While previously unthinkable, the prospect of the People's Liberation Army (PLA) prevailing in a cross-Strait contingency has become an increasing possibility in the wake of decades of military reforms and modernization.Footnote 1 However, given the extreme risks of an amphibious invasion and the likely strategic setbacks to its grander geostrategic ambitions (even if China were to triumph in an armed conflict), the prospect of “winning without fighting” still retains a strong allure for Beijing. For this reason, it is surprising that cross-Strait lawfare remains an under-researched, analytical blind-spot, as Anglophone scholarship has hitherto almost exclusively focused on lawfare through the prism of Beijing's instrumental use of legal tools at the theatre level to advance its claims in the South China Sea.Footnote 2

In this article, we argue that from its origins as one of the pillars of China's comprehensive non-kinetic “three warfares” (san zhan 三战) concept, legal warfare or Chinese “lawfare” has evolved into a central component of Beijing's broader hybrid strategy, definable as “hybrid influencing,” in which legal tools are leveraged in concert with a wider array of measures that range from economic statecraft and diplomatic manoeuvring to military signalling and information operations to coerce the self-ruled island towards “reunification” (tongyi 统一).Footnote 3 In this way, by providing a counterpoint to hyperbolic speculation about the timing and likelihood of a full-scale invasion by “little blue men,” this detailed case study sheds empirical light on a hybrid strategy that over the long term might be more likely to secure Beijing's goals with respect to Taiwan. Moreover, as Taiwan is situated on the frontline of the intensifying contestation between liberal democracies and techno-authoritarian states, our findings may have broader implications for understanding the longer-range systemic dynamics inherent to this new era of great power competition.

Over the course of two decades of cross-Strait relations, stretching from the confrontations of the Chen Shui-bian 陳水扁 era (2000–2008), to the cross-Strait rapprochement that characterized the Ma Ying-jeou 馬英九 presidency (2008–2016), and finally to the collapse of relations between the two sides in first term of the Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文 administration (2016–2024), research on China's “reunification” operations has generally privileged frames such as “united front work” (tongzhan gongzuo 统战工作),Footnote 4 “weaponized interdependence,”Footnote 5 “political warfare”Footnote 6 and “sharp power”Footnote 7 to research Chinese “reunification” operations. These tools possess analytical usefulness in relation to specific tactical manoeuvres such as the infiltration of Taiwan's socioeconomic fabric, or the unrelenting use of economic statecraft against sectors of the island's economy to fashion local electoral preferences. Nonetheless, we contend that such conceptual devices de-emphasize the cross-domain linkages of Chinese “reunification” operations, especially across a more strategic horizon, including peacetime, in regard to the legal domain within cross-Strait relations. Furthermore, they do not tell us enough about the instrumental logic behind the tempo of such cross-domain operations.

In contrast, research examining Chinese operations targeted at Taiwan in terms of “grey zones” has had the merit to put the legal domain back in the spotlight, with a primary focus on maritime territorial contestations.Footnote 8 However, by definition, successful grey zone strategies exploit the interstices between peace and war in a kind of high-end game of chicken, thereby excluding the possibility of escalation to the level of an armed conflict. An attempt to inductively plug this gap in the application of theory to the case of Taiwan explains a string of commentaries employing a distinct conceptualization of the hybrid domain, that of “hybrid warfare,” to discuss “reunification” operations.Footnote 9 This notion, however, fails to encompass the full bandwidth of Beijing's strategy. While “hybrid” in its combination of methods and tools to achieve the goal of “reunification,” China's Taiwan strategy transcends operations immediately ascribable to the perimeter of “warfare” by including influence operations informed by Leninist conceptions of propaganda, as well as localized understandings of “soft power” and the use of economic statecraft to establish “sticky power” dynamics with Taiwanese actors.Footnote 10 Moreover, the increasingly popular term, “hybrid warfare,” features a conceptual tension between its use as “a form or mode of warfare” and its common application as “part of a strategy.”Footnote 11 This tension implies the presence of a “kinetic threshold” and thus enables conceptualization of a “sub-kinetic” level of conflict coexisting with the real possibility of escalation to a shooting war, which would fit current Chinese reunification operations towards Taiwan conducted at a strategic level during peacetime.

Against this backdrop, we argue that Aapo Cederberg and colleagues’ concept of “hybrid influencing,” coined by a joint NATO–European Union research collaboration, solves this analytical tension and provides the most appropriate framework for examining Chinese “reunification” operations.Footnote 12 Hybrid influencing is defined as the orchestrated execution of “two or more activities” across the target's DIMEFIL domain, which covers diplomacy, intelligence, military, economy, finance, infrastructure and law, in order to advance a hybrid actor's “agenda” and attain its “goals.”Footnote 13 Specifying hybrid operations in these terms projects a scenario which, while relegating kinetic warfare to the far end of the spectrum, still results in a cognitive environment haunted by the threat of military force.Footnote 14 Moreover, Cederberg and colleagues’ apposite description of hybrid influencing applies equally well to the case of Chinese “reunification” operations, which “may appear to have ceased … while that particular situation may in reality serve the greater goals of the threat actor, or serve as time used to prepare the ground for future operations.”Footnote 15 In spite of criticism of the conceptual utility of hybrid influencing, which is based on the assumption that overt threats to use military force tend to provoke a self-defeating reaction that undercuts the impact of covert influence operations,Footnote 16 Beijing's painstaking perseverance in upholding its military threat while contemporaneously pursuing influence operations supports the hypothesis that hybrid influencing possesses at least an explanatory power for sub-optimal hybrid strategies in a context where the strategic calculus is heavily shaped by domestic drivers and, above all, concerns of regime survival and legitimacy.

