At first glance, there is nothing unusual about the fact that, in 1790, a woman went to a magistrate in Mexico City to request money from her husband while their divorce case was pending.Footnote 1 Everything about the lawsuit seems ordinary, even down to the litigant's name, Doña María García. Decades of historical scholarship on gender have familiarized us with women just like her, women who tactically employed the courts of the Spanish empire in the larger “contest” that made up gender relations in the era. Histories of women veritably brim with female litigants who used the justice system to win small victories in their battles for autonomy from marital obligations or to rein in philandering, shiftless, or abusive lovers.

On the surface, the incongruity between Doña María's attempts to extricate herself from her marriage while still demanding that her husband provide her financial support poses no challenge to the larger lessons we have gleaned from the history of Spanish colonial women and the legal system. Women's legal tactics might have been successful in the short term, gender historians tell us, but in a more general sense, the litigants who won these legal battles ultimately lost the war. A woman bringing suit might prompt a priest or royal official to march a straying husband back to the marital bed, but only by ratifying the patriarchal authority of the Church or royal state to intervene in marriage; a woman might get her husband locked up for beating her, but then be forced to live in the seclusion of a convent or lay religious house (recogimiento) in order to protect her honor. And a woman like Doña María García might successfully achieve an ecclesiastical divorce (a permanent separation without the ability to remarry), but the “right” to alimony she sought positioned her as a perpetual economic dependant of her husband.

The theoretical lens through which many U.S. and quite a few Latin American historians have been trained to view court cases refracts two theoretical traditions. Historian Ana Lidia García's recent study of marriage in nineteenth-century Mexico tightly encapsulates the first tendency, to place gender relations within the loose Marxian framework of theories of hegemony. “The subordinate role of the wives and lovers … did not facilitate the construction of an alternate discourse of power,” García writes, “but rather one of resistance within the structures of male domination.”Footnote 2 In this view, women—who often regardless of social class or color status represent the “subaltern” of Antonio Gramsci's culture-based theory of power—act as real historical agents. Their ability to “resist” power is presumably discernable in the archival record, but its ultimate outcome is to solidify male authority.Footnote 3

The second tendency that has predominated in historical studies of women and the law in the Spanish empire, one as much methodological as theoretical, derives from the so-called “linguistic turn” of the late 1980s. Historians, including many who place their contributions within an essentially materialist framework such as hegemony theory, regard court cases as textual remnants of diffuse but interrelated codes of power, or discourses. For many gender historians, the linguistic turn has meant recounting courtroom tales sensitive to the ways they reveal cultural logics of gender power, displacing but not erasing the possibility of material explanations of domination.Footnote 4 Our methods of reading cases have become synonymous with “decoding” women's statements in legal conflicts in order to reveal how gender worked as an organizing principle of authority, expressed through culturally embedded narratives and tropes.Footnote 5

In this respect, historians of gender in the Spanish empire have for almost three decades now engaged in a kind of theoretical acrobatics. Florencia Mallon, referring to Latin Americanist historians generally, has called this act “riding two horses at the same time,” or adopting two ultimately incommensurable theoretical and methodological positions.Footnote 6 In one, the agency, or the rational, conscious political actions of our subjects, is both possible and discoverable, and subjectivity can be autochthonous as well as ascribed. In the other, our subjects' possibilities for self-knowledge and representation are culturally pre-coded, and “experience” is reduced to the tropes through which it is expressed.Footnote 7

In this article I suggest an alternate way of approaching lawsuits as historical documents: to focus on the literal context—or praxis accompanying the text—of the initiation of a suit, rather than only on the legitimating narrative that the suit contains.Footnote 8 I regard the cases women in the eighteenth-century Spanish empire brought against husbands and lovers not only as objects capturing assemblages of discourses but also as historical events that occurred in and over time, and between and among diverse historical actors, events that were only in part recorded and preserved.Footnote 9 By refusing to equate the written record of lawsuits with “agency,” and the legal system with “structure,” and by investigating rather than assuming women's subjectivity in these cases, I aim to reveal a story that can provide release from the intractable contradiction of combining hegemony models with discourse analysis.

The many gender historians who use colonial court cases as their chief source material have been, in the main, content to accept such contradictions, and understandably so. It is easy to imagine Spanish law, almost more than any other “structure,” to be an oppressive and patriarchal domain.Footnote 10 Thus it is almost inevitable that we will find the historical subjects who operated in the realm of law, especially women who stood before judges, to have been forced to capitulate to or conspire with structures of domination.Footnote 11 Of course, not all gender historians make exactly the same points about the constraints of law and the gendered history of legal practice; we scuffle over how patriarchal things were or how much autonomy women had.Footnote 12 But when the dust settles, we are seduced over and again into retelling the individual stories of female cunning and determination that this record contains. And we marvel at the sheer quantity of such stories and the numbers of women who turn up in the empire's judicial record.

Still, it is difficult to find historians who connect women's very presence in these legal dramas to “agency” or “subjectivity” in more than an elliptical way. For example, historians provide impressive statistics about women involved in criminal cases against men, but fail to untangle the status of plaintiff from that of victim.Footnote 13 Or we might learn that women could constitute up to 40 percent of civil litigants, be involved in one-third of criminal trials, and make up the overwhelming number of litigants in divorce cases, but still be left with vexing questions about the precise role women played in crafting the documents we read and the production of the archives that we consult.Footnote 14

This perhaps owes to the nature of the sources. The judicial archive in the Spanish empire has its own hidden history, and it is difficult to know how much of the legal activity that occurred is recorded in the yellowing papers we find today. But there is another reason for our silence on the law: we often use legal suits not so much to understand the operation of law in women's lives but instead to understand the world beyond the courtroom, making the numbers of suits filed and even legal context for suits—jurisdiction, expected outcome, procedure—somewhat beside the point. The pages of suits overflow with tiny handwritten recordings of mundane judicial actions such as client notifications and interim judgments. Yet our arguments gravitate toward narratives in the suits that seem to provide information we seek on gendered culture and “everyday life,” such as women's opening petitions or lawyers' arguments, which are frequently dismembered from the larger body of the cases. In this way, our use of legal suits, and indeed our entire approach to law, relies on a gendered, cognitive distinction between the world of the “everyday” and the world of the “law.”Footnote 15

