Introduction

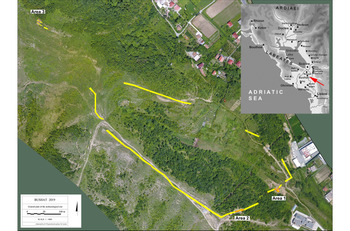

The investigations in Bushat are part of a large scale research project in the territory of Shkoder (antique Scodra), in modern-day northern Albania. The project has been underway since 2011 under the direction of the Institute of Archaeology in Tirana, in collaboration with the Antiquity of Southeastern Europe Research Centre at the University of Warsaw, Poland. The Illyrian past of Albania is a focus of the project. Shkoder was thought to be the Illyrian capital in the times of King Genthios; this theory was tested by investigations between 2011 and 2015 (Lemke Reference Lemke2015; Dyczek & Shpuza Reference Dyczek, Shpuza, Lamboley, Përzhita and Skënderaj2018). From 2016, the focus shifted to the various settlements around Shkoder; these were surveyed thoroughly (Shpuza Reference Shpuza2014, Reference Shpuza2017). As a result of these surveys, the site of Bushat was chosen for further investigation including fieldwork (Figure 1). This decision proved fruitful, and after the 2018–2019 fieldwork seasons we were able to report two stretches of a massive fortification wall securing a hitherto unknown Illyrian settlement.

Figure 1. Orthophotomap showing an aerial view of the Bushat site (by B. Wojciechowski & M. Lemke); inset: map of northern Albania in antiquity (map S. Shpuza).

Geography

The geography of Bushat is peculiar. The archaeological site lies on the southern slopes of an elongated elevation with three hilltops, just north of the modern Albanian village sharing the same name. It is a rare high point in an area otherwise consisting of level plains, shaped by the current and former riverbed of the Drin (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The hill-chain of Bushat viewed from the west, beyond is the River Drin (photograph by M. Lemke).

The Illyrian settlement was located on two ridges running towards the southernmost hilltop (195m asl) and in a small valley between them (65m asl), surrounded by a fortification wall. The walls ran up the hill despite the considerable gradient, forming an irregular triangle enclosing an area of around 20ha (Figure 1), which corresponds to a middle-sized Illyrian city of the Hellenistic period in the region. Some structures were also noted outside the walls during the surveys. It is important to note that from the hilltops of Bushat there is a clear view to a number of settlements in the north and east, including Scodra (Shpuza Reference Shpuza2017: 48). With this intervisibility in mind, the lonely hill-chain of Bushat must have been the perfect place for a settlement.

Fieldwork 2017–2019

Excavations in 2018 and 2019 were preceded by a very thorough survey, including geophysics in 2017. The results showed that the fortification wall is better preserved on the western flank of the site, where it can be followed in two continuous sections of 30 and 70m long.

The wall is constructed using a technique very characteristic of Hellenistic defensive structures generally and of the Illyrian region in particular: large, well-fitted stone blocks creating impressive defensive walls. While the exterior façades were made of profiled stone blocks, the core of the wall was filled with smaller stones and earth, and was intersected by crude partition walls in a technique called emplekton. The best example of this in the vicinity is at Lissos, to the south-east of Bushat (Oettel Reference Oettel, Matthaei and Zimmermann2015: 240–41). Interestingly, three different kinds of stone were used for building these walls: conglomerate, limestone and sandstone (Shpuza Reference Shpuza2017: 49). All three have been noted in the geology of the hills of Bushat. Conglomerate stones seem to have been used particularly for the upper part of the fortification (area three), and the preparation of the blocks shows skilled craftwork, as this type of stone is difficult to work with. Sandstone appears to have been used mostly in the western part of the fortification wall, probably for logistical convenience, while limestone is the most frequently used construction material.

Three areas were chosen for excavation. Area one (Figure 3) is located near the south-eastern corner of the site, in the valley between two ridges. This area turned out to be the location of an entrance gate (2.30m wide), which was flanked by a single tower. The two stretches of the wall run almost perpendicular to the gateway, forcing the people entering to walk alongside the fortification for some distance—another typical characteristic of Illyrian defences. In the excavated area of roughly 300m2, the wall is very well preserved, up to a height of over 2m in some places, and the same can be said about the internal structure of the wall, which allows for a thorough analysis of the emplekton. The width of the wall is 3.50m.

Figure 3. Area one: above) looking towards the hilltop; below) the fortification wall with gate and tower (photographs by M. Lemke).

Excavation of area two (Figure 4) revealed another gate, located in the central part of the city, 150m to the south-west of area one and 30m up the slope of the hill. An area of 30 × 8m was excavated. The wall here is preserved only at a foundation level for most of the section, but the construction technique and dimensions (width: 3.50m) are the same as in area one.

Figure 4. Aerial view of the fortification wall in area two (photograph by M. Lemke).

Excavation was also undertaken on the highest of the hilltops towering above the site (area three), where a stone platform surrounded by a fortification wall was discovered (Figure 5). Corinthian-type tiles demonstrate that there was a significant building here, whose character is still difficult to determine. The fortification wall here is different in technique from the sections in areas one and two; here there is only an external façade and a backfilling behind it roughly 2m wide.

Figure 5. Area three: the fortified platform on the hilltop, and in the background, the floodplain of the River Drin (photograph by M. Lemke).

In all three trenches, but particularly at areas one and two, considerable amounts of Hellenistic pottery were found. These consisted largely of amphorae (with the MGS IV type dominant—this is very common in the Adriatic), but also kitchen ware and black gloss table ware (Figure 6). Based on the pottery and other small finds, including a coin of Demetrius I of Macedon dated post-304 BC, the site was dated to the fourth to third centuries BC.

Figure 6. Hellenistic pottery from Bushat (photographs by J. Recław & A. Miernik).

Bushat in context

Our investigations indicate that the foundation of this city took place at the same time that the big urban centres at Scodra and Lissos were thriving: the end of the fourth and beginning of the third centuries BC. The existence of no less than three cities in a territory of approximately 350km2 is proof that civic life in Illyria was already significant at the beginning of the Hellenistic era. Slightly more recent than these cities are a high number of ‘rural’ fortifications, which become very common about a century later, during the long period of insecurity that began with the wars of queen Teuta against the Romans (229 BC) and lasted until the last war of Genthios (168 BC) (Shpuza Reference Shpuza2017: 50–60). The broad landscape surveys in the area around Scodra provide a better framework for understanding the organisation of space and the relationship of the Illyrian cities to their hinterlands. In the case of Bushat, the general triangular layout of the fortification is quite comparable to the fortification of Zgerdheshi (Albanopolis), where most of the towers are also situated in the lower part of the fortification (Metalla & Maurer Reference Metalla and Maurer2018). At the same time, Bushat is an important case study for the process of Hellenisation taking place in Illyria, which had not belonged to Alexander's Empire, but gradually absorbed Greek influences, as evidenced by the architecture and pottery. Future investigations will hopefully provide further details that will help us to understand the development of this site more fully.

Funding statement

The project ‘Albanian-Polish Archaeological Research in the Illyrian Capital Scodra and its Economic Hinterland in Antiquity’ was funded by the Polish National Science Centre, UMO-2014/14/M/HS3/00741.