The Mental Health Act 1959 followed a groundbreaking Royal Commission and marked a transition from legalistic forms to paternalism. Mental health professionals were given wide latitude to act in the health interests of people with mental disorders. The Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA) curtailed some of these powers and strengthened patients' rights against paternalistic intrusion. The 1990s has seen yet another shift; ‘community care’ has frightened many into a preoccupation with ‘public safety’ and seeking means of exerting more control over patients, especially to ensure their compliance with treatment in the community (Department of Health, 1998, 1999). Such swings of policy remind us that the prescription of involuntary treatment is primarily a social matter and only weakly related to the epidemiology or clinical features of mental disorder. Why else should the rate of compulsory admissions in this country have almost doubled since 1980 (Reference Wall, Hotopf and WesselyWall et al, 1999) or currently stand at about twice the rate in Italy (49 per 100 000 v. 26 per 100 000 population per annum), despite similar service configurations (Reference de Girolamo and Cozzade Girolamo & Cozza, 2000)?

Community care has stimulated rethinking of the role of mental health legislation. By so doing it has exposed hidden assumptions in past legislation that discriminate against those with mental illnesses (Reference Campbell and HeginbothamCampbell & Heginbotham, 1991; Reference Szmukler and HollowaySzmukler & Holloway, 1998; Department of Health, 1999).

SOME FUNDAMENTALS: ‘CAPACITY’ AND ‘BEST INTERESTS’

An Expert Committee set up by the Government in 1998 to advise on reform of the MHA endorsed two fundamental principles: non-discrimination against those with a mental illness, so they are treated like those with other illnesses, and respect for patients' autonomy (Department of Health, 1999). This led to a reconsideration of the grounds of involuntary treatment in general and to the conclusion that this must be connected with a patient's lack of capacity to make treatment decisions. ‘Capacity’, put at its simplest, refers to the patient's ability to understand the nature and purpose of the recommended treatment, including the consequences of having or not having it, and to reason using this information (Law Commission, 1995; Reference Grisso and AppelbaumGrisso & Appelbaum, 1998).

By any standards, the Committee complied with the Government's demand for a ‘root and branch’ reassessment of the MHA: it recommended radical and far-reaching revisions — far too radical, it now appears. Table 1 summarises the key recommendations and, for comparison, the Government's proposals in the Green Paper (Secretary of State for Health, 1999). As Table 1 shows, the Green Paper finds capacity unattractive; the overarching principle is to reduce the risk of harm — to the patient and especially to others. However, where this principle comes from and why it should be primary is unexplained.

Table 1 Key recommendations by the Expert Committee compared with the Government Green Paper

| Expert Committee Report (Department of Health, 1999) | Government proposals for reform of the Mental Health Act 1983 | |

|---|---|---|

| Principles | Overarching principles of non-discrimination and autonomy | “ The degree of risk that patients with mental disorders pose to themselves or others,…is crucial…in the presence of such risk, questions of capacity may be largely irrelevant to…whether or not a compulsory order should be made”. |

| Diagnostic criteria |

|

Accepts Committee's recommendations |

| Criteria for compulsory care and treatment | “ The presence of mental disorder of such seriousness that the patient requires care and treatment under the supervision of specialist mental health services; and that the care and treatment proposed for, and consequent upon, the mental disorder is the least restrictive and invasive alternative available consistent with safe and effective care; and that the proposed care and treatment is in the patient's best interests; and either that, in the case of a patient who lacks capacity to consent to care and treatment for mental disorder, it is necessary for the health or safety of the patient or for the protection of others from serious harm or for the protection of the patient from serious exploitation that s/he be subject to such care and treatment, and that such care and treatment cannot be implemented unless s/he is compelled under this section; or that, in the case of a patient who has capacity to consent to the proposed care and treatment for her/his mental disorder, there is a substantial risk of serious harm to the health or safety of the patient or to the safety of other persons if s/he remains untreated, and there are positive clinical measures included within the proposed care and treatment which are likely to prevent deterioration or to secure an improvement in the patient's mental condition”. | “ The presence of a mental disorder of such seriousness that the patient requires care and treatment under the supervision of specialist mental health services; and that the care and treatment proposed for the mental disorder, and for conditions resulting from it, are the least restrictive alternative available consistent with safe and effective care; and that the proposed care and treatment cannot be implemented without use of compulsory powers; and that the care and treatment are necessary for the health or safety of the patient; and/or for the protection of others from serious harm; and/or for the protection of the patient from serious exploitation”. |

