Introduction

Between 1937 and 1942 oil nationalizations in Bolivia and Mexico established a period of tension and conflict with US companies and government. While in both cases the foreign companies were finally expelled from the host countries, a closer look at the political processes reveals that Bolivia was less successful than Mexico in maintaining its initial stand in face of the joint pressure of foreign companies and the US government. Why, despite similar contextual conditions, was it more difficult for Bolivian than for Mexican officials to deal with the external pressures to end their respective oil nationalization controversy? The purpose of this study is to explore, in light of the Mexican and Bolivian oil nationalizations of the 1930s, the importance of domestic politics in trying to successfully maintain divergent preferences against more powerful international actors.

Our work is part of a wider discussion of the dynamics and implications of asymmetry in international relations, often defined in terms of disparities in material capabilities and resources available. Economic, military, demographic, industrial, and technological figures are the most used indicators by students of asymmetric relationships between two or more actors in international politics (Reference MackMack 1975; Reference Keohane and NyeKeohane and Nye 1977; Reference PaulPaul 1994; Reference Arreguín-ToftArreguín-Toft 2001; Reference WomackWomack 2016). But, beyond the recognition of a system in which dissimilar available material resources are certainly relevant, there is still an important discussion about what other factors contribute to explain the results of concrete interactions in asymmetrical dyads. Why is it often observed that the stronger side is not unilaterally able to impose its will over its weaker counterpart? Under which circumstances can the weak side even be the winner in unequal disputes? We join previous academic efforts that take into account the simultaneous relevance of material capabilities and factors of the political context in this type of process, both of which are fundamental for understanding the favorable outcomes for the weaker party in the relationship (Reference SingerSinger 1963; Reference VernonVernon 1971; Reference Keohane and NyeKeohane and Nye 1977; Reference BaldwinBaldwin 1979; Reference WomackWomack 2016).

In this comparative effort, our main contribution relies on a deeper exploration of domestic politics as a space where favorable conditions for the weak can be built. Neoclassical realist foreign policy analysts have already stressed the role of domestic factors as intervening variables in explaining the way a given country interacts with systemic pressures (Reference RoseRose 1998). We propose to explore that role in the context of asymmetry, especially in cases when foreign policy makers on the weaker side are able to build a broad and heterogeneous coalition in the national arena for issues that motivate confrontation with a stronger foreign actor.Footnote 1 We then seek to identify coalition dynamics in the national political arena to assess their weight as a causal condition for the relative success or failure in those situations.

Coalitions, for this purpose, are understood as permanent or temporal alliances between political actors that do not necessarily have the same interests on the same issues and with similar intensity all the time. Following Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960) and Di Tella (Reference Di Tella2003) in their understanding of a political arena in modern polities, we assume that each issue and its implied conflicts have their own potential for a reconfiguration of cleavages and coalitions. We admit the possibility that, depending on the issue and conflict at hand, actors with little affinity among themselves in normal political life may join the same temporal coalition during critical times. Consequently, while looking for actors and coalitions in asymmetrical confrontations, we want to see beyond ruling coalitions and permanent oppositions. This is especially necessary in the analysis of struggles between states and foreign oil companies, which are often assumed by political actors as a critical challenge for the nation as a whole.

The rise and development of national oil industries in Latin America, often at the expenses of foreign investors, has been the subject of many relevant scholarly contributions.Footnote 2 Regarding case studies, the Mexican experience has deserved probably the largest proportion of analytical and historiographical efforts (Reference BucheliBucheli 2010), but relevant comparative endeavors can also be traced (Reference Berrios, Marak and MorgensternBerrios, Marak, and Morgenstern 2011; Reference Brown, Linder and MarichalBrown and Linder 1995, Reference Brown, Linder, Topik and Wells1998; Reference Bucheli and AguileraBucheli and Aguilera 2010; Reference O’BrienO’Brien 1996; Reference Philip and SuárezPhilip 1989; Reference SánchezSánchez 1998; Reference WilkinsWilkins 1974; Reference IngramIngram 1974). Previous historical comparative studies have described the Bolivian and Mexican cases in the 1930s, the first two Latin American experiences of oil expropriations, in different analytical dimensions. Bryce Wood (Reference Wood1967) built a rich and extensive narrative of both cases in his study of the origins and development of Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy. Stephen Krasner (Reference Krasner1978) turned his attention to these cases as instances in which the US State Department successfully disputed foreign policy priorities with private companies, while Stephen Randall (Reference Randall2005) shows how these relative estrangements between state and companies were consequential for redefinitions on the structure of decision-making for US oil foreign policy. More recently, Maria Cecilia Zuleta (Reference Zuleta2011, Reference Zuleta2014) explored South American diplomatic reactions to the Mexican nationalization and the specific Bolivian perceptions of the Mexican experience.

