Introduction

Contemporary societies are faced with multiple ecological and social crises. The ecological crisis continues to be persistent and alarming with transgressions of six out of nine planetary boundaries critical for environmental functions and life-support systems (Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Steffen, Lucht, Bendtsen, Cornell, Donges, Drüke, Fetzer, Bala, von Bloh, Feulner, Fiedler, Gerten, Gleeson, Hofmann, Huiskamp, Kummu, Mohan, Nogués-Bravo, Petri, Porkka, Rahmstorf, Schaphoff, Thonicke, Tobian, Virkki, Wang-Erlandsson, Weber and Rockström2023), and with global temperatures heading towards 3 degrees Celsius by the end of the century (IPCC Reference Lee and Romero2023). From a social perspective, the huge and increasing income and wealth inequalities all over the world signify the social crisis (e.g., Chancel et al. Reference Chancel, Piketty, Saez and Zucman2021), threatening not only public health but also political stability and democratic institutions due to the erosion of social cohesion and trust (Pickett and Wilkinson Reference Pickett and Wilkinson2015; Stiglitz Reference Stiglitz2012). These crises are linked and tend to amplify each other, as exemplified by wealthy individuals contributing disproportionately to greenhouse gas emissions and where the poorer and more vulnerable strata of society contribute the least while also having the least resources to cope with the consequences of climate change (see e.g., Chancel et al. Reference Chancel, Bothe and Voituriez2023). Still, contemporary societies tend to be organized along a silo-based logic of two separate social welfare and environmental agendas, a logic that is ‘detrimental to society’s capability to properly understand and address its relation to the – seemingly increasingly strained – natural environment’ (Fischer-Kowalski Reference Fischer-Kowalski and JD2015, 254). Instead, an eco-social agenda is assumed to better handle both the drivers and the consequences of these crises. There is thus a need for urgent social-ecological transformations that take both social and ecological dimensions of sustainability into account, an ambition captured in the emerging concept of ‘sustainable welfare’ emphasizing the dual focus of securing social wellbeing and human needs while respecting ecological limits (e.g., Koch and Mont Reference Koch and Mont2016).

Social-ecological transformations of the magnitude needed are in most open and democratic societies dependent on public support for, but also on the public’s active engagement in political action aimed at societal change towards, sustainable welfare. Politics is thus assumed to follow the public (e.g., Eikert Reference Eikert, Merkel, Kollmorgen and Wagener2019; Svallfors Reference Svallfors and Svallfors2012; Van Deth Reference van Deth2014). The focus on civil society is also highly evident in green political thinking, where deeper forms of social-ecological transformations are expected to emanate from civil society along with the mobilization of citizens and affected communities which, in turn, is thought to foster a sense of responsibility to act in response to environmental change and social injustices (Eckersley Reference Eckersley2004).

When it comes to previous research on public attitudes and political action, the two research fields tend not only to be separated but also to follow a logic of separate social welfare and environmental agendas (see however Emilsson Reference Emilsson2022; Fritz and Koch Reference Fritz and Koch2019, regarding eco-social attitude patterns). In this article, we aim to overcome these divisions by exploring the relationships between public support and political action performed by the public in the strive towards sustainable welfare. For instance, are individuals supportive of an eco-social agenda also actively involved in various modes of political action to prevent climate change and to promote social justice and welfare? The exploration of these kinds of relationships will reveal a more comprehensive and complex picture of the public in times of urgently needed social-ecological transformations.

In this article, our primary objective is to explore how public attitudes related to an eco-social agenda are interlinked with political action aimed at preventing environmental change and promoting social welfare. We are also interested in understanding who the individuals are – in terms of their sociodemographic characteristics and political values – that express certain types of attitudes and engage in various modes of political action. This gives us the opportunity to also study similarities and differences between groups of individuals that think and act differently regarding issues related to an eco-social agenda. By means of multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) and cluster analysis we are able to explore and visualize these linkages, but also to identify lines of political tension and conflict as well as possible support for social-ecological transformations.

