“The Great Game” sounds pleasant, playful—maybe the Olympics. But, in fact, the Great Game signifies the bloody, brutal 19th-century struggle pitting the British Empire against Tsarist Russia for access to India, including both economic and political control. As Danish Zahoor describes it:

The theatre of the Great Game was the vast, dusty and untamed Central Asian region lying between the expansive Russian empire in the north and British India in the south. […] The game was characterized by reconnaissance missions undertaken by officers of either side […] seeking glory and advancement in their careers. They would navigate the treacherous towns and bazaars under the disguise of pilgrims, doctors, and merchants, using their knowledge of local tongues like Persian and Pashto to their advantage. Their purpose would be to explore and sometimes map the hitherto unknown terrain, especially strategic mountain passes and rivers of the region, and also to gather intelligence about the political inclinations and motives of the Emirs. Above all, the mutually paranoid rival officials would be most interested in trying to gauge the influence that the other side had been able to achieve amongst the Emirates. (Zahoor Reference Zahoor2021)

The Great Game was played most intensely in Central Asia, Afghanistan, and surrounding territories, more than in India itself. But the moves were strategized by overlords occupying seats of power in London, Calcutta, and St. Petersburg.

The phrase “The Great Game” was first used with regard to Central Asia in 1840 by Captain Arthur Conolly of the 6th Bengal Light Cavalry who served Britain’s East India Company by gathering intelligence in Afghanistan and surrounding regions. On 24 June 1842, Conolly and fellow British officer Charles Stoddart were beheaded for spying in Bukhara, today’s Uzbekistan. Sixty years later, in 1900, Rudyard Kipling made the phrase famous in his novel Kim: “Now I shall go far and far into the North playing the Great Game. […] When everyone is dead the Great Game is finished” ([1900] 1987:203, 200). And sometimes it was very like a game. “‘We shall shoot at each other in the morning,’ one Russian told [Colonel Frederick] Burnaby, handing him a glass of vodka, ‘and drink together when there is a truce’” (Hopkirk Reference Hopkirk1990:368). That Great Game officially ended with the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907. But of course, it didn’t end. The region was a theatre of war for centuries and remains so.

After several governments’ faltering attempts to modernize Afghanistan, a coup brought the Communists to power in 1978. They were immediately attacked by Mujahideen Islamists. To bolster the Communist government, the Soviets got into the act in 1979, unsuccessfully occupying Afghanistan until 1989 when the militant Islamist Taliban took over. The Americans upped the ante in 2001 with the George W. Bush administration’s Operation Enduring Freedom, invading Afghanistan in response to the 9/11 attacks on New York’s Twin Towers and the Pentagon in Washington, DC. Twenty years later, US forces retreated, and the Taliban took over Afghanistan for the second time. After nearly two centuries of conflict, can we imagine all will be peace and quiet from now on?

In 2009, Nicolas Kent, artistic director of Britain’s Tricycle Theatre from 1984 to 2012, commissioned 12 short plays collectively titled The Great Game: Afghanistan (Tricycle Theatre Reference Theatre2010). These ran the gamut from verbatim theatre to fictionalized historical plays, from the first Anglo-Afghan War of 1838–1842 to contemporary narratives. The Great Game: Afghanistan was performed with high success in the UK and later in the US on single days or over the span of a few days.

The Great Game is not over, though its theatre of operations keeps shifting. Today’s playing field is Eastern Europe, focused on Ukraine, the rivals are the NATO powers and their proxy, Ukraine, versus Russia; democracies versus a dictatorship. But that binary is way too simple. The Ukrainians, whose courage we admire and whose cause many of us strongly support, are no angels. Prior to the Russian invasion, the Ukrainian government was called by The Guardian “the most corrupt nation in Europe” (Bullough Reference Bullough2015). Even Ukraine’s great hero, Volodymyr Zelensky, is implicated (Harding Reference Harding, Loginova and Belford2021). Before the brutal Russian invasion, neofascism was on the rise in Ukraine (Golinkin Reference Golinkin2019). Add to this that often the fine-sounding word “democracy” masks global neoliberalism, with its structural inequities and neocolonial exploitations. From another vantage—given the suffering, the displaced civilians, the damage to dwellings, infrastructure, and the environment, the villain of the piece is warfare itself, at least war as humans have waged it from time immemorial.