We see the Bolivian confiscation of Standard Oil of New Jersey (SONJ) and the Mexican expropriation of eighteen foreign oil companies (including SONJ itself) as an opportunity to compare two different instances of asymmetric bilateral conflicts with a significant array of similar conditions, regarding, besides simultaneity, the starting causes of conflict (the seizure of foreign oil companies’ assets), the actors involved, and the international context. Following a most-similar-system design strategy, these similarities can be taken as constant while the analysis focuses in the differences at the level of the national political arena that we contend are an important part of the explanations for the different outcomes we identify. In the next section, we present our arguments about the similarities and differences we see in these two cases. Then, we discuss relevant features of the contrasting domestic political context in both countries, including their differing levels of state capacity. Finally, we analyze the role of domestic politics in building opportunities for the weak to advance its interest in asymmetrical environments, considering both structural enabling conditions and coalition dynamics in their construction.

Challenging Big Oil: The Mexican and Bolivian Post-nationalization Paths

The struggles around the oil industry that took place in Bolivia and Mexico in the 1930s are frequently classified as successful attempts to take full control of foreign assets in a host country (Reference Berrios, Marak and MorgensternBerrios, Marak, and Morgenstern 2011; Reference BlasierBlasier 1976; Reference GoertzGoertz 1994; Reference KrasnerKrasner 1978; Reference WoodWood 1967; Reference IngramIngram 1974; Reference Philip and SuárezPhilip 1989; Reference RandallRandall 2005). The growing importance of hydrocarbons as a primary source of energy in the world economy motivated the search by oil companies (mostly of US and British origins) to secure oil supplies in accessible areas with suitable political conditions. Host countries that initially welcomed those investors increasingly sought to improve their share in the business. As foreign companies resisted, oil rapidly became an issue on different national political agendas, and the hydrocarbons industry arose as a symbol of foreign domination.Footnote 3 Expropriation and confiscation were certainly the most drastic outcomes among other modalities of incremented control that had already been seen in other Latin American experiences, such as increasing taxes and royalties, creating national companies to compete, or securing majority shares by the state in joint ventures (Reference Berrios, Marak and MorgensternBerrios, Marak, and Morgenstern 2011; Reference GoertzGoertz 1994).

What happened in Bolivia and Mexico is often remembered as the two first relevant oil nationalizations outside the Soviet realm. In both countries, foreign companies’ assets shifted hands to government control and provided the basis for subsequent efforts to build a national oil industry. The level of development of their respective industries at the time was very different, with Mexico already an important exporter and consumer of oil (Reference Durán and WirthDurán 1985; Reference UhthoffUhthoff 2010), whereas Bolivia still had negligible levels of production and consumption (Reference KleinKlein 1964; Reference CoteCote 2016; Reference Anaya GiorgisAnaya Giorgis 2018), a fact that would affect the levels of uncertainty and ulterior political strategies and policy options available after the nationalization.Footnote 4 Although the foreign companies wanted their respective governments to intervene with coercive means and force the reversal of the measure, a diplomatic settlement was finally negotiated in both cases.Footnote 5 To be sure, there were important contextual opportunities in favor of such a drastic move: the imminence of World War II and the redesigning of US foreign policy toward Latin America according to Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor framework (Reference WoodWood 1967). Under those conditions, the State Department’s behavior was guided by a different set of goals than the ones championed by oil companies (Reference KrasnerKrasner 1978), although generally in close cooperation with them (Reference RandallRandall 2005) and, according to Maurer (Reference Maurer2013), still ultimately forced to intervene in their favor at some level despite political considerations on the contrary.

The Mexican episode should be understood in the context of a long-standing dispute over legislation that started in 1917, when a new constitution declared the national property of subsoil resources.Footnote 6 It was part of a wider political process in which the end of the Porfirio Díaz regime (1876–1911), and the revolutionary movement that came with it, opened the space for a complete renewal of political elites and the proposition of an ambitious social reformist program. Díaz’s openness toward foreign investment was perceived as excessive and harmful to national interests, and the oil industry was seen as a key area to regain control. From late 1920s, the increasing local demand for oil derivatives, in part associated with industrialization efforts, intensified political anxieties around the foreign companies commercial and labor policies (Reference UhthoffUhthoff 2010; Reference MaurerMaurer 2013). Complete nationalization was not necessarily the only solution envisaged by the different nationalist factions, but President Cárdenas decided to take that step after the oil companies’ refusal to implement a decision from the Mexican Supreme Court to improve wages and worker conditions.

