Australia is one of few countries in the world that actively manages artifacts in public possession that were removed from shipwreck sites prior to their declaration as protected. It is also one of few countries in the world to have conducted a national amnesty (an event approved by government offering immunity from prosecution) for underwater cultural heritage (UCH) artifacts recovered by the public prior to their declaration of protection, along with the “Wreck Amnesty in the United Kingdom in 2001, and the Wreck Amnesty in the British Overseas Territory of Bermuda in the North Atlantic Ocean in 2003” (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2009a:99).

The effective administration of legally protected UCH artifacts (also known legally as relics from 1976 to 2019 and articles from July 1, 2019, to the present) in Australia remains an ongoing process of development and refinement to achieve improvements in collection and conservation management outcomes for the artifacts in public possession, national consistency of management decision-making, and record keeping, while reducing the regulatory burden on the public and the Commonwealth, state, and Northern Territory governments, which administer the Australian Underwater Cultural Heritage Program (AUCHP; previously known as the Historic Shipwrecks Program [HSP] from 1976 to 2018). This article outlines, chronologically, the development of the legislative, policy, and administrative practices that have been used to protect shipwrecks and other UCH artifacts in Australia at the Commonwealth (also known as the Australian Government or Federal Government) level, stemming from the introduction of legislation in 1976 with a retrospective protection extending to sites that had been significantly looted prior to its introduction.

Four key themes are presented and assessed throughout the article: ownership/possession of protected relics/artifacts, permitting, management/compliance, and information management. Although museums regularly manage large artifact collections, it is less common for government-based site heritage management agencies in Australia to do so, particularly to endeavor to manage collections in the possession, custody, and control of private individuals. Indeed, it is the anomalous nature of the legislative responsibility that offers the key learning outcomes to readers, should they ever be placed in the position of having to plan and conduct an archaeological amnesty in their country and subsequently to manage the results of that amnesty.

THE POLICY BASIS FOR PROTECTION OF AUSTRALIA'S SHIPWRECKS AND ASSOCIATED ARTIFACTS

Post–World War II Australians embraced the recently invented Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus (SCUBA) as a recreational hobby. Diving around the coastline led to the inevitable discovery of some of our shipwreck heritage. In 1963, the discovery of Vergulde Draeck (1656) and Batavia (1629), old Dutch wrecks located off the coast of Western Australia (WA), led to both a frenzy of looting and a regulatory response to protect that shipwreck heritage (Henderson Reference Henderson1986).

In 1964, the WA Government introduced the first UCH legislation both in Australia and in the world when it amended the Museum Act 1959 to protect historic wrecks and their associated artifacts found off the coast of WA (Henderson Reference Henderson1986; Kennedy Reference Kennedy, Green, Stanbury and Gaastra1998; Museum Act 1964). The management of artifacts associated with protected shipwreck sites has been a facet of Australian UCH management since that date.

In 1972, the Government of the Netherlands, as successor of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC, Dutch East India Company), transferred the right, title, and interest to VOC wrecked vessels lying off the coast of WA to the Commonwealth of Australia. By this date, four VOC shipwrecks had been discovered: Batavia, Vergulde Draeck, Zuytdorp (1712), and Zeewijk (1727).

In 1973, the WA Government enacted the Maritime Archaeology Act 1973 (WA), Australia's first stand-alone legislation to protect shipwrecks. The Maritime Archaeology Act claimed jurisdictional control of waters beyond three nautical miles (nm), but this claim was overturned several months later with the introduction of the Commonwealth Seas and Submerged Lands Act 1973 (Brazil Reference Brazil2001; O'Keefe and Prott Reference O'Keefe and Prott1978), eventually limiting state control out to 3 nm. This jurisdiction change enabled a successful challenge in the High Court of Australia to the WA Government's Maritime Archaeology Act by Alan Robinson, one of the reported finders of Vergulde Draeck in 1963 and subsequently one of Australia's most well-known shipwreck looters (Kennedy Reference Kennedy, Green, Stanbury and Gaastra1998; Ryan Reference Ryan1977). Recognizing the inevitable success of Robinson's legal challenge to the Maritime Archaeology Act's claimed jurisdiction—and to counter treasure hunting and protect the old Dutch shipwrecks now belonging to Australia as well as other shipwrecks—the Commonwealth passed into law the Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976 (the Shipwrecks Act; Viduka Reference Viduka2014). Schedule 1 of the Shipwrecks Act was the “Agreement between Australia and the Netherlands Concerning Old Dutch Shipwrecks” (ANCODS; 1972). As with the WA Museum Act 1964 amendment, the Shipwrecks Act also extended protection of declared sites to protect all the associated artifacts. In the Shipwrecks Act, this protection was retrospective, encompassing any previously recovered relics (the legal term used to describe all objects/artifacts that are cargo, part of the ship, personal possessions, or human remains), as well as all those in situ, and it included provisions to enable the management of relics.

