Cornelia de Lange syndrome is associated with abnormalities on chromosomes 5, 10 and X. Reference Krantz, McCallum, DeScipio, Kaur, Gillis, Yaeger, Jukofsky, Wasserman, Bottani, Morris, Nowaczyk, Toriello, Bamshad, Carey, Rappaport, Kawauchi, Lander, Calof, Li, Devoto and Jackson1–Reference Deardorff, Kaur, Yaeger, Rampuria, Korolev, Pie, Gil-Rodríguez, Arnedo, Loeys, Kline, Wilson, Lillquist, Siu, Ramos, Musio, Jackson, Dorsett and Krantz4 The physical phenotype includes small stature, limb abnormalities, facial dysmorphology and gastrointestinal and kidney disorders. Reference Kline, Krantz, Sommer, Kleiwer, Jackson, Fitzpatrick, Levin and Selicorni5 Degree of intellectual disability ranges from mild to profound, Reference Berney, Ireland and Burn6,Reference Kline, Stanley, Belevich, Brodsky, Barr and Jackson7 expressive communication is relatively poor Reference Hawley, Jackson and Kurnit8 and self-injurious behaviour is prominent. Reference Arron, Oliver, Hall, Sloneem, Forman and McClintock9,Reference Moss, Oliver, Hall, Arron, Sloneem and Petty10 There is evidence for phenotypic differences between genotypes and a distinction is drawn between ‘classic’ and ‘mild’ presentations. Reference Basile, Villa, Selicorni and Molteni11

‘Autistic-like’ behaviours are reported Reference Beck12 and estimates of autistic-spectrum disorder vary from 53% Reference Berney, Ireland and Burn6 to 89%. Reference Bhuiyan, Klien, Hammond, Mannens, Van Haeringen, Van Berckelaer-Onnes and Hennekam13 However, as few studies have employed matched comparison groups the interpretation of these figures is problematic. Reports of autistic-like behaviour in Cornelia de Lange syndrome note repetitive and ritualistic behaviours. Hyman et al Reference Hyman, Oliver and Hall14 reported high levels of compulsive-like behaviours with 87.5% showing at least one form. This high prevalence warrants further investigation by examining whether these behaviours are independent of autistic-like impairments.

In this study we examine communication, compulsive and autistic-like behaviour in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. We predict that these characteristics will be more prominent in people with this syndrome (‘syndrome group’) than in a comparison group. We also investigate the relationship between compulsive and autistic-like behaviour. We employ psychometrically robust methods of assessment and a mixed-aetiology intellectual disability group matched on key characteristics (age, gender, intellectual ability and mobility) for comparison.

Method

Participants

Families were contacted via the Cornelia de Lange Syndrome Foundation support group in the UK. Selection for inclusion was based on age (over 2 years) and location (living near one of five bases). A total of 59 participants with Cornelia de Lange syndrome were identified and all agreed to participate. Since genetic diagnosis was not available at the time of the study, clinical diagnosis was employed. Overall, 51 participants had received a diagnosis of Cornelia de Lange syndrome from a medical professional or professional specialising in the syndrome. The 8 participants with a diagnosis from another source and 5 participants for whom a diagnosis was queried were either confirmed or rejected by a clinical geneticist, eliminating 5 participants. Thus, a sample of 54 individuals with Cornelia de Lange syndrome was formed. All parents or carers gave consent to participate in the study.

To identify a comparison group, two methods were adopted. Teachers and key workers of participants with the syndrome identified up to 2 individuals who were similar to the index participant in terms of age, gender, mobility and ability (n=5). Second, schools and day centres already visited distributed 876 information packs to parents and carers. Altogether, 153 (17.5%) returned consent forms and questionnaires (including the Wessex Scale, Reference Kushlick, Blunden and Cox15 see Measures). Individuals were matched to participants with Cornelia de Lange syndrome in terms of age (+2 years), gender, wheelchair use (‘never’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’) and self-help skills as determined by Wessex scores. A total of 46 comparison participants were identified.

Information on the Wessex self-help scale, mobility, age and gender are presented in Table 1. No specific diagnosis was made in 25 individuals in the comparison group; 21 had syndrome diagnoses including: Down syndrome (n=8); autism (n=3); cerebral palsy (n=2); congenital rubella (n=1); fragile-X syndrome (n=1); Ito syndrome (n=1); Landau–Kleffner syndrome (n=1); Miller–Dieker syndrome (n=1); Prader–Willi syndrome (n=1); Sotos syndrome (n=1); and intellectual disability subsequent to Reye's syndrome (n=1).

