INTRODUCTION

This article analyses changes in the organization of labour during the first two colonial centuries, focusing on the role played by the different colonial authorities in this process and its consequences. Our starting point is the reforms carried out by Viceroy Francisco de Toledo during the 1570s, while we also consider past labour organization. This allows us to cast light on the role the colonial authorities played in labour relations and how that role changed during Toledo’s rule. Engaging with the broader framework of this special issue, we suggest that those colonial authorities were mobilizers and allocators of labour; only occasionally were they direct employers.

In this article, we understand Charcas – a term with multiple meanings – in an operative way sensu Barnadas:Footnote 1 a historically cohesive territory, the central force of which was Potosí. Between 1542 and 1776, Charcas was included in the Peruvian Viceroyalty and, after 1561, it was the centre of the jurisdiction of the Royal Audience of Charcas (supreme court of justice). The geographical scope of our study extends from Lake Titicaca in the north to the southern border of present-day Bolivia, excluding those indigenous territories on the eastern lowlands that were not under external control at that time (Figure 1). This complex territory, inhabited by a range of ethnic groups, was conquered by the Incas during the fifteenth century and during the 1530s by the Spanish. The relationship those groups had with the Incas, and later on with the Spanish, varied from war to alliance, and the first colonial decades were especially conflictive.

Figure 1 Charcas during the seventeenth century.

Although mining activities began with the Spanish conquest, the exploitation of the most important centre, Potosí, did not get underway until 1545, in the context of the civil war among the conquerors. In 1548, the Crown managed to put an end to the rebellion, but the power of the local Spanish lords did not diminish until the arrival of the fifth Viceroy of Peru, Francisco de Toledo (1569–1581). Before Toledo, the Crown had granted privileges to particular Spaniards who had actually carried out the conquest. They were given rights (encomienda) to obtain tributes from the indigenous peoples, paid in the form of goods, silver, gold, labour, or personal services.

In this article, we focus especially on the changes made to the indigenous tributary system and on the forced mine labour, known as mita, which Toledo introduced for the Potosí silver mines and mills. Here, we want to stress one of the changes introduced by Toledo, namely dividing indigenous obligations into two: all indigenous tributaries (men between eighteen and fifty years’ old) had to pay a monetary tribute to the Crown, and a proportion of those men had to work for Spaniards, mainly in mining activities, for a specific period of time (mita). The mita was a state-coordinated form of draft labour that influenced the lives of the majority of the indigenous population in Charcas, as we will see. These changes were central to the evolution of labour relations in the following century.

The seventeenth century saw a massive process of migration of indigenous peoples, caused by the changes mentioned above, since they were forced to obtain money to pay the tributes or to pay for a replacement for the mita, or alternatively responded by running away from their ethnic authorities or colonial obligations. Despite migration posing complications concerning the payment of tributes, as well as concerning the observance of the mining mita system, the colonial authorities did not respond. We argue that an important causal factor in this official reticence was the fact that this massive indigenous migration process favoured the private acquisition of labour by the Spanish owners of other mines and haciendas, as well as of other productive activities. Hence, we examine the changes carried out to mine labour by the Spanish colonial polity and its consequences not only for mining, but also for all labour relations in the southern colonial Andes.

We have analysed a range of concepts, including tribute, payment, and free labour, within the framework of the taxonomy of labour relations developed by the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations (Collaboratory). In our final section, we will reflect upon the changes in labour relations in the light of this taxonomy.

INITIAL ORGANIZATION OF COLONIAL LABOUR

This section focuses on those aspects of the colonial labour organization that were reformed by Viceroy Toledo in the 1570s, and that, later on, constituted a model that continued to operate throughout the seventeenth century. The early colonial organization of labour in the Peruvian Viceroyalty was based partly on two important defining aspects: first, indirect rule, and second pre-existent, although substantively changed, forms of labour organization. As we will discuss in the final section, indirect rule implied a combination of two different types of labour relations. The first was between the beneficiary of the indigenous obligations (which could be an individual Spaniard, the Crown, or the church) and the native authorities responsible for those obligations that their communities had to fulfil. The second type was between the local native authorities and their people. This was the organizational key: indigenous people went to work in the mines or on the coca lands, paid their tributes in silver, or did whatever they had to, because of the relationship they had with the native authorities (Spanish: caciques)Footnote 2 based on different types of reciprocity.

The Spanish took advantage of the Inca tributary system. According to Murra,Footnote 3 before the conquest, all communities had to provide male and female labour to periodically perform a range of different tasks; they had to produce goods for the Inca authorities or for their own local authorities, and goods – offerings – for the gods. However, men from a specific group, the yana, were in a different position, since they were separated from their communities and native authorities and were placed in the service of the Incas themselves, or in the service of other authorities.Footnote 4 Their children inherited their status, and they were not obliged to perform the same periodic tasks that other natives were required to. This pre-Hispanic distinction between natives belonging to a community and the yanas persisted after the conquest, although in a colonial system.