THE HISTORIC SHIPWRECKS ACT 1976: SITES AND ASSOCIATED RELICS

The Shipwrecks Act jurisdictional waters extended from the Lowest Astronomical Tide (LAT) mark along the coastline out to the edge of the continental shelf or Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), or whichever is farther. The Shipwrecks Act established that historic shipwrecks and their associated relics were of value to all Australians and incorporated the principles from the ANCODS agreement of “being available to the public and the scholar” (Ryan Reference Ryan1977:24). Although protection was initially by individual declaration, in 1985 the Shipwrecks Act was amended to include a section (s.) 4a provision so that all shipwrecks 75 years or older could be protected automatically (Cassidy Reference Cassidy1991). However, the s.4a provision was only enacted on April 1, 1993, and this was followed by an amnesty period (which will be discussed in more detail below).

THE HISTORIC SHIPWRECKS PROGRAM: NATIONAL COLLABORATIVE ADMINISTRATION

The Shipwrecks Act was drafted with the concept of collaborative delivery between the Australian Government and the states, the Northern Territory, and Norfolk Island (the jurisdictions) as the integral methodology for undertaking day-to-day management outcomes (Ryan Reference Ryan1977). The Australian Government minister responsible for the Shipwrecks Act could delegate certain day-to-day administrative powers, which included powers to assist in the administration of protected relics through their notification and permitting. The senior heritage official in each jurisdiction responsible for similar shipwreck legislation was delegated by the Australian Government minister. Known as the “Delegates,” which included a Commonwealth Delegate, they were usually supported by a senior maritime archaeologist in the jurisdiction, who was called the “Practitioner.” This facilitated a national collaborative approach to the management of Australia's shipwrecks and associated relics (artifacts), which was coordinated and led by the Australian Government through the HSP, with the jurisdictions undertaking day-to-day site and relic notification and permitting activities, site inspections, and data input into the minister's register of historic shipwrecks (Viduka Reference Viduka2012).

The HSP was listed in the budget portfolio statement for a short period. However, since around 2000, funding has solely been subject to allocation from within the relevant departmental budget. At no time has the HSP or its antecedent program used fines from noncompliance to help fund the program, although a provision for cost recovery from the public was included in the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (more detail below), in line with broader Australian Government legislative drafting policy.

OWNERSHIP/POSSESSION OF PROTECTED RELICS/ARTIFACTS

The Navigation Act

The issue of who legally owns relics from protected shipwreck sites in Australia is a mix of evolving law and international agreement and is a key consideration to underpin management.

It is important to note that the idea of “finders keepers” has never operated in Australia regarding shipwrecks or sunken aircraft. Under the early British Merchant Shipping Acts and Australia's Navigation Act 2012 (Commonwealth; previously, the Navigation Act 1912), “wreck” is the property of the original owner or the “Crown,” which in this case is represented by the Commonwealth, if it is unclaimed after one year. Once a shipwreck under Commonwealth jurisdiction becomes heritage protected, the Navigation Act transfers responsibility for its management to the Shipwreck Act, but ownership remains with the Commonwealth.

Treaties and Agreements

Another source of ownership of shipwrecks and associated relics comes from treaties and agreements made with foreign governments. As mentioned above, and separate from the 1972 Agreement with the Netherlands, there are also other individual arrangements that transfer ownership of collected artifacts from United Kingdom sovereign vessels, such as HMS Sirius (1790), to Australia.

Recognition of Ownership “Rights” in the Australian Constitution

Separate from the issue of who legally owns UCH relics is the concept of property rights. The Australian Constitution contains a mechanism for protecting the property rights of the States, Northern Territory, and individual persons in the event of acquisition of property under a Commonwealth law. Clause 51(xxxi) allows the Commonwealth to make laws concerning the acquisition of property and requires it to provide fair compensation on “just terms.” To reflect the need to recognize the rights of individuals who had recovered relics from shipwreck sites prior to their retrospective declaration of protection, the Shipwrecks Act was the first Commonwealth legislation to include specific provisions to invoke Clause 51(xxxi), primarily in s.21 of the legislation.

Understanding Superior Legal Title

Many protected relics remain in the possession of individuals or private organizations. Although long-term possession of protected relics may create some proprietary interest that needs to be taken into consideration, generally the Commonwealth is the “owner” because it has the strongest legal title to shipwrecks and associated relics.

Unless a person can prove they have a superior legal title, the Commonwealth would not be required to pay compensation in a case where it removed the relic from a person's possession because it is not an acquisition of property, given that the Commonwealth is already the owner. This would also be the case if a person has not fulfilled their regulatory responsibilities under the legislation or if possession has been obtained through an illegal act.

The only other party with a more superior property title to a shipwreck and its artifacts would be the original owner or someone who purchased the rights to the shipwreck from the original owner, and where those rights are proved not to have been abandoned or extinguished over time. Regardless of the ownership status, the associated artifacts of a protected wreck site remain protected under the Shipwrecks Act and subject to its regulatory requirements.