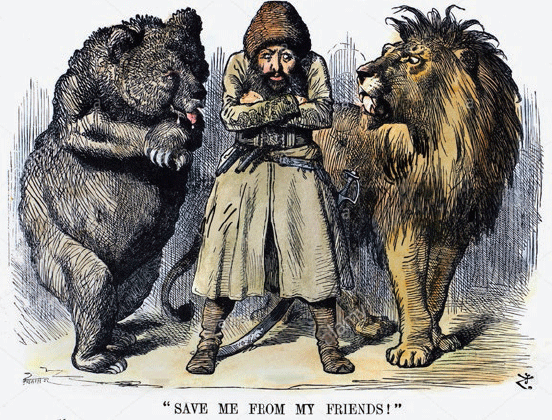

Figure 1. The Great Game: the Afghan Emir Sher Ali Khan with his “friends” Russia and Great Britain. Cartoon by Sir John Tenniel, first published in Punch magazine, 30 November 1878.

We need some performance theory here. What is the difference between “is” performance and “as” performance? Something “is” a performance when historical-social context, convention, usage, and tradition say it is. Theatre, dance, music, rituals, play, sports, the roles of everyday life, and so on are performances because context, convention, usage, and tradition say so. From the vantage of performance theory, every action is a performance. But from the vantage of cultural practice, some actions will be deemed performances and others not; and these will vary from culture to culture, historical period to historical period. On the other hand, anything can be studied “as” performance. That means asking performance questions of whatever is being studied. What happens? What is it called? Where does it happen? How is it performed, staged, and/or displayed? How does it change over time? How is it received by participants, observers, and scholars? In terms of performance theory, there is no limit to what can be studied “as” performance. It is with this in mind that I return to war and the Great Game.

War is a great subject in Eurasian literature, theatre, and performance from the earliest days: The Iliad, The Ramayana, The Mahabharata, Greek, Roman, Elizabethan-Jacobian theatre, Japanese noh and kabuki, Chinese martial arts, down to contemporary popular culture in countless films, documentaries, television shows, and games. The very first word of Vergil’s Aeneid is “arma,” weapons: “Arma virumque cano” (Of arms and the man I sing). Treatises on how to wage war go back at least to Sun Tzu’s Military Method (孫子兵法), 5th century BCE. I assume that peoples everywhere—not just in Eurasia—have made war since time immemorial. At least they have engaged in deadly fights to acquire or keep power, space, mates, and resources.

No one epitomizes the celebratory pride and joy of war better than Shakespeare’s King Henry V:

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

And say “These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.”

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day. […]

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day. (Henry V, 4,3:47–69)

Henry covers all the bases: survival, pride of the war wound, holiday commemorating the battle, great deeds performed, glory, sacrifice, comradeship, social cohesion, elevation of status, manhood.

War also brings dedication to something beyond the self. In the Bhagavad Gita Krishna counsels Arjun:

![]()

(Fight for the sake of duty, treating alike happiness and distress, loss and gain, victory and defeat; see www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org/chapter/2/verse/38)

From Troy to Kurukshetra to Agincourt—and at multitudes of other battlefields—war elevates the warriors. War unifies the in-group (family, tribe, community, nation, alliance of nations) against the out-group (variously designated, but always “not us”). In the social imagination, actual wars are symbiotically joined to their representations in literature, performance, and visual arts. Back and forth, from battlegrounds to playhouses and books, bloodfields to canvases and movie screens, wars waged and wars depicted or imagined give meaning to both individual and collective lives. Yes, often enough, the horrors of war are described and depicted—think Francisco Goya’s The Disasters of War and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s The Vietnam War—but despite all objections, the surpassing narrative is of glory, sacrifice, and accomplishment.

