To the Editor—We read with interest the article by Marquez et alReference Marquez, Jones and Whaley 1 in which the authors report an epidemiologic investigation into a Burkholderia cepacia complex outbreak among pediatric patients. This prompted a national recall of oral liquid docusateFootnote a in 2016. 2 Here, we describe a similar outbreak in our pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) from May 19, 2017 to July 30, 2017, that prompted another national product recall. 3 , 4

In May 2017, we were notified by our clinical microbiology laboratory of 3 patients in the PICU, all infants with multiple chronic medical conditions who had cultures (1 from blood and 2 from tracheal aspirates) positive for B. cepacia within the same week. A thorough review of the patients’ history, exposures and medications was conducted. Given the commonality of mechanical ventilation, we focused on possible respiratory sources of infection or exposure to previously recalled oral liquid docusate products. 2 We did not identify common respiratory medications or equipment exposures among cases and all environmental cultures were negative for B. cepacia.

As part of the outbreak investigation, bacterial isolates from cases were analyzed by the Maryland Department of Health (MDH) using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and by the Burkholderia cepacia Research Laboratory and Repository (BCRLR) at the University of Michigan using repetitive extragenic palindromic polymerase chain reaction (rep-PCR). The isolates from the 3 cases were closely related, suggesting a common exposure. The BCRLR designated this strain “1072,” which was different from the B. cepacia strain associated with the 2016 docusate outbreak.Reference Marquez, Jones and Whaley 1 Additionally, external communications revealed that 2 critically ill infants at another hospital were infected with a similar strain of B. cepacia, raising concern for a multistate outbreak.

