Toprakkale/Rusaḫinili Qilbanikai is located roughly 5 km east of the Van Citadel (Ṭušpa), the Urartian capital. The limestone natural hill on which the citadel stands is connected to Mount Zimzim behind it (Fig. 1). The citadel is 400 metres long on the north-south axis and 60–70 metres wide. The Urartian name of Toprakkale (Rusaḫinili Qilbanikai) is accepted to have derived from a tablet dating to the reign of Rusa (II?), son of Argišti (Lehmann-Haupt Reference Lehmann-Haupt1906: 105, Fig. 77a-b); however, there is an ongoing debate on whether the citadel was built by Rusa son of Argišti, or Rusa son of Erimena.Footnote 1

Fig. 1 Ṭušpa, the capital of Urartu and Toprakkale (A. Tan)

Toprakkale is a significant site as it is the location of the first archaeological excavations concerning Urartu. Within a century, it is supposed to have been excavated by Dr. Reynolds, Captain Emilius Clayton, Hormuzd Rassam, Carl Ferdinand Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt and Waldemar Belck, Iosif Abgarovich Orbeli and lastly by Afif Erzen. What attracted so many researchers to this site? What is the true relationship between the artefacts that were believed to originate from Toprakkale –and thereby attracted excavators – and the site itself? In this article, by using various documents from the Ottoman Archives, I will explore the Toprakkale excavations from the 1870s onwards, via a re-assessment of the early researchers who worked there and the various excavation periods, and through discussion of the confusion caused by artefacts reported to have originated in ToprakkaleFootnote 2 (Tables 1–2).

Table 1 The Correspondence about Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam

Table 2 The Correspondence about Carl Ferdinand Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt and Waldemar Belck

Toprakkale's Rise to Prominence: the Finds and First Excavations

Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam

In a book published in 1874 Garegin V. Srvandztyants mentions finds discovered above Toprakkale, in an area he calls the Zimzim cave, including stones, large pithoi, small pottery, copper (bronze?) chair fragments and a bronze figurine depicting a man sitting on a ram. Srvandztyants states that this bronze statue was taken to Constantinople (Istanbul) by the bishop of Edessa (Srvandztyants Reference Srvandztyants1874: 132–133).Footnote 3 Furthermore, in 1877 various bronze artefacts and objects said to have come from Toprakkale began to be sold on the international market. It is widely thought that these artefacts stimulated the interest of Austen Henry Layard, who was employed at the British Embassy in Istanbul at the time (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 3–5; Barnett Reference Barnett1954: 16–19; Piotrovsky Reference Piotrovsky1969: 17). Layard writes in a letter dated August 3rd, 1877 to Dr Birch that a man brought him Assyrian bronze artefacts found in the vicinity of Van, which he remarks appear to be fragments of a throne or a chest – one where a figure's arms are folded on his chest with lion claws. He compares artefacts found in Nimrud. He claims that the bronze or copper panel fragments and lion claws are reminiscent of the throne fragments discovered in Nineveh. He also mentions that some of the panel fragments contain Assyrian texts (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 3–5). It is highly likely that the group of finds Layard purchased in Istanbul and those Srvandztyants mentions are comparable. On visiting Toprakkale Rassam refers to an artificial hill much like those of the Assyrians (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 130). Rassam had asked both the Pasha of the province and Layard himself for permission to dig it, but was refused. Also Barnett notes that in Rassam's book (Rassam Reference Rassam1897), “the all-important point, the reference to the source of the bronzes, is there discreetly omitted” (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 5). It appears that the reason why Toprakkale was perceived to be an Assyrian settlement, and its subsequent excavation as such, is due to Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam's excavations in Mesopotamia.

It is often mentioned that Layard sent Rassam, with whom he had collaborated in his Assyrian excavations, to Van to investigate the place where the items he purchased came from (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 3–5; Piotrovsky Reference Piotrovsky1969: 17).Footnote 4 Rassam went to Toprakkale in 1877 with a stopover in Van (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 111, 130). He explored Assur (Qalat Šergat), Kalḫu (Nimrud) and Balawat (Imgur-Enlil) in 1878–79 and could not return to Van.

In 1879 Captain Emilius Clayton and Dr Reynolds are said to have carried out excavations in Toprakkale on behalf of the British Museum and Rassam is supposed to have continued these in subsequent years (Lehmann-Haupt Reference Lehmann-Haupt1931: 455). Clayton ended his work in Toprakkale after a small-scale excavation during which he found only a few iron spear and arrowheads (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 19). In 1880 the American missionary Dr Reynolds and the British Vice-consul in Van, Clayton, hastily excavated Toprakkale under the supervision of RassamFootnote 5 on behalf of the British Museum (Barnett Reference Barnett1972: 163). Clayton's letter to Layard, dated May 11th, 1880, serves as the first excavation report and site plan of Toprakkale (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 9–12, Fig. 5; Zimansky Reference Zimansky, Köroğlu and Konyar2011: 59–60) (Fig. 1) and is noteworthy in terms of understanding the time of the excavation, locations of finds, and related architectural remains. Clayton says that the excavation in Toprakkale began on March 3rd, 1880, in an area he refers to as A – he divides the citadel into two parts (A on the north and B on the south). We understand that he excavated a temple from “the most perfectly hewn blocks of a sort of trap rock of a dark grey colour”, his plan drawing, and subsequent excavations. In area B, he refers to rough-cut stone walls as well as ivory and bronze artefacts (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 9–12, Fig. 5).

Rassam left the responsibility of this excavation to inexperienced people and busied himself with his excavations in Nimrud, Kuyunjik, Balawat, and Assur. However, once the temple was discovered he returned to Van on July 29th, 1880 and carried out a short-term excavation in Toprakkale (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 378; Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 8, 17).