A masculine gender privilege underscores warring in fact and in its representations. Although Amazon women warriors and their pop-culture avatars are there; and although today many armies deploy women on an increasingly equal footing, including going into battle, the narrative remains masculine. Women warriors are “as if” men when they fight. Perhaps this will change over time, but from the past to now, making war is men’s work.

War contributes to society in ways other than generating art and pop culture. Under the pressure of war, new technologies emerge. For example, from WW2: radar, jet engines, computers, microwave ovens, synthetic rubber, antibiotics—and the two-edged invention, nuclear power. War focuses peoples’ attention and enhances social cohesion (often at the expense of perceived internal threats or enemies). As a metaphor, in English at least, the “war on” crime, drugs, poverty—you name it—implies a concerted collective effort, a positive social force.

War, like every other cultural practice, has changed over time, and varies greatly from culture to culture, and one historical period to the next. War comes in many kinds: lightning war, “blitzkrieg,” aka “shock and awe”; raiding, raping, looting; surround, siege, capture, sack; endless war such as in Afghanistan; “total war” targeting civilians and military alike; precision war with drones and pinpoint targeting; “unthinkable” nuclear war, the MAD war of “mutual assured destruction.” The aims of war are variable: defeat the enemy then go home; temporarily occupy the conquered land; dominate and colonize, as with the British Empire; exterminate and settle—think of Jericho and millennia later “Manifest Destiny” decreeing Europeans settling Native American lands “from sea to shining sea.” Many times over, everywhere, and as far back in human history as we can go, wars have been and are being fought.

All of the above can be illuminated by theatre lights. That is because war is often conceived as theatre made for spectating. At one level, this is professional viewing. From line commanders to generals, developing battles are seen and analyzed as performances-in-process. From the noncombatant point of view even more so, war is theatre. As Elizabeth D. Samet writes:

the theatricality inherent in the experience of watching actual battles [was] for centuries a common European practice. Before technological innovations such as rifles, long-range artillery, and airpower dramatically expanded the battlespace, spectators could with a reasonable expectation of safety attend a battle in progress as if it were a kind of theater. History is replete with accounts of spectators—military as well as civilian—observing battles as they unfold. (2013:78–79)

Figure 2. Krishna commands Arjuna. Illustration in Hindi Gita Press Mahabharata.

For example, on 18 June 1815 as Napoleon was losing the bloody Battle of Waterloo numerous noncombatant tourists watched. Napoleon’s adversary, the British Duke of Wellington, complained: “The battle of Waterloo having been fought within reach, every creature who could afford it traveled to view the field” (in Samet Reference Samet2013:79). On its 200th anniversary, Waterloo was reenacted by 5,000 performers before an international audience of 64,000.Footnote 1 On 21 July 1861 the first major engagement of the American Civil War, the Battle of Bull Run, drew a multitude of spectators from nearby Washington, DC. Union Captain John Tidball witnessed a “throng of sightseers” approach his battery:

They came in all manner of ways, some in stylish carriages, others in city hacks, and still others in buggies, on horseback, and even on foot. Apparently, everything in the shape of vehicles in and around Washington had been pressed into service for the occasion. It was Sunday and everybody seemed to have taken a general holiday; that is all the male population, for I saw none of the other sex there, except a few huckster women who had driven out in carts loaded with pies and other edibles [think Brecht’s Mother Courage]. All manner of people were represented in this crowd, from the most grave and noble senators to hotel waiters. (in Burgess Reference Burgess2011)

The US phase of the Vietnam War, 1964–73, was dubbed “the living room war” because video journalists embedded with the troops filmed the war as it was being waged with the footage shown on TV very shortly after the action. Live action reports marked the first Persian Gulf War, 1990–91, and intensified thereafter. The means may be electronic, but the result is much the same as spectating at Waterloo or Bull Run—except that now the warfare is also immediately narrated and analyzed. The Ukraine war is broadcast continuously on US commercial television whose owners profit handsomely from selling advertising. Social media also disseminates war-as-spectacle, and war-as-gruesome-entertainment, a pornography of violence.

