Introduction

As of the end of 2022, there were approximately 0.73 billion confirmed cases of COVID-19, resulting in more than 6 million deaths worldwide (World Health Organization, 2022). The unpredictability and uncertainty of the pandemic itself, along with the policy restrictions and economic recession, may have caused great mental health consequences amongst the global population (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Barnett, Greenburgh, Pemovska, Stefanidou, Lyons, Ikhtabi, Talwar, Francis, Harris, Shah, Machin, Jeffreys, Mitchell, Lynch, Foye, Schlief, Appleton, Saunders, Baldwin, Allan, Sheridan-Rains, Kharboutly, Kular, Goldblatt, Stewart, Kirkbride, Lloyd-Evans and Johnson2023; Aknin et al., Reference Aknin, De Neve, Dunn, Fancourt, Goldberg, Helliwell, Jones, Karam, Layard, Lyubomirsky, Rzepa, Saxena, Thornton, VanderWeele, Whillans, Zaki, Karadag and Ben Amor2022; Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Wykes, Galderisi, Nordentoft, Crossley, Jones, Cannon, Correll, Byrne, Carr, Chen, Gorwood, Johnson, Kärkkäinen, Krystal, Lee, Lieberman, López-Jaramillo, Männikkö, Phillips, Uchida, Vieta, Vita and Arango2020). Estimates from a Global Burden of Diseases study showed that the COVID-19 pandemic led to a 27.6% increase in major depressive disorders and a 25.6% increase in anxiety disorders globally (Santomauro et al., Reference Santomauro, Mantilla Herrera, Shadid, Zheng, Ashbaugh, Pigott, Abbafati, Adolph, Amlag, Aravkin, Bang-Jensen, Bertolacci, Bloom, Castellano, Castro, Chakrabarti, Chattopadhyay, Cogen, Collins, Dai, Dangel, Dapper, Deen, Erickson, Ewald, Flaxman, Frostad, Fullman, Giles, Giref, Guo, He, Helak, Hulland, Idrisov, Lindstrom, Linebarger, Lotufo, Lozano, Magistro, Malta, Månsson, Marinho, Mokdad, Monasta, Naik, Nomura, O’Halloran, Ostroff, Pasovic, Penberthy, Reiner, Reinke, Ribeiro, Sholokhov, Sorensen, Varavikova, Vo, Walcott, Watson, Wiysonge, Zigler, Hay, Vos, Murray, Whiteford and Ferrari2021). However, a recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found no changes in general mental health and anxiety symptoms but a minimal worsening of depression symptoms among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Wu, Fan, Dal Santo, Li, Jiang, Li, Wang, Tasleem, Krishnan, He, Bonardi, Boruff, Rice, Markham, Levis, Azar, Thombs-Vite, Neupane, Agic, Fahim, Martin, Sockalingam, Turecki, Benedetti and Thombs2023).

Despite the controversy in mental well-being, there are concerns about the paradoxical reduction in mental healthcare provision during the pandemic as healthcare services prioritized COVID-19 cases (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Steeg, Webb, Kapur, Chew-Graham, Abel, Hope, Pierce and Ashcroft2021). Additionally, containment strategies such as lockdowns and physical distancing, COVID-19-related fears, and worsening financial insecurity may result in the under-diagnosis of mental health conditions (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021; Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Wykes, Galderisi, Nordentoft, Crossley, Jones, Cannon, Correll, Byrne, Carr, Chen, Gorwood, Johnson, Kärkkäinen, Krystal, Lee, Lieberman, López-Jaramillo, Männikkö, Phillips, Uchida, Vieta, Vita and Arango2020). Previous studies have reported significant reductions in primary care contacts for patients with mental health conditions during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic levels in the UK (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Steeg, Webb, Kapur, Chew-Graham, Abel, Hope, Pierce and Ashcroft2021; Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Jenkins, Ashcroft, Brown, Campbell, Carr, Cheraghi-sohi, Kapur, Thomas, Webb and Peek2020). Nevertheless, only a few mental health conditions (i.e., anxiety, depression and eating disorders) or broad categories (i.e., severe mental illness and common mental health problems) were examined in these UK studies over a relatively short follow-up period (up to September 2020). A US study using data from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program also reported a reduction in hospital visits for 10 mental disorders during the pandemic (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Radhakrishnan, Lane, Sheppard, DeVies, Azondekon, Smith, Bitsko, Hartnett, Lopes-Cardozo, Leeb, van Santen, Carey, Crossen, Dias, Wotiz, Adjemian, Rodgers, Njai and Thomas2022). Nonetheless, the study only conducted comparisons between specific periods (i.e., high Delta variant circulation period [July 18 to 14 August 2021] vs. pre-Delta period [April 18 to 15 May 2021]), with the data source limited to emergency departments (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Radhakrishnan, Lane, Sheppard, DeVies, Azondekon, Smith, Bitsko, Hartnett, Lopes-Cardozo, Leeb, van Santen, Carey, Crossen, Dias, Wotiz, Adjemian, Rodgers, Njai and Thomas2022). In contrast, a study in Germany that examined data up to 2020 reported an increase in the diagnosis of anxiety disorders in General Practitioner’s practices between April and December 2020, compared to historical averages (Bohlken et al., Reference Bohlken, Kostev, Riedel-Heller, Hoffmann and Michalowsky2021). A comprehensive evaluation of the changes in the incidence of multiple mental health diagnoses that includes different healthcare settings and covers sufficiently long observational periods during the pandemic across a number of countries is lacking.