PROTECTION AND MANAGEMENT OF RELICS IN THE SHIPWRECKS ACT

Communicating to the Public

With the introduction of the Shipwrecks Act in 1976, and again when the 1993 Amnesty was announced (see below), it was vital to communicate to the Australian public what a person's legislative responsibilities and obligations were and what penalties might be incurred by failing to comply with these requirements (Australian Government Reference Government1993, Reference Government1996; Henderson Reference Henderson1994). Important messages to communicate to the public, particularly initially, were that

• Finders are not keepers

• Removing relics from sites diminished the site's archaeological potential and the ability to learn more from our past

• Relics recovered from a marine environment will deteriorate and will require conservation and collection care

• A relic in their possession did not actually belong to them, even if they had purchased it

Finders Are Not Keepers

Unsurprisingly, these messages were news to many. Early posters, flyers, and brochures emphasized that the Shipwrecks Act existed to protect declared shipwrecks and associated relics and aimed to stop people seeing wrecks as “sunken treasure.” Anyone who found the remains of a ship in Australian waters, or a relic associated with a ship, needed to notify the authorities as soon as possible and to give them information about what had been found and where. Individuals, companies, or other corporate bodies that failed to notify authorities risked fines ranging from $2,000 up to $10,000 AUD. Individuals may also have been required to provide information about the location of relics that they possessed in the past.

Regulation of the Transfer, Possession, and Custody of Protected Relics

Public communications also emphasized that it was and is illegal to disturb or remove items from historic shipwrecks, unless under permit. However, the law did provide ways for people who were in possession of protected relics prior to the site's declaration as protected to trade that item after they met their notification requirements. The regulation of the transfer, possession, and custody of relics—including coins—from historic shipwrecks was administratively burdensome under the Shipwrecks Act.

Notification

Anyone who bought or in any other way came into possession of material from a historic shipwreck was required to notify the minister within 30 days. In practice, notifications were usually made to the minister's Delegates in each jurisdiction through paper-based systems.

Permit

Although individuals, dealers, and collectors could legally purchase or sell notified protected relics from shipwrecks, it was necessary to obtain a permit before selling or otherwise disposing of the relic. At the time, significant fines could apply for persons failing to obtain a permit before selling relics. The penalty for sale or disposal without a permit was a $10,000 fine for an individual, or five years imprisonment, or both. A company or body corporate risked a fine of up to $50,000.

Similar penalties applied for removing relics from historic shipwrecks in Australian waters without a permit or damaging or destroying relics such as coins.

Other Obligations on Custodians

The Shipwrecks Act also imposed a requirement on people in the possession, custody, and control of protected relics to maintain the condition of the relic. The minister could seize an item for the purpose of a relic's conservation or display.

THE 1993 AMNESTY

Around the mid-1980s, Australian maritime archaeologists “knew that many shipwreck sites had been and were still being looted” (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2009a:94). Initially, the Shipwrecks Act used an individual declaration of protection model that simply did not translate to the effective protection and management of sites subject to looting in the marine environment, prompting a rethink. In 1985, the Australian Government amended the Shipwrecks Act, including a s.4a rolling-date, blanket protection provision that would automatically protect all shipwrecks and their associated relics that had been in jurisdictional waters for more than 75 years (Viduka Reference Viduka2015). This provision remained inactive until it came into force on April 1, 1993.

In conjunction with the introduction of the s.4a provision, on May 1, 1993, the Australian Government commenced a nationwide amnesty. The amnesty had multiple objectives, most important of which was the legal requirement to ensure that members of the public were not caught in retrospective noncompliance. From an archaeological perspective, the amnesty offered the opportunity for archaeologists to document missing information, before it was permanently lost, about protected relics recovered prior to a shipwreck's declared protection, and it encouraged the public to come forward with information about discovered sites and artifacts without penalty (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2009a, Reference Rodrigues2009b). The amnesty covered a period of 11 months and had two parts: initially, it ran to October 30, 1993, and it was later extended for another five months, finally ending on March 31, 1994. Figure 1 shows a contemporary amnesty flyer with the amnesty conclusion date modified.

Figure 1. Amnesty promotion flyer from 1993.

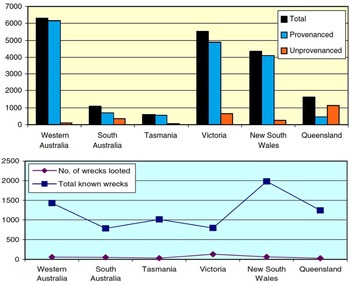

Members of the public were directed to declare their shipwreck relics to the state Delegates. The parameters of the amnesty required jurisdictions to record the custodian, what the relic was, what site it was from (if known), and where the object was located. Due to the location of the old Dutch shipwrecks off the coast of Western Australia and the large amount of material collected from these sites, the Western Australian Museum undertook the largest role of any jurisdiction in recording and photographing notified relics (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A redacted amnesty record produced by the Western Australian Museum, June 24, 1993.