Those who theorize war understand it performatively. In his 1832 classic On War, Carl von Clausewitz conceptualized the “theatre of war.”

Theatre of War. This term denotes properly such a portion of the space over which war prevails as has its boundaries protected, and thus possesses a kind of independence […] Such a portion is not a mere piece of the whole, but a small whole complete in itself. (Clausewitz [1832] 1950:162)

“Theatre of war” designates not only the literal space where the war is staged, but also the conceptual wholeness of war understood “as” theatre. Maneuvers are rehearsals; each rank demands specific role-playing; uniforms and medals are costumes; military parades are carefully rehearsed staged spectacles; battles, missile strikes, and air raids are choreographed movements of people, materials, and ordnance; intelligence and spying deploy deceptions often involving masquerades designed to create complex fictions, plots, and role-playing. At the dramaturgical level, war narrates a story of magnitude, conflict resolved by action, with a clear beginning, middle, and end: as neat a parallel to Aristotle as one can find. But also Shakespearean, as subplots proliferate. And performance art replete with improvisation and spectacular solo acts. If war is theatre, it is also a game played by opposing teams resolving themselves into winners and losers. The players, at least theoretically, obey the rules of the game, which are enforced, more or less, by international tribunals. War, both in its details and in its entirety, can be studied as a theatricalized Great Game. Once the curtain goes up, once the contest begins, the Great Game of war is its own engine of inevitability.

Or so it seems. The fact is that even such an engine of inevitability as the Great Game of war can be—and has been—postponed, as the Chinese did in the 1930s–’40s.

In 1927, the Chinese civil war began pitting the rebel forces of Communist Mao Zedong against the ruling Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek. In 1931, the Japanese conquered Manchuria creating Manchukuo, a puppet state. From that date forward, there were many skirmishes between Chinese and Japanese forces. By 1936, Mao recognized that the Japanese were an existential threat to China; and so he proposed to Chiang that they suspend their civil war and join forces against Japan. But Chiang wanted to eliminate the internal enemy, the communists, before fighting the Japanese. It took the “Xi’an Incident” of December 1936 to bring Chiang on board.Footnote 2 The Xi’an incident was when two of Chiang’s subordinates, Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng,Footnote 3 held Chiang captive until he agreed to suspend the civil war and join his nationalist army with the communists to fight the Japanese. This action was orchestrated by Zhou Enlai, Mao’s close associate and a former military academy classmate of Chiang. The agreement, called the Second United Front, worked out by Zhou and Zhang was finalized in August 1937. And just in time too, because after the July 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident, the Japanese launched a full-scale invasion of China, swiftly taking control of Beijing, Shanghai, and Nanjing.

The Second United Front stipulated: The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will cease conflict with the Nationalists (KMT); all CCP troops will be unified with the KMT army to combat the Japanese; the CCP will not circulate communist ideologies, politics, and propaganda within the national army; the KMT will not confiscate or seize CCP weapons; the KMT will free all CCP prisoners; after the Japanese defeat, the CCP and KMT will both dissolve their armies and the KMT will recognize the CCP as a legally legitimate party.

Figure 3. Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek in Chongqing, China, in September 1945, toasting the victory over Japan.

