In the British Museum, there is a lovely statue of a female deity which is said to be from Dhar, the centre of our protagonists’ zone of action, but from many centuries before they appeared. The museum’s webpages note that this is a statue of Ambika, a deity shared by Hindus and Jains. The base of the statue bears a Sanskrit inscription which declares that the statue was commissioned and dedicated by a Vararūcī, who was intent on the Candranagarī and Vidyādharī branches of Jaina religion of Bhoja the king, and who had also dedicated a statue of Vagdevī and a triad of Jīnas (Jaina adepts). King Bhoja is a legendary king of the Rajput Parmar dynasty, who ruled from his capital in Mandu in the first half of the eleventh century; the date on the stela is 1091 Saṃvat, which corresponds to 1034 CE.Footnote 1

There are other claims regarding the sectarian identity and historical provenance of this statue; claims which are of a piece with efforts to recreate a glorious Hindu past for India, anchored on to specific personalities and places. Bhoja Raja, and his legendary royal complex, Bhojaśālā, form a regional version of that story of the Hindu nation. According to this account of the story, the statue in the British Museum is not of the amphibious deity Ambika but of the Hindu goddess Sarasvatī, and that it was originally situated within the Bhojaśālā complex which was (predictably) later destroyed and built over by Muslim invaders.Footnote 2 The Mandu story and the historical wrongs it seeks to right are structurally identical with the more notorious efforts in Ayodhya, Mathura and Banaras: in each of these places, there is an intensified sacred geography, standing as symbol of a sectarian identity posing as national. That sacred geography is focussed on specific architectural complexes whose present and tangible reality simply do not match with the idealised past projected on to them. The ephemeral Bhojaśālā’s historical existence is based on extrapolation from certain inscriptions, discovered inside a building which is also known as Kamal Maula’s mosque (Figure 1.1). This building is currently under the surveillance of the Archaeological Survey of India, which sells tickets saying ‘Bhojashala/Kamal Maula mosque’. Pious Muslim men offer prayers outside the building; Muslim women and men throng to the dargāh (tomb) of the thirteenth/fourteenth-century Chisti saint Kamal Maula, or Kamal al-Din MalawiFootnote 3 that stands next to it, and locals of all religions flock to the ʿurs (annual death anniversary celebrations) of Kamal Maula which enclose and enfold this disputed complex. In Mandu, as in all these other places, there are other people and inconvenient histories, which, with the convergence of a range of local and national aspirations in the early twentieth century, began to be seen as intrusions.Footnote 4

There are other ways of reading such material heritage, ways that permit us to view history as accretion, not epiphany.Footnote 5 At the same time, the competing aspirations that jostle to frame such heritage are themselves the stuff of history; stories themselves have histories. For example, a flattened notion of Hindu nationhood is not sufficient to understand riots over a proposed Bollywood film about a fourteenth-century queen; we need works such as Ramya Sreenivasan’s to understand the evolution of the allegorical Sufi story of Queen Padmini and its entanglement with Rajput political aspirations in Mughal and post-Mughal times.Footnote 6 On that note, we have works by Prachi Deshpande,Footnote 7 Samira Sheikh,Footnote 8 Cynthia Talbot,Footnote 9 Chitralekha ZutshiFootnote 10 and Manan Ahmed,Footnote 11 which teach us how to tell stories about stories. All these scholars have explored creative as well as functional narratives about the past with which various South Asian martial groups – Rajputs, Marathas, Dogras, Mameluk Arabs – have repeatedly redefined themselves and their realms from the early modern era until the present day. In each of these cases, these royal stories have been subsequently discovered in the golden age of partnership between Orientalism and nationalism in order to establish the identity of a region.

This south-western corner of Malwa, our protagonists’ hunting grounds, is not associated with a text quite as powerful as Prthvīrāj Rāso or Chāchnāma, but, as we have already seen,Footnote 12 Dhar has its own lost and found hero in Raja Bhoja of the Paramara dynasty. Rulers of the small princely state of Dhar have asserted descent from the Paramara dynasty since the nineteenth century, with the predictable combination of British Orientalism, Indian nationalist scholarship and political patronage. Like Gujarat, Marathwada, Sindh and Kashmir, Dhar and Malwa are located within an area of layered empires; it is just that, despite some significant and ongoing efforts, its story remains more interrupted.

The purpose of this chapter is not to tell the story of a region per se, nor to explore the successive formation of polities. The aim here is to conceptualise a zone – political, social and cultural – within which the protagonists of this book negotiated law. I am guided by the works mentioned, which both interrogate the concept of region and show us new ways of writing regional history. I am also inspired by those works that think of regions in terms of routes – not so much bounded territories, but significant circuits of circulation – of traders, merchandise, soldiers and war.Footnote 13 The protagonists of this story remained ensconced in the same region for at least four hundred years – more, according to family lore – and yet, that same family history was premised on the story of a journey. Settlement and movement are more complementary – as lifestyles but also as political styles – than we usually remember them to be.

In my case, I am interested in space because it is inherently related to law; and while the concept of jurisdiction – that combination of spatiality and authority, of geographical and abstract space – does leap to mind, here I would like to try and move beyond jurisdiction and all that Lauren Benton showed us it could do.Footnote 14 There are at least two reasons why I think that we need a better term than jurisdiction in order to conceptualise the negotiations with power and legitimacy – i.e., law – that the protagonists of this current story engaged in. The first reason is the wordiness of jurisdiction: derived as it is from the Latin pair juris and dictio, it renders a sense of law as words above all, captured best in texts and talking heads. The protagonists of my story expressed themselves in words, too, but their ability to speak derived from a range of activity and authority that I think needs a different word, one more closely linked to South Asian lexis and praxis. This is not an argument in support of the anti-intellectual conceptualisation of pragmatic ‘jurispractice’.Footnote 15 As I have said elsewhere,Footnote 16 looking beyond formal institutions for law in South Asia (and maybe elsewhere, too) need not mean dismissing the possibility of abstract thought. It is here that the literature on regions offers interpretive models, for the works I have cited on the history and identity of regions are about seeking out conceptual maps, through the clash and demise of empires.

