A central question for social scientists who study law concerns the mechanisms by which law affects human behavior; that is, how does law work? Of course, there is no simple answer to this question because a great variety of factors shape and control the impact of law. Perhaps the most comprehensively researched factor is sanctions. For economists, questions about the effect of law on human behavior begin (and generally end) with the assumption that behavior responds to rewards and punishments. That is, people obey law to the extent that legal sanctions raise the expected cost of noncompliance beyond the expected benefits (Reference BeckerBecker 1968).

On the other hand, scholars working from the perspective of other social sciences (anthropologists, psychologists, sociologists, and political scientists, among others) recognize that motives for compliance are often more complex than the stark cost-benefit analysis assumed by economists (Reference StrykerStryker 1994; Reference FriedmanFriedman 2005). To this end, many social scientists who study legal compliance emphasize that people generally obey law to the extent that they perceive law and legal actors as authoritative and legitimate. There are many examples from many different domains. When police treat people with respect and dignity, they gain legitimacy, and as a result, the cooperation and compliance of citizens (Reference TylerTyler 1990; Tyler & Fagan n.d.). Tax authorities gain more compliance when they treat people fairly and respectfully (Reference WenzelWenzel 2002; Reference MurphyMurphy 2005). The institutional legitimacy of the U.S. Supreme Court has remained steady over many years, and this reserve of goodwill is thought to increase the likelihood of acceptance of unpopular court decisions (Reference Caldeira and GibsonCaldeira & Gibson 1992; Reference GibsonGibson 2007). Indeed, law is a complex structure, and its perceived legitimacy varies widely, over cultures, times, and domains of its everyday instantiation (Reference Sarat and KearnsSarat & Kearns 1993:9; Reference SuchmanSuchman 1997:486–90; Reference CalavitaCalavita 2001).

The two approaches of sanctions and legitimacy are quite different from one another. The approach that focuses on law working primarily through sanctions is most readily identified with the law-and-economics movement; the approach that focuses on law working through legitimacy is commonly identified with the law-and-society movement. Together these two different approaches dominate the social science debate on legal compliance. In this article, we aim to bridge these two approaches (see generally Reference EdelmanEdelman 2004) by empirically demonstrating a third, complementary way that law influences behavior. Our approach incorporates elements of the law-and-economics approach in its assumptions about self-interested human behavior, as well as elements of the law-and-society approach in its emphasis on the social actor in a social context.

In recent years, several theorists (e.g., Reference CooterCooter 1998; Reference Garrett, Weingast, Goldstein and KeohaneGarrett & Weingast 1993; Reference Ginsburg and McAdamsGinsburg & McAdams 2004; Reference Hardin, Grofman and WittmanHardin 1989; Reference Hay and ShleiferHay & Shleifer 1998; Reference PosnerPosner 2000; Reference McAdams and NadlerMcAdams & Nadler 2005) have argued that in certain circumstances law induces compliance merely by its ability to make a particular behavior salient. Law tends to draw attention to the behavior it demands and, in certain situations, the fact that everyone's attention is focused on a particular behavior creates an incentive to engage in it. Specifically, when the parties involved have some common incentive to “coordinate” their behavior, the law's articulation of a behavior will tend to create self-fulfilling expectations that it will occur. We call this “the focal point theory” of legal compliance (Reference McAdams and NadlerMcAdams & Nadler 2005).

According to the theory, the focal effect of the law on behavior depends neither on law's legitimacy nor on the existence of legal sanctions. Consider a simple example of coordination: drivers in a new society (with no prior custom) are likely to follow a rule that says “drive on the right” primarily because they wish to avoid collisions; fear of sanctions and respect for legal authorities are rather beside the point here. Thus in situations where people have an incentive to coordinate their behavior, law can provide a framework for understanding and predicting what others are likely to do. The shadow cast by law in these situations helps people predict not what a court is likely to do (Reference Mnookin and KornhauserMnookin & Kornhauser 1979) but rather what other people who are also aware of the law are likely to do.

The focal point claim is modest. Those advocating this understanding of law do not seek to displace the dominant theories of legal compliance, but merely to supplement them. Indeed, one reason that social science has generally ignored the focal point effect of law, we believe, is that other compliance mechanisms are usually more important. Thus if legal compliance were not so significant, it might not much matter that we do not fully understand the reasons for compliance. We might be content to know that sanctions and legitimacy generate most of the compliance we observe without worrying about what generates the rest. By contrast, we assume that the issue of legal compliance is a matter of paramount concern, and that scholars and policy makers wish to gain a full understanding about the causal mechanisms that produce compliance with the law. If so, then it is important to understand and measure all mechanisms of compliance, including law's focal effect—that is, the degree to which the shadow cast by a legal rule produces self-fulfilling expectations of the behavior the law demands. (Similarly, we should be concerned about other expressive theories of compliance that we do not explore here, e.g., Reference Dharmapala and McAdamsDharmapala & McAdams 2003; Reference McAdamsMcAdams 2000.)

Another reason that social science has failed to address the focal point theory is that it is exceedingly difficult to empirically test in the field. It is possible in the field to obtain measures of the perceived threat of legal sanctions as well as the perceived legitimacy of law or legal actors, so one can plausibly separate the effects of the sanctions and legitimacy (e.g., Reference Grasmick and GreenGrasmick & Green 1980; Reference SilbermanSilberman 1976; Reference TylerTyler 1990). By contrast, in the field one cannot easily test the focal point theory. The focal effect works by creating salience, yet the salience of a legal rule itself is nearly always bound up with the salience of legitimacy and of sanctions. We have therefore found it necessary to test the focal point effect experimentally, where we can carefully control the different elements of law to see if and how salience influences behavior independently of legitimacy or sanctions.

In previous experiments (Reference McAdams and NadlerMcAdams & Nadler 2005), we conducted our first test of the focal point theory in a highly abstract setting. To avoid the effect of legal legitimacy and sanctions, we made no reference to law at all. Instead, pairs of participants interacted in a game that paid out real money based on each player's selection. (The game created some conflict because different outcomes paid unequal amounts of money, so one outcome was better for one participant and the other was better for the other participant.) We enhanced the salience of certain choices in the game by issuing a recommendation from a third party (either a mechanical spinner or another participant). We found that third-party messages highlighting a particular outcome influenced players to select that outcome, even though there were no sanctions for ignoring the message and even when the source of the message was not imbued with legitimacy. This experiment demonstrated that, despite the conflict between the individuals playing the game, a third party's “mere” expression could influence how the players behaved.

In this prior work, we argued that the experiment demonstrated the focal effect of law based on an inference that law is a type of third-party expression. In other words, we interpreted our results as demonstrating that, in certain circumstances, any third party expression can influence behavior by making certain outcomes salient. So we asserted that, if expression as weak as a spinner or randomly selected individual can influence behavior merely by expressing it, then law can do the same. But the last step of our reasoning was not directly tested by the experiment. Because we used an abstract design making no mention of law, we could not directly test whether law specifically has this focal effect. By contrast, in the two experiments we report here, we supply the missing piece of the puzzle by directly testing the effect of “law.” To do so, we used two highly contextualized settings, as explained in detail below. Our results are consistent with our prior finding that, controlling for legitimacy and sanctions, law can influence behavior expressively. In particular, we find that people are more likely to indicate a willingness to obey law in those precise circumstances where the theory predicts a focal effect than in circumstances where the theory predicts no focal effect.

We proceed as follows. The first section explains the focal point theory. The second and third sections report two new contextualized experiments. The final section concludes.

