Enamel as a prestige medium

In the tenth and eleventh centuries, cloisonné enamel served an important symbolic role in promoting the prestige of the Byzantine court. Enamel was used to adorn the emperor and the furnishings that surrounded him as well as to impress Byzantium's neighbours.Footnote 1 In 1045/6, the Fatimid Caliph al-Mustanṣir bi-Allāh received a lavish gift from Constantine IX Monomachos that included one hundred ‘gold vessels of various kinds inlaid with enamel’.Footnote 2 In the medieval West, gifts of Byzantine enamel might not only provoke wonder at the skill of their manufacture, but might also encode more explicit messages of Byzantine superiority.Footnote 3 On the Holy Crown of Hungary, for example, one can see the almost diagrammatic parallel between Christ flanked by the archangels Michael and Gabriel on the front of the crown and the plaques on the opposite side of the crown showing Michael VII Doukas flanked by his son Constantine and Géza I of Hungary (Fig. 1).Footnote 4 Multiple criteria—position, pose, regalia, and colour of the identifying inscriptions—combine with the virtuosity of the enamel work to drive home the message of Byzantine superiority.Footnote 5 By bearing the imperial image, the enamel crown conveyed the implicit idea of the recipient's subordination into a universal political hierarchy under the sway of the emperor in Constantinople.

Fig. 1. Holy Crown of Hungary, front and back, with Byzantine enamels of c. 1075, Hungarian National Parliament Building, Budapest. Photography © Hungarian Pictures / Károly Szelényi.

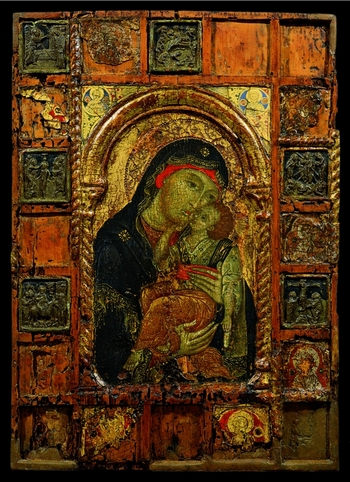

Byzantine cloisonné enamel continued to command admiration long after the disaster of 1204. During his stop in Venice in 1438, the Byzantine legate to the Council of Ferrara-Florence, Sylvester Syropoulos, viewed the Pala d'Oro and admired ‘the radiance of the material’ (λαμπρότητι τῆς ὕλης) of the many holy images (θείας εἰκονογραφίας) incorporated into it. He recognized also the imperial portraits (στηλογραφίας) and traced their origin—rightly or wrongly—to the Constantinopolitan monastery of Christ Pantokrator.Footnote 6 Along with precious gemstones (for which enamel was itself in some sense a substitute), Byzantine enamels seem to have remained a prized possession and a potential medium of exchange in the fourteenth century.Footnote 7 Actual evidence of the production of cloisonné enamel in fourteenth-century Constantinople, however, is elusive. Production seems to have continued for only a few decades after 1204. There survive three sets of cloisonné enamel plaques that can be plausibly dated to this period: one set adorning a book cover in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice,Footnote 8 another applied to the frame of an icon of the Virgin at Freising, near Munich,Footnote 9 and the third group on an episcopal mitre now in Stockholm.Footnote 10 After the middle of the thirteenth century little—if any—true cloisonné enamel was produced in Byzantium.Footnote 11 Although sets of figural cloisonné medallions were used to ornament the frames of icons, as with the icon of the Virgin in Freising, when they appear in Palaiologan settings, such enamels were presumably reused from earlier objects. For instance, the set of cloisonné medallions on the frame of a fourteenth-century mosaic icon of St. John the Theologian at the Great Lavra can be demonstrated to come from an earlier icon of John the Forerunner.Footnote 12