Did this momentous agreement to suspend the Chinese Great Game succeed? Yes and no. There were plenty of violations; trust between the communists and the nationalists was low; neither dissolved their armies once the Japanese surrendered in September 1945. As soon as the Japanese were defeated, the Chinese civil war resumed—and, to some degree, continues to this day. In 1949, Chiang and what was left of his army retreated to Taiwan where he and then his son, Chiang Ching-kuo, ruled Taiwan until 1988. The KMT remains a strong force on the island, which is still formally regarded by many as part of China. Mao and his successors rule the mainland and still officially designate Taiwan as a province of China. Only 13 nations and the Vatican recognize Taiwan as the independent Republic of China, the KMT rubric. Taiwan is not part of the UN.

What I want us to carry in our minds regarding the outcome of the Xi’an Incident and the Second United Front is that, imperfect as the agreement was, the combatants of a long and bitter civil war put their fight aside to face what they acknowledged was an existential threat to both of them. They realized that it would not matter who won their civil war if Japan conquered China. So they postponed their Great Game until the threat at hand had been dealt with. They suspended one war to fight another.

As the Ukraine war rages—a continuation, as I’ve noted, of the Great Game—the whole world lives under the existential threat of climate change and its consequences: rising oceans, super tropical storms, floods, heat waves, pollution, and species extinction. The Ukraine war, like all wars, produces vast amounts of greenhouse gasses, pollutes the land and air, and once reconstruction begins will further pollute because one pound of cement produces 9/10ths of a pound of CO2.Footnote 4 As a bulletin from the Sierra Club notes:

Armed conflict in cities not only displaces, kills, or gravely wounds civilians, the infrastructure necessary for the functioning of basic services is damaged or destroyed. Damage to wastewater and drinking water may lead to contamination of water resources. Explosions from rockets or fires generate huge volumes of debris and waste. The release of hazardous materials such as asbestos, industrial chemicals, and fuels compound the effects of environmental contamination. (Martinezcuello Reference Martinezcuello2022)

Another consequence of this war—of all wars—is the disruption of farming and trade, which leads to hunger and famine. War adds to the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change. In June 2022, the New York Times reported:

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia—two countries that were estimated to produce enough food to feed 400 million, and to account for as much as 12 percent of all globally traded calories—has made […] hunger considerably more acute. […] That worsening is the result of the war but the underlying crisis is both larger and more structural […]. Mostly thanks to Covid-19, climate change, and conflict […] 49 million people are on the edge of famine, 1.1 billion in extreme poverty, and 1.6 billion are experiencing food insecurity [of a global population of 7.9 billion]. (Wallace-Wells Reference Wallace-Wells2022:10)

Taking a broader perspective, Brown University’s Cost of War Project estimates that from the onset of its War on Terror in 2001 to 2022, the US’s war-related fuel consumption released 400 million tons of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere.

In the US at least, the Ukraine war has captured the attention economy: war reports, human interest stories, heroism, war crimes, pathos, destruction, heroes, villains, victims, strategic analyses, predictions, nuclear fears, NATO, Putin. I realize the war plays very differently in Russia, China, and North Korea, though even these bastions of unfree speech have a hard time reigning in social media even as they covertly propagate corrosive social media. And when the war is no longer “breaking news” as it settles into a routine and those selling ads consider it boring, there is a mass shooting, a Congressional hearing, a scandal … ABCC, “anything but climate change.” I watch from New York, but I assume this avoidance of climate change is widespread. That’s because climate change is too slow-moving to capture peoples’ attention except when a disastrous weather event happens—a cyclone, killer heatwave, out-of-control fire, flood, and so on. Even then, the catastrophe is presented more as the “hand of God” than as a direct consequence of human (in)action about climate change.