The expropriation decree announced on March 18, 1938, declared the foreign oil companies’ assets to be of public utility and assured a compensation for the companies to be paid in ten years. It provoked immediate reaction and measures taken both by the companies and the US government. The US State Department delivered diplomatic notes urging the Mexican government to deliver “prompt, adequate, and effective compensation” to the companies (Reference SigmundSigmund 1980). A monthly silver purchase agreement was suspended. The Export-Import Bank refused the financing of Mexican projects. The companies attempted to boycott Mexican oil sales to the international market and to prevent it from purchasing oil equipment.Footnote 7 They also carried out a campaign to discourage tourism to Mexico (Reference SigmundSigmund 1980; Reference WoodWood 1967). But decisions on how to respond to the Cárdenas action were not unanimous in the US government. Although they recognized the sovereign right to expropriate, the companies were supported in their initial claims that Mexico should compensate immediately and that the whole issue should be submitted to international arbitration. For the companies, the preferred solution was the complete devolution of their properties and management over the Mexican oil industry, but absent this possibility, they wanted an immediate compensation that also included payment for the subsoil resources (Reference MeyerMeyer 1966), an issue at the heart of their controversy with the Mexican state since the proclamation of the 1917 Constitution.Footnote 8

But the Mexican government maintained its position and eventually succeeded in refusing immediate compensation, paying for subsoil rights, or international arbitration. After a bitter exchange of notes, by September 1938 the US government started to accept the Mexican formula suggesting the creation of a two-man commission to determine how much, how, and when the companies would receive compensation. Nevertheless, most companies, led by Standard Oil, continued to reject that formula and stated clearly to the State Department that accepting compensation “based on confiscatory valuation” would sacrifice the principle of property rights and establish a negative precedent in the defense of foreign investments (Reference WoodWood 1967, 254–255).Footnote 9

On November 19, 1941, the two governments announced an agreement to settle the oil question, along with a set of cooperation accords including financial assistance to Mexico from the US Treasury Department and the Export-Import Bank. Regarding the petroleum expropriation, the State Department lamented that negotiations with the largest US companies were fruitless (United States of America 1941).Footnote 10 Mexico made at that moment a cash deposit of $9,000,000, and the formula to determine the total amount of compensation would be set by a special commission appointed by both parties, avoiding external arbitration. As a result, on April 22, 1942, it was announced that Mexico should pay an additional $23,995,991 (plus interest at the rate of 3 percent per year dating from March 18, 1938), from which $18,391,641 corresponded to SONJ and $3,589,158 to the Standard Oil of California group (United States of America 1942). The alleged rights to compensation over subsoil resources were not recognized, and it was established that Mexico should complete all payments by 1947.Footnote 11 That way, the ten-year period established by the 1938 expropriation decree was almost fully respected.

Meanwhile in Bolivia, the March 13, 1937, caducidad decree signed by President David Toro launched a five-year dispute against the SONJ, closed in 1942 with a settlement that was similar in general terms to the Mexican one: the exit of the company would be completed after the payment of a sum negotiated by diplomatic means and followed by generous Export-Import Bank credits. But, in contrast to the generally positive appraisal of the Mexican expropriation process and settlement results, the reception to the Bolivian agreement with SONJ in 1942 has been mixed: while most foreign analysts such as Klein (Reference Klein1964), Wood (Reference Wood1967), Holland (Reference Holland1967), or Ingram (Reference Ingram1974) tend to consider it as a successful case of local diplomacy defending the country’s interests (or at least, like Blasier [Reference Blasier1972], as a middle-of-the-road compromise with grounds for satisfaction for all sides), Bolivian commentators such as Valdivieso and Salamanca (Reference Valdivieso and Salamanca1942) tend to dismiss it as an unnecessary concession to international pressures or even to classify it as high national treason as does Almaraz (Reference Almaraz1958).Footnote 12

The key difference between the cases is that in Mexico the payment of compensation, being an expropriation decree, had always been officially contemplated by the government, including the methods to determine the amounts and the period to fulfill the payments, while in Bolivia, where compensation was a forfeiture clause due to contractual breach, the official need for negotiation itself was in question. It is to this side of the matter that those who dismiss the agreement as a step back on oil nationalization normally cling. Since the forfeiture act implied that all Standard’s assets would turn to the Bolivian state, they claimed, there should be nothing else to compensate for. Because we focus on the extent to which the weakest side in a bilateral asymmetrical confrontation is able to successfully maintain its position, we consider that the Bolivians were less successful than the Mexicans in securing the nationalization in their own terms.

The 1937 Toro decree brought to an end an era of mounting resentment toward the oil giant, which exploited a clandestine pipeline to Argentina, avoiding taxes and by this fact, violating the concession contracts (Reference LozaLoza 1939; Reference Valdivieso and SalamancaValdivieso and Salamanca 1942; Reference AlmarazAlmaraz 1958; Reference KleinKlein 1964; Reference HollandHolland 1967; Reference SpencerSpencer 1996; Reference WilkinsWilkins 1974; Reference WoodWood 1967; Reference IngramIngram 1974). Additionally, public perceptions of SONJ’s noncooperative stance toward the country during the Chaco War (1932–1935) also contributed to growing local criticism of the company.

