Background

The Phlaegrean coast near Naples, Italy, has been formed by a series of geological events and the continual uplift and subsidence of the land. Volcanic activity has not only shaped the landscape but also preserved rich archaeological evidence beneath the current sea level.

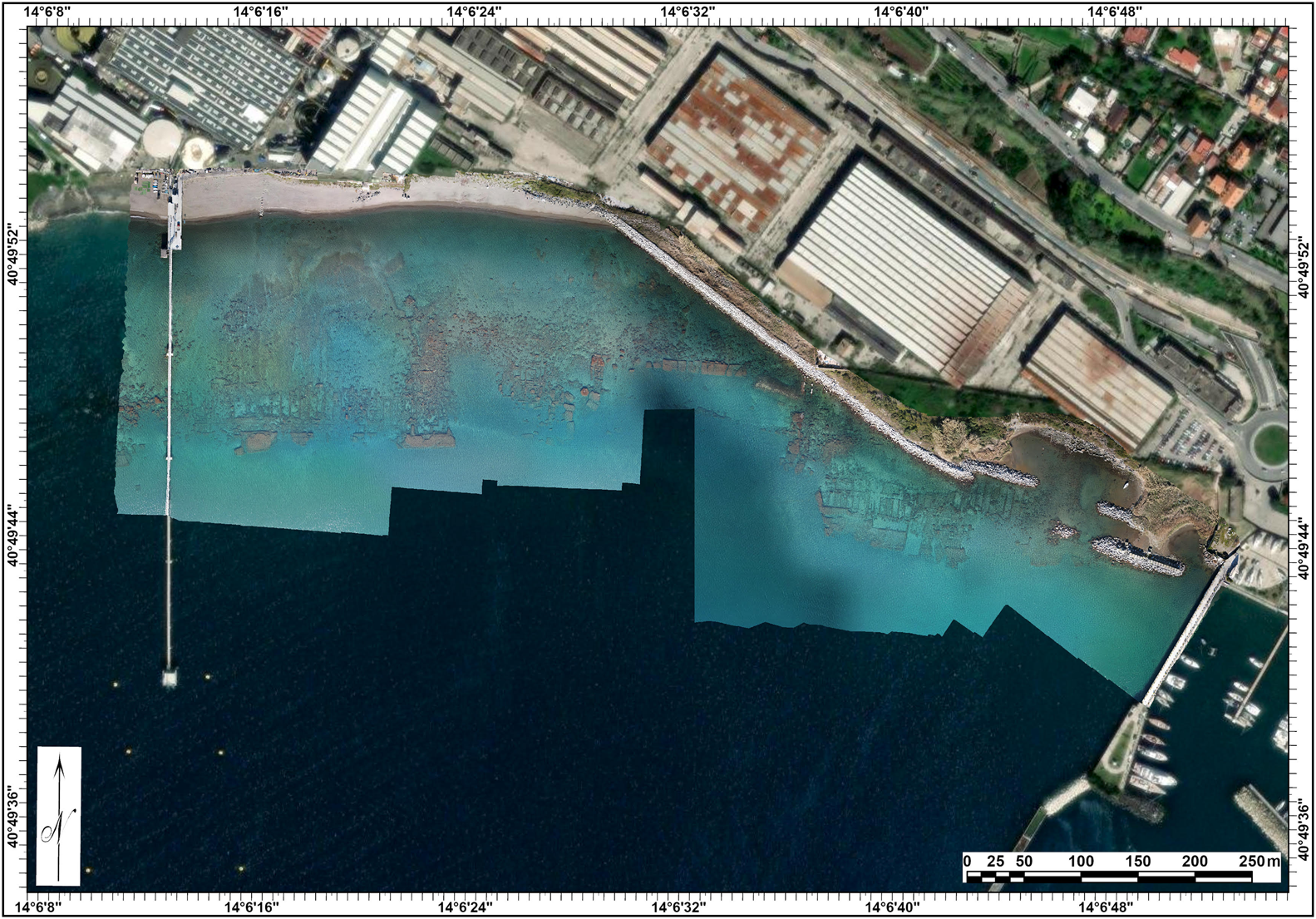

The ripa Puteolana—a 2km expanse of submerged Roman districts between the port of Puteoli and the Portus Julius—is just one component of a much larger system that stretches across the entire Gulf of Pozzuoli. Particularly during the Augustan era (31 BC–AD 14), it was a prime example of urban planning and architectural development in a bustling port district with a pivotal role in maritime trade, primarily in grain distribution. Consequently, the coastline was predominantly occupied by warehouses for the storage of goods (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Submerged warehouses in the ripa Puteolana (figure by M. Stefanile).

