Introduction

Interest in the role of social mediaFootnote 1 (SM) use in young people’s wellbeing and mental health has grown over the last decade, and a number of researchers have attempted to link the increase in mental health difficulties in this age-group with the uptake of SM, or digital screen use more generally (Twenge et al., Reference Twenge, Joiner, Rogers and Martin2018; Twenge and Campbell, Reference Twenge and Campbell2018). In the context of healthy ongoing debate (Orben and Przybylski Reference Orben and Przybylski2020a; Twenge et al., Reference Twenge, Haidt, Joiner and Campbell2020), however, a critical evaluation of the existing evidence base suggests a complex pattern of associations between SM use and wellbeing in children and adolescents, including effects that are relatively small in size, mediated/moderated by other factors, and of unclear direction of causality (Orben et al., Reference Orben, Dienlin and Przybylski2019). In addition, alongside the more commonly considered negative effects of SM, a number of positive effects of SM have also been posited (Uhls et al., Reference Uhls, Ellison and Subrahmanyam2017), with some evidence even suggesting that online opportunities and risks may be closely linked (Hollis et al., Reference Hollis, Livingstone and Sonuga-Barke2020; Livingstone and Helsper, Reference Livingstone and Helsper2010). Consequently, there is an emerging consensus that how an individual engages with SM (and digital technologies more generally) is likely to be more important than how much, i.e. frequency, intensity or duration (Blum-Ross and Livingstone, Reference Blum-Ross and Livingstone2018; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Telzer and Prinstein2020; Orben et al., Reference Orben, Weinstein and Przybylski2020b), and relatedly, that there is a need to identify digital contexts and patterns of online interactions that are differentially linked to positive and negative outcomes (Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020).

This more nuanced perspective and evaluation of SM’s relative risks and benefits has been slow to filter into mainstream clinical and educational literature, guidelines or practice. Thus, when it comes to the online world, much of the work within applied psychology has, to date, traditionally focused on extreme and highly problematic patterns of use, i.e. the field has adopted a ‘concern-centric’ approach (Orben et al., Reference Orben, Weinstein and Przybylski2020b), although this is arguably changing (Aboujaoude, Reference Aboujaoude2010; Kuss and Lopez-Fernandez, Reference Kuss and Lopez-Fernandez2016; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ren, Long, Liu and Liu2019). Furthermore, a number of professional bodies have published guidelines on how to manage the online world of children and adolescents, and these have focused almost exclusively on the putative negative effects of SM use, despite the potential value in harnessing its benefits also (AAP Council on Communications and Media, 2016; Dubicka and Theodosiou, Reference Dubicka and Theodosiou2020; Viner et al., Reference Viner, Davie and Firth2019).

Against the backdrop of this growing interest it has been argued that the area lacks a firm theoretical foundation, despite the essential role that this plays in the development and integration of a field (Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020; Orben, 2018; Orben et al., Reference Orben, Weinstein and Przybylski2020b). In actuality, a number of theoretical models of SM use (and digital technology use more generally) do exist; however, these have typically emerged from within the fields of computer-mediated communication and media, developmental and organisational psychology, rather than clinical psychology, and as such, have tended to be non-clinical in nature, often concentrating on more general variables such as (for example) motivations for technology uptake, use or continued use, e.g. the Uses and Gratifications theory (Ruggiero, Reference Ruggiero2000), the Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour (Baker, Reference Baker2010), LaRose and Eastin’s (Reference LaRose and Eastin2004) Social Cognitive Theory of Internet Uses and Gratifications, the Technology Acceptance Model (Marangunić and Granić Reference Marangunić and Granić2015), and the Technology Integration Model (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Ellis and Ziegler2018).

A number of other models have focused on how the online world creates novel channels for communication and the implications of this for the user’s sense of self, their sense of others, as well as the nature of their social interactions, e.g. the Co-construction Model (Subrahmanyam and Šmahel, Reference Subrahmanyam and Šmahel2011e), the Self-Effects Model (Valkenburg, Reference Valkenburg2017), the Differential Susceptibility to Media Effects Model (Valkenburg and Peter, Reference Valkenburg and Peter2013) and the Social Information Processing Theory (Walther, Reference Walther1992; Walther, Reference Walther, Braithwaite and Schrodt2015). Whilst some of these have potential implications for clinical practice, and have informed our thinking as well as much of the literature that we draw upon, such links to clinical practice are typically implicit rather than explicit. Where an explicit clinical perspective has been taken in the construction of a SM use model, this has tended to focus on extreme patterns of use, such that the primary issue relates to problematic technology and/or SM use itself (Caplan, Reference Caplan2005; Davis, Reference Davis2001; Turel and Qahri-Saremi, Reference Turel and Qahri-Saremi2016; Wegmann and Brand, Reference Wegmann and Brand2019).

Thus, we would argue that whilst existing models and theoretical frameworks of SM use are highly informative, with a rich body of research underpinning them, they are of limited utility (as they stand) to the typical mental health clinician working in a general community mental health setting who wants practical guidance on how to harness the benefits and ameliorate the harms of SM use. For example, they do not lend themselves readily to the identification of targets for intervention, and because of their complexity and limitations in scope, are not suitable for sharing with service users themselves. Thus, we would argue that for a model to be of maximum clinical utility it should be intelligible and useful to the therapist and the client alike, bridging the gap between theory and practice, model and formulation, facilitating a shared understanding of the individual’s presenting difficulties in an empowering way that opens up opportunities for behavioural change (Division of Clinical Psychology, 2011). [See also Ngai et al. (Reference Ngai, Tao and Moon2015) for a review on theories, constructs and conceptual frameworks that have been drawn upon (more broadly) within the SM literature, and McFarland and Ployhart (Reference McFarland and Ployhart2015), Meier and Reinecke (Reference Meier and Reinecke2020) and Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Holden and Ariati2021) for useful frameworks to conceptualise and systematise existing research.]

In response to this gap in the literature, this paper describes a trans-diagnostic cognitive behavioural conceptualisation of the positive and negative effects of SM use on mental health and wellbeing in adolescents, with a focus on social/inter-personal processes and their interaction with common mental health difficulties, such as anxiety and depression. Drawing on our combined clinical experience of working with young people, an integration of the extant evidence base and existing theoretical frameworks of SM use and common mental health difficulties, its aim is not to pathologise everyday patterns of SM use, but instead, to achieve the following: (i) to act as a model for clinicians to integrate and make sense of relevant research from a clinical perspective, (ii) to act as an aide for clinicians to collaboratively formulate (and share) with young people the role of SM in their mental health difficulties, both in terms of risks to negotiate as well as benefits to harness, in order to (iii) direct treatment (where indicated), and (iv) in the long-term, inform the development of strategies and/or interventions to help individuals shape their online lives in a healthy way that is in line with their needs, goals and values. Consistent with these aims we recognise that the conceptualisation is an early working model to be updated iteratively as key components are either supported or refuted through empirical testing.

The paper begins with a brief overview of social processes and SM use in adolescence in order to locate and contextualise the focus of the conceptualisation, before exploring the existing literature on the links between SM use and mental health. It then presents an overview of the main theoretical foundations from which the conceptualisation explicitly draws, before presenting a précis of the conceptualisation, as well as a more in-depth consideration of each of its core components. Finally, we close with a discussion of the implications of the model for clinical practice.

Social processes and social media use in adolescence

Adolescence, defined here as the period between 10 and 24 years of age, is a broad window of development bridging childhood and adulthood, which is characterised by profound biological, psychological and social change (Blakemore, Reference Blakemore2018; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Blum and Giedd2009). It is a period of great opportunity and promise, but also vulnerability, with approximately three-quarters of all lifetime psychological disorders emerging by the end of this stage (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee and Ustün2007).

One of the primary challenges for adolescence, many have posited, is identity formation, a profoundly social process by which the young person must typically individuate from a family unit and establish a coherent identity that is embedded within a network of peer connections (Erikson, Reference Erikson1968; Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020). Whilst there is great inter-individual variation in trajectories between adolescents, during this period the individual commonly faces a multitude of external challenges that must be negotiated, from leaving the family home and learning to live independently, to earning a wage and establishing peer friendships as well as sexual and romantic partners (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne and Patton2018). In parallel, the adolescent is also confronted with a myriad of internal/biological changes, from the development of secondary sexual characteristics under hormonal control, to a protracted process of brain maturation (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Ahmed and Blakemore2020).