In our study, we focus on public attitudes and political action in Sweden; a well-established welfare state in which residents to a large extent are concerned about both welfare and environmental issues (Fritz and Koch Reference Fritz and Koch2019; Gaffney et al. Reference Gaffney and Zoe Tcholak-Antitch2021; Otto and Gugushvili Reference Otto and Gugushvili2020). The Swedish context is defined by comparatively universal welfare arrangements and progressive environmental policies (Blomqvist and Palme Reference Blomqvist and Palme2020; European Commission 2022). While the country’s ecological footprint is still among the highest in the world (O’Neill et al. Reference O’Neill, Fanning, Lamb and Steinberger2018), Sweden is an established environmental state with a well-developed and institutionalized environmental governance regime (Duit Reference Duit2016; Hildingsson and Khan Reference Hildingsson, Khan, Bäckstrand and Kronsell2015). Sweden also provides constitutional arrangements such as freedom of expression, assembly, and association, that are favourable for political action (Pierre Reference Pierre2015). Taken together this makes Sweden a critical case (Flyvbjerg Reference Flyvbjerg2006) in exploring the links between eco-social attitudes and modes of political action aimed at preventing environmental change and promoting social welfare.

The article proceeds as follows. In the next section, we review previous research on attitudes related to an eco-social agenda and the interlinkages between attitudes and political action. This section also covers a discussion about various modes of political action and who generally participates in political action. Subsequently, we describe the data and methods. Thereafter the results are presented together with a discussion about the relationship between eco-social attitudes and various modes of political action. Finally, we discuss the implications of our study in the wider perspective of social-ecological transformations.

Previous research

Just as eco-social divides are deeply ingrained in our societies, so is the case also in research where the differentiation and specialization in various social and environmental disciplines and fields are highly evident. As shown in the literature review below, only recently has research on public attitudes started to overcome the divide, while research on political action still is divided to a large extent.

Eco-social attitudes

The traditional research on public attitudes with respect to environmental policy and social welfare concerns follow a clear divide between, on the one hand, environmental attitudes and, on the other hand, welfare attitudes. Being based on a rich and well-established literature respectively, environmental attitudes often pertain to ecological concerns or environmental policies (see e.g., Cruz and Manata Reference Cruz and Manata2020; Fairbrother Reference Fairbrother2022), whereas welfare attitudes can refer to overarching concepts such as ‘equality’, ‘redistribution’, ‘the public sector’, or to specific social welfare policy preferences or evaluations (Kumlin et al. Reference Kumlin, Goerres, Spies, Béland, Kimberly, Obinger and Pierson2021). Building on the premise that social-ecological transformations would benefit from greater compatibility between social and environmental policies, a handful of studies have investigated the intersection between social and environmental attitudes (e.g., Emilsson Reference Emilsson2022; Fritz and Koch Reference Fritz and Koch2019; Jakobsson et al. Reference Jakobsson, Muttarak and Schoyen2018; Otto and Gugushvili Reference Otto and Gugushvili2020). Much of this research has focused on studying the potential conflict or synergy between welfare and environmental attitudes. Whereas some studies investigated the trade-offs between welfare and environmental attitudes (Armingeon and Bürgisser Reference Armingeon and Bürgisser2021; Jakobsson et al. Reference Jakobsson, Muttarak and Schoyen2018), others have focused on both synergy and conflict patterns (Fritz and Koch Reference Fritz and Koch2019; Otto and Gugushvili Reference Otto and Gugushvili2020). In some of the latter studies a four-fold typology of eco-social attitudes has been developed, which consists of (1) a synergy pattern in which individuals express joint support for social welfare and environmental concerns, (2) a red crowding-out pattern where individuals express relatively high support for social concerns but relatively low support for environmental concerns, (3) a green crowding-out pattern where individuals express relatively high support for environmental concerns but low support for social welfare, and (4) a rejection pattern in which individuals express little or no support at all for both concerns. Even though previous studies have indicated who these individuals are in terms of sociodemographic and socio-economic characteristics, political orientation, and so forth (Emilsson Reference Emilsson2022; Otto and Gugushvili Reference Otto and Gugushvili2020), it is still unknown who is active in, sympathetic to or reluctant to various modes of political action.