I do not offer a ‘background’ essay, synthesised from recent scholarship and older works; I proceed, instead, to map the activities of my key protagonists against a palimpsest of shifting political formations, commercial and military circuits and physical environments. The method here is inductive – the description of the relevant ‘region’ proceeds from the material itself, from the distribution of persons, activities, locales and stories within that material. In that effort, the concept of dāi’ra, which includes the meaning of jurisdiction but circles far beyond it, appears to me to be a useful tool.

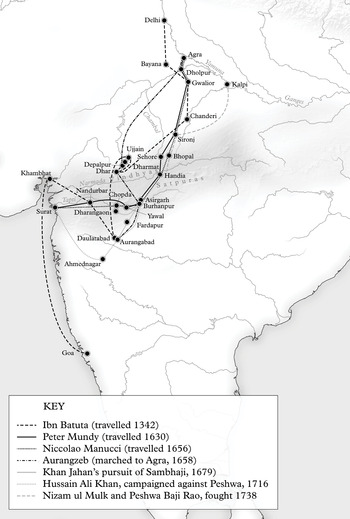

The word dāi’ra, which exists in Arabic, Persian as well as Hindi/Urdu, encompasses a range of meanings related to space and its encirclement. Derived from the Arabic root d-vav-r, it is part of one of those highly fecund word constellations which make Arabic such an evocative language; related words range from geometric to maritime and administrative. Dāi’ra itself, in all three languages, can be a circle, but its meaning also extends to other encircled spaces, such as a camp or monastery, and to spaces circumscribed in the abstract, that is, jurisdiction. In the thirteenth century, the historian Al-Juzjani, patronised by the Delhi Sultan Nasir al-Din, had placed Delhi at the centre of the dā’ira of Islam.Footnote 17 It is this semantic range – encompassing physical, social, architectural and legally defined space – that makes dāi’ra a useful conceptual tool for thinking of the zone of entrenchment and operations represented by Map 1.1.

Property owned by the family – in the form of houses, tax-free grants of agricultural or garden land, as well as various claims on shares of taxation – was clustered in south-western Malwa, just north of the Narmada river, nestling into the hills and forests that partially encircled it from the west and the south (see inset for details). This was the centre of their dāi’ra, but their long arms reached southwards, eastwards and northwards, with a scattering of property in the Mughal centre of Burhanpur, and with intelligence and political networks stretching towards pan-regional political centres: Agra in the Mughal period, Gwalior and Calcutta later. It was within the core area that the protagonists of this story owned and claimed property, fought most of their battles and lived out their lives. But the offshoots of their interests indicated that their dāi’ra was embedded in several other territories – ecological, political, commercial, military and administrative. The work of this chapter is to offer a palimpsest of those maps, as they are crucial for locating the characters of this story and for understanding what they did and said.

Malwa: the Identity of a Region

The dāi’ra of Mohan Das and his family revolved around a dense cluster of villages in district Dhar, in the south-west corner of Malwa, nestling to the north of the Narmada river, the traditional dividing line between Hindustan and Dakhin. The range of their activities fanned out much further, however, with consequent entitlements scattered over a large part of Malwa. As twentieth-century colonial surveys noted, within the sprawling and politically fragmented zone of central India, Malwa formed a distinct region, geologically distinct for being a plateau as opposed to the hills to its west and the ravines to its east.Footnote 18 From at least Tughlaq times, that is, the fourteenth century, Malwa was considered the last frontier of ‘Hindustan’, beyond which began the geologically, linguistically, and politically distinct region of ‘Dakshin’.

Geologically, there were both mountain and river boundaries that marked these limits – the foremost being the great river Narmada, which was difficult and dangerous to cross for several months of the year. The Vindhya and Satpura ranges ran parallel to the river, whereas the Aravallis stretched north-eastwards from the Narmada, creating a western boundary. To the north and north-east ran the Chambal, whose deep ravines remain a formidable natural barrier even today. Besides rivers and hills, there were also forests and animals: the hills to the north-west and the region beyond the Narmada river in the south were both densely forested. The region immediately south of the river Narmada was so well-known for its population of tigers, that the district took the Arabic name for tiger: ‘Nimar’. Dhar, in particular, being at the south-western edge of Malwa, nestles in a corner created by forested hills in the west and the Narmada in the south. Geological and ecological challenges were not necessarily just barriers, however. They were also resources for those that inhabited them, among them ambitious soldiering groups who used the challenges of the landscape to entrench themselves, repulse rivals and prey on vulnerable traffic that passed through areas they had made their own.

Sometime around the twelfth century CE, heterogeneous nomadic and martial groups, including those that originated outside the subcontinent, began to cohere into royal dynasties with territorial claims, paired with genealogical assertions that traced their origins back to fictive progenitors capable of rendering a Kshatriya identity.Footnote 19 Some of these groups, spread from modern-day Rajasthan into central India and along the northern part of the Western Ghats, began to call themselves Rajputs (literally: sons of kings, or princes). Despite active efforts to secure and declare genealogical purity, ‘Rajput’ remained a relatively open social and occupational category well into the sixteenth century, perhaps even the nineteenth in central India, where this story is located.Footnote 20 One such Rajput dynasty was that of the Paramaras of Malwa, established around the tenth century.