Different countries have heterogeneous healthcare systems, which may have been differentially affected by the pandemic. This may, in turn, impact changes in the incidence of mental health diagnoses. The examination of whether and how the incidence of mental health diagnoses changed during the pandemic across countries could help identify potential gaps in existing mental healthcare systems and guide immediate and longer-term responses. In this population-based multinational network study, we aimed to investigate the changes in the number of incident cases and the incidence rates of seven specific mental health diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic in France, Germany, Italy, South Korea, the UK and the US.

Method

Data sources

We used data from nine databases, including six electronic health record databases and three claims-based databases. Electronic health record databases consist of IQVIA Longitudinal Patient Database France (France IQVIA) (Jouaville et al., Reference Jouaville, Miotti, Coffin, Sarfati and Meihoc2015; Kostka et al., Reference Kostka, Duarte-Salles, Prats-Uribe, Sena, Pistillo, Khalid, Lai, Golozar, Alshammari, Dawoud, Nyberg, Wilcox, Andryc, Williams, Ostropolets, Areia, Jung, Harle, Reich, Blacketer, Morales, Dorr, Burn, Roel, Tan, Minty, DeFalco, de Maeztu, Lipori, Alghoul, Zhu, Thomas, Bian, Park, Martínez Roldán, Posada, Banda, Horcajada, Kohler, Shah, Natarajan, Lynch, Liu, Schilling, Recalde, Spotnitz, Gong, Matheny, Valveny, Weiskopf, Shah, Alser, Casajust, Park, Schuff, Seager, DuVall, You, Song, Fernández-Bertolín, Fortin, Magoc, Falconer, Subbian, Huser, Ahmed, Carter, Guan, Galvan, He, Rijnbeek, Hripcsak, Ryan, Suchard and Prieto-Alhambra2022), IQVIA Disease Analyser Germany (Germany IQVIA) (Kostka et al., Reference Kostka, Duarte-Salles, Prats-Uribe, Sena, Pistillo, Khalid, Lai, Golozar, Alshammari, Dawoud, Nyberg, Wilcox, Andryc, Williams, Ostropolets, Areia, Jung, Harle, Reich, Blacketer, Morales, Dorr, Burn, Roel, Tan, Minty, DeFalco, de Maeztu, Lipori, Alghoul, Zhu, Thomas, Bian, Park, Martínez Roldán, Posada, Banda, Horcajada, Kohler, Shah, Natarajan, Lynch, Liu, Schilling, Recalde, Spotnitz, Gong, Matheny, Valveny, Weiskopf, Shah, Alser, Casajust, Park, Schuff, Seager, DuVall, You, Song, Fernández-Bertolín, Fortin, Magoc, Falconer, Subbian, Huser, Ahmed, Carter, Guan, Galvan, He, Rijnbeek, Hripcsak, Ryan, Suchard and Prieto-Alhambra2022), Longitudinal Patient Database Italy (Italy IQVIA) (Kostka et al., Reference Kostka, Duarte-Salles, Prats-Uribe, Sena, Pistillo, Khalid, Lai, Golozar, Alshammari, Dawoud, Nyberg, Wilcox, Andryc, Williams, Ostropolets, Areia, Jung, Harle, Reich, Blacketer, Morales, Dorr, Burn, Roel, Tan, Minty, DeFalco, de Maeztu, Lipori, Alghoul, Zhu, Thomas, Bian, Park, Martínez Roldán, Posada, Banda, Horcajada, Kohler, Shah, Natarajan, Lynch, Liu, Schilling, Recalde, Spotnitz, Gong, Matheny, Valveny, Weiskopf, Shah, Alser, Casajust, Park, Schuff, Seager, DuVall, You, Song, Fernández-Bertolín, Fortin, Magoc, Falconer, Subbian, Huser, Ahmed, Carter, Guan, Galvan, He, Rijnbeek, Hripcsak, Ryan, Suchard and Prieto-Alhambra2022), Ajou University School of Medicine database from South Korea (South Korea AUSOM) (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Ryan, Zhang, Schuemie, Hardy, Kamijima, Kimura, Kubota, Man, Cho, Park, Stang, Su, Wong, Kao and Setoguchi2018), Kangwon National University database from South Korea (South Korea KUN) and IQVIA Medical Research Data UK (UK IMRD) (Gooden et al., Reference Gooden, Gardner, Wang, Chandan, Beane, Haniffa, Taylor, Greenfield, Manaseki-Holland, Thomas and Nirantharakumar2022). Claims-based databases were IBM MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database US (US MDCD) (Li et al., Reference Li, Ostropolets, Makadia, Shoaibi, Rao, Sena, Martinez-Hernandez, Delmestri, Verhamme, Rijnbeek, Duarte-Salles, Suchard, Ryan, Hripcsak and Prieto-Alhambra2021), IBM MarketScan Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Database US (US MDCR) (Li et al., Reference Li, Ostropolets, Makadia, Shoaibi, Rao, Sena, Martinez-Hernandez, Delmestri, Verhamme, Rijnbeek, Duarte-Salles, Suchard, Ryan, Hripcsak and Prieto-Alhambra2021) and IQVIA Open Claims US (US Open Claims) (Kostka et al., Reference Kostka, Duarte-Salles, Prats-Uribe, Sena, Pistillo, Khalid, Lai, Golozar, Alshammari, Dawoud, Nyberg, Wilcox, Andryc, Williams, Ostropolets, Areia, Jung, Harle, Reich, Blacketer, Morales, Dorr, Burn, Roel, Tan, Minty, DeFalco, de Maeztu, Lipori, Alghoul, Zhu, Thomas, Bian, Park, Martínez Roldán, Posada, Banda, Horcajada, Kohler, Shah, Natarajan, Lynch, Liu, Schilling, Recalde, Spotnitz, Gong, Matheny, Valveny, Weiskopf, Shah, Alser, Casajust, Park, Schuff, Seager, DuVall, You, Song, Fernández-Bertolín, Fortin, Magoc, Falconer, Subbian, Huser, Ahmed, Carter, Guan, Galvan, He, Rijnbeek, Hripcsak, Ryan, Suchard and Prieto-Alhambra2022). Detailed descriptions of these databases, including their representativeness, are presented in eTable 1 in Supplement and have been previously reported (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Lau, Chai, Torre, Howard, Liu, Lin, Yin, Fortin, Kern, Lee, Park, Jang, Chui, Li, Reich, Man and Wong2023).

