Whey protein provides amino acids that are used mainly during the synthesis of glutamine in muscles: branched-chain amino acids (26 %) and glutamate (6 %)( Reference Cruzat, Krause and Newsholme 1 ). Therefore, these amino acids can be used to preserve muscular glutamine stock, which is widely required by immune system cells as an energy source in clinical states( Reference Newsholme and Parry-Billings 2 , Reference Newsholme 3 ) and during exercise( Reference Newsholme and Calder 4 , Reference Rohde, MacLean and Pedersen 5 ). There is evidence that glutamine has an important role in the maintenance of intestinal barrier function( Reference Wang, Wu and Zhou 6 ), which is also negatively regulated by prolonged and intense physical exercise, reducing intestinal absorption capacity( Reference Clark and Mach 7 ).

Physical exercise alters the immune system and cell function( Reference Clark and Mach 7 ). Therefore, intense exercise can increase the incidence of infections in the gastrointestinal tract and upper respiratory tract( Reference Nieman 8 ). These physiological changes are related to modifications of structural proteins known as tight junctions. These proteins remodel because of constant changes in blood flow in the intestinal region( Reference van Wijck, Lenaerts and van Loon 9 ). The joint action of epithelial cells and lymphoid tissue associated with the intestine and luminal bacteria can prevent pathogen invasion, thereby exerting an important barrier function( Reference Lamprecht and Frauwallner 10 ). Transmembrane proteins have been identified on tight junctions, where they regulate the immune system, water and solute paracellular permeability( Reference Garcia-Hernandez, Quiros and Nusrat 11 , Reference Fanning, Mitic and Anderson 12 ). Two of these proteins have been extensively studied in animal models: zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), a cellular adhesion protein responsible for signal transduction in cell–cell junctions, and claudin-1, an integral membrane protein that forms a paracellular barrier, playing an important role regulating epithelial cell permeability( Reference Fanning, Mitic and Anderson 12 , Reference Gunzel and Yu 13 ).

Probiotic supplementation of athletes can help reduce the frequency, severity and duration of gastrointestinal problems, as well as of respiratory illness. This occurs probably because of the direct interaction between these cultures, intestinal microbiota and the immune system( Reference Pyne, West and Cox 14 ).

Furthermore, intense or strenuous exercise can lead to an imbalance of reactive oxygen species production and the endogenous antioxidant system, resulting in oxidative stress( Reference Fuster-Munoz, Roche and Funes 15 ). Multiple studies have reported an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory action for pomegranate (Punica granatum, L.), which is associated with the presence of phenolic compounds, mainly gallic acid( Reference Gracious Ross, Selvasubramanian and Jayasundar 16 – Reference Sharma, McClees and Afaq 18 ).

Therefore, here we aimed to evaluate the effect of supplementation with fermented milk containing whey protein, probiotic and pomegranate juice on the physical performance, intestinal microbiota and motility, intestinal villi structure and inflammatory markers of rats submitted to high-intensity acute exercise.

Methods

Fermented milk production

The fermented milk was composed of skimmed powder milk (Molico®), concentrated whey protein (Alibra®, approximately 80 % de protein), maltodextrin (SweetMix®), fructose (Lowçucar®), pomegranate juice (var. Wonderful, obtained by fruit processing with industrial fruit pulper, model DPT-75; Tomasi®), potassium sorbate (SweetMix®), starter culture Streptococcus thermophilus (TA 072) and probiotic Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis (BB12), kindly provided by Danisco and Chr-Hansen, respectively. The fermentation was carried out at 42°C on Biochemical Oxygen Demand (model TE-371; Tecnal®) until pH 4·6±0·1.

Protein content

The protein content of the fermented milk was determined by the Micro–Kjeldahl method, applying a conversion factor of 6·38( Reference Drochioiu, Ciobanu and Bancila 19 ).

Probiotic viability on the fermented milk

The viability of B. animalis subsp. lactis (BB12) was evaluated in the fermented milk at 0, 14 and 28 d after production, using TOS-MUP media and incubation under anaerobiosis (AnaeroGen; Oxoid®) at 37°C for 72 h.

Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and blood serum

Determination of total phenolic content from pomegranate juice was performed using the Folin–Ciocalteau method, as described by Musci & Yao( Reference Musci and Yao 20 ).

The ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) method was used to evaluate the antioxidant activity. In brief, samples of pomegranate juice extract were placed in a ninety-six-well plate: 20 µl of sample, standard or water (blank); 30 µl of distilled water; and 200 µl of FRAP reagent, according to the method described by Benzie & Strain( Reference Benzie and Strain 21 ). Next, the plate was agitated and incubated at 37°C for 8 min, and the absorbance was read at 595 nm using a spectrophotometer (BioTek, EPOCH/2 microplate reader with Gen5.3.03 software version). The antioxidant activity of rat blood serum was also evaluated using the FRAP method. Animal blood was collected and centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min (centrifuge model K241R; Centurion Scientific®), and the supernatant was taken for analysis.

Ethics declaration

This work was approved by the Animal Use Ethics Committee (CEUA) of University of Campinas (protocol 4150-1) and was conducted under the ethics standards for animal experimentation of the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA).

Experimental groups

In all, twenty-four 10-week-old male Wistar rats weighing approximately 350 g (at the beginning of the experiment) were maintained in the Central Biotery from the School of Applied Sciences (FCA-UNICAMP). The rats were kept in polyethene cages, four animals per unit, at a controlled temperature of 25°C and 12 h light–12 h dark cycles, receiving potable water and standard commercial diet (Nuvilab®), ad libitum.

Rats were distributed among four groups: (i) the control (Ctrl) group, without supplementation and with no exercise; (ii) the supplemented group (Supp), with supplementation and with no exercise; (iii) the only exercised (Exe) group, without supplementation but exercised on a treadmill; and (iv) the supplemented plus exercised group (Exe+Supp), supplemented with the fermented milk and exercised on a treadmill.

During the experimental period, the weights of the animals were measured weekly using stabilised semi-analytical scales (model UX620H; Marte Científica®). A period of 12 h after an acute exercise session, the rats were anaesthetised with an intraperitoneal injection containing a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride and diazepam (70:30; 50 mg/kg) and then euthanised. Colon and faeces samples were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C. Distal colon samples were frozen in isopentane cooled in liquid N2 for further histological, immunofluorescence and PCR analysis. Blood samples were collected to obtain serum.

Supplementation with the fermented milk

The composition of the fermented milk was calculated on the basis of the appropriate amount of whey protein (20 g/d of protein), as proposed by Witard et al.( Reference Witard, Jackman and Breen 22 ). Each animal received 2 ml of fermented milk, 5 d/week, containing 8·9 (sd 0·3) log colony-forming units (CFU) of B. animalis BB12, whey protein (calculated according to animal average weight, measured weekly) and pomegranate juice with a concentration of 2·625 mmol of total polyphenols.

Acute exercise protocol

The rats were previously adapted on a rodent-motorised treadmill with electric shock stimulation (AVS Projetos®) for 1 week (for 10 min/d at 3 m/min). Then, rats performed the incremental load test (ILT) with an initial intensity of 6 m/min at 0 % with increasing increments of 3 m/min every 3 min until exhaustion (i.e. maximum speed), which was defined as the time that rats touched the end of the treadmill five times in 1 min( Reference Ferreira, Rolim and Bartholomeu 23 ). The ILT was performed three times with an interval of 48 h between them. From the animals’ physical performance in these tests, we randomly selected twelve rats to compose the Exe groups.

After this selection, rats were submitted to a 6-week treatment, which included supplementation with fermented milk or potable water (control), administered orally. On the 5th week of treatment, the Exe groups were again submitted to adaptation on the treadmill for 1 week. Then, the rats performed the ILT two times, with 48 h of resting between the tests. The ILT was conducted to establish performance data, such as maximum speed, time and distance. As no discrepancy was found between tests, we adopted the average values. After this period, the rats from the Exe groups were submitted to an acute aerobic exercise session with a continuous intensity corresponding to 85 % of the maximum speed obtained in the ILT.

A period of 12 h after acute exercise, the animals were euthanised. The no-exercise groups were placed on the treadmill (turned off) for 15 min to mimic the stress caused by the ambience of a different cage. These animals were also euthanised after 12 h. Our previous experience (undisclosed data) is that after 12 h of the exhaustive exercise session there may be increased inflammatory process and changes in the gut structure in rats. For this reason, we chose to perform euthanasia after 12 h of the exhaustive exercise session.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR (quantitative PCR)

Extracted RNA (1 µg) was used for reverse transcription containing OligodT (500 µg/ml), 10 nm dNTP Mix, 5× First Strand Buffer, 0·1 m dithiothreitol and 200 U RT (MMLV Reverse Transcriptase; Promega®). Reverse transcription was conducted at 70°C for 10 min. The cycle continued at 42°C for 60 min after the addition of the enzyme. The enzyme was deactivated at 95°C for 10 min.