Puteoli's central role in complex mercantile networks is also evident in the layout of storage facilities. The oldest, from the second to first centuries BC, are located in Rione Terra, while newer ones dating from the Augustan era are placed throughout the city near the port and key roadways.

The project Between Land and Sea (a collaboration between the Ministry of Culture and the University of Campania, with the involvement of the Scuola Superiore Meridionale for underwater areas, see Stefanile et al. Reference Stefanile, Silani, Tardugno and Capaldi2023) conducted new underwater research along the ripa Puteolana in the port of Puteoli (Figure 2). It discovered a submerged Nabataean temple—the only one currently known outside of Nabataea (situated between the Arabian and Sinai Peninsulas).

Figure 2. Orthophoto of the ripa Puteolana (figure by M. Silani).

Reconstructing the architecture of the temple

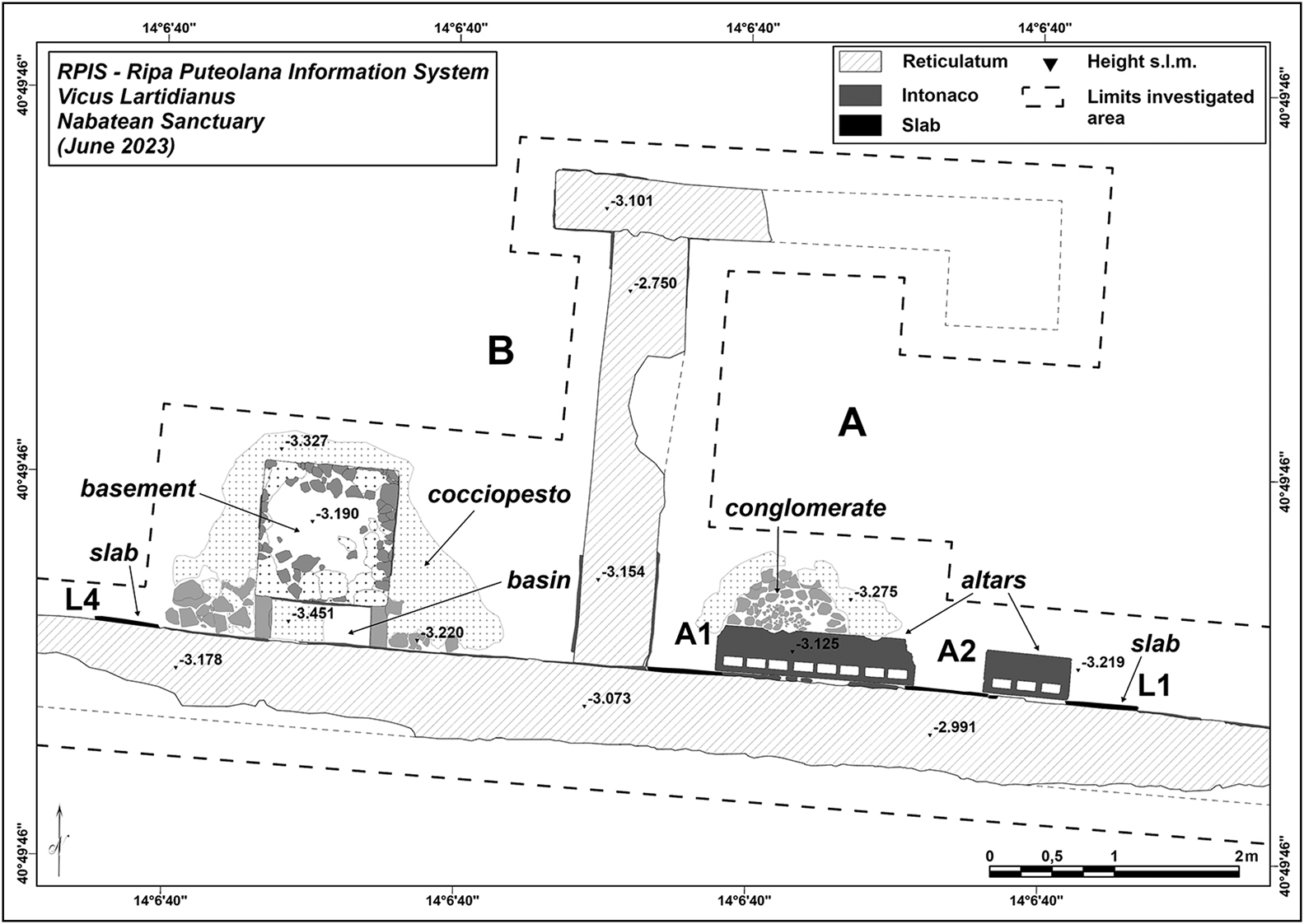

Underwater explorations carried out in 2023—in areas identified from a photogrammetric aerial plan of the ripa Puteolana compiled in 2022—located the sanctuary. At the current research stage, two rooms (A and B), delimited by opus reticulatum walls, have been identified and documented with a photogrammetric survey (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Plan of the Nabataean temple excavated to date (figure by M. Silani).