The glass flux used by the Byzantines for translucent enamel had a melting point of about 1000 °C, and thus gold, which remains solid well beyond that temperature, was the preferred metal for the technique.Footnote 13 By the end of the thirteenth century, however, the imperial treasury was chronically short of gold bullion, so much so that the co-emperor Michael IX had to resort to melting down household gold and silver wares for coin to raise an army in 1304.Footnote 14 The civil wars of the fourteenth century only exacerbated the already existing shortage. Numismatic evidence points to a steady decline in the gold content of the hyperpyron over the reigns of Michael VIII and Andronikos II, and the millennium-long tradition of Byzantine gold coinage reached its end with the reign of John VI Kantakouzenos.Footnote 15 Given the financial straits of the empire in its final centuries, it must have been difficult to acquire sufficient gold to sustain (or revive) the regular production of translucent cloisonné enamels.Footnote 16 One possible solution was to switch to silver as the supporting metal, using a limited palette of opaque enamels with relatively low melting points. The fourteenth-century silver frame of the Mandylion icon in Genoa (recorded there by 1388) uses a combination of opaque enamel and niello set in the concavities of figures worked in repoussé. This technique has been interpreted by Paul Hetherington as a one-off solution by an artist otherwise unfamiliar with working in enamel.Footnote 17 These narrative scenes framing the Genoa Mandylion are the sole group of figural enamels that can be securely attributed to a fourteenth-century Byzantine artist. Although fine basse taille enamels on silver ornament a number of objects produced for Byzantine patrons, such as the chalice and paten of Thomas Komnenos Prelubović, Despot of Ioannina (1367-1384), it is likely that these commissions were carried out by Venetian artists.Footnote 18 Far more typical of late Byzantine production is the rather dull green pseudo-champlevé enamel seen on the handle of a copper censer (katzion) preserved in the Benaki Museum.Footnote 19 Green or blue-green enamel was also used occasionally to ornament the repoussé frames and revetments of Palaiologan icons.Footnote 20 The Freising icon of the Virgin, which carries on its frame the series of thirteenth-century cloisonné roundels already mentioned, also received a silver-gilt revetment towards the end of the fourteenth century. This seems to have formed part of a renovation to fit the icon as a suitable gift for Manuel II's fund-raising journey through Western Europe, during which he presented it to Giangaleazzo Visconti of Milan.Footnote 21 The revetment's inscriptions resemble enamel, but according to an analysis by David Buckton, they actually contain pigment in an organic binding medium rather than glass flux.Footnote 22 Given that these additions to the icon were likely part of an imperial commission, one imagines that proper enamel would have been used if it had been at all feasible. Rather than shifting their attention to other art forms, Byzantine artists and patrons seem to have sought ways to compensate for the loss of the necessary materials and skills for the manufacture of cloisonné enamel. In other words, the Palaiologan period witnessed an attempt to keep up appearances, extending the life of a prestige medium by other means.

Pseudo-Kodinos and the Skaranikon

The ceremonial manual on the offices of the Byzantine court, long known under the name of Pseudo-Kodinos, describes the use of luxury media at the highest levels of the Palaiologan court. The testimony of Pseudo-Kodinos is especially interesting in that he treats not only costume and regalia, but also the imperial image which is systematically deployed on the headgear known as the skaranikon. His treatise thus establishes a relationship between the imperial likeness as a sign of office and rank in court ceremonial and the artistic media in which that image was fashioned. The text not only gives an insight into hierarchy of media in the Palaiologan period, but also a sense of the place of ersatz techniques within this system.

The composition of the text of Pseudo-Kodinos’ treatise is dated by Verpeaux on internal evidence to the reign of John VI Kantakouzenos, who is alluded to at several points in the text, or to the reign of his successor, John V Palaiologos.Footnote 23 The most recent research on the treatise has confirmed Verpeaux's dating (shortly after 1347, but incorporating some earlier material) and underlined the connections between certain features of the text and John VI's reign.Footnote 24 The treatise differs from several other fourteenth-century lists of precedence in the ordering of the ranks of the first seven offices.Footnote 25 Since the discussion here concerns the internal logic of Pseudo-Kodinos’ costume system, the ordering of the ranks will follow his numbering, in which the first seven ranks after the emperor are (1) despotes, (2) sebastokrator, (3) caesar, (4) megas domestikos, (5) panhypersebastos, (6) protovestiarios, and (7) megas doux. Footnote 26