The Focal Point Theory of Legal Compliance

The theory we test arises out of the economic theory of strategic interaction—“game theory”—which we present in informal terms. The focal point theory of expressive law relies on four claims: (1) that individuals' need for “coordination” is pervasive; (2) that where individuals need to coordinate among possible behaviors, any feature of the environment that causes one behavior to be salient will tend to produce that behavior; and (3) that public third-party expression, by publicly endorsing a particular behavior, tends to make that behavior salient. If so, then we claim (4) that law is one form of third-party expression capable of making salient a behavior and thereby producing self-fulfilling expectations that it will occur. The last claim is the one we test in the experiments reported here. We explain each claim in turn.

The Need for Coordination Is Pervasive

Many theorists overlook the pervasiveness of coordination in social life. In a pure coordination game, two individuals each make some choice where each cares only about “matching” or coordinating one's choice with the other. For example, two people are trying to find each other and must choose between going to place A and going to place B. Or two drivers in a new society must decide whether to drive on the left or the right. In general, the coordination problem is that one person's best choice depends on what the second person does, but the second person's best choice depends on what the first person does. In the pure coordination situation, the interests of both people are entirely common. Both care only about matching their outcomes, such as both choosing A or both choosing the right side of the road. There is no conflict.

If the need for coordination existed only in this pure form, it would not have much relevance to the social world. But in more complex situations, with conflict, there may also be a strong element of coordination. In other words, the world does not consist of only (1) situations of pure coordination and (2) situations of pure conflict, but also (3) mixed-motive situations of conflict and coordination. For this reason, the need for coordination is socially pervasive (Reference SchellingSchelling 1960; Reference SugdenSugden 1986).

Many traffic situations illustrate this mix of conflict and coordination. Two drivers approach an intersection on perpendicular streets where each wishes to proceed first through the intersection. Or two drivers traveling in opposite directions approach a one-lane bridge that each wishes to use first. Or two drivers in merging lanes each wish to get ahead of the other. In each case, there is an element of conflict because each wants to proceed ahead of the other. But there is also a common interest in coordinating to avoid certain outcomes. Most obviously, of the possible outcomes, each regards a collision of the two vehicles as the worst. For any but the most idiosyncratic driver, crashing is worse than letting the other proceed first. Each driver therefore has a common interest in coordinating to avoid a collision. It is also likely that the two drivers have a common interest in avoiding the outcome where both wait for the other to proceed. Not only does that waste time for each, but after they each realize that the other is also waiting, they must face the same situation again—deciding whether to proceed first or wait—which means they again risk the possibility of a collision. Thus the drivers conflict over what is the best outcome, but they have a common interest in coordinating to avoid some outcomes—the collision certainly, and possibly also the mutual wait.

Many kinds of disputes have this structure. For example, two individuals want to sit in the same public area for a time; one wishes to smoke a cigarette, and the other wishes not to be exposed to cigarette smoke. Or two neighbors dispute the exact location of their property line; one wants to plant a tree on the contested land, while the other wants no tree to be planted. Some workers seek to force concessions from an employer by a strike or work slowdown, while other workers insist on avoiding the risk of firing by working at the normal pace. In each case, it is possible that these disputes involve “pure” zero-sum conflict and no element of coordination.

But disputes will contain an element of coordination if there is any outcome the disputing parties jointly regard as the worst possible result. The outcome may be improbable, but if it exists, then the game is no longer one of pure conflict because the disputants share an interest in avoiding this bad result. The most pervasive reason is the potential for violence. However unlikely, illegal violence is usually a background risk of disputing. Much violence that occurs in ostensibly ordered societies involves individuals engaged in “self-help” remedies against someone whom they regard as having infringed on their rights (see, e.g., Reference BlackBlack 1983; Reference GibbsGibbs 1989:35–7; Reference MerryMerry 1981:175–86; Reference Nisbett and CohenNisbett & Cohen 1996). So if two sides in a protracted dispute each regard the outcome of violence as possible and the costs of violence as exceeding the costs of giving in to the other (which will be true if the costs of fighting are high relative to the value at stake), each may regard fighting as the worst possible outcome. This common interest does not end the dispute because each still prefers the other to give in without a fight. If so, then the situation is mixed-motive—mutual conflict coexists with the mutual desire to avoid violence. So an element of coordination can exist in disputes between strangers over smoking, between neighbors over land, and between coworkers over a strike.

What is true of violence is true of other negative consequences of disputing. People may regard, for example, a heated shouting match or an exchange of profane insults as being the worst possible outcome of a dispute. This may be particularly true between people who know each other socially—such as the examples above involving neighbors and coworkers—because the exchange may terminate their relationship. What is true of violence and social disruption may also be true of litigation costs. If the costs of litigating are high relative to the stakes, the worst outcome for both disputants is to litigate, even though each hopes that the threat to litigate will cause the other party to give in. In all of these cases—violence, social disruption, and litigation—the interaction involves mixed motives; even when individuals prefer to get their way in the dispute, the element of coordination remains.

Finally, consider the most well-known “game” in social science: the prisoners' dilemma (PD). In the pure, one-shot PD game, there is no coordination problem because each player has a single best strategy (to defect), regardless of what the other individual does. In the iterated game, however, where two or more individuals interact for the indefinite future, it is possible that the lure of future returns from cooperation will cause the individuals to sustain cooperation (because any individual can sanction past defection with present and future defection). This iterated situation presents a mixed-motive game because there is a mutual desire to avoid the all-defect outcome, even though each individual still prefers to defect while the other cooperates. Of primary concern for the present study, however, an iterated PD contains a powerful element of coordination whenever there is more than one way to cooperate (see Reference Garrett, Weingast, Goldstein and KeohaneGarrett & Weingast 1993). If there is more than one way to “solve” the iterated PD, then the parties must coordinate around just one solution; without a common understanding of what constitutes cooperation and defection, they cannot sustain cooperation.

For example, consider the problem of overfishing. Residents along a bay might face a PD situation in which the noncooperative outcome is that individuals fish beyond a sustainable level. According to the conventional account, iteration may allow the parties to sustain cooperation and solve this “tragedy of the commons.” What is often missed in such examples, however, is that there is more than one possible solution. One might prevent overfishing by limiting the number of people licensed to fish, the number of fish any one person is allowed to catch, or the number of days per year that fishing is permitted. If all residents regard two or more of these regulations to be an improvement over the status quo, then the choice between the regulatory means is partly a matter of coordination. Most likely, residents disagree about which regulation is best, and we have a mixed-motive coordination problem where they mutually prefer the regulatory alternatives to the status quo but disagree as to which regulatory alternative is best. In general, the iterated PD game involves an important element of coordination where there is more than one way to solve it, the people involved disagree about which way is best, but agree that it is better to solve the PD problem than to leave it unaddressed.

Salience Produces Coordination

In situations requiring an element of coordination, anything that makes salient one behavioral means of coordinating tends to produce self-fulfilling expectations that this behavior will result. Decades ago, Nobel Laureate Thomas Reference SchellingSchelling (1960) first explained the significance of these “focal points” in solving coordination problems. The simplest examples involve pure coordination games. For example, suppose you ask two people to try to name the same positive whole number without communicating. Given the infinity of possible solutions, the odds of “matching” seem to be at or near zero, but in this situation most people select a number that seems to stand out from the rest—the number one. If you ask two people at what time of day they would try to meet each other during one day if they had not scheduled a particular time, there again are many logical possibilities, but there is a tendency to select noon. Schelling said that these are “focal points” because some feature of the particular solution not captured by the formal structure of the situation nonetheless draws the attention of the individuals. Individuals do not just thoughtlessly choose the salient solution, but reason about what is likely to be mutually understood as the salient solution (Reference MehtaMehta et al. 1994).