Gene expression levels were assessed by fluorescence quantification with a QuantStudio Real-Time System (Thermo Fisher Scientific®). The reaction consisted of complementary DNA diluted in a mix containing Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems®), Milli-Q water and respective sense and antisense initiators. The cycling conditions were 60°C for 1 min, 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, and amplification occurred in forty cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s with an annealing/extension step at 60°C for the 60 s. Analyses were performed using the

![]() $$2^{{{\minus}\Delta \Delta C_{t} }} $$

method, where ΔΔC

t

=(C

t

sample−C

t

internal control from the same sample)−(C

t

control−C

t

internal control from the same control sample). This formula is based on the supposition that the rate of C

t

change v. the rate of target copy change is identical for the gene of interest and the β-actin internal control.

$$2^{{{\minus}\Delta \Delta C_{t} }} $$

method, where ΔΔC

t

=(C

t

sample−C

t

internal control from the same sample)−(C

t

control−C

t

internal control from the same control sample). This formula is based on the supposition that the rate of C

t

change v. the rate of target copy change is identical for the gene of interest and the β-actin internal control.

All primer pairs were synthesised by Sigma Life Science, as follows: ACTB, 5'-GTCTCACCACTGGCATTGTG-3' and 5'-TCTCAGCTGTGGTGGT-3'; CLDN1, 5'-CTGGGAGGTGCCCTACTTT-3' and 5'-CCGCTGTCACACGTAGTCTT-3'; ZO-1, 5'-GAGGCTTCAGAACGAGGCTATTT-3' and 5'-CATGTCGGAGAGTAGAGGTTCGA-3'; IL1B, 5'-CACCTCTCAAGCAGAGCACAG-3' and 5'-GGGTTCCATGGTGAAGTCAAC-3'; IL6, 5'-TCCTACCCCAACTTCCAATGCTC-3' and 5'-TTGGATGGTCTTGGTCCTTAGCC-3'; and TNF, 5'-AAATGGGCTCCCTCTCATCAGTTC-3' and 5'-TCTGCTTGGTGGTTTGCTACGAC-3'.

Histology

The intestinal structure of animals was analysed by histology. The distal colon was frozen in isopentane, cooled in liquid N2 and stored at -80°C, and then cut into portions of 10 µm (thickness) using a cryostat (model CM1860; Leica®). To reveal the general morphology, the non-fixed histological cuts were dyed in a solution of haematoxylin and eosin (1 % w/h for each). The images were obtained under a microscope (Leica®) using the LAS X software.

From the obtained images, we assessed the distance between intestinal villi using ImageJ software. All four images were analysed for each rat, with three per experimentation group.

Immunofluorescence

Transversal sections from the distal colon for immunostaining were fixed in cooled acetone (−20°C) with 0·2 m phosphate buffer for 10 min, washed with saline PBS three times for 3 min each and then blocked with 0·1 glycine/0·2 % TritonX-100 in PBS buffer for 1 h. Posteriorly, slides were incubated in a solution containing a primary antibody, 3 % normal goat serum and 0·3 % Triton X-100/0·1 m (three times for 10 min each), assembled with Vectashield mounting medium for immunofluorescence with 40,6-diamididino-2-phenylindole (catalogue no. H-1200; Vector Labs®) and coverslips. The primary antibodies used for immunolocalisation were claudin-1 (code: 374900; Life Technologies do Brasil®) and ZO-1/TJP1 (code: 402200; Life Technologies do Brasil®). The secondary antibodies were donkey Cy3 anti-mouse (1:500; catalogue no. 715–165–150; Jackson Lab®) and donkey Cy3 anti-rabbit (1:500; catalogue no. 711–165–152; Jackson Lab®). The images were obtained using a microscope and LAS X software.

Myeloperoxidase activity

The migration of neutrophils to rats intestines was evaluated through kinect-colourimetric assay of myeloperoxidase (MPO). Approximately 0·3 g of distal colon was weighed and samples were homogenised in buffer (0·1 m NaCl, 0·02 m NaPO4, 1·015 m Na EDTA, pH 4·7) and centrifuged at 1509 g for 15 min. The sediment was submitted to hypotonic lysis (1·5 ml of NaCl solution at 0·2 %, followed by the addition of an equal volume of NaCl solution at 1·6 % and glucose 5 %). After centrifugation, the sediment was resuspended in 0·05 M NaPO4 buffer (pH 5·4) containing 0·5 % hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. After this step, the sediment was instantly frozen in liquid N2 three times, centrifuged at 11 963 g for 15 min and then again homogenised. The MPO activity in resuspended sediment was analysed by measuring alterations in optical density at 450 nm, using tetramethylbenzidine (1·6 nm) and H2O2 (0·5 mm). Results were calculated by comparing the optical density of the supernatant with a standard curve of neutrophil numbers (>95 % of purity).

Microbiota analysis using next-generation sequencing

The intestinal microbiome analysis was performed by Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), by Neoprospecta®. First, the sequencing library preparation was carried out in a two-step PCR protocol using 1 ng of DNA. In the first PCR reaction, the V3–V4 primers, 314F (CCTACGGGRSGCAGCAG) and 806R (GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT), were used at a concentration of 0·2 µm ( Reference Wang and Qian 24 , Reference Caporaso, Lauber and Walters 25 ). This pair of primers has great taxonomy coverage in bacteria and archaea, recognising the highly variable regions V3 and V4 of the bacterial rRNA 16S( Reference Takahashi, Tomita and Nishioka 26 ). This first PCR primer contains the Illumina sequences based on TruSeq structure adapter (Illumina®), allowing the second PCR with indexing sequences. The PCR reactions were always carried out in triplicate using Platinum Taq (Invitrogen®). The final PCR reaction was cleaned up using AMPureXP beads (Beckman Coulter®) and samples were pooled in the sequencing libraries for quantitative PCR quantification using he KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina platforms (KAPA Biosystems®).

The libraries were sequenced using a MiSeq system, using the standard Illumina primers provided in the kit. After sequencing, a bioinformatics pipeline performs sequence demultiplexing, adaptor and primer trimming. To increase the reliability of the read, excluding possible diversity generated by chimeric amplicons or erroneous nucleotide incorporated in PCR, 100 % identical reads were clustered. If any cluster was represented by fewer than five reads, it was not considered in further analysis. Clustered sequences were then subjected to taxonomic classification comparing them with a 16S rRNA database (NeoRefdb; Neoprospecta Microbiome Technologies®). Sequences with at least 99 % identity in the reference database were taxonomically assigned.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated using free sample size calculating software G*Power version 3.1.9.2 (Franz, Universitat Kiel).

The sample was calculated considering the results observed by Chen et al. ( Reference Chen, Wei and Chiu 27 ) and the variable swimming time (ST) in three groups of trained mice: vehicle (ST=4·8); LP10-1× (ST=9·0); and LP10-5× (ST=23·3). Considering these values, we have an effect size of 7·91. With a power of 95 %, 0·05 level of statistical significance and effect size of 7·91, the sample size for each group was calculated to be 2. Considering that the effect of the base study was large, we decided to be conservative and increase the sample number to a total of twenty-four mice randomly assigned into one of the four experimental groups.

Values for initial weight v. final weight and weight curve were expressed as the means and standard deviation and assessed by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test, using repeated measures. For the two independent group comparison, we used the Student’s t test. For microbiota assessment, we elaborate a ratio between order quantification (n Lactobacillale/n Clostridiales) and between genus (n Lactobacillus/n Clostridium). The ratio between the groups and values for Claudin-1, ZO-1, IL1B, IL-6 and TNFa were compared by one-way ANOVA with the Games–Howell post hoc test. The tests were chosen because the group ratios had unequal variances (n reduced by group). In this case, the Games–Howell test avoids error distortions familywise type I and α-type I( Reference Games, Keselman and Rogan 28 ). These statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 and SPSS 15.0.1 software. The significance considered for all tests was P<0·05.