Contemporary records of this dynasty, which included the illustrious Bhoja (of the purported Bhojaśālā of Dhar), and Vikramjīt, to whom is attributed the Vikram Saṃvat era, are limited to fragmentary epigraphic evidence (such as the stela of the Ambika statue). Sources from a few centuries later (i.e., the fourteenth century) include Jaina Sanskrit prabandha literature aimed at documenting ideal ‘Jaina’ lives,Footnote 21 and legends reported fairly consistently by Persian-language historiesFootnote 22 focussed on the victories of the Turkic and Afghan warriors, who were establishing a sultanate centred on Delhi at around the same time that the Rajputs were emerging into documented history.Footnote 23 Through the Mughal periodFootnote 24 and by the eighteenth century, the story of Raja Bhoja, Vikramjīt and the Paramara dynasty became a standard part of local lore reported by gazetteers writing in Persian.Footnote 25

As far as administrative history is concerned, Malwa was won and lost by Delhi multiple times since the twelfth century. It was invaded by Sultan Iltutmish in 1233, leading to a plunder of Ujjain and its temples, including the Mahakal temple, which may then have contributed artefacts to the Qutb complex in Delhi.Footnote 26 Control was clearly fragile, for the region had to be reconquered by Alauddin Khalji in 1305 CE, resulting in a historical note by none less than the ‘parrot of India’ Amir Khusrau, the court poet, in his Khazāin al-futuḥ (treasuries of victories). Khusrau noted that on the southern border of Hindustan, Rai Mahalak Deo and his minister Goga possessed around 40,000 horsemen and innumerable foot soldiers. This minister and his king were defeated in an expedition led by Ain al-Mulk, the chamberlain, who then received the province of Malwa under his administration.Footnote 27 However, only a few years later, Sultan Balban appeared to need to subdue Malwa again.Footnote 28

By the early fourteenth century, the geographical area of Malwa settled into the role of a sultanate province, retaining the old capital of Dhar. Composed in the same century, the Gujarati Prabandha-Cintāmani referred to the ‘kingdom of Malwa’ several times throughout the text; this may have been a reflection of sultanate conquest and consolidation of the province as much as a pre-existing regional identity. In 1335, the Moroccan traveller Ibn Batuta went from Delhi to Malabar, passing through Chanderi, Dhar and Ujjain, before proceeding to Daulatabad. He reported that Dhar was the capital of Malwa and the largest district (ʿamala) of the province. He also reported that Dhar was in the iqtaʿ (similar to Mughal jāgīr)Footnote 29 of a certain Shaikh Ibrahim, who had come there from the Maldives. Ujjain, the next stop, was reported as a ‘beautiful city’, graced by a jurist who had come from as far as Granada.Footnote 30

The control of Delhi over the region was fragile; as with Bengal and several other of the regions temporarily overwhelmed by armies from Delhi, Malwa developed into an offshoot autonomous sultanate, such localisation often actuated by the entrenchment of Sufis and soldiers associated with them.Footnote 31 Dilawar Khan, originally appointed governor by Delhi, made use of the disturbance caused Amir Timur’s invasion in 1398 to declare his independence. Although he retained Dhar as his capital, Mandu began developing as a significant political, architectural and military centre, a process enhanced by his successor Hoshang Shah, who is credited with the building of some of the most spectacular buildings in Mandu, including the formidable Mandu fort.Footnote 32 Over the next one hundred years or so, Dilawar Khan’s dynasty, and then that of his cousin and wazīr, Malik Mughis, created and ruled a kingdom whose ever-fluid boundaries were the function of constant alliance and warfare with the sultans of Gujarat, Khandesh and Jaunpur and the Ranas of Mewar, and of deals struck and revoked with the next rung in the political hierarchy: the Rajput zamīndārs, typically entrenched in significant forts. The detailed accounts of constant movement and warfare appear to indicate that contemporary political chroniclers saw the realm as an emanation of the roving king, rather than a settled territory. If we map Malwa in terms of Ferishta’s sixteenth-century account, for example, we see a range of political power, centred on Mandu and Dhar, resting on the forts of Chanderi, Kalpi, Kherla, Keechiwara, Bhilsa (Vidisa), Sarangpur and Raisen, all manned by Rajput and other chieftains, and lunging out towards Baglana, Jaunpur, Chitor, Ajmer, Bundi and Champaran, in a penumbra of power.

At its peak in the fifteenth century, the Malwa Sultanate hosted and patronised several intertwined lines of cultural development, including the Jain religious tradition and literary composition in a language that is now considered old Hindi. The Jain tradition provided a powerful commercial and administrative strand in Islamic Malwa and its penumbra well into the seventeenth century, Muhnot Nainsi of Jodhpur being only the most outstanding example. Such eminence naturally also led to royal patronage as well as private sponsorship of literary and architectural creativity.Footnote 33

Associated with the reign of Sultan Ghiyasuddin Khalji (r. 1469–1501) and his son Nasiruddin are outstanding examples of literary composition such as the Candāyan of Mulla Dā’ud, the oldest known Sufi premākhyan and model for Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s Padmāvat. Written in Awadhi, a non-local old Hindi literary dialect, the Candāyan was a story of travelling in the quest of love, a common trope within the genre; the protagonists were Ahirs – pastoralists with martial aspirations comparable to the Rajputs. The Niʿmat Nāma, on the other hand, is a delightfully epicurean work; a highly illustrated book of recipes bearing testimony to the Sultan Ghiyasuddin’s love of samōsas (and his rather wonderful moustache). Although written in Persian, the Niʿmat Nāma is peppered with Hindi words, and written in what is considered a distinctive Malwa naskh hand.Footnote 34 Alongside Hindi and Persian, Sanskrit too found a place within the sultan’s patronage – a Sanskrit praśastī (eulogy) was written and inscribed on the Suraj Kund tank for Sultan Ghiyasuddin.Footnote 35 Mandu remained the political, military, as well as cultural centre in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries; renamed as Shadiabad or ‘City of Joy’, it represented a regional pride fostered by Malwa sultans.