All databases were mapped to the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model (CDM), which ensures that studies could be locally executed at contributing centres in a consistent and standardized manner without modification (Hripcsak et al., Reference Hripcsak, Duke, Shah, Reich, Huser, Schuemie, Suchard, Park, Wong, Rijnbeek, van der Lei, Pratt, Norén, Li, Stang, Madigan and Ryan2015). OMOP CDM is maintained by the Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) Network, an interdisciplinary initiative applying publicly available data analytic solutions to healthcare databases to improve human health and wellbeing (Hripcsak et al., Reference Hripcsak, Duke, Shah, Reich, Huser, Schuemie, Suchard, Park, Wong, Rijnbeek, van der Lei, Pratt, Norén, Li, Stang, Madigan and Ryan2015).

Study design and participants

The study period was defined as between January 2017 and 1 month before the latest available month for data in 2021 within each database (considering the potential delay in recording relevant diagnoses into systems and the number of records in the latest available month might be underestimated), which varied between databases. The study end date for each database is shown in Table 1. Our current datasets included diagnoses from various visit formats, including inpatient visits, outpatient visits and telehealth consultations. All individuals who received any diagnoses of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol misuse or dependence, substance misuse or dependence, bipolar disorders, personality disorders or psychoses (including schizophrenia) during the study period, and had at least 365 days of observation time before the first diagnosis of a mental health condition of interest (index date), were extracted from databases. Only the first diagnosis during the study period was included in the analysis to identify incident cases. A 1-year window prior to the index date was used as a screening period for potentially prevalent cases. All individuals were followed from the index date until the end of continuous enrolment (for UK IMRD, US MDCD and US MDCR) or the last healthcare encounter (for France IQVIA, Germany IQVIA, Italy IQVIA, South Korea AUSOM, South Korea KUN and US Open Claims).

Table 1. Total number of unique individuals, incident cases and the incidence of seven mental health diagnoses in each year between 2017 and 2021 in each database

a The full-year data in 2021 were not available at the time of analyses.

b The total number includes all people between January 2016 to the latest available month in 2021 for each database.

Exposure period and outcome

The exposure started from the introduction of national restrictions and containment strategies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). According to the Stringency Index developed by the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker project (Hale et al., Reference Hale, Angrist, Goldszmidt, Kira, Petherick, Phillips, Webster, Cameron-Blake, Hallas, Majumdar and Tatlow2021), all countries included in our study started introducing strict lockdown measures in March 2020 (eFig. 1 in Supplement) (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Lau, Chai, Torre, Howard, Liu, Lin, Yin, Fortin, Kern, Lee, Park, Jang, Chui, Li, Reich, Man and Wong2023; Hale et al., Reference Hale, Angrist, Goldszmidt, Kira, Petherick, Phillips, Webster, Cameron-Blake, Hallas, Majumdar and Tatlow2021). We thus divided the study time into three periods: the pre-pandemic period (January 2017 to February 2020), transition period (March 2020) and post-introduction period (April 2020 to the end of the study period).

The outcomes of this study were the changes in the number of incident cases and the incidence rates of the seven mental health diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diagnostic codes used for the ascertainment of these mental health conditions were shown in eTable 2 in Supplement.

Statistical analysis

For each database, the incidence rates for each mental diagnosis between 2017 and 2021 were calculated by dividing the total number of incident cases per month or year by the total number of all unique individuals during the same period. The monthly number of incident cases and the incidence in 2020 and 2021 were compared to 3-year averages in the same months between 2017 and 2019.