Results

Fermented milk

Before the fermented milk preparation, we evaluated the phenolic content of pomegranate juice extracted directly from the fruit. In addition, we analysed the protein content of the whey protein concentrate. Juice obtained from pomegranate contained 4·64 mmol polyphenols, and from this value we calculated its addition percentage to the fermented milk, aiming to reach 2·625 mmol of polyphenols in the drink used for supplementation. The protein content of whey protein was 77·3 (sd 0·14) %, and we calculated its addition percentage to reach an equivalent dose of 20 g/d for the drink, corrected by animal average weight at each week. Also, we evaluated probiotic viability on the fermented milk, and we observed counts above 8·5 log CFU/ml during all the product shelf life. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics elaborated an Expert Consensus Document in which there is no minimal count of viable probiotic cells to include the claim of a probiotic food( Reference Hill, Guarner and Reid 29 ). Instead, the recommendation is to prove the viability at the appropriate level used in supporting human studies, according to Bertazzoni et al.( Reference Bertazzoni, Donelli and Midtvedt 30 ) and according to the legislation for probiotics in Brazil( 31 ). However, some countries suggest 9 log CFU per serving, such as Italy and Canada( Reference Hill, Guarner and Reid 29 ). The proposed serving of the fermented milk intended for human consumption is 140 ml, which corresponds to 10·6 log CFU of probiotic cells. Comparing this quantity of probiotic cells given to a 70-kg human, it is equivalent to the quantity of probiotics given to the rats (approximately 500 g) in this research. The supplementation with fermented milk did not result in adverse events in the rats.

Animals’ physical performance

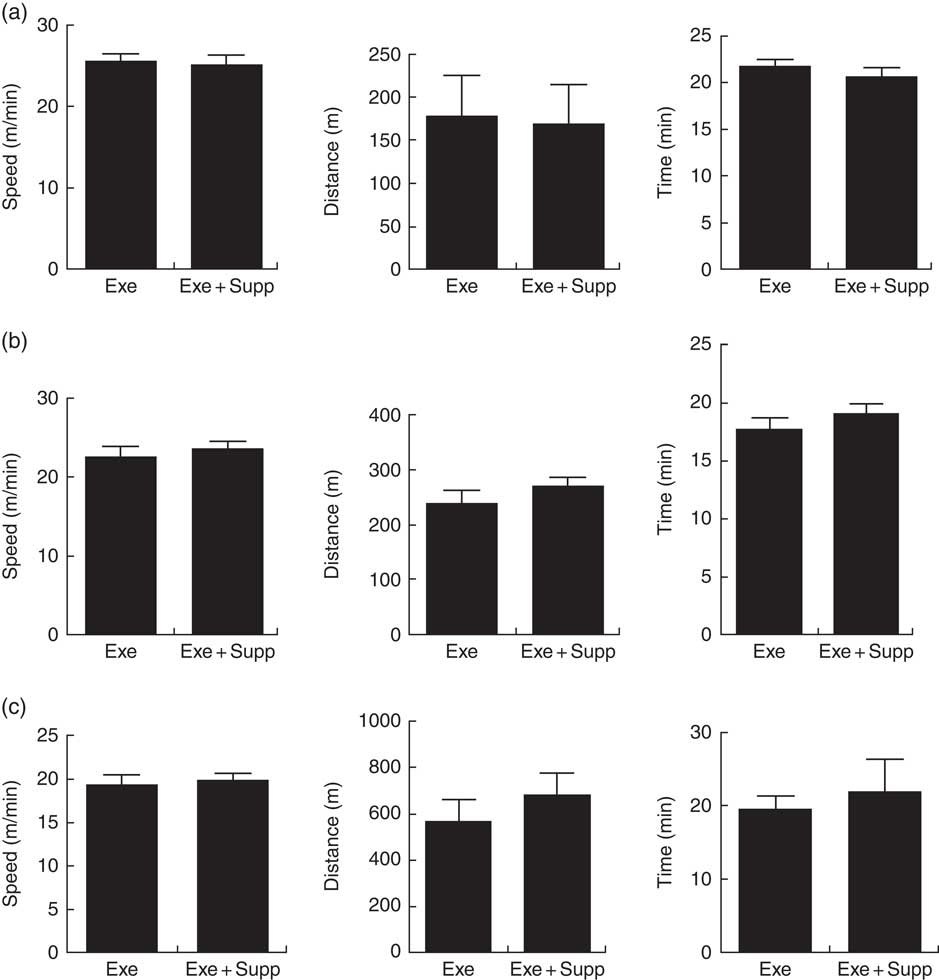

Fig. 1(a) shows results of the progressive test until exhaustion before treatment, showing that Exe and Exe+Supp groups presented similar performances. Fig. 1(b) shows results of the same test after treatment, showing no significant difference between groups. Fig. 1(c) presents results of acute exercise at 85 % maximum capacity obtained in the progressive test (Fig. 1(b)) where no improvement in performance was observed after treatment with the fermented milk in comparison with the Exe-only group.

Fig. 1 Animals’ performance on treadmill running. (a) Progressive test until exhaustion (maximum test) before treatment (speed in m/min, distance in m, time in min). (b) Progressive test until exhaustion post treatment (speed in m/min, distance in m, time in min). (c) Acute exercise at 85 % of the maximum test (speed in m/min, distance in m, time in min). Six animals from each group were submitted to these tests. Values are averages and standard deviations. No statistical difference was observed between groups. Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented.

Body evaluation and intestinal content

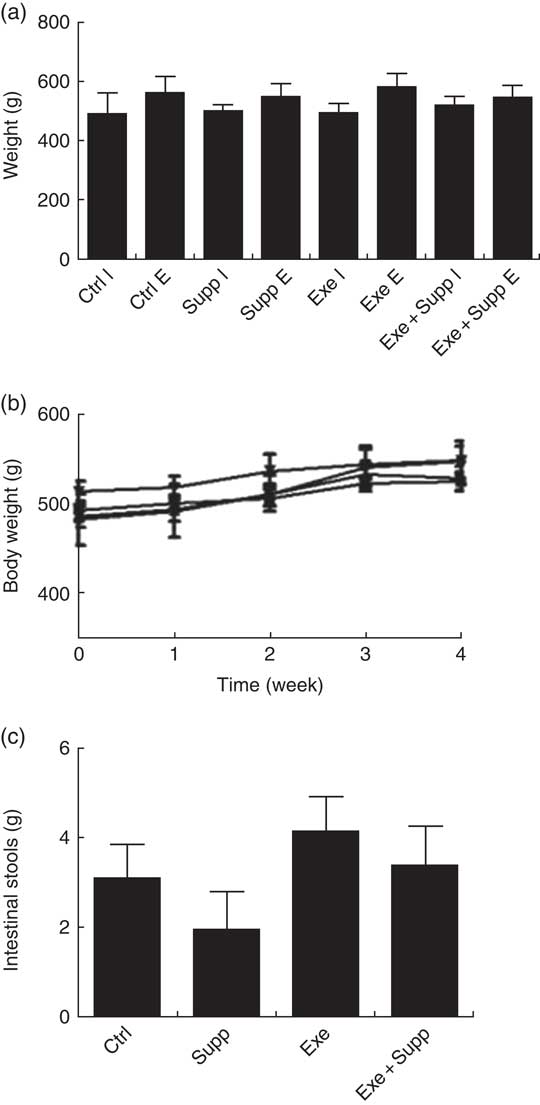

The supplementation with fermented milk does not lead to weight gain in comparison with control rats (Fig. 2(a) and (b)). We highlighted that only supplemented animals presented less faecal gut content in comparison with the other groups, with no statistical difference (Fig. 2(c)).

Fig. 2 Body evaluation. (a) Initial weight v. final weight. (b) Body weight curve. (c) Faeces weight collected in the colon. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Values are averages and standard deviations. No statistical difference was observed between groups. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented; B: ![]() , Ctrl;

, Ctrl; ![]() , Supp;

, Supp; ![]() , Exe;

, Exe; ![]() , Exe+Supp.

, Exe+Supp.