We understand from Rassam's own words that after the first destruction by Clayton, the second destruction of Toprakkale took place by his initiative. He divided the hill into three and dug tunnels from one end to the other looking for building remains: he perceived mud-brick architecture as rubble and earth, considering only the stone foundations worthy of keeping. The foundation of the temple and the three mosaic-floored rooms discovered on the southern slopes of the hill are worth noting. Other than various finds, the altar in front of the temple, seen in the only photograph of Toprakkale published by Rassam (Fig. 3), was later handed over to the Imperial Museum (Müze-i Hümayun) in Istanbul by Lehmann-Haupt.Footnote 6 Rassam refers to a plan when discussing the temple foundation as well as several other details but there is no information about this plan (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 378). However, his plan of the Ḫaldi temple was found subsequently in the British Museum with several other records in 1951 (Barnett Reference Barnett1954: 3, Fig. 1).Footnote 7 The many deficiencies and errors of this very debatable and destructive excavation left aside, scholars have emphasised that it made the first serious contribution to Urartian archaeology (Barnett Reference Barnett, Boardman, Edwards, Hammond and Sollberger1982: 316–317). Nonetheless, it is more pertinent to argue that rather than a significant contribution, Toprakkale created ambiguity and confusion in scholarship on Urartian archaeology. The level of destruction can be identified further by taking into consideration the height of the mud-brick walls immediately behind the temple (Fig. 3). Especially in the vicinity of the Ḫaldi temple, which is said to have been looted previously,Footnote 8 shields with cuneiform inscriptions, cauldrons, ivory artefacts, and bronze throne fragments were discovered (Barnett Reference Barnett, Boardman, Edwards, Hammond and Sollberger1982: 317). The bronze fragments mentioned by Clayton and Rassam, which were thought to belong to a throne, are open to discussion. They are different from those said to have been purchased by Layard.

Fig. 2 The sketch of Toprakkale drawn by Clayton (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 9, Fig. 5)

Fig. 3 The excavation of the Ḫaldi temple at Toprakkale (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 376–377)

It is possible that as early as 1860 Layard was aware of finds similar to those he purchased in 1877, which eventually triggered the excavations. At this point, two documents in the Ottoman Archives that are related to Layard are worth mentioning (Table 1). The first is the letter sent by the British Ambassador, Sir Henry Bulwer, to the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs on June 10th, 1860 (Fig. 4 = Document 1), in which the Ottoman Empire is praised for its contribution to Layard's work at Nimrud. The document also cautions about the protection of several artefacts said to have been discovered in the vicinity of Van, which primarily consist of “a bronze bull –one-third of the size of the animal– with a human head and a bull's body, one large eagle and two carved snakes”. In the letter, it is said that the governor of the province was unaware of the value of these artefacts and had some of them melted to make use of their metal – therefore a request is made that an order be sent to him in order to prevent the destruction of these artefacts.

Sublime Port's assistance to Monseiur Layard's research, which unearthed numerous ancient artifacts several years ago, has been appreciated by the British state. I will not hesitate to request the protection of some artifacts recently discovered around Van. Since ancient artifacts, consisting mainly of a bull made of bronze at one-third of the size of a bull and with the head of a man, a large eagle, and two serpents with carved surfaces, the value of which was apparently not understood by the governor of the land, the pasha, have reportedly been melted to utilize its metal; such artifacts should not be wasted anymore; an order should be written on this matter and sent to the pasha.Footnote 9

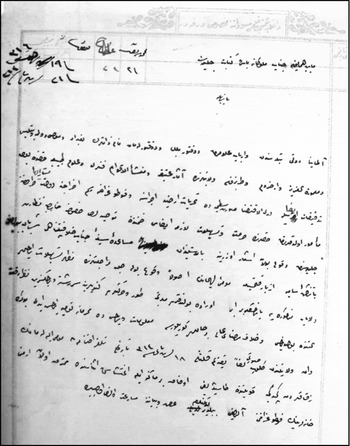

Subsequent to this letter, Seyid Mehmed Emin Ali sent a report to Kenan Pasha, the kaymakam (district governor) of Van, on August 6th, 1860 / 18 Muharrem 1277, which refers to the ancient artefacts (Asar-ı Atika) discovered recently by Layard in Van, stating that they were aware that several of the finds, which included a bronze bull, a large eagle, and two snakes, had been melted for their metal. The letter emphasises the local government's role in the protection of such ancient artefacts and encourages awareness of their value and of their ongoing destruction. The correspondence also states that subsequently discovered ancient artefacts should be safeguarded in a proper place (Fig. 5 = Document 2). These documents demonstrate the Ottoman Empire's approach towards ancient artefacts as early as the 1860s, especially in relation to their preservation.

It has been reported that some of the ancient artifacts that were recently discovered by British Monsieur Layard around Van, which had been left to the government, including a bull, a large eagle and two serpents made of bronze, were melted down to utilize their metal. It is not a right conduct at all for the local government to melt and destroy such ancient artifacts when they should protect them instead, since they do not understand their value. Ancient artifacts should be safeguarded in a proper place from now on.Footnote 10

These two documents thus may suggest that Layard knew of the bronze artefacts discovered in the vicinity of Van in 1860. Especially, the bronze bull, one-third of actual size, is among those found by Layard and left to the government as its share. It is not known, however, where these items were found. Layard, describing his excavation at the Treasure Gate/Analıkız, does not refer to any finds or artefacts (Layard Reference Layard1853: 399). The human-headed bull-shaped artefact calls to mind the human-headed and winged bull said to have been found in Toprakkale and purchased by Layard in 1877 (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 6, Plate 6). Considering that Layard was aware of bronze human-headed bull figurines as early as the 1860s suggests that he did not send Rassam to Toprakkale (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 111–130) only because he was curious about the origins of the items he bought in Istanbul. It is suggested that he knew the Van region and its geography well, and had found similar artefacts in Van before. We should especially keep in mind the possibility that Layard formed relationships with various teams in Van in 1849, while he was working there, or that he may have had them supervised.