From this standpoint, we research a set of interrelated issues virtually novel to the literature on China's activity in the hybrid domain and Beijing's Taiwan policy. How does Taiwan's international status shape the articulation of Chinese lawfare? What legal tools are deployed by Beijing to execute its strategy of hybrid influencing? Moreover, to what extent does legal warfare shape the contours of the cross-domain, cumulative logic of Chinese hybrid influencing? In answering these questions, through analysis of primary documents and semi-structured elite interviews, we offer a new case study in the literature on Chinese legal warfare, which has mostly focused on the South and East China Seas, and in the literature on hybrid threats to liberal democracies. It remains, however, beyond the scope of our research to provide either an evaluation of the relative success of PRC hybrid influencing or an account of Taiwan's response to it, even though we acknowledge that such an endeavour has significant implications for shifting the cross-Strait balance of power and as such could be an important focus of future academic and policy research.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section lays the legal foundation for empirical analysis of Chinese hybrid influencing targeting Taiwan by delineating Taiwan's uncertain status as a matter of international law. The article continues by examining the origins of Chinese lawfare as a component of the PLA's “three warfares” and its role within the broader strategy of hybrid influencing, positing three main principles as a heuristic for illuminating Beijing's lawfare strategy vis-à-vis Taiwan. Finally, we provide an empirical account of China's hybrid influencing operations across the DIMEFIL domain which fleshes out the centrality of lawfare. We then conclude with reflections on the significance of the implications of a new approach to the study of Chinese hybrid strategy focusing on lawfare for future research.

Taiwan's International Status

Taiwan's inherent vulnerability to Beijing's hybrid influencing, and in particular to operations in the legal domain, stems from its ambiguous status in international law, itself an anachronistic legacy of China's civil war (1945–1949), in the wake of which the absence of a peace treaty between the Nationalists and Communists left the question of sovereignty over the island essentially unresolved. On the one hand, prima facie Taiwan today possesses the four elements of statehood enumerated by the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (1933).Footnote 17 On the other hand, when Japan surrendered to Chiang Kai-shek 蔣介石 as the commander-in-chief of the Republic of China (ROC), it agreed to abide by the Potsdam Proclamation that provided for Formosa and the Pescadores to be returned to the ROC. In the Treaty of San Francisco (1951), concluded with the Allied Powers, Japan renounced “all right, title and claim to Formosa and the Pescadores”; however, in whose favour was not expressly stated, thus leaving the status of Taiwan undetermined. Over the ensuing decades, a critical mass of states switched diplomatic recognition to the PRC, especially after 1971 when the PRC was seated at the UN and the ROC thence expelled.

As a matter of international law, the question of statehood cannot be adequately resolved by analysis of UN membership or diplomatic recognition alone; for the constitutive theory of statehood, which held sway in the 19th century (according to which a state exists exclusively by virtue of the recognition of other states), has been displaced in modern jurisprudence by the declarative theory that holds that an entity becomes a state solely by operation of law, independent of any formality of recognition.Footnote 18 Neither theory is dispositive in Taiwan's case; suffice it to say, at best, recognition by other states is merely evidence of statehood but not a requirement. Thus, legal arguments can be made either way given that the ROC is increasingly isolated diplomatically, albeit still recognized by a fluctuating group of mostly small states numbering 13 in 2022. In addition, Taiwan continues to participate in 22 international organizations under myriad legal personalities and conducts relations with over 140 states.Footnote 19

Leaving aside the vexed issue of in which China the sovereignty of Taiwan is vested, if the principle of self-determination applies – given that Taiwan has never been administered by the PRC and the experience of 70 years of de facto independent territorial government arguably could tend to the creation of a separate Taiwanese people – then under international law it is unlikely that the island could be transferred to the PRC without the consent of the 23.8 million Taiwanese people. Taiwan's international legal status is perhaps best summarized by the renowned jurist James R. Crawford: “The conclusion must be that Taiwan is not a State because it still has not unequivocally asserted its separation from China and is not recognised as a State distinct from China.”Footnote 20 However, the corollary of that statement, of course, is that if Taiwan was to declare independence, with a degree of diplomatic recognition it could immediately become a state, at least purely as a matter of international law. Therefore, unless and until the Taiwan question is conclusively resolved, just as nature abhors a vacuum, it is the legal uncertainty surrounding the status of Taiwan which creates an opportunity for strategic competition. Presently, we shall explore the evolving significance of lawfare in Chinese military theory.

