Arthur Trystan Edwards (1884–1973), seen in a youthful studio portrait in Fig. 1 and a later cartoon in Fig. 2, was a significant critic of architecture, planning and the built environment in twentieth-century Britain, particularly during the interwar decades.Footnote 1 His career was largely devoted to the interpretation and defence of ‘civic design’, a new hybrid practice that combined architecture and planning under the supervision of the architect. While this approach to urban development gained increasing traction in architectural and planning discourse, it has remained marginal in historical accounts of the period; Edwards, as a champion of this seemingly peripheral practice, has remained an elusive figure. Although some of his ideas were familiar to generations of architects and planners before and after the Second World War, the lack of a focused account of his writing (hindered by the absence of a substantive archive) has left his trace to grow fainter and fainter. What follows here is a critical introduction to the core of his architectural thought — his principles of civic design — drawing on his published writings as a critic, housing campaigner and consultant planner.

Fig. 1. Studio portrait of Arthur Trystan Edwards, Owen, Merthyr, c. 1918 (Cardiff, Glamorgan Archives, DXQN/25/14)

Fig. 2. Cartoon of Arthur Trystan Edwards, reproduced from ‘Personalia IV. Mr A. Trystan Edwards, MA, ARIBA’, Architectural Design and Construction (September 1931), p. 469. The papers being trodden underfoot ridicule Mendelsohn and Le Corbusier

The first part of the article introduces the idea and practice of civic design, interwoven with an account of Edwards's intellectual formation. His critical project sought to reintegrate ethics and morality into the design of buildings and cities and, crucially, into the practice, roles and responsibilities of the designer. These responsibilities were made all the more urgent by the needs of post-war societal reconstruction, particularly the needs of ‘the public’ or ‘average man’, which is discussed in the second section of the article. The third section explores the connection between ‘manners’ and ‘urbanity’ in Neo-Georgian design principles. Edwards understood these qualities not just in relation to civic or public architecture, but also in relation to domestic architecture within a holistic conception of the city. His critique of civic design married the civic and the domestic in a forcefully pro-urban perspective that ran counter to contemporary planning orthodoxy derived from the Garden City movement among practitioners, policy-makers and theorists. A bias towards suburbanising principles has continued to colour interwar housing historiography, though a new focus on mid-century urbanism and urbanity (in the work of Elizabeth Denby, Thomas Sharp, Frederick Gibberd and the Camden Architects Department, for instance) shows the prescience and influence of Edwards's critique.Footnote 2 The fourth and final section of the article traces the evolution of his housing criticism up to the launch of his campaign for a ‘Hundred New Towns for Britain’ in 1933. This concluding section lays the foundations for a more nuanced study of the Hundred New Towns Association in relation to the early history of twentieth-century low-rise, high-density development.Footnote 3

CIVIC DESIGN

Trystan Edwards was born in Merthyr Tydfil and attended Clifton College in Bristol before studying mathematics and Literae Humaniores (which at that time included contemporary philosophy as well as classical literature) at Hertford College, Oxford, from 1904 to 1907. After Oxford, Edwards worked briefly at the Morning Post, reviewing literature, although he soon became dissatisfied with a career in journalism. Between 1907 and 1910 he took up articled pupillage with Reginald Blomfield, to whom he referred reverentially as ‘the master’.Footnote 4 Having failed to enter the Royal Academy Schools, he enrolled at the Liverpool School of Architecture to study civic design in 1911.Footnote 5 This experience was to have a profound effect on his attitude to architecture and planning.

The phrase ‘civic design’ was coined by the charismatic head of the Liverpool School, C.H. Reilly, to propagate a new planning philosophy and practice. It was intended to contrast with nineteenth-century principles of urban development that reflected a laissez- faire individualism and an absence of robust planning regulation. Civic design emphasised the hybridity of the architect-planner at a time when the growing division of labour in the construction industry threatened the profession's superintending role. Through the patronage and engagement of the industrialist William H. Lever, later Lord Leverhulme, Reilly secured funding for a chair of civic design at Liverpool along with a publication to promote its research and views, Town Planning Review.Footnote 6 S.D. Adshead was appointed the first professor of civic design in 1909 and was assisted by Patrick Abercrombie, who also edited the Review and succeeded him in the chair from 1915. The department offered taught courses in the new subject and Edwards was among the first generation of students at Liverpool to gain a diploma in civic design in 1913.Footnote 7

At Liverpool, civic design combined a Georgian tradition of urban improvement with a Beaux-Arts education, inflected by American classicism. This tradition promoted a formal, axial and often monumental compositional manner for the layout of buildings, streets and open spaces. In that regard, the Liverpool School's new course was intended to test some of the assumptions of Garden City planning — a cause taken up enthusiastically by Edwards. The international RIBA Town Planning Conference held in London in 1910 had exposed the growing fissure between civic design advocates such as Reilly and Adshead, who argued for grand, formal, axial planning, and Raymond Unwin and the ‘parochial, insular ideals of the Garden City movement’, which espoused relatively informal, semi-rural planning in largely new satellite settlements or suburbs.Footnote 8 Some accounts of civic design have overemphasised the division between these two emerging schools of thought, which in fact shared a fundamental critique of the Victorian city and had common intellectual origins. The Garden City movement was itself a ‘heterogeneous collection of different groups and interests’.Footnote 9 Collaboration across ideological divides was, in any case, common and sometimes necessitated by public projects and other governmental initiatives such as London County Council's Charing Cross Bridge Advisory Committee (1930–31), which included both Unwin and Blomfield.Footnote 10 The London Society and the committees of the RIBA in the 1930s likewise accommodated both Modernists and traditionalists of various bents.Footnote 11

Nonetheless, civic design stood for a set of ideas contested at a national as well as international level. It was representative of a pan-European and transatlantic movement of Stadtbaukunst or ‘civic art’. Although later traduced by Modernist opponents, this ‘comprehensive and sophisticated framework’ grappled seriously with the problems of refashioning the city, especially in the context of democratic statehood.Footnote 12 It was also obviously indebted to American ideas, particularly Charles Mulford Robinson's writings and the City Beautiful movement.Footnote 13 In political and social terms, it was progressive — an ‘abstract device for expressing a unified civic consciousness’ to which many Liberals and Socialists especially in Lancashire, such as Lever and Reilly respectively, subscribed.Footnote 14 Edwards, a Fabian in his Oxford days, was doubtless also sympathetic to their ambitions.Footnote 15

After leaving Liverpool, Edwards took up work with the firm Richardson and Gill in London. Albert Richardson, who had been in F.T. Verity's office, was paying closer and closer attention to Georgian detailing, having published London Houses from 1660 to 1820 in 1911, which he followed with Monumental Classic Architecture in 1914, the year after Edwards left his office.Footnote 16 Edwards's intellectual formation was, therefore, clearly tied to contemporary interest in the classical tradition. Blomfield's ‘Grand Manner’ was an influence on Reilly and the Liverpool School, and Richardson's works were widely read.Footnote 17 Moreover, all three of these formative influences — Blomfield, Reilly and Richardson — were or were becoming accomplished writers with journalistic connections, and so it is unsurprising that Edwards cut his teeth in the architectural press early in his career. In 1914, he began to establish his name through a number of editorials and articles in the trade press, although this activity was curtailed by war. These pieces show a debt to Richardson's interest in Continental and English classical architecture and were published in the Architects’ and Builders’ Journal, of which Richardson became editor in 1919.Footnote 18

Edwards returned from the First World War, having served with a ‘hostilities only’ rating in the Royal Navy from 1915, and qualified as an associate member of the RIBA with a distinction in town planning in 1919.Footnote 19 He joined the Local Government Board, soon to become the Ministry of Health, as one of nine ‘temporary assistant architects’ involved in the nascent state housing scheme led by Unwin.Footnote 20 Lord Greenwood, a housing minister in Harold Wilson's first administration who knew Edwards later in life, recalled that ‘For several months he and Unwin ran our public housing programme almost single-handed’.Footnote 21 In fact, Edwards was a peripheral figure and did not enjoy the experience — he wrote to the planner Thomas Sharp in 1933 with regret that ‘on my return from the War I made the great blunder of entering the Housing Department of the Ministry of Health’.Footnote 22 We do not know the specific circumstances of Edwards's departure from public service after six years in the ministry, although it is likely that he was frustrated by, and out of kilter with, Unwin's political clout and the growing policy consensus around him. His departure was also almost certainly pragmatic — the government housing campaign was coming to a premature end in the early 1920s, and Edwards was doubtless seeking new opportunities anyway. Architectural criticism and journalism were his main outlets thereafter, and he published his first book, largely written before and during the war, in 1921. The Things Which Are Seen: A Revaluation of the Visual Arts contained lengthy explanations of his coalescing critical precepts.Footnote 23

FORM, SUBJECT AND THE AVERAGE MAN

The basis of Edwards's principles of civic design, buried in the rambling and sometimes obscure theses of The Things Which Are Seen, was the distinction between ‘subject’ and ‘form’. The conflation of the socio-political or ethical purposes of design and preconceived idealist notions of form had led, in the view of Edwards and many of his contemporaries, to a number of fallacies not only in architectural criticism, but in design itself. Edwards sought to distinguish these two aspects from each other and then recalibrate their relationship for architectural design and city planning.