Outcomes from the Amnesty

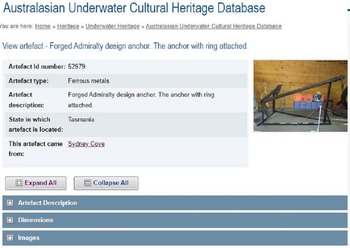

Approximately 20,000 previously unrecorded relics were declared during the amnesty period by a wide range of people, institutions, and businesses. The majority were reported in Western Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland, which roughly correlates with the jurisdictions with the highest levels of observed looting. The graphs below were compiled from amnesty-period data by Rodrigues (Reference Rodrigues2009a:101; Figure 3). Even at this time, many of the notified relics were not collected by the notifying individual because they had been inherited, traded, or donated to museums. Declared relics included “glassware, ships’ bells, watches, porthole scuttles, bolts, clay pipes, coins, personal possessions, various ships’ fittings, armaments, navigational instruments, ballast, ceramic objects, rigging-related artifacts, items related to hull structures, and various metal and wooden objects” (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2009a:100). In addition to the relics, “around 30 shipwrecks previously unknown to authorities were reported” (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2009a:100).

Figure 3. The top graph shows the number of artifacts declared from sites within each Jurisdiction, and bottom graph shows the number of wrecks looted versus total number of known wrecks within each state. (Graphs from Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2009a:101–102.)

AMNESTY AND OTHER RELIC MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Public Hesitancy to Notify Possession

Much of the extensive recovery of shipwreck relics by scuba divers and snorkelers from the 1950s through to the 1970s was illegal under the Navigation Act, property laws, or early underwater heritage legislation introduced by Western Australia. Relics were recovered for aesthetic or intrinsic values and were kept as souvenirs, with some sold for scrap metal, made into jewelry, used in house construction, melted down, or discarded (Henderson Reference Henderson1986; Rodrigues and Richards Reference Rodrigues and Richards2012). Government authorities had largely ignored the problem, but this changed with the introduction of the Shipwrecks Act, which actively controlled and protected these relics nationally. Once the members of the public became aware that their removal and possession of shipwreck relics was in fact illegal, there was, from 1976 to 1993, reluctance to come forward for fear of prosecution and concern that relics in their possession might be taken away from them and/or that their treatment of the relics would be an issue. This resulted in relics not being notified and a culture of noncompliance among some divers. The result of public hesitancy and the fact that an unknown number of items had been discarded, recycled, or lost, in addition to not being notified, makes it difficult to assess the scale of the impact of early divers on Australia's shipwreck heritage.

Unsystematic National Approach to Artifact Management

Although the amnesty was successful, with many previously unknown relics being notified, the subsequent management of the data and information collected was not well organized. Notification data was sometimes not of a sufficient quality to enable future identification: multiple artifacts were given identical text descriptions, and documentation standards were not consistently carried out in each jurisdiction (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2009a, Reference Rodrigues2009b). This situation was exacerbated by “the geographical widespread locations of custodians and their collections and so some agencies registered amnesty notifications based on paper declarations submitted” (Rodrigues and Richards Reference Rodrigues and Richards2012:78). Given that some amnesty object notification descriptions make it hard or impossible to identify relics, it consequently makes it “difficult to monitor custody transfers of objects between people” (Rodrigues and Richards Reference Rodrigues and Richards2012:78).

Conservation and Ongoing Relic Management

With the vast majority of notified relics requiring interventive and/or preventive conservation to stabilize an object's condition, the amnesty was an opportunity to collect typological and archaeological information as well as to assess an object's condition. There were not the financial resources or conservation technical skills nationally available to do this during the amnesty. The ongoing monitoring of the condition of notified relics in public possession remains largely nonexistent for the same reasons. This collection management failure by the Commonwealth and jurisdictions exists despite the fact that the minister had/has the power to give direction about the conservation of relics/artifacts and could/can seize those relics/artifacts that are not being maintained.

Challenges in Maintaining an Artifact Register

An important provision in the Shipwrecks Act (and duplicated and expanded in the later Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018, outlined below) is the inclusion of a provision requiring the minister to maintain a statutory register of sites and associated protected relics, along with documentation relating to that protection. In 1976, when the Shipwrecks Act came into force, access to computers was not common, and all information to develop a statutory register was recorded on paper forms or in ledger books, neither of which made it simple to track relic movements and possession. Only the West Australian and Victorian jurisdictions subsequently established an electronic register to track the movement and possession of relics registered during the amnesty.

At the time of the amnesty, the then-titled Australian National Shipwrecks Database (ANSDB) did not include the ability to store relic information or link that information to a site, and the records were either in paper form or stored in separate electronic spreadsheets by jurisdictions and the Commonwealth. As Rodrigues and Richards (Reference Rodrigues and Richards2012:81) stated, in “hindsight, . . . a centralised artefact registration database should have been set up to ensure consistency across the country thereby implementing greater control over the process.” In the years following the amnesty, there was little attempt to compile notification records or maintain their currency, and they soon became of limited value for determining the location of the artifacts and who had possession (Rodrigues and Richards Reference Rodrigues and Richards2012).

Lost Management and Research Opportunity

A lost research opportunity identified after the amnesty was the failure to undertake oral history recordings with notifiers to get better provenance information about notified relics (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2009a, Reference Rodrigues2009b). As mentioned above, only the Western Australian and Victorian jurisdictions undertook active management and research of their amnesty collection (Howell-Muers Reference Howell-Meurs1999; Philippou Reference Philippou2004), whereas the WA Museum (acting for the WA Delegate) singularly bore the largest burden of notification and permitting because old Dutch notified relics were regularly traded. The lost opportunity stemming from no active management and research has resulted in many people in possession, custody, and control of protected relics not being contacted, their contact details not being maintained, and the condition of relics in their possession being largely unknown. It has also meant that there has been little ongoing meaningful contact between archaeologists and persons in possession, custody, and control of protected relics.