China's Three Warfares and Lawfare Targeting Taiwan

Lawfare has been described as “the use of law as a means of accomplishing what might otherwise require the application of traditional military force.”Footnote 21 Rooted in the novel security challenges of post-Cold War US unipolarity, the concept has a parallel filiation between the US and Chinese strategic studies literatures. It was introduced in US military, policy and academic environments between the late 1990s and the early 2000s through USAF (ret.) Major General Charles J. Dunlap Jr.'s seminal work.Footnote 22 Even though Dunlap has consistently stressed its ideologically neutral nature,Footnote 23 his coining of the term “lawfare” reified US concerns about the manipulation of domestic and international laws by enemy actors in the asymmetric conflicts of the post-Cold War era. Its salience was further boosted by the War on Terror and conflicts in the Greater Middle East. For these reasons, Anglophone scholarship has been shaped by two intellectual preoccupations. First, a profound concern for the “legality” of the concept, namely how lawfare is employed in relation to the rule of law, and whether it is possible or even meaningful to distinguish between “legal” and “illegal” lawfare.Footnote 24 Second, and closely related to the former, a focus on the deployment of lawfare in battlefield scenarios.Footnote 25

By contrast, Chinese conceptualizations of lawfare can be traced back earlier to 1999, when PLAF Colonels Wang Xiangsui 王湘穗 and Qiao Liang 乔良 published their monograph, Chaoxian zhan 超限战 (Unrestricted Warfare). In a survey of various types of “non-kinetic wars,” Wang and Qiao defined “international legal warfare” as a particular type of conflict tasked with “seizing the earliest opportunity to establish rules/standards” (bawo xian ji chuangli guize 把握先机创立规则).Footnote 26 Echoing concerns about the evolution of conflict present in Dunlap's work, Wang and Qiao's concept of “boundary-transcending warfare” was also a product of the post-Cold War US unipolar moment, but one emerging from the distinct perspective of actors having to bear the brunt of a hegemon capable of projecting absolute superiority in a kinetic conflict. Following the publication of Unrestricted Warfare, Chinese conceptualizations of legal warfare emerged within the broader PLA theory of the “three warfares,” which was formally incorporated into the PLA Political Work Regulations on 5 December 2003 by the Central Military Commission and the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and officially promulgated in 2005.Footnote 27 Interviews with intelligence analysts and senior members of the National Security Council (NSC), both serving and retired under a variety of administrations, indicate that although there is currently no evidence in the public domain to suggest that the “three warfares” theory is a formal PLA doctrine, it is treated as such by the ROC foreign policy executive. Interviewees pointed out that only rarely does classified military doctrine emerge in the public domain.Footnote 28 Moreover, the importance of the “three warfares” is underscored by the fact that apart from being referred to 16 times in the landmark, first-ever National Security Strategy in 2006, every biennial defence report released subsequently has referenced it.Footnote 29

The theory of the “three warfares” centres on an indigenous fusion of “psychological warfare” (xinlizhan 心理战), “public opinion warfare” (yülunzhan 舆论战) and “legal warfare” (falü zhan 法律战).Footnote 30 Psychological warfare is designed to sap the “morale” of an enemy's armed forces and the political elite, manipulating actors into internalizing perceptions of subalternity, threat and impotence. Public opinion warfare, however, aims at shaping the “will” of the target country's public opinion,Footnote 31 or more specifically in the cross-Strait context, moulding Taiwanese public perceptions of China through narratives which emphasize the benefits of integration and discredit the status quo and independence-leaning positions in order to mollify resistance and foster a climate conducive to eventual “reunification.” In contradistinction, the role of lawfare is that of “controlling the enemy through the law, or using the law to constrain the enemy” (yifa zhidi 以法制敌).Footnote 32

Sinophone sources have defined a lawfare toolkit consisting of “legal deterrence, legal attack, legal counterattack, legal binding, and legal protection.”Footnote 33 Western scholars characterize Chinese lawfare as the “use of all aspects of the law, including national law, international law, and the laws of war, in order to secure ‘legal principle superiority’ and delegitimize an adversary,”Footnote 34 with some US analysts emphasizing the use of “legal layering,” “rotating arguments” and the passage of domestic legislation to provide “a ‘veneer of legality’ as China attempts to change the status quo.”Footnote 35 Theoretical distinctions between the three, and in particular between psychological and public opinion warfares, however, should not be overemphasized, as the “three warfares” are better conceptualized synergistically as components of a comprehensive system of thought on non-kinetic warfare that focuses on the control of the cognitive sphere and the emotions of the adversary. Critically, the expanded conception of war underpinning the “three warfares” leads to an articulation across different levels of conduct: tactical, operational and strategic. Strategic use of the “three warfares” in particular aims to “protect (or expand) national interests” and is thus “carried out in peacetime as well as wartime.”Footnote 36 This framing, in turn, provides Chinese lawfare with a specific “strategic horizon,” whereas Western scholars are mainly concerned with lawfare in the tactical battlefield environment.