Two interrupted time-series analyses were conducted to estimate the impact of the national restrictions and containment strategies on the number of incident cases and the incidence of mental health diagnoses separately, using the quasi-Poisson regression models. Data in the transition period (March 2020) were excluded to account for the time people took to react to the lockdown restrictions (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). Time (in months) was included as a continuous variable in the model to account for the underlying pre-pandemic trend. Pandemic restriction status was measured by a binary variable (0: pre-pandemic period; 1: post-introduction period) to quantify the immediate change (i.e., level change) in the number of incident cases and the incidence following the introduction of national restrictions and containment strategies. An interaction term between time and pandemic restrictions was used to estimate the gradual change (i.e., slope change) after the restrictions were introduced. All parameters were expressed as rate ratios (RRs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The Fourier term was included to control for seasonality and other long-term trends (Bhaskaran et al., Reference Bhaskaran, Gasparrini, Hajat, Smeeth and Armstrong2013; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Karahalios, Forbes, Taljaard, Grimshaw and McKenzie2021b). The Newey-West standard errors were calculated to correct the possible autocorrelation and possible heteroscedasticity (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Forbes, Karahalios, Taljaard and McKenzie2021a, Reference Turner, Karahalios, Forbes, Taljaard, Grimshaw and McKenzie2021b).

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted by using different transition periods: i) February 2020 and ii) from March to April 2020, to estimate the effect of misclassification of the transition period. All analyses were performed in R software (version 4.1.2) (R Core Team, 2022).

The current study was part of a multinational project entitled ‘Covid-19 pandEmic impacts on mental health Related conditions Via multi-database nEtwork: a LongitudinaL Observational study (CERVELLO)’. The study protocol of CERVELLO was drafted, reviewed and iteratively updated by an international team of academic, clinical and industry stakeholders through the OHDSI network. The protocol and all analytical codes of CERVELLO are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/ohdsi-studies/CervelloPrevalence).

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Results

A total of 629,712,954 individuals were included in nine databases between 2016 and 2021, ranging from 280,926 individuals in South Korea KUN to 561,757,636 individuals in US Open Claims. Eight of nine databases had a higher proportion of females than males (average proportions of female individuals across the study period ranged from 50.42% in the UK to 57.32% in France), whereas South Korea AUSOM included an average of 49.43% female individuals (eTable 3 in Supplement). Individuals aged below 25 years accounted for 54.96% in US MDCD, and individuals aged 65 years or older accounted for 98.57% in US MDCR, representing the youngest and oldest population among the databases. Regarding the remaining databases, except for the UK and US Open Claims, individuals aged 45–64 years predominated for all databases, ranging from 28.83% in France to 34.88% in South Korea AUSOM.

In most databases, the highest yearly number of incident cases and the incidence were observed in the year 2017 (Table 1). For instance, in France, anxiety disorders had the highest number of incident cases and the incidence (93,626 and 1.52%, respectively) in 2017, while the highest yearly number of incident cases and incidence was observed in depressive disorders in the remaining countries except for South Korea and the UK (Germany: 127,902 [1.11%]; Italy 21,846 [1.59%]; US MDCD: 561,164 [4.16%]; US MDCR: 100,819 [7.20%]; US Open Claims: 8,809,768 [2.28%]).

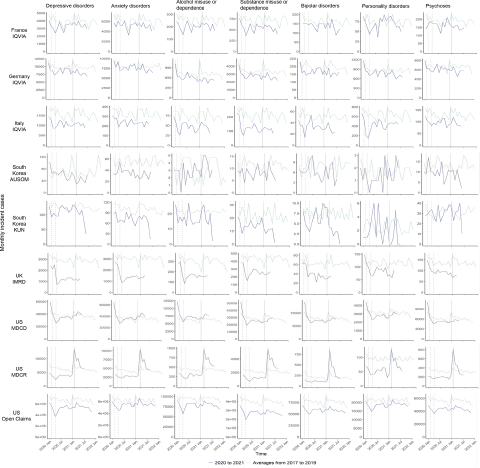

Figure 1 shows the monthly number of incident cases of seven mental health diagnoses. Compared to the 3-year historical level, we found significant decreases in the number of incident cases of all mental health diagnoses during the initial phase of the pandemic in France, Italy, South Korea, the UK and the US, except for depressive disorders and psychoses in South Korea AUSOM and psychoses in South Korea KUN. After the acute phase of the pandemic, the monthly number of incident cases gradually increased but remained lowered than the 3-year historical level by the end of the study period in most countries. However, in US MDCD and MDCR, the incident cases of most mental health diagnoses recovered to or exceeded pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 1. Monthly number of incident cases of seven mental health diagnoses in 2020 and 2021 and historical averages for that month from 2017 to 2019. Vertical dashed lines represent February and April 2020. The vertical solid line represents January 2021.