Table 1 Mean (s.d.) age, percentage of males, levels of ability and of mobility for both groups

| Variable | Cornelia de Lange syndrome group | Comparison group |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (s.d.) | 13.88 (8.58) | 13.74 (7.99) |

| Range | 3.18-37.91 | 4.25-37.91 |

| Gender, % | ||

| Male | 46 | 50 |

| Wessex Scale (self-help), % | ||

| Not able | 46 | 42 |

| Partly able | 41 | 49 |

| Able | 13 | 9 |

| Wheelchair use, % | ||

| Always | 11 | 11 |

| Occasionally | 33 | 28 |

| Never | 56 | 61 |

Overall, 3.7% of the syndrome group were taking antipsychotic medication, 11.1% were taking anti-epileptic medication and 42.6% other types of non-psychoactive medication. Of the comparison group, 10.9% of participants were on antipsychotic medication, 23.9% were taking anti-epileptic medication and 31.3% other forms of non-psychoactive medication.

Measures

Wessex Scale

The Wessex Scale Reference Kushlick, Blunden and Cox15 is an informant questionnaire designed to assess social and physical abilities in children and adults with intellectual disabilities. It has good interrater reliability at subscale level for both children and adults. Reference Kushlick, Blunden and Cox15,Reference Palmer and Jenkins16

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Interview Edition) Reference Sparrow, Balla and Cicchetti17 measure ability in individuals from birth to 18 years 11 months and in ‘low-functioning’ adults. Three domains of adaptive behaviour were used: Communication, with sub-domains Receptive, Expressive and Written; Daily Living Skills; and Socialisation. Results were obtained as age-equivalent scores. Interrater and test–retest reliability indices, construct, content and criterion validity are robust. Reference Sparrow, Balla and Cicchetti17

Aberrant Behavior Checklist

The Aberrant Behavior Checklist Reference Aman and Singh18 is a measure of problem behaviour incorporating a 58-item checklist with five factors based on observations of behaviour over the previous month, including: irritability, agitation and crying; lethargy and social withdrawal; stereotypic behaviour; inappropriate speech; and hyperactivity and non-adherence. The checklist is completed by caregivers, who rate each behaviour from 0 (not at all a problem) to 4 (problem is severe in degree). Aman & Singh Reference Aman and Singh18 report robust interrater and test–retest reliability.

Compulsive Behavior Checklist

The Compulsive Behavior Checklist Reference Gedye19 is a questionnaire measure comprising 25 items grouped into five categories: Ordering, Completeness, Cleaning, Checking and Grooming. The mean interrater reliability agreement across raters is 84.3%. Reference Bodfish, Crawford, Powell, Parker, Golden and Lewis20

Childhood Autism Rating Scale

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale Reference Schopler, Reichler and Renner21 is an observational rating scale incorporating 15 items developed to identify individuals with autism. Informants rate each behaviour from 1 (no evidence of autistic-type behaviour) to 4 (severe autistic-type behaviour). Aggregate scores of 15–29.5 indicate no autism, 30–36.5 mild to moderate autism and scores of over 37, severe autism. Scores are standardised based on normative data collected from 1500 individuals with autism. Interrater and test–retest reliability, criterion validity and internal consistency are reported to be good. Reference Schopler, Reichler and Renner21

Procedure

Questionnaire and interview measures were completed by the participant's daytime carer. Observers visited each participant and collected videotaped observations of the participant for about 4 h. Following data collection, the videotapes were used to rate relevant items on the Childhood Autism Rating Scale. Ethical review of all aspects of the study was obtained.

Data analysis

For the majority of analyses chi-squared or t-tests were used to compare groups. For analyses for which no prediction was made and multiple comparisons were undertaken (analyses of sub-scales for the Aberrant Behavior Checklist and the Compulsive Behavior Checklist), Bonferroni corrections were applied (P<0.01).

When examining the behavioural phenotype across behaviours to control for covariance, a regression analysis was conducted to predict group membership. The following behavioural variables were force entered into a binary logistic regression equation: total number of compulsions as measured by the Compulsive Behavior Checklist, the total Childhood Autism Rating Scale score, total score on each factor of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist and Expressive Communication sub-domain age-equivalent scores. Post hoc tests (variance inflation factor) were applied to the data to test for multicollinearity.