A number of academic commentaries on Chinese hybrid warfare published in the second half of the 2010s framed Beijing's operations targeted at Taiwan in terms of the “three warfares.”Footnote 37 Lingering issues regarding the level of conduct and identity of PRC bureaucratic actors involved in lawfare confirm that it plays a role in explaining Beijing's hybrid strategy, as the frame of analysis is scaled up from hybrid warfare and deployed by China with laser-like focus to target Taiwan. Setting aside a certain proliferation of labels within the literature, the crucial feature of the “three warfares” is the considerable degree of ambiguity in the identity of the key bureaucratic actors involved, as lawfare at this level of conduct relies on legal initiatives planned and promulgated by actors other than the PLA. This is particularly relevant in the case of policymaking regarding Taiwan, given the PLA's relations to other Party organs such as the Taiwan Work Leading Small Group, the Ministry of State Security and the United Front Work Department.Footnote 38 The “three warfares” captures a key dynamic of Beijing's hybrid strategy towards Taiwan – namely, the use of legal tools to first establish the perimeter for Chinese operations in what can be holistically defined as the “cognitive domain” (renzhiyu 认知域) and then bolster their impact.Footnote 39 Yet its PLA intellectual provenance, as well as the scope and outreach of Beijing's DIMEFIL operations, which involve a wider range of Chinese bureaucratic actors, demonstrate that lawfare's role transcends the “three warfares” and requires a broader conceptual frame such as hybrid influencing to be properly understood.

Based on these premises and constructing a simplified explanatory framework to guide analysis, we argue that China's lawfare against Taiwan can be reduced to three non-mutually exclusive foundational principles. The first principle is to recast the relationship between Beijing and Taipei as being an internal dispute between a central and local government, a framing that is explicitly mentioned in the “Suggestions on the correct terminology for Taiwan-related propaganda” issued by the PRC Taiwan Affairs Office in 2012.Footnote 40 This is the most axiomatic of the three principles from which the other two readily derive. In legal terms, the benefits that would flow from China's successful application of the first principle include preserving the PRC's veto power at the UN Security Council, which could be used to prevent Security Council authorization of military action against Beijing or the implementation of Chapter VII sanctions in the event of a cross-Strait conflict. Under Article 27(3) of the United Nations Charter, parties engaged in a dispute that endangers international peace and security shall abstain from voting. However, following the precedent of the UK during the 1982 Falklands War with Argentina, if the PRC were to successfully argue the matter was a domestic affair, it could avoid abstaining in order to exercise its veto power as a permanent member of the Security Council, thereby undermining the legal basis for partners and allies to aid Taiwan on grounds of self-defence under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, even in the event of unprovoked and unequivocal aggression.Footnote 41 More significantly, under the non-intervention principle of international law, if a conflict with Taiwan was considered to be an internal matter of the PRC or a civil war, then any military aid or deployment of foreign forces (a likely decisive factor in a cross-Strait contingency) must be pursuant to the request of a legal government, otherwise the intervention is wrongful. The remedies available under international law for wrongful intervention are quite extensive, and if an intervention were to exceed the threshold of an “armed attack,” then the PRC could invoke the right to self-defence, which in turn makes available an even broader array of lethal options. Manifestly, PRC Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin's 汪文斌 assertion in June 2022 that the Taiwan Strait is not an international waterway has implications that transcend the realm of ideological and political rhetoric.Footnote 42

Second, PRC lawfare towards Taiwan aims to eliminate diplomatic recognition of the ROC and exclude it from participating in international organizations, or else, as an extension of the first principle, to limit ROC participation on terms that effectively designate it as a province of the PRC. In fact, in their analysis of Taiwan's status under international law, PRC scholars still heavily rely on the constitutive theory of statehood, despite its antiquated status from the point of view of modern jurisprudence and state practice.Footnote 43

Third, the final objective of PRC lawfare is to contain and erode the ability of Taiwan to exercise any right of self-determination. Notably, the considerable degree of overlap and interaction between these three principles in the implementation of Chinese lawfare towards Taiwan is fully consistent with the use of “legal layering” and “rotating arguments,” which US scholars have already observed in the case of Chinese lawfare in the South China Sea.Footnote 44

The centrality of lawfare to the toolkit of sub-kinetic hybrid influencing arises from what Orde Kittrie refers to as “compliance-leverage disparity.”Footnote 45 In other words, beyond merely providing a potential source of legitimacy, the fact that unlike liberal democracies, which are enmeshed and bound by the constraints – not to say straight-jacket – of the rule of law, Beijing has an asymmetric advantage in its ability to selectively apply or discard rules and laws in the service of its strategic objectives according to the exigencies of the moment.Footnote 46 Although it is almost impossible to disaggregate and individually quantify all the moving parts when assessing hybrid influencing, one of the manifest advantages of lawfare in comparison with other components is its low outlay in terms of the expenditure of resources. This is especially so in a specific cross-Strait context, where the potential cost of the application of military force at the present juncture arguably remains prohibitive, given the difficulties that would need to be overcome for the PLA to mount a successful amphibious invasion of the island. Moreover, as shall be unpacked in the case study analysis below, during phases of cross-Strait relations where there are fewer direct contacts between the two sides and therefore the surface area for exerting other types of influence along the DIMEFIL spectrum is commensurately diminished, the reliance on lawfare as a tool to exert a magnetic force at a distance across the Strait becomes more pronounced.