Fig. 4 Document 1 (HR. MKT. 344/44, 18 Muharrem 1277 / August 6th, 1860)

Fig. 5 Document 2 (HR. MKT. 362/50, 18 Muharrem 1277 / August 6th, 1860)

There is correspondence showing that Rassam planned excavating other areas prior to his arrival in Van in 1877. He had applied for a permit to excavate and research ancient artefacts in the Diyarbekir province on behalf of the British on February 24th, 1877 / 10 Safer 1294, but his application was rejected. The reasons cited included that Diyarbekir was a large province consisting of several kazas and livas, and that the area called Assyria was located between Diyarbekir and Mosul, that Ceziretülarab and Diyarbekir were in opposite directions and quite distant, and that therefore the permit request was against the Law on Ancient Artefacts. The law stated that excavations could be conducted only within villages or districts, and that excavations could not exceed their boundaries,Footnote 11 therefore Rassam is primarily asked to define more precisely where he would be excavating.Footnote 12 In the correspondence of September 15th, 1877 / 7 Ramazan 1294 and November 22nd, 1877 / 16 Zilkade 1294, the British Ambassador Layard requests a research permit on behalf of Rassam to investigate Nineveh. The permit is grantedFootnote 13 on the condition that excavated finds should be shared between the government and Rassam, in accordance with the law.Footnote 14 Referring to Layard's previous explorations and research in Nineveh, Assyria and Babylon, in the correspondence of December 13th, 1877 / 7 Zilhicce 1294 and December 30th, 1877 / 21 Zilhicce 1294, a new permit is requested on behalf of the British Museum.Footnote 15

Rassam was granted a permit on February 14th, 1878 / 2 Şubat 1293 to explore ancient artefacts in Mosul.Footnote 16 A separate order clearly defined the rules to be abided by and the responsibilities of the officials who were to accompany the expedition. It stated in particular that the finds were to be recorded in two books. One of each of those artifacts that had duplicates or otherwise could be divided would be left to the Ottoman State. The prices of those artifacts that could not be divided would be defined by the local administration, and shared equally between the Ottoman State and the British Museum. For this reason, one notebook was to be kept by the official, and the other by Rassam – so that each item could be recorded daily, in terms of number and type – and signed by both parties.Footnote 17 A report sent to the priest Sebilyan Efendi, an official who accompanied Rassam, states that Rassam was carrying out research on behalf of the state and that the artifacts which would go to the State Treasury among the artifacts that he would excavate had already been identified, and therefore that he should be distinguished from other researchers and his research and explorations should not be unnecessarily hindered.Footnote 18 In a report dated May 11th, 1878 / 9 Cemazeyilevvel 1295, concerning staff salaries sent to the Sublime Porte, Rasssam is understood to be continuing his excavations in the vicinity of Mosul;Footnote 19 however, in a document dated October 17th, 1878 / 20 Şevval 1295, it is stated that Rassam had excavated in MosulFootnote 20 and that he was waiting for the renewal of the December 3rd, 1878 / 8 Zilhicce 1295 firman, given subsequent to Layard's request.Footnote 21 In a telegram sent to the Baghdad province on May 6th, 1882 / 24 Nisan 1298, it is noted that the Embassy had reported that Rassam's work was being hindered and that he should be treated in accordance with the firman.Footnote 22 Layard in particular expedited bureaucratic processes such as the excavation permits which were necessary for Rassam to carry out excavations and thus enabled him to continue work.

Layard and Rassam conducted excavations in several Assyrian settlements between 1877 and 1882. The prospects for Toprakkale were enhanced when in 1880 the province of Van was included in these excavations. A firman, dated August 16th, 1880 / 10 Ramazan 1297 and addressing the governors of Baghdad, Van and Aleppo, granted Rassam the permit – on behalf of the British Museum and Layard – to explore an extensive region that included also Van. It can be assumed that excavations in Toprakkale began after this date.

The British Embassy, in a correspondence dated December 15th, 1882 / 3 Kanunuevvel 1298, applied for the renewal of the permit. The correspondence notes that the firman dated August 16th, 1880 / 10 Ramazan 1297 and addressed to the governors of Baghdad, Van and Aleppo, which granted permission to Rassam for research on antiquities on behalf of the British Museum, had expired. Citing the hitherto fruitless communications of the Ambassador in this regard, the letter warns that unless the permit is renewed, this costly excavation will remain unfinished. Subsequent correspondence demonstrates that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Hariciye Nezareti) extended the duration of the permit based on the previous firman, on the condition that related regulations are abided by (Document 3 = Fig. 6).Footnote 23

Fig. 6 Document 3 (MF. MKT. 79/79, 4 Cemazeyilevvel 1300 / March 13th 1883)

A letter dated March 25th, 1884 / 27 Cemazeyilevvel 1301, however, contains another request for renewal of the firman dated August 16th, 1880 / 10 Ramazan 1297, which granted concessions to Layard for the exploration of ancient artefacts in Van, Aleppo and Baghdad. Stating that previous applications to the Sublime Porte had not amounted to any successful result, a new request is put forward for the renewal of Layard's permit and for the issue to be raised with the Sultan.Footnote 24

The renewal of the original permit of 1880 is a constant cause of correspondence between the Embassy and the Sublime Porte. There is a discrepancy, however, between the date of the permit issued to Layard, and the dates when Dr Reynolds and Captain Emilius Clayton, British Vice-Consul –charged with digging Toprakkale by Rassam – began their excavations. We have mentioned that in 1880 Clayton and Reynolds carried out a short-term excavation in Toprakkale under Rassam's supervision as he was digging in various Assyrian settlements (Barnett Reference Barnett1972: 163). Clayton, however, in a letter addressed to Layard on May 11th, 1880, states that he began excavating on March 3rd but had to stop within a few days owing to a number of factors including weather conditions (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 9; Zimansky Reference Zimansky, Köroğlu and Konyar2011: 59–60). As Clayton mentions, weather conditions would have made it unlikely to be able to excavate Toprakkale in March. The fact that the permit started in August rules out the possibility of earlier excavations and therefore Clayton's starting date becomes disputable.