At the same time, scholars who are otherwise highly attentive to questions of power tend to read women's statements in Spanish legal suits with a surprising faith in their transparency. Our subjects were, on the whole, illiterate, and the words that remain in archives were written by agents of the colonial state, anonymous patrons, or hired legal representatives.Footnote 16 Nonetheless, our attention is drawn to the seemingly unfiltered parts of suits, particularly witness testimony and litigants' opening statements, issued before procurators took over the cases and lawyers rendered their grand arguments. These statements have been described by diverse scholars as “rambling,” “gossipy,” and “raw,” as well as “unrehearsed” and “near verbatim.”Footnote 17 Another historian claims that statements in colonial criminal suits in Villa Alta, Oaxaca, “represent the spontaneous words of the common people.”Footnote 18

By examining women's petitions as actions rather than narratives, we can move beyond the irresolvable question of whether legal texts, or any texts, can capture “spontaneous words” that express “common people's” everyday understandings of gender relations. Instead, the approach that I employ addresses the deceptively simple question of how women's engagement with the justice system produced the bountiful suits against husbands and lovers that we find in the judicial archives in diverse reaches of the Spanish empire. Working especially with the opening petitions or initial accusations turned over to the courts by women suing husbands and lovers, I seek to reexamine basic questions about the origins of women's lawsuits: what came before (their pre-history), and what they were for (their goals.)

I draw the evidence presented here from a review of hundreds of cases associated with marriage or consensual unions, especially divorce, adultery, abuse, and alimony suits aired in secular royal (civil and criminal) jurisdictions and ecclesiastical courts. Geographically, my focus is imperial rather than colonial. That is, it analytically pulls together Spain and its American colonies. I give special attention to the colonial capital cities of Mexico City and Lima and their rural environs; provincial jurisdictions in Oaxaca, Mexico, and Trujillo, Peru; and two jurisdictions in Spain, including the local court of a rural Castilian region known as the Montes de Toledo, as well as a high appeals court (chancellería) in the city of Valladolid.Footnote 19

By exploring first the pre-history of women's suits and then their goals, I draw conclusions that are both synchronic and diachronic. In part, this is a methodological exercise designed to show how attention to the actions surrounding the initiation of court cases complicates the ontological categories of agency and structure, the “everyday” and the “legal,” that we bring to our analysis. But I want to make a historical argument as well. The opening texts in lawsuits reveal that the gendered operation of the law was always far more complex than mere female subjugation to literate male rulership within the realm of writing. Indeed, during the early part of the century, the writing of the lawsuit was quite often incidental to the justice women sought. At the end of the eighteenth century, however, a number of women in the empire generated a new form of legal subjectivity that privileged the written lawsuit as a legitimating text. In a rich twist, these women used their petitions to draw the very divisions between the “verbal” and the “written,” and the “extralegal” and the “legal,” that scholars now use to understand their legal actions.

It is important that this development not be seen as teleological. It was not unequivocally “liberating” for female litigants, and it did not take place evenly throughout the empire or uniformly among all women. Not surprisingly, it was a development that was predominantly, though not exclusively urban, ethnically “Spanish,” and perhaps even “bourgeois” in character. But less predictably, the development of this new legal subjectivity was as much an American as a European phenomenon, and was in fact as notable if not more pronounced in the capital cities of the colonies as on the peninsula. Particularly through the use of the secular civil court system, a growing number of female litigants began to act on a concept of justice that distinguished between the extralegal world and the lawsuit, and in which the petition, rather than being simply a vehicle for obtaining justice, was a crucial element in the creation of an increasingly secular, legal form of female subjectivity. In this new way of viewing the legal system, the suit itself, rather than the authority of judges or actions of the community, became the locus for “justice.”

The Pre-History of the Petition

When the first-instance civil judge in the Mexican city of Antequera—today known as Oaxaca City—received Doña Petronila de Muñar y Puente's formal petition (demanda) dated 5 October 1731, it was not the first he had heard from her.Footnote 20 She had appeared two days earlier requesting that the judge warn her second husband, a local storeowner, to keep his hands off the property she had brought into their marriage. The alcalde complied with her request and issued a verbal warning to the husband, and sent her to be confined (depositada) in her sister's home.

None of this was written down. Perhaps this gave Doña Petronila's husband an excuse to disregard the judge's warning and break into her empty house to remove several valuable items. Two days later, Doña Petronila returned to the judge with a formal petition initiating a civil suit against her husband over the possession of her belongings. She began by recounting the earlier legal interaction she had with the alcalde, and claimed that her husband's insubordination had forced her to file in writing. The hand that crafted her statement clearly belonged to an educated patron, a hired scribe or legal agent (procurador). But the bottom of the page bares her own shaky signature.

As in Doña Petronila's case, the first pages of lawsuit dossiers often are not so much opening salvos in battles between lovers and spouses as crescendos in disharmonious relationships that began months or years earlier. Judges frequently had entered into these relationships long before the suit began. When women in Spain and Spanish America sought out judicial officials in their disputes with husbands or lovers, they often did so first by complaining verbally to a judge without the intervention of scribes or lawyers, entering a realm that contemporaries called lo extrajudicial, and engaging in a practice that, though it involved no writing, was nonetheless legal.