What specific mechanisms were used by the Spanish to recruit native labour for their enterprises during the first few decades of the conquest? In general terms, indigenous slavery was forbidden soon after the demographic collapse in the Caribbean islands. The most widespread form of labour recruitment, especially in the Peruvian Viceroyalty, was the encomienda, legitimized by the Crown. This royally sanctioned institution entailed some of those Spaniards taking part in the conquest acquiring rights to receive tributes from a native authority and from any people subjected to it. In return, the beneficiary had to promote their welfare and guarantee that the indigenous people would embrace Christianity. The beneficiary was also obliged to contribute to the military defence of his jurisdiction of residence.Footnote 5 Indigenous people were obliged to pay tributes in the form of goods, silver, gold, labour, or personal services. Right from the beginning, then, the Spanish could access the labour, and sometimes the capital, needed to develop agricultural, mining, and ranching enterprises.Footnote 6 Most encomiendas benefited individuals, though a few were under the direct control of the Crown.

The second form of labour recruitment, which was present only in the Peruvian Viceroyalty, was the yanaconazgo. Although the yana population has its origins in the pre-Hispanic period, its significance changed completely during colonial times. Since the earliest decades of the conquest, they were a kind of servant and were not present in other regions – such as Mexico – at least not in the same number.Footnote 7 There were different types of yanaconas, working for individuals, for the Crown, or for the church, although the largest group were those attached to the land, working on Spanish haciendas. From 1566, they were obliged to pay tribute in cash to the Crown, but usually they did not pay at all.

We want to stress two aspects of the organization of labour in this period that are important for our analysis. First, the encomienda implied a community and its native authority, which mediated the community’s relationship with the encomendero, being a Spanish individual or the Crown.Footnote 8 They preserved their land and their internal socio-political organization. The native authorities collected and paid their tributes to the encomendero in the form of silver and goods. Indigenous people included in the encomienda were also obliged to perform some public and private tasks, coordinated by their own native authority (such as carrying post, taking care of the upkeep of roads, building churches, and providing food for priests). After the extinction of their encomiendas, these indigenous people became royal tributaries and some of them were conscripted for the mita. Second, the yanaconas were separated from their communities; they had no land, nor did they recognize a native authority.Footnote 9 They had to work for Spanish individuals, in mines, houses, on haciendas, or for the church. In most cases, they served the Spanish, without any mediation, but there were also yanaconas working for themselves, especially in urban contexts. They were not obliged to take part in the mita, nor bound by other collective obligations. Until 1566, the yanaconas did not have to pay tribute to the Crown.

These two forms of labour organization were the most important in terms of numbers involved, and because they were official. Moreover, many of those who belonged to an encomienda were forced to fulfil colonial obligations only part of their time, depending on the community, the tasks they had to undertake, and their status. Not all indigenous individuals were necessarily included in those forms, and in a way they were “free”; there were some who could work for themselves, the most important of them being traders and artisans, who were inside the colonial economy but relatively independent.

MINING AND LABOUR IN THE ANDES: VICEROY TOLEDO

From the mid-sixteenth century, and almost until the present, the Americas produced most of the world’s silver and gold. Between 1550 and 1800, Mexico and South America accounted for over eighty per cent of the world’s silver production, and over seventy per cent of all gold production.Footnote 10 During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Viceroyalty of Peru was notable for its mining production, while the Viceroyalty of New Spain was the most important mining region during the eighteenth century. One feature that distinguished these two places was the centrality of a unique mine in Peru: Potosí. During its heyday, it accounted for over ninety per cent of the Viceroyalty’s production. Its silver production was so important that, even when in decline, it continued to dominate global Spanish-American production.Footnote 11 In this section, we focus on the main aspects of the mine labour system at Potosí, including both free and coercive labour.Footnote 12 We suggest that, directly or indirectly, mining was the activity that organized the colonial labour world, not only in Charcas, but throughout the Viceroyalty of Peru.

In the context of a Crown besieged by debt, the extraction of precious metals was a royal priority. Within this context, towards the end of the sixteenth century Viceroy Toledo introduced a range of reform measures. Firstly, these reforms aimed to increase Peruvian silver production, which had started to decline in the 1560s because of the extinction of the high-grade ores. To achieve this, silver was amalgamated with mercury and a system of lakes built in order to supply the silver refineries (ingenios).Footnote 13 Further, a compulsory labour system, the mita, was introduced for Potosí silver production.Footnote 14

Secondly, the reforms tried to increase control over the indigenous population, with varying degrees of success. This was effected through the so-called process of reducción, an attempt to concentrate in colonial towns the indigenous population living in dispersed settlements. This process affected more than one million people, and it aimed to make more effective the organization and fulfilment of colonial obligations, being both tribute and mita, as well as to improve evangelization and to impose a cultural model through European urban life patterns.