Schelling asserted that what is true of the pure coordination game is also true of the mixed-motive games involving conflict and coordination—that the salience of the outcome will tend to produce self-fulfilling expectations that the outcome will occur. We could imagine this point by introducing a slight degree of conflict in the above examples. Suppose we tell two individuals that they will receive a monetary payoff if they match in naming a positive whole number or time of day and nothing if they fail to match. But suppose we tell both individuals that one of them—Player A—will receive $100 if they match on an odd number and $99 if they match on an even number, while the other—Player B—will receive $100 for an even-numbered match and $99 for an odd-numbered match. The conflict here is trivial compared to the coordination, so we should not expect it to matter. For the positive whole number, B will name the most salient number—one—and accept $99 rather than name a nonfocal even number and risk getting nothing. For the time of day, A will name the salient time—noon—and accept $99 rather than name a nonfocal odd number and risk getting nothing. Although the strength of the focal point effect is a contingent and empirical matter, there is no reason a priori to think that it disappears entirely as the magnitude of the conflict grows. So even if an individual gets $100 from one kind of match and only $10 from another, that person may expect the other to play the salient solution and therefore prefer to play it as well, getting $10 rather than nothing.

We can say the same about the actual mixed-motive games discussed above. Two drivers merging into a single lane will tend to choose the behavior that they regard as mutually salient. If one solution is focal—e.g., the driver on the right proceeds first—then even the driver on the left disadvantaged by that solution will still prefer it to a collision. Expecting the focal solution, the driver on the left will slow down and let the driver on the right merge first.

The same point should apply to other disputes involving a mixed-motive situation. If the two disputants wish to avoid the cost of a fight or social breach, then the existence of a focal solution will create self-fulfilling expectations that the individuals will choose it. For example, Reference SchellingSchelling (1960) mentioned “precedent” as one reason that a particular solution is focal. If the context is a place and time in which nonsmokers have previously deferred to smokers, that behavior is likely to be salient, so nonsmokers will continue to defer. It is possible, of course, that the nonsmoker has internalized a norm of deference to smokers, but Schelling's point does not depend on that. Even if we imagine that the nonsmoker is a visitor from a culture with different customs, if the nonsmoker is aware of the local norm, and if the smoker knows he or she is aware of the local norm (or merely assumes he or she is), the influence remains. The salience of precedent generates expectations that the smoker will not defer. Wishing to avoid unpleasant conflict, the nonsmoker defers.

Third-Party Expression Produces Salience

Precedent is not the only feature that makes a particular solution salient. Reference SchellingSchelling (1960) contended that third-party expression can make an outcome focal and thereby influence behavior. A third party can recommend or demand that the individuals coordinate in a particular way and create self-fulfilling expectations that the recommended or demanded behavior will occur.

In a pure coordination game, the influence of a third party seems obvious. As an example, Reference SchellingSchelling (1960) supposed that two people are accidentally separated from each other in a department store and face the coordination problem of finding each other. Schelling imagined that the department store owner has posted prominent signs through the store stating something like “Lost parties should reunite at the fountain on the first floor.” It is easy to imagine that this third-party expression influences the people's behavior. Even though the department store is not threatening to sanction anyone who fails to follow its advice and even if the two shoppers do not perceive the department store owner as a legitimate authority (or are in the store precisely to protest its illegitimacy in some dimension), the salience of the recommended meeting place gives them both a reason to go there.

But can third parties construct focal points in mixed games involving conflict as well as coordination? Schelling thought so and gave a compelling example in the traffic context, which we offer as a central metaphor for focal point power. Suppose that the traffic light fails at some busy intersection and a bystander—not a police officer—steps into the intersection to direct traffic. Schelling conjectured that the bystander's hand signals would influence the drivers' behavior. As two drivers approach from different streets, each prefers to proceed ahead of the other, though each regards the worst outcome as a collision. If the drivers can both see (and see that the other sees; in short, have “common knowledge” that) the bystander motioning one driver to stop and the other to proceed, then the driver who is told to stop will now have much more reason to fear that the other driver will proceed. Given that expectation, the best response is to stop, which is to comply with the third party's expression. Again, the third party appears to wield behavioral influence even without possessing legitimate authority and without threatening sanctions. Certainly, those two elements would likely increase the degree of compliance with the bystander's signals, but we should not predict the complete absence of compliance even if the bystander lacks any legitimate authority or sanctioning ability.

Law Is a Form of Third-Party Expression for Constructing Focal Points

Whether the source of law is a legislature, judicial opinion, or administrative agency, a legal rule expresses how to resolve a conflict. Law is therefore a form of “third-party expression” pointing to particular behavior resolving a dispute. If the dispute the law addresses includes an element of coordination, if the law is sufficiently clear and public, and if there are no other competing focal points, the state's public declaration of a legal rule should influence behavior by constructing a focal point. A number of theorists have posited that legal rules thus create the salience necessary to influence behavior in any mixed-motive situation (Reference CooterCooter 1998; Reference Garrett, Weingast, Goldstein and KeohaneGarrett & Weingast 1993; Reference Ginsburg and McAdamsGinsburg & McAdams 2004; Reference Hardin, Grofman and WittmanHardin 1989; Reference Hay and ShleiferHay & Shleifer 1998; Reference McAdams and NadlerMcAdams & Nadler 2005; Reference McAdamsMcAdams 2005; Reference PosnerPosner 2000). This final claim is what we tested in our contextualized experiments discussed below.

We note, however, that the necessary conditions for this effect do not always hold: law may address situations of pure conflict, where there is no element of coordination. Or even if there is an element of coordination, the publicity of the law often depends largely on media coverage, which does not always exist. Law cannot create a focal point if the content of the law is generally unknown. Even if publicized, the content of the law is often unclear, especially to nonlawyers. Law cannot align expectations unless it is sufficiently clear that most individuals have the same interpretation of it. Finally, even if the law enjoys clarity, it may face competition from factors that make another outcome salient. Most commonly, the law may attempt to change an existing norm that, as precedent for past behavior, continues to make salient the behavior that adheres to the norm.

Nevertheless, the necessary conditions sometimes do hold. Indeed, we might see law as being the form of third-party expression for which these conditions are most likely to hold. First, law addresses disputes, which, as we explained above, often contain an element of coordination (when each side often regards the worst outcome as some form of destructive conflict). Second, there is often great publicity about legal rules from either media coverage or direct government advertising (as by public service announcements or the posting of signs). Third, though many laws are opaque, some are fairly simple, e.g., the right-of-way goes to the driver with the green light, or no smoking in restaurants. Finally, law often avoids having to compete with other stronger focal points, as where expectations are not fully settled.

Thus, to test the focal effect of law in the two experiments described below, we created narratives that involved a dispute containing an element of coordination with clearly stated legally proscribed outcomes and no competing focal point. As we describe in detail below, in this context we found strong evidence that law exerts a focal influence on behavior.

Experiment 1: The Cat Dispute

Background: The Hawk/Dove Game

So far, we have described a class of mixed-motive interactions but not identified any specific games. Of many possibilities, we use the Hawk/Dove (HD) game as a means of modeling a property dispute. In this game, each person chooses between an aggressive strategy—here, to insist on disputed property (“Hawk”)—and a passive strategy—to yield to the other claimant (“Dove”). In HD, each person most prefers playing Hawk against the other person's Dove; at the same time, each person least prefers playing Hawk against the other person's Hawk. In fact, if a person expects the other person to play Hawk, then the first person prefers to play Dove in response. Translated into the property example, each claimant would most prefer to use the land as he or she wishes while the other claimant acquiesces. But if the first claimant knows that the second one will choose to insist, then the first would prefer to defer rather than have a fight.