The Dynamic of Hybrid Influencing

Having established the context and principles of Chinese lawfare targeting Taiwan, using a methodology of explaining-outcome process tracing, we proceed to provide an empirical account of China's hybrid influencing operations to demonstrate its salience in the articulation of Beijing's strategy for staying the island's drift towards de facto independence and advancing its objective of “reunification.” We argue that the genesis of Chinese lawfare was intrinsically a dynamic response to check President Chen Shui-bian's brief flirtation with referenda as a possible path for Taiwanese independence in the early 2000s. The Standing Committee of the Politburo responded to Chen's challenge with the establishment of a Leading Small Group for Drafting a Special Law on Taiwan in 2003, which was tasked with the drafting of the Anti-Secession Law that was eventually promulgated on 14 March 2005.Footnote 47 Markedly, while not implying causation, there is an unmistakable temporal correlation between the formalization of Chinese lawfare within the “three warfares” proper and the legislative path leading to the promulgation of the Anti-Secession Law.Footnote 48 Specifically, Article 8 of the Anti-Secession Law is drafted very broadly and purports to authorize the use of military force in two sets of circumstances pertaining to (1) Taiwanese independence, which is characterized as “secession” from the mainland, or (2) the exhaustion of peaceful means of “reunification.”Footnote 49 In part itself a reaction to a distorted reading of Section 3(a) of the Taiwan Relations Act (1979), which requires the United States to supply Taiwan with weapons to maintain an independent self-defence capability and is perceived by Beijing to be an act of “lawfare” against the PRC,Footnote 50 the Anti-Secession Law can be construed, at one level, as the use of domestic legislation to create a justification for the use of force against Taiwan. Irrespective of the fact that the stipulations of domestic legislation per se are irrelevant to the question of whether the use of force under international law is legal or otherwise, qua instrument of lawfare, the Anti-Secession Law sends a clear signal that the PRC would respond to a de jure declaration of independence with military force. As such, it is more significant in terms of its modulating impact on international and domestic politics rather than any strict legal effect.