Results

To ensure that the syndrome group did not differ from the comparison group on matching criteria, statistical comparisons were undertaken. The t-test and chi-squared statistics showed no significant difference between the two groups for age (t(97)=–0.08, P=0.94), gender (χ2(1)=0.14, P=0.71), ability (χ2(1)=0.67, P=0.72) and mobility (χ2(1)=0.33, P=0.85). Analysis of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale data showed no difference between groups for mental-age-equivalent scores (syndrome group: mean=27.43 months (s.d.=20.67); comparison group: mean=27.80 months (s.d.=22.79); t(97)=0.09, P=0.93). The percentage of participants with Cornelia de Lange syndrome with given degrees of intellectual disability were: profound 50.00%, severe 24.07%, moderate 14.81% and mild 11.11%. Equivalent data for the comparison group were 45.65%, 30.43%, 15.22% and 8.70% respectively. These proportions did not differ significantly (χ2(1)=0.62, P=0.89). In combination, these analyses showed that the groups were comparable.

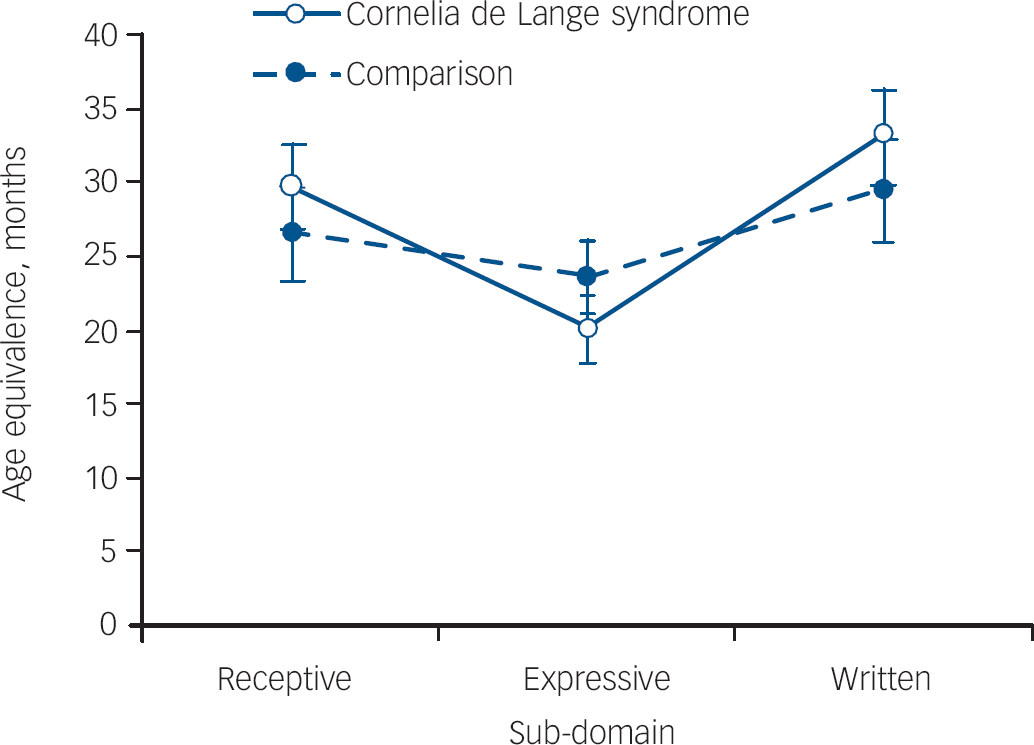

To examine the potential discrepancy between receptive and expressive language abilities, mean age-equivalent scores for the Communication sub-domains of Receptive, Expressive and Written were compared across groups (Fig. 1). A mixed two-way ANOVA revealed an interaction effect (F(2,196)=3.39, P<0.05). Examination of the data in Fig. 1 showed that the syndrome group performed relatively more poorly on the Expressive communication domain compared with other domains than the comparison group.

Fig. 1 Mean-age equivalent scores (in months) (±1 s.e.) for Communication sub-domain of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales for both groups.