The Malwa Sultanate eventually crumbled, caught in a three-way imperialist struggle between their old allies/enemies, the Gujarat sultans, the eastern Afghans (Sher Shah Sur and his dynasty) and the incoming Mughals. Malwa was first incorporated into the Gujarat Sultanate and then the Afghan empire; but ironically, it is in that period of political annihilation that it acquired lasting cultural identity, typified by the romantic figure of Baz Bahadur. This Afghan soldier, originally called Bayazid, was the son of an official appointed by Sher Shah, and, typical of governors deputed to Malwa, declared himself independent in 1555. His rule was plagued by overwhelming imperial warfare that ultimately defeated him, but, in the meantime, he acquired lasting fame as lover to a certain courtesan called Rupmati and as a great patron of music. Already a romantic icon to the Mughals, Baz Bahadur may be taken to represent certain key parameters of the distinctive Indo-Islamic culture of Malwa, including its visually striking Afghan orientation.Footnote 36 In 1561, the Mughal emperor Akbar personally led the conquest of Malwa, chasing the unfortunate Baz Bahadur away and causing the demise of his consort. Malwa was settled as a sūba or province of the Mughal empire, with most simmering resistance being subdued by 1570.Footnote 37 The ancient city of Ujjain, titled Dar al-Fath (Abode of Victory), became the new capital of the province.

Routes and Nodes

The Mughal province of Malwa produced some very important cash crops, including the famous Malwa opium, which, the Ā’īn reported, was a common pacifier given to all children up to the age of three.Footnote 38 In a later period, international trade in opium would become the economic mainstay of important post-Mughal Maratha states formed in the region, especially that of the Sindhias of Gwalior; the English East India Company would struggle to control this trade.Footnote 39 The province also included internationally significant cloth-production centres, such as SironjFootnote 40 and Chanderi,Footnote 41 still famous for its sārīs, and was crisscrossed by trade and military routes that connected the Hindustan with the Dakhin and the great ports of the western coast. Those who would travel from Agra to the Indian Ocean port of Surat were prevented from taking a direct route by mountains and forests – the feasible routes were all arcs that swung east before turning west from Burhanpur en route. Of those travellers going from Agra to Surat, those who travelled further south from Burhanpur before turning west usually had some special reason for doing so. In the seventeenth century, an important commercial route was via eastern Malwa, running Agra-Sironj-Burhanpur-Surat and skirting Dhar and Mandu. An alternative, slightly westerly route, favoured by the famous North African traveller Ibn Batuta in the fourteenth century, and by military campaigners including emperor Aurangzeb in the seventeenth, ran via Dhar – the headquarters of our story’s heroes.Footnote 42 As a result, the area saw both a great deal of mobile imperial presence and the activities of local military entrepreneurs who attempted to milk the commercial traffic for protection money.

These north-south-west routes were marked by significant nodes of administration and state presence – in terms of both personnel and architecture. The most significant of these nodes for the protagonists of this story were Ujjain, Asirgarh and Burhanpur, besides Dhar and Mandu. All these locations were marked by significant forts; Asirgarh being purely a fort. Dar al-Fath Ujjain, the capital of the Mughal province, was an old city of both commercial and religious significance, site of the famed Mahakaleshwara temple, which may have been destroyed in the twelfth century by the Delhi Sultan Iltutmish (it would be eventually rebuilt by the Marathas in the eighteenth century). Caravans carrying cloth and other merchandise from Agra, or nearer home, from Chanderi, travelled south-westwards towards Ujjain. From Ujjain, a further move south-westwards brought one to the city of Dhar, and further south-west, to Mandu. Both Dhar and Mandu had major forts; Mandu, the capital of the old Malwa Sultanate, was replete with Indo-Afghan architecture. After Mandu, the major natural barrier was presented by the river Narmada, which was difficult to impossible to cross during the monsoons. After crossing Narmada, however, commercial routes to Surat arced out south-eastwards, to avoid a heavily forested region whose threats are still coded in the district name ‘Nimar’ (Arabic for tiger). The next major stop is the fort of Asirgarh, at the edge of the forested region, and already in the southern district of Burhanpur. This was a pre-Mughal fort, wrested from the Faruqi kings of Khandesh by emperor Akbar around 1600 and formidable enough to hold a part of the imperial Mughal treasury, under the supervision of well-appointed nobles.Footnote 43 More than a hundred years after the British traveller Mundy passed the fort, it played an important role in the Anglo-Maratha wars of the early nineteenth century and was used as a prison for several decades afterwards.Footnote 44 From Asirgarh and Burhanpur, caravans turned westwards, moving via Nandurbar towards the ‘blessed port’ of Surat.

Wars pegged out routes that overlapped with, as well as supplemented, the commercial paths mentioned; spiritual travellers accompanied these armies and caravans. In 1305, Sultan Alauddin Khalji’s general Ain al-Mulk ‘Mahru’ led an invasion that conquered Chanderi, Ujjain, Dhar and Mandu, reaching up to Devgiri (later renamed Daulatabad). The general brought along with him a Chisti Sufi deputed by Nizam al-Din Auliya, who settled in Chanderi and came to be known as Yusuf Chanderi. The great Nizam al-Din is also said to have despatched Kamal al-Din, later known as Malawi, for the guidance of the people of Malwa;Footnote 45 presumably, he travelled by a similar route.