The treatise explicates in order of rank the regalia associated with each office. On the occasions of greatest solemnity, the higher officials of the court wore a silk kabbadion—a long-sleeved, full-length garment fastening down the length of the front and derived, as its name implies, from the kaftans of the Turkic world.Footnote 27 Along with the kabbadion, the most important article of dress of the courtier was his feast-day headgear, the skaranikon. Footnote 28 Shoes of appropriate colour to the rank of the wearer, along with rods of various sorts held in the hand, completed the ensemble.Footnote 29 These descriptions and their parallels in the visual arts paint a vivid picture of a court clothed in silk and gold. The impression of precise order and courtly luxury given by the enumeration of these insignia stands in stark relief, however, against the background of social upheaval and economic deprivation occasioned by the civil wars of the fourteenth century. The famous passage from Nikephoros Gregoras on the coronation of John VI Kantakouzenos at the palace of Blachernai in 1347 records the substitutions of gilded ceramic for precious metal banqueting vessels and of glass pastes for the crown jewels of the empire, which had been pawned by Anna of Savoy in 1343 and never redeemed.Footnote 30 Even Pseudo-Kodinos’ own account is a witness to the scarcity of precious metals. At the imperial coronations, the emperor is said to distribute small bags of coins, apokombia, to the assembled crowd, who presumably take them away.Footnote 31 On the other hand, at the annual largitio ceremony of Christmas Eve, the megas domestikos distributes plates of silver and gold to the assembled courtiers, but everyone apart from the megas domestikos himself is expected to give them back to the imperial treasury at the end of the ceremony.Footnote 32 The ceremonial distribution of ‘gifts’ that are immediately returned suggests the limits of imperial wealth.Footnote 33 Despite the impression of courtly magnificence and order in Pseudo-Kodinos, one must bear in mind the background of material poverty against which he was writing.Footnote 34

One might almost see Pseudo-Kodinos’ meticulous delineation of the ceremonial dress of the court as a reactive emphasis on taxis over against the economic decline and political disorder that followed the second civil war. Under Andronikos III, according to the scandalized Nikephoros Gregoras, the court had presented a kind of sartorial free-for-all, with courtiers, regardless of their seniority, wearing headgear ‘of many and diverse kinds and unusual forms according to the will of each.’Footnote 35 Gregoras interpreted this disorder in dress as a precursor to the disastrous conflicts that would follow Andronikos III's death. The vestimentary system laid out in Pseudo-Kodinos puts aside such frivolity in favour of a precise correlation between each dignity and its insignia. Every rank has two hats, generally the skiadion and skaranikon, of prescribed materials and decoration. The skaranikon of each rank is carefully defined as to five criteria: its overall material, its colour, the presence or absence of an imperial portrait, the pose of the imperial figure, and finally, the medium in which those images are executed. Three basic types of skaranikon are described in the text. The most elite version, pertaining to the despotes, was of goldsmith's work (χρυσοχοϊκόν), decorated with gems and pearls, as seen on the fragmentary portrait of the despot Theodore I Palaiologos at the Aphendiko in Mistra (Fig. 2).Footnote 36 From the megas domestikos (rank 4) to the protoierakarios (rank 48), the skaranikon is of silk ornamented with gold embroidery over its surface. Finally, from the rank of megas diermeneutes (50) to the papias (80), the skaranikon is of red napped fabric (χάσδεον) without embroidered decoration.Footnote 37

Fig. 2. Despot Theodore I Palaiologos, fresco, late 14th century, Aphendiko, Mistra. Drawing after J. Ebersolt, Les arts somptuaires de Byzance: étude sur l'art impérial de Constantinople (Paris 1923) 125, fig. 58.

Colour, furthermore, is used systematically to differentiate groups among the wearers of the silk skaranika (rather confusingly referred to as ‘gold skaranika’ by Pseudo-Kodinos).Footnote 38 Red-and-gold (χρυσοκόκκινον) silk with gold embroidery (συρματέϊνα) covers the skaranika of the ranks from the megas domestikos (4) to the megas stratopedarches (10), while the ranks from the megas primmikerios (11) to the parakoimomenos tou koitonos (17), wear a skaranikon of apricot-coloured (βερικοκκόχροον) silk with gold embroidery.Footnote 39 The colour changes again with the logothetes tou genikou (18) through the eparchos (23), who wear gold-and-white (χρυσάσπρον) skaranika with embroidered decoration.Footnote 40 Finally, yellow-and-gold (χρυσοκίτρινον) with gold embroidery marks the skaranikon of the megas droungarios tes vigles (24) through the protoierakarios (48).Footnote 41 Whereas the Komnenoi used colour as a mark of rank for the new dignities created or revamped for members of the imperial family, the Palaiologan period marks the first systematic extension of the concept to embrace nearly the whole of the court and its dress.Footnote 42 One sees an analogous but not identical system of colour in the prefatory miniatures added c. 1330 to the Lincoln College Typikon. Footnote 43 Each of the men of the court is shown wearing the kabbadion and a skaranikon with the imperial portrait.Footnote 44 The colour of the kabbadion—red, green, or apricot—varies with their rank, whereas the skaranikon is identical for all the figures that wear it (Fig. 3).Footnote 45 The inverse is true in the text of Pseudo-Kodinos: while the skaranikon varies in colour according to the wearer's rank, only the highest officials are assigned a designated colour of kabbadion,Footnote 46 while the other courtiers from the megas doux (7) to the parakoimomenos tou koitonos (17) are allowed to choose their kabbadion from any of the customary silks (βλάτιον οἷον ἄν βούλοιτο ἀπὸ τῶν συνήθων.).Footnote 47 With the kabbadion as such an ambiguous signifier in the manual, the headgear assumes far greater importance as a mark of rank.