Another contrasting element is the fact that in Mexico, the whole negotiation process followed the path (though reluctantly on the companies’ part) officially laid from the start, but in Bolivia the official position after the 1937 decree and especially after the judicial ruling of 1939 was that no further issue remained, while informal attempts of negotiation had been ongoing between the country and US diplomats since at least April 1937 (Reference HollandHolland 1967, 224; Reference SpencerSpencer 1996, 111–122; Reference WoodWood 1967, 173).Footnote 13 Despite the official rhetoric, an agreement to settle the issue had been in consideration already since Toro (Reference HollandHolland 1967, 224) and continued under Germán Busch’s ensuing presidency (Reference SpencerSpencer 1996, 137–138), with the bottom line of upholding the legal validity of the confiscation decree.

As in Mexico, the US State Department was trying to bait Bolivia into a stronger alliance through economic cooperation offers in order to stave off penetration of German, Italian, and Japanese economic interests. While at first the offers tended to make the solution of the SONJ issue a prerequisite (see Reference SpencerSpencer 1996, 150, 154), the United States became increasingly impatient with the company’s stance and fearful that a protracted conflict could land capital-needy Bolivia into an alliance with the Axis powers and compromise the American war effort, thus the United States signed a cooperation agreement regarding tin sales and infrastructure projects connecting Bolivia to Chile and Brazil in 1940 (Reference SpencerSpencer 1996, 155–56).Footnote 14

By the beginning of 1942, Standard finally yielded to the pressure and acquiesced into signing a minimal settlement agreement involving a fixed-amount payment to end the dispute. Signed during the Inter-American Conference of Rio de Janeiro, it established the payment of US$1.5 million for the purchase of SONJ’s rights, interests, properties, maps, and geological studies (Reference SpencerSpencer 1996, 166).

The settlement was denounced by important actors, such as representatives from what would later become the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR) (Reference Blasier, Malloy and ThornBlasier 1971, Reference Blasier1972) or the Faculty of Law from Cochabamba University (which had voluntarily provided the country’s legal defense in the Supreme Court) (Reference Valdivieso and SalamancaValdivieso and Salamanca 1942), and the government had to face a subsequent motion of censure in parliament that narrowly failed to pass. For although the Supreme Court had used bureaucratic technicalities to avoid ruling on the core issue (see Reference Anaya GiorgisAnaya Giorgis 2018, 101; Reference IngramIngram 1974, 110), such actors considered the conflict to be resolved. And in that the agreement stated that Bolivia would be buying all of Standard’s assets with interest since the issuance of the confiscation decree, they considered that it was buying off something SONJ did not legally possess.

Building or Dissolving a Domestic Coalition: Key for Success?

Advancing foreign policy objectives, as in other domains, often depends on having a sufficient number and quality of relevant supporting political actors. This is particularly true when the issue at stake generates high levels of political confrontation among a wide array of national sectors. In the context of asymmetrical bilateral relations, it is always an option for the strongest side to try to use political and economic resources to ally with domestic political actors in order to undermine the political space for the local government to implement its defiant policies. That’s the very reason why having a broad coalition is important for the weakest side’s national government. This “broad coalition,” if possible, should not be limited to the ordinary set of actors that offer political support in matters of everyday political life. Confrontations with a foreign and stronger power often need to be supported by a set of actors larger than the normal ruling political coalition.Footnote 15

At least in the two cases we analyze here, we observed clear contrasts in the process of coalition building during their crisis with US oil companies. The Mexican government under Presidents Cárdenas and Ávila Camacho not only expanded and solidified their everyday political support base, but they were also able to attract relevant supporters for the oil issue among opposition actors. That’s why the coalition was “broad.” In Bolivia, despite the initial existence of a similar broad coalition among different actors, it soon became clear that a combination of presidential instability, incoherent leadership, and political rivalries impeded a broad anti-Standard coalition from prevailing. We highlight below the historical events that demonstrate those different paths and conclude the section by suggesting possible historical roots behind those contrasting political situations.

On the Mexican side, the building of a domestic coalition in support of the expropriation can be seen as product of a twofold process. In a first phase, we identify the careful moves that allowed President Cárdenas to reorganize the ruling coalition in order to expunge pseudoloyalists and expand its base of support among social segments. The second phase occurred as a consequence of the expropriation itself. Even if all presidents since the proclamation of the 1917 Constitution exhibited “revolutionary” credentials, there were real and deep divisions among them and their social constituencies. The Cárdenas administration (1934–1940) was a successful broker of relevant political support and loyalties to enhance his more general political project and, in particular, the 1938 offensive over the oil industry.

In this context, US-diplomats understood that using force or more drastic sanctions to revoke the expropriation would probably create a long-standing and undesirable situation of instability just south of the border. Ambassador Josephus Daniels clearly recognized it when, in a message to the secretary of state, he asserted that the expropriation was so widely supported that there was “no power under the sun that could make Cárdenas recede from his decree.” He added that even oilmen and other investors saw the inherent danger in conflict and social uprising “which they know full well would make impossible the collection of compensation of any kind” (Reference DanielsDaniels 1947, 238–239).