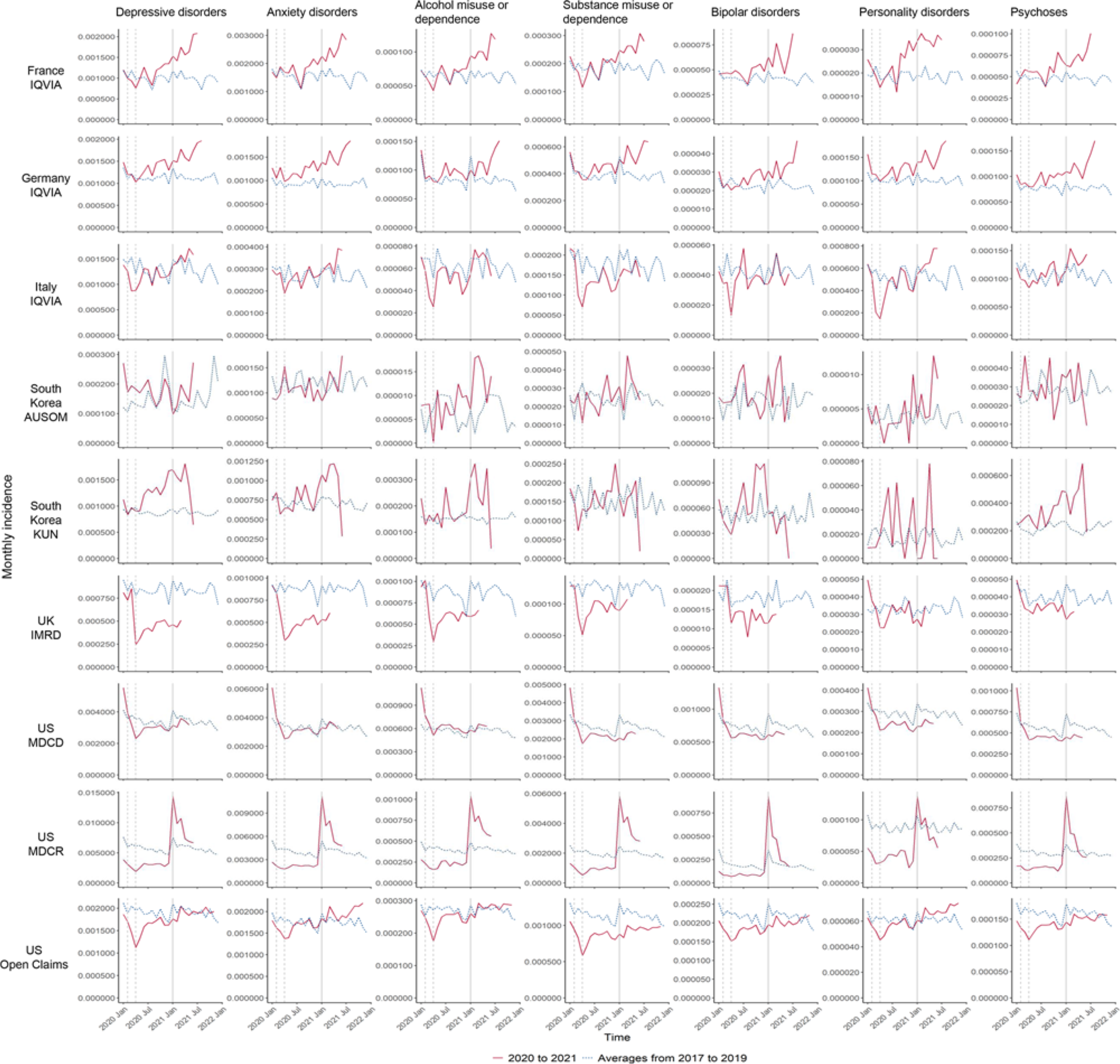

Figure 2 shows the monthly incidence of seven mental health diagnoses. Similarly, a considerable decline in the incidence of mental health diagnoses was observed during the early stage of the pandemic in France, Italy, South Korea KUN, the UK and the US, with the exception of anxiety and bipolar disorders, and psychoses in France, and depressive disorders, alcohol misuse or dependence, and psychoses in South Korea KUN. There was no reduction in any mental health diagnoses in Germany and South Korea AUSOM. Since mid-2020, the incidence of all diagnoses gradually returned to or surpassed the 3-year historical level, except for some conditions which remained below (i.e., bipolar disorders in South Korea KUN, all conditions except for personality disorders in the UK, all conditions except for depressive and anxiety disorders, and alcohol misuse or dependence in US MDCD, and personality disorders in US MDCR). Patterns varied by country. For example, the incidence of mental health diagnoses in France has returned to the historical level since mid-2020, whilst the increase only became apparent in US MDCR in early 2021.

Figure 2. Monthly incidence of seven mental health diagnoses in 2020 and 2021 and historical averages for that month from 2017 to 2019. Vertical dashed lines represent February and April 2020. The vertical solid line represents January 2021.

Figure 3 shows results from interrupted time-series analyses of the monthly number of incident cases of seven mental health diagnoses. Substantial decreases in the number of incident cases were observed immediately following the introduction of restrictions (i.e., level change) in common mental illnesses (i.e., depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol misuse or dependence and substance misuse or dependence) in the UK and all mental health conditions in the US, ranging from the RR of 0.005 (95% CI, 0.001–0.022) in substance misuse or dependence in US MDCR to 0.677 (0.516–0.889) in alcohol misuse or dependence in US Open Claims (Fig. 3a and eTable 4 in Supplement). All these were followed by a gradual increase (i.e., slope change) after the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 3b and eTable 4 in Supplement).