Fig. 3. Megas Stratopedarches John Synadenos and Theodora Palaiologina, Typikon of the Nunnery of Bebaia Elpis, Lincoln College, Oxford, MS Gr 35, fol. 2r. Photograph © Lincoln College, Oxford, 2017.

The imperial portrait, a feature of the thirty-seven highest ranks (excluding the despotes, sebastokrator, and caesar), is the most striking means of displaying hierarchy among the wearers of the ‘gold skaranika’. The pose of the portraits varies according to rank: a standing image of the emperor, flanked by images of angels, appears on both the front and back of the skaranikon of the megas domestikos (4), panhypersebastos (5), and protovestiarios (6).Footnote 48 The skaranika of the megas doux (7) through the eparchos (23) lack the angels, but have the images of the emperor standing in front and enthroned behind.Footnote 49 From the megas droungarios tes vigles (24) down to the protoierakarios (48), the skaranikon shows the emperor seated on an elevated throne on the front and on horseback behind.Footnote 50 These portrait types show a gradation from the emperor's most deferential pose—standing, as he would be seen if depicted in the company of Christ or the angels—to his most imposing postures, enthroned or seated on horseback.Footnote 51 In other words, the emperor's image becomes increasingly imposing in inverse proportion to the dignity of its wearer.Footnote 52 A tabular presentation Pseudo-Kodinos’ information on the headgear makes clear that some of the shifts in pose coincide with the changes in the colour of the hat's fabric and in the medium of the portraits, while others do not (Table 1).

Table 1. The ‘gold skaranika’ according to Pseudo-Kodinos

aNote that for ranks 27, 28, 30, 39, 40, 44, 47, and 49, Pseudo-Kodinos prescribes a turban (phakeolis) rather than skaranikon on feast days.

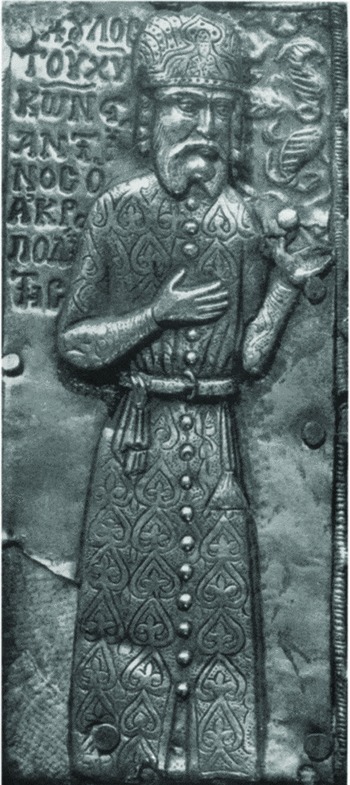

Unfortunately, it is impossible to parallel this hierarchy of poses in any surviving images of courtiers’ skaranika. No known work of art depicts a skaranikon with the standing imperial figure stipulated for ranks 4 to 23. The hats shown in the Lincoln College Typikon uniformly display an enthroned emperor. The donor portrait of Constantine Akropolites on the silver-gilt repoussé frame of an icon of the Hodegetria in Moscow, among the earliest representations of the skaranikon with the imperial portrait, shows a bust-length imperial portrait, which is not among the poses listed by Pseudo-Kodinos (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).Footnote 53 Unfortunately, Constantine is labelled by his inscription only as ὁ δοῦλος τοῦ Χριστοῦ, so we cannot be certain what office he held at the time of the icon's manufacture around 1300.Footnote 54 Roughly contemporaneous with the portraits in the Lincoln College Typikon is the image of the megas doux Alexios Apokaukos in the frontispiece of the Hippocrates manuscript in Paris (Fig. 6).Footnote 55 Dating between his elevation to the office in 1331 and his assassination in 1345, the portrait shows him wearing a skaranikon with a slightly bulbous crown of red material. The enthroned emperor shown on the front of the hat is framed under a pearl-edged trefoil arch. Pseudo-Kodinos stipulates such pearl embroidery only for the skaranikon of the megas domestikos (rank 4)—but in this case it is to frame a standing (not enthroned) portrait of the emperor, flanked by angels in roundels.Footnote 56

Fig. 4. Icon of the Hodegetria with silver repoussé frame showing Constantine Akropolites and his wife Maria as donors, end of 13th or beginning of 14th century, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Photograph copyright The State Tretyakov Gallery.