Thirdly, Viceroy Toledo massively monetized the tributary system. This system calculated the tribute per capita for the male indigenous tributary population in each repartimiento de indios (fiscal and administrative unit), but responsibility for payment lay with the caciques.Footnote 15 This monetized tribute obliged indigenous people, one way or another, to participate in commodified relationships, offering their products in the market or their labour in exchange for money. The labour relationships, even those mediated by money, could be both voluntary and coercive.Footnote 16 In order to achieve these three main goals, Viceroy Toledo developed a fourth measure: a general visita, or inspection of the Viceroyalty, which recorded the number of individuals and their resources. The inspection played a key role in the reconfiguration process and in the imposition of a new order that involved the mita system, the payment of tributes, and the relocation of the indigenous population to new rural towns.

The characteristics of Potosí’s mine labour system have been widely studied, so we will merely summarize its central elements here. The Potosí mita was a state-coordinated form of draft labour, systematically organized since 1573. Its major objective was to reorganize mine labour according to royal needs and the increasing political power of the state. Toledo’s mining mita had pre-Hispanic precedents: the system was inspired by how the Incas had organized labour. Toledo’s mining mita also had colonial antecedents taken from the first period of Potosí silver production, then dominated by native technology known as the huayra stage.Footnote 17

The mita system established the forced migration to Potosí of a percentage of the male indigenous tributaries, mitayos, and their families for one year from the sixteen highland corregimientos (provinces) in the region between Cuzco and the southern border of present-day Bolivia (Figure 1). In 1575, Toledo determined the percentages of mitayos each region should send annually: between thirteen per cent and seventeen per cent of their tributaries. Different viceroys established the annual total, “mita gruesa”, which varied only during the initial years of the system: between 1573 and 1575, the number of mitayos varied from about 9,500 to around 11,000; but from 1578 to the 1680s, it was fixed at around 14,000. The mita labour system divided the annual contingent into thirds: one-third were obliged to work weekly, while the other two-thirds rested, although only theoretically.Footnote 18 Mitayos were obliged to work weekly for a limited number of Spanish owners of mines and mills.Footnote 19 In 1575, Viceroy Toledo established the mita “capitanías” to organize and ensure mitayo labour in Potosí. This institution appointed native leaders, who were responsible for the mobility and presence of forced mine labourers. In the beginning, this was a position of great power and prestige, but by the seventeenth century it had become a heavy and difficult burden to bear.

The polity fixed the wages of forced labourers at a rate below those paid to “free” labourers. In theory, wages were paid in money and were insufficient to ensure the reproduction of labour power. In addition to wages, mitayos also had resources from their communities of origin, which thereby subsidized colonial mining production.Footnote 20 Mitayos women also contributed to their household economy by working in the urban markets.Footnote 21 Apart from paying their tributes (almost ninety per cent of their income), mitayos were also obliged to contribute part of their wages to pay the salaries of royal officials, mita captains, and hospitals.Footnote 22 Finally, they needed money to pay for their individual and family livelihood, such as food, clothes, housing, and candles for the mines. Clearly, they had no choice but to look for other job opportunities as “free” labourers during their period of “rest”.Footnote 23 This guaranteed mine owners a permanent supply of “free” labour.Footnote 24 Assadourian has estimated that at the beginning of the seventeenth century – during the mining boom in Potosí – seventy per cent of the labour force was hired and thirty per cent was forced.Footnote 25 Hired labour was important in terms of numbers, particularly in specialized and better-paid tasks.Footnote 26 The mita could be fulfilled in person, but substitution (conmutación) was also permitted. This meant that it was possible to pay a fixed sum of money for each absent mitayo. With that money, termed “silver Indian”, it was possible to hire and pay a labourer. However, the money paid in compensation was not always used to hire a replacement; often it remained in the pockets of the Spanish beneficiaries of the mita (mine owners and mill owners).