Critically, some of the last areas of the brain to mature during development are located within the ‘social brain’, i.e. networks thought to underpin social cognitive processes such as perspective taking, emotional regulation and the management of peer influence (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Ahmed and Blakemore2020). Psychologically, this is reflected in a period of heightened social sensitivity, during which peer influence and vulnerability to the negative effects of social isolation and peer rejection are elevated (Orben et al., Reference Orben, Tomova and Blakemore2020a; Tomova et al., Reference Tomova, Andrews and Blakemore2021), with social interactions playing a crucial role in the development of identity (Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020; Ragelienė, Reference Ragelienė2016). Indeed, a wealth of research has linked the quality and nature of peer interactions in adolescence with a range of psychological, educational, physical health and behavioural outcomes (Almquist, Reference Almquist2009; Almquist and Östberg, Reference Almquist and Östberg2013; Menting et al., Reference Menting, Van Lier, Koot, Pardini and Loeber2015; Modin et al., Reference Modin, Östberg and Almquist2011).

Risk-taking, novelty-seeking, impulsivity, exploration and experimentation are also elevated during adolescence relative to adulthood, with social factors thought to play a crucial role (Tomova et al., Reference Tomova, Andrews and Blakemore2021). For example, adolescents are more likely than adults to take risks when in the presence of peers (Gardner and Steinberg, Reference Gardner and Steinberg2005; Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Lane, Tapscott and Gentile2011), and this effect is more pronounced when the peers report a preference for risk-taking behaviour (Bingham et al., Reference Bingham, Simons-Morton, Pradhan, Li, Almani, Falk, Shope, Buckley, Ouimet and Albert2016). Two distinct but interacting psychological processes have been hypothesised as important to an understanding of adolescent risk-taking: impulsivity and sensation-seeking. Thus, according to the Life-span Wisdom Model (Romer, Reference Romer2010; Romer et al., Reference Romer, Reyna and Satterthwaite2017), there is a gradual reduction in risk-taking and impulsivity between childhood and adulthood, which is underpinned by the development of executive function skills and a maturation of the prefrontal cortex (Green et al., Reference Green, Fry and Myerson1994). This protracted development of self-regulatory skills is thought to underpin some of the more maladaptive impulsive behaviours commonly seen in childhood and early adolescence. In parallel, there is an increase in sensation-seeking that follows an inverted U-shape function and peaks around adolescence. This coincides with increased activity in limbic and prefrontal dopaminergic networks associated with reward-sensitivity (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Taylor and Potenza2003; Romer and Hennessy, Reference Romer and Hennessy2007). In contrast to the aforementioned process, whilst conferring additional risk, this is thought to be partially adaptive, driving an exploration of the environment that is critical for learning (Romer, Reference Romer2010; Romer et al., Reference Romer, Reyna and Satterthwaite2017) and in some contexts may be optimal (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, McKay, Sebastian and Balsters2020). Thus, risk-taking and exploration/learning may be two sides of the same coin.

Against this backdrop of heightened risk-taking and peer-influence, it is not surprising that a number of authors have hypothesised the potentially transformative impact of SM (and the internet more generally) on young people’s social interactions, and by inference, identity formation (Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020; Subrahmanyam and Šmahel Reference Subrahmanyam and Šmahel2011b) and social and emotional wellbeing; see Spies Shapiro and Margolin (Reference Spies Shapiro and Margolin2014) for a review, and Crone and Konijn (Reference Crone and Konijn2018) also. Thus, the latest (pre-COVID) worldwide census data (from January to March 2010) suggest that Generation Z (aged 16 to 23 years at present) are the heaviest SM users of all, currently using SM for an average of 2.7 hours each day across an average of 8.5 SM accounts (GlobalWebIndex, 2020). Furthermore, adolescents with a diagnosed ‘mental disorder’ are more likely to use SM every day and for longer than those without a diagnosis (NHS Digital, 2017). Whilst Amy Orben has written articulately about the repeating cycle of panic that follows the emergence of any new technology (Orben, 2020b), SM undoubtedly offers novel opportunities for social experimentation, exploration and connection, but also, fresh challenges and risks, which at the very least, argue for close attention to be given to the online lives of young people presenting to mental health services.

Drawing on a contextual approach that recognises the complex interaction that occurs between the individual, their pattern of SM use and the nature of the technology with which they are engaging (as well as the broader social context in which this occurs) (Vanden Abeele, Reference Vanden Abeele2020; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Telzer and Prinstein2020), the cognitive behavioural conceptualisation we present does not assume radically different processes during adolescence (relative to other life stages), but instead, acknowledges that key social processes may be particularly pertinent and play a more central role for this age group. Thus, issues of acceptance and belonging and the balance between individual and group identity affect us all, irrespective of life stage. Likewise, the online world opens up novel ways of interacting with others for the adolescent and adult alike, with all the potential risks and benefits that these bring. Whilst a comprehensive review of research into such risks and benefits lies beyond the remit of this paper, we provide a brief overview of some of the key concepts and processes implicated below. Where available this draws on studies undertaken with adolescents; however, in view of the relative paucity of such research we also draw from a wider body of literature that includes studies undertaken with adults.

Social media use and mental health

Interpretation of existing research into the association between SM use and mental health is complicated by the fact that extant studies have explored an array of SM constructs (from self-reported time spent on any SM site, to defined behaviours undertaken on specific platforms) and mental health constructs (from specific disorders, to general risk factors for psychopathology), which are likely to exhibit distinct patterns of association. In response, Meier and Reinecke (Reference Meier and Reinecke2020) developed two organising frameworks to ‘systematize conceptual and operational approaches’ (p. 1) to computer-mediated communication (CMC) (including SM use) and mental health research.

The first framework, which focused on CMC, defined four ‘channel-centred’ levels of analysis, which included the device (e.g. smartphone), type of application (e.g. SM), application brand (e.g. Facebook), and application/brand feature (e.g. private messaging), in addition to two ‘communication-centred’ levels of analysis, which included the nature of the interaction (e.g. active vs passive engagement) as well as the message/communication itself. The second framework, which focused on mental health, distinguished between psychopathology (which they broke down further into internalising and externalising psychopathology, e.g. anxiety and aggression, respectively), and psychological wellbeing.

With respect to the existing evidence base into the association between SM use and mental health/wellbeing, a great deal has focused on the level of application or application brand (channel-centred research), e.g. time spent on SM, frequency of use, or intensity of use (Meier and Reinecke, Reference Meier and Reinecke2020). Within this research, however, the majority of studies have drawn on single-platform data, such as studies of Facebook use or cross-platform data that do not differentiate between platforms, thereby precluding identification of differential effects based on platform brand, let alone brand features (Schønning et al., Reference Schønning, Hjetland, Aarø and Skogen2020).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of overall levels of SM use (i.e. application level analyses) are relatively consistent, however, with evidence for a weak association between higher usage and poorer mental health (Abi-Jaoude et al., Reference Abi-Jaoude, Treurnicht Naylor and Pignatiello2020; Orben, Reference Orben2020a), including symptoms of depression, anxiety and general distress (Abi-Jaoude et al., Reference Abi-Jaoude, Treurnicht Naylor and Pignatiello2020; Keles et al., Reference Keles, McCrae and Grealish2019; McCrae et al., Reference McCrae, Gettings and Purssell2017; Orben, Reference Orben2020a). In a meta-review of meta-analyses within the field, Meier and Reinecke (Reference Meier and Reinecke2020) found that individuals who used social network sites more intensely reported more internalising psychopathology, with an effect size in the range of r ≈ 0.05–0.2. Evidence therein, however, did not support associations between overall levels of social network site use and wellbeing/life satisfaction (as opposed to psychopathology), and no meta-analyses were found to have explored SM’s link to externalising psychopathology. See Valkenburg, Meier, and Beyens (n.d.) also.

With respect to directions of causality, although relatively rare (Orben, Reference Orben2020a), where longitudinal or experimental methods have been employed, the evidence is mixed, suggesting possible bidirectional/reciprocal effects; thus, whilst high levels of SM use may impact negatively on mental health, poorer mental health may also drive increased SM use (Aalbers et al., Reference Aalbers, McNally, Heeren, de Wit and Fried2019; Frison and Eggermont, Reference Frison and Eggermont2017; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Marx, Lipson and Young2018; Mosquera et al., Reference Mosquera, Odunowo, McNamara, Guo and Petrie2020; Orben and Przybylski, Reference Orben and Przybylski2019).