Although jurisdictions, including the Commonwealth, have created these legacy problems, other individuals have demonstrated the research potential and benefits of the amnesty collections, particularly Rodrigues (Reference Rodrigues2007, Reference Rodrigues2009a, Reference Rodrigues2009b, Reference Rodrigues2010) in her PhD research, as well as Ellis (Reference Ellis2001), Fielding (Reference Fielding2003), Howell-Meurs (Reference Howell-Meurs1999), Knott (Reference Knott2001), McCarthy (Reference McCarthy, Shaw and Wilkins2006), McPhee (Reference McPhee2004), Philippou (Reference Philippou2004), and Rodrigues and Richards (Reference Rodrigues and Richards2012). However, little other research has been done on amnesty material to date.

Issues with Registration Certificates

Although the Shipwrecks Act was seen as a breakthrough in the protection and management of at least one thematic component of UCH, it did have some weakness in the management of protected relics. The Commonwealth drafters had not considered the need for registration certificates so that relics could be easily identified, even though the WA Museum had been issuing registration certificates for Dutch relics since 1964. The management of Commonwealth-protected relics continued to be reliant on handwritten WA Museum certificates until the ANSDB was redeveloped in 2009.

Working with Looters

The Commonwealth, at least since the amnesty, has taken the view of compliance versus enforcement and has largely tried to work with individuals to meet the notification and permitting objectives of the Shipwrecks Act. However, for individuals who are discovered to have taken relics from sites after their declaration of protection under the Shipwrecks Act, and/or who could be shown to have knowledge of the Shipwrecks Act and an intent to breach it, investigation for prosecution has always been pursued.

THE COMMONWEALTH TAKES THE LEAD AROUND 2006

From the late 1990s until 2006, the cooperative delivery of the Shipwrecks Act was faltering. A combination of Commonwealth issues remained, including high rotation of staff with no technical or policy background, diminishing funding, state and Commonwealth legislation, differing interpretations of the Act's operation and its impact on divers (Green Reference Green1995; Hosty Reference Hosty1987; Jeffery and Moran Reference Jeffery and Moran2001), limited HSP coordination and leadership (Viduka Reference Viduka2012, Reference Viduka2015), and state-level issues (Cooper Reference Cooper1998). The problems were magnified by the contemporaneous movement of the Act's administration between Commonwealth departments.

In 2006 the then Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage (now the Department of Agriculture, Water, and the Environment [the Department]) made a decision to address the problems and to take up the mantle of national leadership in Historic Shipwrecks. The internal reform resulted in the appointment of two staff, who, for the first time, had both qualifications in maritime archaeology and technical and policy backgrounds capable of strategically driving the HSP. The purpose of these appointments was large in scope and initially focused on rebuilding state and Northern Territory relations and engagement; reviewing the HSP; resolving funding issues to jurisdictions; initiating legislative reform; pursuing ratification of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 2001 Convention for the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (see UNESCO 2001); improving compliance and enforcement capacity and activity; and developing a database to more effectively and consistently administer the Shipwrecks Act (Viduka Reference Viduka2012).