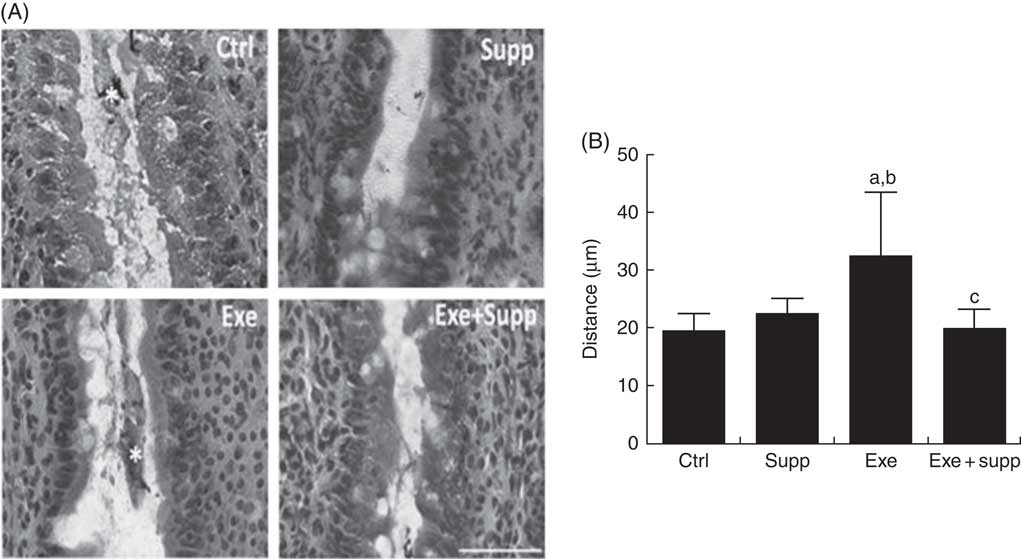

Histology and intestinal villi distance

Fig. 3(A) presents distal colon histology, showing that the Supp group presented similar intestinal villi in comparison with the Ctrl group, whereas the Exe group presented larger villi interspace. The Supp+Exe group demonstrated preservation of the original interspace. Evaluating the distance between intestinal villi using ImageJ (Fig. 3(B)), we found that the Exe group presented significantly more space compared with the Ctrl and Supp group, indicating that high-intensity acute exercise can cause structural changes in this mucosa (one-way ANOVA: P=0·001, a=P=0·025 v. Ctrl, b=P=0·098 v. Supp). On the other hand, the beverage preserved the original distance between villi, indicating the protector effect of supplementation on high-intensity acute exercise situations (c=P<0·030 v. Exe).

Fig. 3 Histology and intestinal villi distance. (A) Histology from the intestinal colon, bar=50 µm. (B) Villi distance in the intestinal colon. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. One-way ANOVA: P<0·001. Values are averages and standard deviations. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented. Post hoc Games–Howell, where a=P<0·025 v. Ctrl, b=P<0·098 v. Supp and c=P<0·030 v. Exe.

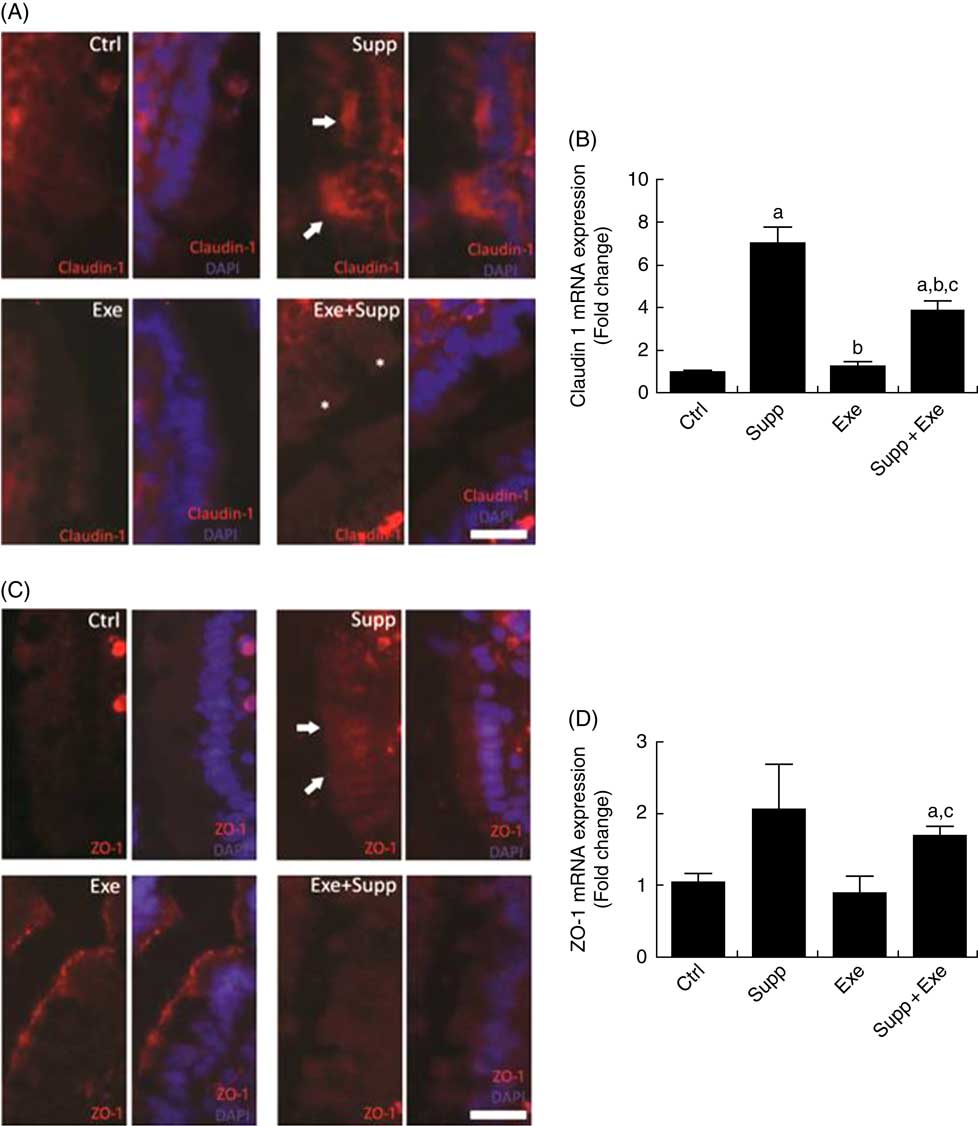

Immunofluorescence and barrier function protein expression

Claudin-1 protein labelling is shown in Fig. 4(A), in which it is possible to note that the Supp group showed accumulation of claudin-1 at specific regions (arrows, Fig. 4(A)) and Exe+Supp group presented similar labelling to Ctrl group, whereas the Exe group exhibited a strong labelling reduction. On analysing claudin-1 mRNA expression (Fig. 4(B)), we found that supplementation with the fermented milk significantly increased claudin-1 expression (one-way ANOVA: P<0·001, a=P=0·004 v. Ctrl). Intense acute exercise did not change the protein expression in comparison with the Ctrl group. However, the Exe+Supp group presented an increase in claudin-1 expression (a=P=0·004 v. Ctrl, b=P=0·004 v. Supp, a=P=0·005 v. Ctrl, b=P=0·042 v. Supp and c=P=0·004 v. Exe), showing the influence of supplementation on this protein expression. The ZO-1 labelling pattern was found to be similar to claudin-1, where the Supp group presented increased expression and accumulation in specific epithelial regions (arrows, Fig. 4(C)). The ZO-1 mRNA levels showed similar modulation to claudin-1 (one-way ANOVA: P=0·008, a=P=0·017 v. Ctrl and c=P=0·050 v. Exe), as shown in Fig. 4(D).

Fig. 4 Immunofluorescence and barrier function protein expression. (A) Claudin-1 immunofluorescence, bar=50 µm. (B) Claudin-1 expression. One-way ANOVA: P<0·000. Values are averages and standard deviations. Post hoc Games–Howell, where a=P<0·004 v. Ctrl, b=P<0·004 v. Supp, a=P<0·005 v. Ctrl, b=P<0·042 v. Supp, c=P<0·004 v. Exe. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. (C) Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) immunofluorescence, bar=50 µm. (D) ZO-1 expression. One-way ANOVA: P<0·088. Values are averages and standard deviations. Post hoc Games–Howell, where a=P<0·017 v. Ctrl and c=P<0·050 v. Exe. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented.