K. Kamsarakan

An illegal excavation was carried out at Toprakkale following Rassam's excavation. The letter Reynolds penned to Birch on June 24th, 1884 from Van is significant in terms of the information it provides on this dig and the finds (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 20–21):

Yesterday a working man who has been doing some excavating on his own hook in the vicinity of the trenches Mr. Rassam opened when here, brought a bronze image in very perfect preservation. The body is that of a lion, with wings, but the rest of the body not feathered. To this is added a human head, shoulders and hands, the latter folded in front. The face is ivory. If you received my former letter containing the description and figures of images for sale here, this resembles one there figured but is a little smaller, about 7 inches (17.7 centimetres) long and 5 inches (12.6 centimetres) high.

Barnett identified the winged sphinx with the body of a lion mentioned in the letter as one of the bronze figurines in the Hermitage (Barnett Reference Barnett1954: 19), which was published by PiotrovskyFootnote 25 (Piotrovsky Reference Piotrovsky and Gelling1967: 28, Fig. 15). Piotrovsky relays an important acquisition recorded by F.G. Bernshtam in the Hermitage archives of 1885:

Sold to me for the Department of Antiquities of the Hermitage for 3,000 roubles the following Assyrian objects, to wit: 1 silver bracelet (with lion heads), 1 similar of bronze but broken, 1 bronze winged lion with human head of alabaster, 1 bronze goat with damaged face, 1 bronze staff end, 1 bronze ring, 1 piece of bronze armour, bronze fragments and several pieces of alabaster. All these found by Mr. K. Kamsarakan at Van on the hill of Toprakkale in 1884.Footnote 26

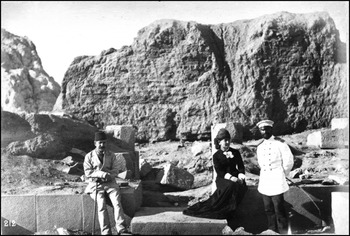

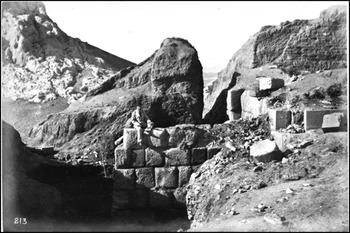

The winged bronze lion with an alabaster human head (inventory no: 16002) is identified as a sphinx, while the bronze goat with a damaged face is considered to be a winged bull (inventory no: 16001) (Barnett Reference Barnett1954: 19). Barnett also states that the identity of one of the people referred to in Reynolds' letter to Birch is likely to be some sort of a special attendant or employee, either Sedrak DevgantsFootnote 27 or Kamsarakan, the Russian consul in Van. Two photographs of Toprakkale dating to 1881 that we have discovered are extremely significant in this regard. The photograph of Mrs KamsarakanFootnote 28 with Mr. Gaillard, who was the chief of the international telegram service in Van, in front of the Temple of Haldi in Toprakkale demonstrates the Kamsarakan's interest in the site (Figs. 7–8).

Fig. 7 Mr. Gaillard and Madam Kamsarakan, in front of Ḫaldi Temple at Toprakkale (Chantre and Barry Reference Chantre and Barry1881: F. 22)

Fig. 8 Mr. Gaillard sitting on the wall of Ḫaldi Temple at Toprakkale (Chantre and Barry Reference Chantre and Barry1881: F. 21)

The “working man” referred to in Reynolds' letter to Birch, dated June 20th, 1884, may be associated with Devgants, who himself excavated near Rassam's trenches and unearthed a bronze statue, which was said to be in pristine condition. He was known to be an antiquities dealer who sold items abroad via places like AstwadzaschenFootnote 29 and DzevesdanFootnote 30 (Müller Reference Müller1885: 24; Müller Reference Müller1886: 158; Piotrovsky Reference Piotrovsky1969: 17). The artefacts Devgants claimed that he found in Toprakkale, his relationship with the Kamsarakans, and the fact that he was selling artefacts, make the context of the archaeological finds rather questionable.

Carl Ferdinand Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt and Waldemar Belck

Previous scholarship generally accepts that Lehmann-Haupt and Belck excavated at Toprakkale in 1898–1899 (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 23; Öğün Reference Öğün1961: 265; Piotrovsky Reference Piotrovsky1969: 19; Sekmen Reference Sekmen1990: 30; Wartke Reference Wartke1990: 8; Sevin Reference Sevin2003: 4; Salvini Reference Salvini and Aksoy2006: 18; Koçak Reference Koçak2011: 90–91; Tarhan Reference Tarhan, Köroğlu and Konyar2011: 295; Zimansky Reference Zimansky, Köroğlu and Konyar2011: 60–61). It is even suggested that they excavated over two consecutive seasons in 1898 and 1899 (Erzen et al. 1960b: 5). However, in their report to the Anthropologische und Ethnologische Gesellschaft Berlin, dated October 5th, 1898, Lehmann-Haupt and Belck state that they came to Van on September 24th (Belck and Lehmann-Haupt 1898: 416). In the same publication, in a report dated December 5th, 1898, they state that they reached Van on September 24th, 1898, and began preparing for the excavation a week later, on September 30th, 1898 (Belck and Lehmann-Haupt 1898: 578–579).Footnote 31 In a joint report penned on November 30th, 1898, they state that they had been excavating at Toprakkale for almost two months with 80 to 100 workers (Belck - Lehmann-Haupt 1898: 578). In his subsequent publication, however, Lehmann-Haupt gives December 30th, 1898 as the starting date of the excavation (Lehmann-Haupt Reference Lehmann-Haupt1931: 457). Considering the incredibly harsh winter conditions in Van, especially from December onwards and continuing well into March, it would have been impossible for them to carry out an excavation during this season. As this rather refutes the December date, it would be wrong to suggest that they arrived in Van and began excavating in December (Sekmen Reference Sekmen1990: 32; Sevin Reference Sevin2003: 4). It is necessary to study the relevant Ottoman correspondence on Lehmann-Haupt and Belck in order to clarify whether they actually excavated on that date, or whether indeed the excavation had been continuing for two months in December, and for how long they excavated and what the conditions were (Table 2).