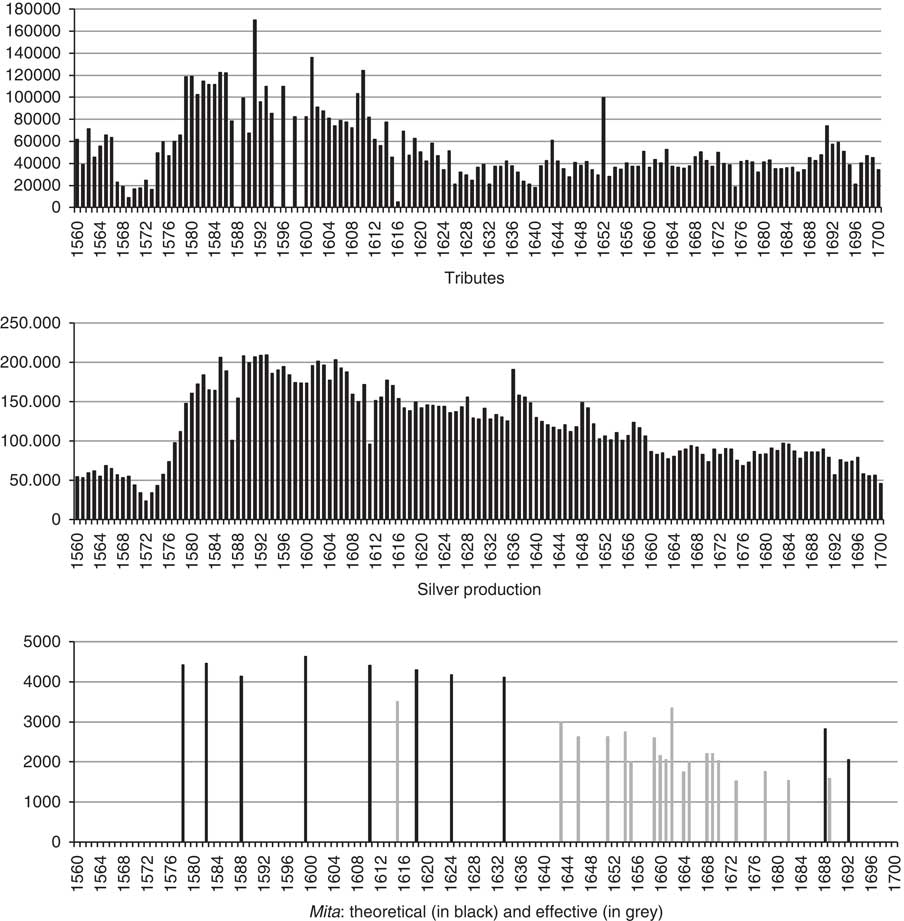

There are two different ways of evaluating the numbers covered by the mita. On the one hand, we have the official list of annual mitayos, that is the estimated number of mitayos forced to work in the mines and mills of Potosí; on the other hand, we can also consider the effective number of mitayos who really went there and worked. At around 14,000 per annum the estimated number was very stable until the end of the seventeenth century, but the effective numbers – information not easily found and not systematicFootnote 27 – corresponded closely to silver production: they fell throughout the century. It was not until the government of Viceroy La Palata in the late 1680s that the theoretical and effective numbers tended to coincide (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Tributes, silver production, and the mita, Potosí, 1560–1700. Sources: Tributes (in pesos) and silver production (in kilos), TePaske (http://www.insidemydesk.com/hdd.html); mita (number of mitayos), Cole, The Potosí Mita, pp. 41, 72; Tandeter, Coacción y mercado, pp. 39–48.

Only Potosí and a few other mining centres benefited from the mita, which means that, in almost all other mining camps, hired labour prevailed. These kinds of labourers quickly increased in number from the last quarter of the sixteenth century onwards, partly because of growing demand for specialists in mercury amalgam technology and partly because of the end of the encomienda system.Footnote 28 Hired and paid labour, however, did not mean a modern labour market. The owners of mines and mills organized their labour force in such a way as to combine mechanisms of attraction, more-or-less forced recruitment methods, and forced retention of labourers. The two principal ways of attracting people were the combination of better wages, something possible in the new rich mines, and the opportunity labourers had to work for themselves during the weekends.Footnote 29

Many testimonies and ordinances indicate that the notion of “hired” was interpreted liberally in relation to mine labour: coercion was very common, and it was permitted under various circumstances because mining contributed to the royal “fifth” (quinto) – a tax imposed on silver production. The Spanish, for example, had the right to take indigenous people living in the vicinity of their mines and oblige them to work. This activity was sometimes known as “hunting”.Footnote 30 This right was already enshrined in Toledo’s ordinances.Footnote 31 There were other practices in relation to labourers, including the abduction or retention of their wives, and the pursuit and capture of runaways. There are documents that record the “sale” by native authorities of labourers; we have treated then as hired labour. Working in a mine, however, meant the possibility of earning more money, principally for those who were specialists and could earn better wages. Many indigenous people acquired technical knowledge relating to the amalgam process in Potosí, and, with it, they could command higher wages in new mines such as Oruro and San Antonio de Lípez.Footnote 32

MITA, TRIBUTE, AND LABOUR: A DISCUSSION

Toledo’s enduring reforms profoundly changed the colonial reality. In our article, we stress the relevance of the mita in the organization of labour relations. This hypothesis is based on the number of people directly forced to work in the mines and mills, on mita’s role in the mining boom at Potosí, and, principally, on the related migrations that modified the demography of the Viceroyalty and influenced almost all other forms of labour. The mita also occupied a central place in official concerns: it was present in debates, correspondence, and viceroys’ reports, while the tribute lost importance. In our analysis, we reconsider some classic interpretations, focusing on the tribute, of the mechanisms that forced native peoples to work in colonial enterprises. These mechanism, we believe, were very important at the beginning of the colonial period, but over time they lost their centrality because of the transformation of the economy and society in the Peruvian Viceroyalty.