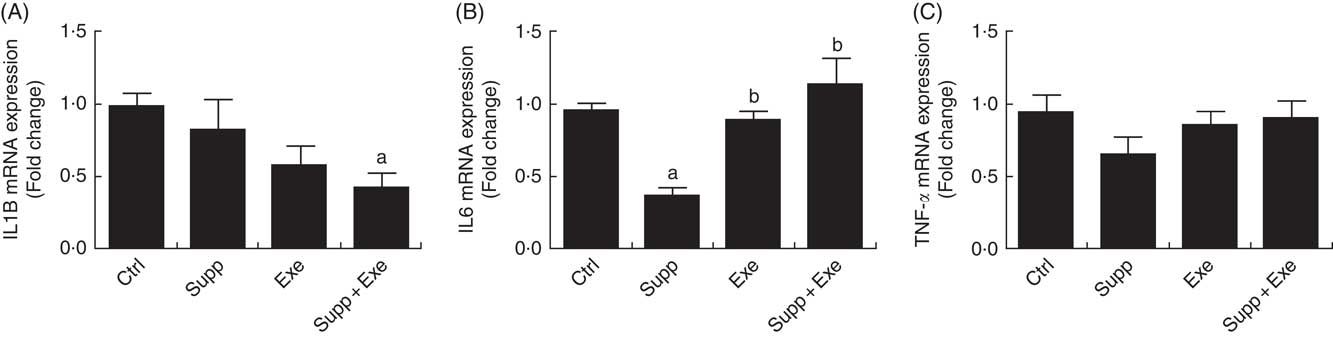

Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression

Cytokine IL-1β expression (Fig. 5(A)) was lower in the group with exercise and fermented milk supplementation (Supp+Exe) (one-way ANOVA: P<0·05, a=P<0·018 v. Ctrl). In the analysis of IL-6 expression (Fig. 5(B)), it was observed that the level of the cytokine in the group with supplementation (Supp) was lower in relation to the control group (Ctrl). The group of exercised rats (Exe) and the group supplemented and submitted to the exercise protocol (Supp+Exe) presented an increased IL-6 compared with the control group. Regarding the analysis of TNFα expression, there was no change in the groups studied.

Fig. 5 Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. (A) IL1B expression. One-way ANOVA: P<0·051. Values are averages and standard deviations. Post hoc Games–Howell, where a=P<0·018 v. Ctrl. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. (B) IL-6 expression. One-way ANOVA: P<0·000. Values are averages and standard deviations. Post hoc Games–Howell, where a=P<0·000 v. Ctrl, b=P<0·001 v. Supp and b=P<0·008 v. Supp. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. (C) TNFα expression. One-way ANOVA: P<0·325. Values are averages and standard deviations. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented.

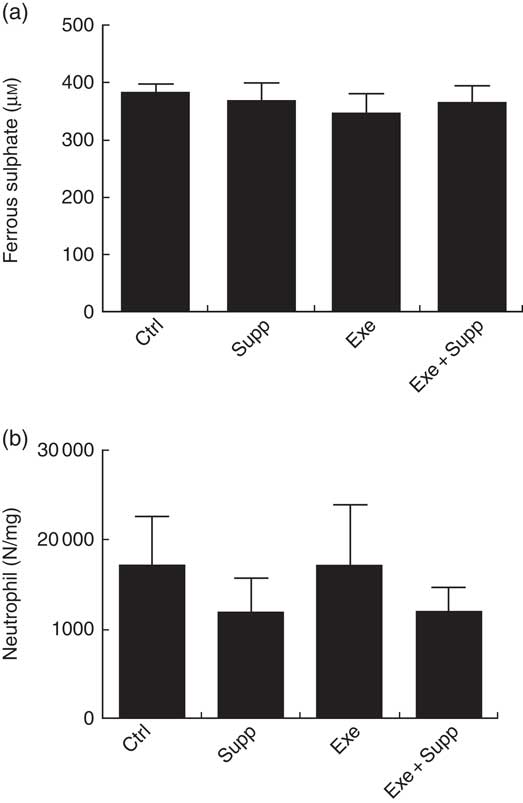

Antioxidant analyses on blood (serum) and myeloperoxidase activity

Fig. 6(a) demonstrates antioxidant analyses on blood serum using the FRAP method. No significant differences were found between groups. Regarding MPO activity in the distal colon (Fig. 6(b)), an analysis that helps to determine local inflammation, we observed that supplementation seems to decrease neutrophil infiltration, but no statistical difference was observed between groups.

Fig. 6 Antioxidant analysis on blood serum and myeloperoxidase activity. (a) Antioxidant analysis on blood serum by ferric-reducing antioxidant power. (b) Myeloperoxidase activity analysis. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Values are averages and standard deviations. No statistical difference was observed between groups.