Figure 3. (a) Estimates of the immediate change (i.e., level change) in monthly number of incident cases of seven mental health diagnoses. (b) Estimates of the gradual change (i.e., slope change) in monthly number of incident cases of seven mental health diagnoses.

Results from interrupted time-series analyses of the monthly incidence of seven mental health diagnoses indicated that for most databases, the incidence trends were consistent across mental health conditions (Fig. 4). Substantial immediate decreases in the incidence of all mental health diagnoses were found in all countries except for South Korea. In the UK, a significant decline was also only observed in common mental illnesses. The immediate changes ranged from the RR of 0.002 (95% CI, 0.000–0.007) in substance misuse or dependence in US MDCR to 0.422 (0.328–0.543) in alcohol misuse or dependence in US Open Claims (Fig. 4a and eTable 7 in Supplement). Figure 4b and eTable 7 in Supplement show that the incidence of mental health diagnoses in these databases then increased gradually after the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 4. (a) Estimates of the immediate change (i.e., level change) in monthly incidence of seven mental health diagnoses. (b) Estimates of the gradual change (i.e., slope change) in monthly incidence of seven mental health diagnoses.

eFigures 2 and 3 show the observed and predicted trends based on the interrupted time-series models of incident cases and the incidence from interrupted series analyses, respectively. Results from sensitivity analyses were generally consistent with our main results (eTables 5–6 and 8–9 in Supplement).

Discussion

In this multinational network study, we compared the number of incident cases and the incidence of seven mental health diagnoses before and during the COVID-19 pandemic using population-representative electronic health records and claims data from nine databases across six countries. We found that the incident cases and the incidence of mental health diagnoses declined considerably after the introduction of national restrictions and containment strategies, and it gradually returned to or exceeded the pre-pandemic level in 2021 in most countries.