We illustrate these situations with the 2 × 2 table in Figure 1. Each box represents the outcome that will result for both individuals depending on the strategies they (simultaneously) choose. For each of the four outcomes, we list a “payoff” for Individual 1 in the lower left corner and a payoff for Individual 2 in the upper right corner. The particular numbers are not important, but their relative size captures the basic structure of the interaction, which is that, for each individual: the best outcome is to play Hawk against the other's Dove; the second best outcome is to play Dove against the other's Dove; third best is to play Dove against Hawk; and worst is to play Hawk against Hawk. So the two individuals have conflicting interests over the choice between Hawk/Dove or Dove/Hawk (each also preferring one of these to Dove/Dove), but a common interest in avoiding Hawk/Hawk.

Figure 1. A Hawk/Dove Game

We set out to answer the question of whether the forms of third-party expression used in our previous work (i.e., spinner, randomly selected leader, and leader selected via merit; Reference McAdams and NadlerMcAdams & Nadler 2005) really model law. In the first experiment reported here, we embedded the HD game into a vignette about a dispute, rather than using the context-less 2 × 2 normal form game as we did in our previous study. Specifically, participants imagined themselves in a property dispute about a cat, which was carefully structured— in both the qualitative description and the quantitative payoffs—as an HD game.

We started from the premise that in a mixed-motive coordination game such as HD, when the law makes one outcome salient to disputants, it influences disputants to choose that outcome for a number of possible reasons, including: (1) fear of sanctions; (2) perceived legitimacy of law; and (3) law's ability to create a focal point in a coordination situation involving multiple equilibria. In our previous work involving a stylized normal form game (Reference McAdams and NadlerMcAdams & Nadler 2005), we were able to separate out the effect of sanctions and legitimacy from the focal point effect. We partitioned out the effect of sanctions simply by imposing no penalty or change in payoffs as a result of failure to comply with the third-party expression. We partitioned out the effect of perceived legitimacy of the law by simply not invoking law or legal processes at all in the third-party expression. Instead, the third-party expression took the form of a leader (either randomly selected or selected via a process involving merit) or of an explicitly random spinner.

When the game is embedded in a social context, separating out the effects of sanctions is still easy. We merely hold constant the payoffs in the game, so there is no greater loss from any failure to comply with the third-party expression. Partitioning out the effect of legitimacy, however, is extremely difficult once any mention of “law” is made. To solve this problem, in this study we used as a comparison a single-equilibrium game (a one-shot PD game), where legitimacy may operate but law does not function as a focal point because there is only one equilibrium (because each player selects the one strategy that is best no matter what strategy the other selects). We thus compared the effect of law in a single-equilibrium PD game with the effect of law in a multiple-equilibrium HD game, where both legitimacy and the focal point effect might operate simultaneously. By comparing the joint effect of legitimacy and focal point in HD to the sole effect of legitimacy in PD, we can estimate the magnitude of the focal point effect.

Design

In the experiment, participants imagined themselves in a dispute about ownership of a cat. Each disputant simultaneously made a decision about whether to insist on owning the cat (“Insist”) or defer to the other disputant's claim to the cat (“Give In”). We manipulated the effect of law by telling participants that the law favors the other (imagined) party or by mentioning nothing of the law. The No Law condition therefore serves as a baseline measure of the participant's likelihood of Giving In to the other party's claim to the cat. Therefore, if law influences the participant's decision, it should have the effect of decreasing the likelihood that the participant will Insist on his or her claim to the cat. At the same time, we partitioned out the effects of legitimacy of law by a difference-in-differences approach: comparing the effect of law in HD with the effect of law in PD, as described earlier. If the law influences behavior by functioning as a focal point, we would expect to observe a stronger effect of law in HD (attributable to both legitimacy and the focal point effect) than in PD (attributable only to perceived legitimacy).

We measure the effect of law by the rate of Insisting. In this experiment, when law is mentioned, it says that the other disputant is the rightful owner. Therefore, the strategy consistent with the requirements of the law is to Give In to the claim of the other party; conversely, the strategy inconsistent with law is to Insist. We can compute the effect of legitimacy (L) by subtracting the rate of Insisting in the PD game where there is law (I pdl) from the rate of Insisting in the PD game where there is no law (I pdn), as follows:

We can then compute the effect of the focal point (F) by subtracting the effect of legitimacy from the difference in rates of compliance between Law (I hdl) and No Law (I hdn) in the HD game as follows:

Thus the extent to which the effect of law is greater in HD than in PD is the extent to which the law functions as a focal point to coordinate behavior.

Participants

Participants were invited to participate via an e-mail message sent to individuals who had previously registered as a volunteer to participate in Web-based research.Footnote 1 The e-mail message included a URL for a survey hosted on the Internet. Participants were offered an incentive for participation in the form of a random draw to receive a gift certificate from an online retailer. Participants were assured that their responses would remain anonymous and that identifying information would not be collected.

An e-mail message was sent to 3,200 people, inviting them to participate. Of these, 271 messages were returned as undeliverable, leaving 2,929 valid addresses remaining. Of these, 490 people completed the survey. Toward the beginning of the survey, three questions were designed to test basic understanding of the materials; 129 people failed to correctly answer at least one of these three questions, so their responses were excluded from the results, leaving a final sample size of 361. Of these, 65 percent were female, and 89 percent were white. The participants' mean age was 40 years.Footnote 2

Materials and Procedure

This experiment had a 2 (Game: HD, PD) × 2 (Focal Point: Law, No Law) between-subjects design. Participants read a vignette in which they imagined themselves involved in a property dispute. Afterward, they made a decision about which strategy they would use in the dispute: Insist or Give In. After making their decision about the dispute, participants answered a question regarding their reason for their decision.

In designing the experiment, we faced a difficulty. We wanted to motivate the subjects by creating a high-stakes dispute where neither party would resort to the courts (so that the legal rule would not matter as a prediction for what outcome a court would compel via legal sanctions). If, however, the apparent stakes were high in monetary terms then it might seem implausible that neither party would resort to the courts. We therefore sought to create a dispute over something valuable in nonmonetary terms, so our vignette involved a pet. Participants read a story involving a dispute over ownership of a cat. In the vignette, we asked the participant to imagine that he or she adopted a young kitten (“Whiskers”) but that soon another person (“Morgan”) innocently came into possession of the same cat (renamed “Boots”) by purchasing it at the local farmer's market after it had been stolen. Each party (the participant and Morgan) maintains that he or she is the rightful owner of the cat. The cat is now being cared for by a neutral third party (“Francis”), who has given the disputants a limited amount of time to simultaneously make a decision about the final disposition of the cat. At the conclusion of the vignette, the participant must choose between insisting on possession of the cat or deferring to Morgan's claim of the cat. Participants are informed that Morgan must simultaneously make the same decision.

In the No Law condition, we told participants that the courts in their state have never decided who would own the cat in this kind of circumstance and that no one knows how the courts would decide the issue. In the Law condition, participants learned that both parties know for certain that the law (based on an old court case) says that Morgan now owns the cat because Morgan purchased it in good faith not knowing it had been stolen. However, the cost of a lawsuit, even in small claims court, is far too expensive for both parties. In both the Law and No Law conditions, participants are informed that the police and courts will take no action regarding this dispute.