Table 2 shows the mean scores for the syndrome and comparison groups on the sub-scales of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist and the Compulsive Behavior Checklist. For the Aberrant Behavior Checklist there were no significant differences between the groups on sub-domains or total score (syndrome group: mean=40.77 (s.d.=34.15); comparison group: mean=32.98 (s.d.=30.87); t(95)=1.71, P=0.24). On the sub-domains of the Compulsive Behavior Checklist, the syndrome group scored significantly higher on the Cleaning and Checking sub-scales (P=0.002 and P=0.006 respectively) with the difference on the Grooming sub-scale approaching significance (P=0.049). The syndrome group showed a significantly higher number of compulsive behaviours than the comparison group (mean=4.12 (s.d.=3.99) and mean=2.67 (s.d.=3.16) respectively; t(95)=2.68, P=0.009). Finally, 86.5% of participants with Cornelia de Lange syndrome and 57.8% of participants in the comparison group displayed one or more forms of compulsive behaviour (χ2(1)=10.17, P<0.01).

Table 2 Mean (s.d.) for the Aberrant Behavior Checklist and the Compulsive Behavior Checklist sub-scale scores for the both groups

| Measure | Cornelia de Lange syndrome group Mean (s.d.) | Comparison group Mean (s.d.) | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aberrant Behavior Checklist | ||||

| Irritability | 10.63 (9.37) | 7.98 (8.76) | 1.17 | 0.24 |

| Lethargy | 9.12 (10.07) | 8.31 (10.16) | 1.42 | 0.16 |

| Stereotypy | 4.23 (5.27) | 3.20 (4.43) | 0.94 | 0.35 |

| Hyperactivity | 13.02 (12.68) | 11.10 (11.64) | 0.78 | 0.44 |

| Inappropriate speech | 1.59 (2.77) | 1.02 (2.32) | 1.10 | 0.28 |

| Compulsive Behaviour Checklist | ||||

| Ordering | 1.15 (1.58) | 0.88 (1.20) | 1.09 | 0.28 |

| Completeness | 0.79 (1.23) | 0.44 (0.14) | 1.61 | 0.11 |

| Cleaning | 0.85 (1.02) | 0.29 (0.66) | 3.24 | 0.002 |

| Checking | 0.81 (0.58) | 0.33 (0.64) | 2.80 | 0.006 |

| Grooming | 0.58 (0.64) | 0.33 (0.56) | 2.00 | 0.049 |

Table 3 displays the percentage of participants in each category of autism. A significantly greater proportion of individuals in the syndrome group (32.1%) scored in the ‘severe autism’ category compared with the comparison group (7.1%).

Table 3 Percentage of participants in each category of autism (as defined by the Childhood Autism Rating Scale) broken down by group

| Group | Non-autistic | Mild to moderate autism | Severe autism | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cornelia de Lange syndrome group | 52.8 | 15.1 | 32.1 | 8.77 | 0.012 |

| Comparison group | 71.4 | 21.4 | 7.1 |

Predicting group membership

A binary logistic regression was conducted to determine the behavioural characteristics that predicted group membership, while controlling for other behaviours. The regression equation was conducted with the following variables: total number of compulsions as measured by the Compulsive Behavior Checklist, the Childhood Autism Rating Scale score, total score on each factor of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist, and Expressive Communication age-equivalent scores from the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale. The regression model correctly classified 64% of cases. Total score on the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (Wald=8.34, d.f.(1), P<0.01, OR=1.15) and total number of compulsions (Wald=4.44, d.f.(1), P<0.05, OR=1.23) significantly predicted group membership when all other variables were controlled for. Post hoc tests revealed that the data did not show multicollinearity.

To examine compulsive behaviours in the syndrome and comparison groups in more detail, a binary logistic regression was also carried out with the five Compulsive Behavior Checklist categories as independent variables. The regression model correctly classified 66% of cases, with the number of cleaning compulsions being the only significant variable predicting group membership (Wald=7.74, d.f.(1), P<0.01, OR=2.36). Post hoc tests revealed that the data did not show multicollinearity.

Discussion

Intellectual disability and impairment of communication

The majority (76%) of participants with Cornelia de Lange syndrome were classified as having severe and profound intellectual disability and this distribution of degree of intellectual disability is similar to that previously reported (Table 4). Reference Berney, Ireland and Burn6,Reference Beck12 This confirms the broad range of intellectual disability in the syndrome and the data in Table 4 suggest that the current sample is representative. Previous literature has indicated that individuals with this syndrome may have deficits in expressive communication relative to their overall adaptive behaviour. Reference Kline, Stanley, Belevich, Brodsky, Barr and Jackson7,Reference Beck12 In this study we identify a deficit of expressive communication in Cornelia de Lange syndrome relative to receptive and written communication that appears to be phenotypic of the syndrome. Future research should employ more sophisticated assessments of language in individuals with the syndrome to investigate this relative deficit as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale is a crude assessment of communication. Additionally, further research should examine the potential role of hearing impairment as contributory to this profile.