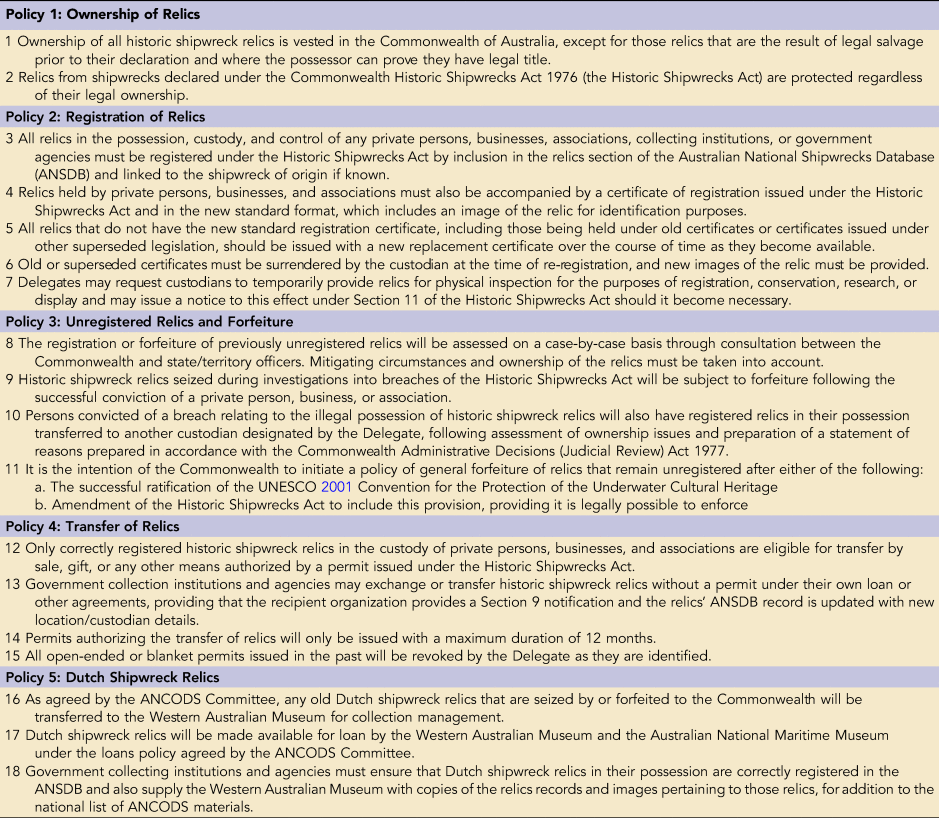

By 2009, the Department had launched a new national database—the ANSDB—to act as the statutory register (see below) and completed a public review of the Shipwrecks Act. In 2010, the Commonwealth, States, and the Northern Territory endorsed the Australian UCH Inter Governmental Agreement (Australian Government Reference Government2010) and the Department working with the Delegates formalized the minister's Delegates policy in regard to relics in 2012 (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Historic Shipwrecks Relics Policy circa 2012.

Relic-related implications of the AUCH IGA, in which the jurisdictions agreed to the Australian Government's consideration of ratification of the 2001 Convention, include stopping future trade of protected relics that are not legally notified at the time of ratification. Another implication is that the future recovery of relics from protected sites would be governed by proponents meeting the requirements of updated legislation and of the 2001 Convention's Annex Rules (UNESCO 1996, 2001).

NEW LEGISLATION TO PROTECT AUSTRALIA'S UCH

An additional positive outcome was drafting new legislation to protect all UCH. The Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (the UCH Act) and associated Underwater Cultural Heritage Rules 2018 (UCH Rules) were drafted to modernize and build on the successful functions of the Shipwrecks Act. Consequently, they contain many similar provisions and address issues of the Shipwrecks Act identified from responses to the 2009 public review and to meet future policy needs (Australian Government Reference Government2009; Viduka Reference Viduka2022). The identified issues related to relics were that the Shipwrecks Act

• Only protected shipwrecks and their associated relics

• Treated human remains identically to a relic

• Failed to protect the natural environment components of sites

• Was inconsistent with international law (i.e., United Nations Reference Nations1982)

• Had compliance provisions that were outdated and increasingly unenforceable

The UCH Act came into force on July 1, 2019, replacing the Shipwrecks Act. In relation to relics (now legally called “articles”), the UCH Act includes powers for

• Prohibiting impacts on sites, including the natural environment component and the recovery of artifacts, without a permit

• Giving the minister powers to gather information on the location of artifacts and to give directions in relation to their possession and care

• Recognizing and protecting human remains as separate from other artifacts

• Enabling the appointment of Inspectors to enforce the UCH Act (including powers to require persons in possession, custody, and control of protected UCH to produce their permits)

• Requiring the minister to maintain a register of UCH

• Regulating the trade, possession, import, and export of protected artifacts, even UCH artifacts from another country

• Enabling protection of Australia's UCH in waters outside Australia from actions by Australians

EXTENDING PROTECTION AND MANAGEMENT TO ASSOCIATED ARTIFACTS

To broadly align Australia with the requirements of the 2001 Convention, a key requirement was to extend protection to all UCH. Stemming from the Seas and Submerged Lands Act 1973 (Commonwealth) and the Offshore Constitutional Settlement 1979 (Commonwealth; Attorney General's Department [AGD] 2022), the UCH Act has a split jurisdiction for different types of UCH. Historic shipwrecks are protected by the Commonwealth from the Lowest Astronomical Tide (LAT) along the coastline out to 200 nm, whereas submerged aircraft and other UCH are only protected by Commonwealth legislation from 3 nm out to 200 nm. Between the LAT and 3 nm, the States and the Northern Territory protect submerged aircraft and other UCH as they do landward of the LAT for all UCH.

With the commencement of the UCH Act, any aircraft that had been in waters for more than 75 years became automatically protected along with its associated artifacts. Given that the majority of such artifacts were from World War II, in 2020, they all became protected, and any artifacts previously recovered now needed to be declared to the minister to be in legal possession.

KEY FEATURES OF THE UCH ACT 2018

Ownership of UCH

The primary objective of the Shipwrecks Act and the UCH Act that replaced it is the protection of UCH, not issues of ownership. However, the UCH Act contains three declarations concerning ownership: s.50—Dutch shipwrecks and associated artifacts; s.51—other underwater cultural heritage; and s.52—ownership by the Commonwealth of its sovereign/defense vessels, sunken aircraft, and associated artifacts. It also contains provisions to assign ownership of protected UCH, if necessary, but this does not remove it from the protection of the UCH Act.

MANAGEMENT OF PROTECTED ARTIFACTS

Australasian Underwater Cultural Heritage Database

The Australian National Shipwrecks Database (ANSDB) has transformed from a pre-computer-era paper-based record to the current Australasian Underwater Cultural Heritage Database (Australian Government Reference Government2021). From 1986 to the late 1990s the database was largely maintained by the WA Museum. Transferred to the Australian Government and not updated, by 2006 the ANSDB was technically obsolete and “had 53 fields for shipwreck information, no ability to record information about shipwreck relics, limited search functionality, no on-line management capability and no connection to a Geographic Information System (GIS)” (Luckman and Viduka Reference Luckman and Viduka2013:76).