‘Form’, in short, was the manner of composition and the appearance of ‘things’ (objects, buildings, beings, and so on), and by ‘subject’ was meant the purpose to which the design of these ‘things’ was aimed. The forms resulting from civic design were subject to the social welfare needs of the community. Both of these aspects had equal importance, interdependent yet conceptually distinct. Good design necessitated that the two be in close harmony, and good criticism was predicated on the ‘ability to distinguish between these elements’.Footnote 24 They also served as ciphers for the aesthetic and the ethical, and to Edwards these were profoundly integrated. This differed from the prevailing, Ruskinian, view that some forms were intrinsically good and others bad, and that certain social ideals (for instance, the Morrisian notion of craftsmanship — joy in labour) were innate to the good.

Edwards began his book with an anecdote about hearing a verse from a preacher who ‘ever and again […] took occasion to tell the audience that it was a cardinal error to attach much importance to “the things which are seen”’.Footnote 25 This was an allusion to and inversion of the meaning of the biblical verse:

While we look not at the things which are seen, but at the things which are not seen: for the things which are seen are temporal; but the things which are not seen are eternal (II Corinthians 4.18).

Edwards was arguing that, in fact,

‘The Things Which are Seen’ are patent, and to a shallow mind they appear to be but surface; yet the surface is a symbol and the symbol is profound. As they represent what is ultimate and essential, in such lie the past, the present and the future. If we stand aloof from them we deny ourselves access to the Spirit, for among ‘The Things Which are Seen’ the Spirit has its home.Footnote 26

Edwards's aesthetic theory was thus as much about perception (and Christian spirituality) as it was about taste. The world is constituted of objects and matter — things — with inherent meaning and significance, independent of consciousness, and human perception is thus a predetermined communication between meaningful and deliberate outward appearance and the mind. Edwards almost certainly derived this anti-idealist view of perception from his undergraduate education, during which he must have come under the influence of the Oxford Realists led by John Cook Wilson and his disciple H.W.B. Joseph at New College, and from his long-standing interest in Nietzsche, who ‘alone concerned himself primarily with the need to change and to imbue with the highest degree of spirit the solid three-dimensional world made known to us through our senses’.Footnote 27 Edwards studied Locke, Berkeley, Leibniz, Kant and Hegel, but found them wanting. He complained they were of limited use to his burgeoning aesthetic interests, ‘pursuing’ — as he derisively put it — ‘metaphysical will-o’-the-wisps’.Footnote 28 Plato seems to have been largely disregarded for the same reason.

Edwards would later argue that the subjective emphasis of contemporary aesthetics derived from psychology and Lippsian empathy theory (Einfühlung) had given rise to a ‘tendency to judge things by diving into the mentality of the spectator’, whereas ‘in a work of art the intellect resides in the thing, and this intellect speaks direct to the intellect which is in us’.Footnote 29 Concentration on ‘the thing which was thought rather than upon the manner of thinking it’ would serve as a corrective to the prevailing psychological and metaphysical bases of contemporary aesthetic theory and idealist architectural thought.Footnote 30

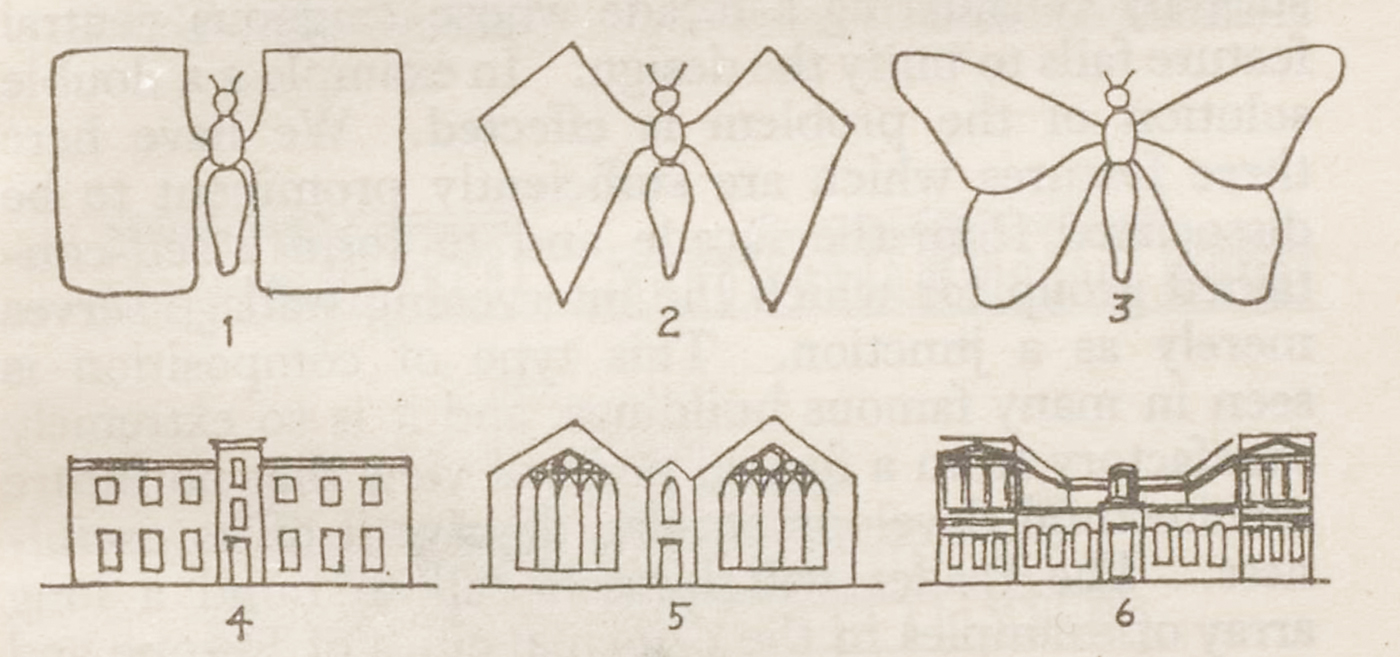

Form, then, was an objective description of things in the world. Predetermined, forms were subject to basic canonical grammatical precepts that Edwards named as ‘number, punctuation, and inflection’, and these universal (even divinely ordained) principles governed design from the anatomical form of a butterfly or human hand up to an individual building and street, and up again to the scale of a city plan and townscape. Civic design in formal terms, therefore, was subject to these questionably pseudo-scientific laws derived from Edwards's eccentric and amateur study of what he described as the aesthetics of botany and zoology.Footnote 31 Number operated according to unity, duality and plurality. Duality required resolution; an unresolved duality, a cardinal compositional sin (via crude Trinitarian theology), was ‘any association consisting of only two things’ that ‘seems to invite the act of severance’.Footnote 32 The illustration shown in Figure 3, from Edwards's 1944 book Style and Composition in Architecture, explains the principle of unresolved duality by comparing butterfly wings with buildings: ‘the devil of unresolved duality, crops up again and again in design and in the most unexpected places’. Figures 1, 2, 4 and 5 in his illustration show ‘freakish’ unresolved duality, whereas 3 and 6 show ‘how the duality of the wings has been completely and elegantly resolved’ through punctuation and inflection.Footnote 33 Punctuation was emphasis at the end or boundary of an object, and inflection was the ability of objects ‘to show their relation to other objects’ through some gesture relating ‘the parts of an object to the whole’ and ‘that whole to what lies outside it’.Footnote 34

Fig. 3. From Arthur Trystan Edwards, Style and Composition in Architecture: An Exposition of the Canons of Number, Punctuation and Inflection (London, 1944), p. 33