We have found various documents concerning the excavations carried out by Lehmann-Haupt and Belck in 1898–1899, including permits, in the Ottoman Archives of the office of the Prime Minister. These documents cover the years between 1898 and 1902, but those that relate to 1898 and 1899 need to be scrutinized separately.

Dated April 7th, 1898 / March 26th, 1314 the earliest document is written in connection with a telegram sent from the German Embassy regarding Dr. Lehmann and Dr. Belck's impending explorations in Baghdad, Mosul, Van, Mamuretülaziz, Erzurum, Bitlis and Trabzon.

The document was sent to 14 provinces via the Interior, Foreign Affairs and Education ministries (Dâhiliye, Hariciye ve Maarif Nezareti) and instructed governors to aid Lehmann(-Haupt) and Belck in their pursuits. In the other two letters, dated April 13th, 1898 / 21 Zilkade 1315 and May 13th, 1898 / 21 Zilhicce 1315Footnote 32 and another dated May 9th, 1898 / 17 Zilhicce 1315,Footnote 33 the same content requesting help regarding the research they would carry out in 7 provinces is reiterated.

In a letter dated May 23rd, 1898 / 2 Muharrem 1316, Osman Hamdi Bey, the director of the Imperial Museum, informs the Education Ministry of the nature of this exploration. He emphasizes that Dr. Lehmann and Dr. Belck are allowed to investigate ancient artefacts, the origin of species, and natural sciences, and have the necessary permit to carry out surface surveys in the provinces of Baghdad, Mosul, Van, Bitlis, Mamuretülaziz, Erzurum and Trabzon. He especially notes the reports that were circulating about them intending to excavate, but that unless they met the requirements in the regulationFootnote 34 (Asar-ı Atika Nizamnamesi/Antiquities Law), they would not be in a position to do so (Document 4 = Fig. 9).Footnote 35 Both the Antiquities Law (Çal Reference Çal, Yalçın and Berikan Yayınları2005: 259–260) and the scope of the research permit granted to Dr Lehmann and Dr Belck clearly illustrates this situation.

Fig. 9 Document 4 (MKT. 397/1, 2 Muharrem 1316/23 Mayıs 1898)

Zühdü Pasha, the Education Minister,Footnote 36 in his letter dated June 11th, 1898 / 21 Muharrem 1316, states that 14 references (teveccühname) were sent to provincial governors, instructing them to facilitate Dr Lehmann and Dr Belck's explorations, who were charged by the German government with the investigation of ancient artefacts, the origin of species, and natural sciences, and carrying out surface surveys if necessary, and taking photographs. In view of the reports of their intention to excavate during their trip, it is stressed that this could only be carried out by meeting the conditions of the regulation, and that they only have the authority to carry out surface surveys. Also noted is that in the event that these reports are correct and excavation does take place, the necessary actions should be taken in order to comply with the regulation. The exact same issues are raised in a correspondence with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, dated June 12th, 1898 / 22 Muharrem 1316, that also instructs, in order to avoid future problems, all necessary measures to be taken in the event of a possible misuse of permit.Footnote 37

Subsequent correspondence between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Education, dating to July 2nd, 1898 / 12 Safer 1316, August 2nd, 1898 / 14 Rabiulevvel 1316, and August 4th, 1898 / 16 Rabiulevvel 1316, reiterate the problems that Dr Lehmann and Dr Belck's intention to excavate might create, and instruct the Ministry of Education to take the necessary actions in advance. A letter from the Ministry of Education on July 6th, 1898 / 16 Safer 1316, however, states that Dr. Lehmann and Dr. Belck's aim was to conduct surface surveys and that they would not attempt to excavate, and therefore, no further action was necessary.Footnote 38

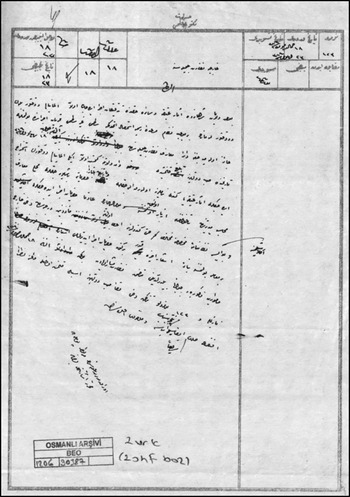

The letter from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, dated November 3rd, 1898 / 18 Cemazeyilahir 1316, presents crucial details on the history of excavations and attempts of excavation. It begins by stating that without an official permit Lehmann and Belck were not entitled to carry out investigations on ancient artefacts in the provinces at stake, and that it would be illegal for them to conduct any such pursuits. Referring to a telegram sent by the local Education Accounts Directorate, which informs of two German Doctors who are going to start excavating the following day and that they will be taking the artefacts they would unearth, the letter states that this is against the regulation as well as their permit, and that under no condition should an excavation take place without further instructions (Document 5 = Fig. 10).Footnote 39

Fig. 10 Document 5 (BEO. 1206/90387, 18 Cemazeyilahir 1316/3 Kasım 1898)

The governor of Van, Tahir Pasha, in a letter to the Ministry of Interior on November 30th, 1898 / 18 Teşrinisani 1314, shares some information he received from the police department. Using a small gadget that he was carrying on his chest, Dr. Lehmann was taking photographs of Armenian houses, burnt down during a conflict.Footnote 40 On another document dated December 3rd, 1898 / 19 Receb 1316, there are instructions for Dr Lehmann and Dr Belck to follow, and in the case of an issue this should be reported secretly. The letter also asks about the necessary measures regarding the photographs Dr Lehmann took (Document 6 = Fig. 11).Footnote 41

Fig. 11 Document 6 (DH. MKT. 2143/16, 19 Receb 1316/3 Aralık 1898)