Fig. 5. Constantine Akropolites, detail of silver repoussé icon frame. Photograph after A. V. Bank, Byzantine Art in the Collections of Soviet Museums (Leningrad, 1977), fig. 245.

Fig. 6. Alexios Apokaukos, Paris Bibliothèque Nationale ms. Gr. 2144, fol. 11r. Photograph: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Finally, Pseudo-Kodinos specifies the medium of the imperial portrait, which varies, like the colour and quality of the skaranikon, according to the rank of the wearer. This is the most critical and intriguing aspect of his list. If one makes the assumption that the more esteemed materials and techniques were used for the higher ranks of courtiers, then one can use the costume list of Pseudo-Kodinos to reconstruct a partial hierarchy of media for the Late Byzantine era. For those who wear the red-and-gold skaranika, that is, courtiers of rank (4) through (10), the image is described as ἰνοκοπητός, a word Verpeaux glosses as ‘finement ciselé.’Footnote 57 The word is rare, but it appears (spelled οἰνοκωπητός) in the inventory of Hagia Sophia from 1396. There it describes decoration on metalwork: patens, chalices, and the like, frequently with figural imagery.Footnote 58 Given the context, it seems most likely that repoussé metalwork is described.Footnote 59 Repoussé as a decorative technique seems to have flourished particularly in the thirteenth and fourteenth century, perhaps in part filling a void created by the decline of cloisonné enamel. The Monastery of Xeropotamou on Mount Athos preserves the will of Theodore Skaranos, dated to c. 1270–1274, which mentions an icon revetment in the technique;Footnote 60 numerous comparable examples survive, such as the repoussé icon frame with the image of Constantine Akropolites wearing the skaranikon. An epigram of Manuel Philes, no doubt intended for inscription on the object it describes, praises a silver panagiarion for the blessing of bread in honour of the Virgin, with an «ἰνοκοπητόν» image of the Mother of God at its centre.Footnote 61 Although Pseudo-Kodinos’ text does not specify the metal, the parallel descriptions in the Hagia Sophia inventory and in surviving works suggest that gilded silver would have been the material from which the imperial portraits were formed. While the pearls and the angels they encircle drop out of the picture below the rank of protovestiarios, the ἰνοκοπητá portraits appear on the headgear down to the megas stratopedarches, the tenth in order of rank. The change in the pose of the portraits and the elimination of the flanking angels corresponds with the transition from the highest ranks of officials, those with a ‘signature’ colour marking their mantles and shoes as well as their documents, to those ranks without this distinction.Footnote 62 If the identification of «ἰνοκοπητός» with the technique of repousée is correct, its prestige in the Palaiologan period is attested by its use—in pure gold—for a reliquary of the true cross preserved in Siena. In the more common medium of silver-gilt, it adorned a number of other prestigious reliquaries created in the early fourteenth century.Footnote 63 It is thus a logical medium for use on the headgear of the more senior ranks of courtiers.

The lower-ranked half of the courtiers who wear the skaranikon with the imperial image wear headgear with the portrait embroidered in gold (or silver-gilt) wire (χρυσοκλαδαρικὸν συρματέϊνον). This group has at its head the megas droungarios tes vigles (rank 24), whose skaranikon ‘is made of gold-yellow silk and is embroidered with gold wire. It has at the front an image of the emperor seated on an elevated golden throne and at the back the emperor on horseback.’Footnote 64 The same headgear is worn by the courtiers down to rank 48, the protoierakarios.Footnote 65 Numerous examples of ecclesiastical insignia with gold embroidery that survive from fourteenth-century Byzantium make it possible to envision what such portraits might have looked like.Footnote 66 Because of the relatively high purity of silver needed to draw wires suitable for embroidery, the συρματέϊνος portraits must have been somewhat costly to produce.