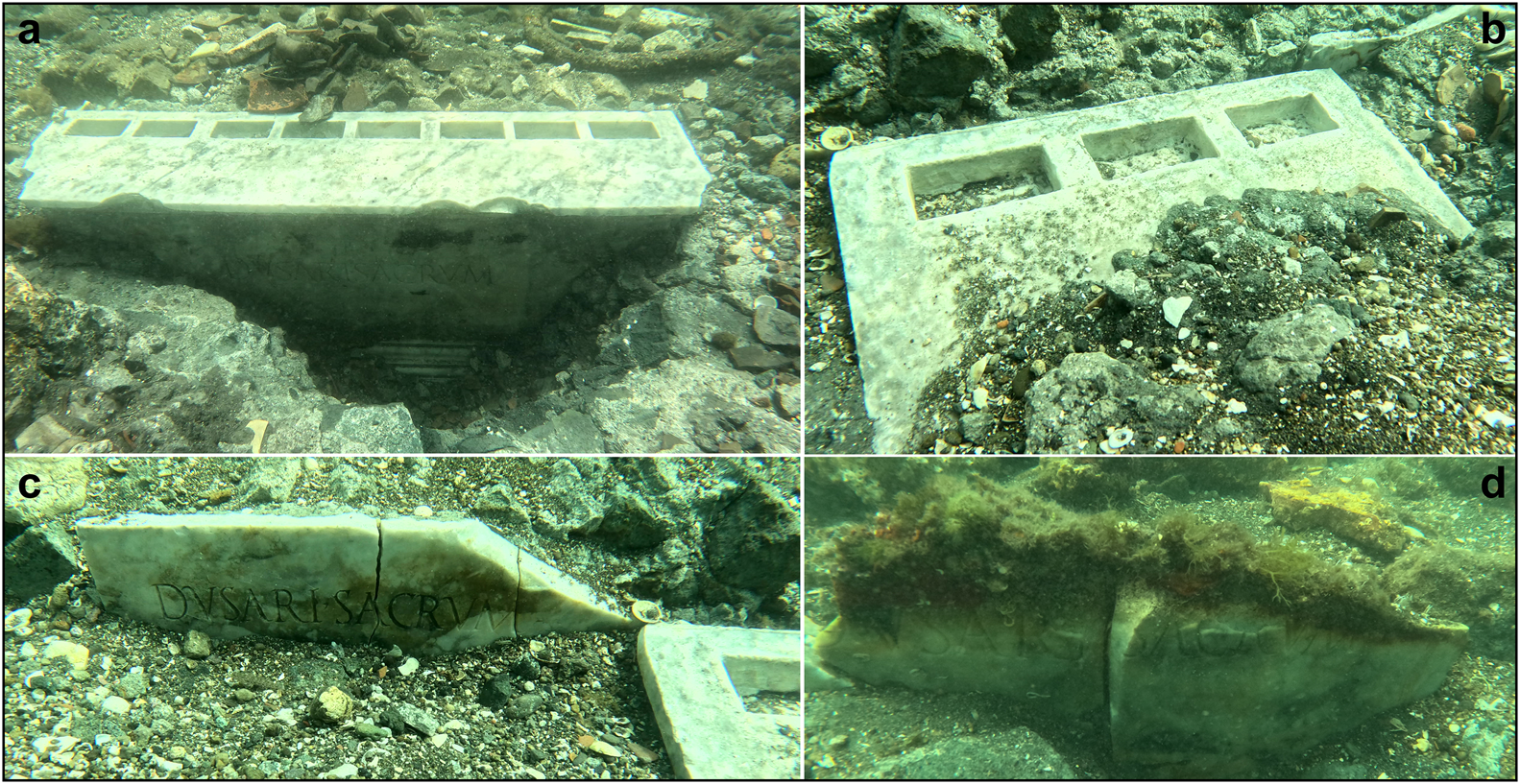

In room A, two altars made of white Luni marble are still in situ, leaning against the southern perimeter wall. Altar A1 is largest (1.6 × 0.38 × 0.65m); it has a mensa with eight rectangular recesses (150 × 70 × 45mm) probably for housing aniconic betils (similar to the big altar at the Museum of Baia (Lacerenza Reference Lacerenza1988–1989)) and the dedicatory inscription Dusari sacrum on the front (Figure 4a). Altar A2 (0.69 × 0.34 × (?)m) has only three rectangular recesses (150 × 70 × 45mm) (Figure 4b). On either side of the two altars, the southern perimeter wall is covered with white marble. Slab L1 (600 × 30 × (?)mm; Figure 4c), east of altar A2, is inscribed with the dedication Dusari sacrum. In room B, approximately 3.35m from the dividing wall of the two rooms, the southern perimeter wall also has a white marble slab covering, where slab L4 (550 × 30 × (?)mm (Figure 4d) also shows the inscription Dusari sacrum.

Figure 4. Nabataean temple: a) altar A1; b) altar A2; c) slab L1; d) slab L4 (figure by M. Stefanile).

Near the south-eastern corner of room B, the remains of a concrete block (1.1 × 1.1m) in opus reticulatum covered with plaster are visible, located 1.5m from the dividing wall of rooms A and B and 0.3m from the southern perimeter wall. It is currently not possible to define the function of this plinth. In a second phase of the building's life, a cocciopesto-covered basin (0.8 × 0.3 × 0.2m) was installed between the south side of the plinth and the southern perimeter wall. At the same time, on the sides of the plinth, a cocciopesto floor was built on top of a conglomerate that also encased and sealed the altars of room A, rich in ceramic inclusions.

