Introduction

The care of a patient commences with the first consultation and often continues into a lifelong therapeutic bond despite cure or disease progression. Reference Trevino, Maciejewski and Epstein1 Clinical examination is an essential component of disease evaluation, assessing clinical response and toxicity and complements imaging findings. Reference Rosenzweig, Gardner and Griffith2 Minimisation of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection risks necessitated cancellation or rescheduling of elective outpatient follow-ups. Moreover, redeployment of oncology staff to COVID-19 workflow has also contributed towards curtailment of cancer care. Reference Al-Shamsi, Alhazzani and Alhuraiji3 Although the pandemic demands attention, it cannot undermine the importance of the initial examination, patient communication, treatment review and follow-ups in a cancer care setting. The excessive focus on COVID-19, leading to a diminished quality of cancer management and suboptimal cancer outcomes, is not desirable. Minimising interruptions to cancer treatment while safeguarding the well-being of patients and healthcare providers is paramount. With regard to radiation oncology, the RADS framework: Remote visits, and Avoidance, Deferment or Shortening of radiation therapy, initially proposed for prostate cancer, serves as a useful template to build upon for all disease sites. Reference Zaorsky, Yu and McBride4

Importance of follow-up and novel adaptations

Surveillance following treatment for cancer aids in identifying early recurrence or a new primary, monitoring toxicity and addressing patient symptoms. Reference Vargas, Sheffield and Parmar5 It serves to monitor overall disease outcomes for a region and the quality of oncology services. Reference Swaminathan, Rama and Shanta6 Patients prefer regular follow-up with tests and have found them to be reassuring. Despite the robust ethos, proof of the concept of routine surveillance in the era of evidence-based medicine is weak. Reference Shah and Denlinger7 The worth of regular clinical follow-ups in all treated patients has been questioned for decades, especially in low middle-income countries (LMIC). In countries like India, with a large population, rising cancer incidence, inadequate infrastructure and poor doctor–patient ratio, maintaining regular follow-ups are a challenge. The meta-analysis by Jeffery et al. showed that there was no survival benefit with the intensification of follow-up in colorectal cancers following curative surgery, despite better salvage rates. Reference Jeffery, Hickey and Hider8 The alternative options to a face-to-face clinical follow-up include telephonic structured interviews or questionnaires, personal digital assistant capture systems, follow-up with primary care physicians or general practitioners and follow-up by an allied healthcare professional. Reference Schütze, Chin and Weller9,Reference Cox and Wilson10 The use of these strategies have proven to be non-inferior in breast, prostate, lung and early endometrial cancers. Reference Dickinson, Hall and Sinclair11,Reference Mathew, Agarwal and Munshi12 Faithful et al. have reported the safety and feasibility of telephonic follow-up in patients undergoing radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Reference Faithfull, Corner and Meyer13 Innovative approaches, like the use of WhatsApp messenger services have also been tried during this pandemic. Reference Gebbia, Piazza and Valerio14 Trials with family physician led follow-up have involved early-stage patients, indolent tumour diagnosis, and many have addressed the psychological issues rather than clinical outcomes. Reference Dickinson, Hall and Sinclair11–Reference Faithfull, Corner and Meyer13

Hurdles for cancer care follow-up in LMIC

Robust follow-up depends on accessibility, ease, patient understanding of the need for periodic assessments, trust and economic viability. The various challenges for follow-up are poor patient compliance due to financial constraints resulting from out-of-pocket spending, large rural populations having to travel long distances to access the cancer centre and busy outpatient clinics with few clinicians adding to the waiting time. High rates of illiteracy and lack of access to technology (smartphone, computers, internet access) curtails telemedicine consultations. The COVID-19 pandemic has reduced health seeking behaviour, leading to late clinical presentation and increased distress among patients. Reference Maringe, Spicer and Morris15,Reference Ballal, Gulia and Gulia16 Early detection of residual or recurrent disease is missed due to reduced follow-up visits.

Modification of follow-up visits

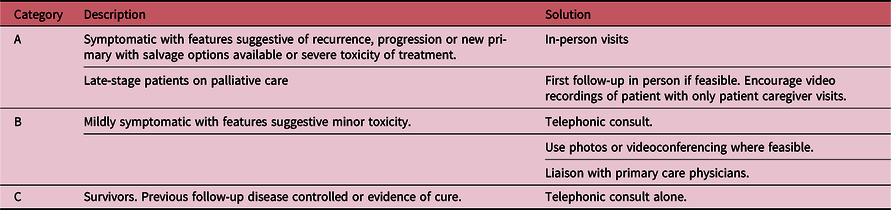

Delaying or postponing all follow-up visits until the end of pandemic may lead to missing recurrences, late presentation of disease and risk of overburdening the system with the accumulation of visits. This is amplified in LMIC with lack of well-defined screening programmes and the collapse of primary healthcare by COVID-19. These are likely to impact survival and quality of life. In our opinion, telephonic follow-up assumes a middle path between no follow-up and physical follow-up. It offers the benefits of ease of access and reduced cost leading to increased compliance, while providing reassurance, guidance and timely intervention, in addition to the valuable capability of tracking the patient’s status. Virtual visits with detailed history assisted with photographs or videoconferencing may enable the clinician to get a better picture. A study from India has shown video follow-up to be feasible in neuro-oncology practice. Reference Patil, Pande and Chandrasekharan17 A telephonic consult would serve as a triage to decide on the need for examination and imaging tailored to patients’ expectations and fears. Table 1 shows prioritisation of follow-up visits.

Table 1. Categories for prioritisation of follow-up

A simple telephone access is feasible for all. While during the pandemic, patients have welcomed this move, it could have psychosocial consequences for a few instilling a sense of abandonment while struggling with diagnosis and treatment. With increasing adoption, we can expect further refinements in the teleconsultation process over time. These include videoconferencing, development of a local directory of primary care physicians with access to Information Technology for sharing information and training nurses or dedicated clinical managers to conduct telephonic follow-ups. This strategy needs to be validated both within the hospital and out in the community and be developed so that it is sustainable throughout the present pandemic and unexpected events in future.

We should continue to have in-person follow-ups and examination based on risk assessment and telephonic triage. In the words of William Osler “Medicine is learned by the bedside and not in the classroom. See and then reason and compare and control. But see first”. Reference Stone18 In the long run, no technology can substitute a doctor’s clinical acumen based on examination. Slow resumption of follow-up examinations should be considered with precautions in place.

Conclusion

Telephonic consultation could facilitate triaging of ambulatory cancer patients and enable allocation of face-to-face consultations for high priority patients.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.