The governor of Mosul, Hazim Pasha, in a letter to the Ministry of Education on May 2nd, 1899 / 20 Nisan 1315, refers to four inscribed stones, which Monsieur Lehmann, had unearthed by himself from the Nimrud ruin, and was in the process of transporting them. In a letter sent to the governorship of Mosul on May 6th, 1899 / 25 Zilhicce 1316, it is emphasized that Dr Lehmann and his companion's permit only allows for surface surveys, and as this does not give them the right to excavate or transport artefacts, the governorship is instructed to confiscate the items and keep them under protection at the governorship and send their photographs to the Ministry. The letter specifically emphasizes that excavations are subject to official permits in accordance with the regulation, and therefore excavations without permits should be prohibited. In another letter sent to on May 6th, 1899 / 25 Zilhicce 1316, Mehmet Tevfik the Deputy Education Director of Mosul informs the Ministry of Education that Dr Lehmann and his companion had excavated at Nimrud and that four inscribed artefacts were about to be transported, but that the stones were confiscated by the governorship and the actions of these two persons were reported in detail in two telegrams sent to the Minister of Education and the director of the Imperial Museum. A letter sent to the High School (Mekteb-i İdadi) Directorate of Mosul on July 4th, 1899 / 22 Haziran 1315, gives instructions not to let Dr Lehmann and his companion Belck excavate without a permit, and to inform the local government immediately in case foreigners or locals excavate for artefacts.Footnote 42

In a letter dated September 5th, 1899 / 28 Rabiulahir 1317, there are specific instructions not to let anyone excavate for ancient artefacts without a prior permit – based on the information obtained from the governorship of Mosul, which informs about Dr Lehmann and Dr Belck's illicit excavation at Nimrud during which they unearthed four stones and brought them to Mosul.Footnote 43

Lehmann-Haupt's investigations on May 23th, 1899Footnote 44 at the Lice-Tigris tunnel is the subject of a ciphered message sent from Diyarbekir on June 5th, 1899 / 24 Mayıs 1315, which states that Dr. Lehmann and the Russian consul in Van met at the caves in the vicinity of Lice (Tigris tunnel) and on the 16th day of the month, on a Sunday morning, went to Çapakçur (Bingöl), in the Genç sancak of the province of Bitlis, and that Dr. Lehmann took photographs and copied the images and inscriptions at the entrances of two caves (Lehmann Reference Lehmann-Haupt1901: 226–244, Fig. 1–4).Footnote 45 Another letter reports the departure of Dr Lehmann and Dr. Belck from Van on February 14th, 1900 / 2 Şubat 1315, and their arrival in Cizre on March 14th, 1900 / 1 Mart 1316, via Gevaş, Karçikan, Bitlis and Siirt, and states that Dr. Belck returned to Van and Dr. Lehmann travelled to Erzincan, stopping at Midyat, Lice, Palu, Mazgirt, Harput, Malatya, Eğin, and Kemah.Footnote 46

All of the correspondence examined reveals explicitly and recurrently that the permit given to Lehmann-Haupt and Belck was for the investigation of ancient artefacts, the origin of the species, and natural sciences, which if necessary could involve surface surveys and photography, in seven provinces including Baghdad, Mosul, Van, Mamuretülaziz, Erzurum, Bitlis and Trabzon. Lehmann-Haupt and Belck, on the other hand, legitimize their actions in Toprakkale by stating that they interpreted the permit in the sense of “oberflächlich ausgraben” (surface excavation) (Belck and Lehmann-Haupt Reference Belck and Lehmann-Haupt1898: 578). The documents we have introduced above, however, especially those covering the years of 1898 and 1899, clearly state that the permit they had was actually, in today's terminology, for surface surveys, that it was under no circumstances an excavation permit, and that any infringement would cause problems. These documents also plainly demonstrate contrary to previous statements (Sevin Reference Sevin2003: 5) the Ottoman State's interest in archaeology, excavations and ancient artefacts, and its control mechanisms in distant provinces of the empire.

The dates Lehmann-Haupt and Belck refer to in relation to their excavation need to be revisited based on these documents. In their report dating November 30th, 1898, Lehmann-Haupt and Belck mention that they had been excavating for the last two months with up to 80–100 workers, but in the reportFootnote 47 of November 3rd, 1898, it is stated that that they will begin excavating the following day and doing so would be against the regulationFootnote 48 and outside the scope of their permit, and therefore they should not be in any way allowed to excavate. The “following day” in the report should refer to November 4th, 1898, in which case it would not have been possible for the explorers to excavate during the previous two months.

It is clear from the correspondence the two explorers were closely followed and periodically reported on by the state officials during their work in the region. In the correspondence of 1898 and 1899, it is specifically noted that they were not allowed to excavate and that the situation should not become a problem. The Ottoman State knew about a small gadget Lehmann-Haupt was carrying on his chest, so it is highly unlikely that it was not aware of an excavation continuing in the midst of Van for almost two months with 80–100 men and had permitted that excavation – and the correspondence above fully reveals the situation. Bearing in mind the fact that Belck was injured near AdilcevazFootnote 49 and that therefore all eyes were on these two explorers make it all the more implausible for them to have been carrying out an excavation at Toprakkale for two months in spite of the various cautions and reports, and therefore the subject remains controversial. Nevertheless, it is still a possibility for them to have performed an illicit excavation through their connections with local people such as Mkrtitsch Maksapetian.Footnote 50 We know from the above correspondence that they had indeed carried out an illicit excavation at Nimrud.Footnote 51 It is understood that Lehmann(-Haupt) and Belck had been in Nimrud and Diyarbekir from the spring of 1899 onwards, therefore it would not have been possible for them to implement an excavation in Toprakkale.