While there is relatively little difficulty in interpreting the medium of the gilded repoussé imperial figures on the skaranika of ranks 4–10 or the gold-embroidered imperial figures worn by ranks 24–48, the imperial portrait worn by the officials of intermediate rank presents a thornier problem. They are described as having skaranika with the imperial image «ὑπὸ ὑελίου λεγομένου διαγελάστου.»Footnote 67 The first part of this formula is simpler to interpret. In certain late Byzantine contexts, ὑέλιον seems to indicate enamel. As Paul Hetherington has demonstrated, the normal middle-Byzantine Greek words for enamel, χύμευσις, and for enamelled work, χειμευτός, all but disappear from texts written after 1204, while the word ὑέλιον frequently occurs in contexts that suggest that it served as a lexical replacement.Footnote 68 As late as 1200, the inventory of the treasury of the Monastery of St. John on Patmos could precisely describe the ornaments of the icon of John the Theologian as χρυσοχειμευτῶν–enamelled on gold.Footnote 69 But in 1438, when Sylvester Syropoulos visited Venice and claimed that the various holy images (θείας εἰκονογραφίας) making up the Pala d'Oro were taken from Constantinople, he seemingly had no word to describe their medium (ὕλη).Footnote 70 The inventory taken of the treasury of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople in 1399 lists several liturgical vestments and vessels adorned with ὑέλια, which would seem to be enamels, and others with λιθάρια ὑελία, which could be interpreted as glass paste gems, as Paul Hetherington has suggested.Footnote 71

If, based on other late-Byzantine texts, we interpret ὑέλιον in this context to mean enamel, what does the text mean by further specifying that they are called διαγέλαστος? The «λεγομένου» of the phrase «ὑπὸ ὑελίου λεγομένου διαγελάστου»Footnote 72 seems to suggest apology for the introduction of a colloquialism. The term appears a further time in the text, where it describes the imperial image on the skaranikon of the logothetes tou genikou, «τοῦ βασιλέως εἰκόνα διαγέλαστον».Footnote 73 These two uses of the word in Pseudo-Kodinos are its only known instances in the late-Byzantine period, and in this context it has traditionally been glossed as signifying transparency.Footnote 74 Du Cange, citing this passage from De Officiis as his sole reference, interprets διαγέλαστος as ‘sub vitri specie pellucidi’,Footnote 75 and the Lexikon zur byzantinischen Gräzität similarly translates διαγέλαστος in this instance as durchscheinend (albeit with a query).Footnote 76 These translations, however, do not seem adequate to explain its specific use in this passage and its relation to the imperial portrait. The word itself comes from γελάω, to smile or laugh at something, and the sense of transparency could be argued from its application to smiling weather or smiling seas.Footnote 77 On the other hand, the lexicon of pseudo-Zonaras makes plain that the word and those formed from it preserved its primary sense of mockery into the middle-Byzantine period.Footnote 78 Homer's phrase ἔργα γελαστά, describing the ‘laughable affair’ of Aphrodite and Ares caught in the net of Hephaistos, is glossed by Eustathios of Thessalonike, who connects it to the verbal forms γελῶ and γελάζω.Footnote 79 The tenth-century bishop Leo of Synada uses the same term, γελαστός, to ridicule a bureaucratic underling who has written to him with inadequate deference as ‘more of a joke than a joker.’Footnote 80 The only text apart from Pseudo-Kodinos to use the form διαγέλαστος (-ον), the sixth-century (and much reworked) life of St. Symeon Stylites the Younger, uses it in two places to designate an object of ridicule: in one instance a fearsome beast that is defeated and publicly paraded by the saint so that it becomes a laughingstock (διαγέλαστον γέγονος), in the other a man suffering from alopecia, who is derided by his neighbours (διαγέλαστος καὶ ἐξουθενημένος ὑπὸ πάντων).Footnote 81 Assuming some continuity of its meaning, how should we account for such a word in an utterly serious work on court ceremonial?