Putative mechanisms underlying the proposed harms of SM use

A number of mechanisms underlying associations between SM use and poorer mental health have been hypothesised. One common idea, known as the social displacement hypothesis, proposes that online activity competes for time that would otherwise be spent engaged in what is presumed to be healthier or more productive activities, such as sleeping, studying or socialising, the latter with potential implications for social development. However, evidence for the social displacement hypothesis is weak (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Kearney and Xing2019b; Valkenburg and Peter Reference Valkenburg and Peter2007), and it is likely that for some, SM actually facilitates social interactions, both online and offline (Valkenburg and Peter Reference Valkenburg and Peter2007); more on this below. Further, one study concluded that SM in fact displaces neutral or unpleasant activities rather than pleasurable or rewarding ones (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Johnson and Ross2019a).

In contrast, evidence for sleep disruption and/or displacement of sleep amongst heavy SM users (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Biello and Woods2019), and heavy digital screen users more generally, is relatively robust (Orben and Przybylski, Reference Orben and Przybylski2020b), although reported effect sizes are small (Orben and Przybylski, Reference Orben and Przybylski2020b). This is of potential interest here as sleep disturbance has been linked to a number of social difficulties (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Mendes and Prather2017), as well as a wide range of mental health disorders during adolescence (Tarokh et al., Reference Tarokh, Saletin and Carskadon2016). However, once again, experimental evidence indicates a potential bidirectional causal relationship (Bartel et al., Reference Bartel, Scheeren and Gradisar2019; Exelmans and Van den Bulck, Reference Exelmans and Van den Bulck2016; Tavernier and Willoughby, Reference Tavernier and Willoughby2014).

Perhaps the most commonly explored ‘communication-centred’ factors linked to negative outcomes are online social comparisons, and potentially relatedly, passive use. Thus, social comparisons theory (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954) proposes that our sense of self is derived, in part, from how we judge ourselves to be doing in comparison with others, and high levels of online upward social comparisons have been linked to poor self-esteem and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker and Sacker2018; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhou, Yang, Kong, Niu and Fan2017b; Schmuck et al., Reference Schmuck, Karsay, Matthes and Stevic2019; Tibber et al., Reference Tibber, Zhao and Butler2020; Vogel et al., Reference Vogel, Rose, Roberts and Eckles2014; Vogel et al., Reference Vogel, Rose, Okdie, Eckles and Franz2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Gaskin and Hawk2017), potentially in a causal manner (Vogel et al., Reference Vogel, Rose, Roberts and Eckles2014). Furthermore, in a meta-review by Meier and Reinecke (Reference Meier and Reinecke2020), the authors reported a small association between higher social comparisons on social network sites and symptoms of depression (r = 0.23; 95% CIs = 0.12, 0.34), which was greater for upward social comparisons (r = 0.33; 95% CIs = 0.20, 0.47), i.e. comparisons made with those perceived as better off than oneself.

With respect to passive SM use (e.g. scrolling or browsing), it has been proposed that this is linked to more negative outcomes than active use (e.g. self-disclosure and online exchanges with others), with the association potentially being causal (Frison and Eggermont, Reference Frison and Eggermont2016; Frison and Eggermont, Reference Frison and Eggermont2017; Kim and Lee Reference Kim and Lee2011; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Timpano, Tran and Joormann2015; Verduyn et al., Reference Verduyn, Lee, Park, Shablack, Orvell, Bayer, Ybarra, Jonides and Kross2015; Verduyn et al., Reference Verduyn, Ybarra, Résibois, Jonides and Kross2017; Wang Reference Wang2013; Wenninger et al., Reference Wenninger, Krasnova and Buxmann2014). In fact, the negative effects of passive use and social comparisons may be linked, as passive use is itself associated with higher levels of social comparisons and associated feelings of envy (Appel et al., Reference Appel, Gerlach and Crusius2016; Krasnova et al., Reference Krasnova, Widjaja, Buxmann, Wenninger and Benbasat2015; Tandoc et al., Reference Tandoc, Ferrucci and Duffy2015; Verduyn et al., Reference Verduyn, Lee, Park, Shablack, Orvell, Bayer, Ybarra, Jonides and Kross2015; Verduyn et al., Reference Verduyn, Ybarra, Résibois, Jonides and Kross2017).

Consistent with the validity of an active/passive distinction, in their meta-review Meier and Reinecke (Reference Meier and Reinecke2020) found that whilst active ‘interactions’ on social network sites (e.g. replying, commenting and liking) were related to positive wellbeing (r = 0.14, 95% CIs = 0.08, 0.2), more passive ‘content consumption’ (e.g. browsing, searching, monitoring) was linked to negative wellbeing (r = –0.14, 95% CIs = –0.2, –0.8). However, the authors reported that the evidence for associations between interaction level factors (including active vs passive use) and psychopathology (rather than wellbeing) was ‘scarce and inconsistent’ (p. 19). Relatedly, a recent paper reviewing the literature on active/passive use failed to find evidence for its association with wellbeing or mental health, leading the authors to conclude that such a distinction may be too coarse (Valkenburg, Driel and Beyens, n.d.). Other authors have similarly critiqued a simple active/passive dichotomy (Kross et al., Reference Kross, Verduyn, Sheppes, Costello, Jonides and Ybarra2021; Meier et al., Reference Meier, Gilbert, Börner and Possler2020), suggesting that precisely what is being actively/passively engaged with in such interactions may be crucial (Valkenburg, Driel and Beyens, n.d.).

Speaking to this, in their overview of the literature, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Holden and Ariati2021) proposed that passive viewing of one’s own profile may actually increase self-esteem, most probably because of the heavily curated nature of online profiles (including one’s own), which means that the self is portrayed in a positive light (Gonzales and Hancock, Reference Gonzales and Hancock2011). In addition, they noted that even where passive use does lead to social comparisons, the nature of these social comparisons may be critical. Thus Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Holden and Ariati2021) suggested that whilst judgemental comparisons, e.g. comparing one’s attractiveness or wealth to others’, are typically associated with negative outcomes, non-judgemental comparisons, e.g. of opinions and perspectives for informational purposes, may actually lead to mental health benefits (Park and Baek, Reference Park and Baek2018). Thus, passive use may be problematic specifically in instances where it leads to judgemental social comparisons.

Another possible mechanism of interest driving the association between SM use and poor mental health, which has received relatively little research attention to date, involves the potential for the nature of online communication to amplify or exacerbate maladaptive cognitions and/or facilitate problematic behaviours associated with pre-existing mental health difficulties and/or specific personality structures (Chohan and D’Souza, Reference Chohan and D’Souza2020). For example, online symptom-checking may fuel health anxiety (Doherty-Torstrick et al., Reference Doherty-Torstrick, Walton and Fallon2016; McMullan et al., Reference McMullan, Berle, Arnáez and Starcevic2019), links have been made between SM use (particularly appearance-related interactions and upward comparisons) and body dissatisfaction/body image disturbance (Hogue and Mills, Reference Hogue and Mills2019; Holland and Tiggemann, Reference Holland and Tiggemann2016; Meier and Reinecke, Reference Meier and Reinecke2020; Sidani et al., Reference Sidani, Shensa, Hoffman, Hanmer and Primack2016), and exposure to online self-harm material may increase suicidality (Arendt et al., Reference Arendt, Scherr and Romer2019; Memon et al., Reference Memon, Sharma, Mohite and Jain2018).

Finally, SM users may also be exposed to a number of explicit online risks, including those of a criminal nature (El Asam and Katz Reference El Asam and Katz2018), such as fraud, identity-theft, abuse and harassment, grooming, exploitation, radicalisation as well as exposure to age-inappropriate material, reputational damage, and cyber-bullying (Baccarella et al., Reference Baccarella, Wagner, Kietzmann and McCarthy2018; Department for Education, 2019; Sheldon et al., Reference Sheldon, Rauschnabel and Honeycutt2020; Subrahmanyam and Šmahel, Reference Subrahmanyam and Šmahel2011d). However, whilst the online world has broadened opportunities for such exploitation and abuse, the relative risk and frequency of such risks on- and offline should be considered. For example, a meta-analysis found that traditional (i.e. offline) bullying was twice as common as online bullying (Modecki et al., Reference Modecki, Minchin, Harbaugh, Guerra and Runions2014).