It is clear that Lehmann(-Haupt) and Belck did not excavate at Toprakkale in 1898–1899 with firmans from Istanbul (Sevin Reference Sevin2003: 4). To infer that their excavations, considered as a significant milestone in the Urartian studies, were performed meticulously, and to define them as the first scientific study on the subject would be erroneous. The site has not provided new or rich data on Urartian culture and history (Salvini Reference Salvini and Aksoy2006: 18). Certain other issues call us to reconsider Lehmann and Belck's activities at Toprakkale, such as the fact that they reveal little on the archaeological context (Zimansky Reference Zimansky, Köroğlu and Konyar2011: 60–61), they do not publish an architectural plan, and also the discrepancies surrounding the dates they excavated as well as the lack of an excavation permit. Although many other artefacts were published in subsequent years, they did not publish any plans of the site.Footnote 52 The only drawing relevant to Toprakkale is the one where the Van Citadel and its vicinity are depicted (Fig. 12), in which the site is roughly sketched (Lehmann-Haupt Reference Lehmann-Haupt1931: II/2). Barnett finds it peculiar that, like Rassam, Lehmann-Haupt did not publish any plans showing the site or its buildings, and remarks that all the information on Toprakkale relies on a single photograph Rassam published in his book (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 376; Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 13). Aside from Rassam's plan of the temple, Clayton and Lehmann-Haupt's sketches are far from providing insight into the architectural layout of Toprakkale.

Fig. 12 The sketch of Van Citadel and Toprakkale drawn by Lehmann-Haupt (Lehmann-Haupt Reference Lehmann-Haupt1931: II/2)

Iosif Abgarovich Orbeli

It is said that Orbeli excavated at Toprakkale in person in 1912 and discovered various items. Only a short report exists on his work (Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 25–26; Barnett Reference Barnett, Boardman, Edwards, Hammond and Sollberger1982: 318). It is most likely, however, that he began his excavation in 1911. He made his permit application for his explorations in Van on May 15th, 1911 / May 2nd, 1327 and in a response letter, dated June 1st, 1911 / 3 Cemaziyelahir 1329 there are instructions for his work to be facilitated.Footnote 53 The short reports on this excavation note the actual date of the excavation.Footnote 54

Afif Erzen

After a long hiatus, a team led by Erzen began excavating at Toprakkale in 1959 (Erzen Reference Erzen1960: 716–718; Erzen, et al. Reference Erzen, Bilgiç, Boysal and Öğün1960: 5–22) and continued until 1963 (Erzen Reference Erzen1961: 526–528; Erzen, et al. Reference Erzen, Bilgiç, Boysal and Öğün1961: 33–35; Erzen Reference Erzen1962: 623–624; Erzen Reference Erzen1963: 541–542; Erzen Reference Erzen1964: 568–572; Erzen Reference Erzen1967: 53–64). Erzen directed a second period of excavations in 1976–77 (Erzen Reference Erzen1977a: 1–59; Erzen Reference Erzen1977b: 58–59; Erzen Reference Erzen1977c: 622–623; Erzen Reference Erzen1978a: 1–15; Erzen Reference Erzen1978b: 539–540; Erzen Reference Erzen1980: 45–58; Erzen Reference Erzen1981: 69–70). By that time, after the excavations of the British and the Germans, there was not much left at the Temple of Haldi, other than several courses of stone (Figs. 13–15).

Fig. 13 Toprakkale (K. Işık)

Fig. 14 Toprakkale and foundation beds (K. Işık)

Fig. 15 Stones remaining from the temple area (K. Işık)

The early years of the excavation were spent cleaning the rubble and ruins of previous excavations, and surveying the square foundation plan of the Temple of Haldi (13.80mx1380m) (Erzen Reference Erzen1962: 402). As with the temple in Aznavurtepe (Boysal Reference Boysal1961: 200–201), 20×20 cm square pits cut 3–4 cm deep into the bedrock were useful in retrieving the ground plan of the temple. Afif Erzen's work concentrated on the temple, a storage building and related chambers. There is no reference to any fortification or palace building.

Excavated five times within a century, it is the subject of another debate as to how much remains of the citadel of Toprakkale, considered to be the start of Urartian archaeology (Figure 14). Contemporary photographs, foundation pits on the bedrock, and some scattered blocks in particular display this situation (Figures 6–8). The lack of a foundation inscription of the citadel makes it all the more difficult and questionable as to when and by whom it was founded.Footnote 55 Both Clayton and Rassam refer to basalt blocks in their descriptions of the temple. Rassam finds it unnecessary to send one to the British Museum, saying they are “bulky” and without any inscriptions (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 378). Figures 2–4 shows the entrance to the temple and the dispersed stone blocks. The fact that there are no inscribed stones at this location is peculiar when compared with other Urartian temples of other citadels.

Conclusion

Architectural fragments of Toprakkale, especially the finds collected in legal and illegal excavations carried out in the 1870s in the Haldi temple, can be found in various museum collections across the world. They attracted attention on the antiquities market from early on, resulting in more excavations, which ultimately contributed to the destruction of the site.

The figurines and fragments, considered to belong to a throne in Toprakkale (Srvandztyants Reference Srvandztyants1874: 132–133; Barnett Reference Barnett1950: 43; Merhav Reference Merhav1991: 254–255; Seidl Reference Seidl1994: 67–84; Seidl Reference Seidl, Herrmann and Parker1996: 185–186; Seidl Reference Seidl2004: 44) have no parallels in other Urartian period temples. The finds were dispersed to different locations and their context remains unclear. It is hardly likely that these fragments, some obtained through purchase, would belong to a single throne. Not only the excavations of that period are shady but also the supposition that fragments of the same throne were unearthed by different people in a temple that has been excavated numerous times is rather dubious. They can be decorative pieces of other objects obtained or purchased elsewhere.Footnote 56 Uncertainty looms over the exact location of where these furniture fragments were discovered, and they hardly seem to belong to a throne (Çilingiroğlu Reference Çilingiroğlu, Delemen, Çokay-Kepçe, Özdizbay and Turak2008: 341–346). It is similarly difficult to envisage Toprakkale,Footnote 57 devoid of any inscriptions on the temple (Rassam Reference Rassam1897: 378), as a capital (Burney Reference Burney1957: 42; Erzen Reference Erzen1967: 53–54; Burney - Lang Reference Burney and Lang1971: 162; Zimansky Reference Zimansky, Çilingiroğlu and Darbyshire2005: 237). In view of the destruction of Muṣaṣir, we should, nevertheless, consider that the Urartian kings may have needed a centre in which to carry out cult rituals and coronation ceremonies much like at the Haldi temple in Muṣaṣir (Sevin Reference Sevin2006: 147; Sevin Reference Sevin2012: 103).