The small number of eighteenth-century divorce cases that remain in Trujillo's ecclesiastical archives—twenty-one—provide a concise sample to illustrate the larger pattern. Women, most of whom used the honorific title doña, which denoted elite status, filed all but two of these cases. More frequently than not (fourteen cases), an unwritten, verbal pre-history of intervention by priests, church, and royal judges trailed behind the opening petition for divorce, and litigants began these petitions by cataloging the verbal complaints they had made before deciding to file an official suit.Footnote 21

Since Church officials aimed whenever possible to reunite estranged couples and preserve the sanctity of marriage, they often held what they termed “extrajudicial,” face-to-face encounters between parties (careos) to work out a peaceable solution. Such was the case when the Bishop of Arequipa mediated a contentious dispute between Doña María Romero and her husband Ygnacio Salgado, in 1786. He listened to their complaints and then reunited the couple without generating a single piece of written evidence. Pages of official documentation only began to pile up when the bishop tried to levy a hefty extrajudicial fine against Salgado for adultery, a highly unorthodox decision that set off a firestorm with secular authorities.Footnote 22

The option of lodging a verbal complaint in a domestic dispute rather than launching an official, written lawsuit would be especially appealing to poorer litigants since it avoided the risk of incurring what could be very steep court costs. The fees of scribes, judges, and lawyers could exceed 200 pesos in an average formal civil case brought to sentence in the Spanish empire. To put this in perspective, at the end of the eighteenth century 200 pesos would purchase an African slave child in Lima, buy some two hundred casks of Andean wine, or provide a physician's salary for a month or a wet nurse's pay for a year.Footnote 23

We might expect the many legal personnel involved in a case filed before a judge in any jurisdiction of the empire to encourage formal disputes since they could charge for each element of the suit, from the official paper embossed with a royal seal (papel sellado) required for written petitions, to scribes' compensation for the mere act of notifying the opposing party that a motion had been filed. And, to be sure, everyone involved in judicial sphere, even the courthouse doormen, could find creative ways to squeeze pesos from litigants.Footnote 24

Unhappy women surely provided a ready clientele for these legal agents. A long history of codified law in Spain and its dominions—ranging from the medieval Siete partidas and local fueros, or regional privileges, in civil matters, through canon law, on to Spanish American conciliar decisions about divorce cases—permitted women to sue their husbands for annulment and divorce, to claim mismanagement of their dowries or the property they brought into marriage in civil court, and to charge husbands in criminal courts with sevicia, or excessive physical abuse.Footnote 25

In practice, though, judges exercised broad discretion regarding whether to handle domestic disputes summarily or accept them as formal cases, a discretion dependant on the type of case and local custom. Where there was money to be made, such as in dowry disputes between elite couples, cases streamed in. Such suits were commonly aired in all regions of the empire and tended to involve complex records of debts and investments, easily amounting to claims of thousands of pesos and suits of thousands of pages. Yet as Josef Juan y Colóm explained in his 1773 Instrucción a Escribanos, women's suits over dowries or alimony technically fell into the category of “executivos,” or summary cases that required no formal process of litigation or written record.Footnote 26

There were also disincentives for judges to hear cases. Cultural, professional, and legal pressures encouraged an informal—and gratis—resolution of disputes seen to be “petty” or of “small entity,” including many of the kinds of disagreements between spouses that women might bring to a judge's attention.Footnote 27 “Mercenaries” is how one lawyer giving a speech in Valencia described attorneys who took on “frivolous” lawsuits or drummed up business among impassioned litigants such as fighting lovers.Footnote 28 Moreover, Spanish law's built-in provisions for pro-bono representation for widows, Indians, and the poor undoubtedly combined with such professional codes of honor to prevent lawyers from encouraging quarrelling spouses to take their fights to the bench for a fee.Footnote 29

So rather than fanning the flames of domestic fires, many judicial officials sought to tamp down their sparks at the threshold of the court, at least initially. In 1795, Doña Mariana Duárez of Lima testified to as much with a written recounting of how the judge had first responded when she approached him to intervene in a dispute with her husband over his theft of household items and dalliances with a female slave: “You told me litigation was not necessary in a matter so clear and of such small magnitude.”Footnote 30

As might be expected, the women most likely to transform verbal complaints into written, formal suits were those who had some access to money to pay court costs and exposure to Spanish legal norms, and who lived near tribunals. In colonial Spanish America, this meant that it was mostly creole (ethnically Spanish) women who presented written demands against their husbands. Their visits to the scribes who lined the streets off city squares were a spectacle that would later capture the attentions of nineteenth-century costumbrista artists. But proximity—whether geographical to courts and legal personnel or cultural to Spanish legal culture—cannot by itself explain what led certain women to sue their husbands and lovers, and this deserves more scrutiny.

It is true that upper-class urban women, who might receive education in convents or with teachers known as “amigas” or “migas,” acted as civil litigants against husbands more frequently than did rural women. Elite women predominated in both divorce and civil litigation.Footnote 31 But one did not have to be able to read or write in order to sue, especially given the near-universal reliance on formally educated men (letrados) and scribes to craft petitions or file motions.Footnote 32 To underscore this point we need only consider that slaves in colonial Spanish America found multiple ways to move through the lettered world, including the world of litigation, despite their subordinate positions and overwhelming inability to read and write.Footnote 33

Even if literacy was no precondition for suing, a chronic lack of scribes and educated individuals to provide legal counsel in the countryside surely hindered rural women who wished to pursue formal suits.Footnote 34 All women who lived in regions remote from Spanish tribunals faced obstacles to filing written suits and especially appeals. When a rural woman had exhausted authority figures close to home, her next appeal often was to one residing in a city far away. Many rural women pursuing cases across vast distances decided that, instead of bouncing with their belongings on the backs of mules through the rugged terrain of the Andes or the Sierra Zapoteca, only to arrive in a strange city to sue, they could simply send a piece of paper. But paper had to be delivered, and thus they needed a patron to file their case. For example, Doña Marcelina de la Cruz, who claimed to have been abused by her husband for years, unsuccessfully issued several verbal complaints to the local Church official in the Peruvian coastal town of Piura. Not until she achieved the help of a man named José Montero was she able to formalize a petition and get it to the bishopric of Trujillo in order to officially file for divorce.Footnote 35

For rural women in particular, justice often began not at the bench but in the parish. Many priests conceived of themselves as peacemakers and discouraged litigation by repeatedly sending unhappy women back to their husbands, as doña Antonia Leiva's priest did with her no fewer than three times.Footnote 36 But curates also might foment women's litigation, including secular cases.Footnote 37

Cases brought by rural, indigenous women reveal especially extensive verbal pre-histories, often involving priests or community elders. This might, in part, reflect the inaccessibility of legal personnel in the countryside, but it also points toward an oral legal culture in native communities, where local justice, administered by indigenous authorities associated with the town's cabildo, was often carried out without “papel sellado” at all.Footnote 38