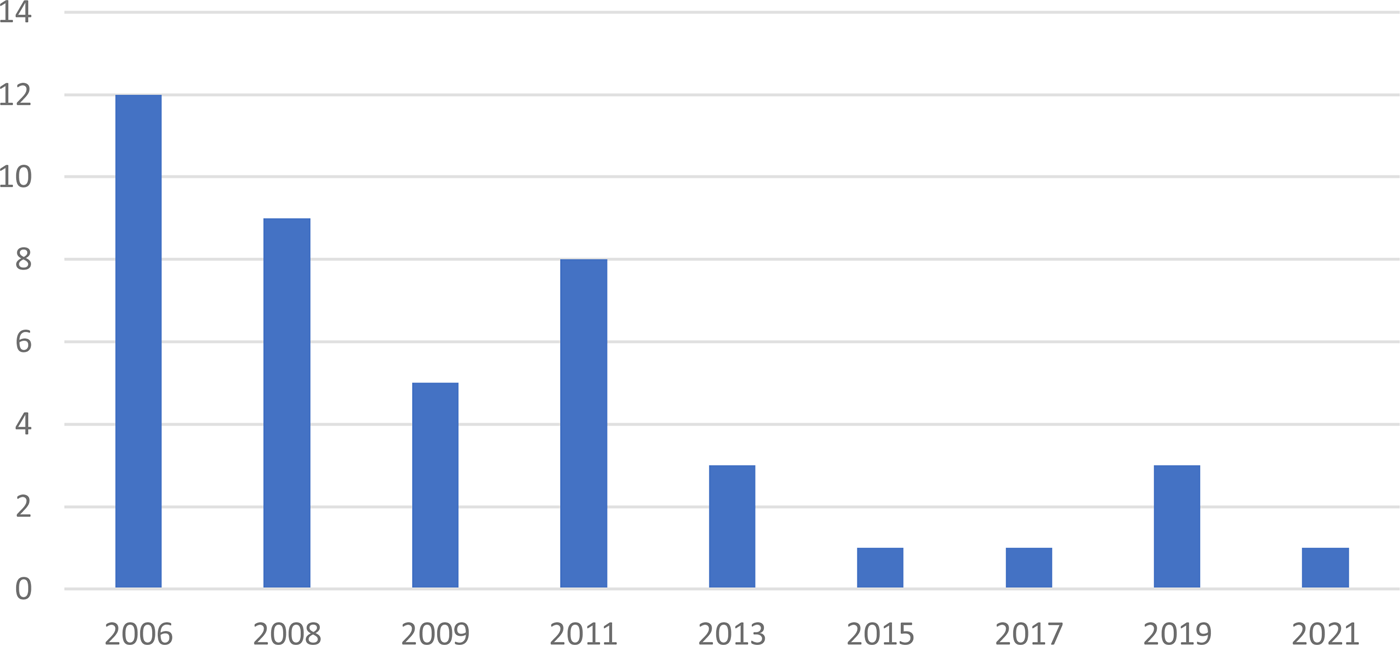

After the Chen administration's abortive experimentation with referenda on cross-Strait issues in 2004, which stalled after failing to garner the support of 50 per cent of registered voters following an engineered pan-Blue boycott, the momentum of the independence movement was dissipated; indeed, during Chen's second term, the only referendum on UN membership also failed because of insufficient turnout. While not the sole determinant in the maelstrom of international politics during the mid-2000s,Footnote 51 the Anti-Secession Law, by laying down the PRC's redlines on Taiwan independence, directly shaped the course of cross-Strait relations as well as the long-term electoral viability of pro-independence political actors in Taiwan. The Chen administration, in the first ever National Security Report issued in 2006, defined the Anti-Secession Law as the “foundation” of an “all-round legal struggle” (quanfangwei de falü zhengduo 全方位的法理爭奪) aimed at “eliminating” the “factual existence” of the ROC.Footnote 52 Elite interviews conducted in Taipei confirm the importance of the “three warfares” in relation to Taiwanese threat perceptions; in addition, the strategy is referenced in every biennial defence report published by the ROC Ministry of National Defense (MND) until 2021, with varying frequency according to shifting threat perceptions, as depicted diagrammatically in Figure 1.Footnote 53

Figure 1: Frequency of Citations of the “Three Warfares” in MND Biennial Defence Report

In this way, a smouldering brushfire that could have ignited during the second term of the Chen presidency was dampened down by the passing of the Anti-Secession Law and eventually extinguished when the Kuomintang (KMT) candidate, Ma Ying-jeou, won a decisive victory in the 2008 general elections. With the overt elements of the hybrid strategy – including most forms of lawfare – now dialled down, this new phase of cross-Strait relations during the two terms of the Ma administration saw Beijing shift gears and switch to more nuanced, ostensibly less coercive, covert levers. The major emphasis was placed on socioeconomic integration and climaxed with the signing of the Economic Comprehensive Framework Agreement (ECFA) in 2010. This, in turn, underlines the organic nature of hybrid influencing, whose tempo can be dialled up and down according to the temperature of cross-Strait politics.

Cross-Strait rapprochement, however, eventually lost its direction following a popular backlash during the 2014 Sunflower Movement which culminated in a student occupation of the Legislative Yuan, thwarting the ratification of the 2013 Cross-Strait Trade Service Agreement, notwithstanding a pan-Blue majority. Thus, in the shadow of the Anti-Secession Law, which ushered in a new phase of Beijing's hybrid influencing – one in which economic statecraft took the driving seat as the centrepiece of a flexible strategy carefully conceived and meticulously implemented to progressively narrow the political choices available to the Taiwanese electorate and political actors – following further setbacks, the approach needed to be recalibrated. Demonstrating resilience and resourcefulness, Beijing again altered the tempo of its hybrid influencing, amplifying the use of covert means in its elusive quest for “reunification.”

This perceptible shift, however, represented only one facet of China's cross-domain hybrid strategy. Following its establishment during the Ma administration in 2010, PLA Base 311 in Fujian was reportedly tasked with the production and dissemination of media content targeting the Taiwanese public; it became, as such, the ground zero of political warfare against the island.Footnote 54 In 2015, command of that base was transferred to the PLA Strategic Support Force. This followed far-reaching military reforms in 2015 and signalled a new focus on operations aimed at controlling Taiwan's cognitive domain.Footnote 55 Put differently, psychological and public opinion warfare were waged around a perimeter defined by lawfare (the Anti-Secession Law) and economic statecraft. The latter, in particular through cross-Strait economic integration, led the way to the emergence of an information infrastructure favourable to Beijing,Footnote 56 which ramped up the dissemination of false information and advertisements within Taiwan's media ecology.Footnote 57 In short, the Ma era encapsulates a distinct dynamic of hybrid influencing: organized beyond a short-term time horizon, implemented across multiple domains, characterized by a distinct tempo and masquerading as an apparent hiatus, all of which served the greater goals of Beijing as it prepared the ground for future operations.

The shift towards economic statecraft and information operations as weapons of choice during the Ma administration did not mean, however, an abandonment of lawfare, as demonstrated by the PRC's use of the “1992 Consensus” to reframe relations between Beijing and Taipei as those between a central and local government.Footnote 58 The term was actually coined in 2000 by the KMT politician Su Chi 蘇起 to retroactively describe the outcome of a meeting between representatives of the PRC and ROC in colonial Hong Kong. Allegedly – for no written records of this meeting exist – both sides agreed to recognize the existence of “one China,” although they respectively disagreed on the meaning of “China.”Footnote 59 While such an “agreement to disagree” is essentially an artful diplomatic fudge with no legal significance, the subsequent actions of the PRC insinuate that the 1992 Consensus is akin to a binding bilateral treaty. In this vein, Taiwanese analysts from the Fu Hsing Kang College of Political Warfare at the National Defense University characterize as “lawfare” an attempt by the pro-unification People First Party to introduce legislation that would have enshrined the 1992 Consensus in law following a meeting between former KMT politician James Soong Chu-yu 宋楚瑜 and President Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 in Beijing in 2005.Footnote 60 The sedulous refusal of President Tsai Ing-wen on assuming office in 2016 to recognize the 1992 Consensus is pointedly the official reason for denying Taiwan the same level of access to international organizations that it had during the Ma era, exemplifying how Beijing simultaneously leverages the first two prongs of its lawfare strategy to exclude Taiwan and heighten its international isolation.