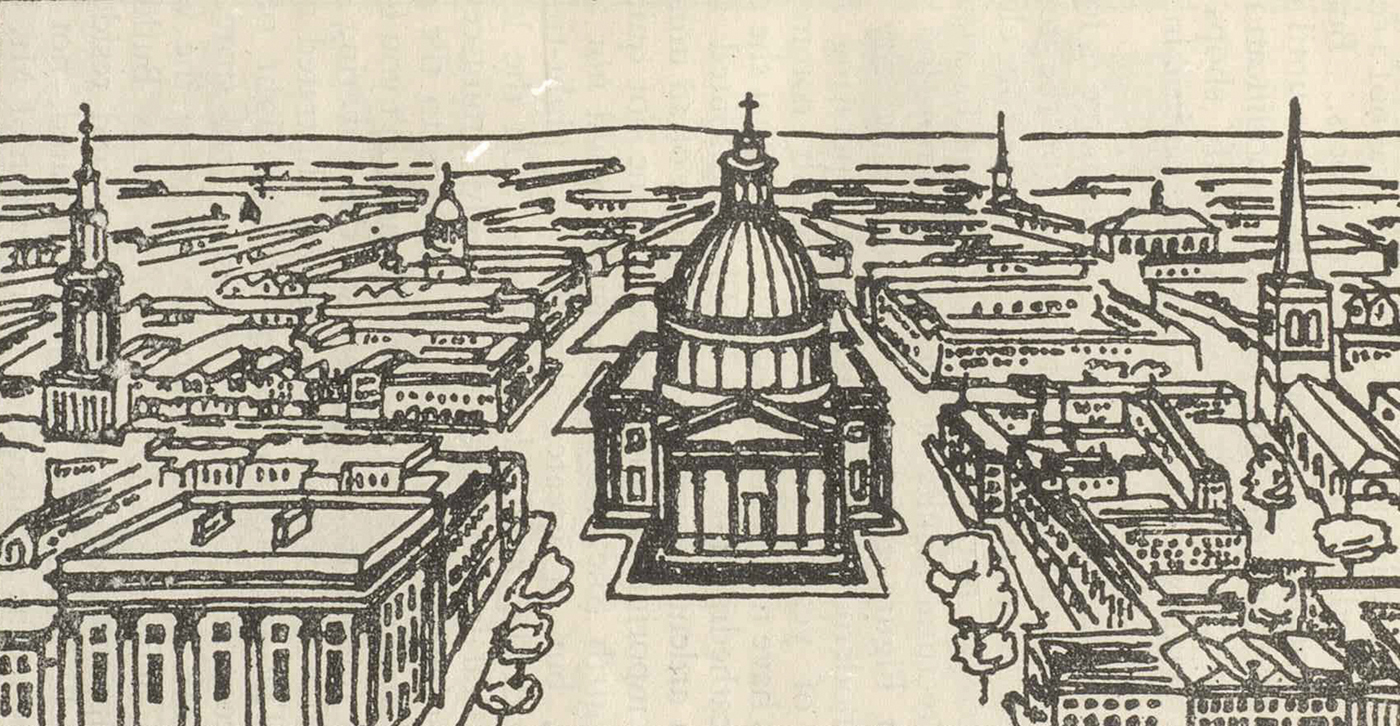

Fig. 4. An expression of ‘good manners’, from Arthur Trystan Edwards, Good and Bad Manners in Architecture, 2nd edn (London, 1945), p. 3

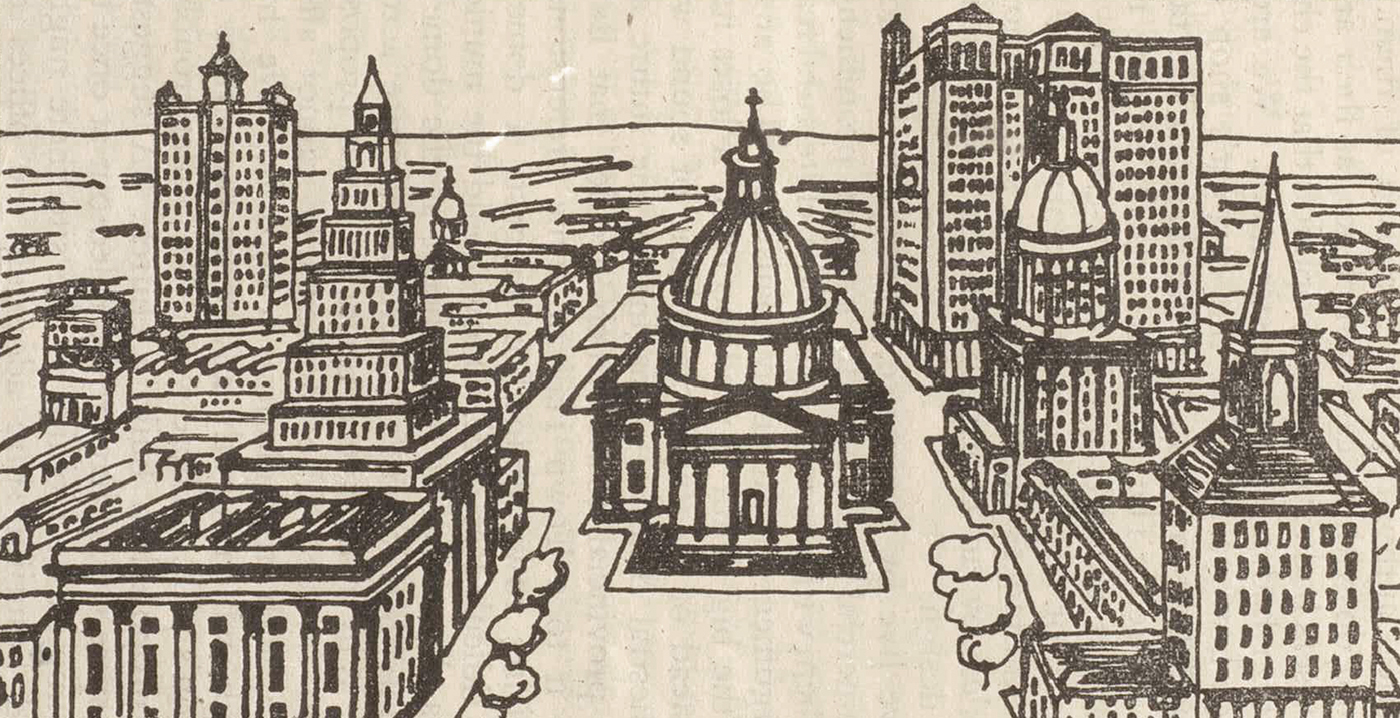

Fig. 5. The same scene with ‘bad manners’, from Arthur Trystan Edwards, Good and Bad Manners in Architecture, 2nd edn (London, 1945), p. 3

Edwards linked these principles explicitly to the design of buildings in Good and Bad Manners in Architecture (first published in 1924), in which he suggested, for instance, that streets were more successful when terminal blocks were emphasised through punctuation and inflection.Footnote 35 Edwards thus showed the importance of formal unity in the cityscape through a ‘centre of interest’.Footnote 36 In Style and Composition in Architecture, he also explained how the grammar of design was applicable to the plans of buildings and cities. These principles were again manifested in the plans and elevations for houses, streets and cities in the second and third prints of the Hundred New Towns for Britain pamphlets published in 1934.

The attempt to articulate rational compositional principles can be seen as a resistance to idealist discourse in design. Rather than defending a particular style as an indication of taste, Edwards sought objective precepts akin to knowledge for the purposes of civic design. Intended to criticise contemporary classical and traditional architecture just as much as Gothic or Modernist, these principles offered a basis for design education, and indeed the phrase ‘unresolved duality’ was still occasionally heard on planning courses in the post-war period.Footnote 37 The ability to apply the grammar of design at different scales demonstrated how the role of the architect-planner could bring consistency of approach to design problems in various scenarios.

For Edwards, the ‘subject’ of architecture and civic design was its use or function, subdivided into the ‘immediate’ (utilitarian purpose) and the ‘general’ (wider social purpose).Footnote 38 He proposed an additional corrective lens to ensure this could be properly discerned — the needs of the ‘average man’. He also promoted a new hierarchy of the visual arts, reflecting the social importance of the six fundamental arts to this ‘average man’. The cultivation of human beauty — and a corollary intolerance for human ugliness — was placed first; second came the art of manners, a ‘determination to avoid becoming an offence to others’, which had implications for propriety in the physical as much as the social public realm; third, the art of dress, which Edwards described as ‘essential to the very structure of social life’; fourth, surprisingly far down the list, was architecture; and finally painting and sculpture, provocatively relegated to the status of minor arts in fifth and sixth places.Footnote 39

Deferring to the judgement of the average man on ethical and aesthetic questions was necessary because ‘he is the upholder of society, and because the institutions of society have been created to supply his wants’.Footnote 40 As the political historian James Thompson has shown, ‘the average man’ was part of the nascent language of public opinion in the mid- to late nineteenth century, another stereotype alongside the ‘man in the street’ and the ‘man on the omnibus’.Footnote 41 For Edwards he was an exalted figure, and a more accurate barometer of public feeling than public opinion, which he dismissed as a partisan tool:

The being whom we are discussing, the human unit who embodies within himself the elementary virtues, who is distinguished by the sanity of thought and conduct without which no community could exist, has not expounded his philosophy of life for our edification and he is without an official mouthpiece.Footnote 42

The anxiety to give voice to the average man in architectural discourse should be seen as part of a wider political shift to contain the socially perilous and destabilising effects of demobilisation, democratisation and reconstruction. This was an attempt to define a newly enfranchised public through the construct of ‘average man’ as its basic unit, with ramifications for professionalism and civic design, which it was the job of criticism to elucidate. This appeal to the public — to ‘fan the ardour of the layman’, as J.M. Richards put it — has been explored by Jessica Kelly in relation to the Architectural Review in the 1930s and beyond.Footnote 43 In that context, however, Richards and his colleagues sought to open the layman's eyes to the possibilities of Modernism in architectural design. This rhetorical technique in fact extended beyond Modernist discourse; Edwards and many contemporaries in the architectural press were also attempting to mobilise a construct of ‘the public’ as a new and meaningful constituency to which professional service should be directed, irrespective of questions of style.