This should not lead us to conclude that rural indigenous women were isolated from Spanish courts or colonial legal culture. As Brian Owensby remarks, “By 1700, few Indians would have thought that the law was ‘irrelevant’ or ‘alien’ to them. Quite the contrary.”Footnote 39 Each indigenous town council was to count among its ranks a Spanish-speaking notary who was trained in the formulas of the law and theoretically available to women involved in domestic disputes. Furthermore, whether they resided in cities or rural villages, native women, far from being blocked from access to secular courts, had access by virtue of their caste designation to special jurisdictions called the Juzgado General de Indios in Mexico, and the Defensoría de Naturales in Peru. And if they could figure out how to transport themselves or their petitions across long distances they could bypass lower courts and appeal directly to the high courts and even viceroys who resided in Lima and Mexico City.Footnote 40 It might seem an unlikely image, a stand-in for the Spanish king in the colonies, clad in powdered wig and velvet coat, turning his attention to the marital complaints of a poor native woman. But such scenes certainly occurred.Footnote 41

To understand the interplay between verbal appeals and written suits among native women, let us consider the petition filed in 1795 by Felipa Huesca, an indigenous woman from the Gulf coast pueblo of Xicochimalco, Mexico. She utilized the special legal privilege extended to natives to take her case directly to the viceroy, but only after exhausting a series of other options. She had first complained in person to the local priest after her husband, Pedro Colorado, with whom she quarreled frequently, sold several heads of her cattle without her permission. Pedro beat her for her trouble. She then submitted a verbal complaint about both the cows and the physical abuse to a higher secular authority, the subdelegado of Xalapa. This royal official threw Pedro in jail, but after eight days and a chat with the local priest, he “reunited” the couple. Felipa somehow delivered a written civil petition recounting her husband's offenses and her earlier attempts to achieve justice to the Mexican viceroy, the Conde de Revillagigedo, in the capital city. The statement was rife with orthographic errors and colloquialisms, but it followed the standard form of an opening complaint in a criminal suit, or auto, and it was recorded on the required embossed paper, to which she did not affix her signature because she did not know how to write.Footnote 42

The diverse indigenous women labeled in Spanish courts as “indias” not only had access to special jurisdictions, but were also exempt from court fees and their cases were, by law, to be treated as summary. This rule was bemoaned by the officials of Xochimilco, in central Mexico, in at least three separate cases involving domestic violence between indigenous spouses in the 1770s. A local Spanish official there tried to pass on a legal bill from two officials in Mexico City to the noble father of a native woman who had been abused by her husband, complaining, “God isn't paying for all this.” The alcalde mayor of the region likewise seemed frustrated with the pro bono status of Indian suits. In another case, he reported to the viceroy that the judges in his jurisdiction in the town spent all of their time working for free on Indian suits and on negotiating the debts that Indians ran up with surgeons after drunken fights. Although he sought to formalize the compensation structure for court officials' work, he nonetheless seems to have understood his role of arbiter of indigenous cases as settling cases out of court. He defended his performance as a judge by stating that the “due completion” of his “obligation” as a judge was to swiftly administer justice in the “extrajudicial realm” (en lo extrajudicial).Footnote 43

Thus there were many factors, ranging from cultural and linguistic to jurisprudential to geographical, that tended to concentrate disputes between indigenous spouses and lovers in the verbal arena, even when Spanish officials were drawn in as arbiters. It is easy to become transfixed by indigenous women like Felipa Huesca, whose efforts to get her husband to return the value of her small herd of skinny cows eventually materialized into a document that the viceroy held in his hands in 1795. But we must acknowledge that this achievement would have been more difficult for her than for urban women in the empire.

In fact, viewed comparatively, very few rural women of any caste, and even fewer rural native women, appear either as plaintiffs in formal, written criminal prosecutions or as litigants in civil litigation.Footnote 44 Indigenous women in rural Oaxaca are particularly spectral as principal civil litigants against husbands and lovers. My review of over one thousand civil cases in the districts of Villa Alta and Teposcolula turned up only two instances of Indian women initiating a written suit in civil court over matters pertaining to divorce, adultery, alimony, court costs, or female “deposit,” and fewer than a dozen related to physical abuse or neglect.Footnote 45 It bears note that during the century widows and single women were marginally more active in property disputes in Teposcolula than in Villa Alta, even though both regions were predominantly indigenous. Such variations are a further reminder that “Indians” did not share a single legal, political, or gender culture.

The pattern of relatively few Indian women appearing as litigants in the registered Oaxacan cases parallels a tendency I identified in the court cases of Trujillo, Peru, a majority indigenous province that, while claiming a sizeable colonial city on its western coastal edge, otherwise was spotted with coastal haciendas and rural pueblos.Footnote 46 The criminal records of Trujillo's provincial magistrate, the corregidor, who tended to handle rural cases, contains only nineteen written complaints against men for domestic issues in the 1700s, and seventeen of these were brought de oficio (by the state). Women were far more active in the civil sphere, steadily initiating a third of all registered civil cases heard in three secular jurisdictions.Footnote 47 But, as in Oaxaca, few women of provincial Trujillo sued their husbands and lovers in civil court; gender disputes over divorce, alimony, court cost, and adultery constituted just twenty civil cases out of over two thousand heard in the 1700s.

It may seem logical that cultural proximity to Spanish as opposed to indigenous legal culture would make a crucial difference in determining which women formally sued their husbands and which did not. Contemporaries certainly thought so. One ecclesiastical judge in an indigenous parish in Mexico explained this by invoking ethnic stereotypes of Indians' unfamiliarity with the law, or more precisely, their tendency to abandon suits: “Since Indians do not know how to follow through with various judicial actions, it is easy to return [Indian women] to their husbands, no matter how great the offense.”Footnote 48 But we should be careful not to follow this priest in adopting easy ethnic explanations for the diversity in gendered legal practice, and instead critically examine whether it was the “hispanicized” character of urban women that endowed them with more legal “agency” than rural indigenous women, leading them to more frequently sue husbands and lovers.

Here it is instructive to consider gendered legal culture in the Spanish empire as a whole rather than only in colonial Spanish America. Evidence from the rugged region in central Spain known as the Montes de Toledo indicates that it was the rurality of women, rather than their “ethnic” or “cultural” distance from “Spanish” legal norms, that best predicted whose complaint might end up captured in writing. The legal actions of these peninsular women also complicate any crude equation of women's legal agency with their tendency to file formal lawsuits.