Putative mechanisms underlying the proposed benefits of SM use

Whilst the benefits of SM use have typically received much less attention to date, in research as well as the popular media, a number of health benefits have been documented. Inverting some of the proposed harms of SM use, many of these have focused on SM’s potential to facilitate social developmental processes, e.g. through opportunities for identity experimentation, self-expression and social connection, etc., rather than displacement of such opportunities (Subrahmanyam and Šmahel, Reference Subrahmanyam and Šmahel2011a; Subrahmanyam and Šmahel, Reference Subrahmanyam and Šmahel2011c).

Much research has, in particular, focused on the potential for SM use (and the use of digital technologies more broadly) to lead to an accumulation of social resources or cultivation of a sense of connectedness. For example, with respect to ‘channel-centred’ studies focusing on analyses at the level of device and application, Meier and Reinecke (Reference Meier and Reinecke2020) showed in their meta-review that individuals who used SM more intensely reported higher levels of social capital and social support. Relatedly, in a meta-analysis, Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Ainsworth and Baumeister2016) reported a positive association between general social network site use and social capital (r = 0.32, 95% CIs = 0.27, 0.37). Despite this, surprisingly few studies have, to date, extended these findings to directly test a mediating role for such SM-driven accumulation of social capital in mental health and wellbeing (Lomanowska and Guitton, Reference Lomanowska and Guitton2016). There are exceptions, however; for example, in a study of 300 Korean adults, increases in social connectedness were found to mediate the effects of SM use on subjective wellbeing (Ahn and Shin, Reference Ahn and Shin2013).

Despite the relative robustness of findings as to the potential for SM use to result in the accumulation of social capital/social support, for a number of reasons the association is unlikely to be straightforward. First, it is likely underpinned by multiple (potentially interacting) pathways, with the potential for bi-directional causality. For example, whilst feelings of disconnection may drive greater SM use, engagement with SM sites may itself cultivate feelings of connection, such that seemingly contradictory findings may emerge, even within the same dataset (Sheldon et al., Reference Sheldon, Abad and Hinsch2011).

Second, individual-level factors, i.e. attributes of the user, may moderate such associations. For example, whilst the social enhancement (or ‘Rich Get Richer’) theory proposes that individuals who are popular and/or socially resourceful offline build their popularity and social connections further through online interactions, the social compensation (or ‘Poor Get Richer’) theory suggests that individuals who are less popular and/or less socially resourceful offline compensate for this through their online interactions (Zywica and Danowski, Reference Zywica and Danowski2008). The social compensation theory may be particularly relevant to the field of mental health. Thus, there is evidence to suggest that individuals who struggle socially and/or with their mental health, including those who are low in self-esteem (Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe2007), socially anxious (Indian and Grieve, Reference Indian and Grieve2014), socially isolated or excluded (Andrade and Doolin, Reference Andrade and Doolin2016; Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Rezvani and Wiewiora2016), lacking in social/familial support (Keresteš and Štulhofer, Reference Keresteš and Štulhofer2020), or else struggle with social communication (Mazurek, Reference Mazurek2013), may stand to benefit the most from online engagement in terms of improved wellbeing and/or the accumulation of social capital. For these individuals, SM may provide opportunities for connection and support, self-disclosure and identity experimentation that would otherwise be unattainable or else feel unsafe/unmanageable in the offline world (Bonetti et al., Reference Bonetti, Campbell and Gilmore2010).

Third, social capital is a broad, multifaceted construct; for example, as a minimum Putnam (Reference Putnam2001) and others have distinguished between bridging social capital (i.e. ‘weak ties’ between distantly connected people) and bonding social capital (i.e. ‘strong ties’ between close family or friends), and these may differ in their strength and/or patterns of association with SM use (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ainsworth and Baumeister2016). For example, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Holden and Ariati2021) mapped a complex pattern of associations between SM use and wellbeing that was dependent on whether engagement was with ‘strong ties’ or ‘weak ties’, and whether associated engagement was active in nature, or passive. Furthermore, they distinguished between two forms of active SM engagement: (i) active interaction/directive communication, in which the user directly interacts or communicates with others, and (ii) active broadcasting, which they define as ‘actively producing or sharing texts, photos, and videos to an unspecified audience’ (p. 5). Reviewing the evidence, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Holden and Ariati2021) concluded that benefits to mental health are most likely when individuals use SM specifically in order to engage with close associates in an active/interactive manner (Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim and Yang2016), a pattern that they suggested is likely to be mediated by increased social support. Thus, being active online may not suffice; instead, active and purposeful interaction may be optimal for benefits to be accrued.

Examples of active/interactive patterns of engagement that have been linked to social capital and/or wellbeing include the use of SM to meet new people or stay connected with offline contacts (Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe2007), self-disclosure (Gonen and Aharony, Reference Gonen and Aharony2017; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ainsworth and Baumeister2016) and active replying to others (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ainsworth and Baumeister2016). For example, one study had participants increase their posting behaviour on Facebook over the course of a week; relative to a control group that received no instructions, at the end of the study the experimental group reported reductions in loneliness that were driven by a greater sense of connection with friends (große Deters and Mehl, Reference große Deters and Mehl2013). Furthermore, increased perceived online support has been found to mediate effects of active Facebook use on (less) depressed mood and lower levels of loneliness (Frison and Eggermont, Reference Frison and Eggermont2016; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim and Yang2016). One possibility is that such active social engagement facilitates the cultivation of intimacy and building of connectedness (Lomanowska and Guitton, Reference Lomanowska and Guitton2016).

Finally, as a counter to SM’s potential to increase exposure to tangible risks and harms, SM use may also provide opportunities for access to concrete rewards and benefits, including (amongst other things) opportunities for learning (Bruguera et al., Reference Bruguera, Guitert and Romeu2019), financial revenue and career opportunities (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Gu and Whinston2012), access to news (Nielsen and Schrøder, Reference Nielsen and Schrøder2014) and entertainment, peer support and specialist knowledge (Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch and Bartels2016). Relatedly, SM may also play a supportive or curative role for some with pre-existing mental health difficulties, e.g. through mental health initiatives, online support and provision of specialist information (Luxton et al., Reference Luxton, June and Fairall2012; Moorhead et al., Reference Moorhead, Hazlett, Harrison, Carroll, Irwin and Hoving2013; Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch and Bartels2016; Subrahmanyam and Šmahel, Reference Subrahmanyam and Šmahel2011c).

Theoretical underpinnings

The primary theoretical foundations of the conceptualisation are drawn from cognitive behavioural approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and cognitive behavioural theory (Beck, Reference Beck1976). Thus, at the core of the conceptualisation lies a cross-sectional CBT formulation (McDonough et al., Reference McDonough, Duncan, Williams and House1997), on to which additional components are ‘bolted’ or integrated. This decision was driven by our primary aim of making the conceptualisation of maximum practical utility to clinicians working in mental health settings for young people. Thus, CBT has a strong evidence base supporting it, and has demonstrated great flexibility in its application to a wide range of mental health difficulties (Fordham et al., Reference Fordham, Sugavanam, Edwards, Stallard, Howard, Nair, Copsey, Lee, Howick, Hemming and Lamb2021), such that the approach has come to dominate mental health services, including in young people’s services in the UK, as well as further afield. It is our hope that insights and approaches to emerge from the conceptualisation can be integrated easily into existing practices by clinicians currently working face-to-face with young people.

In addition, however, because of our shift away from a causationist approach, which assumes SM to be inherently harmful or beneficial (Orben, 2020b) towards a more contextualist approach, which recognises the crucial significance of interactions between the technology, the individual and their behaviour, and further, emphasises the importance of the function or consequences of use (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Telzer and Prinstein2020), we also drew upon third-wave cognitive behavioural approaches, particularly acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999), which shares such a functional contextualist perspective (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette and Strosahl2016a). This was particularly helpful in guiding our understanding of, and focus on, the function of online behaviours (including approach and avoidance behaviours) over their topography (or form), as well as our integration of the notion of mindful engagement, which is very much in keeping with recent trends to incorporate mindfulness-based concepts and practices within mainstream cognitive behavioural therapies (Baer, Reference Baer, Hayes and Hofmann2018).