Examination of the excavation periods of Toprakkale reveals conflicting results. The first known excavation in Van is known to have been somewhere other than Toprakkale. Layard, who came to Van in 1849, carried out a short excavation at the Treasure Gate/Analıkız, on the northeastern slope of the Van Citadel (Layard Reference Layard1853: 398–399) but he does not refer to any finds. We understand from archival documents that Layard knew of “a bronze bull –one-third of the size of the animal– with a human head and a bull's body, one large eagle and two carved snakes” before 1860 and that he somehow got hold of them in the vicinity of Van. Therefore, Rassam's dispatch to Toprakkale by Layard cannot have been solely on the basis of the purchased bronze artefacts, which demonstrate a striking resemblance to the artefacts said to have been discovered in Toprakkale. Layard's relationship with people like Devgants or Srvandztyants, who collected artefacts in Van, paid for illicit excavations and sold the discovered items abroad, should be kept in mind. Hyvernat's desire to purchase a bronze shield from Toprakkale (Müller-Simonis and Hyvernat Reference Müller-Simonis and Hyvernat1892: 193–194) further demonstrates that Toprakkale served more as a place to obtain artefacts than an archaeological excavation.

The date of Layard's permit (August 16th, 1880) and the date when Dr Reynolds and Captain Emilius Clayton, the British Vice-Consul, who were charged with digging Toprakkale, began their excavations show a discrepancy. In his letter to Layard dated May 11th, 1880, Clayton states that work began on March 3rd, which, in view of the August-dated permit, makes the excavation controversial. The same goes for Lehmann-Haupt and Belck. Reports covering the years 1898 and 1899 (Table 2) establish that their permit was in fact, in today's terminology, a survey permit, and demonstrate that they were allowed to carry out research in Baghdad, Mosul, Van, Mamuretülaziz, Erzurum, Bitlis and Trabzon, but that it was under no condition to be viewed as an excavation permit, and that any violation in that regard would cause problems. It is specifically emphasised that they were not allowed to excavate. It is clear that Lehmann-Haupt and Belck's work in the region had been closely monitored by Ottoman agencies. To think that they excavated close to the centre of Van for two months with about 100 people without the knowledge of the Ottoman State or that the state allowed them to do so is quite improbable. According to the reports of October 23rd, 1898 and November 15th 1898, the events following Belck's injury near Adilcevaz drew attention to these two researchers. Lehmann-Haupt's various travels in October, including to Keşiş Lake on October 13th, 1898 (Lehmann-Haupt Reference Lehmann-Haupt1926: 40), Astwadzaschên/Çavuştepe on October 27th, 1898 (Lehmann-Haupt Reference Lehmann-Haupt1926: 60), and further investigations in the same region on October 29th -30th, 1898 (Lehmann-Haupt Reference Lehmann-Haupt1926: 67–69) demonstrate that he was not in Toprakkale during that month. His investigations on the Minua Canal from November 13th onwards also show that he was not present at the site. Lehmann-Haupt continued his surveys during those months. His and Belck's dates do not match one another either. While the report dated November 30th, 1898Footnote 58 states that the team had been excavating at Toprakkale for two months, another report dated November 3rd, 1898 gives the next day as the starting day of the excavation. Ottoman documents, on the other hand, emphasise that the situation is a breach of the Antiquities Act (1884 Nizamname) and that they should not be allowed to start an excavation under any circumstances. It remains unclear how they could excavate for two months, in spite of these warnings and reports, Belck's injury and Lehmann-Haupt's travels in the region. The entire issue is controversial.

Other reports covering the months of May, July, and September 1899 state that they had been illegally excavating in Nimrud while possessing only a survey permit, and that this permit did not grant them the uncovering and transportation of artefacts. The local authority was instructed to confiscate the items, and keep them safe at the governorship, and to send their photographs. They were also reminded that excavations were subject to permits and that they should not be allowed to remove artefacts or to excavate without obtaining a permit first. Lehmann-Haupt and Belck's work near Mosul in 1899 does significantly prove their absence from Toprakkale during that period. Their investigations in seven provinces and their illicit excavations were immediately reported or prevented. But the presence of people like Devgants, Maksapetian and Kamsarakan, who collected artefacts in the Van region and put them up for sale on the antiquities market is known. As with Layard, Lehmann-Haupt's relationship with them should be considered.

The complexity that began with the excavation periods of Toprakkale, which was dug by Dr Reynolds, Captain Emilius Clayton, Hormuzd Rassam, Iosif Abgarovich Orbeli and Afif Erzen, continues with the controversy over the finds. It is highly likely that the artefacts believed to be unearthed at Toprakkale created a Toprakkale market, which meant that a diverse range of artefacts unearthed elsewhere in the area began to be sold as Toprakkale goods. This site, considered to be where Urartian archaeology began, has only exacerbated issues relating to the period of Rusa, son of Erimena.

Abbreviations

- HR. MKT.:

Hariciye Nezareti Mektubî Kalemi

- BEO.:

Bab-ı Ali Evrak Odası

- DH. MKT.:

Dahiliye Nezareti Mektubî Kalemi

- DH. ŞFR.:

Dahiliye Nezareti Şifre Kalemi

- HR. TO.:

Hariciye Nezareti Tercüme Odası

- İ. DH.:

İrade Dahiliye

- İ.HR.:

İrade Hariciye

- MF. MKT.:

Maarif Nezareti Mektubî Kalemi

- Y. PRK. UM.:

Yıldız Perakende Umumi

- Y. PRK. EŞA.:

Yıldız Perakende Evrakı Elçilik, Şehbenderlik ve Ataşemiliterlik