Using the 1992 Consensus to reframe PRC–ROC relations is closely linked to another strand of PRC lawfare, namely the long-term campaign to whittle away diplomatic recognition of the ROC. Having suspended the poaching of the ROC's diplomatic allies during the Ma administration, this détente ended when Tsai Ing-wen came to power in 2016, with five states swiftly switching diplomatic recognition from the ROC to the PRC. Recognition of the “one-China” policy and de-recognition of Taiwan, in turn, are sine qua non for establishing diplomatic relations with the PRC, reinforcing what is a typical “three warfares” dynamic: by reducing the international space available for Taiwan and accentuating a cognitive domain marked by perceptions of isolation and impotency, Beijing is painstakingly seeking to soften and hollow out the residual resistance of the Taiwanese people to its ultimate “reunification” objective.

The PRC's “Several measures to promote cross-Strait economic and cultural exchange and cooperation,” a set of initiatives that came into force on 28 February 2018 and which are designed to beguile Taiwanese businesses and “compatriots” (tongbao 同胞), further flesh out the interplay inherent to hybrid influencing between legal measures, economic statecraft and persuasion operations. Described by Chinese media as the “31 measures” (31 cuoshi 措施), the unilateral package offers Taiwanese businesses the same treatment as their mainland counterparts in connection with a range of initiatives including the “Made in China 2025” strategic plan, the reform of China's state-owned enterprises and Belt and Road-related projects. The measures also enable Taiwanese residents in mainland China to access a variety of national schemes, funds and examinations for professional qualifications previously available only to PRC nationals.Footnote 61 Following reduced people-to-people contact during the Tsai administrations, Taiwanese businessmen (taishang 台商) were one of the few remaining conduits for socioeconomic influence, attesting to the protean adaptability of hybrid influencing. The lawfare dimension arises in that the “31 measures” package is likely to be unlawful under WTO rules: Beijing and Taipei are both WTO members, and under the Most Favoured Nation principle, any special treatment the PRC accords to “Chinese Taipei” must also be made available to all other WTO members. Since the strategic objective of violating WTO rules is to co-opt Taiwanese commercial elites and alter societal perceptions such that the island's people regard themselves better off as citizens of the PRC, the “31 measures” may be regarded as what some scholars describe as “illegal” lawfare. Two events further highlight the inextricable linkages between legal warfare, economic statecraft and public opinion warfare to hybrid influencing. First, a considerable uptick in the dissemination of disinformation on local social media in the run up to the November 2018 municipal “nine-in-one elections.”Footnote 62 Second, an intensification of “united front work” targeted at the ganglia of Taiwanese society, from the local media ecosystem to academia and even religious organizations.Footnote 63 This has been confirmed by investigative reports published by the Financial Times and Reuters in 2019, which have revealed Beijing's financing and even direct control of Taiwanese media sponsoring the “31 measures.”Footnote 64

To complete a final piece of the “reunification” puzzle – although the subject of Taipei's agency in forging an effective counter-hybrid strategy might fruitfully be the subject of a separate paper – the recent efforts of the Tsai administration to comprehensively close loopholes and systematically shore up its legislative defences furnish further indirect evidence of the inchoate hybrid threat perceived by ROC elites as englobing Taiwan. In 2019, there was a systematic overhaul of the “five legislative pillars of national security” (guo'an wufa 国安五法), namely the National Security Act, the Classified National Security Information Protection Act, the Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area, Chapter II of the Criminal Code of the ROC pertaining to treason offences, and the National Intelligence Service Law.Footnote 65 A full treatment of the amendments is beyond the scope of this article, but by way of summary, the amendments sought to plug gaps in existing legislation. For example, owing to the fact that under the ROC constitution the PRC is not explicitly defined as a separate country, certain offences might not be deemed applicable to the mainland. Furthermore, the amendments enhance penalties for existing offences; criminalize mischiefs such as establishing an organization in Taiwan for the official use of foreign countries or the mainland; regulate investments in Taiwanese companies (jiawaizi zhenluzi 假外资真陆资); widen offences concerning the collection of classified information to include confidential government information and online information stored in Taiwanese servers; expand legal surveillance powers to cover the internet; adjust systems of declassification to ensure that intelligence-gathering methods and sources remain secret forever; adjust and even abolish the statute of limitations in relation to offences committed by retired military personnel and former government employees; and establish new mechanisms for the coordination of intelligence sharing between agencies. As a cornerstone of these reforms, the Anti-Infiltration Law (fan shentou fa 反渗透法, AIL hereafter) was promulgated on 15 January 2020.Footnote 66 The AIL is an attempt to codify the law by defining “sources of infiltration” (shentou laiyuan 渗透来源) to include organizations and institutions, political parties and political organizations of external hostile forces (i.e. the PRC) or their agents and organizations established by the above, and then amend Taiwan's existing legislation to impose harsher penalties where infiltration occurs. These moves are distilled in Table 1 for convenient reference.