The Castilian peasant women in the Montes de Toledo—ruddy, hardworking types who could have stepped out of the windmill-spotted pages of Cervantes—were not particularly “dominated” figures. They frequently appeared in civil and criminal suits aired before a judge known as the Fiel del Juzgado, who ruled over the region's cases from a town council building in the imperial city of Toledo, perched atop hills no more than a two-day journey from their pueblos. They appear in these suits fighting with, cursing at, and conning their neighbors.Footnote 49 But, like indigenous women in the colonies, the married women of the Montes appeared in secular civil courts alongside their husbands, never against them.Footnote 50

Women in the Montes de Toledo were also present in about one-third of the criminal suits I examined. But these women were unmarried, and appear as objects, rather than subjects, in cases brought de oficio.Footnote 51 In cases of rape, seduction, or unfulfilled marriage promises, these women allowed cultural notions of community “outrage” and “scandal” in their small pueblos to do their legal work for them. Local justices such as Fernando de Arce, the alcalde of the town of Marjaliza, frequently took the authorial lead in single women's cases, which he brought de oficio, wrapping the cases they passed to the Fiel del Juzgado in a language of official responsibility for upholding community gender norms. For example, he reported in 1781 that it had “come to his notice as a public and notorious thing that a single woman named Paula Esteban was pregnant.” His statement made no reference to Paula's “right” to have the father pay for the baby's support, though ultimately that was what she sought. Rather, the “agent” in the case was his knowledge of the affair, and the gossip and scandal it caused.Footnote 52 That same year, de Arce again made liberal use of the passive voice when he reported to the Fiel that he “had been given notice by people of character in the town” that the unmarried Gabriela Ximénez was five-months' pregnant. As the case progressed, it became clear that the suit was a mechanism, effective in the end, which Gabriela used to prod her lover into fulfilling his promise to marry her.Footnote 53 She never appeared as a litigant or accuser at all.

Taken together with what I have been calling the “pre-history” of women's legal activities, the hidden protagonism of women in the criminal proceedings from rural Spain calls for us to develop a more precise understanding of local legal cultures, and more supple ways of identifying women's non-written actions in the legal sphere, whether the petitioners were rural or urban, indigenous or Spanish. Throughout the century, even those women who had access to formal channels of law or were in closest proximity to “Spanish” legal culture—whether women in Spain or creole women in colonial cities—engaged in a host of actions against their husbands and lovers that called on the legitimizing power of the judicial sphere but were not recorded in writing. “Legal agency,” then, must be defined in a way that recognizes the importance of formal written petitions issued in the name of women but is not reduced to their production.

Spanish historian Tomás Mantecón-Movellán has utilized the concept of “infrajustice” in a manner that can help us conceptualize the fluidity between women's unwritten appeals to authorities to solve domestic disputes and the formal act of suing a man.Footnote 54 For Mantecón, infrajusticialidad describes how rural people in early modern Cantabria only hesitantly invited legal intervention from officials from beyond the community in local, often domestic disputes. They preferred to resolve issues locally by relying on social codes of public esteem and relatively rigid, gendered normative prescriptions. In this formulation, the operational distinction is not between “extralegal” and “legal” activity, which would imply that actions were either illegitimate or legitimate by virtue of being unwritten or written. Rather, written and verbal appeals operated in overlapping fields in which “local custom”—which he terms an “ambit of justice beyond the courtroom”—competed with official intrusions by legal representatives of a modernizing absolutist state.

Mantecón's concept of infrajusticialidad beautifully describes justice in the Montes de Toledo and captures something of the prevalence of verbal complaints in the rural regions populated by native communities such as Oaxaca and Trujillo. We can further extend the concept to help us understand gendered justice in the cities as well, where the extralegal and the legal, the verbal and the written, and the “community” and the “court,” flowed into and out of one another constantly.

After all, in the cities of the Spanish empire legal bureaucrats were not always abstract, “outside” figures hermetically ensconced in imposing buildings. As Tamar Herzog writes of Quito's criminal cases in the era preceding the Bourbon years, justice was “never impartial, never distanced from society.”Footnote 55 Royal and Church legal “administration” spilled outside of tribunals into the city's streets, taverns, and pews. In Mexico City, Lima, or even Oaxaca City, it was easy enough to bump into court personnel and bend their ear about an outstanding debt one was owed, or to gossip about the flirtatious actress who had recently come to town. In the cities, judges received litigants in the antechambers of their homes as well as in the courtrooms, and it was perfectly possible for a humble woman such as the mixed-race (parda) Segunda Montejo to personally approach a powerful man such as the bishop of Trujillo, Jaime Baltásar Martínez de Campañón, after having fled barefoot from her husband's blows at home.Footnote 56

Employed in this way, the concept of infrajusticialidad reminds us that lawsuits could be something other than inaugural texts, and that they came with histories of their own. It also permits us to better trace the fluidity in both the meaning and location of “justice” in Spain and its American colonies, to illuminate the space between the judicial and the extra-judicial, and to grasp the dynamic interaction between the verbal and the written.

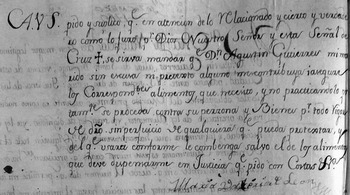

Figure 1 Doña María Valeria León signs her name, with a splotch, at the end of the neatly handwritten opening petition in her divorce suit. The text of the motion was penned by a scribe or her procurador but was written in the first person. Archivo Arzobispal de Lima, Divorcios, Leg. 75, León versus Valencia, 1789, 1 v.

For a final word (as it were) on the fluidity between women's “extrajudicial” and “judicial” legal actions, consider the definition of “pleito” in eighteenth-century Spanish. A period dictionary gives meanings ranging from “war,” to “litigation,” to a “domestic dispute” (“riña o qüestion casera”).Footnote 57 When the word pleito was employed in lawsuits, as it was from time to time in Mexico, it was just as multivalent. It might refer to a domestic dispute alone, or it might signal that a dispute had developed somewhere on a continuum between the home and the court. In the latter usage, it conveyed something slightly more official than simply a dispute, more “legal” in a strict sense of the word. A “pleito de voces” could mean a loud argument between lovers or spouses, but it also could indicate that a judicial authority—a secular judicial authority, to be specific—had verbally been called into the dispute.Footnote 58 In the eighteenth-century Spanish empire, a pleito—a suit—flowed in and out of the home, the community, and the court.