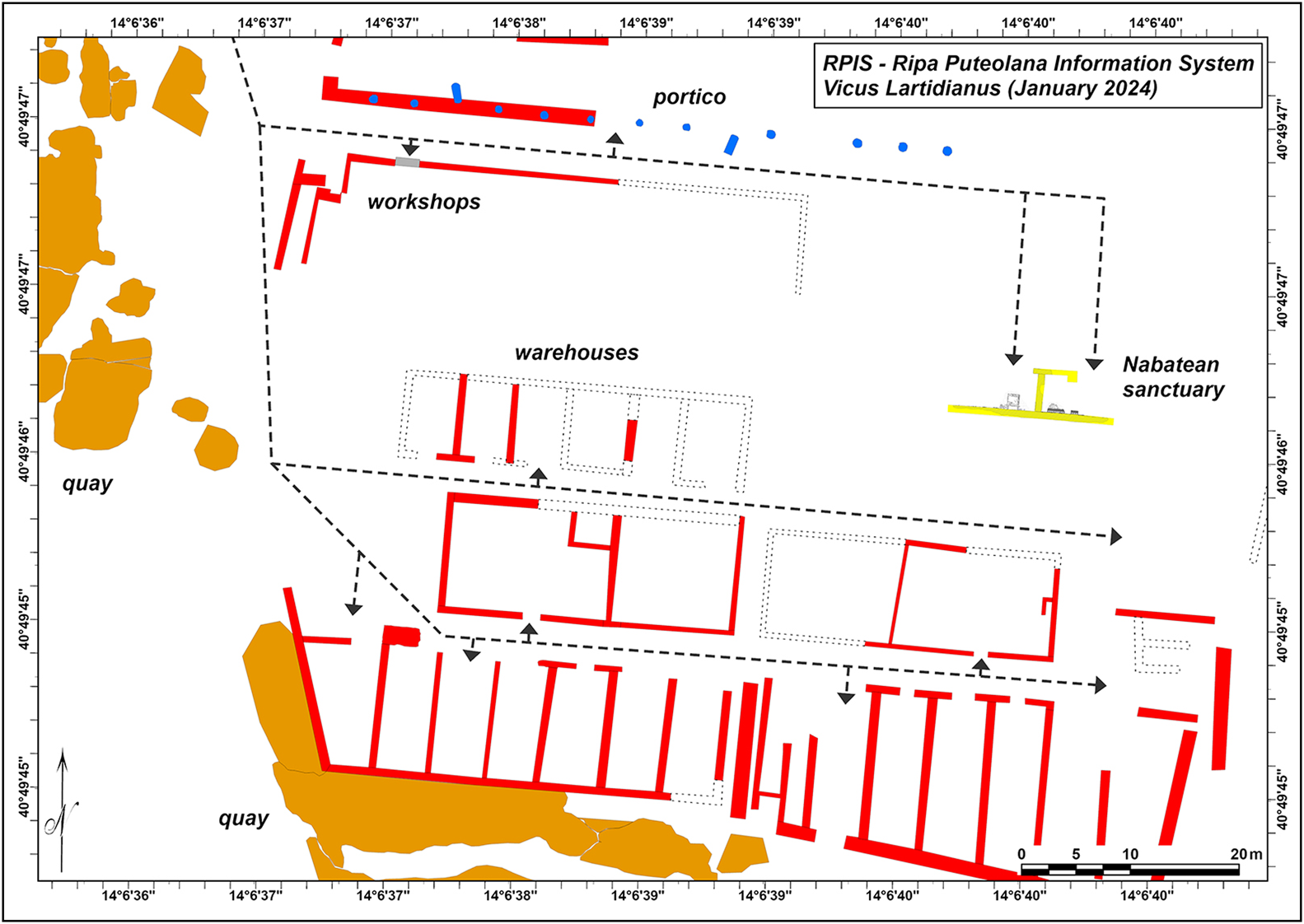

The research carried out so far at the Nabataean temple allows us to envisage a building with a rectangular plan and two rooms with access facing north, linked to the internal routes of the vicus Lartidianus (Figure 5). The layout of the roof cannot be established with certainty, whereas the presence of the altars in room A could also suggest a roofless sacellum.

Figure 5. The Nabataean temple and the internal routes of the vicus Lartidianus (dotted lines) at the current stage of research (figure by M. Silani).

Research planned for 2024 and further underwater excavation of the temple might lead to full understanding of the building and its story.

Life and death of a community of merchants

The existence of a Nabataean sanctuary within the port area confirms that there was a community from that region participating in the commercial activities of Puteoli (Camodeca Reference Camodeca2018). The integration of these individuals within the local community is evident in the building techniques and materials used in the construction of the temple, and for the choice of Latin for the inscriptions to their supreme god, the lord of the mountains and the germinating force of nature, Dushara. Clearly, the use of local materials and techniques, consistent with the rest of the area, is easily explained by the abundance of tuff and pozzolana in the surroundings of the site and by the use of local workers. The use of Luni marble for the inscribed slabs, for the altars and for part of the wall coverings, can be linked with the availability of marbles in Puteoli and with the full integration of the rich Nabataean merchants in the Augustan tradition. The shape and decoration of the altars are typically Augustan and Roman; only the holes for the insertion of the betils betray the distant origins of the dedicatees. Considering the inscriptions, the Nabataeans of Puteoli chose a simple Latin text in a typical Augustan style, intending to honour their god but, above all, to communicate with Romans and peregrini united by the use of Latin. The temple was a place of worship, a refuge for foreigners and especially a place of exchange, business and trade under the guarantee, control and authority of the god Dusares.