Such large support for the offensive against the oil companies in Mexico should not conceal that Cárdenas previously had to overcome important political challenges to consolidate his presidency. The first one came from his own party, which at the time of Cárdenas’s inauguration in 1934 was dominated by former president Plutarco Elías Calles. He had been in office from 1924 to 1928 but was still the dominant political leader in the country (Reference MedinMedin 1982). Cárdenas himself was appointed by Calles as presidential candidate for the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (PNR); therefore it was widely expected that he would be one more of Calles’s puppets. But Cárdenas made clear from the beginning that he had other plans. After rejecting the ex-president’s critiques of his friendly approach to urban worker strikes, Cárdenas fired Calles’s loyalists occupying government and military positions (Reference Hernández ChávezHernández Chávez 1979), and Calles himself was eventually accused of conspiracy and deported in April 1936 (Reference MedinMedin 1982).

With Calles out of the game, Cárdenas’s supporters won 160 of 173 seats in the legislative election of July 1937.Footnote 16 Meanwhile, unions were encouraged by the government to form the Confederation of Mexican Workers (Confederación de Trabajadores de México) and the National Peasant Confederation (Confederación Nacional Campesina). By the end of his term in 1940, almost all organized workers belonged to one of those two big organizations, implying that, after 1938, they were automatically affiliated with the ruling party of the Mexican Revolution (Partido de la Revolución Mexicana).Footnote 17 Only a few relevant unions, such as those of railway workers and electricians, kept themselves independent (Reference Hernández ChávezHernández Chávez 1979), though not necessarily in opposition to the government.

With the expropriation as a major issue dominating the political arena in 1938, Cárdenas again needed not only to secure the support of his own coalition for that drastic decision, but also, if possible, to gain the support of prominent actors from outside the social and political forces that already supported him. In this second phase of the coalition-building process, Cárdenas presented a reasonable successful record. The most relevant internal political challenge linked to the oil question came from an agrarian warlord with a strong political basis in the state of San Luis Potosí. Two months after the expropriation, General Saturnino Cedillo rose up in arms against the government. He controlled local militias and sought, without any documented success, the support from foreign oil companies (Reference GillyGilly 2001; Reference MeyerMeyer 1972; Reference WoodWood 1967). The rebellion was defeated the next year and Cedillo himself was killed during the uprising (Reference Hernández ChávezHernández Chávez 1979). In Cárdenas’s cabinet, there were also skeptical or critical voices regarding the expropriation,Footnote 18 but once the decision was announced, no opposition came from any of them.

The expropriation gained support also among prominent opposition sectors. The Catholic Church, which less than a decade before had promoted an armed rebellion against secularizing policies and during the Cárdenas-days opposed education directives (Reference Meyer and PaniMeyer 2009), offered explicit support to popular fund-raising campaigns to help pay a compensation for the companies. Indeed, most observers (the US ambassador among them) were astonished during the first anniversary of the expropriation after seeing political banners supporting Cárdenas and his party at the Metropolitan Cathedral towers in Mexico City (Reference DanielsDaniels 1947, 254). Similarly, students, scholars, and authorities from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM), who intensively resisted Cárdenas’s higher education policies (Reference GonzálezGonzález 1979), expressed their vivid support for the oil expropriation on the streets (Reference DanielsDaniels 1947, 246).

Business organizations, such as the Confederation of the National Chambers of Commerce (Concanaco), worried about an alleged excessive interventionism in oil policies but did not take concrete actions to oppose that decision. In public, the Concanaco bulletin avoided direct criticisms. Indeed, it recognized the widespread support from different social sectors and praised Cárdenas for saving the “national honor” by warranting compensation to the companies.Footnote 19

To be sure, two years after the expropriation, the 1940 general election brought to the political arena relevant opposition actors who backed the Juan Andrew Almazán bid for president. He conquered considerable support among middle-class urban sectors, business groups, and conservative political movements reacting to the “cardenista experiment” (Reference Knight, Brown and KnightKnight 1992). But the oil expropriation was not an important issue during the campaign (Reference MedinaMedina 1978). Having consolidated a broad coalition around the expropriation, the space for an effective foreign intervention to neutralize oil Mexican policies under Cárdenas was thus reduced.Footnote 20

In contrast to Mexico, Bolivia’s ability to build a sustainable and heterogeneous coalition by the leaders who confronted SONJ was undermined by a set of zigzagging moves, contradictions, and disputes between actual and potential supporters. Colonel Toro was installed as president leading a coalition depending fundamentally on the armed forces’ backing and the moral ascendancy of war hero Germán Busch (Reference KleinKlein 1965, Reference Klein1967), which started the period known as Socialismo Militar (Military Socialism), modeled implicitly and explicitly on the Mexican revolution and especially on Cárdenas’s experience since 1934 (Reference StefanoniStefanoni 2015, 275).

