses C

$_2$

and licenses C

![]() $_3$

, leaving C

$_3$

, leaving C

![]() $_3$

in the strong [+Lic] position and protecting it from Lenition. C

$_3$

in the strong [+Lic] position and protecting it from Lenition. C

![]() $_2$

, in turn, contracts no lateral relationship, leaving it in the coda [

$_2$

, in turn, contracts no lateral relationship, leaving it in the coda [

![]() $-$

Lic,

$-$

Lic,

![]() $-$

Gov], which is also immune to lenition. Since in the case of (22) the coda is the first element of a geminate, the weak position C

$-$

Gov], which is also immune to lenition. Since in the case of (22) the coda is the first element of a geminate, the weak position C

![]() $_2$

is able to license the melodic material inherited from C

$_2$

is able to license the melodic material inherited from C

![]() $_3$

. This gives us a formal representation of strength inherent in lateral relations: their interaction with multiply associated segments determines where Lenition is active and where it is not.

$_3$

. This gives us a formal representation of strength inherent in lateral relations: their interaction with multiply associated segments determines where Lenition is active and where it is not.

4.3. Melodic representations

Before coming to an examination of the computational wing of Campidanese, I will introduce a system of formal representations and their organisation in the consonantal system. I do not address the vocalic system because its representational content is not relevant to Lenition or Fortition, but a full account of Campidanese phonology would require such an analysis. The principal ambition of this section is to show how Lenition modifies melodic structure.

Table 5 is a phonological schema of the phonemic consonants in Campidanese. A few precisions are in order. The segments /dz/, /v/ and /ɲ/ are exceedingly rare, and found only in recent loanwords from Italian (Lai Reference Lai, Gabriel, Gess and Meisenburg2021b). The retroflex /ɖ/ is only ever encountered as a geminate, and with the exception of the object proclitics [ɖ:a(s)], [ɖ:u(s)], [ɖ:is], it is only found word-medially. All other consonants in Table 5 are phonemic word-initially.

Table 5 The consonantal segments of Campidanese Sardinian.

The organisation of Table 5 deserves some discussion. In substance-free theories, melodic representations do not contain phonetic information. They are abstract, purely symbolic counters which index natural class-hood and mark contrast. That is, labels such as [dental] or [nasal] are not claims about the substantive content of features; they are merely useful shorthand used by linguists to refer to contrastive features or to natural classes (see Chabot Reference Chabot2022 for discussion). The organisation of Table 5 is not substantive, but phonological. For example, the position of the coronal stops /t d ʦ dz/ shows each pair at distinct places of articulation. This follows from a principle that views affricates as phonological singletons – simple stops with no continuant element or friction (Clements Reference Clements, Fujimura, Joseph and Bohumil1999; Scheer Reference Scheer and Ploch2003). Affricates rarely have a corresponding plosive at the same place of articulation, while they frequently share a place of articulation with fricatives (Berns Reference Berns2008: 102). Though the articulatory configuration of affricates is much like that of fricatives, phonologically they pattern with stops (LaCharité Reference LaCharité1993; Berns Reference Berns2008). Kehrein (Reference Kehrein2002: 5) is explicit on this point, arguing that nothing in their underlying representations allows for stops to be distinguished from affricates, which he terms the Generalised Stop Approach. Indeed, in Campidanese, when /ʧ/ geminates, it is the stop portion which becomes long, as in [fratʧi] ‘sickle’ and [krutʦu] ‘short’.

The place distribution of affricates is dependent on the distribution of stops, and affricates and stops are in complementary distribution with respect to place of articulation – what LaCharité (Reference LaCharité1993: 75ff) refers to as the stop–affricate dependency. Where stops and affricates occur at the same place of articulation, and where they are contrastive, there must be a feature distinguishing the class of stops from the class of affricates. Thus, for LaCharité (Reference LaCharité1993), Clements (Reference Clements, Fujimura, Joseph and Bohumil1999) and Kehrein (Reference Kehrein2002), the difference between affricated and non-affricated stops is one of place. To distinguish between /t d/ on the one hand and /ʦ dz/ on the other, each pair is assigned a distinct phonological place of articulation.

An additional comment can be made on the distribution of stops, fricatives and liquids, especially where each category contains a voiced and voiceless member. There is a voluminous literature on how voicing contrasts are represented in phonology and implemented phonetically (Halle & Stevens Reference Halle and Stevens1971; Keating Reference Keating1984; Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson and Salmons1995, Reference Iverson and Salmons2006, Reference Iverson, Salmons, Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011; Lombardi Reference Lombardi1995; Avery & Idsardi Reference Avery, Idsardi and Hall2001; Honeybone Reference Honeybone, Oostendorp and Weijer2005a; Cyran Reference Cyran2014). What is important here is that, with the exception of /ʦ/ – which is always a geminate – each place of articulation has a leniting member (on the left) and a non-leniting member (on the right). Each segment on the left in Table 5 is a member of the exact class targeted by Lenition. However, the category targeted by Lenition cannot be voiceless segments, since it includes /l/. I suggest that the distinction between voiceless and voiced obstruents in Campidanese can be profitably conceived as being one of fortis and lenis (see also Bolognesi Reference Bolognesi1998: 163, Lai Reference Lai2021a: 82ff., Virdis Reference Virdis1978: 91).