In addition to drawing on these foundational approaches to understand core psychological processes, we turned to relevant theoretical literature to inform our understanding of how the individual and the technology interact, as these are largely unexplored within the CBT tradition. Whilst we drew on a large range of theory, we will describe three theories that heavily underpin our conceptualisation, and in particular, shaped our understanding of the three core aspects of the human–technology interaction as we see them: (i) what drives an individual’s engagement with the technology (uses and gratifications theory) (Kircaburun et al., Reference Kircaburun, Alhabash, Tosuntaş and Griffiths2020), (ii) how features of the technology invite or afford different patterns of engagement (the transformation framework) (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b) [see Karahanna et al. (Reference Karahanna, Xu, Xu and Zhang2018) also], as well as (iii) the consequences of this interaction for mental health (the interpersonal connections behaviour framework, and an extension thereof) (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Algoe and Green2018).

In selecting particular theories/frameworks to inform our conceptualisation of the human–technology interaction we drew on our understanding and synthesis of relevant literature, as well as our combined personal experience of theories, hypotheses and frameworks that have proved to be of use in understanding SM use (and the clinical implications thereof) in the young people that we work with. Thus, our decisions as to what to include or exclude were driven primarily by our over-arching aim of making the conceptualisation of maximum practical and clinical utility. Consequently, where possible we also prioritised theory that: (i) took a developmental perspective, focusing specifically on young people’s engagement, or else was highly applicable to this age group, and (ii) was of broad clinical relevance to understanding everyday patterns of use, in contrast, for example, to more specialist theories that have focused solely on pathological patterns of use.

Whilst we do not provide an introduction to CBT or third-wave cognitive behavioural approaches here, as these approaches are likely to be familiar to the common mental health practitioner as well as readers of this journal [see Beck (Reference Beck1995) and Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999), however], we briefly introduce below the main frameworks that informed our understanding of human–computer interactions within the conceptualisation.

Uses and Gratifications theory

The Uses and Gratification theory (U&G) seeks to explain how and why people engage with media (Katz et al., Reference Katz, Blumler and Gurevitch1973), with a greater focus on the human side of the human–technology interaction. Aside from being well-established, with a substantial and wide research base to support it (Lev-On, Reference Lev-On2017), U&G is inherently empowering and of clinical utility, as it posits that users are (primarily) active agents (rather than passive recipients) of information that are motivated to seek out specific media in goal-directed ways in order to satisfy (i.e. gratify) needs and desires. [See LaRose and Eastin (Reference LaRose and Eastin2004), however, for details of how SM habits may also be integrated into a U&G-based model of technology use.]

U&G also proposes that such motivations will vary as a function of inter-individual differences in a range of social and psychological factors (Kircaburun et al., Reference Kircaburun, Alhabash, Tosuntaş and Griffiths2020), making it well suited to an idiographic – i.e. case formulation – approach that highlights personal agency and focuses on the workability of use for the individual. For example, findings from one study of college students suggested that individuals who are more anxious in face-to-face interactions and find offline socialising less rewarding may turn to SM as a ‘compensatory’ strategy, i.e. to connect with others and satisfy social needs (Papacharissi and Rubin, Reference Papacharissi and Rubin2000). In contrast, individuals who are less anxious in offline (face-to-face) interactions and find these more rewarding may be drawn to SM more for non-social purposes, e.g. for entertainment and information-seeking.

Critically, U&G also distinguishes between gratifications sought, meaning the intended purpose(s) for which the media is used (e.g. to connect with others), which we will use interchangeably with the term ‘motivations’, and gratifications obtained, meaning the actual consequences of use (e.g. increased feelings of loneliness and disconnection) (Palmgreen, Reference Palmgreen1984), which we will use interchangeably with the term ‘consequences’. For this reason, the U&G is also well suited to a functional contextual approach that emphasises the consequences of use in determining helpful versus unhelpful patterns of use (see ‘The interpersonal–connections–behaviour framework’ and ‘Types of behaviours and their maintaining role’ sections below). For example, research has shown that self-reported satisfaction with social network site use is high when gratifications obtained exceed gratifications sought, i.e. when SM use effectively satisfies the individual’s needs (Bae, Reference Bae2018).

Although not specific to adolescents or social media, U&G has been used to conceptualise young people’s SM use in a number of studies. For example, Cheung et al. (Reference Cheung, Chiu and Lee2011) showed that amongst adolescents/emerging adults, the primary motivations that predict an intention to use Facebook are social in nature, including a desire for social connectivity, social enhancement and social presence, suggesting that young people turn to SM, predominantly in order to gratify social needs. Seen through a developmental lens, such social motivations for SM use may be particularly pertinent for young people (Ciranka and van den Bos, Reference Ciranka and van den Bos2019) because they map onto key pre-occupations and developmental challenges faced, e.g. those relating to peer acceptance, social connectedness, romantic and sexual exploration, and social identity formation (Ciranka and van den Bos, Reference Ciranka and van den Bos2019; Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Viding, Williams and Blakemore2010; Spies Shapiro and Margolin, Reference Spies Shapiro and Margolin2014). Furthermore, the SM environment may afford opportunities for agency and experimentation in relation to such development needs and desires (Šmahel and Subrahmanyam, 2011e) that are more difficult to access in the offline world because of constraints imposed by parents, college and other systemic factors, as well as perceived barriers relating to the self (Valkenburg and Peter, Reference Valkenburg and Peter2008). However, as noted, the SM environment also brings a number of risks and challenges, such that gratifications sought and gratifications obtained need not be perfectly aligned (Bae, Reference Bae2018).

With respect to associations between motivations and mental health outcomes, existing research in the area is scant (particularly in young people), and has traditionally relied on cross-sectional data that preclude causal inferences (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Holden and Ariati2021). Nonetheless, there is some evidence to suggest that interpersonal/relational motivations for SM use, such as maintaining relationships and a sense of connectedness, may be linked to benefits in terms of reduced psychopathology, including lower levels of depression (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Rosenberg, Egbert, Ploeger, Bernard and King2013) and anxiety (Reichelt, Reference Reichelt2019), as well as improved wellbeing, including higher levels of social support satisfaction (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Rosenberg, Egbert, Ploeger, Bernard and King2013), lower levels of loneliness (Teppers et al., Reference Teppers, Luyckx, Klimstra and Goossens2014), positive social adjustment (Yang and Brown, Reference Yang and Brown2013) and life satisfaction (Adnan and Mavi, Reference Adnan and Mavi2015). It is likely that this is because social benefits are more likely to be accrued when SM use is purposefully engaged with for this purpose.

Such interpersonal/relational motivations may be contrasted to non-social (or even socially avoidant) motivations, several of which have been linked to poorer outcomes. For example, in a single population sample of adults, Perugini and Solano (Reference Perugini and Solano2021) showed that whist the use of SM to maintain relationships and seek information was associated with better well-being, its use to pass the time or for exhibitionism (arguably linked to social comparisons through a heightened awareness of relative status) was associated with poorer wellbeing. Relatedly, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Holden and Ariati2021) distinguished between two classes of SM motivations: (i) enhancement motivations, such as for maintaining existing relationships or seeking entertainment, which function to enhance positive or neutral states, and (ii) compensation motivations, such as meeting new people online, which (may) function to avoid negative affective states and compensate for perceived deficits. Whilst Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Holden and Ariati2021) proposed that such enhancement and compensation motivations may be associated with positive and negative outcomes, respectively, they noted that evidence for this is weak, and further, may reflect socially anxious individuals being driven by compensation motivations, rather than the opposite direction of causality.

The transformation framework

The transformation framework was developed as a comprehensive framework to describe the implications of the SM environment for the establishment and maintenance of peer relationships in adolescence, integrating findings from across multiple disciplines within a clinical and developmental perspective (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b). Whilst a comprehensive review of the literature underpinning the transformation framework lies beyond the remits of this paper, it is important to acknowledge – as the authors do – that the framework draws heavily upon (and synthesises) large bodies of research from within the fields of computer-mediated communication, media psychology, developmental psychology and organisational psychology, some of which we have signposted the reader to in the introduction; see Subrahmanyam and Šmahel (Reference Subrahmanyam and Šmahel2011e), Valkenburg (Reference Valkenburg2017) and Walther (Reference Walther1992, Reference Walther, Braithwaite and Schrodt2015) for example. The transformation framework builds on these ideas, however, by relating these processes to the specific challenges of adolescent development and peer relationships, in both dyadic (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a) and group (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b) contexts [see Karahanna et al., (Reference Karahanna, Xu, Xu and Zhang2018) also].