Table 1: Taiwanese Legislation to Combat Infiltration

Conclusions

In this article, we have identified hybrid influencing as the overall paradigm governing Chinese operations to check Taiwan's drift towards independence and subtly steer it instead towards the PRC's goal of national “reunification.” Scanning the strategic horizon and flitting between multiple domains with alacrity, Beijing's hybrid influencing strategy emphasizes cross-domain operational interplay, cumulative impact and flexibility in the use of different levers of power according to shifts in the China policy of different administrations in Taipei. Above all, hybrid influencing provides an explanation for the sui generis coexistence of latent military threats together with influence operations that, both covertly and overtly, aim at shaping the spectrum of choices available to Taiwanese policymakers and their electorates. Central to this effort, alongside Taiwan's inherent vulnerability owing to the enduring ambivalence of the island's international legal status as a legacy of China's civil war and Cold War geopolitics, the open nature of Taiwan's democratic political system, and the widening power asymmetry across the Strait, is a weaponized conception of law as “lawfare,” which was originally formalized as a component of the PLA's “three warfares” in the mid-2000s.

Whereas Anglophone scholarship has tended to focus on the use of lawfare in kinetic environments and, more recently, as a tactic in grey zone scenarios, our research has demonstrated that lawfare, within the context of hybrid influencing, has been flexibly deployed as part of a disciplined system of military thought along a continuum from non-kinetic to kinetic warfare to achieve tactical, operational and strategic objectives in peacetime as well as potentially during an armed conflict. Moreover, scaling up to the strategic horizon not only yields input from a broader range of bureaucratic actors in China's foreign policy executive beyond the PLA, in a manner not dissimilar to the impact of the confounding logic of the “military–civil fusion” strategy (junmin ronghe 军民融合), it also creates a degree of cognitive dissonance, the implications of which Western strategists and policymakers essentially mirror-imaging their own conceptions of lawfare have struggled to fully grasp and address. In contrast, unsurprisingly given Taiwan's location on the frontlines of an intensifying geo-strategic competition with China in the Indo-Pacific, and with arguably the most at stake, the strategic ramifications of the “three warfares” were not lost on Taipei.

Given these premises, our study has posited three principles of PRC lawfare towards Taiwan as a succinct explanatory framework to guide analysis: reframing the relationship between Beijing and Taipei as an internal dispute between a central government and local government, eliminating diplomatic recognition of the ROC and excluding Taiwan from participation in international governmental organizations except on terms that cast Taiwan as a province of the PRC, and containing Taipei's exercise of any right to self-determination. The application of these three principles, whose deceptive simplicity should not detract from the power of their legal logic, in conjunction with operations of both coercive and attractive nature proper to hybrid influencing involving in particular the diplomatic, information, military and economic domains, has been examined in the context of the Anti-Secession Law, the 1992 Consensus, the “31 measures” and the ROC's Anti-Infiltration Law.

More research by Sinologists, political scientists and the analytical community might be able to elucidate the operationalization of lawfare and the “three warfares” (if not fully resolve the unfathomable matrix composing China's strategy of hybrid influencing more broadly), thereby opening the black-box of PRC Taiwan policy and shedding light on interactions between such organs as the Taiwan Affairs Leading Small Group and the PLA's Political Work Department, Joint Staff Department, Strategic Support Force and Base 311. As such, with more information percolating into the public domain in the months and years ahead, the “fourth Taiwan Strait crisis,” which was precipitated by US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi's visit to Taiwan on 2–3 August 2022, might provide an excellent data point for analysing the concerted orchestration of diffuse elements of China's hybrid influencing strategy. As an increasingly assertive China ratchets up its efforts to unify Taiwan optimally without provoking a military conflict with the United States, its partners and allies, the allure of “winning without fighting” will only grow greater.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Chang Chihyun, Chang Wu-ueh, York Chen Wen-jenq, Fu Hualing, Ho Szu-yin, Hsieh Yi Shiun, Alexander C. Huang, Barak Kushner, Li Da-jung, Ying-Yu Lin, Ma Cheng-Kun, Shen Ming-shih, Steve Tsang, Tzeng Yi-Suo, Wang Kaochen, Wang Yuh-woei, Wong Ming-hsien and Andrew Yang Nien Dzu for their invaluable assistance in facilitating fieldwork. The authors would also like to thank three anonymous reviewers, as well as Sheena Chestnut Greitens, Rosemary Foot, Courtney J. Fung, Doyle Hodges, Nicola Leveringhaus, Rana Mitter and Giulio Pugliese for their insightful feedback.

Competing interests

None.

Michael J. WEST is a lecturer in the Faculty of Law at the University of Hong Kong. He earned his PhD in law from the University of Hong Kong and a BA and MA from the University of Oxford. He is admitted as a solicitor in Hong Kong and is fluent in Mandarin and Cantonese.

Aurelio INSISA is an adjunct assistant professor in the department of history at the University of Hong Kong. He holds a BA and MA in Asian Studies from Sapienza University of Rome and a PhD in Chinese history from the University of Hong Kong. He is the co-author of Sino-Japanese Power Politics: Might, Money and Minds (Palgrave, 2017) and has published articles in International Affairs, Asian Perspective and The Pacific Review, among others.