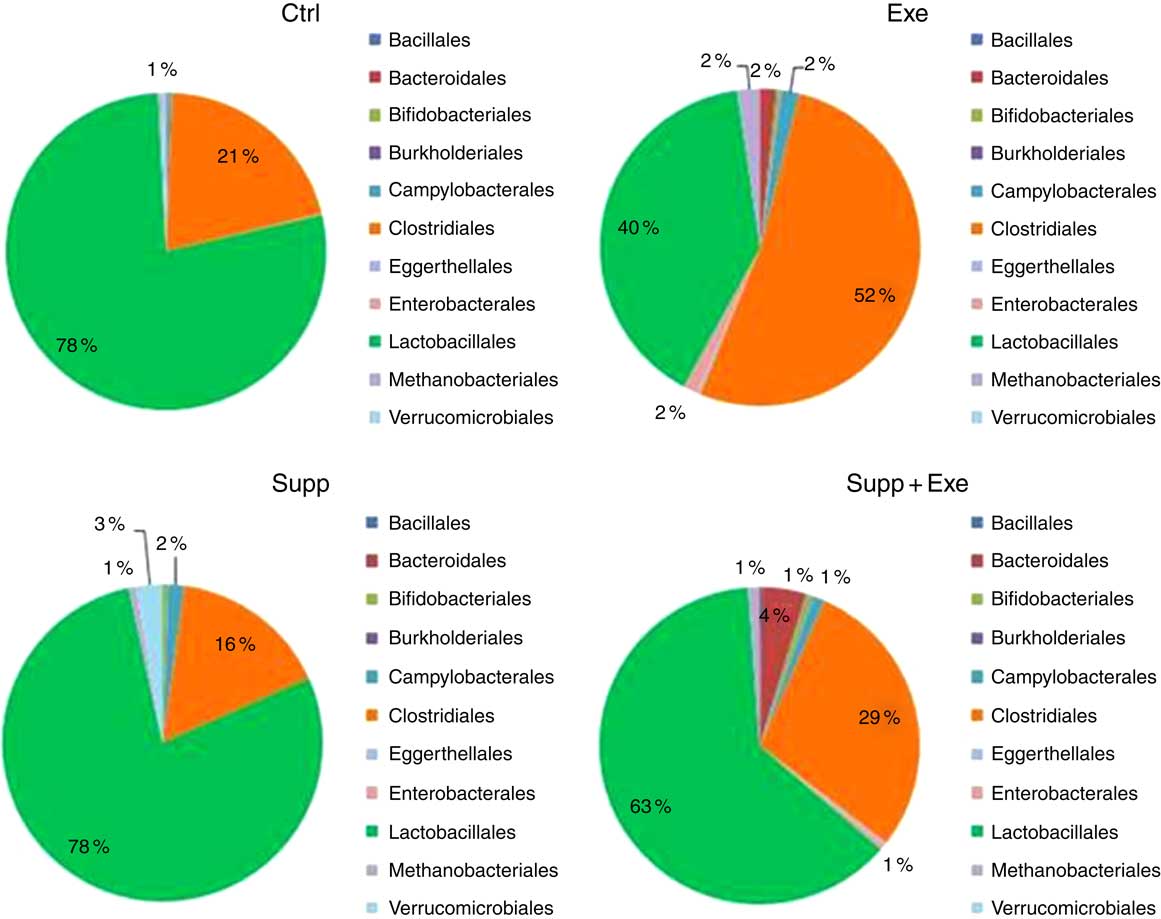

Microbiota analyses by order, genus and species

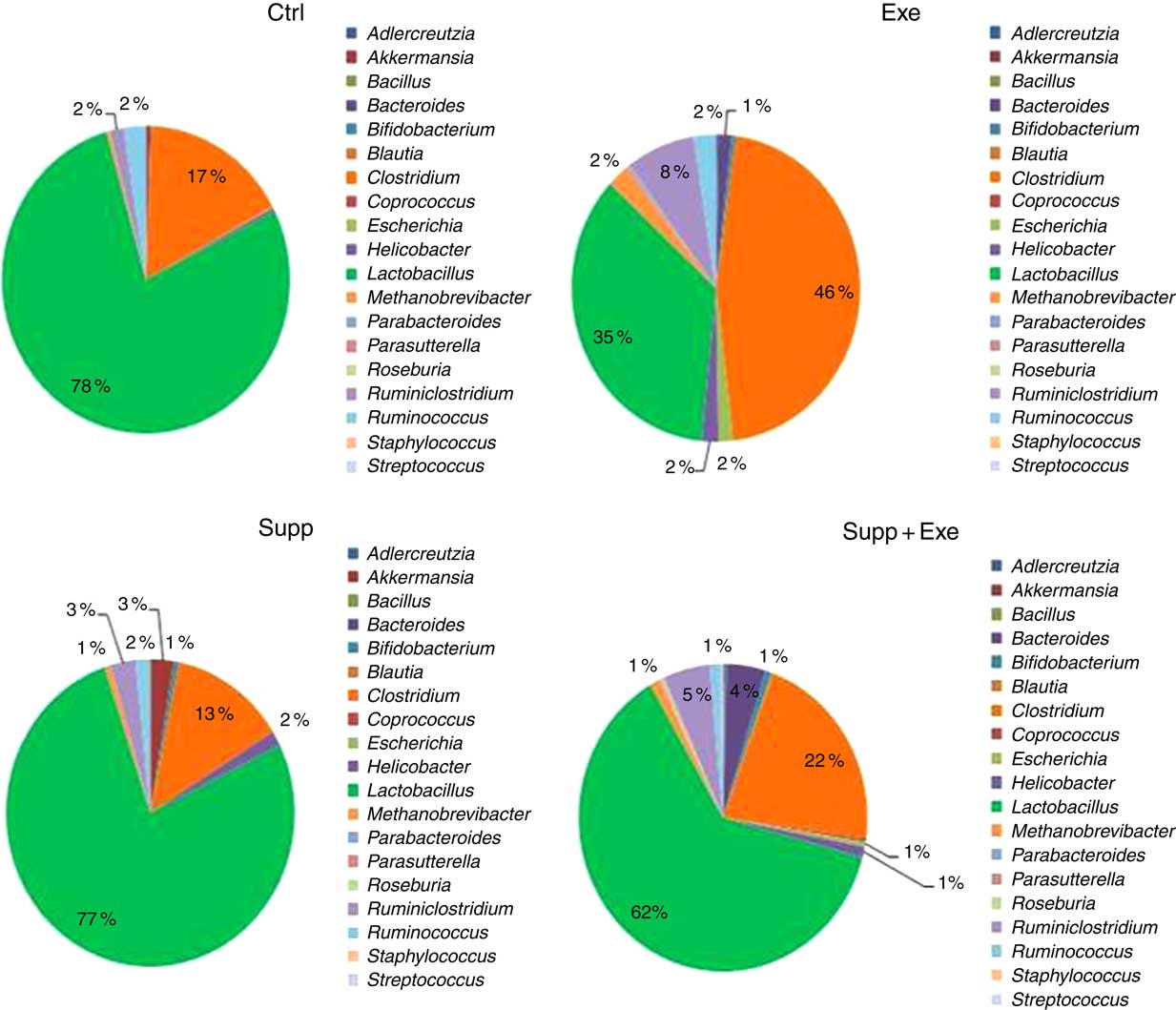

In Figs 7–11, we present NGS results of Wistar rats’ microbiota. We observed that the order Lactobacillale represented one of the major components of these animals’ microbiota, totalising average values of 78 % of total population on control animals (Fig. 7). On comparing Ctrl animals and Supp (not exercised) first, we observed that supplementation with the fermented milk modulated proportions of orders found in the microbiota, increasing the order Bifidobacteriales without decreasing the proportion of Lactobacillale. However, the order Clostridiales was reduced from 21 % to 16 % approximately.

Fig. 7 Microbiota analysis by order. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Values are averages and standard deviations. No statistical difference was observed between groups. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented.

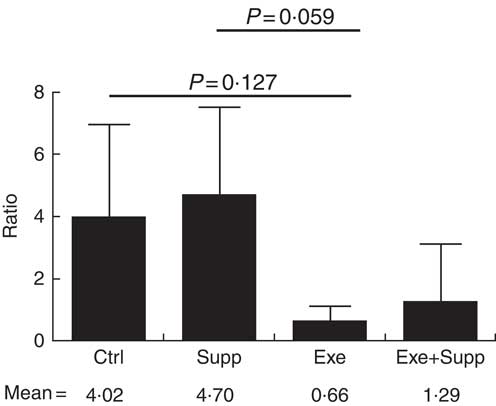

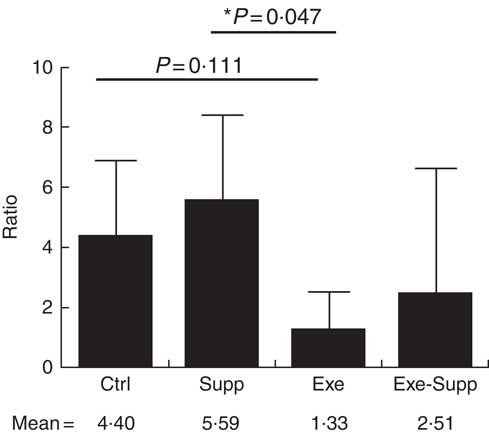

Fig. 8 Ratio of Lactobacillae:Clostridiales orders. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Values are averages and standard deviations. ANOVA test with Games–Howell post-test. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented.

Fig. 9 Microbiota analysis by genus. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Values are averages and standard deviations. No statistical difference was observed between groups. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented.

Fig. 10 Ratio of Lactobacillus:Clostridium genera. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Values are averages and standard deviations. ANOVA test with Games–Howell post-test. *P<0·05. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented.

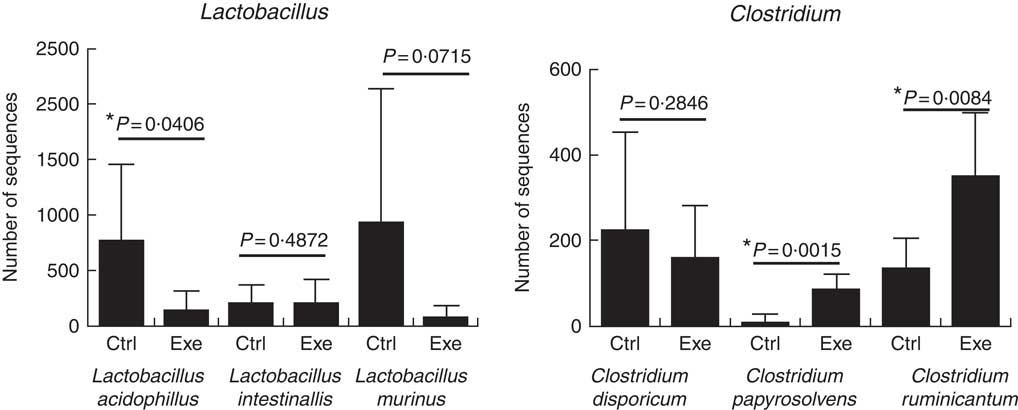

Fig. 11 Exercise decreases Lactobacillus ssp. population and increases Clostridium ssp. population. Six animals from each group were used for this evaluation. Values are averages and standard deviations. Unpaired t. *P<0·05. Ctrl, control; Exe, exercised; Exe+Supp, exercised and supplemented.

B. animalis did not initially compose rats’ microbiota, with B. pseudolongum being the only autochthonous belonging to the order Bifidobacteriales, but in reduced proportion (data not shown). The supplementation with the fermented milk introduced B. animalis species in the Exe+Supp and Supp group (data not shown). Intense acute exercise caused a considerable change in the percentage of relative abundance of microbial order on animals’ microbiota. Establishing the ratio of Lactobacillale/Clostridiales, we observed that animals from the Ctrl and Supp groups presented values between 4·02 and 4·70 of these two orders; that is, the proportion was four times higher for the Lactobacillale group compared with the Ctrl group and almost five times superior to the supplemented group. This condition was changed by intense exercise, denoting supremacy of Clostridiales (Fig. 8). Supplementation of exercised animals with the fermented milk tended to improve this proportion, elevating Lactobacillale. Nevertheless, there was no statistical difference between groups for the two microbial orders cited.

Taken together, our results obtained for the genus were similar to those obtained for order classification, with reduction of Lactobacillus proportion and increase of Clostridium owing to exercise (Fig. 9). When the Lactobacillus:Clostridium ratio was observed, the same tendency was confirmed, with a statistical difference between the Supp and Exe groups (Fig. 10). To our best knowledge, this result was not previously reported in the literature.

A total of twenty-nine microbial species were identified to comprise Wistar rats’ microbiota in this study. To prove the suppressor effect of intense acute exercise on the Lactobacillus genus, we statistically compared the number of sequences of three species found on rats’ microbiota, as presented in Fig. 11. We observed a statistically significant reduction of Lactobacillus acidophilus and the tendency of reduction of Lactobacillus murinus (P=0·07). The same figure shows the opposite effect for Clostridium papyrosolvens and Clostridium ruminicantum, which presented a significant increase between animals that suffered stress caused by exercise.