Chanderi, Dhar and Ujjain also figured in the route taken later in the same century by Ibn Batuta, when travelling from Delhi to the Malabar with a commission from the eccentric Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq.Footnote 46 In 1399, when the Chisti saint Muhammad Gisu Daraz, fled from Delhi about to be attacked by Amir Timur, his route from Delhi to Daulatabad via Gwalior and Chanderi must have passed through or close by Ujjain, Dhar and Mandu.Footnote 47 Around two hundred years later, in 1534, the Mughal emperor Humayun passed through Raisin, Sarangpur, Nalcha and Mandu, capturing the fort of Mandu before proceeding to Gujarat in pursuit of the Gujarati sultan.Footnote 48 Ujjain, the capital of the Mughal province of Malwa, was also an important node in this martial/commercial route; in 1658, the future emperor Aurangzeb, moving Agra-wards from Burhanpur, defeated Maharaja Jaswant Singh and despatched by his brother Dara Shukoh at Dharmat, a few miles from Ujjain city.Footnote 49

Map 1.2 Commercial and military routes across Malwa

In the interstices of these great commercial and military movements ran the trade routes of the nomadic banjāras, their trade oriented towards the rural hinterland but substantial in scale nevertheless, carrying grain between villages and offering loans on the way, to be recouped on the return leg of the journey, or in subsequent cycles. The banjāras moved slowly in packs, grazing their cattle as they went, stopping at villages to procure marketable food grains and to sell other goods in return.Footnote 50 Persian-language historians from the thirteenth century referred to them as ‘people of the caravan’ (karvānīs) and occasionally, Delhi-based regimes undertook interventionist measures to control their marketing practices in order to lower and stabilise the price of grain in the capital city. Besides dealing in grain, they frequently accompanied armies, even on very long journeys such Jahangir’s expedition to Qandahar. Presumably, the women and children that the East India Company agent, Peter Mundy, observed when travelling through Malwa,Footnote 51 went along even on those perilous journeys as part of the tanda, as their caravans tended to be called in India.Footnote 52 John Malcolm, appointed Resident in Malwa in the early nineteenth century, noted that, although illiterate, banjāras were known for their capacity of retaining the details of extremely complex transactions in memory.Footnote 53

These acute, itinerant traders were looked down upon by members of more settled castes, and shared the in-between status of several low-ranking ‘service’ castes, such as Dom, Dhanuk and Pasi, who hovered on the outer peripheries of villages, sustaining the village but never quite of it themselves. An encyclopaedic Persian-language ethnographic projectFootnote 54 commissioned in the early nineteenth century by a man who was himself of amphibious standing,Footnote 55 noted that banjāras never lived in the towns or villages, coming and going as they needed. Ethnographic details in James Skinner’s Tashriḥ al-aqwām are not always plausible; the book itself is a curiously artificial effort to align social observations with Brahmanical caste theory of society. Skinner suggested that banjāras were the commercial branch of the community (qaum) of Charans (bards), descended from an instance of miscegenation (varnasamkara) between a Bhat woman and a trader (baqqāl), and also that some banjāras worshipped a goddess named Sri Devi, while others were Muslims. Whatever their precise sociological and ritual dispensation, banjāras make several fleeting appearances in this story.

The Rajputs of Malwa

The conjunction of war-filled landscape, difficult terrain and busy routes carrying valuable merchandise as well as competing armies led to the social entrenchment and, hence, administrative and military function of a range of local chieftains, many of whom identified as Rajputs. All supra-local regimes that jostled each other in Malwa had to contend with these suppliers of armed manpower and with aspirants to royalty. These warlords used the difficulties of the terrain as their resources, inhabiting forts marking key nodes in the martial and commercial routes that traversed those terrains. This was a process of political formation that rested simultaneously on territory and mobility; all empires that wanted to control Malwa had to control these nodes. The process was wobbly, because these local powerholders were simultaneously oriented towards multiple arcs of power and deference; they need constant wooing and awing.

As they offered their services to multiple regimes, these Rajput warlords of Malwa, especially those famous as the ‘Purbiya Rajputs’ – struggled for equivalence with Turko-Afghan Muslim aristocrats, emulating their lifestyles and households, while also seeking translocal marriage alliances with more successful Rajput groupsFootnote 56 and genealogical self-aggrandisement, specifically through the patronage of bardic groups known as charans and bhāṭs.Footnote 57 For their part, the Malwa sultans appeared to fully endorse the claim attributed to one famous Purbiya Rajput of Malwa – Silhadi Purbiya – that ‘for generations we have de facto enjoyed the essence of the sultanat’.Footnote 58 But the Rajputs held back from seizing sovereign authority themselves, recognising that this would mobilise internal and external resistance; it appeared to them wiser to keep the Malwa sultans on the throne. And in this way, a prolonged, intense but mutually cautious courtship was initiated.

When the second Malwa sultan, Hoshang Shah, was captured from the fort of Dhar and taken away to Gujarat in 1407, the Malwa ‘chiefs’ (possibly Muslim and Hindu) rose in rebellion against the governor appointed by Gujarat, chasing him away and killing a part of his army, before ensconcing themselves in the fort of Mandu. This display of support led to Hoshang Shah’s release; back in Malwa, he was able to secure the support of some soldiers immediately but that of others only after fighting them. When the restless Gujarati sultan attacked the tiny Rajput principality of Jhalawar in 1413, on the north-western boundary of Malwa, the chief appealed to Hoshang for help, providing him with an excuse for counter-aggression. Rajput loyalty was untrustworthy still, and so Hoshang found himself beating a hasty retreat when the rāja of Jhalawar made no effort to assist him. In 1418, however, when Gujarat started ravaging Junagadh, Hoshang’s support appeared more valuable to these principalities, and the rājas (Rajput chiefs) of Jhalawar, Champaner, Nadot and Idar, that is, in a full arc on the north-western borders of Malwa, appealed to him, shamefaced for their ‘neglect and dilatoriness’ in the first occasion, but promising full support in the current campaign against Gujarat. Clearly, they knew the value of local knowledge, for they offered to take him through such a route to Gujarat that the Sultan of Gujarat wouldn’t know what hit him. However, even this time, the rājas did not quite deliver on their promise, leading to an ignominious retreat for Hoshang.Footnote 59 Some of these rājas were capable of raising formidable armies of their own, and had access to crucial war animals, especially elephants. Such rājas continued to be self-serving allies, changing overlords whenever suitable, and extending their effective territories as soon as such overlords appeared distracted or weakened. The Sultanates of Malwa, Gujarat and the Bahmanis remained constantly subject to their capricious loyalty.