Here, applied to Campidanese, fortis and lenis are labels of convenience, based on the observation that the articulation of /p t ʧ k f s l/ is stable throughout the process of Fortition, while that of /b d ʤ g/ is not, resulting in spirants. Conversely, /p t ʧ k f s l/ are realised with phonetic voicing after Lenition, a property of lenis articulations. The contrast between fortis and lenis in Campidanese is not expressed phonetically the way it is in Germanic, but as true voicing, as is typical in Romance (cf. Cyran Reference Cyran2014 for Polish, Iosad Reference Iosad2012 for Friulian and Iosad Reference Iosad2017 for Bothoa Breton, where it is argued that the relationship between phonetic voicing and phonological voicing is arbitrary).

In Campidanese, lenis is realised with active closure voicing, and fortis segments are not realised with aspiration (Keating Reference Keating1984). Consequently, the target of Lenition is the set of fortis segments, /p t ʧ k f s l/, which are marked by a substance-free feature, [fortis]. Those segments which are not marked by [fortis] do not undergo Lenition. The same is true of those segments such as /ɖ/ and /ʃ/ which are always represented as lexical geminates (see Lai Reference Lai2015b for discussion).

5. Phonological computation in Campidanese Sardinian

5.1. Two computational domains and an interface

I have identified two phonological processes in Campidanese, which I have referred to as Fortition and Lenition. This section will provide an analysis of how these two computational processes operate. It shows that Fortition operates at the prosodic level, associating melodic material with additional timing positions, while Lenition operates on the melodic tier, active in a particular prosodic context, [+Gov], and resulting in the loss of melodic material.

Some form of an interface between phonology and the phonetic module is a necessary property of any substance-free theory of phonology (see Scobbie Reference Scobbie, Ramchand and Reiss2007; Boersma & Hamann Reference Boersma and Hamann2008; Hamann Reference Hamann, Kula, Botma and Nasukawa2011; Scheer Reference Scheer, Cyran and Szpyra-Kozłowska2014; Kingston Reference Kingston, Katz and Assmann2019 for proposals of interface models). A one-to-one mapping between phonological features and phonetic exponence cannot always be assumed (Keating Reference Keating and Newmeyer1988), as phonological features and phonetic properties do not map back to each other invariably (see, e.g., Hamann Reference Hamann2004 for retroflexivity, Kingston & Diehl Reference Kingston and Diehl1994 and Honeybone Reference Honeybone, Oostendorp and Weijer2005a for voicing and Clements Reference Clements, Kingston and Beckman1990 for sonority). Phonetic realisations of phonological objects are not only learned, but they may vary in unexpected and unpredictable ways (Chabot Reference Chabot2019).

In the model I use here, post-phonological spell-out, the mapping between phonetic realisations and phonological objects is a look-up function (Scheer Reference Scheer, Cyran and Szpyra-Kozłowska2014). Spell-out is a lexicon of instructions that map from underlying forms to surface forms. As such, it works like a dictionary, and each entry must be learned during acquisition; as is true for morphosyntax, mappings are not innate. While phonological computation works over phonological features, it is in spell-out that features are imbued with phonetic substance. Spell-out functions once all phonological computation has been carried out; it is purely translational and performs no computation itself. Thus, it cannot, for example, insert or remove features or change association lines or prosodic structure. I will show how this arbitrary spell-out produces spirant outputs of voiced stops that undergo Fortition in the following section.

5.2. A formal account of Fortition

First, let us examine Fortition through the lens of the prosodic structures established in §4.2. In §3.2.5, it was shown that the loss of a final consonant preceding a voiceless consonant triggers a process of compensatory lengthening by which the voiceless consonant is both exempt from Lenition and realised with phonetic duration, as in pappat pani ‘eat-3sg bread’ in (23):

In (23), C

![]() $_4$

is [

$_4$

is [

![]() $-$

Lic,

$-$

Lic,

![]() $-$

Gov], and thus subject to strict licensing requirements. Since /t/ does not meet those requirements in Campidanese, it is not associated with the prosodic position, and cannot surface. However, the melodic material associated with C

$-$

Gov], and thus subject to strict licensing requirements. Since /t/ does not meet those requirements in Campidanese, it is not associated with the prosodic position, and cannot surface. However, the melodic material associated with C

![]() $_5$

is [+Lic], and associated with C

$_5$

is [+Lic], and associated with C

![]() $_4$

by Fortition, marked with a dashed line. The difference between postlexical geminates and lexical geminates is inherent in the structure in

$_4$

by Fortition, marked with a dashed line. The difference between postlexical geminates and lexical geminates is inherent in the structure in

![]() $\text {C}_{4}\text {C}_{5}$

, which represents double association derived through Fortition, and

$\text {C}_{4}\text {C}_{5}$

, which represents double association derived through Fortition, and

![]() $\text {C}_{2}\text {C}_{3}$

, in which the double association is part of the lexical representation.

$\text {C}_{2}\text {C}_{3}$

, in which the double association is part of the lexical representation.

This brings us to the second kind of Fortition discussed in §3.2.5, that of RF. On the surface, the positional description of RF is intervocalic, yet Lenition is never triggered. Recall that in RF a closed class of lexical objects triggers gemination of a following consonant. Lexical objects in this set contain an empty CV in their underlying representations (Chierchia Reference Chierchia1986; Larsen Reference Larsen and Sauzet1998; Passino Reference Passino2013). In this way, they are representationally distinguished from non–RF-triggering lexical objects, as shown in (24):