According to the transformation framework the SM environment represents a unique and novel social context, distinct from face-to-face interactions, with a number of consequences for the nature of cognitive, behavioural and interpersonal processes that it affords (Moreno and Uhls, Reference Moreno and Uhls2019; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b). Thus, whilst online and offline worlds interact, the online world does not merely reflect offline processes, but has the potential to transform it, offering a distinct set of opportunities and risks (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Telzer and Prinstein2020). Specifically, the framework proposes that SM communication is characterised by a number of features, including temporal delays in social exchanges (asynchronicity), the creation of an indefinite trace or history of the communication (permanence), access and exposure to potentially large and/or open audiences (publicness), ease of access and engagement (availability), reduced availability of cues, including facial cues (cue absence), countable social metrics, such as likes and shares (quantifiable), and the potential to share photographic and video material (visualness). Different SM platforms will vary on a continuum with respect to each of these dimensions, and consequently, will afford different patterns of engagement (Karahanna et al., Reference Karahanna, Xu, Xu and Zhang2018; Moreno and Uhls, Reference Moreno and Uhls2019); see Eshraghian and Hafezieh (Reference Eshraghian and Hafezieh2017) for a review of the application of affordance theory to SM research. For example, one of the key appeals of Snapchat is that messages are only available for a defined/brief period of time (low permanence). Different tools or setting options within a given platform may also vary with respect to these feature dimensions. For example, Snapchat has now evolved to include longer-lasting and archival functionalities, including the ‘Snapchat Story’ feature, with putative impacts on the nature of user engagement (Cardell et al., Reference Cardell, Douglas, Maguire, Avieson and Giles2017).

Critically, the framework proposes that as a result of these characteristics, social interactions are transformed when they occur online, as noted, both with respect to dyadic and group communication. Specifically, they commonly: (i) change the frequency or immediacy of interactions (e.g. facilitation of high-speed messaging between individuals in a friendship group), (ii) amplify experiences and demands (e.g. intensification of an online dispute because of its public nature and the sheer volume of potential content), (iii) qualitatively change the nature of the experience (e.g. bullying may be perceived as harsher because of the anonymity of the perpetrator), (iv) facilitate compensatory behaviours, i.e. behaviours that may be more challenging in the offline world (e.g. social interactions may feel safer than offline interactions because of the asynchronicity in communication), and (v) provide opportunities for completely new behaviours and experiences (e.g. connection to specialist interest groups with people from far afield) (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b).

The transformation framework does not imply that these effects are inherently positive or negative, but instead bring a range of potential risks and benefits. Nonetheless, and critical here with respect to impacts on mental health, Nesi and colleagues propose that, for some, a number of problematic interpersonal – or ‘depressogenic’ – processes may be amplified or increased in frequency within the context of online interactions (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b). These include: social comparisons, co-rumination [defined as an excessive discussion of/rumination on problems and stressors with others (Rose, Reference Rose2002)], reassurance-seeking and feedback-seeking (Nesi and Prinstein, Reference Nesi and Prinstein2015). To take one example, (judgemental) social comparisons (and relatedly, negative self-image) may be facilitated online by the visualness, publicness, quantifiableness and availability of the SM environment, which essentially provides a highly detailed and easily accessible window onto others’ lives (Fardouly et al., Reference Fardouly, Pinkus and Vartanian2017; Marengo et al., Reference Marengo, Longobardi, Fabris and Settanni2018). Furthermore, the asynchronicity of the communication may also encourage heavy editing/engineering of photographs and self-representations (Kasch, Reference Kasch2013), such that the impression garnered is likely to be highly curated and idealised. Adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to such processes by virtue of their heightened sensitivity to peer influence (Ciranka and van den Bos, Reference Ciranka and van den Bos2019) and peer rejection (Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Viding, Williams and Blakemore2010), as well as the fluid/developing nature of their identity (Spies Shapiro and Margolin, Reference Spies Shapiro and Margolin2014).

Conversely, several of the SM features explored may serve to afford more positive interactions and behaviours – both compensatory and novel (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b). For example, the cue absence and asynchronicity of SM platforms may reduce the intensity of social interactions, and allow for communication to be slowed down, rehearsed and reflected upon (Bonetti et al., Reference Bonetti, Campbell and Gilmore2010; Harman et al., Reference Harman, Hansen, Cochran and Lindsey2005; Michikyan et al., Reference Michikyan, Subrahmanyam and Dennis2014; Valkenburg and Peter, Reference Valkenburg and Peter2008). This may be of particular benefit to individuals who struggle in more traditional face-to-face social settings.

As another example of how design features may facilitate positive behaviour and mental health, whilst the permanence, availability and quantifiable nature of many platforms may facilitate the spread and uptake of problematic behaviours such as self-harm (George, Reference George2019), it also has the potential to amplify prosocial interactions (Erreygers et al., Reference Erreygers, Vandebosch, Vranjes, Baillien and De Witte2019; Tsvetkova and Macy, Reference Tsvetkova and Macy2015). Indeed, there is evidence that with respect to online interactions amongst adolescents, prosocial behaviours may in fact be more common than antisocial ones (Erreygers et al., Reference Erreygers, Vandebosch, Vranjes, Baillien and De Witte2017; Lister, Reference Lister2007). This is crucial as we know that heightened sensitivity to peer influence and peer rejection during adolescence is true of prosocial as well as antisocial behaviour (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Ahmed and Blakemore2020). Thus, the very same features of online communication that carry risks also open up opportunities and potential benefits (Hollis et al., Reference Hollis, Livingstone and Sonuga-Barke2020; Livingstone and Helsper, Reference Livingstone and Helsper2010).

Extension of the transformation framework

In addition to the core features of SM platforms proposed by the transformation framework (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b), which we have summarised above, we would suggest that SM platforms typically exhibit a number of additional design features, the primary function of which is to compete for users’ attention and maximise engagement (Alter, Reference Alter2017; Hill, Reference Hill2018; Lewis, Reference Lewis2017; Zuboff, Reference Zuboff2015), with potential implications for – and impacts on – the user’s ‘response state’, i.e. their cognitive, emotional and excitative state during engagement (Valkenburg and Peter, Reference Valkenburg and Peter2013), the nature of their engagement (i.e. online behaviour), and potentially, their mental health. These additional features include: (i) filtering algorithms, which selectively propagate information that is trending, (ii) intermittent status updates and notifications (Bosker, Reference Bosker2016; Lindström et al., Reference Lindström, Bellander, Schultner, Chang, Tobler and Amodio2021), and (iii) infinite scrolling and automatic play/replay content features (Noë et al., Reference Noë, Turner, Linden, Allen, Winkens and Whitaker2019).

In terms of the implications of these features for the response state of the SM user and their pattern of engagement, the nature of (i) filtering algorithms means that users are more likely to be exposed to information (e.g. posts and news stories) that they have previously accessed or else are trending within their network (Ciampaglia et al., Reference Ciampaglia, Nematzadeh, Menczer and Flammini2018), which by its very nature is likely to elicit strong emotional responses and high levels of arousal/excitation (amplifying and sensationalising). Thus, even if SM algorithms are not purposefully designed to amplify the emotional or excitative state of its users, the reality is that because emotional material increases attentional capture and user engagement (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Gantman and Van Bavel2020; Kozyreva et al., Reference Kozyreva, Lewandowsky and Hertwig2020; Tufekci, Reference Tufekci2013), there will be an algorithmic pull towards material that is controversial, extreme, polarised (Van Bavel et al., Reference Van Bavel, Rathje, Harris, Robertson and Sternisko2021), divisive and/or likely to elicit strong moral emotions such as outrage (Crockett, Reference Crockett2017; Goldenberg and Gross, Reference Goldenberg and Gross2020). For example, messages that elicit fear, disgust and surprise or include ‘moral-emotional’ words are more likely to spread (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Wills, Jost, Tucker, Van Bavel and Fiske2017; Vosoughi et al., Reference Vosoughi, Mohsenvand and Roy2017). Furthermore, immoral acts are more likely to be encountered online and elicit stronger moral outrage than similar acts learnt about in person or through other more traditional forms of media (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Wills, Jost, Tucker, Van Bavel and Fiske2017).