How did the Spanish oblige native populations to participate in the colonial economy as labour? Assadourian proposed a number of interpretations for the colonial period that have profoundly influenced the historiography,Footnote 33 and we now re-evaluate them, focusing on labour and tribute. Assadourian wrote that the tributes indigenous people had to pay increased significantly, first with the inclusion of the yanaconas in 1566 and then with the reforms introduced by Viceroy Toledo, who augmented the value of the tributes each community had to pay and monetized them.Footnote 34 These reforms pushed native people to sell their labour or goods, thus stimulating the internal economy and augmenting royal incomes. Demography and the economy – Assadourian argues – developed in reverse, at least until 1630. Demography was the limiting factor in the growth of tributes: the size of the native population fell. This drove the government to put mining at the centre of its utilitarian politics.Footnote 35 Assadourian analysed the shipments of silver to Spain and the increase in royal incomes as indicators of economic growth and of the increase in the tax burden. In particular, he emphasized the differential pressure on native peoples, both in tributes and in labour, between Mexico and Peru, where the burden was much worse.

We base our discussion of Assadourian’s hypothesis on TePaske’s impressive work in collecting data on and interpreting royal income and expenditure in Spanish America.Footnote 36 Drawing on his work, we used two sets of data taken from the records of Potosí’s Caja Real:Footnote 37 on tribute income and silver production. Tributes were an explicit component of royal income, unlike the other obligations that the native people had to fulfil, so we prioritized the colonial obligation, which can be analysed as serial data and quantified. We know that other demands were made that are difficult to quantify. For example, the forced acquisition of goods, where native people were compelled to buy unnecessary goods sold to them by local authorities at high prices; services that natives owed to their authorities, such as transport using their own animals; and food and services they owed to the priests. These are not included here. The data on silver production were processed by TePaske, based on the Potosí royal incomes (Figure 2). We also looked for data on the mita, both theoretical and effective. The data available are not all of the same quality, but we can observe a general tendency. Finally, we added information on population (Table 2).

In Potosí, tributes and mining taxes accounted for ninety per cent of royal income during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 38 Serial data on both show how they developed differently over time. To explain this variation, Klein suggested that, in general, the royal fifth tax was linked to silver production, while tributes followed indigenous demography.Footnote 39

However, the tribute data show a closer relationship to colonial politics. We observed four cycles in the tribute series, although a small variation at the end of the period could be interpreted as a fifth cycle (Table 1). Before Toledo, tribute income accounts for just thirteen per cent of total income reaching the royal treasury, and it was not especially important, measured in pesos. At that point, few repartimientos de indios were paying in Potosí, and those that did paid infrequently. With Toledo, three important changes occurred: it was made compulsory for the yanaconas to pay; most of the encomiendas lapsed and the tributes associated with these rights reverted to the Crown; and there was an important and successful official effort to oblige all tributaries to comply with their obligations. Royal incomes increased in a clear context of population decline, as Assadourian noted. However, from the beginning of the seventeenth century tributes started to lose their relevance compared with the mita, not only for the royal treasury, but also for the authorities. One sees a clear and rapid decrease in tribute income. The fourth cycle shows relative stability in those incomes, which were at their lowest level during colonial times, even though the number of repartimientos obliged to pay the tribute was greater. The last cycle was brief, and showed a sharp decrease in expected repartimientos and a slight, but significant, increase in tributes: those were the years of La Palata’s general inspection.Footnote 40

Table 1 Tributes: royal treasury of Potosí, 1560–1700.

Source: TePaske (http://www.insidemydesk.com/hdd.html)

* Yanaconas were not included

Toledo’s government marked a period of unprecedented involvement by the colonial state and its agents, organizing and controlling tributaries. Their presence led to a temporary increase in tribute income. However, at that time, the principal concern was to organize the collection of the royal fifth,Footnote 41 and so the state stopped pressing indigenous labourers in relation to tribute and instead continued to press them in relation to the mita. Table 1 shows that, over time, although more repartimientos were obliged to pay tributes to the Crown, not all of them did so every year. In Potosí, tributes lost their importance in terms of value, since taxes on mining production became the chief source of income.

Regarding the demographics of the seventeenth century (the second factor in Assadourian’s argument), massive migrations in the Andes seemed to be related to mining activity since a large proportion of the labour force was directly or indirectly involved in silver production. When it comes to assessing this relationship, the worst problem we face is that most of the regional silver boom took place between the two general inspections (Toledo’s in the 1570s, and La Palata’s in the 1680s) in which the Andes population was enumerated. A second problem is that those inspections excluded an important part of the indigenous population living in the cities that had emerged around centres of silver production. To compensate for this, we used other evidence that shows the direction of migration during the seventeenth century (Table 2), and this implies we need more than Potosí to understand that migration: we also need the mita. The evidence comprises two observations: first, that it was the region around Potosí that grew most; and, second, that the provinces that lost most in terms of population were those obliged to send mitayos.

Table 2 Distribution of indigenous people recorded in the general inspections of Toledo and La Palata (%)

Sources: Toledo (Noble David Cook, Tasa de la Visita General de Francisco de Toledo (Lima, 1975)); La Palata (Ignacio González Casasnovas, Las dudas de la corona. La política de repartimientos para la minería de Potosi (1680–1732) (Madrid, 2000)).