| Processes |

|

|

| Discharge and after-care |

|

|

| Offender patients |

|

|

We agree with the Expert Committee that ‘capacity’ is key to the whole frame-work of mental health legislation. Thorny definitions of ‘mental disorder’ recede in importance in decisions about involuntary treatment. More important are two questions: does the patient lack the mental capacity to make treatment decisions for him or herself (capacity is normally presumed), and if so, are the patient's best interests served by imposing treatment? Hence, the Committee accepts a broad definition of mental disorder. ‘Capacity’ also forces us to tackle blurred distinctions hidden behind the familiar coupling that treatment is necessary ‘for the health or safety of the patient’ or ‘for the protection of others’.

‘PATERNALISM’ V. ‘PROTECTION OF OTHERS’

‘Paternalism’ is concerned with the health interests of a patient. It is accepted in medicine (with the notable exception of psychiatry) that others are empowered to act only when the patient lacks capacity and there is reason to believe that treatment without consent, or against a patient's objections, is in the patient's best interests. The goal is restoration of health, and if possible the patient's autonomy (or capacity). What is in the patient's best interests is determined by asking a range of questions aiming to determine what the patient might have chosen in this situation were he or she not lacking in capacity. Previously expressed wishes, preferences or values (for example in an advance statement), including the evidence from others concerning these, are especially important (Law Commission, 1995). Note that ‘best interests’ adopts the patient's perspective.