Indeed, climate change is not where the world’s attention is focused. This existential threat is both obvious and stealthy. Governments fail to meet even the modest goals of the Paris Accord while hoping for a deus-ex-technologia. The fact is, most people just want to get on with their lives, acting as if the future of the world will take care of itself. It’s enough to worry about Covid, the well-being of one’s family, pay the rent, and have a little leftover for a good time. There aren’t enough Greta Thunbergs. Even many suffering from inundation, fire, drought, cyclones, and so on, do not connect local weather to global climate. Climate change happens relatively slowly, like the frog in the pot hardly noticing the flame on the stove heating the water to boiling. Nor do most people connect species extinction due to habitat loss, exploitation, deforestation, desertification, and monocrop agriculture to climate change. Corporations pursue profits and sell their operations as progress. The struggle to own the attention economy, both as it plays out in media controlled by corporate monopolies and our consenting collaborative participation in it, is literally destroying the planet and its inhabitants.

In brief, the world cannot afford to play the Great Game, at least not in the way humankind—or should I more accurately say, “mankind”—has played it for millennia. The postponement of the Chinese civil war is a compelling model for how warring parties can work together temporarily to overcome an existential threat. The fact that Chiang had to be forced to recognize that the Japanese were an existential threat is key.

So if not the Great Game, what? The first step is for both ordinary people and the powers-that-be to recognize that climate change will deeply degrade human civilization, if not destroy it altogether, and recognize as well that climate change will also punish the nonhuman world. We are, I believe, well on the way toward this recognition. What’s lacking is devising and putting into action a global plan to slow and then reverse climate change. Kim Robinson in his 2020 The Ministry for the Future offers a well-researched plan ensconced in a utopian story. Robinson’s ideas are getting a lot of play,Footnote 5 but there’s a big gap between fact and fiction. There’s been plenty more lip-service than action; and thousands of hours of media hypocrisy sponsored by big oil and other against-doing-much actors. Turning that around depends on climate change getting its rightful share of the attention economy. Enough to galvanize governments and even corporate boards.

Figure 4. Berlin protests against the Ukraine War, 27 February 2022. Photo by Lewin Bormann. (Courtesy of Creative Commons)

If that happens, the next step, and it’s a giant leap, is to postpone all wars, the Great Game, declaring a worldwide truce so that humankind can focus on climate change and its linked catastrophes of species extinction and pollution. I say “postpone” and “truce,” not “end” because I do not think that our primate selves can stop struggling over territory, hierarchy, physical resources, and control of “values” (ideological resources). It is enough for all the world’s powers, corporate as well as governmental, to postpone the Great Game until humanity has dealt with the existential threat that will make all such gaming irrelevant. Once the Great Game is postponed, all warfare energy—and remember how creative making war has been—can be focused on the climate problem. How can this possibly happen? In my “Can We Be the (New) Third World” (2015) I argue that Jawaharlal Nehru’s 20th-century idea should be adapted for the 21st century:

Today, artists, activists, and scholars are a New Third World. Nehru’s Third World had a specific geographical location. Today’s New Third World is a proportion of people present everywhere with a majority nowhere. What unites the New Third World is a community of purpose, a mode of inquiry (the experimental […]), and a sense of being other. […] The New Third World is incipient, seeds, not yet fully self-aware. (2015:9)

It is time to become urgently self-aware. We of the New Third World must make our leaders realize that if enemies as bitterly opposed as Mao’s communists and Chiang’s nationalists could postpone their civil war, then we can and must stop playing the Great Game until the climate threat has been dealt with.

I propose resuming the Great Game after we “solve” the climate problem—but when war resumes let it be as virtual warfare, bloodless yet consequential. A suspension of Artaudian aesthetics-politics in favor of Brechtian aesthetics-politics that recognizes every human being as a player in a drama that heretofore has been controlled by governmental and corporate elites. You ask me, as I ask myself: Exactly how do we get from where we are to where we need to be? That enormous decisive question I cannot answer. Robinson’s narrative in The Ministry for the Future is one concrete proposal, even if it is also fiction (as the great war narratives mostly are).

Be that as it may, let’s make the giant leap. A crazy leap. The wars stop. The whole world focuses on the existential threat. There is of course some back-sliding, just as there was in China. But if the alternative is the disruption if not the end of civilization, along with the extinction of untold numbers of species, the challenge will be met. Then what? What will the Great Game be when play resumes?