With respect to (ii) intermittent status updates and notifications (Bosker, Reference Bosker2016; Lindström et al., Reference Lindström, Bellander, Schultner, Chang, Tobler and Amodio2021), because of the uncertainty and unpredictability of social interactions, these will typically follow a variable-ratio reward schedule that will reinforce levels of engagement, i.e. increase usage, through basic operant conditioning processes (reinforcing). Finally, with respect to (iii) infinite scrolling, and relatedly, automatic play/replay content (Noë et al., Reference Noë, Turner, Linden, Allen, Winkens and Whitaker2019), these features maximise attentional capture and allow users to endlessly absorb material with minimal decision points and stopping cues, and hence minimal cognitive engagement with the decision process (absorbing) (LaRose, Reference LaRose2010; Noë et al., Reference Noë, Turner, Linden, Allen, Winkens and Whitaker2019).

In terms of the implications of these for mental health, the reinforcing and absorbing nature of the experience may increase the likelihood of automatic/habitual patterns of engagement (Eyal and Hoover, Reference Eyal and Hoover2014), which are potentially linked to negative mental health outcomes through a number of casual pathways. Whilst these processes (and the links between them) are explained in greater depth in the ‘Consequences and feedback loops’ section, it may suffice to note at this point, that when attention and behaviour is strongly captured by the media itself (reinforcing and absorbing), because of the limited capacity of attentional resources, attention to other cues beyond the screen (both internal and external) will be diminished, including those that may signal a potential benefit to stopping engagement, e.g. feelings of anger or fear triggered by an online interaction. Engagement thus becomes automatic or habitual, conditions under which it is easy to see how problematic patterns of use may emerge (Aarts et al., Reference Aarts, Verplanken and Knippenberg1998; Bae, Reference Bae2018; LaRose, Reference LaRose2010; LaRose et al., Reference LaRose, Lin and Eastin2003; Verplanken et al., Reference Verplanken, Aarts and Van Knippenberg1997).

With respect to the amplifying and sensationalising nature of the experience, this may feed negative emotions and exacerbate cognitive distortions/information processing biases, such as negativity biases, which lay at the core of many mental health difficulties and feed unhelpful cycles of thoughts, feelings/sensations and behaviours (Abramson et al., Reference Abramson, Metalsky and Alloy1989; Riskind, Reference Riskind1997). Again, whilst we explore these processes in greater depth in the ‘Information processing biases’ section, as a simple example, exposure to trending material that is highly emotive and triggering, e.g. graphic details of violent crime, may serve to confirm the beliefs of an anxious individual as to the dangerous nature of the world, thereby reinforcing negativity biases and increasing perceived threat (see Vignette 1 for example).

Sonja was a young lady in her late teens who was highly anxious, withdrawn and avoidant [maladaptive core CBT cycle]. Over the course of therapy it became clear that some of her concerns about leaving the house related to an unrealistic appraisal of the risk of being murdered on the streets of her city, which she estimated as being 10% likely over the course of any given year [biased processing]. Further exploration of this belief and its origins indicated that it was perpetuated, in part, by her SM feed, which often featured gruesome and sensationalist stories that would elicit strong reactions and many shares within her network [biased processing, fed by amplifying and sensationalising features of the technology]. In response to this, we spent one of our sessions exploring the role of SM and her online experience in driving some of these beliefs and underlying cognitive distortions [psycho-education/SM literacy training], e.g. magnification and catastrophisation, and together identified alternative, more reliable sources of online information to help Sonja assess the genuine level of risk posed [intentional/purposeful engagement supporting relatively unbiased processing]. Further, in later sessions we explored how Sonja could meet with friends she’d initially met online in face-to-face contexts in a way that was safe, but also manageable given her current level of anxiety [social approach behaviours supported by intentional/purposeful engagement]. In the process she was able to gradually overcome her cycle of avoidance [cultivation of social approach behaviours, resulting in satisfaction of core needs relating to belonging and acceptance, and positive reinforcement], and test out some of her beliefs about how others would perceive and respond to her in person [amelioration of information processing biases].

These reinforcing, absorbing, amplifying and sensationalising processes are also likely to interact. Thus, in their Differential Susceptibility to Media Effects Model (DSMM), Valkenburg and Peter (Reference Valkenburg and Peter2013) propose that the effects of media (including impacts on behaviour and emotion, and by implication mental health) may be most pronounced and long-lasting when ‘cognitive, emotional and excitatory sliders, are high’ (p. 229). Such a state might be expected, we would argue, when the user is highly absorbed and engaged in the technology, and further, consuming and/or interacting (in a relatively uncritical way) with material that is highly emotionally evocative. Once again, there may be an algorithmic pull towards such states, although this is likely to vary across platforms and platform utilities.

The interpersonal–connections–behaviour framework

The interpersonal–connections–behaviour framework proposes a simple but powerful idea: that SM use is (in large part) beneficial or harmful to the individual to the extent that it promotes or frustrates core desires for acceptance and belonging, respectively (social gratifications obtained) (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Algoe and Green2018) [see Verduyn et al. (Reference Verduyn, Ybarra, Résibois, Jonides and Kross2017) also]. Whilst the framework was not designed specifically with adolescence in mind, we would argue that it is particularly relevant to this age group. Thus, acceptance and belonging and avoidance of rejection act as powerful motivators for behaviour during adolescence and are linked to key developmental challenges (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Lieberman and Williams2003; Tomova et al., Reference Tomova, Andrews and Blakemore2021). Furthermore, as noted, social motivations for SM use (gratifications sought) appear to be particularly important in driving this age group’s intention to engage with the technology (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Chiu and Lee2011).

In their review of evidence supporting the interpersonal–connections–behaviour framework, Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Algoe and Green2018) suggested that negative outcomes are more likely when SM engagement is superficial and characterised by interaction patterns that are unlikely to cultivate genuine intimacy and long-term satisfaction of core social needs, e.g. ‘social snacking’ (p. 33), and/or patterns of use that are likely to cultivate feelings of disconnection, e.g. ‘lurking on stranger’s profiles’ (p. 33) (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Algoe and Green2018). Thus, they draw on a body of literature that highlights associations between passive patterns of use, e.g. scrolling, browsing and judgemental social comparisons, and poorer mental health/wellbeing. Conversely, Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Algoe and Green2018) highlight findings that link more active/interactive patterns of engagement, e.g. self-disclosure, online posting and direct exchanges with others, to better mental health/wellbeing, putatively through the accumulation of social capital and the cultivation of a greater sense of connectedness. We do not review these findings again here, but instead direct the reader back to the ‘Social media use and mental health’ section.

Integration of core theory

Integrating the evidence base reviewed and core theories/theoretical frameworks discussed within a developmental perspective, we propose that SM engagement may be particularly beneficial or helpful to the adolescent where use results in increased satisfaction of core needs (gratifications obtained), particularly those relating to developmentally pertinent needs of acceptance and belonging. Furthermore, we propose that such satisfaction of needs is most likely to occur when: (i) the individual’s motivations for use (gratifications sought) are primarily for social enhancement purposes, with a focus on cultivating and maintaining deep and genuine connections, (ii) the nature of the user’s online engagement is aligned with such enhancement motivations (e.g. engagement is active/interactive and non-judgemental), and relatedly, (iii) platforms used by the individual afford/support such patterns of engagement. Finally, SM may also be beneficial to mental health where it supports an amelioration of cognitive biases, e.g. negativity biases.

In contrast, SM engagement may be particularly harmful or unhelpful to the adolescent where use results in decreased satisfaction of core needs (gratifications obtained), particularly those relating to developmentally pertinent needs of acceptance and belonging, (e.g. increased feelings of loneliness or disconnection). Furthermore, we propose that this may be most likely when: (i) the individual’s motivations for use are (at least in part) social in nature (gratifications sought), but (ii) satisfaction of these needs is not supported by the individual’s actual online engagement (e.g. engagement is passive and judgemental, characterised in large part by social comparisons), and relatedly, (iii) the platforms which the individual uses do not afford helpful patterns of engagement, or else actively afford unhelpful patterns of engagement. SM engagement may also be harmful or unhelpful to the adolescent where the individual’s motivations for use (gratifications sought) directly conflict with satisfaction of core needs relating to belonging and acceptance, for example where SM use is (predominantly and persistently) motivated by compensatory motivations relating to escape or avoidance. Finally, SM may also be harmful where it feeds into existing cognitive biases that perpetuate unhelpful patterns of thoughts and feelings.