Discussion

Our results showed that supplementation with fermented milk did not alter the parameters of performance in Wistar rats. The most suitable model for studying sports performance with respect to running is the mouse model. In this study, Wistar rats were used owing to the need for a greater gastric volume to enable daily administration of 2 ml of the beverage in order to reach stipulated amounts of the bioactives compounds. Lollo et al.( Reference Lollo, Cruz and Morato 32 ) showed that supplementation of Wistar rats with cheese containing probiotics and submitting them to intense acute exercise prevented immunosuppression caused by strenuous exercise but did not change performance directly. Other research with intense exercise practitioners and endurance athletes showed that supplementation with probiotics also did not alter the physical performance( Reference Cox, Pyne and Saunders 33 – Reference Valimaki, Vuorimaa and Ahotupa 37 ). A study with humans demonstrated ergogenic effect of supplementation with probiotics, showing a significant increase in race time( Reference Shing, Peake and Lim 38 ). In mice, Lactobacillus plantarum TWK10 supplementation improved exercise performance according to Chen et al. ( Reference Chen, Wei and Chiu 27 ).

Studies of supplementation with pomegranate extract or pomegranate juice in humans submitted to high-intensity aerobic exercise showed a decrease of oxidative stress caused by exercise but did not show improvement in physical performance( Reference Fuster-Munoz, Roche and Funes 15 , Reference Crum, Che Muhamed and Barnes 39 ).

Animals supplemented with fermented milk presented lower faecal content in the colon, compared with the other groups. Supporting our results, previous studies have shown that consumption of probiotics decreases intestinal transit time by increasing volume and weight of faeces, gas production, reduction in intestinal pH, increase of SCFA concentration, bacterial metabolism of bile acids and cholecystokinin production( Reference Rolfe 40 ). In addition, other research also showed that physical exercise could decrease intestinal transit time positively or negatively, as observed in cases of intense exercise where a reduction in intestinal blood flow occurs, causing gastrointestinal discomfort( Reference Gil, Tomas-Barberan and Hess-Pierce 41 – Reference van Nieuwenhoven, Brouns and Brummer 43 ). Still, in our study, the Exe group without supplementation presented very similar results when compared with the Ctrl group. Van Nieuwenhoven et al.( Reference van Nieuwenhoven, Brouns and Brummer 43 ) assessed runners and professional bikers regarding intestinal habits, also showing delay in intestinal transit owing to intense exercise.

The intestine is an organ that, beyond digestion and absorption functions, acts as a protective barrier against pathogenic agents( Reference Lu, Ding and Lu 44 ). Assessing intestinal villi through histology, we observed that the consumption of the fermented milk might favour maintenance of the intestinal physiological structure. Meanwhile, intense acute exercise can negatively alter the intestinal integrity. Tight-junction proteins are intercellular junctions that provide a cell–cell adhesion in enterocytes, playing a critical role in permeability regulation of paracellular barrier( Reference Garcia-Hernandez, Quiros and Nusrat 11 , Reference Fanning, Mitic and Anderson 12 , Reference Gunzel and Yu 13 , Reference Lu, Ding and Lu 44 ). In this way, alterations in these proteins lead to the development of pathologies associated with rupture of the intestinal structure and bad nutrient absorption( Reference Lu, Ding and Lu 44 – Reference Li, Zhang and Wang 46 ). Claudins are the most important functional components of tight junctions( Reference Lu, Ding and Lu 44 ). Regulation of claudins occurs on various levels, such as regulation of transcription, post-translational modification, interaction with cytoplasmic scaffolding proteins and interactions with claudins within the same membrane (cis-interaction), as well as with claudins of neighbouring cells (trans-interaction)( Reference Gunzel and Yu 13 ). For claudins to form functional tight-junction strands, they require additional proteins such as the cytoplasmic scaffold proteins ZO-1 and ZO-2, which bind directly to claudins and link them to the actin cytoskeletal network( Reference Overgaard, Daugherty and Mitchell 47 ). Intestinal barrier function can be positively modulated by probiotics, according to a review recently published( Reference Bron, Kleerebezem and Brummer 48 ). However, the molecular mechanisms behind the effects need to be elucidated. Karczewski et al.( Reference Karczewski, Troost and Konings 49 ) administered L. plantarum WCFS1 (1012 cells) in a randomised human cross-over study with seven healthy subjects and made biopsies for gene expression analysis and immunohistochemistry. Administration of L. plantarum significantly increased the staining of ZO-1 in the apical part of the cell near the vicinity of the tight junctions, but not the peak fluorescence intensity or cytoplasmic distribution of ZO-1. The mechanism was shown to be dependent on Toll-like receptor 2 signalling. Intense physical exercise can negatively alter intestinal barrier function, as demonstrated by van Wijck et al.( Reference van Wijck, Lenaerts and van Loon 9 ), whereas consumption of probiotics can favour and re-establish this barrier. Our work demonstrated that supplementation with fermented milk increased tight-junction protein expression. Therefore, probiotics can alter tight-junction protein expression and improve in vitro and animal model barrier function( Reference Macpherson and Harris 50 , Reference Keita and Soderholm 51 ). Patel et al.( Reference Patel, Myers and Kurundkar 52 ) administered antibiotics to neonate mice, demonstrating a decrease in barrier function and claudin expression. After administration of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, they presented accelerated intestinal barrier maturation and induction of claudin expression. This shows that probiotics administration can accelerate the expression of proteins involved in intestinal barrier function in immature intestine( Reference Patel, Myers and Kurundkar 52 ). Moreover, Lu et al.( Reference Lu, Ding and Lu 44 ) have demonstrated that glutamine deprivation decreases claudin-1 expression. The fermented milk administered in this study contains whey protein, specially composed of glutamine, offering a series of benefits, such as strengthening the intestine and immune system and allowing health protection during physical exercise( Reference Cruzat, Krause and Newsholme 1 , Reference Castell and Newsholme 53 , Reference Li and Neu 54 ).

Cytokines are modulated by the physiological stimulus, such as hormones, nutrients, oxidative stress and physical exercise, and these alterations depend on intensity, duration and type of exercise( Reference Cruzat, Krause and Newsholme 1 , Reference Cannon 55 – Reference Drenth, Van Uum and Van Deuren 57 ). Otherwise, on strenuous and intense exercise, circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 are increased above normal levels. A previous study showed a 100-fold increase in plasmatic concentrations of IL-6 and 1-fold to 2-fold increase in the concentration of IL-1β and TNF-α after long and intense exercise( Reference Ostrowski, Rohde and Asp 58 ). In the present study, there was no change in IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα with exercise. Only the rats in the exercise group and those that also received supplementation had reduction in IL-1β cytokine expression.

Cruzat et al.( Reference Cruzat, Rogero and Tirapegui 59 ) found that supplementation of l-glutamine can attenuate muscle lesion and inflammation, as well as reduce the levels of TNF-α induced by strenuous exercise.

Moreover, our results showed no differences in antioxidant activity on animals’ blood serum. However, on assessing MPO activity in the distal colon, we found that supplementation with the functional beverage promotes reduction in neutrophil infiltration, although not statistically significant. A study demonstrated that L-glutamine availability increases neutrophil and lymphocyte activity and function( Reference Pithon-Curi, Trezena and Tavares-Lima 60 ). In addition, there is a relationship between neutrophil infiltration, muscle damage and reactive oxygen species generation in the inflammatory process( Reference Niess and Simon 61 ). Continuous moderate exercise reduces reactive oxygen species through endogenous antioxidant system adaptation( Reference Cruzat, Krause and Newsholme 1 , Reference Fuster-Munoz, Roche and Funes 15 ). Exacerbated inflammation and oxidative stress can cause a decrease in muscle function( Reference Fuster-Munoz, Roche and Funes 15 ). The endogenous antioxidant system can protect the body against oxidative damage caused by physical exercise. However, they may not be sufficient for elite athletes or in intense exercise( Reference Cruzat, Krause and Newsholme 1 ). Therefore, many strategies have been used to avoid or minimise these damages, such as nutritional interventions with antioxidants( Reference Fuster-Munoz, Roche and Funes 15 , Reference Sharma, McClees and Afaq 18 , Reference Crum, Che Muhamed and Barnes 39 ). In this context, pomegranate juice is rich in polyphenols such as flavonols, anthocyanins and ellagitannins( Reference Fuster-Munoz, Roche and Funes 15 , Reference Gil, Tomas-Barberan and Hess-Pierce 41 ), and can be used as an exogenous antioxidant.