Not warfare as we now perform it, harming people and nature. Instead, something virtual but consequential, like sports, or banking. A genuine “theatre of war” and global spectacle. Already we live lives of actual consequences governed by virtual systems. We go to restaurants, order and eat, then pay with a card. Ditto for just about everything else we do, from rent to travel to banking…just about everything. Barter and cash exist, but as nostalgic operations with cash swiftly fading away. Cash itself is an arrangement constructed of agreements to honor what paper and coin represent. As AI and algorithmic programming mature—already cell phones and the internet are effectively universal—and as we approach the singularity, when self-conscious digital entities reproduce themselves and evolve, we flesh humans will become increasingly entangled in an existence that is more about the movement of information than it is about interacting physical objects.

What if war is brought into this domain? What if war was waged with the same efficiency, based on the same assumptions? The historical development of warfare is of ever-increasing distance separating combatants, from hand-to-hand blades to rifles, cannons, air bombs, rockets, and now drones. What if drone warfare, which resembles video games in terms of operation, were to be made completely a game? Virtual battles in virtual space but with actual consequences: if you lose, you lose something specific in terms of control over territory and resources. At another level, warfare already deploys nonlethal virtual weapons: economic sanctions and cyberattacks, for example. At least some aspects of this virtual warring are available for viewing; more than that, actively marketed as a kind of entertainment, as was Waterloo (both the original and the reenactments) and the Battle of Bull Run. If warfare was once made for spectating, as well as for conquering, why not return to this classic mode?

Thus: nations, or whatever entities replace or act on behalf of nations, go to war. They use whatever virtual weapons they can—some already existing, some invented for the “war effort.” These range from stuff we are familiar with from countless virtual combat games to cyber weapons cloaked in various “dark operations”: manipulation of financial markets, supply chain disruptions, scrambling of navigation controls, disruption of the electrical grid, propaganda, deployment of internet memes, trolling, etc. Real stuff, but no combat with guns, tanks, bombs, drones, missiles, mortars. Yes, people probably will die in the chaos of a downed electrical grid and other disruptions. But the casualties will be orders of magnitude less than what is suffered from the bullets, cannons, rockets, and bombs of “traditional war.” Furthermore, virtual warfare will spare the habitat and not add greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere. The kind of New War I am proposing is governed by performance rules, a “great game” indeed, at least partly performed for a global public.

What’s decisive is that outcomes are binding. When an entity loses a battle, a virtual operation, the entity gives up territory, governance, and resources just as now happens in physical war. And as happens in sports and politics. Big money is involved in FIFA, the Olympics, and political campaigns. People try to bend the rules, game the Games, even cheat. But on the whole, the systems work. Most people trust the outcomes.Footnote 6 That is, we humans already live according to virtual realities. What I propose is that we bring our most self-destructive behavior into the shelter of virtuality. Of course, I have not worked this out—I do not know if it can be worked out—but the alternative is even more unthinkable: to continue playing the Great Game as we’ve been playing will end human civilization as we know it, destroy much animal and vegetable life, and scar the planet.

We are creatures who live in the mind of god. That is, we live in the imaginary. The higher our intelligence as a species evolves, the more imaginary our existence. Yes, we are physical too: we eat, excrete, laugh, talk, mate, procreate. But as humanity approaches the singularity, it converges on and becomes more solely imaginary: pure connectivity. Sooner or later the biophysical vanishes or lives alongside the self-reproducing digital intelligence. The advent of the digital is neo-Cartesian, a cogito of pure idea, a Platonic masterpiece. The computing electron is the new synapse; instead of the “word made flesh” the word makes itself. I am not sure this is a good thing; but it is taking place, “our place,” literally.

I am an intelligent being from another world. My field of study is earth human behavior. We who are not you, are placing our bets on what you will decide to do.