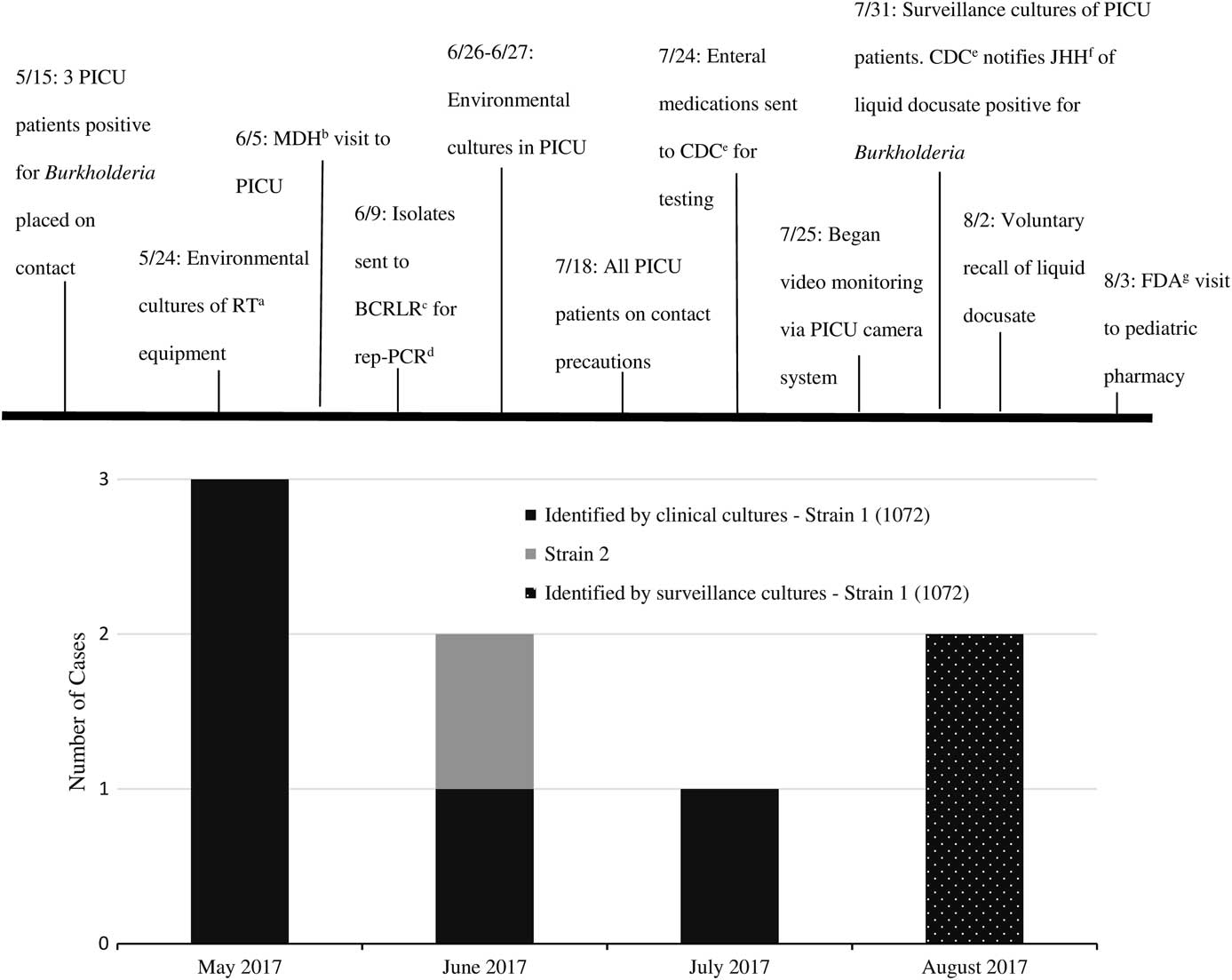

Five weeks after the initial cases, another critically ill infant with a prolonged PICU admission had a respiratory culture that grew B. cepacia strain 1072. Investigators from MDH visited our facility to review infection control practices and helped coordinate investigations among our hospital, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other hospitals with suspect Burkholderia cases. Lists of medications dispensed to all cases were compared among the affected hospitals. Two months after the initial cases, a fifth case was identified in a ventilated PICU patient whose urine culture grew B. cepacia strain 1072. Due to concerns for ongoing local transmission, universal contact precautions for all PICU patients was initiated. Our institution debuted real-time video surveillance of healthcare workers behavior with instant verbal feedback on hand hygiene compliance and adherence to standard and contact precautions. We also conducted targeted surveillance cultures. No additional respiratory cultures were positive; however, 2 stool cultures were positive for B. cepacia strain 1072. The investigation timeline is depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 Burkholderia cepacia investigation timeline. (a) Respiratory Therapy. (b) Maryland Department of Health. (c) Burkholderia cepacia Research Laboratory and Repository. (d) Repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR. (e) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (f) Johns Hopkins Hospital. (g) U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

A CDC epidemiologist noted that the National Drug Code (NDC) for oral liquid docusate from the manufacturer associated with the 2016 docusate outbreak (NDC 0536-0590-85) appeared in medication administration data for case patients at another hospital, and an infection preventionist at our hospital determined that docusate with this NDC had also been administered to case patients at our hospital.Reference Marquez, Jones and Whaley 1 Based on this finding, we provided opened and unopened bottles of docusate to the CDC and US Food and Drug Administration for culture. In late July, we were informed that an open bottle of liquid docusate grew B. cepacia, after which all docusate products from the implicated manufacturer were removed from our patient care areas and pharmacies. Burkholderia cepacia isolated from the opened docusate bottle was confirmed as strain 1072, implicating the contaminated oral liquid docusate as the likely common source of infections at the hospitals with affected patients. In early August, there was a voluntary recall of liquid docusate due to contamination concerns 3 and later that week, a broader recall of additional liquid medications took place. 4 , 5

Respiratory and bloodstream infections after exposure to an enteral medication are somewhat unexpected. We speculate that B. cepacia might have colonized and infected infants via aspiration of enteral fluids, translocation across the enteric mucosa or migration into the genitourinary tract from the gastrointestinal tract, putting the most critically ill patients at highest risk.Reference Marquez, Jones and Whaley 1

We learned several unique lessons from this experience: (1) Identification of respiratory sites of infection should not limit investigation to only respiratory-related sources. (2) Despite early identification of a bacterial strain different from that implicated in previously recalled products, outbreak investigators should maintain a high level of suspicion and use NDC codes to identify common products or manufacturers. (3) Rapid reporting to and involvement of federal, state and local agencies in outbreak investigations can help identify a common exposure and support identification of pathogenic bacteria in medications and other products. In addition, access to a national reference laboratory for molecular typing was invaluable in this investigation and outbreak confirmation. (4) While there are no national guidelines on disclosure to patients and families in outbreak investigations, clinicians should provide clear and effective communication.Reference Daugherty Biddison, Berkowitz and Courtney 6 Throughout this investigation, we strived to be transparent with patients’ families. We personally spoke with the families of the affected patients and provided all families in the PICU with an informational handout, which was well received.

Lastly, while some B. cepacia outbreaks have never been linked to a known source,Reference Siddiqui, Mulligan and Mahenthiralingam 7 B. cepacia has relatively low occurrence in non-cystic fibrosis patients. Therefore, identification of a cluster of infections, particularly those caused by an identical strain, should raise suspicion for possible product contamination or infection control deficiencies, and should prompt further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Mary-Beth Griffith, LeAnn McNamara, Matt Crist, Janet Glowicz, Pam Dodge, Stacey Mann, Alice Hsu, Mark Romagnoli, Roshni Mathew, the Division of Medical Microbiology, the Department of Pharmacy, the Department of Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control, Maryland Department of Health Laboratories administration, and the entire Johns Hopkins Hospital PICU staff for their dedication to patient safety and helping to quickly contain this outbreak.

Financial support: No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Potential conflicts of interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.