Mining, mita, and migrations were strongly connected, as many migrants from the northern mita provinces did not return to their homes, and stayed in Potosí, as we can see in Table 2, which summarizes the demographic changes that occurred in the Peruvian Viceroyalty.

To explain the mechanisms developed by the colonial state and that permitted this kind of migration – probably as an undesired effect – we propose to separate tributes from other forms of labour, and to examine what happened between the 1570s and 1680s.Footnote 42 In some cases, trends coincided, but in many others they did not. We found three different situations: one in which some tributaries had to pay their tributes in money, and they worked to earn this money; another in which they had to work as forced labourers (mitayos) and to pay their tributes as well; and a third in which they sometimes had to work and were not obliged to pay tributes in money, as was the case with the yanaconas mentioned earlier.

Regarding tributes, Toledo reinforced a tendency that had already begun and that might explain the timing of migration: most of the tributes were paid to the Crown at the royal treasury and not to the private sector encomenderos. This was a consequence of Crown policy, started in the 1560s, to eliminate the social, political, and material power of the encomenderos. As a result, indigenous people were no longer subject to a particular beneficiary, a situation that allowed labour to migrate and to be recruited for the most important activity benefiting the Crown: mining. In this context, Philip II said about the mine labourers: “The profit that one of these natives [mine labourer] generates is greater than that given by twenty tributaries”.Footnote 43 Mobility disfavoured the control that native authorities had on their people and thus affected the payment of tributes. However, although the officials knew from the beginning about the decrease in these incomes and about the massive migration, they took no action until the arrival of La Palata in the 1680s.

Geographical mobility was, and still is, important in the mine labour world. We believe that two factors permitted and promoted mobility during the seventeenth century: the fact that the tributes were paid to the Crown, and not to private individuals; and the organization of the mita. Becoming royal tributaries, without personal links to a particular Spaniard, allowed indigenous caciques, groups, and people to “choose” where to sell their labour or goods, and to earn money to fulfil their obligations. Further, the power that Potosí mine owners and the authorities had at that time allowed them to prioritize the mita, arguing that it helped them to increase the royal fifth. This had a practical result: tributes decreased dramatically during this period, but the authorities took no action.

There were two types of labour: one mobile and one attached to the land. The first group, people affected by the mita, who fled – either to avoid the obligation or to find money for a substitute – provided labour for various activities that did not rely on forced labour: these activities included work on estates, in other mining centres, and in the transportation of goods to supply the important urban market that was developing during the seventeenth century. The second group was established by the agricultural estates, which promoted greater geographical stability for labourers, using a range of mechanisms to bind them to the land. One such mechanism involved Spanish landowners paying the tributes to the Crown and the indigenous labourers being indebted to them in return. Another involved landowners attracting or accepting fugitive tributary natives, who became yanaconas, thus establishing a personal relationship with the Spanish and becoming less free to move.

There has been a conflicting debate about the demographic crisis at the end of our period, in the 1680s and 1690s. On the one hand, the royal authorities claimed that the principal cause of the decrease in tribute income and in the number of mitayos was the indigenous people running away and avoiding their colonial obligations. On the other hand, indigenous organizers of the mita in Potosí maintained that people were obliged to flee from their rural towns because of abuse by the caciques, the local Spanish authorities, and because their lands had been sold. Moreover, during the seventeenth century, further burdens were added to the existing ones – tributes and mita – already imposed on the natives. One of these became the most important: the forced acquisition of goods, sold by local Spanish authorities to the natives, from the first half of the seventeenth century. Indigenous people were forced to buy non-useful and very expensive goods sold by the local authorities, a practice legalized by the Crown in the 1750s. This practice had its origins in the seventeenth century, when the Crown began to sell official positions, especially that of local governor. The appointee then attempted to recover the money paid to the Crown by selling goods to the tributaries.

Although beyond our period, a description of what happened during the eighteenth century helps to put the previous two centuries into a broader context. According to various sources, during the first half of the eighteenth century mita substitution and the compulsory purchase of goods by indigenous people were the most oppressive obligations for the royal tributaries. In this context, royal officials also made various attempts to oblige indigenous people to pay their tributes regularly.Footnote 44 In the context of the new reforms introduced by the Crown, the native response to all these pressures was the increase in violence that began in the 1740s, culminating in massive rebellion during the 1780s. The compulsory purchase of goods was subsequently forbidden, and the way tributes were paid was radically reformed: people had to pay per capita, and the tribute payable was related to their place of residence and not their place of origin. The indirect forms of labour control discussed earlier lost much of their significance. As a result, in the late 1780s, for the first time in the colonial history of Charcas, the value of the tribute collected by the royal officials exceeded that of silver production. The importance of the tribute grew significantly and became the main source of Crown income in the Andes.