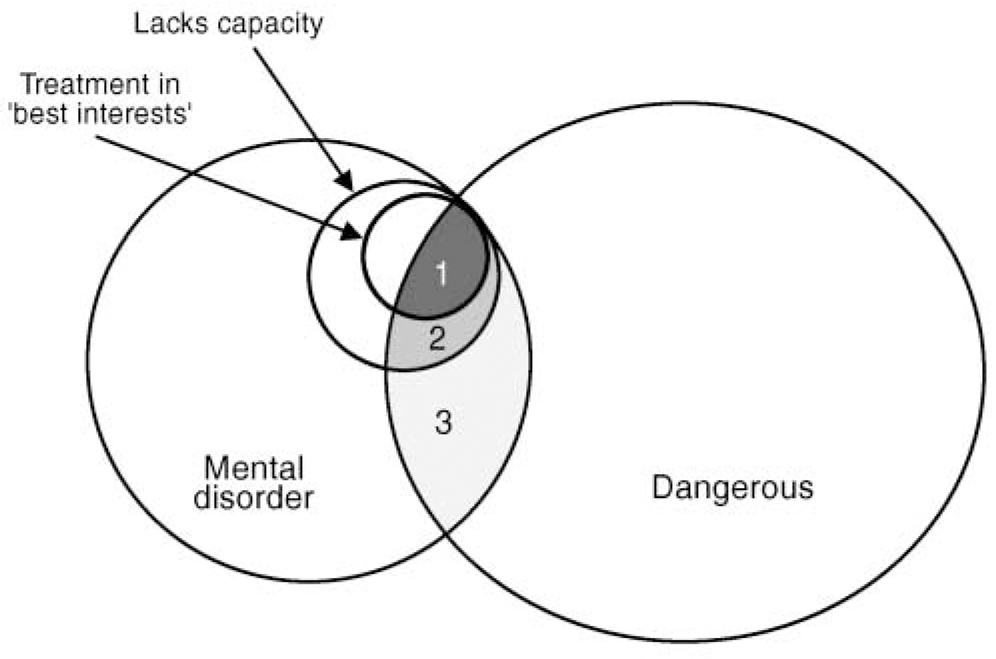

The ‘protection of others’ is a different matter. Justification for intervening in the affairs of a person for the protection of others turns on the risk of harm to others. That risk may or may not have much to do with illness, or with a patient's capacity to make treatment decisions. A diagram may help clarify some key points. Figure 1 is a representation of the possible relationships between mental disorder, lack of capacity and danger to others. The demarcation of ‘lacks capacity’ is straightforward, but some comment is required for the ‘treatment in “ best interests” ’ circle. ‘Best interests’ has no meaning for the patient with capacity, since such a person is free to choose as he or she sees fit, whether or not others regard the choice as prudent — the patient alone determines what is in his or her best interests. The occasion for a substituted ‘best interests’ judgement arises only following a loss of capacity.

Fig. 1 Overlap between mental disorder and danger to others. Patients who have a mental disorder and are assessed as dangerous fall into three groups: those in Group 1 lack capacity to make treatment decisions and treatment is in patient's best interests; those in Group 2 lack capacity to make treatment decisions, but treatment is not in patient's best interests; and those in Group 3 have capacity to make treatment decisions.

Figure 1 shows three possible classes of patient. Consider firstly Group 1. If a patient lacks capacity and treatment is in his or her best interests, involuntary treatment is justified whether the patient is dangerous or not. The latter may be significant in judging whether treatment is in the patient's best interests (by considering the consequences of violence for the patient) and might prompt particularly urgent action to ensure safety. In Group 2, the patient lacks capacity, but there is no treatment in the patient's best interests (perhaps because of non-responsiveness to all available treatments). If the patient presents a danger to others, it might be argued that this in itself could be a reason for at least containment, since causing serious harm to others will have repercussions for the patient and only make matters worse.

What about the remaining patients, those in Group 3? Let us assume that for a particular individual, dangerousness is linked to the mental disorder, and further, that some form of treatment can reduce the risk. If the patient has capacity, is danger to others an ethically acceptable reason for involuntary treatment? The Expert Committee offered a tentative ‘yes’. We argue that if involuntary treatment is imposed under these circumstances, then no health interest for the patient is being served. Protection of the public is the sole interest and such measures should find no place in a mental health act.

What justifications are offered for involuntary treatment of patients in Group 3? Perhaps the frequency or predictability of violence makes those with mental illness a singular group meriting special measures? However, the risk of violence is modestly increased in only certain groups of patients, especially in association with substance misuse (Reference Steadman, Mulvey and MonahanSteadman et al, 1998). The huge majority of violence is perpetrated by people without mental disorders (Reference Swanson, Holzer and GanjuSwanson et al, 1990). Nor is there any evidence that violence is more predictable in those with mental illness. The prediction of violence across the board is poor, and it is unlikely that it is more predictable in people with a mental disorder than in those without, for example, wife-abusers or heavy drinkers. Even if violence were more common in people with mental disorder, why should they be subjected to preventive detention and not the similarly dangerous drinker or short-tempered spouse-abuser? Some will say ‘because there is a “treatment” ’. There are at least three objections to this response. First, we have already seen that involuntary treatment can be justified only in the interests of a person's health when the person lacks capacity. Second, the argument is undetermined by the fact that those with the most treatment-resistant disorder are detained the longest. Third, dangerous persons without a mental disorder may be as, if not more, ‘treatable’. For example, the drinker who drives dangerously might respond well to ‘psychosocial interventions’ (e.g. exposure to victims, group counselling, stiff penalties) — perhaps better than most with mental disorders do to their treatments — and with a much greater reduction in harm to society.

There is another consideration. The patient with capacity, by definition, understands the consequences of refusing treatment and must thus be considered as assuming responsibility for the outcome, in the same way, for example, as we assume responsibility for the consequences of heavy drinking when intending to drive. Many potentially dangerous (non-ill) persons know that alcohol or certain provocative, but avoidable, social situations increase their risk of becoming violent. We consider them to be responsible for any unacceptable later actions, so why not the patient with capacity?