Political action in relation to social and environmental dimensions

In traditional research on political action, the social-ecological divide is apparent in that, for instance, environmental political action and environmental movements are treated as separate environmental sub-genres (Dalton Reference Dalton2015; Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni and Grasso2015; Marquart-Pyatt Reference Marquart-Pyatt2018), within which various topics are being addressed, such as nature conservation, nuclear energy opposition, animal rights, and more recently climate change (Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni and Grasso2015). When it comes to social dimensions, the focus on topics, such as labour, feminism, or disability, provides ground for being categorized as movement sub-genres in themselves (della Porta and Diani Reference della Porta and Diani2020; Moghadam Reference Moghadam, Baksh and Harcourt2015). Even though the social and environmental dimensions in the political action and the social movement literature tend to be separated, the bridging of the two dimensions is not totally absent, however. For instance, in the environmental justice movement, the intersection between distributive justice and environmental impacts is key (Purdy Reference Purdy2018).

With the intention of ‘affecting politics’ (van Deth Reference van Deth2014, 351) a diverse action repertoire is evident in different kinds of movements, irrespective of them being classified as social or environmental (e.g., Dalton Reference Dalton2015; della Porta and Diani Reference della Porta and Diani2020; Taniguchi and Marshall Reference Taniguchi and Marshall2018). In a conceptual map developed by van Deth (Reference van Deth2014; see also Ohme et al. Reference Ohme, de Vreese and Albæk2018; Theocharis and van Deth Reference Theocharis and van Deth2018), various modes of political action have been distinguished, notably the following: ‘institutional forms of political action’, which includes activities taking place in the political sphere (e.g., organizational membership, donating money); ‘non-institutional forms of political action’, which are targeted at the political sphere (e.g., signing a petition, demonstrating, protesting, and civil disobedience), and ‘lifestyle politics’, which are non-political but politically motivated activities (e.g., energy-saving actions, not eating meat). In addition, ‘digitally networked participation’ has recently emerged as another form of political action (Theocharis et al. Reference Theocharis, de Moor and van Deth2019). These four modes of political action all have their role to play in societal transformations, whether to influence established political institutions, to challenge dominating structures and patterns, to mobilize popular support or protests, or to foster a civic culture of lifestyle politics (cf. Caniglia et al. Reference Caniglia, Brulle, Szasz, Dunlap and Brulle2015; Eikert Reference Eikert, Merkel, Kollmorgen and Wagener2019).

Such a broad repertoire of political activities can be seen against a shift from traditional forms of electoral participation in terms of voting towards more active and direct forms of political action, such as signing petitions, buying products for political or ethical reasons, protesting, and posting in social media (Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2010; Theocharis et al. Reference Theocharis, de Moor and van Deth2019). In reaction to alarmist shoutouts about the decline in political participation, Dalton (Reference Dalton2008) stressed that political and democratic action has even expanded and become enriched. This has been described as a shift from ‘duty based’ to ‘engaged’ forms of citizenship (Dalton Reference Dalton2008). Empirical studies show, however, that only a relatively small share of individuals take part in more active and direct forms of political action (e.g., Klandermans Reference Klandermans, DA, della Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013; Saunders and Shlomo Reference Saunders and Shlomo2020). Moreover, research on political action targeted at environmental issues has found that both institutional and non-institutional modes of action have decreased while lifestyle politics seem to have increased (Dalton Reference Dalton2015; Marquart-Pyatt Reference Marquart-Pyatt2018). However, the global climate strikes in 2019 showed that non-institutional political action is still highly present, as thousands of individuals mobilized to the streets (de Moor et al. Reference de Moor, Uba, Wahlström, Wennerhag and De Vydt2020).

Links between attitudes and political action

It has been argued that the ‘shift in modes of political engagement is often linked to changing political values’ (Grasso and Giugni Reference Grasso and Giugni2018, 472), especially so in terms of an increase in post-material values in affluent and advanced democracies (Inglehart and Catterberg Reference Inglehart and Catterberg2002). Studies have shown that values related to post-materialism are linked to protest participation (Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2010; Welzel and Deutsch Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012), but also to environmental action such as membership in environmental organizations (Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2010; Taniguchi and Marshall Reference Taniguchi and Marshall2018).