COLONIAL POLICIES AND SHIFTS IN LABOUR RELATIONS

In presenting our case study of the definitions of labour relations proposed by the Collab, we want to stress, first, that all the labour relations we have noted existed in a colonial context. This context influenced all labour relations, especially those of indigenous peoples. Second, we use the term “state” in a broader sense, as proposed by the editors, and, of course, as distinct from the “nation state”. During colonial times in Spanish America, political power was devolved to various decentralized poles, often with conflicting interests. However, there was a significant difference between what we have called private individuals and the authorities, although in many cases they were one and the same. Third, one of the characteristics of the relationship between conquerors and natives was the role of indirect rule. This characteristic partly explains the survival of Andean communities, because they maintained their right to organize themselves – at least at some levels – and retained part of their original lands and resources – in theory – as long as they fulfilled their colonial obligations, namely tribute and mita. Platt proposed the notion of “pact” to understand this relationship.Footnote 45

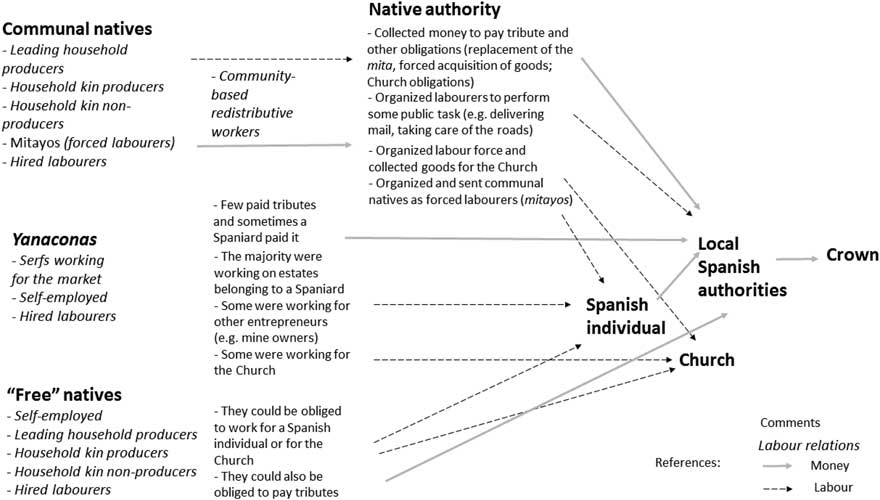

In what follows, we analyse each tributary category using the Collaboratory’s taxonomy (Figure 3). Broadly speaking, almost all the population living on communal land were household producers, leading and kin, at least part of the year. In addition, and because of their reciprocal relationships, they also had to fulfil communal obligations, such as tribute and mita. Then, part of the year and sometimes during a whole year, a percentage of the tributaries and their families migrated to Potosí to work in the mines or mills, or they went elsewhere to earn the money they needed to meet their communal obligations. People belonging to a community (i.e. everybody except the yanaconas and those we have termed “free” indigenous people) had to fulfil jointly all the many obligations, as we have seen above, and not just the tributes. The cacique was responsible for fulfilling these obligations to the colonial authorities. Some wealthier groups or people were able to avoid selling their labour: instead, they sold their goods in urban markets, went as merchants to various parts of the Viceroyalty, or had enough llamas to transport their goods or those of others.

Figure 3 Overview of labour relations during the seventeenth century, Charcas.

All the relationships we have noted in the previous paragraph were within the ethnic group; however, indigenous peoples also had labour relations with the Spanish. In the mita system, for example, we find a combination of inter- and intra-ethnic relations. On the one hand, there were the colonial obligations all indigenous peoples had as Crown subjects that legitimized the state-coordinated form of draft labour organized by Viceroy Toledo for the benefit of individual Spaniards; on the other, there was the asymmetrical reciprocal relationship indigenous people had with their native authority, which forced them to fulfil their obligations. All indigenous individuals were Crown subjects, but this relationship was mediated by their native authorities.

Although mita was not tributary labour in the sense proposed by the Collaboratory – because the polities did not benefit directly, as the mines were exploited not by the state but by individual Spaniards – initially only royal authorities had the power to force indigenous people to migrate and to work in mining, coordinated through their caciques. The benefit to the Crown was indirect: indigenous labour produced silver, and, owing to the royal fifth tax paid by private silver producers, this was the main source of the increase in royal income.

The state regulated the amount of money that mitayos received for their labour from individual Spaniards. This amount was less than the wages paid to hired labourers, and when the mita was first organized it was calculated per day. However, during the seventeenth century the miners regulated the mitayo’s weekly work, imposing a production quota, and the money they actually received was therefore less than the level theoretically set by the state. As mitayos they had to pay their tribute, for their food, all the equipment needed for their work, for the hospital, and the salaries of their priests and of the colonial authorities.