In many senses a ragtag coalition guided more by moral outrage toward the oligarchic system that led the country to a bloody fiasco than by a programmatic set of reforms, the Military Socialism experiment proceeded with severe power disputes between the parties in its support base. Originally, the new regime was sustained by the young officers and veterans organized in the Legion of Ex-Combatants, the middle-class reform-oriented Socialist Party led by Toro’s first foreign minister Enrique Baldivieso, and the newly rebranded Socialist Republicans led by former president Bautista Saavedra (Reference KleinKlein 1969, 228). The regime was also supported on the fringes by trade unions and small Marxist-oriented groups clustered around Toro’s first minister of labor, Waldo Alvarez (Reference KleinKlein 1965, 38, Reference Klein1969, 236–237; Reference StefanoniStefanoni 2015, chap. 8), and even the traditional right-wing parties (Liberal and Genuine Republican) initially announced their acquiescence to the new regime (Reference KleinKlein 1969, 231).

Though the army’s key figure was Lieutenant-Colonel Busch, his self-admitted lack of intellectual refinement led him to appoint Toro as president after the coup that ousted Tejada Sorzano in May 1936 (Reference KleinKlein 1965, 32, Reference Klein1967, 167, Reference Klein1969, 229–230; Reference StefanoniStefanoni 2015, chaps. 8–9). But Busch—and with him the Legion of Ex-Combatants and the army—became increasingly weary of the infighting among members of the young and heterogeneous ruling coalition. The move against SONJ in March 1937 was then part of Toro’s effort to strengthen his base of support in the context of Busch’s growing impatience with the erratic pace of social change (Reference KleinKlein 1965, Reference Klein1967; Reference SpencerSpencer 1996; Reference Anaya GiorgisAnaya Giorgis 2018; Reference AlmarazAlmaraz 1958; Reference HollandHolland 1967).

Toro then tried to organize a more stable and autonomous base of support with initiatives to create an official Partido Socialista del Estado (State Socialist Party). With cabinet members sent across the country to set up committees and the adhesion of former Baldivieso-Socialists, the party already had an embryonic national committee and Bolivia’s first national labor confederation (Confederación Sindical de Trabajadores de Bolivia) was seriously considering bringing organized labor into the fold. But in contrast to Cárdenas’s successful initiatives to secure command in Mexico, Toro’s effort was stillborn, as Busch moved on July 10 to take the presidency into his own hands (Reference KleinKlein 1965, 50–51, Reference Klein1967, 168, Reference Klein1969, 263–266; Reference StefanoniStefanoni 2015, 288–289).

Busch had to deny speculations that he had been financed by Standard’s interests and assured that he would continue Military Socialism’s legacy. Like Toro, he’d also try to establish a state-sponsored Socialist Party, but with a lack of commitment that would bewilder and disappoint supporters (Reference KleinKlein 1967, 173–174), while the pre-Chaco War parties regrouped as Concordancia. Still exasperated by the growing internal dissent, Busch announced in April 1939 he would henceforth govern as dictator and, instead of trying to broaden his support base, he confined himself to the army and the Legion of Ex-Combatants. In marked contrast to Cárdenas’s organizing actions, Busch was incapable of recognizing his internal adversaries even in the military, appointing as army commander in chief the conservative and politically astute General Carlos Quintanilla and allowing him to purge the more radical younger officers (Reference KleinKlein 1967, 173). The state bureaucracy was also still amply controlled by stalling conservatives connected to the tin oligarchy, and exasperated by the lack of progress on the decreed policies, Busch committed suicide on August 23 (Reference KleinKlein 1967, 182; Reference Anaya GiorgisAnaya Giorgis 2018, 110) and was succeeded by Quintanilla.Footnote 21

Despite initial promises, the brief Quintanilla government effectively ended the Military Socialism experiment with the support of Concordancia (Reference KleinKlein 1969, 328). The election of General Enrique Peñaranda in 1940 initially appeared as the renewal of a broad coalition including both the moderate left descending from former Baldivieso-Socialists and the Concordancia. But with the pro-USA inclinations of Peñaranda and the dismantling of Busch’s economic program (Reference KleinKlein 1969, 337), those leftist groups quickly abandoned the government and joined other Marxist and socialist groups with a solid presence in Parliament. Together, they were still strong enough to maintain the anti-Standard agenda, at least to the point of adjourning indefinitely a deliberation about a presidential request to authorize the negotiation of a final settlement with SONJ (Reference WoodWood 1967, 192).Footnote 22

In tandem with these congressional battles, the US government, fearful of Nazi influence in Bolivian politics, paved the way to establish cooperation instruments with La Paz, including the signing of a small lend-lease package of credits and military materiel and the sending of a mission to outline further cooperation possibilities (Reference HollandHolland 1967; Reference SpencerSpencer 1996; Reference WoodWood 1967). Meanwhile, Peñaranda decided to circumvent the internal opposition and present a fait accompli, by signing and publishing as supreme decree the agreement reached with SONJ in Rio (Reference SpencerSpencer 1996, 166–169; Reference WoodWood 1967, 197–200). The legislative opposition then proposed—and narrowly failed to approve—a censure motion in November 1942 (Reference WoodWood 1967, 200). In little more than one year, the president would be ousted in a coup that put Major Gualberto Villarroel in the presidency.Footnote 23 The president’s policies toward Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) after the agreement, with the stripping of its funds and the deportation of its director and former minister of petroleum under Busch, Dionisio Foianini (Reference CoteCote 2016, 114), certainly did not help his case.