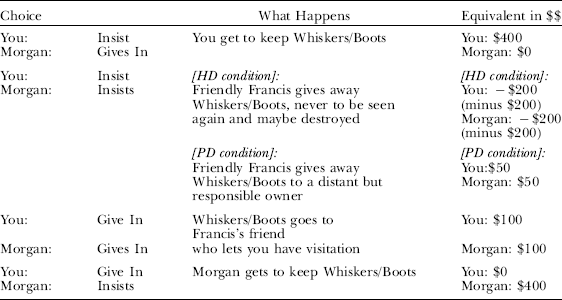

Prior to participants making a decision, we informed them of the consequences of each combination of options available to them and to Morgan. We gave the information in two formats: narrative and monetary. The narrative information was the text of the vignette; an accompanying table summarized the monetary consequences. We explained the monetary consequences as follows:

Both of you must decide simultaneously, by writing down your final decision—Insist or Give In—without knowing what the other's decision will be. After that the results indicated below will occur. Because you and Morgan love the cat so much, neither could really place a dollar value on how much the cat means to you. Nevertheless, if forced to place a valuation on the consequences of their [sic] choices, you would do it like this:

Participants saw the table shown in Table 1, except that the second row (You: Insist; Morgan: Insists) contained only one set of results, depending on whether the participant was assigned to the HD or PD condition (the labels in italics indicating condition were also omitted for participants). In the HD condition, the consequence of both parties Insisting is that Francis gives the cat to a shelter in a faraway, undisclosed location, where it will be adopted by an unknown person or possibly even destroyed. In the PD condition, the consequence of both parties Insisting is that Francis gives the cat to a responsible person in a faraway, undisclosed location.

Table 1. Description of Consequences Given to Participants in Experiment 1

It is important to note that both the narrative and monetary consequences are identical in the HD and PD game conditions with the exception of one combination of options—where both parties insist, as depicted in Table 1. This is the defining difference between the structure of the HD game and the structure of the PD game. In the PD game, the worst outcome for each party is when he or she decides to Give In and the other party decides to Insist; in this particular PD game, playing Give In against Insist results in $0. By contrast, the worst outcome in the HD game occurs when both parties play Insist, which in this HD game results in a loss of $200 for each party. As a result, in the PD game the best strategy is to Insist because, no matter what the counterpart does, Insists or Gives In, Insisting produces the higher payoff. By contrast, in the HD game, the best strategy depends on what the counterpart will do. If the counterpart will Insist, then one is better off Giving In. But if the counterpart will Give In, one is better off Insisting. Because of this, there are two pure-strategy equilibria in the HD game: (1) the first party Insists and the second Gives In, or (2) the first party Gives In and the second Insists.

As explained above, we hypothesized that the effect of Law would be greater in the HD game than in the PD game. Because the Law condition favors the other party, if a participant decided to make a decision based on the law, the participant would decide to Give In rather than Insist. Thus, we hypothesized that Law would cause the participants to Give In more frequently in the HD game than in the PD game.

Pilot Data

We wanted to ensure that respondents would perceive the payoff structures of the two games in the expected way. To explore this point, we collected data on the perceived structure of the verbal descriptions of the games in Table 1. Using a separate sample of 195 participants drawn from the same population as the main experiment, we randomly assigned pilot respondents to conditions as described above and presented each pilot respondent with the experimental materials, modified as follows. The description of consequences for the assigned game (either HD or PD) contained the verbal descriptions, but not the monetary equivalents depicted in Table 1. We asked each pilot respondent to rate the desirability of each outcome according to their own personal preference (1-Terrible; 7-Great).

Results indicated that, in the HD game, the outcome with the lowest mean rating was Insist/Insist (“You insist and Morgan insists,”M = 1.32), as we had intended. The outcome with the highest mean rating was Insist/Give In (“You insist and Morgan gives in,”M = 6.38), also as expected. Most crucially, the mean rating for Insist/Give In (“You insist and Morgan gives in,”M = 6.38) was significantly higher than the mean rating for Give In/Give In (“You give in and Morgan gives in,”M = 4.38), Wilcoxon signed-rank z = 6.77, p<0.001. Equally as crucial, the mean rating for Give In/Insist (“You give in and Morgan insists,”M = 2.74) was significantly greater than the mean rating for Insist/Insist (“You insist and Morgan insists,”M = 1.32), Wilcoxon signed-rank z=−7.07, p<0.001.

These responses ensure that the vast majority of respondents were playing the HD game we intended. The verbal descriptions given for HD are perceived by respondents in a way that correspond to the ordinal structure of the payoffs of the game. Respondents believe that their best decision depends on what they expect the other player to do, which is the situation where the focal effect can operate.

In the PD game, the outcome with the highest mean rating was Insist/Give In (“You insist and Morgan gives in,”M = 6.64), as expected. Crucially, Insist/Give In was rated significantly higher than Give In/Give In (M = 4.11), Wilcoxon sign-rank z = 7.22, p<0.001. Unexpectedly, Insist/Insist (“You insist and Morgan insists,”M = 2.18) and Give In/Insist (“You give in and Morgan insists,”M = 2.25) were ranked equally as the worst outcome, Wilcoxon sign-rank z=−0.53, p = 0.59. If a respondent expected Morgan to give in, then we intend that his or her best choice is to insist, and this is borne out in the perceptions of the verbal descriptions. If a respondent expected Morgan to insist, then we intend that his or her best choice is to insist; however, the perceptions of the verbal descriptions do not reflect this ordering as a clear preference for respondents.

Overall, with one exception, these results confirm that our respondents perceived our verbal descriptions in a way that corresponds to the ordinal structure of the payoffs of the game. One subset of responses indicates no clear preference, based on the verbal descriptions alone, regarding how to best respond to the opponent's decision to insist in PD. The presence of this subset of responses in the data means that the hypothesized effects will be more difficult to detect than if this subset were absent (i.e., the data will be more noisy). This difficulty is potentially offset (at least partially) by the relatively large sample size (N = 361) of Experiment 1. There is no reason to believe, however, that the presence of this subset of responses will bias the responses toward the hypothesized results; to the contrary, this ambiguity in the perception of the verbal descriptions may bias the results away from our hypothesis. This is because 21.8 percent of the pilot study respondents in the PD condition perceived the verbal descriptions in such a way as to create a multiple-equilibrium game. That is, members of this subgroup indicated that they would prefer to Give In if the other party Insisted, but at the same time would prefer to Insist if the other party gave in. These individuals needed to coordinate their actions and therefore experienced the PD condition not as an actual PD game, but as a game like HD, in which the law can influence behavior by creating a focal point. If some respondents in PD condition are influenced by the focal effect of law, that will reduce the difference we hope to find between legal compliance levels in the HD and PD conditions.

In short, the pilot data indicate that respondents perceived the verbal descriptions as accurately reflecting the underlying ordinal structure of the HD game. Perceptions of the verbal descriptions in the PD game are largely but not entirely as we intended; to the extent there is lack of clarity, however, it biases results away from our hypothesis. In Experiment 1, we coupled the verbal descriptions with the monetary equivalents to enforce the ordinal payoff definitions of PD and HD, respectively. We theorized that appending the monetary equivalents to the verbal descriptions would help reinforce the intended ordinal structure of the PD game.