Table 4 Percentage of participants with Cornelia de Lange syndrome by category of intellectual disability across studies

| Participants scoring within categories of intellectual disability, % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Measure | n | Profound | Severe | Moderate | Mild | Borderline/normal |

| This study | Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale | 54 | 50 | 24 | 15 | 11 | 0 |

| Beck (1987) Reference Beck12 | Vineland Social Maturity Scale | 36 | 50 | 14 | 17 | 6 | 14 |

| Berney et al (1999) Reference Berney, Ireland and Burn6 | Not reported | 49 | 43 | 20 | 18 | 8 | 10 |

Autistic-spectrum disorder and compulsive behaviour

Previous studies have suggested that individuals with Cornelia de Lange syndrome may have an increased likelihood of showing autistic-type behaviour. Reference Berney, Ireland and Burn6,Reference Moss, Oliver, Berg, Kaur, Jephcott and Cornish23 Our study supports this assertion as individuals with the syndrome were significantly more likely to be categorised as ‘severely autistic’ than individuals in the comparison group. Furthermore, results of a regression analysis to examine the contribution of characteristics to the prediction of group membership indicated that total score on the Childhood Autism Rating Scale was a significant predictor. Thus, variables such as degree of intellectual disability that are known to influence prevalence of autism Reference Nordin and Gillberg24 have been controlled for both in this analysis and in the experimental design. Although this finding is important it requires replication using psychometrically robust measures of autism combined with developmental history and assessments that inform established diagnostic algorithms. Comparisons of phenomenology of autism not associated with syndromes and in high-risk syndromes, such as fragile-X and tuberous sclerosis, are also warranted.

It is notable that no differences were found between the groups on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist at the full-scale or sub-scale level. Previous research has indicated that individuals with Cornelia de Lange syndrome may have an increased likelihood of showing hyperactive and stereotyped behaviour. Reference Berney, Ireland and Burn6 However, our study demonstrates that when employing a matched comparison group no differences are found. The finding of no difference in global behaviour disorder between the two groups also indicates the need for the use of specific measures of behaviour in this type of research given other identified differences.

This study provides further evidence of a high prevalence of compulsive behaviour in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Consistent with the report of Hyman et al, Reference Hyman, Oliver and Hall14 over 85% of participants in the syndrome group showed compulsive behaviour, significantly more than in the comparison group. Analyses also indicated that the syndrome group displayed more compulsions than the comparison group and, critically, the regression analysis demonstrated that the number of compulsions was a reliable predictor of Cornelia de Lange syndrome when autism was controlled for. Although this finding is robust there is need for caution regarding significance. It is not clear that the Compulsive Behavior Checklist is assessing compulsive behaviour as defined by DSM–IV 25 , for example, and some stereotyped behaviours might be included in the assessment. Further research should clarify the phenomenology of the compulsive behaviours and undertake detailed comparisons with other groups.

Future research

Our findings are important for a number of reasons. First, differences between the groups were found for an expressive communication deficit, compulsive behaviours and autism, and these characteristics appear to be phenotypic of Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Second, the results indicate that compulsive behaviours might be more pronounced in this syndrome than would be predicted from the presence of other autistic impairments and this dissociation alludes to the potential for an additional pathway to aspects of the behavioural phenotype. Future research should focus on further delineation of the phenomenology of the phenotypic characteristics noted in this study and their relationship with the genetic subtypes of Cornelia de Lange syndrome that are now being described. Reference Bhuiyan, Klien, Hammond, Mannens, Van Haeringen, Van Berckelaer-Onnes and Hennekam13

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the PPP Foundation. J.S. was supported by a PhD studentship from the Medical Research Council. We are grateful to the Cornelia de Lange Syndrome Foundation (UK and Ireland) for their support, the families and carers of participants and the participants themselves for their diligence and patience. We are grateful to Dr Tonie Kline for her contribution to the diagnostic procedure.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.