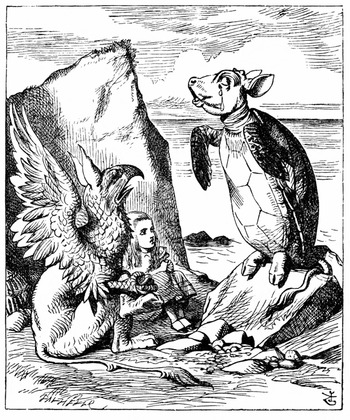

Both modern editions of Pseudo-Kodinos accept that the image being described by the phrase ὑπὸ ὑελίου λεγομένου διαγελάστου is some kind of painted image under glass, but parallel usages suggest διαγέλαστος must mean something other than ‘transparent’. Within the semantic field suggested in other contexts, ‘an object of mockery’, I would propose a further refinement, translating διαγέλαστος as ‘mock’ in the sense of ‘mock turtle soup.’ In pursuing this rendering, my intention is to grasp at hints that the author of Pseudo-Kodinos’ treatise was aware that the technique was a substitute for another, more valuable one. Mock turtle soup was an economizing response to the shortage and expense of real sea turtles after decades of their decimation for the dining tables of Europe. Lewis Carroll's Mock Turtle, with the head and tail of a calf, of course alludes to the main ingredients of mock turtle soup (Fig. 7).Footnote 82 The other notable attribute of Carroll's character is his continuous weeping. When Alice asks the Mock Turtle about his tears, he explains to her that he is mourning his youth, when he was a real turtle.Footnote 83 The poignancy of the ersatz brings us back to Nikephoros Gregoras, who records his dismay at the poverty into which the Byzantine Empire had fallen by the time of John VI and his coronation with gems of glass paste:

The palace was so poor that there was in it no cup or goblet of gold or silver; some were of pewter, all the rest of clay. . . most of the imperial diadems and garb showed only the semblance of gold and jewels;. . . they were of leather and were but gilded. . . or of glass which reflected in different colors; only seldom, here and there, were precious stones having a genuine charm and the brilliance of pearls. . . To such a degree the ancient prosperity and brilliance of the Roman Empire had fallen, entirely gone out and perished, that, not without shame, I tell you this story.Footnote 84

Fig. 7. John Tenniel, Alice with the Mock Turtle and Gryphon, illustration from Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, (London, 1866), 141.

Gregoras’ passage in turn served as inspiration for Constantine Cavafy's twentieth-century poem ‘Of Coloured Glass’ (Ἀπό ὑαλί χρωματιστό), in which he described the use of these substitute materials as:

σάν μιά διαμαρτυρία θλιβερή

κατά τῆς ἄδικης κακομοιριᾶς τῶν στεφομένων.

Εἶναι τά σύμβολα τοῦ τί ἥρμοζε νά ἔχουν,

τοῦ τί ἐξ ἅπαντος ἦταν ὀρθόν νά ἔχουν

στήν στέψι των ἕνας Κύρ Ἰωάννης Καντακουζηνός,

μιά Κυρία Εἰρήνη Ἀνδρονίκου Ἀσάν.

a sad protest against

the unjust misfortune of the couple being crowned,

symbols of what they deserved to have,

of what surely it was right that they should have

at their coronation—a Lord John Kantakuzinos,

a Lady Irini, daughter of Andronikos Asan.Footnote 85

Cavafy, in fact, inverts the shame expressed by Gregoras, seeing the use of the ersatz rather as an insistence on the dignity proper to the imperial office and the nobility of its occupants, even in a time of political and economic collapse. The agenda of Pseudo-Kodinos’ treatise aligns with Cavafy's view: the good order of imperial ceremonial and the use of techniques that resemble the court's traditional luxury goods help to keep up the appearance of imperial taxis despite constricted means. An important clue to this is the position of the imperial image ὑπὸ ὑελίου διαγελάστου in the hierarchy of skaranika: it belongs to ranks lower than the previous-metal repoussé images, but to ranks higher than those with the gold-embroidered images. The portraits in verre églomisé thus rank lower than one would expect for the true cloisonné enamels that they evoke, but higher than images in the (almost certainly) more costly medium of gold embroidery.

The question remains, of course, whether such a mode of thinking about substitute materials and techniques is purely modern, or whether it is supported by evidence from the Palaiologan era. In fact, while evidence of an analogous attitude in the late Byzantine period is scarce, it does exist. One of the fourteenth-century repoussé reliquaries preserved in Siena, containing a relic of St. John Chrysostom, bears an inscription that plays off the saint's epithet to reveal awareness of its own material:

ὄλβιον χρυσοῦν λείψανον Χρυσοστόμου

ἐν ἀργύρῳ κρύπτεται τῷ διαχρύσ[ῷ]

That is to say, ‘The blessed golden relic of Chrysostom is hidden in gilded silver.’Footnote 86 The way the text is placed on the object—wrapping inconspicuously around the sides of the reliquary—simultaneously hides and advertises the object's real material. Gilded silver, of course, co-existed with gold throughout the Byzantine period, and the two were frequently used interchangeably. One might cite the two staurothekai of Irene Doukaina and her daughter, both from the early twelfth century, the mother's reliquary silver-gilt, the daughter's of gold.Footnote 87 What seems to be new in the Palaiologan period is the awareness and acknowledgement of the material as something other than what it appears to be.