Results

Effect of Game and Focal Point on Insist Rate

Our primary dependent measure was the rate of Insisting, which we predicted would decrease as the effect of law increased. We first tested the effect of law on the likelihood of Insisting in the PD game. Any difference in the Law and No Law observed here would be attributable to the perceived legitimacy of law. In fact, the mean Insist rate between participants in the Law and No Law conditions in the PD game was virtually identical (64 versus 66 percent), and not surprisingly, this comparison is not statistically significant (χ2(1) = 0.041; p = 0.84). By contrast, there was a significant difference in the mean Insist rate between participants in the Law (27 percent) and No Law (44 percent) conditions playing the HD game; this difference is statistically significant (χ2(1) = 5.62; p<0.05). Figure 2 depicts these differences. Though there appears to have been no effect derived from the perceived legitimacy of law,Footnote 3 the results suggest that the focal point effect of law reduced the Insist rate from 44 to 27 percent. We ran a logistic regression analysis, where the binary dependent variable was Insist/Give In. The main effect of Game (HD, PD) was statistically significant (Wald χ2(1) = 31.9; p<0.001), but the main effect of Law (Wald χ2(1) = 3.37; p = 0.066) and the interaction term (Game × Law) (Wald χ2(1) = 2.42; p = 0.12) fell shy of conventional levels of statistical significance, despite the clear pattern that emerges in the chart in Figure 3. We attribute this failure to detect these differences to insufficient statistical power required by the logistic regression model.

Figure 2. Percent Insisting by Game and Focal Point, Experiment 1

Figure 3. Percent Insisting by Reasoning, Game, and Focal Point, Experiment 1

Reasons for Decision

Participants were also asked to choose one from among the following reasons for why they chose to Insist or Give In. These were:

“I made the choice that I thought was deserved” [deserved]

“I made a rational calculation about the choice that was most likely to result in the best outcome” [best outcome]

“I felt I needed to do what was best for Boots/Whiskers” [best for cat]

“None of the above comes close to describing my reasons” [none of the above]

The results are illustrated in Figure 3. Note that participants who said that they tried to rationally calculate the best outcome overall (N = 83) did exactly as we predicted, in that the difference between Law and No Law is bigger in HD than in PD (in the second column labeled “best outcome”). Participants who said their decision was based on placing the cat's interests first (N = 143) also did exactly as we predicted, in that Law reduced the Insist rate in HD more than it did in PD (depicted in the third column, labeled “best for cat”). Among these respondents, the lowest mean insist rate by far was among respondents who reported placing the cat's interest first who were in the HD/Law condition, where there was a possibility that the cat could be destroyed. In HD for this subgroup, Law apparently made the focal point of Participant-Give In/Morgan Insist more salient than in the No Law condition. We take this as a vindication of the theory because it demonstrates that the focal effect is most clear when the costs of “fighting” are high. Recall that we selected a cat because we wanted subjects to perceive simultaneously that there was much at stake even though the parties would not resort to the courts. There was, however, a risk that some subjects would not care much about cats. That the same results emerged in this subgroup of respondents provides good evidence for the theory.

Consider next the participants who said they made their decision based on what was deserved (N = 97). Remarkably, these participants appear to have paid virtually no attention to law at all, and were unmoved by the dire consequences (for the cat) of the Hawk-Hawk outcome in the HD game. Those moved by desert/fairness appear to have simply chosen Insist no matter what because they thought they deserved the cat (i.e., they owned it first, etc.). For this group, it appears that law can influence their behavior, if at all, only through legal sanctions and/or legal legitimacy.

The “Other” category (N = 38) is more difficult to interpret because the cell sizes are very small (N ranges from 2 to 15 in each of these four cells). It appears, however, that this group also behaves as predicted but it is impossible to say why, given that we have little information about their self-reported reasoning.

Experiment 2: The Contract Dispute

We conducted a second experiment because we sought to replicate the findings of the first experiment and to establish the generality of the findings along several dimensions: the factual context, the legal context, and the game context. First, we wished to show that the results generalize outside of the factual context of one particular dispute about a cat. In the second experiment, we used the context of a commercial transaction. Second, by moving to a commercial transaction we also changed the legal context, moving not only from property to contract, but also from a context where law provides a mandatory rule (of ownership) to a context where law supplies merely a default rule (of contract damages). Finally, we changed the game context, moving from an HD game to a Battle of the Sexes (“BOS”) game, as described below. In so doing, we seek to show that law can work expressively by creating a focal point in any situation in which it is important to coordinate with the other party.

The particular HD game we used in Experiment 1 is merely one strategic situation in which it is extremely useful to be able to predict what the other party is going to do, so as to coordinate one's behavior with the other. Another such situation is the so-called BOS game, which we employed in the second experiment to test the focal point theory of expressive law. BOS is named after an early illustration in which a couple wants to go out together, each has a different preference about where to go, and both would rather go to the same place than different ones. This game models any situation in which each player values coordinating, but each player prefers a way of coordinating that is different from that favored by the other. Such conflict arises in certain disputes, specifically those in which there is no realistic possibility of a settlement that divides the gains or losses equally between the parties. For example, two siblings may dispute over ownership of a family heirloom, where time-sharing is impractical and neither can afford a side payment to the other that equalizes the gain. Or divorcing parents may each prefer to obtain custody over their child in circumstances where equal joint custody is logistically unworkable. Law often addresses such cases.

In Experiment 2, we designed a hypothetical contract negotiation so that in one condition it had the structure of BOS. In this situation, each party has a different preference for a damages remedy—one prefers a profit remedy and one prefers an out-of-pocket loss remedy. However, like the couple who is trying to coordinate going on a date, each party to the contract dispute prefers to coordinate on some remedy, rather than having the negotiations break down and ending up with no contract at all.

We hypothesized that even the weakest kind of law—a default rule—could work as a focal point. A default rule merely states the rule that will control if the parties to the contract do not specify a different rule in their agreement. By definition then, default rules are not binding and impose no sanctions. Nonetheless, an experimental literature finds that default rules influence the behavior of negotiating parties in that the party favored by the default rule tends to gain more of the available contractual surplus (see Reference KorobkinKorobkin 1998a:1626–7, Reference Korobkin1998b:675–6; Reference SchwabSchwab 1988:254–6). The influence of default rules on behavior in contractual negotiations is partly a manifestation of the endowment effect—generally, people are reluctant to part with commodities they own (Reference KahnemanKahneman et al. 1991; Reference Rachlinski and JourdenRachlinski & Jourden 1998). Legitimacy theories might also explain this effect, but we nonetheless reasoned that a default rule, by pointing to a particular outcome, could influence behavior independent of legitimacy (or endowment) by creating a focal point that would help each party predict what the other would do. Our hypothesis, then, differed from the more general prediction derived from the endowment effect and the status quo bias, which would posit that people show a general preference for contract default rules, regardless of the structure of the underlying game. By contrast, we predicted that the preference for contract default rules will be strongest in a situation involving coordination, because the default rule will make focal one remedy around which parties can coordinate.

For example, suppose that contract law allows the parties to specify a remedy, but the default remedy is lost profits (“the profit remedy”). In this case, the party who prefers the profit remedy is happy to stick with the default rule. The party who prefers an out-of-pocket remedy is not so happy with the default rule but must take into consideration that the other party might be more likely to insist on a profit remedy simply because the profit remedy is also the default rule. In the experiment, we intentionally (and somewhat artificially) set up the situation so that after an exhausting period of negotiation, the parties have agreed that they must simultaneously and independently indicate a single remedy that they require to be incorporated into the contract. If their decisions match, they have a contract. If their decisions do not match, there is no contract. We hypothesized that the presence of a default rule can act as a focal point to help parties coordinate on a contract.

The design of Experiment 2 is therefore much like that of Experiment 1, with one key difference. As in the first experiment, we used a PD game as a control, because (in its one-shot form) it has only one pure-strategy equilibrium and therefore does not give rise to the opportunity to coordinate behavior. As in the first experiment, we then compared the results of the PD game with the results from a game involving coordination. The effect of the law's legitimacy (and endowment effect) should arise in the PD game; we could then attribute any additional compliance in the coordination situation to the focal point effect. The one difference from Experiment 1 is that the coordination game there was HD, whereas here it was BOS. In Experiment 1, our main result was to show that the strategy suggested by law was followed more in the coordination game than in the PD game, which we attribute to law's focal effect. In Experiment 2, with a similar design, we also predicted that law will have a greater influence in the coordination game, compared to the PD game.