The conceptualisation

Overview

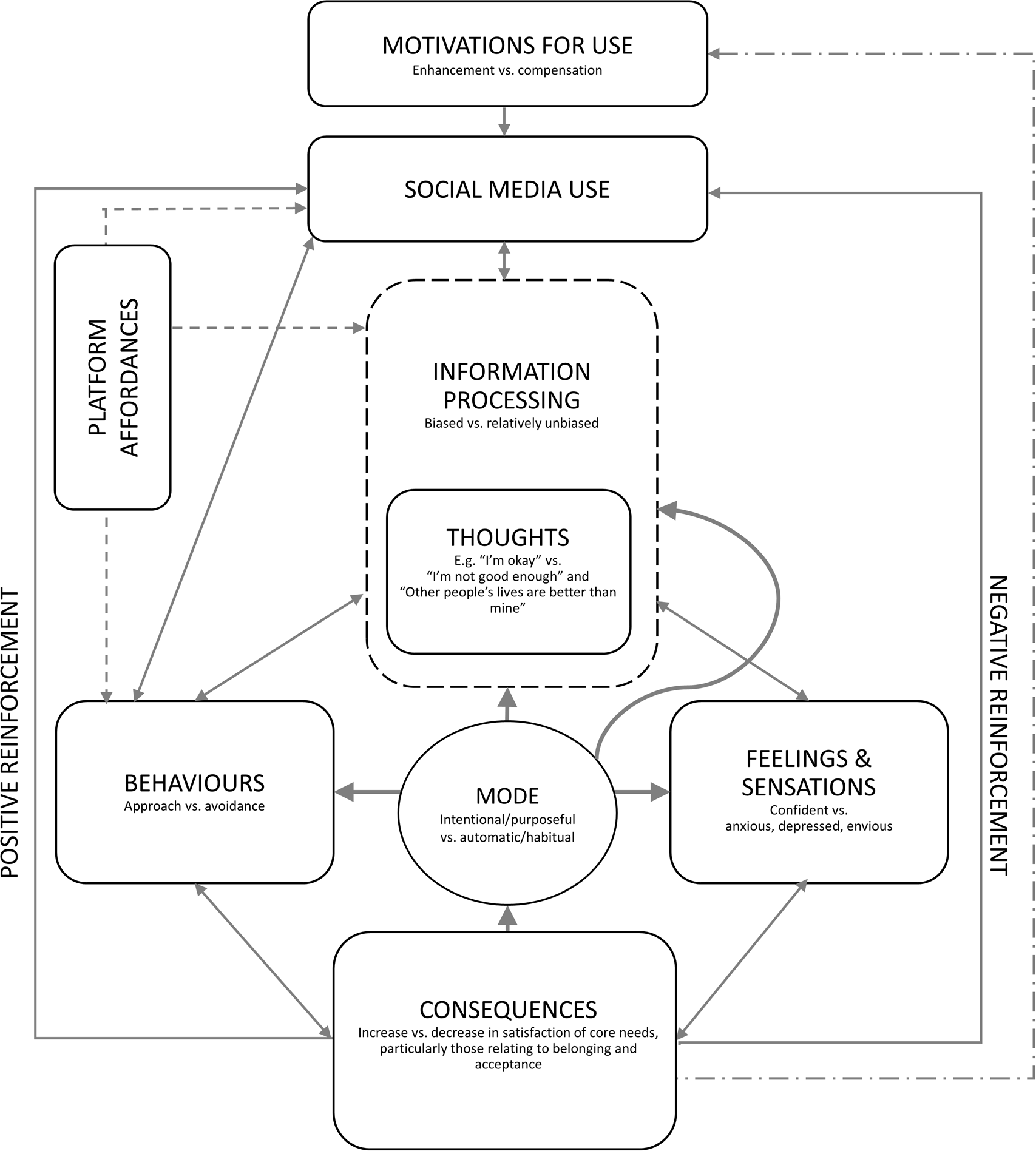

As noted, at the core of the conceptualisation lies a cross-sectional CBT cycle (McDonough et al., Reference McDonough, Duncan, Williams and House1997), which typically includes triggers, thoughts, feelings, sensations and behaviours (Fig. 1). For simplicity, feelings and sensations are collapsed, and the initial trigger/input to the model is defined as SM use. Other additions include: (i) a box to represent motivations for use, (ii) a box to represent information processing (David et al., Reference David, Miclea and Opre2004), which may be biased or relatively unbiased, and filters incoming (online and offline) information; (iii) a box to represent features and associated affordances of SM platforms (platform affordances), which may influence engagement with SM and how information is processed; (iv) a box to represent consequences or outputs of the model (i.e. gratifications obtained), with (v) feedback loops connecting consequences to motivations/SM use (as well as the user’s mode of engagement), and finally, (vi) a box to represent the mode of SM engagement, i.e. whether engagement is intentional/purposeful, or automatic/habitual.

Figure 1. The conceptualisation / model.

Considering unhelpful patterns of SM use first, the individual has various motivations for engaging with the technology, which are underpinned by needs, including social needs, that they hope to gratify. Incoming information derived from these online interactions (social media use) is filtered by information processing biases (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979; Wells, Reference Wells1997), which drive and perpetuate unhealthy cycles of thoughts, feelings and behaviours, and ultimately, a number of negative consequences. To take a hypothetical – although relatively typical – example, consider a young SM user (let’s call her Yma) who goes online in order to connect with her peers (motivation) and reads a friend’s online post about a recent holiday. When filtered through a negativity bias, this might elicit negative automatic thoughts such as ‘other people’s lives are better than mine’ or ‘I’m not good enough’, driving a dip in mood, and as a result, a compulsion to socially withdraw and monitor others’ posts for confirmation/disconfirmation of this belief (avoidance behaviour) (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979; Wells, Reference Wells1997). Whilst this cycle is reminiscent of offline interactions, it may be exacerbated online by the features and associated affordances of the SM platform, e.g. the fact that the material is highly visual, constantly accessible, and linked to social metrics such as likes and shares (availability, visualness, quantifiable). Furthermore, the reinforcing and absorbing nature of the experience, which is intended to hijack attention and maximise usage, may activate an automatic/habitual mode of engagement, which reduces Yma’s capacity to effectively self-monitor and critically evaluate presented material (e.g. recognise that the friend’s profile is likely to be heavily curated). As a result, cognition takes a ‘short-cut’ or uses a heuristic, information processing is biased, and the whole cycle is perpetuated.

Conversely, healthy or non-problematic cycles of thoughts, feelings and behaviours are enabled by relatively veridical information processing. Returning to our hypothetical example, imagine that Yma reads the same holiday post when she is in a very different state of mind, and is able to process the information in a relatively unbiased, and more critical, fashion, able to recognise, for example, the heavily curated nature of her friend’s profile. Relatively free of a negativity bias, thoughts triggered in this very different context might be neutral, or perhaps even linked to a positive memory of a similar childhood holiday with a family friend, such that a feeling of warmth or gratitude is elicited. This, in turn, drives Yma to reach out to the childhood friend (motivation), searching for them online and sending them a personalised message to invite them to join their network (approach behaviour). In this context, the affordances of SM, e.g. its availableness and publicness, will have facilitated this positive cycle, making it easier for Yma to locate and connect with her childhood friend. However, this requires intentional/purposeful engagement with the technology (mode), in the absence of which the pull will be towards a passive scrolling of online material, which has itself been linked to higher levels of (judgemental) social comparisons and associated feelings of envy (Appel et al., Reference Appel, Gerlach and Crusius2016; Krasnova et al., Reference Krasnova, Widjaja, Buxmann, Wenninger and Benbasat2015; Tandoc et al., Reference Tandoc, Ferrucci and Duffy2015; Verduyn et al., Reference Verduyn, Lee, Park, Shablack, Orvell, Bayer, Ybarra, Jonides and Kross2015; Verduyn et al., Reference Verduyn, Ybarra, Résibois, Jonides and Kross2017).

As a result of this cascade of thoughts, feelings/sensations and behaviours, a set of consequences follow, the nature of which ultimately determine whether, irrespective of the motivation for engagement, the original SM behaviour engaged in proves to be helpful or unhelpful. Thus, within the conceptualisation, aside from their impact on information processing biases (and associated exacerbation/amelioration of problematic patterns of thoughts, feelings, sensations and behaviours), patterns of SM use are associated with positive and negative mental health outcomes primarily as a function of their capacity to promote or frustrate (respectively) satisfaction of core needs for acceptance and belonging.