Previous studies reported significant declines in both hospital admissions and emergency department visits in many countries, including the US, the UK, Canada, Italy, Spain, France and Germany, indicating the dynamic adaptation of healthcare systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Di Domenico et al., Reference Di Domenico, Pullano, Sabbatini, Boëlle and Colizza2020; Jaehn et al., Reference Jaehn, Holmberg, Uhlenbrock, Pohl, Finkenzeller, Pawlik, Quack, Ernstberger, Rockmann and Schreyer2021; Mulholland et al., Reference Mulholland, Wood, Stagg, Fischbacher, Villacampa, Simpson, Vasileiou, McCowan, Stock, Docherty, Ritchie, Agrawal, Robertson, Murray, MacKenzie and Sheikh2020; Nourazari et al., Reference Nourazari, Davis, Granovsky, Austin, Straff, Joseph and Sanchez2021; Nuñez et al., Reference Nuñez, Sallent, Lakhani, Guerra-Farfan, Vidal, Ekhtiari and Minguell2020; Rennert-May et al., Reference Rennert-May, Leal, Thanh, Lang, Dowling, Manns, Wasylak and Ronksley2021; Scaramuzza et al., Reference Scaramuzza, Tagliaferri, Bonetti, Soliani, Morotti, Bellone, Cavalli and Rabbone2020). From the perspective of mental health conditions, two studies from the UK suggested that the primary care-recorded diagnoses of depression, anxiety disorders and common mental health problems had reduced by 43.0%, 47.8% and 50%, respectively, in April or May 2020 compared to the expected level (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Steeg, Webb, Kapur, Chew-Graham, Abel, Hope, Pierce and Ashcroft2021; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Jenkins, Ashcroft, Brown, Campbell, Carr, Cheraghi-sohi, Kapur, Thomas, Webb and Peek2020). Another population-based study in the UK found considerable reductions in the incidence of primary care contacts for depression (odds ratio = 0.53), anxiety disorders (0.67) and severe mental illness (0.80) after 29 March 2020 and until 18 July 2020 (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021). Our study not only provides more up-to-date data in the UK but for the first time also examined the number of incident cases and the incidence of diagnoses of mental health conditions during the pandemic in five other countries (i.e., France, Germany, Italy, South Korea and the US). There are some possible explanations for the decline in diagnoses. First, individuals with mild mental health issues might prefer not to visit clinics or hospitals for treatment because of the fear of cross-infection by COVID-19 (Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Wykes, Galderisi, Nordentoft, Crossley, Jones, Cannon, Correll, Byrne, Carr, Chen, Gorwood, Johnson, Kärkkäinen, Krystal, Lee, Lieberman, López-Jaramillo, Männikkö, Phillips, Uchida, Vieta, Vita and Arango2020). Second, to reduce COVID-19 transmission, strict infection control strategies were implemented in almost all mental health service premises, including reducing the number of appointments, tightening the admission criteria and treating urgent cases only, which increased barriers to accessing mental health support (Percudani et al., Reference Percudani, Corradin, Moreno, Indelicato and Vita2020; Sheridan Rains et al., Reference Sheridan Rains, Johnson, Barnett, Steare, Needle, Carr, Lever Taylor, Bentivegna, Edbrooke-Childs, Scott, Rees, Shah, Lomani, Chipp, Barber, Dedat, Oram, Morant, Simpson, Papamichail, Moore, Jeffery, De Estrada, Hallam, Lloyd-Evans, Contreras, Serna, Ntephe, Lamirel, Cooke, Pearce, Lemmel, Koutsoubelis, Cragnolini, Harju-Seppänen, Wang, Botham, Abdou, Krause, Turner, Poursanidou, Gruenwald, Jagmetti, Mazzocchi, Tomaskova, Montagnese, Mahé, Schlief, Günak, Leverton, Lyons, Vera, Gao, Griffiths, Lane, Busato, Ledden, Mac-Ginty, Hardt, Orlando, Gillard, Jeynes, Ondrušková, Stefanidou, Foye, Tzouvara and Cavero2021; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Zhao, Liu, Li, Zhao, Cheung and Ng2020). Additionally, it is also possible that individuals have altruistically followed the government’s advice to ‘Stay at Home’ for the broader purpose of the well-being of the community and protecting the healthcare system (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Stedman and Heald2021). Due to concerns about COVID-19 infection, restrictions on outdoor activities and travelling, and altruism to stay home, individuals with mental health conditions may have opted not to seek mental healthcare during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported that the prevalence of people experiencing symptoms of mental health conditions has increased during the pandemic (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Barnett, Greenburgh, Pemovska, Stefanidou, Lyons, Ikhtabi, Talwar, Francis, Harris, Shah, Machin, Jeffreys, Mitchell, Lynch, Foye, Schlief, Appleton, Saunders, Baldwin, Allan, Sheridan-Rains, Kharboutly, Kular, Goldblatt, Stewart, Kirkbride, Lloyd-Evans and Johnson2023; Cénat et al., Reference Cénat, Blais-Rochette, Kokou-Kpolou, Noorishad, Mukunzi, McIntee, Dalexis, Goulet and Labelle2021; Troglio da Silva and Neto, Reference Troglio da Silva and Neto2021; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Jia, Shi, Niu, Yin, Xie and Wang2021; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Lipsitz, Nasri, Lui, Gill, Phan, Chen-Li, Iacobucci, Ho, Majeed and McIntyre2020), we found substantial reductions in the incident diagnoses of mental health conditions. This might indicate that many people experiencing mental health problems, who would have expected to benefit from receiving mental healthcare, did not access health services during the pandemic. It is reasonable to speculate that there would be an increase in the demand for mental health services following the early stage of this pandemic. This hypothesis was supported by three studies in the UK, which observed increasing trends in mental health condition diagnoses following the acute phase of the pandemic (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Steeg, Webb, Kapur, Chew-Graham, Abel, Hope, Pierce and Ashcroft2021; Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick, Carreira, Matthews, Bidulka, Gayle, Forbes, Cook, Wong, Strongman, Wing, Warren-Gash, Cadogan, Smeeth, Hayes, Quint, McKee and Langan2021; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Jenkins, Ashcroft, Brown, Campbell, Carr, Cheraghi-sohi, Kapur, Thomas, Webb and Peek2020). However, the observation period of these studies ended in September 2020, and almost all studies found that the rate of diagnoses of the studied conditions had not returned to the expected (or pre-pandemic) levels. There has been an urgent need for data after September 2020 to comprehensively evaluate the long-term impact of COVID-19 on mental health conditions (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Steeg, Webb, Kapur, Chew-Graham, Abel, Hope, Pierce and Ashcroft2021). In addition to the potential surge in demand as restrictions were lifted, the unmet need and delays in diagnosis may have exacerbated symptoms of mental health conditions, resulting in an increased risk of self-harm, suicide and other adverse outcomes (Chai et al., Reference Chai, Luo, Wong, Tang, Lam, Wong and Yip2020; Kisely et al., Reference Kisely, Scott, Denney and Simon2006; Qin, Reference Qin2011). Our results suggest that there was a sustained period of unmet need during the early phase of the pandemic, and the incident cases and the incidence of mental health diagnoses in most countries continuously increased since mid-2020, often recovering to or exceeding historical averages. As a result of increased incidences of mental health disorders post-pandemic, healthcare systems might be at risk of being overloaded. Findings from the current study should be used by healthcare providers to plan future service provision. Sustained adaptations may be necessary to mitigate the mental healthcare burden that is directly or indirectly caused by delays in diagnoses and treatment of mental health conditions. There should be a focus on the importance of maintaining accessibility to mental health help-seeking and intervention by leveraging technology with tele/digital means and collaborative community support to cope with the abrupt hidden mental problems followed by overcrowding across the acute and post-pandemic period.

To our best knowledge, this study is the first to systematically examine the effect of national COVID-19 restrictions and policies on the diagnoses of a wide range of mental health conditions across countries, with the longest follow-up time since the start of the pandemic. Our study is a collaborative OMOP CDM project in which the same coding and analytical practice enabled rapid and timely investigation of different geographical areas and healthcare systems in a standard and systematic way (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Lau, Chai, Torre, Howard, Liu, Lin, Yin, Fortin, Kern, Lee, Park, Jang, Chui, Li, Reich, Man and Wong2023; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Torre, Man, Stewart, Seager, Van Zandt, Reich, Li, Brewster, Lip, Hingorani, Wei and Wong2022). Data from large and diverse databases allowed us to understand how these vulnerable populations were affected by the pandemic across healthcare systems.