Edwards's new order, underpinned by the belief in the importance of the average man, would subject questions of design to public oversight and scrutiny. Practitioners therefore had a moral responsibility to develop adequate gauges of public approval and relevance. The implications of this were worked out further in Good and Bad Manners, in which he argued that the public should have a ‘proprietary feeling with regard to architecture’. The language of good manners, of architectural politeness, should be the language of architectural criticism.Footnote 44

Public engagement with good-mannered architecture pertained, in Edwards's formulation, to the lofty ideal of ‘Truthfulness’, discussed in detail in Good and Bad Manners. In deliberate contrast to Arts and Crafts and Modernist ideals of honest expression of plan in elevation, he advocated that in architecture, as in social life, ‘it is obvious that good manners consist in expressing certain things, but they are also dependent upon the concealment of other things’.Footnote 45 He attacked the ‘fatal doctrine of the priority of the plan’ and suggested that ‘the plan itself on occasion must make concessions to the elevation’.Footnote 46 Indeed, he argued for the ‘virtues of concealment’.Footnote 47 Concealment did not mean deceitfulness, but a self-conscious artfulness to maintain propriety in the public realm. This principle of masking extended to, or found analogy with, social roles and performances whereby the designer and critic could also adopt an impersonal, even disinterested, persona for the benefit of the wider democracy. Edwards later put this proposal into practice with the establishment of the Hundred New Towns Association, his primary campaigning vehicle for civic design, which was launched as an association of unnamed ‘Ex-Servicemen’ and issued pamphlets under the authorship of ‘Ex-Serviceman J47485’ (Edwards's wartime service number), who appealed not to policy-makers, but directly to the public. This principle of civic design practice owed something to his naval experience, during which he had observed that the British bluejacket ‘has the gift of fluent and picturesque speech [but] he is apt to lose his self-confidence as soon as he puts pen to paper’.Footnote 48 He used the anonymity of a service number to communicate not only on behalf of, but crucially as an ex-servicemen, an ‘average man’, to lobby for a shift in housing policy.

Civic design, therefore, was part of Edwards's solution to a set of practical and ethical questions as well as formal ones. Indeed, part of the common purpose of these early writings was to reintegrate aesthetics and morality. He was explicit that ‘the aesthetic ideal includes the moral as the greater includes the less’.Footnote 49 It was a concern common among critics and theoreticians of the period — to correct the ‘ethical fallacy’ of Victorian critical precepts, to borrow Geoffrey Scott's coining in The Architecture of Humanism (1914).Footnote 50 This would be achieved, Edwards understood implicitly from Scott, neither by dissipating the moralising ambitions and effects of architectural design, nor by emptying out the ethical purpose of critical writing. It required instead a new relationship between aesthetics, ethics and perception. The Things Which Are Seen and Good and Bad Manners can be read as responses to, or further meditations on, some of Scott's themes. The Architecture of Humanism was the pre-eminent work of theory in England at this time and the two men's ideas had been forged in a similar intellectual context.Footnote 51

Edwards carried forward the reintegration of morality and architecture in Good and Bad Manners in Architecture by emphasising the social aspect of architecture through conflating the ‘art of manners’ with the ‘art of architecture’ in his new visual hierarchy. The reintegrated architectural morality established in The Things Which Are Seen would determine in essence the ‘right’ layout of the city and the mannerly principles by which buildings and citizens would relate to one another in it.

MANNERS, URBANITY AND ‘THE GEORGIAN’

Good and Bad Manners in Architecture is known primarily as a passionate defence of the maturity and gentility of John Nash's Regent Street, which, by the mid-1920s, had been all but rebuilt with steel frames and Portland Stone façades. This controversial project, initiated by the Crown Commissioners’ redevelopment of the Quadrant block curving north from Piccadilly Circus (seen on the wall behind Edwards in the cartoon shown in Figure 2), rumbled on acrimoniously over the course of the first quarter of the twentieth century.Footnote 52 In fact, Edwards's chapter on Regent Street, the book's ‘historic example’, is bracketed by arguments derived from Nash and his contemporaries, but more broadly applied to the importance of manners and urbanity in the design of housing, streets and towns.

The book, and the phrase, ‘Good and Bad Manners’, remain Edwards's best-known contribution to twentieth-century architectural discourse. The text was in part drawn from a series of articles that had appeared primarily in Architecture, as well as the Town Planning Review, the Sphere, the Nation, the Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Architects’ Journal.Footnote 53 Edwards later boasted that at least ‘a dozen architecture writers and popular lecturers upon architecture’ had adopted ‘good manners’ as ‘their principal canon of architectural criticism’.Footnote 54 He went so far as to claim that ‘the phrase may even be heard on the lips of Cabinet Ministers and of speakers engaged to give discourses by the British Broadcasting Corporation’.Footnote 55 The book has been described as ‘whimsical’ in the way that it used the concept of urbanity to describe the relation of buildings to one another.Footnote 56 In fact, as the analysis above has shown, the ambition of ‘good manners’ in architecture had a serious moral purpose too, particularly its social aspect.Footnote 57

Edwards argued that the most important architectural unit was the city, and cities should be conceived as buildings standing in relation to each other. Towns and cities that displayed urbanity had ‘good manners, and the lack of it bad manners’.Footnote 58 The latter condition, felt to be prevalent in contemporary urban centres, is shown in Figure 4. Buildings could be said to be well mannered by conforming to a hierarchy, demonstrated in Figure 5: ‘Civic order, social stability, and a fine, conservative temper, are expressed by such an arrangement.’Footnote 59

If The Things Which Are Seen offers an insight into Edwards's conception of design and the designer, Good and Bad Manners helps us to arrive at a deeper understanding of what he understood the ‘civic’ in civic design to mean. The modern and urbane civic aspiration was framed by an imaginary that elided the distinction between the Georgian and the Neo-Georgian, or between preservation and development.Footnote 60 The civic also elided, or subsumed, the public, commercial and domestic realms by creating a higher ideal to which well-mannered buildings deferred in the urban hierarchy. The relationship between the civic and the domestic and commercial, as expressed in Good and Bad Manners and in Edwards's own speculative city designs, can be read not only as a façadist or contextualist argument for the integrity of the streetscape, but also as integrating a critique of the overly functional zoning approach of the Modernist and Garden Cities. Edwards's ideal compact towns still had strongly thematised zones — a central civic centre, a covered ‘bazaar’ for retail and public assembly, residential areas and so on — but these intermixed the civic and the commercial with the domestic, too.

Edwards and Good and Bad Manners have been incorporated into the narrative of burgeoning Georgian preservationism. Douglas Goldring, for instance, suggested that ‘Without it there would probably have been no Georgian Group.’Footnote 61 However, the book was neither a preservationist text nor a defence of historicism, let alone a rigorous historical exposition of Regency architecture. Certainly, it represented a strand of Edwards's writings that showed a sustained interest in Georgian architecture. In a promisingly precocious series of articles called ‘Modern Architects’ (begun in the Architects’ and Builders’ Journal in 1914, but interrupted by the war), he wrote not only about British architects he admired, namely John Soane, Robert Smirke and Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, but also German and French Greek Revival and Beaux-Arts architects of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries such as Leo von Klenze, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste and Léon Ginain.Footnote 62 These were all, as he explained in an introductory essay, exponents of modern principles of classical architecture: ‘In fact, it is the Classic style rather than any special person or group of persons that is the real subject of the present discussion.’Footnote 63 The series was not, therefore, conceived as an ‘appeal to history or to tradition’, but intended to shine a light on then neglected architects who had ‘pondered deeply’ upon classical form and who continued to be sources for contemporary practice.Footnote 64 Further studies in the late 1920s on mid-Georgian work by William Chambers and John Wood the Younger at Bath were deliberately cast in terms of Edwards's own civic design principles — the latter's work was described as inspiring ‘what is fast becoming the “English movement”’.Footnote 65

Edwards's writings on Georgian and Regency architecture added a different dimension to the growing corpus of texts on Georgian architecture in the early twentieth century.Footnote 66 First, they had a European dimension as well as a British one, linking the British Neo-Georgian with Continental developments. They also extrapolated principles of classical design through analysis and interpretation as much as through example. In contrast, books by Richardson, F.R. Yerbury, Stanley Ramsey and others, focused on typology or detail rather than the elucidation of principle or aesthetic theory.Footnote 67 Edwards was more interested in intentional, formal design and a holistic critical apparatus than in the happened-upon detail of vernacular construction, expressed for instance in A.E. Street's mournful and relatively indiscriminate defence of the ‘old-world’ charm of Queen Anne's Gate or Great Ormond Street earlier in the century.Footnote 68 In other words, Georgian precedent was not good for or worthy of revival in itself, but required discernment and discrimination to uncover its underlying design procedures.