In sum, the main real action toward the goal of broadening a coalition in Bolivia came with Toro’s Partido Socialista del Estado effort, but it was undermined by Busch’s intervention and ulterior lack of interest in the matter. Thus whatever anti-Standard coalition could have been built to support the Bolivian stance during the negotiation process splintered during the five years between Toro’s decree and Peñaranda’s settlement agreement. An additional difficulty was brought by the stark change in programmatic orientation since Quintanilla. During the period Bolivia had four different presidents, all of them men of arms and only one elected, who governed for an average of only 692 days under different statuses—constitutional, provisional, dictatorial, with or without an empowered Congress, and so on—and with different and contradictory ideological orientations.Footnote 24

The two countries also presented a stark contrast in their structural levels of state strength. While Mexico was on the path of consolidating its new institutions after a full-fledged revolution, Bolivia was amid an extremely volatile context of social and political change shortly after the end of a devastating war. It was still unclear who “deserved” to participate, and to many (e.g., Reference KleinKlein 1969; Reference MalloyMalloy 1970; Reference Whitehead, Grindle and DomingoWhitehead 2003) it represented the opening of a critical juncture that would lead to the 1952 revolution, preceded by a series of short-lived governments and coups. Instability also dominated the oil sector, which, after the Davenport Code of 1955, soon became open to foreign investment and controlled by another US firm (Gulf Oil) only to be nationalized again in 1969 (Reference KleinKlein 1964; Reference RadmannRadmann 1972; Reference Klein and Peres-CajíasKlein and Peres-Cajías 2014; Reference KaupKaup 2015; Reference CoteCote 2016; Reference YoungYoung 2017; Reference Anaya GiorgisAnaya Giorgis 2018).

These contrasting situations in both countries can also be read in consideration of recent voices calling attention to the necessity of treating the state as a variable and to the long-lasting consequences of Latin America’s specific legacies of state formation and differing levels of consolidation (e.g., Reference OszlakOszlak 1981; Reference Centeno and FerraroCenteno and Ferraro 2013; Reference CentenoCenteno 2014). The comparative study of Marcus Kurtz (Reference Kurtz2013), particularly, stresses the importance of the absence of servile labor relations, intra-elite cooperation and the timing of political incorporation of nonelite sectors of society. Though his case studies are Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, the trajectory of Bolivian state formation fits nicely with the chronically weak Peruvian state, with servile relations in the countryside (also widespread in some other sectors) still predominating in Bolivia through the whole nationalization process (and beyond), and its (very small) middle classes incorporated since its first party system in the nineteenth century (see Reference IrurozquiIrurozqui 1994; Reference Cunha FilhoCunha Filho 2018).

Mexico, with its 1910–1917 revolution, had experienced an extensive political and social rearrangement that included the struggle against servile labor schemes that predominated in rural properties in the early twentieth century, and opened relevant legal channels for working-class incorporation in higher levels of social and political life. The creation of the National Revolutionary Party in 1929, of which Cárdenas was a member, effectively served the purpose of creating an institutional platform for cooperation and power sharing among different revolutionary factions. At the time of expropriation, under such conditions, the Mexican political arena had already left behind its more unstable days and set forth a successful process of state refoundation, providing the institutional basis for decades to come. In Bolivia, in contrast, post-Chaco social and economic distresses led to a much more unstable and undefined political landscape, which certainly hindered the possibilities for a broad anti-Standard coalition to take hold.

Concluding Remarks

We have analyzed the historical experiences of oil nationalization in Bolivia and Mexico in the 1930s from a comparative perspective as a mean to explore significant features of asymmetrical nonviolent disputes in international politics. Relying mostly on existing historiographical accounts, we not only reviewed the processes of nationalization and their implications for bilateral relations with the United States, but we also described how relevant domestic political actors behaved to support, or oppose, the defiant move of the executive branch toward stronger foreign interests.

We showed that at the level of domestic politics, there was a stark contrast in the strength and duration of the coalitions behind the defiant side. While in Mexico a broad and heterogeneous coalition supported Cárdenas’s oil policy, in Bolivia there was a much more fragmented and unstable scenario in which the initial strength in favor of Toro’s decree was lost due to structural state deficiencies and leadership issues. We contend that this aspect of the overall political process of asymmetrical bilateral confrontations should be taken into consideration to understand their outcomes. In other words, the Mexican government was able to expropriate foreign companies on its own terms, not only because of favorable conditions found in the international environment, but also because of the strength and scope of its domestic coalition and its much more solid state institutions. In contrast, the anti-Standard coalition in Bolivia was unable to maintain control over the presidency and major actors ended up considering the agreement as a step back.