The link between public attitudes and political action is also evident in the literature on ecological citizenship (e.g., Dobson and Bell Reference Dobson and Bell2006; MacGregor Reference MacGregor and van der Heijden2014). This research has studied variation in values, beliefs, and motivations for environmental behaviour, explained by attitudes associated with an ecological citizenship ideal and derived from a sense of moral responsibility to act and lead one’s life in a sustainable manner in order to minimize one’s ecological impacts (Jagers Reference Jagers2009). Empirically, this literature has established that individuals with pro-environmental attitudes are more likely to also act in an ecologically responsive way in their everyday lives as a means of lifestyle politics (Jagers et al. Reference Jagers, Martinsson and Matti2014).

Attitudes also play a role in political action from a broader perspective. Previous research has shown that the kind of political action performed depends on the type of political values and attitudes individuals hold (Grasso and Giugni Reference Grasso and Giugni2018; Welzel and Deutsch Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012). Progressive and emancipative values, for instance, tend to increase the likelihood of participating in non-institutional political action such as protesting. As such, individuals who express support for economic redistribution tend to engage in both non-institutional and institutional political action such as protesting and joining organizations. One reason for this varied political participation might be that ‘their political beliefs and their distaste for inequality are likely to provide strong motivations to engage politically in order to change the current institutions’ (Grasso and Giugni Reference Grasso and Giugni2018: 480). Regarding institutional political action, it is assumed that the same individuals desire state intervention to tackle distributional inequality, while organizational embeddedness can be seen as means of advocacy. Another study showed that a broader conception of politics – i.e., a fair number of acts being perceived as political – makes people more likely to engage in political action (Görtz and Dahl Reference Görtz and Dahl2020). The wider the conceptualization of politics that people have, the more topics and issues they care about; ‘when people want to change society for the better and also perceive that many aspects are open for change, or even wrong, they have more aspects to […] engage with through political action’ (Görtz and Dahl: 5).

Studies investigating the effects of attitudes on various modes of political action often assume a causal relationship. This assumption has been challenged, however. For instance, Weinschenk and colleagues (2021) showed that the relationship is confounded by familial factors and concluded that ‘attitudes and participation may be correlated not because they are causally related but instead because both are driven by common factors such as personality traits’ formed in the early life phases (Weinschenk et al. Reference Weinschenk, Dawes, Oskarsson, Klemmensen and Nørgaard2021: 6). Others have shown that it is even more likely that political participation has an impact on attitudes rather than the other way around (Quintelier and van Deth Reference Quintelier and van Deth2014; de Moor and Verhaegen Reference de Moor and Verhaegen2020). One study, for example, showed that ecological concerns are channelled through lifestyle politics such as efforts to save energy, vegetarian diets, etc. (de Moor and Verhaegen Reference de Moor and Verhaegen2020). In this article, we are interested in exploring the relationships between eco-social attitudes and political action without either methodological pre-assuming or determining the effects of one on the other.

Who engages in political action?

Numerous studies have investigated who becomes involved in political action in terms of socio-economic, sociodemographic, and political ideology characteristics. Even though such characteristics might be different for various modes of political action, some general trends can be distinguished in established democracies across social and environmental movements. One such trend is the so-called ‘social-status participation gap’ (Dalton Reference Dalton2017), which indicates that there are differences in political participation due to socio-economic status. Higher status, particularly higher educational attainments but also higher incomes and occupational positions, tend to increase engagement in political action. This is because higher status is linked to greater amounts of resources such as time, money, and access to information that facilitate political participation (ibid., see also Marien et al. Reference Marien, Hooghe and Quintelier2010; Lane et al. Reference Lane, Thorson and Xu2023; Saunders and Shlomo Reference Saunders and Shlomo2020). Participation in political protests, however, depends on the type of demonstration: while, for instance, demonstrators in May Day marches tend to identify themselves as working class (Hylmö and Wennerhag Reference Hylmö, Wennerhag, Giugni and Grasso2015), demonstrators in environmental protests tend to be university-educated people with middle-class occupations (Wennerhag and Hylmö Reference Wennerhag, Hylmö, Giugni and Grasso2021).