The Afghan Surs and the Mughals continued the same process of co-option and attrition with the local rājas in their subsequent efforts to control Malwa. Humayun marched through Malwa in 1535 on his way to Gujarat, apparently with the support, or at least acquiescence of the rājas of Raisin, and had the Rajput qilaʿdār of Mandu opening the gates of that formidable fort for him. Thus strengthened, he met the Gujarat army at Mandsaur, and won Malwa for the Mughal dynasty but apparently with a restricted social base of support, requiring a general massacre in Mandu.Footnote 60 Rivers of blood were an inadequate foundation for permanent rule, and Humayun soon found himself out of Malwa. Following Humayun’s expulsion, the Surs entered Malwa, and this time the rājas of Raisin appeared to be less hospitable. In Sher Shah’s violent battle in Raisin in 1543 against the Chanderi rāja, Puran Mal, there was a certain amount of spectacular carnage directed against this powerful clan, justified by an ʿalīm who offered a convenient fatwā justifying the breaking of safe-passage promises and the slaughter of infidels.Footnote 61 Soon afterwards, however, Sher Shah was able to detach a section of the Rajput followers of Maldeo, the ruler of Jodhpur, prior to a crucial battle.Footnote 62

The Mughals continued and refined this policy. Certain clans of Rajputs were raised by the Mughals to the highest non-princely imperial service ranks, or mansabs, granted special privileges such as service land-grants in their home countries (waṭan jāgīrs) and even anointed with the title Mirza, which purported kinship with Timur and hence the Mughal royal house. Thus, a select few among these warrior clans developed a resource-base and identity that was inseparable from the Mughal power and courtly culture.Footnote 63 For the majority, however, the Mughal technique was a combination of reconfirming old grants made by previous regimes, but also social engineering; for example, by moving branches of Rajput clans from Rajputana into the sūba of Malwa through service grants, specifically awarded to such recruits that managed to defeat other Rajput leaders less amenable to imperial absorption.Footnote 64 In the interstices of these imperial efforts, there took place the formation of little polities. Looking at these processes of political crystallisation offers us an additional perspective beyond that of the dynamics of the military labour market. It is worth looking at a few such examples of Rajput principalities surrounding the region in which our story is set in order to map out the political and social geography of the region.

The best-known of such sub-imperial Rajput principalities in the region lay just outside Malwa, in the area known as Bundelkhand. The Bundela principality of Orccha appeared on the political map in the early fifteenth century. Incompletely subdued and eventually killed in 1592, Madhukar Shah of Orccha remained a problematic recruit for Emperor Akbar. Constantly bickering and land-grabbing, his many sons and purported heirs were no better tamed.Footnote 65 Eventually one of these sons, Bir Singh Bundela, when pressed into imperial service in the Deccan, would abscond and take himself to the rebellious crown-prince Salim’s camp in Allahabad, and purchase the latter’s patronage by murdering Akbar’s wazīr, Abul Fazl. In these years, the road between Gwalior and Ujjain was said to be so dangerous, that even imperial agents felt nervous, and brave Rajputs allied with the imperial court chose to travel by the cover of night and hide during the day.Footnote 66

However sordid the origins of his prosperity may have been, with Mughal blessing, Bir Singh built himself up as a great king, and offered valuable patronage to litterateurs. Such patronage turned Orccha into a centre of courtly Hindi (Braj) poetry, which the classically (i.e., Sanskrit-trained) court poet Keshavdas used to put new wine in old bottles – producing a Braj praśastī of emperor Jahangir in good old Sanskrit style in Jahāngīrrasacandrikā.Footnote 67 However, continued loyalty during the next succession battle led Bir Singh into the wrong side, and his son and heir Jujhar Singh found himself and his estates under severe scrutiny by the once-rebel Khurram, now emperor Shah Jahan. Pushed to rebellion, Jujhar Singh and his son fled to their home territories, pursued by a huge imperial force. The fort of Orccha was stormed, and when Jujhar Singh fled with his injured son into the jungles to the east of his dominions, the neighbouring Gond tribes revealed that there was no love lost between them and the Rajput chiefs by killing the men.Footnote 68 The conquering general Khanjahan’s secretary, Jalal Hisari, wrote a terse ‘sociological’ history of this clan-turned-kingdom-turned rebels, noting that the qaum of Bundelas had came from Bundi, reproducing what might have been a common trope of attributing locational origin and lineage based on phonetic rather than substantive genealogical connections. Hisari continued by recounting that the Bundelas had grabbed possession and dominance in many villages and towns, and some had declared themselves rājas, including Madhukar. The relation with the Mughals remained patchy, leading to almost inevitable rebellion and destruction by Mughal forces.Footnote 69

We have less-detailed accounts of other such kingdoms, but the glimpses we are offered confirm that same pattern of warlordism and functional alliance with empire builders, occasioning inadvertent cultural intermingling. Another Bundela, Chhatrasal, formed the breakaway kingdom of Panna in 1657, and eventually rebelled against the Mughals to ally with the arch-rebels, the Marathas. The connection with the Marathas was substantiated by a significant marital alliance – Chhatrasal’s daughter ‘Mastani’, now with a Bollywood blockbuster to her name, was married (or gifted) to Peshwa Baji Rao I, who brought the fight to the doorstep of the Mughals.Footnote 70 In his own lifetime, and contrary to current Bollywood imagination, however, the Bundela king proved as susceptible to the lure of imperial service as any other military entrepreneur, and was found in the imperial army led by Jai Singh in Malwa, in 1714.Footnote 71