Participants and Design

Participants were invited to participate via an e-mail message sent to law students enrolled at a law school in the midwestern United States. The e-mail message included a URL to a survey hosted on the Internet. Participants were assured that their responses would remain anonymous.

Ninety-two participants completed the survey. We did not collect demographic data (e.g., age, sex) in this experiment. The experimental design was identical to that of the first experiment, except that the game of interest was BOS rather than HD. Specifically, this experiment had a 2 (Game: BOS, PD) × 2 (Focal Point: Law, No Law) between-subjects design. Participants read a vignette in which they imagined themselves involved in a contract negotiation. Afterward, they made a decision about which strategy they would use in the dispute: Insist or Give In.

Materials and Procedure

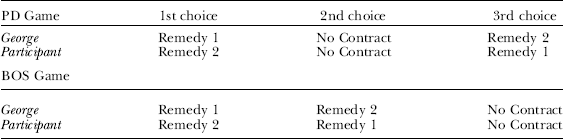

Participants read a story involving a contract negotiation. In the vignette, the participant was asked to imagine that he or she and the other party, George, have settled on all of the terms of the contract except for those defining the remedy in the event of breach. The parties have narrowed the possibilities to two possible remedy terms: (1) a profit remedy, in which the breaching party pays the other party the profit that the other would have made had the contract been performed; or (2) an out-of-pocket loss remedy, in which the breaching party pays the other party the out-of-pocket losses incurred as a result of entering into the contract.

Participants learned that the parties have been negotiating for a long time and have agreed to all terms except for the remedy. In all conditions, the participant prefers Remedy 2 (out of pocket) but George prefers Remedy 1 (profit). In the No Law condition, the law allows parties to specify either remedy, but if the parties disagree over the remedy, they will have no contract.Footnote 4 By contrast, in the Law condition, the law allows parties to specify either remedy, but if they reach agreement on all terms without specifying a remedy (and without agreeing in negotiations not to have a contract unless they agree to a remedy), then the default rule will supply the remedy term; in this jurisdiction, the default rule provides for Remedy 1 (profit).

In the BOS condition, participants were told that even though their first choice is Remedy 2, they would much rather have a contract with Remedy 1 than have no contract at all. Similarly, they were told that even though George's first choice is Remedy 1, he would rather have a contract with Remedy 2 than no contract at all. This structure of preferences creates a BOS game where one's best choice depends on what the other party's choice is, and there are two equilibria (each is a contract with a different remedy provision).

In the PD condition, participants were told that while their first choice is Remedy 2, they would rather have no contract than a contract with Remedy 1. Similarly they were told that George's first choice is Remedy 1 but that he would rather have no contract than a contract with Remedy 2. This structure of preferences creates a PD game, where one's best choice is to Insist on one's preferred remedy no matter what the other party does (and the only equilibrium is no contract). Participants in both conditions were informed that each party knows all the information. This information is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Party Preferences Regarding Remedies, Experiment 2

Participants were therefore randomly assigned to one of the four following conditions: BOS/No Law, BOS/Law, PD/No Law, or PD/Law. After being informed of the law and the parties' preferences, participants were told that neither party wants to leave the contract silent on the remedy issue, that both are tired of negotiating, and that both parties have decided to limit further efforts to reach a contract. There will be one last round of negotiations during which each party will simultaneously place in an envelope the final breach remedy proposal, without seeing what the other is doing. If both propose Remedy 1 then there will be a contract with Remedy 1; if both propose Remedy 2 then there will be a contract with Remedy 2; if one party proposes Remedy 1 and the other party proposes Remedy 2, there is no contract.

Similar to the first experiment, we hypothesized that the effect of Law would be greater in BOS than in PD. Because the Law condition favors the other party, if Law influenced a participant's decision, he or she would be more likely to select the nonpreferred Remedy 1 (profit). Thus, we hypothesized that Law would cause the participants to select Remedy 1 more frequently in the BOS game than in the PD game. Because the narrative presents simple ordered preferences, ranking the three possible outcomes, we saw no need to test separately whether the participants interpreted the game as we indicated.

Results

As in the first experiment, the dependent measure of interest was the percentage of respondents who Insisted on their preferred outcome (here, Remedy 2). A logistic regression analysis showed a significant Game × Law interaction (Wald χ2(1) = 4.41; p<0.05). We first tested the effect of law on the likelihood of Insisting in the PD game. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean Insist rate between participants in the Law and No Law conditions in the PD game: 90 percent of participants in the No Law (PD) condition Insisted on Remedy 2, and 78 percent of participants in the Law (PD) condition insisted on Remedy 2 (χ2(1) = 1.35; p = 0.25).Footnote 5 By contrast, there was a statistically significant difference in the mean Insist rate between participants in the Law (42 percent) and No Law (72 percent) conditions playing the BOS game (χ2(1) = 3.99; p>0.05). This pattern is depicted in Figure 4. Thus, we were able to confirm in Experiment 2 our main findings that law acted as a focal point to influence behavior in a game involving coordination (here, BOS) but not in a PD involving no coordination.

Figure 4. Percent Insisting by Game and Focal Point, Experiment 2

Summary and Discussion

In these experiments, we have extended our earlier findings that nonbinding third-party expression such as law can influence behavior merely by making one behavioral outcome salient. We sought to test directly and specifically the effect of legal rules in highly contextualized narrative vignettes, rather than the general effect of third-party expression in the abstract strategic setting used previously. Between the two experiments we report here we varied the contexts in three ways to test the robustness of the focal effect, using different factual settings, different legal settings, and different strategic (game) settings. The first experiment involved a property dispute concerning a cat, where we compared the effect of a mandatory legal rule on behavior in a HD and PD game. The second involved a contract negotiation where we compared the effect of a default rule on behavior in a BOS and PD game. Each experiment confirms that legal rules can create a focal point around which people tend to coordinate in a mixed-motive coordination game.

For each experiment, the key to identifying a novel influence of law was to control for the influences already well established in the literature: the role of sanctions and legitimacy. In Experiment 1, we excluded the effect of sanctions by explaining in the narrative that, given the nature of the dispute, neither side would resort to the courts and the police would not get involved; in addition, we showed the subjects payoffs that did not vary between the Law and No Law conditions. In Experiment 2, we excluded the effect of sanctions by using default rules, which impose no sanctions because the parties are free to change the rule.

The more complex methodological challenge was to control for the effect of legal legitimacy. Here, we used a difference-in-differences approach. Because focal point theory applies only in situations requiring coordination between multiple equilibria, we contrasted such settings—using HD and BOS games—with an otherwise identical setting with only one equilibrium and no need for coordination—a PD game. In each game setting, we compared behavior with and without law. We found that law has a greater effect in the HD and BOS settings than the PD setting—essentially, that the law's legitimacy plus focal effect is significantly greater than its legitimacy effect alone. Thus, despite the fact that there were no sanctions for ignoring the law in the dispute in which participants imagined themselves, the law made it more likely that they would defer to the other party's claim. Because the effect emerged only in the game in which law could function to provide a focal point, we can also rule out the contribution of legal legitimacy.

If our results are reliable, then there is one more way in which law may influence behavior: not only because people tend to defer to what they perceive as legitimate authority nor only because individuals are deterred (or incapacitated) by legal sanctions, nor only these two influences together, but also because law constructs a focal point in situations of coordination. Although it is difficult to isolate the focal point power in the field, given that law's salience is usually bound up with its legitimacy and sanctions, we do think the theory helps to understand the effect of certain laws in “everyday life” (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 1998; Reference Sarat and KearnsSarat & Kearns 1995). We illustrate the significance of the research presented here by returning to some of the examples we used to illustrate focal point theory.