Figure 2 Claudio Linati's 1827 rendering of a Mexico City public scribe, whom he describes as holding all of the secrets of the country. “Escribano público” reproduced in Trajes Civiles, militares y religiosos de México (Distrito Federal: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Aútonoma de México, 1956), pl. 9.

Goals

Steve Stern, in a study of gender and violence in late colonial Mexico, demonstrates that women of all classes and castes engaged in a strategy that he terms “pluralizing patriarchs,” moving up chains of male community and administrative authorities in order to restrain violent husbands or lovers. Yet, because Stern does not distinguish criminal cases in which women were registered as accusers or litigants from cases initiated by judges de oficio, his observations about the pluralization strategy collapse distinct types of authority into a single category of “patriarchs.” This leaves untouched the question of what inspired women—rather than colonial officials—to turn verbal complaints into formal texts presented as lawsuits.Footnote 59

Of course, histories of gender in the Spanish empire are full of explanations for women's civil suits against husbands and descriptions of the crimes for which women brought charges. An especially vast literature on divorce points to women's reasons for seeking separation from husbands, ranging from the canonically valid legal criterion of mistreatment, abandonment, and adultery to more cultural factors, including a lack of love or affection.Footnote 60 Other scholars take the analysis a step further and situate women's legal motives within broader historical economic or political contexts: women filed divorce charges to gain material control over property, to politically “equalize” with men or challenge patriarchal hierarchies, or because their gender limited their ability to simply leave a bad marriage.Footnote 61

The stacks of books and articles written on divorce in colonial Latin America tend to repeat what women and their legal representatives reported about women's desire to live separately from their husbands. But they do not settle the question of why women decided to seek official divorces. The distinction is a matter of more than semantics. Take as an example Doña Rosa de los Angeles, who married in 1728. Only days after she walked down the aisle it became clear that she had made a bad match, so she lived separated from her husband for nineteen years, before filing for divorce in the Church tribunals of Trujillo.Footnote 62 Doña Rosa's opening petition contains a litany of reasons that the marriage was doomed from the start—her mother had forced her to marry; her husband was abusive—but it does not explain what had prompted her to seek divorce after so many years.

After all, as the prior section has shown, regardless of class, caste, or location, women did not necessarily have to file lawsuits or formal criminal charges against husbands and lovers to achieve outcomes that they considered to be “justice.” Without marking a single piece of paper, a woman could marshal the aid of a community or even an authority figure to help her force a husband or lover to break up with a girlfriend, return home, or stop beating her. In doing so, she could even cross firmly into a “judicial” sphere, since the entities to which women appealed held the power—and many even the legal authority—to imprison or fine a man en lo extrajudicial.Footnote 63

Recognizing that written suits were not the only possible sites of “justice” in the eighteenth-century empire makes notable some of the suits women filed at the end of the century. During its last decades, the types of petitions that women presented to the courts, and the outcomes they sought, cleaved into two categories, one “traditional,” and one new. Traditional petitions, representing but one phase in an infrajusticial process, were often intended to achieve a rapid outcome. In the newer type of petition, which became more common at the century's end, the suit was no longer an incidental, final recourse but rather an early, purposeful action. Women used their petitions to open larger suits or to justify their right to sue in the first place.

Traditional women's petitions, filed throughout the century, might be viewed as one link in a long chain of attempts to restrain men's behavior or elicit punishment. This explains why a significant number of women, and sometimes men, dropped marriage or criminal suits mid-process, at times openly confessing that they had only sued in order to prompt their spouse to return to them or stop an affair. Once they had accomplished this they no longer needed official intervention.Footnote 64

In some suits, then, even “judicial” action entailed short-term engagement with the courts and often only incidentally produced written documentation. To further illustrate this, let us return to Felipa Huesca from Xicochamilco. Had she achieved her goals when she went first to her pueblo's priest to complain about her husband's sale of her cows, no ink would have been spilled over her affairs. We can gain a deeper understanding of what motivated Felipa's suit and how it fit into her prior legal efforts if we consider the final words of her auto. This was the standard, formulaic location where litigants made clear what they were requesting from judges. Her statement, in a mix of the first- and third-person phrasing common in legal petitions, says that she petitioned the viceroy “to pursue the case, and asks not to divorce since there is law for that (hai ley pa eyo),” but rather that, “Your Excellency orders that they send [her husband] to a presidio and that he declare to whom he sold my cows so that the buyers can pay me.”Footnote 65

Felipa's petition announced that she wished to “pursue her case,” though she clearly did not wish to live with her husband and wanted to control her own property. Yet she distinguished her legal action from a divorce suit. For her, there was a suit and there was her petition. The concrete, limited nature of her demands meant that, rather than opening a civil or criminal case in which her husband would be notified of her complaint and permitted the opportunity to respond in writing, the issue could be handled summarily and without formalizing litigation. This is exactly what happened. After the viceroy requested information from the subdelegado of Jalapa, his advisor, the asesor general, decided there were no grounds for formal litigation, but he counseled the viceroy, “Your Excellency can, if you see fit, order that she be given to understand the report so that she can appear before the sub-delegate to demand … justice without giving grounds for any [future] complaints.”Footnote 66

In its pre-history of judicial intervention, Felipa's petition is similar to the opening statement in a civil case brought by Doña Petra Guadalupe de la Cal, in 1794, but the similarities end there. Doña Petra's petition began with a saga of her attempts to get her husband to come back home after he had taken up with a “woman of the lower sphere.” She had begun by trying to persuade him on her own, first with words, then by moving with him from the city of Puebla to the village of Atlixco, hoping that the distance would break up the affair. After he beat her, she filed a criminal abuse complaint with the intendant, a high-level district magistrate. She also took a separate civil suit to the village justices of Atlixco over her financial support and his affair. She finally convinced one of the village alcaldes to send her written petition on to the sub-delegate of Puebla. But when the sub-delegate failed to grant her request for a suit, she went to the city herself, where, she reported, “the señor intendente and his asesor told me not to bother them.”Footnote 67 Since she no longer possessed all of the papers generated by her attempts to seek justice, compiled in a dossier called “los autos,” she then moved to Mexico City in order to take her case to the viceroy.