Furthermore, Edwards linked the conception of manners and urbanity back to the Georgian — and increasingly Regency — civic tradition, not the parochial vernacular that had grown out of the Arts and Crafts movement and Queen Anne revival, and was increasingly used by housing architects such as C.H. James and Louis de Soissons. In this regard, Good and Bad Manners was not just another lament for Regent Street. It was a reclamation of the ‘essential modernity’ of the Regency and late Georgian period, as he described it elsewhere, distinct even from many of the Neo-Georgian cottage estates and tenements then being built, for instance, by public authorities such as London County Council and through private enterprise at Welwyn Garden City.Footnote 69 The word ‘cottage’, commonly used to refer to small-scale dwellings in the period, appears infrequently in Edwards's writing on housing, perhaps because it undermined the civic ambition expressed by urbanity.

Although recent analyses of the post-war period have noticed the use of the term ‘urbanity’ among modernist architects, they have failed to acknowledge prominent, but architecturally conservative, voices of the interwar years.Footnote 70 In fact, urbanity and civic design were sometimes mobilised against Modernist practice at this time. Furthermore, designers at the centre of post-war networks of influence — namely Thomas Sharp and Gordon Cullen — had used Edwards's books as ‘primers’ for the development of their own townscape principles.Footnote 71 They in turn influenced designers such as Frederick Gibberd, who deployed ‘urbanity’ to reinstate a visual or aesthetic ‘town-like quality’ to the overly social and functional aspects of architecture and planning from the 1930s, especially residential development.Footnote 72

For Edwards, by contrast, urbanity subsumed the domestic within the civic. These ‘two chief qualities proper to a house’ — the domestic and the civic — led to an interpretation of the picturesque that contrasted with that adopted by Christopher Hussey or Nikolaus Pevsner:

Many of the most formal compositions are even more picturesque, in the true sense of this word, than are the haphazard arrangements of buildings one often sees in medieval towns, for they comprise pictures which are nobler, of a higher unity, and more significant.Footnote 73

The civic and the domestic in harmony evoked the architecture of the eighteenth century and stood in marked contrast to the late nineteenth-century domestic ideal of the Garden City. Good and Bad Manners was an attack on some of its bastardised suburban motifs. The charge of monotony, for instance, commonly levelled by detractors against Georgian and Regency street design such as Regent Street, was turned around to criticise its opposite, the ‘Vice of Prettiness’ prevalent in the repetitive ruralism of the ubiquitous Tudoresque gable in contemporary suburban domestic architecture.Footnote 74 The defence of an alternative tradition, in which housing was laid out in accordance with principles of civic design, increasingly became Edwards's abiding concern.

TOWARDS A HUNDRED NEW TOWNS FOR BRITAIN

The problem Edwards faced in the early 1930s was how to propagate these views. In a series of letters to Sharp in 1933, he floated the idea of collecting ‘together a group of architects and others who are prepared to make a fight on behalf of a sensible ideal of civic design’.Footnote 75 Despite a small but growing anti-Garden City contingent in the 1920s and early 1930s, encouraged by the success of Sharp's Town and Countryside (1932), Edwards felt that Unwin's grip was strangling their efforts.Footnote 76 Adshead and Abercrombie were both ‘at heart opposed to the Garden City’, he wrote, but were ‘far too anxious to secure the loaves and fishes [in the form of housing schemes commissioned under the 1919 Act] to declare their opinion openly’.Footnote 77 In a later letter he poked fun at Abercrombie's Town and Country Planning (1933) as ‘wonderful value for half a crown’, but

on the critical side he is weak. He is much too kind to Le Corbusier, for instance, while having himself executed so ma[n]y garden suburb schemes under the 1919 Housing Act, one could scarcely expect him to be too severe upon ‘open development’ a la Unwin. Obviously he could not bite the hand that feeds him or has fed him so liberally.Footnote 78

Clough Williams-Ellis was dismissed as an ‘opportunist’, as was Reilly, too afraid ‘to champion a cause wh[ich] might set him at variance with important people in the profession’.Footnote 79

The outburst of candour and bitterness — paranoia even — in these exchanges suggests how Edwards saw himself in the early 1930s. He clearly felt himself an intellectual outsider, jealous of others’ successes, and frustrated that his increasingly developed principles of civic design were not becoming more deeply entrenched among his contemporaries. What many of his targets had in common, though, was that they were the profession's natural charmers and communicators. Furthermore, the ideals of the Garden City had become enshrined in legislation and achieved a widespread consensus. As housing and slum clearance rose up the political agenda in the early to mid-1930s, however, Edwards spotted an opportunity to propagate of his civic design principles and to challenge establishment thinking. Initiated in late 1933, the Hundred New Towns campaign brought together the civic design group he had mentioned earlier that year to Sharp. Rather than enlist the help of Sharp, Reilly, Abercrombie and others, however, Edwards attempted to build a grassroots campaign group that privileged lay expertise among the general public and specialists in other fields. This campaign provided Edwards with a vehicle to drive forward his civic design ideals: the distinction between subject and form; the need for the ‘artist’ (designer and critic) to operate impersonally for the benefit of the community; the principles of good manners and urbanity; and the intermixing of the civic and the domestic.

Edwards's ideas, as we have seen, reflected the practice of his teachers and colleagues at the Liverpool School, who were ‘unashamed urbanists and classicists, dismissive of the provincial pretentions as well as the picturesque neo-vernacular of so many garden suburbs’.Footnote 80 Adshead, Ramsey and Abercrombie's model ‘industrial village’ for the construction company Dorman Long, Dormanstown, where they employed the ‘Dorlonco’ system of steel-frame construction pioneered by the firm, is now a well-known example of their counteraction.Footnote 81 This idiom of formalised housing and street plans stood in contrast to other pre-war schemes at Hampstead, Bourneville and Port Sunlight.

Under this influence, Edwards had been an early and persistent critic of the Garden City-inspired orthodoxy of housing development in the first half of the twentieth century and of the powerful Idealist and Socialist ‘Ruskinian tradition’ in architectural thought carried forward by Unwin and his circle.Footnote 82 His first published articles, which appeared in the Town Planning Review in 1913, were criticisms of the Garden City movement and outlined principles he would continue to refine after the war.Footnote 83 He advanced the argument that workers ‘quite unconsciously show their disapproval of the well-meant schemes of those who would reform them. If upon the edge of an industrial district a speculative builder erects workmen's cottages, it frequently occurs that they will go untenanted.’Footnote 84 By contrast, dilapidated terraced houses in city centres were in relatively high demand. The solution was to improve the provision of housing at high density, and to avoid the confusion between ventilation and overcrowding. The Garden Suburb was singled out for particular censure: ‘It gives us the advantages neither of solitude nor of society.’Footnote 85

Edwards agreed with Ebenezer Howard (founder of the Garden City movement), Unwin and their followers on the pressing need for a policy of decentralisation and for a major national programme of building and improvement for the poor, but he proposed their realisation by different means. He was adamant that Howard's formulation — that the solution to the damage done to town and country was to create a hermaphroditic town-country — was mistaken. His own policy of decentralisation was to relieve congestion in overcrowded cities, not to abandon urban centres. ‘Our towns’, he wrote in 1913, ‘should be so beautiful that everybody would wish to stay inside them. If they are unhealthy we must make them healthy. If they are noisy we must take steps to make them less so. If they are too smoky, we must abolish smoke.’Footnote 86 He advocated the creation of new urban centres with high densities, or controlled crowding to generate urbanity capable of forging civic bonds.

Edwards continued to write on the subject of housing in the late 1910s and 1920s. In 1919, somewhat surprisingly given his role at the ministry, he wrote a candid editorial on ‘Housing Principle and Practice’ in the Architects’ and Builders’ Journal.Footnote 87 Boldly departing from official policy, he criticised schemes of building predicated solely on little groups of self-contained dwellings — the sort of low-density cottage design in open development for which his team was responsible. This showed an independence of mind at odds with a growing consensus in Whitehall.