There were various types of indigenous people involved in Potosí’s mining activities: forced labourers (mitayos) as well as “hired” labourers and yanaconas belonging to the Crown. All of them were Crown subjects, although not all were obliged to work in the mines. Why did indigenous people who were not mitayos go to Potosí or to other mines? Colonial relationships explain this. For example, Spanish miners had the right to oblige a small number of indigenous people living close to their mines to work there, just because they were Crown subjects. In other mining centres in south Charcas we found people who had been forced to stay, by being locked inside a room for the night, or because their wives and children were prevented from leaving.Footnote 46

What we have here called “hired” labourers were people who went to the mines, attracted by the incomes they could earn there. They were usually “well-paid” skilled labourers, though it would be more accurate to say “better paid”; they were sometimes the same mitayos, working in their free time. Although they were free to move to other places and mines, they were not really free to decide to stay in their communities if they wanted. They could also be obliged to stay in a mining camp against their will. As we have already seen, they, too, had to find money to pay their obligations and not only for their survival: their reciprocal relationships with their communities “forced” them to go.

Among the yanaconas, we found no indirect rule, as they had no reciprocal obligations to their communities. However, they were also Crown subjects. In almost all mining centres, there were three different types of yanaconas: some worked for particular individuals (as a kind of servant), others for themselves (forced only to pay the tribute to the Crown), while others worked for the church (and paid tribute to the Crown).

There were also indigenous peoples living in places other than the communal lands, mines, and estates we have described. Many of them lived in the cities, sometimes with strong relationships to their communities, through paying their tributes, sending money for the mita substitute, or for other reasons; there was sometimes no such relationship. The latter were “free” indigenous people, who did not recognize a native authority, who did not work for a Spaniard, fixed to the land as yanaconas, and who did not pay tribute. They lived, avoiding obligations, on the margins, but they played a role in the colonial economy as traders or muleteers; sometimes, they worked in peripheral lands or mines, or as highland pastoralists. In the seventeenth century they were few in number, but by no means insignificant.

In summarizing the role of the state in labour relations, we would stress some of the factors that defined those relations. The first is that all indigenous people were subjects of the Spanish Crown, and that allowed private individuals and various authorities to force them to work. The state defined many of the tasks that almost all tributaries living in communal lands had to perform. They were also obliged, by the state, to send some of their men to work in specific mines and mills, and to pay their tributes to the Crown. The state set the wages that mitayos received and, in general, all obligations relating to this particular form of labour. Other non-official obligations, such as paying for their substitutes in the mita, or buying the obligatory goods sold to them by the local governor, could be considered indirect methods to force them to acquire money, through the sale of their labour or goods. Finally, the passive role of the authorities was also important: for example, like the encomenderos before them, royal officials did not control the tribute indigenous people had to pay to the Crown, or their spatial movements.

CONCLUSIONS

Right from the beginning of the conquest, the Spanish took advantage of the Inca’s organization of labour. However, in a colonial context labour relations changed significantly. The architect of the changes that affected those relations until the end of the eighteenth century, and, in some respects, until independence, was Viceroy Francisco de Toledo. In this article, we have stressed four aspects of his reforms that were important for the new configuration of labour relations: the organization of the mita, the extinction of the encomiendas, the increase in the amount each community had to pay, and the obligation to pay in money. The reforms freed the tributaries from their encomenderos and permitted the massive migrations that took place from the seventeenth century onwards.

Why would a native leave his land and work for the conquerors? The historiography traditionally argues that the increase in the tribute, and the obligation to pay it in money, forced them to migrate and to look for ways to earn money in order to pay it. This is, of course, part of the answer. However, we have seen that there were also indigenous people who were not obliged to pay, but instead required to work for the Spaniards (yanaconas); further, the obligations involved more than paying tributes, and the other obligations were sometimes more important. It was the colonial relationship indigenous people had with the Crown that legitimized the different forms of direct and indirect coercion.

Direct coercion was exerted, for example, through the mita system, and through some royal labour regulations. Indirect coercion is more difficult to identify. Indigenous peoples, and, more specifically, those peoples of more limited means, were forced to leave their land and to look for ways to earn money to fulfil their colonial obligations. There were at least three reasons for this: the need to pay for substitutes for the mita, the obligation to buy goods sold by the local governors, and the tributes themselves. The latter lost their importance during the seventeenth century, while the first two became more important. Regarding the Collaboratory’s taxonomy, we want to stress that, although the state regulated the tasks and identity of labourers, the major beneficiaries were private individuals.

Why did indigenous peoples fulfil their obligations? The key factor was indirect rule: those natives belonging to a community wanted to retain their rights by collaborating with their communities, paying their tributes, and meeting all other obligations. In exchange, they could organize their own government and keep their lands.

Natives who did not belong to a community, typically the yanaconas, did not have reciprocal labour relations and communal obligations. Some of them had inherited their yanacona status and worked for a Spaniard right from the start of the conquest. Some had tried to escape their obligations, principally the mita, by running away and ended up as yanaconas on estates or working in other enterprises. Royal officials did not force them to return to their communities, partly because there were an increasing number of Spanish landowners and mining entrepreneurs who did not have the advantage of forced labour – such as the mitayos – and who therefore needed such labour.