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, older individuals tend to be more engaged in partisan activities, such as voting and political party membership, whereas younger individuals seem to be more engaged in active and direct forms of political action such as protesting, political consumerism, and digitally networked participation (e.g., Dalton Reference Dalton2017; de Moor et al. Reference de Moor, Uba, Wahlström, Wennerhag and De Vydt2020). In terms of gender, the results are rather mixed. Some studies found women to be more engaged in non-institutional political action such as protesting and boycotting (Coffé and Bolzendahl Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010; Marien et al. Reference Marien, Hooghe and Quintelier2010), as evident in the global climate strikes in 2019 (de Moor et al. Reference de Moor, Uba, Wahlström, Wennerhag and De Vydt2020). Another study, however, found no gender differences in boycotting while men were slightly more likely to attend demonstrations (Gallego Reference Gallego2008). Moreover, it has been shown that a political left-wing orientation is associated with political action in general, but not with voting (Dalton Reference Dalton2017). This is particularly the case when it comes to non-institutional modes of political action such as protesting and political consumerism (e.g., Copeland and Boulianne Reference Copeland and Boulianne2022; Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2010; Saunders and Shlomo Reference Saunders and Shlomo2020; Taniguchi and Marshall Reference Taniguchi and Marshall2018).

Studies on ecological citizenship have come to similar findings regarding factors such as gender, age, income, education, and political orientation. The typical ecological citizen in Sweden, for example, is identified as a young, middle-class, well-educated, female person living in a larger urban setting with high trust in politicians, centre-to-left-leaning ideological preferences, and membership in environmental, humanitarian, and cultural organizations (Jagers Reference Jagers2009; Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Max Koch, Emilsson, Hildingsson and Khan2021; see Zorell and Yang Reference Zorell and Yang2019, and Novo Vázquez and García-Espejo Reference Novo Vázquez and García-Espejo2021, for similar findings in other contexts).

In sum, this short overview indicates many links between attitudes, social positions, and various modes of political action. Our study aims to explore what these links look like specifically for the case of eco-social attitudes and political actions to prevent environmental change and promote social welfare.

Data and methods

The data for this study were collected in a citizen survey conducted in the research project The New Urban Challenge? Models of Sustainable Welfare in Swedish Metropolitan Cities’ (funded by the Swedish Research Council FORMAS). It was fielded from January 2020 to April 2020. A stratified random sampling strategy was used, targeting 5000 Swedish residents in the age group 18–84 years. Because of the research project’s urban focus, the stratification was made in order to target residents living in Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmo as well as those living in Sweden at large. With four equally large strata (n = 1250), the stratified sample was disproportionate in overrepresenting cities. A total of 1529 individuals responded to the survey, giving an overall response rate of 31%. In order to allow for statistical generalizations from the sample to the Swedish population at large, and to adjust for the disproportionate allocations, a sample weight was created and applied in the descriptive statistics (see the online supplementary material for both weighted and unweighted results, Tables A–C, Supplementary material). Moreover, a post hoc nonresponse analysis indicated a slight overrepresentation of older respondents as well as respondents with higher education and incomes in the sample, indicative of the ‘middle class bias’ in survey studies (Goyder et al. Reference Goyder, Warriner and Miller2002).