As her petition led into her formal request for action by the viceroy, Doña Petra veered sharply from the path charted by the indigenous woman Felipa:

How many times I have complained, and how many times more [have I remained in] silence, as much for the integrity of the court filings [estar constante los autos] as in order not to disturb the attention of Your Excellency, to whom I submissively plead not that you punish my husband and his lover; but instead that you make the necessary rulings, so that I, having already suffered so much injustice, might have some quiet in my conscience and that my husband might sustain me, giving me and my little ones what is necessary; and if this means I must present myself before the ecclesiastical [tribunal] to file for divorce, I am prepared to do so; but so that Your Excellency might proceed according to law, may it dignify you to order that the intendant turn over my autos in the return mail without delay.Footnote 68

Felipa and Doña Petra approached the instruments and process of justice in very different ways. Felipa stayed home and sent her petition to the capital city; Doña Petra made the capital her home in order to bring suit. In Felipa's petition, divorce (which was tantamount to a “suit”) was not an alternative. Her justice could be achieved outside the processes of formal justice by punishing her husband and obtaining her money. For Doña Petra, justice was located inside the processes of law, and she conceived of her civil suit as analogous to a divorce—her petition was not a simple request for action but the initiation of a suit proper to secular jurisdiction. Her autos, as an accumulated artifact of her attempts to seek justice, held a value separate from her personal appeal to the viceroy. She in fact stated that she had avoided contact with the minister of justice in order to preserve the integrity of the suit, which was dissociated from the substance of her individual requests. Preferring all matters to take place within the court system and in writing, she would later complain that her husband was passing “sinister” extrajudicial information to the intendant in the case.

For women like Doña Petra, the infrajusticial world of the seventeenth century and first half of the eighteenth, in which “justice was never impartial, never distanced from society,” had begun to recede. In her suit, we see the construction of a partition—however partial and potentially surmountable—between the judicial and the extrajudicial, between the solidity of written autos and the more inconstant, corruptible world of verbal intervention and information. For Doña Petra, litigation against her husband was about more than simply receiving alimony or punishing her husband for his infidelity; her opening petition was about her right to sue and to have the suit recorded.

Cases like Doña Petra's did not replace traditional “infrajusticial” petitions but rather assumed a place beside them. They were no doubt spurred on by the changing jurisdictional policies of the Spanish Bourbon kings. In the late eighteenth century, Spanish kings issued a series of edicts favoring secular courts as the privileged tribunals for several matters related to marriage, including alimony suits and adultery, bigamy, and dowry cases.Footnote 69 It was against this backdrop that women's opening petitions, as well as their maneuverings within the cases that followed, increasingly began to conjure concepts of a basic right to have their cases litigated to judgment, especially in secular courts, rather than resolved informally. At the same time, formal litigation increasingly became, if not always a first resort, a more immediate one. In the openings of some petitions, which before had usually contained a narration of a woman's prior visits to judges or other authority figures, there were now only vague claims that a woman had by herself attempted to persuade a husband to act differently, sometimes through letters, sometimes through words.Footnote 70 Sometimes there was no pre-history at all.

Take, for example, the case of Rita de Palacios, a hardworking woman from Santiago de Cao, just outside Trujillo, who from her job as a maid in a monastery had saved enough money to buy some slaves.Footnote 71 Rita narrated no prior attempt to reconcile with her husband when she appeared before the corregidor of Trujillo with a simple request: that he prevent her husband from leaving for Lima, where he planned to free one of the slaves she had purchased, a woman with whom her husband tacitly admitted having an ongoing sexual relationship. After the corregidor threw her husband in jail for adultery, Rita decided to continue with a formal suit for the return of her slave. In response, her husband contracted a lawyer, who rejected the notion that Rita had a right to undertake any legal action at all against his client.

“That Rita's litigation and way of proceeding is baseless is obvious at first glance,” the lawyer argued. “What she claims as a right [that is, her right to litigate] is far from it.” Rita, who was never assigned an attorney and always filed petitions that bore only her signature, pointed out in her response, “It is well known that the plaintiff can put forward a demand in the extraordinary and summary mode when it is between a husband and wife, and that it is not necessary to follow the stations of the law.” However, her petition continued, “I have found myself forced to submit a formal case,” which “would not be resolved” even if they were to patch up their marriage. Thus, for Rita, the right to see her case against her husband through to the end was independent from the status of their marriage.

As more women like Rita brought cases against husbands and lovers that sought not only a favorable outcome but also their “day in court,” some marital reunions took place as written, secular affairs rather than unrecorded, religious reconciliations. In fact, the women who sought written resolutions to domestic conflicts—women who in the colonies were increasingly of humble means and non-white—exploited the politics of royal encroachment on matters of the hearth.Footnote 72 Some began to treat reconciliations as expressly secular legal opportunities to formally and contractually force their husbands into new behaviors.

A truly stunning example of the new, contractual state of the reunion comes from southern Spain, where in 1776 María del Carmen Barrena threatened to divorce her young, unemployed husband because he was burning through her dowry.Footnote 73 After taking her case to not only the ecclesiastical courts but also her local corregidor, and then to the region's high court, the Audiencia of Granada, María del Carmen eventually decided to reconcile with her husband, but only if he agreed to renounce all the rights over her property and person that he enjoyed as a married man. The contract she had drawn up, consisting of twelve individual points, stipulated that her husband would, among other things, be stripped of the ability to administer her dowry, grant a blanket license for her to appear in court, and renounce his right to force her to live with him.