Intestine and microbiota are important organs for physical performance, as they are responsible for delivery of nutrients, water and hormones during exercise( Reference Clark and Mach 7 ). Intestinal microbiota can neutralise carcinogens and drugs, protect the host from pathogens, stimulate the immune system and modulate intestinal motility( Reference Clark and Mach 7 , Reference Nicholson, Holmes and Kinross 62 ). In addition, alterations in epithelial functions and microbiota composition can exert influence on obesity-associated inflammation( Reference de La Serre, Ellis and Lee 63 ). The consumption of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium can promote beneficial changes in intestinal activity, such as an increase in barrier function( Reference Mackos, Eubank and Parry 64 ).

Evaluating animals’ microbiota, we observed that the order Lactobacillales was more abundant in Wistar rats from the Ctrl group and that intense acute exercise caused a reduction in this microbial order, that was elevated in these animals and is associated with a well-balanced microbiota (Fig. 7). Animals’ supplementation with fermented milk containing pomegranate juice, whey protein and B. animalis favoured microbiota dynamic balance in exercised animals, supporting maintenance of relative abundance of Lactobacillus species. We highlight that the probiotic used in our beverage does not belong to the Lactobacillus genus, but to the Bifidobacterium genus. Even so, the supplementation created a favourable microenvironment to re-establish proportions of Lactobacillus suppressed by strenuous exercise. A systematic review from Clark & Mach( Reference Clark and Mach 7 ) concluded that supplementation with probiotics can result in the release of beneficial metabolites, improving barrier function, immune functions and metabolic functions in athletes( Reference Clark and Mach 7 ). B. animalis BB12 was chosen after testing other commercial strains (five Lactobacillus species and two Bifidobacterium species) in preliminary tests This strain achieved better viability results in the fermented milk product developed (data not shown). Moreover, BB12 strain has widespread use in food industry( Reference Antunes, Silva and Van Dender 65 ) and there are many health benefits reported in the literature( Reference Shah 66 ).

We carefully evaluated the effect of the supplementation on Akkermansia muciniphila proportion, as it has been considered a therapeutic micro-organism with an important role in the mutualism between intestinal microbiota and host, interfering with barrier function and homoeostasis( Reference Everard, Belzer and Geurts 67 ). Nevertheless, we did not observe the major proportion of this species related to the supplementation with fermented milk (data not shown), nor did we observe an increase in this genus owing to exercise, as observed by Clarke et al.( Reference Clarke, Murphy and O’Sullivan 68 ) and Barton et al.( Reference Barton, Penney and Cronin 69 ).

Although there are a few studies on this thematic area so far, some publications point microbiota modulation as one of the many effects of physical exercises. In the study by Mika et al.( Reference Mika, Van Treuren and Gonzalez 70 ), young rats submitted to treadmill running presented changes in phylum proportions, with an increase in Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes, a pattern associated with a lean phenotype by some researchers( Reference Ley, Turnbaugh and Klein 71 , Reference Turnbaugh, Hamady and Yatsunenko 72 ). On the genus taxonomic level, they observed changes in the proportion of six genera on young and adult rats submitted to running, specifically: Rikenellaceae g_, Blautia spp., Turicibacter spp., Anaerostipes spp., Methanosphaera spp., Desulfovibrio spp.( Reference Mika, Van Treuren and Gonzalez 70 ). Our results did not support these findings.

Our research pointed to a statistically significant rise of C. papyrosolvens and C. ruminicantum due to strenuous exercise, as presented in Fig. 11. These findings support results from the study by Batacan et al.( Reference Batacan, Fenning and Dalbo 73 ) on rodents, who observed some species of Clostridium being induced by HIIT exercise (high-intensity interval training), such as Clostridium geopurificans and Clostridium saccharolyticum. It is important to emphasise that the Clostridium genus is associated with dysbiosis, inflammatory bowel diseases and colon cancer( Reference de La Serre, Ellis and Lee 63 , Reference Hsu, Liao and Chung 74 ). Interestingly, a study showed that a toxin produced by Clostridium difficile could alter barrier function, modifying tight-junction proteins such as Occludin, ZO-1 and ZO-2( Reference Nusrat, von Eichel-Streiber and Turner 75 ).

Another important finding in our study was that strenuous exercise caused a decrease in relative abundance of the Lactobacillus genus (Fig. 9), which was statistically significant for L. acidophilus when compared with control animals (Fig. 11). L. acidophilus is a recognised health promoter species, being widely used by the food and pharmaceutical industry as a probiotic. The supplementation with the fermented milk tended to benefit Lactobacillus proportions and reduced Clostridium proportions (Fig. 9). Sanders suggests that bifidobacteria can modulate colon bacteria activity associated with diseases in animals( Reference Sanders 76 ); that is, as bifidobacteria population increases, a reduction is observed for species belonging to the Clostridium genus( Reference de La Serre, Ellis and Lee 63 , Reference Hsu, Liao and Chung 74 ).

Literature shows outcomes in different directions regarding Lactobacillus. Choi et al.( Reference Choi, Eum and Rampersaud 77 ) studied exercised mice, which presented a higher abundance of the order Lactobacillales compared with sedentary animals. Similar results were obtained by Queipo-Ortuno et al.( Reference Queipo-Ortuno, Seoane and Murri 78 ), who showed an increase in Lactobacillus proportion owing to exercise, adopting a rat model and treadmill running. Batacan et al.( Reference Batacan, Fenning and Dalbo 73 ) observed an increase of Lactobacillus johnsonii in rodents submitted to light-intensity training running protocol. We suggest that differences in protocols (mainly intensity) are a determining factor to explain the divergence between these findings and the results of our study. In general lines, intense physical exercise seems to compromise intestinal barrier function, decrease intestinal motility and decrease the relative abundance of Lactobacillus species as increase proportion of Clostridium species. L. acidophilus was reduced, and C. papyrosolvens and C. ruminicantum increased by strenuous exercise, with statistically significant differences. It is important to emphasise that the Clostridium genus includes several human pathogens, including Clostridium botulinum (causative agent of botulism) and C. difficile, the most significant bacterial cause of diarrhoea in adults. At present, we observed that strenuous exercise caused microbiota dysbiosis with an increase in the relative proportion of Clostridium ssp., which may represent health risks. Overgrowth of potentially pathogenic micro-organisms can result in tight-junction disruption( Reference Hell, Bernhofer and Stalzer 79 ). On the other hand, we observed that the supplementation of the rats with the probiotic fermented milk provided an increase in the structural protein expression of tight junctions, which may result in the strengthening of the barrier function against pathogens. In this way, supplementation proved to be an attractive option in strenuous exercise.

In this study, no statistical difference was obtained in some parameters. The possible factors involved were the variability of the responses associated with the restricted number of animals per group. However, the number of animals used followed the requirements of the Committee on Ethics in Animal Experimentation (CEUA), in accordance with international guidelines.

According to the review published by Clark & Nuria( Reference Clark and Mach 7 ), nowadays, a consensus of probiotic recommendation to supplementation in athletes does not exist. Nevertheless, new studies might point to specific strains or dosages to modulate various adverse events caused by strenuous exercise practice, such as a break of homoeostasis, dysbiosis, endotoxaemia and so on, which might be associated with gastrointestinal discomfort, immunosuppression and even mood changes.

The fermented milk developed in this study was supplemented with probiotics, was rich in protein and polyphenols from pomegranate juice and was capable of benefiting acute exercised animals. Although this beverage was assessed through this prism, its use also can be prospected to humans in acute exercise and in other extreme situations of hypermetabolic states as occurs in malnutrition.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the students Luiz Guilherme Salvino da Silva, Vitor Rosetto Muñoz, Rafael Calais Gaspar, Bruna de Melo Aquino, Gabriella Rocha and Franciele Carneiro da Silva for their assistance.

The authors thank Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) for research financing (project no. 15/07299-7) and scholarship concession (no. 15/13972-6). The authors also thank Danisco and Chr-Hansen for kindly providing the probiotic cultures used in this study. The founders FAPESP, Danisco and Chr-Hansen had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

F. M. C.: master’s student responsible for all the analyses except for the sequencing of the microbiota. Elaborated the article; I. L. B.: analysis of histology, immunofluorecence and article writing. F. M. S.: molecular biology analyses, interpretation of the results and article writing; P. G. F. Q.: PCRq, RNA extraction and article writing; F. L. P.: analyses of protein quantification, viability of probiotic culture in the fermented milk, phenolic content, animals’ supplementation and the protocol of acute exercise; R. M. N. B.: design of the research project, analysis of phenolic content and antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and blood (serum); J. R. P.: collaborated with acute exercise protocol; D. T. C.: statistical analysis; P. L. C.-F.: collaborated with the design of the project, formulation of the functional beverage and data interpretation; A. E. C. A.: idealisation and coordination of the research project and interpretation of results, especially those related to microbiota analysis.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.