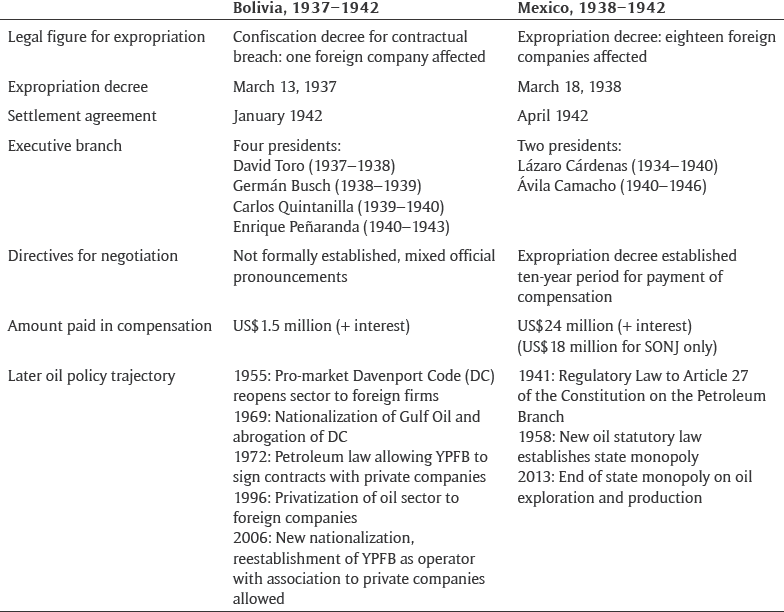

At that level, our study observed significant contrasts in both cases regarding the stability of power holding in the executive branch, and the extent to which the defying bid was supported by a consistent, broad coalition that includes segments of opposition groups willing to sustain the current government on this particular issue. In Mexico, two presidents from the same party, Lázaro Cárdenas and Ávila Camacho, were involved in the process with no significant differences regarding the way they conducted negotiations. In Bolivia, the period encompassed four presidential mandates that were all quite ephemeral (see Table 1), came to power through different channels, responded to different and changing sets of social and institutional restraints, and did not follow one overall orientation but were rather contradictory among one another. Regarding the strength of a coalition against foreign companies among domestic actors, the ability of the Mexican leaders to gain consensus among a very diverse set of social and political segments contrasted with the Bolivian fragmentation and instability that eventually produced the internally contested 1942-settlement with SONJ.

Table 1 Nationalization sequences in contrast.

With hindsight, one can say that Cárdenas’s internal reorganization decisions and achievements paved the way for the long path of stability in the power structures of Mexican politics for decades afterward, a record that contrasted markedly with the inability of Bolivian Military Socialism to do the same despite conscious and self-acknowledged attempts to emulate the Mexican Revolution and Cárdenas’s leadership. We must nevertheless recognize that Mexico was in the process of consolidating its new institutions after the reorganizations brought about by the revolution a couple of decades earlier. Considering the oil question specifically, the essentials of the industry’s reorganization in the absence of the biggest foreign oil companies were maintained until the very recent reforms approved in 2013. Bolivia, however, started its nationalization process during the beginning of a hotly contested period in which the old order was crumbling without a clear picture of what would come next, quite similar in various ways to at least the first two decades of the Mexican Revolution. Interestingly, the oil question was already present during the revolutionary days in Mexico, but expropriation had not been seriously contemplated then because early revolutionary governments “were overwhelmingly concerned with establishing their own political legitimacy” (Reference Durán and WirthDurán 1985, 181). As mentioned, Bolivian instability would last for a decade longer after the settlement agreement with SONJ and even beyond, extending in many ways into Bolivia’s “uncompleted revolution” (Reference MalloyMalloy 1970) of 1952.

Theoretical efforts to better understand how similar units of the international system behave differently and have contrasting outcomes when confronted with similar international situations have already stressed the need to turn attention to what happens in domestic politics. Nevertheless, they often limit their observations to the preferences of key decision-makers, setting aside the dynamics of coalitions that allow political elites and governments to strengthen their positions within the domestic arena or the enabling conditions which make them possible. Having shown that contrasting outcomes in the Bolivian and Mexican cases of asymmetrical bilateral nonviolent disputes in the 1930s seem connected with the abilities and conditions necessary to build a broad and heterogeneous domestic coalition is, of course, not a sufficient empirical basis to support a general proposition. But we believe that the comparison lends support to the hypothesis that state strength and domestic coalitions are crucial for the success of the weakest part of a bilateral conflict, which should be further tested with a broader set of cases, historical circumstances, and issue areas.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gustavo Rodríguez, Maude Forté, and Franco Canek Pérez Flores for their invaluable help on getting access to important material used in this research.