On the western edges of Malwa lay Bundi – the reputed original homeland of the Bundelas. Its ruler, Budh Singh, made significant progress towards the latter part of the Aurangzeb’s reign. Playing his cards carefully, he sided with Prince Muazzam during key moments and, through the latter’s recommendation, gained the districts of Patan and Tonk. He, too, was part of Jai Singh’s anti-Maratha army in 1714.Footnote 72 In central Malwa, Sitamau was an outright imperial creation, rising on the ruins of Ratlam – through confiscations and grants made by Aurangzeb to a loyal member of a Rāthoḍ clan that was otherwise prone to disaffection.Footnote 73 Baglana, to the south of Tapti, was also a principality created by long-ensconced hill-chiefs who acquired a ‘Rajput’, specifically Rāthoḍ, genealogy in the sixteenth century. Buoyed for a period by Mughal support, they attacked their neighbours and expanded their own realm, until they were annexed by a southward thrust by the prince Aurangzeb. This annexation let loose a host of subordinates who were eventually overrun by the rising Maratha empire in the late seventeenth century.Footnote 74

Thus, Rajput warlord kingdoms ranged all over north-western, northern and central India, forming a left-leaning C-arc around the heartland of the Delhi Sultanate and, later, the Mughals. Clans branched, migrated and formed multiple small and large principalities, which would only much later be connected through genealogical exercises. In the eighteenth century, with the faltering of Mughal control and patronage, and the rise of the Maratha empire, all such sub-imperial polities in Malwa were incorporated into one or another of the states established by the Maratha generals. After the 1730s, even the grand Rajput kingdoms of Jodhpur, Jaipur and Mewar were dominated by the Marathas, who used the Mughal policy of undercutting them by participating in factional squabbles and encouraging the next rung of feudatories.Footnote 75

Only in the nineteenth century, through British romanticisation, as well as the circumscription of political and military power, did Rajputs become specifically associated with Rajasthan (literally, Hindi/Persian: the land of kings) – putative homeland for Rajputs. Tod, first Resident at the court and camp of the Maratha general Daulat Rao Sindhia, and then political agent to the Western Rajput States from 1818, celebrated British achievement in separating the various warrior groups and breaking their kinship and patronage networks, all of which he framed in a nation-centric narrative of freeing the Rajputs from the control of the foreign Marathas.Footnote 76

Thus, until the nineteenth century, Malwa was an integral part of that mobile and martial political geography, which was marked as the land of Rajputs (western Rajasthan) through the pan–north Indian folk epic of Dholā-Māru.Footnote 77 The Rajasthani-language versions tell the story of Prince Dhola’s two wives, Maru (or Marvani, of Marwar) and Malwani. His journey from one to the other and back represented the twinning of the two Rajput sub-regions, as well as the circulation of martial males between them. In the seventeenth century, when the Dholā-Māru story was achieving a stable manuscript form in connection of Rajput courts of Marwar, the story of the derivative nature of Malwi Rajputs, and their de-racination through assimilation with local customs appears to have been popularised by Rajput nobles who had recently moved into the Malwa, backed by Mughal imperial appointments and grants.Footnote 78

Ranbaṇkā Rāthoḍ

Among all these Rajputs clan-kingdoms, those that claimed Rāthoḍ genealogies have a significant role to play in this story. Right next to the district of Dhar were the principalities of Jhabua and Amjhera – both ruled by Rāthoḍ clans. The ruler of Jhabua had been reinstated by Shah Jahan in 1634, after a period of disturbance.Footnote 79

The kingdom of Amjhera claims as its mūlpurūsh, Rao Ram (1529–74 CE), who, following a dispute over succession, invited emperor Akbar to intervene in Jodhpur. Rao Ram’s grandson, Rao Jaswant Singh is said to have moved to Malwa, to (a now untraceable) fort called Morigarh, and his son, Keshavdas, received a host of grants in south-west Malwa, leading to the effective establishment of the state of Amjhera.Footnote 80 Several generations later, Jagrup Rathor provided active service to the governor Nawazish Khan in clearing the area, and was rewarded with a mansab.Footnote 81 This man’s son, Jasrup Rathor, will make a rather sanguinary appearance on our story.

Of these typically fissive groups, whose common motto (virad) is the claim of being unflinching in war (raṇbaṇkā), those that settled in Marwar,Footnote 82 and especially the Jodhpur branch, rose the highest within the Mughal nobility and royal family. This line is now unsurprisingly the claimant of the highest genealogical status among Rāthoḍ – considered a kind of mother house.Footnote 83 Success within the Mughal imperium appears to have gone hand in hand with the production of chronicles by court-sponsored bards known by the caste name of charan and bhāṭ, which, again predictably, erased as much of the feudal dependency as possible, in creating the story of these autochthonous royal houses.Footnote 84

Together, such processes blur any border that we might now imagine between the modern Indian states of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.Footnote 85 They also, unsurprisingly, blur the boundaries between state and society, for such local recruits and implants were essentially warlords whose loyalties depended on the balance between the relative benefits of imperial service and local autonomy, which in turn depended on the size of their retainer armies and hence the possibility of military success. As constant shoppers for better deals, they represent that persistent turbulence but also a source of state-formation, which André Wink has called fitna.Footnote 86

Girāsiyas and Afghans

There were other martially oriented corporate groups that thrived in the ecology of Malwa but were less successful in turning their war zones into polities. Among these were armed groups such as girāsiyas claiming mixed Bhil (hill-based warrior groups) and Rajput ancestry. Scholars have long been confused about the precise ethnic connotation of the term girāsiya, which occurs several times in the documents of our collection. The military historian Irvine considered them hill tribes, but Raghuvir Sinh, based on Malcolm, asserted that these were outlaw Rajputs.Footnote 87 Malcolm himself noted unequivocally that the ‘Grassiah’ chiefs were all Rajputs, but of the category that had been dispossessed and thus eked out a living through predatory raids.Footnote 88 The connection with Rajputs and landed power also held in the neighbouring region and province of Gujarat, which also shared the common story of girāsiya stemming from a derivative of grās – a mouthful – implying a share in land rights. In the eighteenth century, the term, and the group named by it, became associated with robbery and protection rackets.Footnote 89 Despite such decline in fortunes, at least some of the girāsiya chiefs were significant enough even in the early nineteenth century for the East India Company to conclude treaties with them, protecting their claims on major princely states such as the Holkars.Footnote 90