That consensus was most clearly expressed in the Tudor Walters report on housing. Its champions, architects in the Ministries of Munitions and Reconstruction, christened the ‘Tudor Walters Group’ by Mark Swenarton had gained control of the new Ministry of Health's enlarged Housing Department charged with delivering the post-war housing campaign, ‘Homes Fit For Heroes’Footnote 88. Their influence over government policy had begun in the early 1900s, and by 1914 the ‘garden city lobby’ (in part through Unwin) ‘was well established as adviser to the Cabinet on housing questions’.Footnote 89 Edwards must have stuck out among this group. He later expressed regret at his inability to ‘exert some influence in determining the character of the housing schemes financed by the State’.Footnote 90 Although he worked on Unwin's personal staff for six years, he was ‘powerless to do anything and was in fact principally employed in devising schemes for checking contractors’ accounts’.Footnote 91

Dissatisfaction at the ministry and with the methods of the housing division perhaps helps to explain Edwards's use of a voluntary association as a vehicle for housing reform, free from covert politicking and internal lobbying. He bitterly recalled, for instance, that when ministry officials expressed doubt about the twelve dwellings per acre limit, ‘Unwin whipped up his parliamentary henchmen to make a protest against the suggested abandonment of the humane standards of life which after years of propaganda housing reformers had succeeded in establishing’.Footnote 92

Edwards's ideas about housing design were developed not solely in opposition to the state schemes. He was capable of measured innovation in planning and detailing, which became a consistent theme of his journalistic output in the 1920s. Some of the ideas that featured in his series on ‘The Twentieth Century House’, which appeared in the Architect and Building News in 1927, were carried forward in later projects and the Hundred New Towns campaign.Footnote 93 For instance, he fleshed out in detail questions of lighting, sanitation and ventilation for houses with greater standards of hygiene, which he called ‘The Aesthetics of Sanitation’ and ‘The Aesthetics of Hygiene’. The accompanying speculative designs incorporated ideas such as a ‘recess’ to contain pipes and concealing other services by the ‘slight projection of wall at the opening of the recess’.Footnote 94 He also returned to earlier work on sunlight and ventilation (published in the Town Planning Review in 1920–21), in which he attempted to demonstrate the lack of a sound evidence base for planning regulation.Footnote 95 The suggested distance of 70 ft between the fronts of houses facing each other on a street and across the gardens lying back to back — intended to ensure sunlight in all rooms — was a particular bugbear, and he devised a table of graphs (Fig. 6) showing hours of sunshine according to width and orientation of street at different times of the year.

Fig. 6. ‘Hours of Sunlight in Broad and in Narrow Streets’, reproduced in Arthur Trystan Edwards, ‘Sunlight in Streets’, Town Planning Review, 8.2 (April 1920), pp. 93–98 (Liverpool University Press)

Edwards also developed speculative plans for small houses which departed from Tudor Walters conventions. In one, the front of the house was placed almost on the road — the outer wall being separated from the pavement solely by the depth of a 4 ft porch. A broad frontage of 38 ft allowed for a shorter garden without compromising too much on overall surface area. An additional door on the street front for coal, goods and tradesmen obviated the need for alleyways, and sanitary services could also be placed on the street front, tidied up through the use of recesses. Such designs, along with further proposals for larger or semi-detached houses, formed a personal pattern book from which Edwards would draw in his propaganda campaigns.

Another of his speculative designs for working-class housing was a street that provided for ‘The Exclusion of Dust and Noise’ generated by increased motorcar ownership. The standard solution to this problem had been to situate houses further away from main roads, but this step could cause problems with sewage and untidy front gardens. For Edwards, the ‘obvious solution’ was ‘to place the houses right on the pavement to act as a screen between the gardens and the public thoroughfare’, and then place the main living rooms towards the garden.Footnote 96 The diagrams show the suggestion of a blind wall facing the street inspired by Soane's perimeter wall for the Bank of England (or even George Dance's Newgate Prison), punctuated with blind windows and column screens, and recesses for two entrance doors as in the other small house plans. This concept evolved into the ‘Silent House’, exhibited at the Building Exhibition at Olympia in 1930, designed by Edwards and organised with H.G. Montgomery. Here, Edwards created a suite of rooms formed of sound-resistant materials and provided opportunities for the public to test their effects.Footnote 97 The ‘Hush-Hush House’, shown at the Ideal Home exhibition the following year, took the idea further. With a decorative door and no windows on the front or side walls (though with ‘ample scope […] for artistic treatment of the brickwork’), and featuring a roof garden and pergola, the house was enveloped with a ‘sound-proof blanket of special material and lined with a wallboard [Treetext] which is a sound and heat insulator’.Footnote 98

The ‘Silent House’ and the ‘Hush-Hush House’ showed not only Edwards's growing interest in publicity and action, but also his ability to prototype ideas and his belief in the applicability of his solutions to real-life problems. The Hundred New Towns campaign formed in 1933 (and later formalised as the Hundred New Towns Association) was the climax of his efforts in housing. It was his most significant practical contribution to the discourse of civic design in the interwar period and beyond.

Though none of Edwards's projected new towns or high-density streets were built, the manner and discursive contributions of the Hundred New Towns campaign's propaganda activities should be seen as part of a wider trend in voluntary and associational culture in the 1930s housing debate. In March 1933, the Ministry of Health's departmental committee on housing issued a report on the role of local authorities in slum clearance. Known as the Moyne report, it also explored whether the voluntary sector could be recognised as a potential major provider of housing if formalised through a national organisation. As Patricia Garside has described, the report glorified the public utility societies and questioned the legitimacy of the emerging Ministry of Health-local authority nexus.Footnote 99 In response, local authorities sprang into action, asserting their own role as house builders, curtailing the voluntary sector's efforts. Elizabeth Darling has argued, however, that because of ‘the continued adaptability of the sector’, voluntary housing associations developed a ‘primarily advisory, rather than provisory, role’ in order to ‘assume a position of influence in wartime reconstruction debates’; Edwards's activities should, therefore, be seen in this context.Footnote 100

The call for a hundred new towns was by no means new in the 1930s. In 1918 a group of self-styled New Townsmen, including Charles Purdom and Frederic Osborn, had published New Towns After the War: An Argument for Garden Cities, in which they argued that, to make up the housing shortfall, the nation should ‘Build a Hundred Garden Cities!’ over five years, providing one million houses with government funding.Footnote 101 Edwards clearly sought to reclaim some of the Garden City faction's rhetoric, aware that to steer policy away from low-density open development would require careful manoeuvring. He launched the campaign with a pamphlet in October 1933, followed by a second printing in February 1934 and a third in November that year.Footnote 102 The Hundred New Towns Association followed shortly thereafter. According to its literature, the nascent organisation comprised a ‘Fraternity of Ex-Soldiers and Sailors’, but it is unclear how many were involved, where they met, or how frequently — if indeed it was ever a formal organisation.

The premise was that industry and the industrial population needed to be more effectively distributed around the country (emancipated by the completion of the national grid that year). Decentralisation would not serve to eradicate urban centres and urban life; rather, it would make them more sustainable in the long term. Once the new towns had been created, for instance, existing cramped accommodation would be reconditioned and smaller cottages combined to form larger dwellings. This was in line with housing policy, in which wide-scale ‘reconditioning’ was increasingly seen as part of a package of reforms.Footnote 103 The new towns would be distributed across the United Kingdom — with seventy-six in England, fifteen in Scotland and nine in Wales (Fig. 7). A higher proportion would be located in the seven northern counties to mitigate southerly migration; no new towns would be built within a 25-mile radius of Charing Cross; and several southern new towns were proposed in coastal locations. The plans of the new towns would have ‘Compactness’ (in other words, high density), ‘Order’ (zoning) and ‘Flexibility’ (mixed-use development and adaptability to different topographies and circumstances).Footnote 104 Edwards dismissed once again the limit of twelve dwellings per acre on open development and demonstrated that high-density terraces, even of a similar density to some slum areas, could be made amenable.

Fig. 7. Back page of the second printing of A Hundred New Towns for Britain, 1934