The edification of the sanctuary was possible when the Nabataeans enjoyed the freedom and opportunities offered by the friendship with Rome and the independence of their motherland. In this golden age, from the time of Augustus to that of Trajan (AD 98–117), the Nabataeans accumulated an enormous wealth, fully entering the Mediterranean trade with the control of the traffic of Eastern luxury goods, from the Indian Ocean, along the caravan routes of the desert, up to the port of Gaza and towards Rome, probably through Alexandria, certainly through Puteoli.

At the time of Trajan, this situation suddenly changed and the creation of the province of Arabia Petraea had severe consequences: while Rome imposed its authority and its laws, also the trade routes were absorbed into a general network controlled by the State, with very little space for the initiatives of a people no longer independent. The downsizing of Nabataeans’ trade and the end of their small monopoly are perhaps the simplest explanations for the end of the sanctuary; probably at the beginning of the second century AD it was filled with concrete, without any iconoclastic intent and with the typical superstitious respect of Rome towards consecrated places. The removal or destruction of the sacra of Dusares would usually have required complicated rites of desacralisation but, in this case, the temple was just filled in and a new walking surface was built above it; the area was too central and strategic to remain abandoned for a long time. The materials found in the filling stratigraphy, with Dressel 2–4 amphorae on the bottom, and no material later than the end of the first century AD, confirm obliteration of the site following the creation of the province of Arabia in 106 AD. That was, apparently, the end of the Nabataeans in Puteoli.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to express their gratitude to all the people who offered precious support for this research and especially to M. Nuzzo, T.E. Cinquantaquattro, C. Rescigno, G. Camodeca and P. Arnaud.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.