This was one of the inner frontiers of any empire that claimed the region, including those of the Mughals. Quite like the Sahyadri hills (Western Ghats), about which Sumit Guha has written, the turbulence of Malwa, north of the Narmada river, implied both an endless source of cheap military labour and subversive sources of alternative royal legitimacy, with its own kings, bards and genealogical myths.Footnote 91 The professions and fortunes of such militarised marginal groups changed for the worse during the processes of colonial and national sedentarisation; an unimaginative postcolonial anthropological study took the view that these were people of ‘backward’ tribes, bearing no possible connection with the Rajputs.Footnote 92

Afghans were another locally significant martial group whose occupations and status extended towards royalty on one side and robbery on the other, albeit with a wider geographical and social range than the girāsiyas. At least some Afghan chiefs saw their identities of a piece with that of the Rajputs, demonstrated through their choice of titles such as rāwat, and their genealogical stories.Footnote 93 The first Afghan kingdoms in Malwa were formed as the offshoots of the dynasty and polity of the Delhi Sultanate, especially the Khaljis. The term ‘military market’ applies particularly well to Afghans, who maintained a dominance over the supplies of military war horses for several centuries, and also supplied a constant flow of recruitable soldiers, frequently aspiring for more than ‘naukarī’. Derived from a Mongol word – nökör – implying retainer/faithful companion/friend, naukarī itself was always more than service anyway. It was a concept of political ability and loyalty, popularised around the fifteenth century, which continued to jostle with other concepts that it was related to – especially bandagī (servitude), which under the Delhi sultans and their provincial counterparts had lent itself to the politically elevated bandagī-yi khās or the specially favoured slave, ex-slave or quasi-slave retainer. Afghan kings struggled with warbands and their leaders, all determined to assert brotherhood and equivalence; certain Afghan warlords were known to have addressed the emperor Bahlol Lodi, himself descended from horse-traders, endearingly (or threateningly) as Ballu.Footnote 94 In Malwa, the eastern Afghan Sur empire held sway for brief period in the mid-sixteenth century before Akbar, and the Mughals, took over in the 1570s.

The next political resurgence of Afghans in Malwa, albeit a limited one, coincided with imperialist invasions from the north-west, that of the Durranis, in the 1760s. As with previous conflicts between mobile martial groups, the temporary damage caused to the Maratha empire by that Afghan invasion did not constitute any permanent ethnic opposition. Afghan soldiers flourished under the Maratha sardārs (warlords-turned-kings), and, as the Maratha polities crumbled, at least some of them formed part of that motley bunch of freebooters the British called the Pindārīs. The campaign against the Pindārīs, which brought the British into power in central India, was equally directed against their sponsors, the Marathas.Footnote 95 Some parts of this mercenary mass congealed into more stable polities, most importantly, at Tonk, with an Afghan dynasty at the helm.Footnote 96 The kingdom of Tonk was particularly connected with Malwa, given the founder, Amir Khan’s vassalage of the Maratha general Jaswant Rao Holkar, whose state was headquartered at Indore.Footnote 97

Not all Afghans in Malwa were kings, soldiers or even military horse-traders; there was a small but significant settlement around the tomb of Kamal al-Din Chisti, whose legacy, and that of other Chisti and Shattari Sufis, graced the city with the name Dar al-anwar pirān-i Dhar.Footnote 98 Soldiers and religious adepts were often part of the same migratory episodes; such a family, associated with Dhar and other central Indian Afghan Sufi centres, might even have produced a Bollywood superstar.Footnote 99

Other Empires: Marathas and British

By the early eighteenth century, this south-western district of Malwa was subjected to repeated Maratha invasions, whose empire spread all over the province and incorporated it after the Mughal farmāns (royal orders) of 1741 formally appointed Peshwa Balaji Rao deputy-governor of Malwa.Footnote 100 Mughal recognition lagged behind political realities: Malwa had been subjected to periodic Maratha raids from the 1690s, and, in practical terms, passed under the control of Maratha sardārs in the early eighteenth century. Three generals and their dynasties established the most significant Maratha kingdoms in Malwa – the Holkars, with the headquarters in Indore; the Sindhias, headquartered in Gwalior; and the Puwars with their dominion in Dhar and Dewas. The substance of these new polities was a matter of prolonged battles and negotiation, with competing and mutually contradictory grants from the sovereigns of competing sides (the Mughals and the Marathas).

As a corollary of this process, Rajput clans in the region changed loyalties, but some of the new Maratha overlords also began to claim to be Rajputs. Such was the case with the Puwars of Dhar, as well as the genealogically associated states of Dewas Senior and Junior.Footnote 101

It was from the fragmented Maratha kingdoms of the region that the British eventually formed the Central Indian Agency in the early nineteenth century. Appointed its political and military head for four years from 1818, John Malcolm would produce the most comprehensive political survey of the region, which revealed the area as a shatter-zone in the clash of empires.Footnote 102 Dhar emerged as one of the princely states in the region, under the control of the Puwar dynasty, its territories braided with the much larger possessions of the Holkars of Indore and Sindhias of Gwalior.

Conclusion

Malwa was a land of layered empires from long before the advent of the Mughals in the Indian subcontinent. The family whose story this book tells was distinctive in surviving several changes of regimes: claiming to be present in the region even during the Malwa Sultanates, they outlasted the Mughals, the Marathas as well as the British, retaining documentation of their rights until the present day. Through those documents we can approach the working of empires from underneath, and discover how significant rights-holders situated just beneath the shifting imperial structures entered and extracted themselves from those polities, and what notions of selfhood and entitlements they retained throughout that process of shifting loyalties.