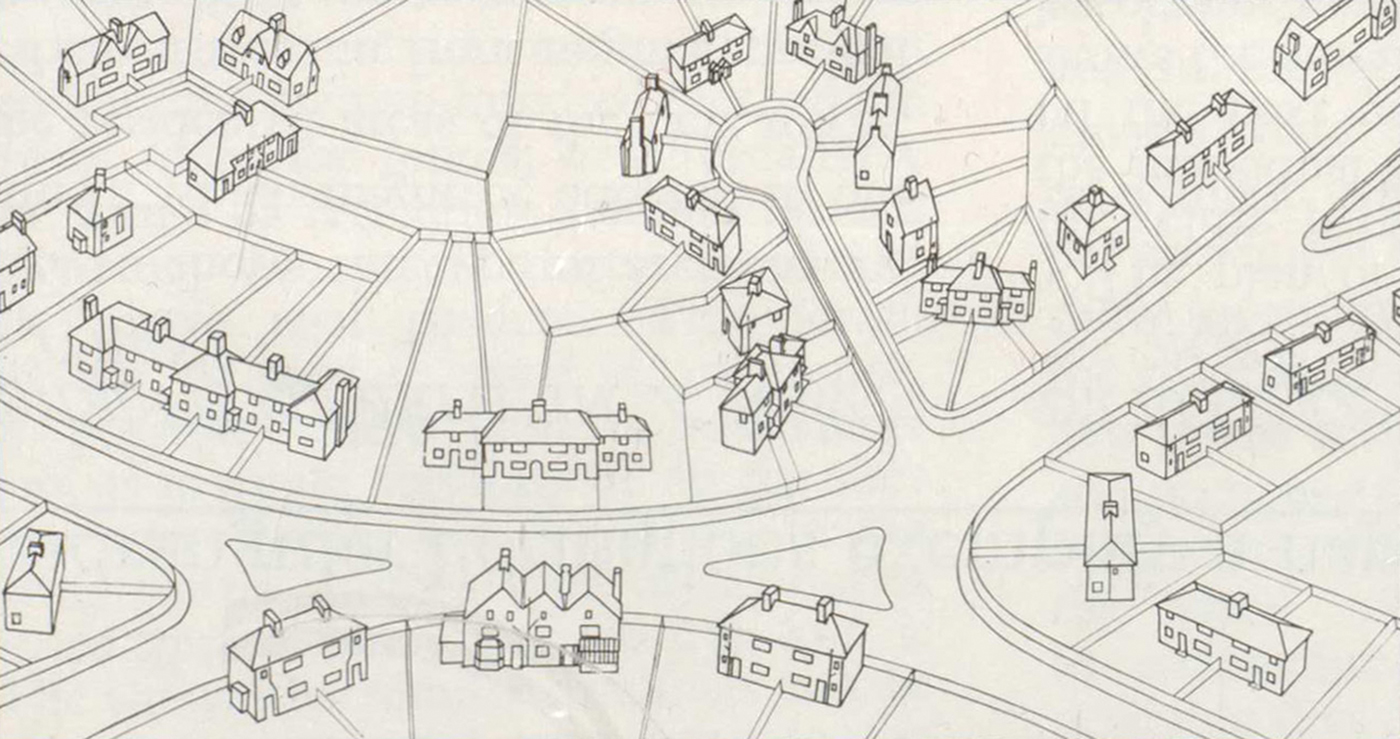

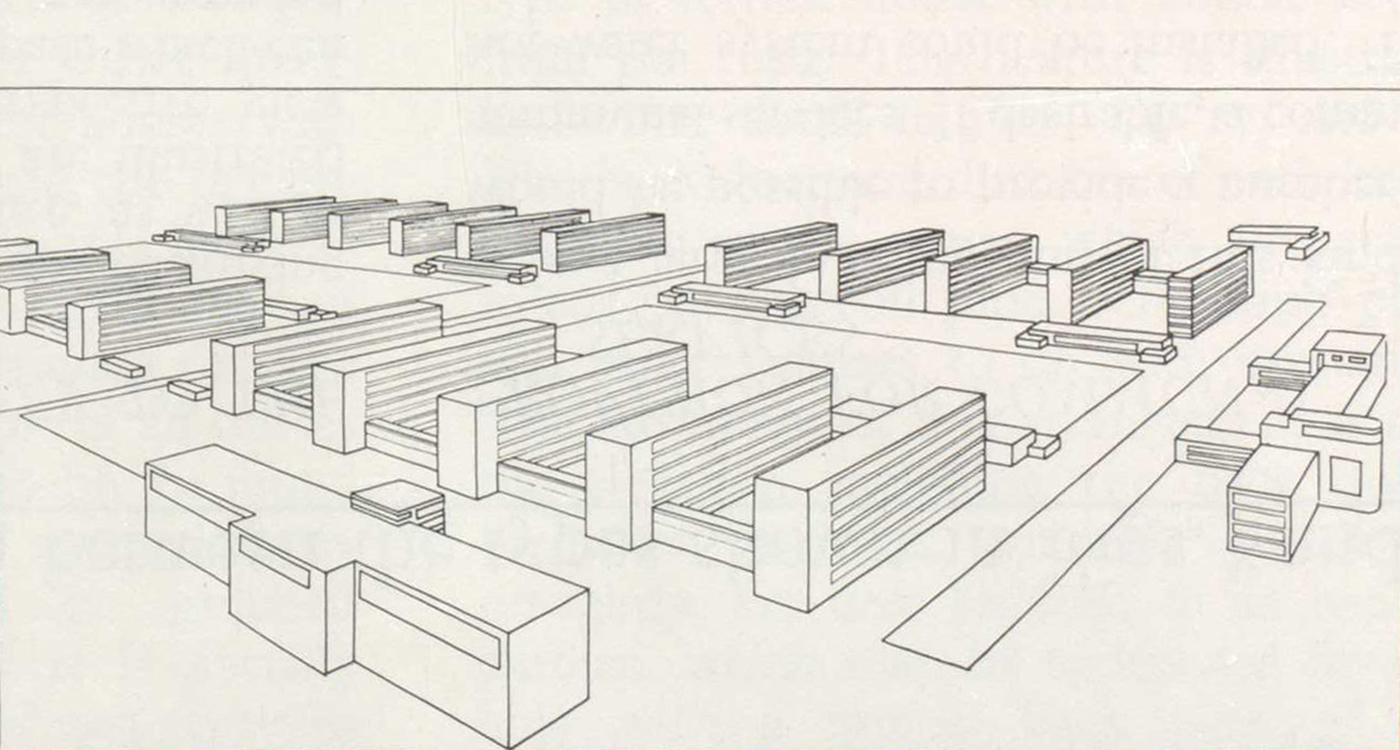

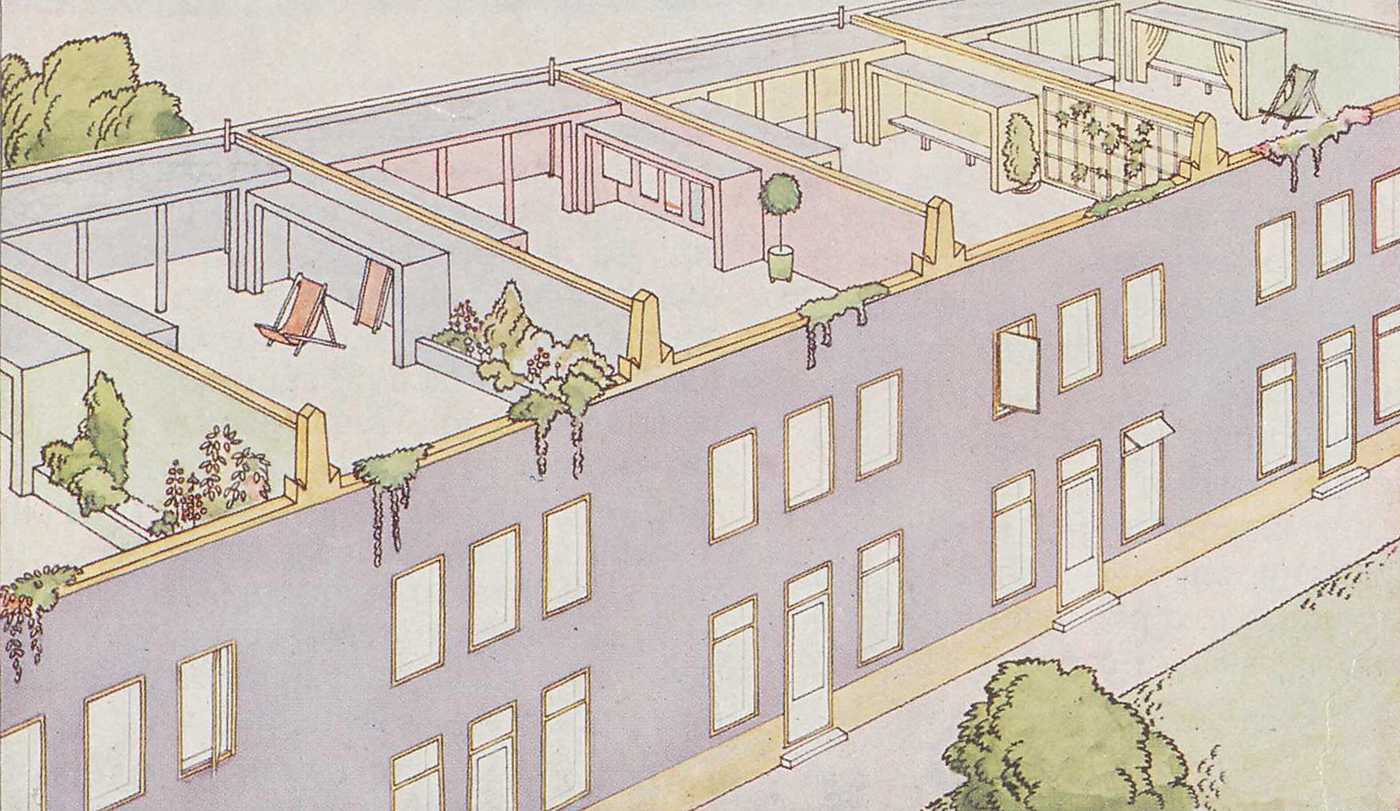

Edwards's proposals showed ideal new towns arranged on circular plans (Fig. 8), with predominantly sector-based zoning; concentric links and repeating features would provide easily accessible amenities, alleviating the need for Garden City satellites connecting to a parent city. Green wedges would substitute green belts, particularly once major metropolises had been significantly decentralised. Individual units would combine into formal terraces set around squares of 20 to 30 houses per acre at a lower end, and — a clear nod to Georgian and Regency precedent — with the possibility of brick facings or painted stucco on concrete or steel frames (Fig. 9). Just as the open development of ‘villadom’ was unacceptable, so too were tenement blocks and high-rise buildings (Figs 10 and 11), which Edwards viewed as antisocial, particularly for families. At the front of his typical houses, facing open public space, glazed doors on the ground floor offered convenient access to a shared quadrangle, and sun terraces on the roofs of taller units reflected an early twentieth-century devotion to health and hygiene through light and fresh air (Fig. 12). The rear elevations, facing the street, were designed to be neat and tidy, with recesses for back-door entrances, waste and storage, and a low screen wall to keep ‘passers-by a little distance away from the kitchen windows’.Footnote 105