One might also compare the rather battered icon of the Virgin Eleousa in the Benaki Museum, Athens, which has been attributed to a Byzantine artist perhaps working in fourteenth-century Venice (Fig. 8).Footnote 88 On either side of the arch framing the image are roundels showing the Evangelists Luke and Matthew (Fig. 9). Although the bright colours and gold resemble enamel, the shattered glass immediately betrays the fact that they are, in fact, executed in the cheaper medium of verre églomisé. The icon is framed by panels of moulded and painted stucco, imitating carved steatite. These, in turn, alternate with busts of saints, which again imitate enamel—or even, perhaps, imitate verre églomisé substitutes for enamel—but are in fact merely tempera painted on a gilded gesso ground.Footnote 89 The use of so many fictive media in this case seems to be conscious and deliberate, although only our textual sources can point us towards the attitude with which the ersatz was approached in late Byzantium. The same awareness of sleight of hand—evidenced both in Gregoras and by the anonymous author of the epigram on the Chrysostom reliquary—can be discerned in Pseudo-Kodinos’ use of the term διαγέλαστος.

Fig. 8. Icon of the Virgin Eleousa, 14th century, Benaki Museum, Athens. Photograph © 2017 by Benaki Museum Athens.

Fig. 9. Icon of the Virgin Eleousa, detail of verre églomisé image of St. Matthew. Photograph © 2017 by Benaki Museum Athens.

In the midst of describing the skaranikon appropriate to each rank, Pseudo-Kodinos indulges in a remarkable digression on its ancient genealogy. He describes its transmission from the Assyrians to the Persians through the conquests of Cyrus, and thence through Alexander the Great to the Roman Empire, whence it passed by descent to the Byzantine emperors.Footnote 90 While Pseudo-Kodinos’ account of the origins of the skaranikon is clearly spurious, its superficial resemblance to the so-called korymbos, the bulbous form that adorns the crown worn by certain Sasanian rulers, may have suggested to an observant eye an origin in the ancient Near East.Footnote 91 As Maria Parani has pointed out, this imaginative grafting of the then-recently codified headgear of the ‘Romans’ onto the root stock of the ancient empires of the East situates the fourteenth-century order the more firmly in the divinely ordained flow of history.Footnote 92 It is striking, however, that this emphasis placed by Pseudo-Kodinos on an (invented) historical lineage is coupled with a clear awareness of the extent of the changes in court ritual. Far from attempting to gloss-over discontinuities, the author goes out of his way to highlight such ruptures, often using πάλαι, ‘of old’, or πρότερον, ‘formerly’, to signal differences between past practice and the fourteenth-century present.Footnote 93 This tension between emphasis on the longue durée and on the changing vicissitudes of the empire is highlighted in other ways in the text, notably in Pseudo-Kodinos’ discussion of the symbolism of the emperor's own insignia:

By carrying the cross the emperor shows his faith in Christ. . . by his black sakkos, the mystery of the imperial office; by the earth which, as we said, is called akakia, that he is humble, as he is mortal, and that he is not to be proud or arrogant because the imperial office is so exalted; by the handkerchief, the inconstancy of his office and that it passes from one person to another; by the sword, authority.Footnote 94

Far from asserting an invincible and immutable imperial power, Pseudo-Kodinos emphasizes the unpredictability of imperial succession. One can see in this a kind of microcosmic view of the same attitude writ large in the excursus on the skaranikon. The decoration of the hat may economize, but its form lays claim to a legacy of greatness. By placing what was in fact a rather recent version of court headgear within a genealogy of empires, Pseudo-Kodinos foregrounds the essential tension between the grand ideological claims of the empire's central place in history and its vastly reduced state in the mid-fourteenth century.

Given the particular role the skaranikon plays in the text in situating the emperor and his retinue in this historical sequence of hegemonic powers, it is significant that the images of the emperor are not merely said to be in painted glass, but rather ‘mock enamel’, reflecting an awareness of what the material ought to have been under better circumstances. The medium of verre églomisé is thus more than merely a stopgap measure; it is rather an assertion of continuity with the empire's past era of hegemony. If this reading is correct, the attitude towards the ersatz expressed in Pseudo-Kodinos is in fact closer to that of Cavafy's poem than it is to the open lamentation of Gregoras: the substitute medium of painted glass is not so much meant to deceive, as to stand as ‘symbols of what they deserved to have.’