The records of one corregidor in Mexico City also hint at how marital reunions, increasingly taking place in the secular sphere, had at the end of the 1700s begun to take on a contractual character. Women's complaints, which he formerly might have handled summarily, now were documented in formal, but abbreviated criminal cases.Footnote 74 In the records, the corregidor showed himself quite determined to reunite quarrelling couples. But, in these new quasi-formal secular suits, the corregidor solicited specific promises from men as pre-conditions for reunions, including in one case a pledge to provide financial support in the same manner in which a separated woman might receive alimony.Footnote 75

Perhaps, then, it was a sign of the times that, even though she did not seek a divorce, the indigenous woman Tomasa Maldonado included a request for a daily stipend (diario), or alimony payments, in her opening petition to the intendant of Lima in 1796. In fact, the judge who heard her case found it difficult to determine exactly what the suit was about. She initially complained that her husband Manuel was spending up the “fruits of her labor” (granjerías), but by the time her case had moved from her coastal pueblo of Lurín to Lima, it had become about much more.

When Tomasa separated from Manuel, she did not even bother to complain to Lurín's alcaldes about his financial and sexual profligacy. After all, they were all friends of his and she was convinced she would find no justice at home. So she went to the corregidor, an act that, her petition reported, only prompted Manuel to pull her hair and take from her the key to her safe, cutting her off from any resources she might use to pay for the suit. She sent a petition to Lima, which was heard by the sub-delegate, requesting that Manuel return the key and be prohibited from visiting his lover's house. Manuel counter-sued, charging that Tomasa had secretly entered their home through the roof to break into the safe, and then absconded to Lima with a bag of silver stashed under her hat, which she intended to spend in pursuit of her case against him. Later, he said, she returned to Lurín with a piece of paper that she claimed contained an order for his arrest. The case record shows no evidence that any judicial authority had issued such an order, but Manuel could not immediately know this since neither he nor Tomasa could read.

The sub-delegate tried to rush the case to conclusion, but he probably should have realized that what Tomasa was after was not marital reconciliation but litigation. When she won one small victory, she would petition again for another; if an order was not promptly carried out, she would petition again. Finally, she decided to go over the sub-delegate's head to the viceroy and demanded that a court scribe certify all of the autos, or individual actions, that had accumulated in the sub-delegate's tribunal. The sub-delegate perceived the appeal—made by a provincial Indian woman based on what he called “frivolous legal points”—as an insult to his honor (hombría de bien). He refused the jurisdictional challenge, and pursued the case all the way to the Spanish king in an effort to keep the autos out of her hands.Footnote 76

As outraged as the sub-delegate of Lima was, he might also have been puzzled by Tomasa's tenacity. After all, he had conceded that she could not receive a fair hearing from justices in her pueblo, he had admitted her complaint, and he had complied with many of her requests. Still she seemed unsatisfied. It was as if she did not want a resolution, but simply wanted to sue and, as she sued, to have control over the material fact of the suit. It must have seemed to the judge that she simply wanted to be a litigant.

Conclusion

This article has shifted attention away from petitions-as-narratives, experimenting with a method that focuses less on what women's opening petitions said and more on what they did. Asking what petitions did has meant, first, tracing the histories that preceded the materialization of complaints as written documents presented before magistrates, and today housed in archives of Spain and Spanish America. For many petitions, this produced a genealogy of prior actions with priests, elders, and judges who acted not only as community authorities but also as judicial authorities, even when no papers were drawn up in the case. Tracing the pre-histories of the petitions has also involved paying statistical homage to notable differences in the demographics and regional, chronological, and jurisdictional locations of women's suits. That is, I have tried to illuminate where and when certain kinds of petitions occurred. It is clear that all women in the empire possessed the ability to enlist a judge in their disputes with husbands or lovers. But women in the cities, particularly the colonial cities, had a greater propensity to turn such enlistments into written suits.

Asking what petitions did meant, next, looking at women's goals in filing them. More specifically, I have endeavored to locate the goals of the petition on a grid of multiple legal possibilities, including some options that could take place outside of the realm of writing and some that could not. A petition could be a mere written version of an appeal that might just as easily have transpired verbally. It could be a threat to sue or a tentative step toward more litigation in order to force a non-judicial outcome. Or, it could be the beginning of a suit. Many times it was something in between.

This in-between condition, which I have described with reference to the concept of “infrajusticialidad,” suggests that historians of gender might conceptualize the Spanish imperial legal system in less static terms than are implied by the “codes” and “structure” models with which we normally work. In place of seeing the law as a solid “structure”—a labyrinth of “Western” legalese and paperwork that entrapped women with its gendered languages and logic—we should approach it as a dynamic space into which women could enter and then retreat. When Felipa Huesca distinguished her formal, written petition to the highest judicial authority in Mexico from the practice of “law” (lei), she stepped into this dynamic space of justice.

Finally, my examination of female petitions has revealed that in the late eighteenth century the dynamic space of the law became host to a growing notion of the “legal” as formal, written, and increasingly secular practice. The petition came to represent both the inauguration of and the declaration of the legitimacy of a woman's lawsuit, as well as her status as a litigant. For some women who sought justice in the final decades of the century, infrajusticidalidad, in which verbal exchanges and the written word intermingled, became too nebulous a process. Particularly so for the middling-class women in colonial cities who capitalized on the expansion of secular royal jurisdiction by attempting to formalize suits against husbands, or by stipulating, sometimes in writing, ongoing contractual demands as preconditions for their return to the hearth.

As these women approached the courts seeking formal acceptance of a case that would be brought to judgment, the written records of litigation served a purpose quite distinct from petitions in which a woman sought a discrete official action. Crucially, this purpose was prior to and distinct from whatever sentence a judge would eventually render. The initial acceptance of a request for a formal process against a husband for divorce, adultery, abandonment, or alimony signified that legal actions would continue and that the woman's status as a legal subject would endure at least until a judgment was handed down, and often beyond, as settlements were made. These actions would become tangible as physical artifact as the papers expanded from a loose sheet containing a demanda into a substantial legajo, or file.

Individually, the separate autos in a suit—the petitions, testimony, notary records, and interim judgments—were pieces of evidence that could contradict and overrule one another. But at the end of the eighteenth century, the autos in women's suits against husbands or lovers collectively took on a legitimating value of their own, a value and force that existed independently of the legal agents who authored the pages and the judges who authorized the suits. The written documents that accumulated after an initial petition was filed became a physical manifestation of women's very subjectivity as legal agents. For these women, the petition was no longer one event in a longer judicial process; it was the judicial process. For them, there could no longer be justice before the suit, or judicial subjectivity before anything but the law.