Fig. 8. From Arthur Trystan Edwards, ‘A “Model” Town Designed for Traffic’, Town Planning Review, 14.1 (May 1930), pp. 34–41 (p. 35). This plan was reproduced as the ‘archetype’ town plan for the Hundred New Towns for Britain campaign (Liverpool University Press)

Fig. 9. ‘Street Frontage of Terrace Houses exemplifying proposed new Hygienic Standard’, from A Hundred New Towns for Britain (3rd edn), p. 56

Fig. 10. ‘Villadom in “Open Development”’, from A Hundred New Towns for Britain (3rd edn), p. 47. The caption for this image and Figure 11 reads ‘Neither of the types of Urban Development […] should be encouraged’

Fig. 11. ‘Repetitive Blocks of Tenements’, from A Hundred New Towns for Britain (3rd edn), p. 47

Fig. 12. ‘As many as possible of the new Dwellings should be provided with Roof Gardens’, from A Hundred New Towns for Britain (3rd edn), p. 52

Here was the summation of Edwards's civic design principles for individual housing units, streets, terraces and cities on a national scale. It amounted, in his words, to a ‘Scheme of National Reconstruction’, echoing the earlier post-war concerns of The Things Which Are Seen.Footnote 106 The campaign's proposals embodied his principles of formal composition, but also allowed him to enact the applied ethical responsibilities of the critic and designer. The Hundred New Towns Association was perhaps the only architect-led voluntary housing association lobbying for sophisticated civic design principles in the interwar years, and was certainly the most influential. It was, furthermore, the only one of these bodies to have proposals for the integrated development of new cities and towns on a national scale.

The intensity with which Edwards pursued this project in the 1930s and 1940s must form the subject of a more focused account, but it is essential to understand that the Hundred New Towns was not an unworkable, incoherent or unthinkingly reactive programme to solve the housing problems of the interwar years. It was the opposite — a deliberate and sustained propaganda campaign, based on fastidiously worked out and ardently held principles of civic design intended to steer policy.

CONCLUSION

Reflecting on his classical studies as an undergraduate, Edwards described Plato as a ‘hostile witness’ against his own age, rather than its ‘true interpreter’.Footnote 107 It is tempting to see Edwards in the same vein. He was part of the prevailing architectural culture and practice, indeed at the heart of the establishment, with the accoutrements of class and education. But he was also one of its most vociferous critics, often taking positions counter to what he might be expected to think and say. As interwar history, especially architectural history, continues to develop in new and bold directions, figures such as Edwards can help historians to rethink some ossifying certainties and tropes.

His critical procedures and precepts were eccentric, but not whimsical. They derived from conviction and an established ‘world view’ that guided his opinions from small details — preferences or dislikes for minor formal elements of architecture such as shallow domes or ogival arches — to questions of urgent national and political importance, such as the distribution of industry and housing for the working class.

Writers on interwar architectural history tend to deal with aesthetic theory, architectural discourse and planning debates discretely, yet contemporaries understood the complex ways in which they were connected. Edwards's civic design was a unifying concept that could link the still-nascent practice of planning to the ever-precarious profession of architecture, and even bolster it. The role of the architect-planner emerged in the interwar period, albeit in a different context from the technocratic apparatus that grew up in the welfare state. Edwards's theory, criticism and campaigning provide one example of how contemporaries envisaged it. Operating under the strictures of by-law regulation and the negotiation of private landowners’ interests, it articulated the needs of the new and expanded ‘public’. Situated in aesthetic debates, Edwards developed his basic precepts of ‘subject’ and ‘form’ — the social aspect and outward appearance of buildings and their interrelationships — to inform ‘good manners’ and ‘urbanity’, building on the living tradition of Georgian architecture. If ‘design’ was the object of ‘form’, ‘civic’ was the subject, and Edwards wrestled with the implications of this dichotomy in a world changing rapidly, both physically and socially.

The important question of influence is difficult to measure. Compared with his two near-contemporaries, Robert Byron and Geoffrey Scott (the great critic and theorist of their generation respectively), Edwards was perhaps less flamboyant and lived too long to be lionised in the same way. He was, however, highly visible in the specialist press. From the early 1930s, his journalistic output seems to have reduced slightly, though he appeared fairly regularly in the early issues of the new title Architectural Design and Construction (later Architectural Design), writing a series of ‘further reflections’ on Good and Bad Manners and Modernism in the middle months of 1933.Footnote 108 He also wrote sporadically for the Town Planning Review and the Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects throughout his career. In the non-specialist press, aside from occasional pieces in journals and reviews, he had a regular column in Financial News, and from 1947 until the 1960s wrote the ‘Architecture To-Day’ column for the Financial Times.Footnote 109

The list is by no means exhaustive — book reviews, unsigned editorials and one-off articles are peppered throughout the interwar press. Together these writings chart his professional allegiances and friendships, but they also tell us something about his perceived audiences and preferences. What is clear is that Edwards had a significant reach in promoting principles of civic design, which guided his critical appraisals. In this regard, he also makes a valuable case study of the jobbing journalist, particularly in the 1920s. While that has not been this article's focus, such a ‘bottom-up’ study might helpfully complement detailed work on ‘top-down’ editorial policy and Modernist strategy in constructing readership in the history of British architectural journalism.Footnote 110

Edwards's impact on and participation in the post-war period is patchy, but undeniable. Sharp's Town and Countryside owed much to Edwards, not least its espousal of manners and urbanity. John Pendlebury has suggested that Sharp ‘primarily knew of Trystan Edwards through Good and Bad Manners in Architecture’, and not his much earlier anti-Garden City polemic, but this is a misreading of the correspondence between Edwards and Sharp in 1933 and a typical underestimation of Edwards's influence. Sharp in fact held Edwards's ‘books and general writings on architecture and town planning in such high esteem’, and knew about the invectives he wrote against the Garden City in the pre-war period.Footnote 111 Samantha Hardingham has shown that Edwards influenced Cedric Price's ‘methodology of presenting unsolicited schemes to broaden debate, as well as his use of diagrams to describe the essential qualities of a city plan’.Footnote 112 Edwards was also a strong and continual influence on Max Fry, and had a profound effect on Lionel Brett, who recalled in his autobiography that his desire to qualify as an architect ‘had become a social as much as an aesthetic obligation under the influence of a stammering bundle of Welsh idealism called Trystan Edwards, who used to visit Oxford to publicize his bold scheme for a Hundred New Towns’.Footnote 113

Edwards had his finger on the pulse for the half-century leading up to his death in 1973. In the year of the collapse of Ronan Point tower block in east London, he published Towards Tomorrow's Architecture: The Triple Approach (1968), in which he parodied his Modernist nemesis, Le Corbusier, and rehashed many of his arguments and illustrations from the 1920s, perhaps with some sense of vindication.Footnote 114 In this respect, Edwards links critiques of Modernism at its so-called end back to its period of great triumph, and further back still to the pre-war world, in which critiques of Victorian architecture, theory and planning were just beginning to coalesce and enter the mainstream. Through all of this, the concept of civic design was core to defining a new vision for expressing modern life in the built environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am indebted to the anonymous reviewers for invaluable advice in refining the focus of this article. Otto Saumarez Smith has patiently indulged many conversations about Trystan Edwards and provided useful references for his influence on post-war planners. He, Elizabeth Darling and Elizabeth McKellar read earlier drafts of the text, and their comments are much appreciated. I am also grateful for the feedback and discussion that followed the presentation of previous incarnations of this research at various conferences and seminars at the University of Oxford. Finally, thanks are due to Julian Holder for many useful suggestions during editing.