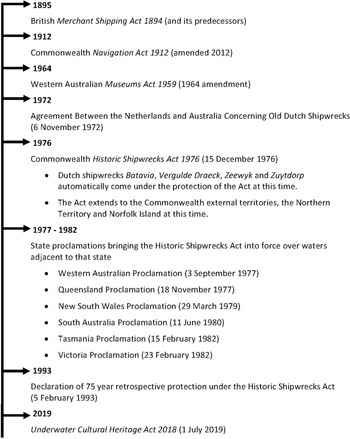

In the years 2007–2009, the Department significantly expanded and improved the ANSDB with new data fields and functionalities to assist the collaborative national administration of the Shipwrecks Act (Luckman and Viduka Reference Luckman and Viduka2013). In 2013, the AUCHD had 411 data fields, Today, it has approximately 500, along with a detailed user manual and metadata guide (Luckman and Viduka Reference Luckman and Viduka2013). The relational database links sites, artifacts, notifications, permits, and client records, and it includes a publicly accessible Google Maps–based geographical information system (GIS) and an internal user ArcGIS functionality (Luckman and Viduka Reference Luckman and Viduka2013). A screenshot of a typical shipwreck artifact-record landing page is shown in Figure 4. All statutory actions occur within the database. Notification and permit work items come through to the department for assessment prior to being sent out to the relevant jurisdictions for processing. This now gives the Commonwealth global oversight of all statutory activity, significantly improved search functionality, and an ability to ensure consistency of decision-making, conditions, and documentation standards. Protected artifacts not included in the AUCHD may be subject to seizure.

Figure 4. This anchor artifact is from the Sydney Cove (1797). This screenshot shows the typical information on an artifact record landing page.

The UCH Act s.48 specifically further defined what was required in the minister's statutory register, including permits (previously not legislated), any other matters prescribed by the UCH Rules, and matters related to the administration and operation of the register. New provisions in the UCH Act enable the control of the export of protected UCH through permit and the control of the import of UCH through permit to ensure that no looted material enters the country.

Permitting of Artifacts

As stated above, under the Shipwrecks Act, the notification and permitting requirements for transferring a protected artifact by sale were cumbersome. The UCH Act has embraced a simplified transferable permit process to reduce regulatory burden on the possessor and the AUCHP. Of the approximately 500,000 recovered UCH artifacts protected by the UCH Act (most of which are located in museums), about 10% are in public possession, custody, and control and eligible to be traded or sold. Under the UCH Act, the sale or transfer of protected artifacts is managed through permit (sections 24[2]; 27[3]; 25[4]; 39[1]; 48[3][d] and [e], and 48[4][c]), and persons are obliged to notify the minister of their name and their current home address should they receive possession, custody, and control of a protected artifact from another person. The artifact's permit must be transferred with the artifact. The minister retains the power, for the purposes of managing protected artifacts (sections 38 and 39), to communicate to the person who has possession, custody, and control of a protected artifact and to give directions for their display, storage, or conservation. The updated transferrable permit system has removed the necessity for identification certificates because the new permit design incorporates scaled images of the artifacts.

Under Australian Government policy, until Australia ratifies the 2001 Convention, persons are encouraged to notify possession of previously unnotified relics, thereby preserving a person's proprietary rights and enabling that artifact to be legally traded in the future.

Exporting and Importing UCH

Although the Shipwrecks Act contained a provision requiring a permit authorizing the removal of protected UCH from Australia, there was no provision that controlled the import of UCH from other countries. This serious omission was exposed first in 2001 when artifacts raised from the Tek Sing shipwreck off Indonesia were detected in transit within Australia on their way to Europe and then again around 2015 in an incident involving illegally recovered Australian, Dutch, British, and Japanese UCH artifacts that were mainly from sovereign wrecks in the Java Sea. To directly address this legislative lacuna in protection and to align with the 2001 Convention, s.52 of the UCH Act was included. Furthermore, the UCH Act now contains provisions to control the export of Australian protected UCH, importation of UCH of a foreign country, and importation of artifacts from Australian UCH sites located outside Australian waters.

A DECISION-MAKING FRAMEWORK TO DETERMINE LEGAL POSSESSION

As may be appreciated, the management of Australia's protected shipwreck relics and (later) other protected UCH artifacts requires an administered approach to achieve both the letter of the law and an appropriately proportioned compliance outcome suitable to an offense. Certainly, with the determination of any prior knowledge or intent to breach legislation by an individual or business, the full efforts of the Department to prosecute come into play. However, it is not uncommon for previously unnotified objects to be brought forward by family members of a deceased person. To assist individuals collaboratively administering the UCH Act, a timeline of the legal administration of shipwrecks and relics/artifacts in Australia (Figure 5) and a statutory decision-making flowchart for the registration and possession of protected relics/articles were prepared (Figure 6). This flowchart document includes references to actions that may be taken.