Perhaps the most “everyday” example is traffic. However mundane this field of human interaction is, the annual deaths from automobile accidents—43,000 in the United States (NHTSA Report 2006) and more than 1 million worldwide (World Health Organization 2004)—demonstrate the importance of traffic regulation. Yet traffic is quintessentially a matter of coordination, where drivers usually prefer that everyone yield to them but nonetheless rank yielding to others as better than the collision that occurs when neither yields. For this reason, we think it would be a serious mistake to study compliance and noncompliance with the rules of the road without understanding the possibility of a focal point effect. Indeed, there is every reason to think that the government exploits the focal point effect for its traffic rules because (1) those rules are relatively clear, and (2) the government publicizes them by requiring driver's tests and by posting traffic signs. Thus, without denying the effect of sanctions and legitimacy, we conjecture that the focal effect is a significant cause of compliance with traffic laws, which is substantial despite obvious examples of violations (such as speeding). When a driver approaching a busy intersection observes a sign or traffic light indicating “stop” or “yield,” the driver has a strong reason to comply independent of sanctions and legitimacy.Footnote 6 Even if the driver has no fear of or respect for law, he or she fears an accident. Knowing that others expect the driver to comply, and that miscoordination entails a serious risk of collision, the driver's best choice is to comply.

Similarly, there is a pervasive element of coordination in the kind of disputes and negotiations more typically studied by law-and-society scholars (e.g., Reference MacaulayMacaulay 1963; Reference ErlangerErlanger et al. 1987; Reference EdelmanEdelman et al. 1993). All that is necessary (among other possibilities) is that the parties involved in a dispute jointly regard some outcome as the worst result. If so, then while the existence of the dispute means there is genuine conflict, there is also a common desire to avoid some mutually bad outcome. Two people who contest ownership or use of property may each regard violence as the worst outcome, worse even than giving in to the other's claim. A smoker and a nonsmoker may each regard a profane shouting match as the worst outcome of their conflict over smoking. Two groups of union members may dispute over whether to strike but jointly regard the worst outcome as internal disunity that weakens their power against management. In each case of disputing and negotiating, the law may influence the behavior in part merely by pointing to a particular resolution and thereby making that outcome focal. Expecting the party favored by the focal point to insist, the other party is more likely to defer.

Finally, consider international law and relations. Suppose two nations conflict over trade barriers or territorial claims because they most prefer different outcomes. Yet even though they may each attempt to bluff the other into believing otherwise, each state may regard a trade war or shooting war as the worst possible outcome, in which case their conflict has an element of coordination. Given the absence of a centralized enforcer, there is frequently no credible threat of sanctions backing up international law, yet legal rules and pronouncements may still influence the parties by making salient one particular resolution of the conflict (Reference Garrett, Weingast, Goldstein and KeohaneGarrett & Weingast 1993). Reference Ginsburg and McAdamsGinsburg and McAdams (2004) found that compliance with decisions of the International Court of Justice is most likely in cases requiring coordination for which the court wields the focal point power. That “soft law” (Reference Abbott and SnidalAbbott & Snidal 2000) frequently influences states and private actors should also be no surprise if the causal mechanism is focal power.

Thus far we have considered focal points created by law. But nonlegal actors also construct focal points in ways that remain highly relevant to legal studies. We begin by noting that law is not merely a means of resolving disputes; it supplies another means of disputing. What is true of violence, shouting matches, and organizational disunity is often true of litigation—that a lawsuit is so costly to each side that both regard it as the worst outcome (Reference KritzerKritzer 1991). Not always, of course—sometimes the worst outcome is giving in to the other side—but sometimes. Two divorcing parents who each seek primary custody of a child may regard the worst outcome as depleting savings intended for the child's college tuition by litigating over custody. An employer may regard protracted litigation as worse than rehiring the employee who claims to have been fired illegally, while the employee may regard such litigation (and the resulting reputation of being a troublemaker) as worse than giving up and seeking a new job (e.g., Reference BumillerBumiller 1988). Members of a school board may regard expensive litigation over a Free Exercise or Establishment Clause claim as worse than giving up the challenged practice, while the plaintiff may regard expensive litigation as even worse than living with what he or she regards as a constitutional rights violation (e.g., Reference DolbeareDolbeare 1971; Reference MuirMuir 1967). In every case, each side would most prefer that the other side give in and therefore to get one's way without expensive litigation. But because protracted litigation is the worst outcome, each side will try to convince the other to be the first to give in, but each will also prefer to give in if he or she becomes convinced that the other side will not.

Where this situation occurs, one possible result is the frequently observed “gap” in the law-on-the-books and the law-in-action (e.g., Reference BumillerBumiller 1988; Reference MuirMuir 1967; Reference RosenbergRosenberg 1991). Formal law may grant an individual or group some right, but if the litigation necessary to vindicate the right is too costly, the party entitled to prevail will regard protracted litigation as the worst possible outcome. Even if the defendant who should lose under the law also regards expensive litigation as the worst possible outcome, there is no certainty that the defendant will back down. Indeed, if a new law is meant to change the existing equilibrium behavior, but each side regards litigation as sufficiently costly, then the status quo behavior may remain the obvious focal point, meaning that the law fails to change behavior. If a new law nonetheless does change behavior, the reason may be that the social movement that changed the law also created a focal point extra-legally around the new behavior, causing prospective plaintiffs to act aggressively in asserting their claim and for prospective defendants to expect as much. As we stated at the outset of this article, the focal point theory says that any expression may construct a focal point; while we apply the theory to legal expression, it also applies to the expression of social movement leaders (and resistors) whose actions may then determine the effect of the law. Thus, we make no special claim for law, merely that the existing literature has overlooked that it is one means among many for directly (i.e., without changing payoffs or wielding legitimacy) influencing expectations in situations of coordination. Yet our findings may also shed light on the success of social movements where nonlegal actors wield the same expressive power.

Future Research

Future studies might examine certain factors held constant in our experiments, to gain a better understanding of the boundary conditions of the focal point effect. For example, one might introduce a context with strong legal legitimacy to see if a focal point would still have an independent effect. Second, in the two experiments reported here, we incorporated simultaneous decisions into the scenarios so that we could clearly demonstrate the ability of law to function as a focal point. Future studies might consider the messier but more common situation where parties do not make exactly simultaneous decisions, as in the dynamic setting of negotiating in the shadow of the law.

We have noted that it is difficult to test the focal point claim in the field, especially to gather the initial evidence needed to satisfy the skeptic. Yet if one takes our experiments as sufficient to make the claim empirically plausible, we believe that qualitative field research is also possible. Ethnographers may find the theory illuminating and also be able to contribute additional evidence. If individuals engaged in real-world disputes or negotiations reveal that they prefer “giving in” over the nonagreement or conflict that results when neither party gives in, then the researcher has identified a situation involving coordination. If these same individuals believe that the other party will act in accordance with law (either not giving in because the law is in their favor or giving in because the law is against them), then the researcher can investigate whether the focal point contributes to the expectation of compliance. The most obvious case is whether one can rule out other explanations: not sanctions if there is no fear of sanctions, and not legitimacy if the influenced party does not appear to understand the law as being legitimate or authoritative. At the least, the focal point theory cautions against too quickly equating legal influence with legal legitimacy. Finally, those in the field may test the idea that, where litigation is too expensive a means of disputing, the actual effect of a law depends on the related focal points created by social movement leaders and resistors.