We conclude that there is no justification for singling out only those with a mental disorder for preventive detention or involuntary treatment on the grounds of public safety. If they are to be thus liable, so should the rest of us — in other words, if we are to have public safety legislation, it should be ‘generic’ and based first and foremost on the risk of harm. What we have at present, and what the Green Paper extends, discriminates against those with mental disorders: only they enter the frame for preventive action.

A further difficulty in risk prevention is the inherently poor predictability of rare events such as acts of serious violence, especially in non-forensic settings: the rarer the event the worse the prediction. The inevitability of a large, possibly huge, number of ‘false positives’ would lead to the imposition of restrictions on many persons who would not have been violent (Reference Munro and RumgayMunro & Rumgay, 2000). This applies to all risk assessment, whether the subjects have a mental illness or not.

INVOLUNTARY TREATMENT IN THE COMMUNITY

If a patient lacks capacity and treatment is in his or her best interests, the treatment need not necessarily be given in hospital. If it can be given effectively in a community setting, and this is in the patient's best health interests, there should be no bar. However, involuntary treatment should end when the patient recovers capacity; long-term non-consensual treatment is warranted only for those with enduring in-capacity. Non-consensual treatment in the community of patients with capacity for the protection of others is unjustified on any health interest basis. This is crucially important given the increasing expectations from the public that they should be protected from disturbing persons whom they see as threatening. Pressures on community mental health teams to act coercively steadily mount. Removal of the capacity criterion, while leaving a broad definition of mental disorder and the ability to ‘treat’ purely for the protection of others, leaves enormous scope for abuse.

ADVANCE STATEMENTS

The Expert Committee emphasised the value of advance directives. This follows directly from a capacity-based approach to non-consensual treatment. Presumably the ‘best interests’ of the patient are best defined by the patient when he or she is able to do so. Where capacity is predictably lost, as during a psychotic relapse, an advance directive should provide an ethically authentic statement concerning what the patient would have chosen under the circumstances (Reference Halpern and SzmuklerHalpern & Szmukler, 1997; Reference Srebnik and La FondSrebnik & La Fond, 1999).

OFFENDERS

Both the Expert Committee and especially the Green Paper are vague on mentally disordered offenders. The principles expressed by the former seem to point in the right direction. Offenders have rendered themselves liable to detention as a result of a criminal act. The public safety interest predominates and the law spells out their punishment. Offenders who have a mental illness and lack capacity, and for whom treatment is in their best interests (Group 1 in Fig. 1), warrant treatment against their objections, in a setting most appropriate to their need for care and the need for public safety. Those with mental disorders who have capacity (Group 3) and who might benefit from treatment should be offered it, but only on a voluntary basis. It should be provided in a location where it can be given effectively, taking heed of the need to ensure the safety of others. Those in Group 2 present a problem, but are fortunately likely to be few in number. They should perhaps be maintained under the most humane conditions possible consistent with both their need for care and the protection of others.

CONCLUSIONS

We have no space to consider the many practical issues raised by the Expert Committee and the Green Paper, for example, in respect of mental disorder tribunals. These are important, but if the principles are wrong, any arrangements will be unsatisfactory. ‘Capacity’ is key to revealing the assumptions underlying mental health legislation. The proper limits to involuntary treatment are more clearly delineated, and the distinction between health and public protection interests becomes obvious. The assessment of capacity is not simple. However, it is the right problem to tackle and the one consonant with the rest of medicine (Law Commission, 1995); research shows that with training and experience it can be assessed (Reference Grisso and AppelbaumGrisso & Appelbaum, 1998) and that by placing the interests of the patient centrestage it will provide the soundest safeguards against abuse.

Extensive consultation by the Expert Committee showed support for its recommendations from key stakeholders, professional and other. It rightly states “If we are to promote public safety through legislation we must endeavour to do so in a way which attracts the agreement and cooperation of the professionals who have to work within it”. The consequences of further discrimination against persons with mental disorders, as threatened in the Green Paper, will be increased stigma, an avoidance of services by vulnerable individuals who could benefit from them and consequently less public protection, rather than more.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.