Figure 5. Timeline of the legal administration of shipwrecks and relics in Australia.

Figure 6. Statutory decision-making chart for the registration and possession of protected Historic Shipwreck Relics.

COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT OF PROTECTED RELICS/ARTIFACTS

Should a potential breach of the UCH Act come to the attention of the jurisdictions, the jurisdiction is required to refer the matter for investigation to the Commonwealth. Desktop assessment is undertaken within the section administering the UCH Act. Matters are referred internally for further investigation to the Compliance Branch if there is reasonable suspicion of knowledge and intent of serious noncompliance. Otherwise, an administered approach is usually taken to resolve the issue.

Online Auctions and Sales

Since the 2000s, the internet has made it simple to offer artifacts for sale, including those that are illegal, but it exposes them to greater scrutiny by management authorities and police forces. Consequently, the detection of illegal artifacts has greatly increased. Prior to the internet, sales were mostly undertaken by secondhand dealers, auction houses, or direct personal contact between individuals, which were extremely difficult to detect. New UCH Act requirements have been adopted and now require the artifact permit number to be advertised with the artifact when listed for trade or sale online.

Ban on “Future” Sale and Trade of Protected Relics

Certainly, the issue of facilitating the sale/trade of protected relics/artifacts is one that the Commonwealth has faced during its consideration of ratification of the 2001 Convention. The 2001 Convention was brought in to stop the contemporary looting of sites and the subsequent trade and sale of those artifacts. Although Australia currently aligns broadly with the 2001 Convention, we do need to facilitate an ongoing trade and sale of notified protected relics recovered prior to the Shipwrecks Act introduction so as to respect the property rights of individuals. Should Australia ratify the 2001 Convention, the onus of proof on an individual to demonstrate that a previously unnotified relic was collected prior to the sites’ protection will be significant. In the future, failure to meet that test could result in seizure.

FUTURE ARTIFACT MANAGEMENT IDEAS

In 2021, the Department started scoping the design and development of a new database that will have a new front-end user interface and potentially many new functionalities to assist with the management of protected artifacts (some of these ideas are outlined below). These proposed modifications in our artifact management, capitalizing on improved processes and new technology capacities, will improve the management of protected artifacts and will be a positive step along the iterative path of adaptation required to manage this complex legacy issue.

QR Codes

Facilitating rapid access to file records for individual artifacts, the Department is considering introducing technology such as QR codes, which would be printed on each transferrable permit. Using phone technology, a UCH Inspector could be well placed to determine easily if an artifact described on the transferrable permit is the artifact physically observed, or if the artifact is listed for sale. It could also assist persons with notifying their possession of artifacts if combined with a mobile application. To implement this improvement, reissuing of all permits issued since the introduction of the UCH Act will be a consequence and an additional administrative burden for jurisdictions and the Commonwealth.

Annual Automated E-mails

Due to the recognition that there has been a significant ongoing failure to maintain accurate records of the individual in possession, custody, and control of protected artifacts and the condition of those artifacts, with the development of the new database, an automated e-mailing functionality will be included to audit the possession of individuals holding protected artifacts. This will help the Department start to engage actively with custodians, to understand the condition of artifacts, and to identify potential breaches of the UCH Act.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This article has outlined the legislative, legal, policy, and administrative practices that have been used to protect shipwreck artifacts from 1976 and other UCH artifacts since mid-2019. The legacy issues stemming from administering legislation that manages artifacts with three different retrospective commencement dates for different classes of sites (1976, 1993, and 2019) are significant, and their impact continues today. Issues that are still being addressed include the initial lack of national consistency in documenting notified artifacts, the acceptance of minimal descriptions for artifacts without scales or images during the amnesty by some jurisdictions, the initial use of paper-based systems to record artifacts, and a failure to maintain collected records.

Certainly, the WA Museum has done much to manage protected relics since 1964, particularly by leading the bulk of the notification, documenting, and permitting processes and by maintaining a record of the transfer of Commonwealth protected relics since 1976. Only since 2009 has the Commonwealth itself—with the introduction of the modernized AUCHD and with the 2019 introduction of the UCH Act—been in a position to proactively improve both the quality of notified artifact data and the artifacts’ statutory management processes. Even with that administrative improvement, knowing who has possession of notified protected artifacts in public control, where those artifacts are, and what the statutory obligations on individuals to maintain a protected artifact's condition are remains a challenge. Certainly, much can be done to improve collaboration between archaeologists and artifact custodians and to better understand the quality of care being given to artifacts in the possession of individuals.

As illustrated in this article, Australian Government UCH artifact policy and administrative processes are adaptive and subject to constant review and refinement to meet the objectives of the UCH Act through encouraging individual compliance, improving statutory processes and outcomes, and ensuring appropriately proportioned deterrence to noncompliance. It is important to remember that the primary reason for this significant work activity was to enable research into these collected artifacts to learn more about our impacted shipwreck heritage. With better documentation methods for notified artifacts and other administrative improvements of the UCH Act, it is hoped that this important research objective will be reinvigorated.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all our previous colleagues who administered the Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976 and who collaborate today in administering the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were used in this article.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.