This study has limitations. Firstly, the databases included in this research consisted of medical records from different healthcare settings, ranging from primary care to insurance claims. Therefore, the comparison of the absolute incident cases and incidence between different databases or countries should be with caution. However, this would not affect within database comparisons. Secondly, an individual with multiple insurance plans could have multiple identification numbers in the US Open Claims database. This could lead to an overestimation of the total number of patients in the database. However, as our analyses were based on the monthly number of incident cases and incidence, it is unlikely that patients would have multiple insurance plans in the same month. Hence, the effect on the estimation is expected to be minimal. Thirdly, findings generated from some databases may have limited generalizability. For example, South Korean databases only contained data from two hospitals and were more likely to capture people with severe symptoms. The mental health services for these severe cases might have been less affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which could be a possible explanation for the non-significant reduction in the diagnosis of mental health conditions in South Korea. Further investigations incorporating population-level data sources from South Korea are required to validate our results. Additionally, more than 99% of people in the US MDCR database were aged 45 years and above. However, results from this older population were consistent with that observed in US Open Claims, which consists of all-age patients. Finally, in addition to mental health conditions, the COVID-19 pandemic may have also resulted in a decline in the diagnosis of physical diseases, such as cardiovascular events and metabolic disorders. Further multinational investigation is warranted to explore the changes in the diagnoses of physical diseases during the pandemic.

Conclusion

There was a reduction in the incident cases and the incidence of mental health diagnoses in many countries immediately after the implementation of stringent national COVID-19 containment strategies. Since the incident cases and the incidence of mental health diagnoses returned to the pre-pandemic level by 2021 in most countries, stakeholders and mental healthcare providers should prepare for potentially delayed but increased demand for care in response to the patients who were not able to access healthcare services for appropriate and timely diagnoses. For example, enhancing population knowledge about mental health and COVID-19 and leveraging technological advances such as telehealth and remote care delivery can help reduce barriers to treatment and improve access to mental health interventions and care. Fostering partnerships between mental health providers, schools, workplaces, community organizations and service users can create a comprehensive mental healthcare network for implementing effective public mental health interventions. Furthermore, the pandemic presents a crucial opportunity to mitigate disparities in previous mental healthcare provision. By prioritizing high-quality and equitable mental healthcare, the current mental healthcare delivery system can be improved to meet the rising demand and future-proof services against further pandemic threats.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796024000088.

Availability of Data and Materials

The protocol and analytical codes of this study are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/ohdsi-studies/CervelloPrevalence). Data used in this are not publicly available due to restrictions from the data providers.

Acknowledgements

Analyses of the South Korea databases were performed using FEEDER-NET (Evadne Inc., https://feedernet.com), a healthcare big-data platform.

Author Contributions

Y. Chai, K. Man, H. Luo, W. Lau and I. Wong contributed to the conception of the work. All authors designed the study. Y. Chai, W. Lau, H. Luo, C. Torre, X. Lin, C. Yin, S. Fortin, D. Lee and R. Park conducted the statistical analysis. Y. Chai, K. Man and W. Lau drafted the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Y. Chai and K. Man are co-first authors. W. Lau can also be contacted for correspondence [email protected].

Financial support

This work was supported by Collaborative Research Fund, University Grants Committee, HKSAR Government (C7154-20GF).

Competing interests

K. Man reports grants from the CW Maplethorpe Fellowship, National Institute of Health Research, UK, Hong Kong Research Grant Council and the European Commission Horizon 2020 Framework, personal fees from IQVIA and grants from Amgen and GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work; H. Luo reports grants from Research Grants Council of Hong Kong, outside the submitted work; J. Hayes reports grants from UKRI, NIHR UCLH Biomedical Research Centre, and Wellcome Trust and Consultancy Fees from Wellcome Trust and juli Health, outside the submitted work; E. Chan reports grants from Research Grants Council of Hong Kong, Research Fund Secretariat of the Food and Health Bureau of Hong Kong, National Natural Science Fund of China, Wellcome Trust, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, Amgen, Takeda and Narcotics Division of the Security Bureau of Hong Kong; honorarium from Hospital Authority; outside the submitted work; S. Fortin is an employee of Johnson and Johnson and owns stock in Johnson and Johnson; D. Kern is an employee of Janssen R&D, a subsidiary of Johnson and Johnson, and owns stock in Johnson and Johnson; W. Lau reports receiving grants from AIR@InnoHK administered by the Innovation and Technology Commission of Hong Kong outside the submitted work; I. Wong reports grants from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, Bayer, GSK and Novartis, the Hong Kong RGC, and the Hong Kong Health and Medical Research Fund in Hong Kong, National Institute for Health Research in England, European Commission, National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia, consulting fees from IQVIA, payment for expert testimony and is an independent non-executive director of Jacobson Medical in Hong Kong, outside of the submitted work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical standards

The data partners have obtained institutional review board exemption for their participation in this study. Informed consent was waived because the study used deidentified data and no patients were contacted.