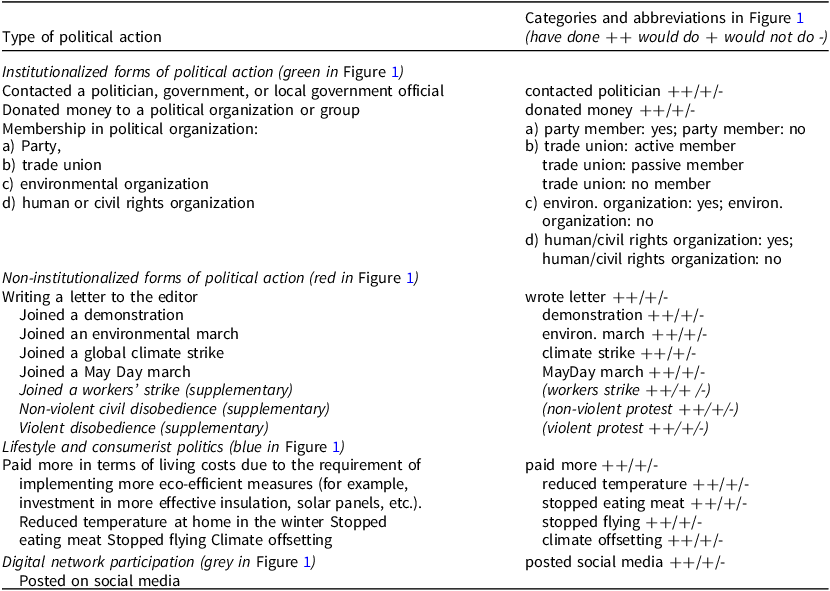

In operationalizing the four modes of political action as discussed in the previous section – institutionalized political action, non-institutionalized political action, lifestyle politics, and digital network participation – 20 items in the survey questionnaire were used (see Table 1). Membership in a political organization was asked in the following way: ‘If you have been involved in any of the following types of organizations in the past 12 months, please indicate whether you are a passive or an active member’. All other types of political action were enquired in the following survey question: ‘There are many different things people can do to prevent climate change and promote societal change. Which of the following things have you done during the last 12 months? If you have not done anything, what could/would you possibly do or not do?’ The response categories were the following: ‘Have done during the last 12 months’, ‘Could possibly do’, and ‘Would not do’. See further, Tables A and B in the supplementary material for the shares of respondents in each of these three response categories, including refusals, with respect to the 20 political action items.

Table 1. Summary of items measuring political action and how they are included in the analysis

With inspiration from previous research on the emergent field of eco-social attitudes (e.g., Fritz and Koch Reference Fritz and Koch2019; Otto and Gugushvili Reference Otto and Gugushvili2020), we operationalized the eco-social attitudes in this article through 35 items that captured various aspects of social welfare and environmental policies and concerns. To identify the latent structures within these attitudes and to construct a composite measure, we applied principal component analysis that yielded two dimensions (welfare support and ecological consciousness). Using these, we distinguished the following four types of attitudes: ‘synergy’ (above-average welfare support and ecological consciousness), ‘red crowding-out’ (above-average welfare support, below-average ecological consciousness), ‘green crowding-out’ (above-average ecological consciousness, below-average welfare support), and ‘rejection’ (below-average welfare support and ecological consciousness). See supplementary material for more details regarding the operationalization strategy and for the shares of respondents in each of the four attitude types (Table C).

In order to explore the relationships between various modes of political action and eco-social attitudes, we conducted an MCA which is an exploratory dimension-reduction technique that analyses contingency tables of categorical data (Greenacre and Blasius Reference Greenacre and Blasius2006; Hjellbrekke Reference Hjellbrekke2019). MCA is also suitable to visualize relations between variables, eco-social attitudes and modes of political action in this case, within graphical representations. All of our variables – membership in organizations, participation in political action, and type of eco-social attitude – were categorical variables and included as active variables in the analysis.Footnote 1 Three of the political actions that have very low frequencies on the ‘have done’ modalities were included as supplementary variables, namely violent protests, non-violent protests, and joining workers strikes (see Table A in supplementary material).

In the last step, we ran an agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis with Euclidean distances and the Ward criterion on the results of the MCA (Jaeger and Banks Reference Jaeger and Banks2023). In addition to exploring the interdependencies between variables through MCA, the cluster analysis allows to classify respondents into groups regarding their eco-social attitudes and political actions as well as to study the groups by comparing their socio-political profiles. We used the FactoMineR package in R to conduct the MCA and the cluster analysis (Lê et al. Reference Lê, Josse and Husson2008). Also, the missMDA package (Josse and Husson Reference Josse and Husson2016) was used to impute missing values by performing principal components methods on the incomplete data following the missing at-random assumption.

Results and discussion

MCA was applied to the 18 active variables of political action and eco-social attitudes, altogether involving 52 categories. This led to 52 – 18 = 34 latent dimensions. The first two dimensions are most relevant for the interpretation of the data (see Figure A in the supplementary material). The eigenvalues and explained variances of the dimensions were rescaled according to Hjellbrekke (Reference Hjellbrekke2019: 36f.), who suggests that dimensions with eigenvalues lower than 1/Q (Q = number of variables) should be omitted from the calculation. In our case, dimensions with an eigenvalue of less than 1/18 = 0.055 were omitted, and the first 10 dimensions were used for calculating the explained variances. Applying this approach, the percentage of explained variance of the first dimension was 83.8 and for the second dimension was 13.8. While this suggests a two-dimensional solution in which nearly all substantial information in the data was contained, the size of the eigenvalues may be inflated through the multiple imputation we applied. This, however, has no effect on the associations between the variables which are of prime interest here.

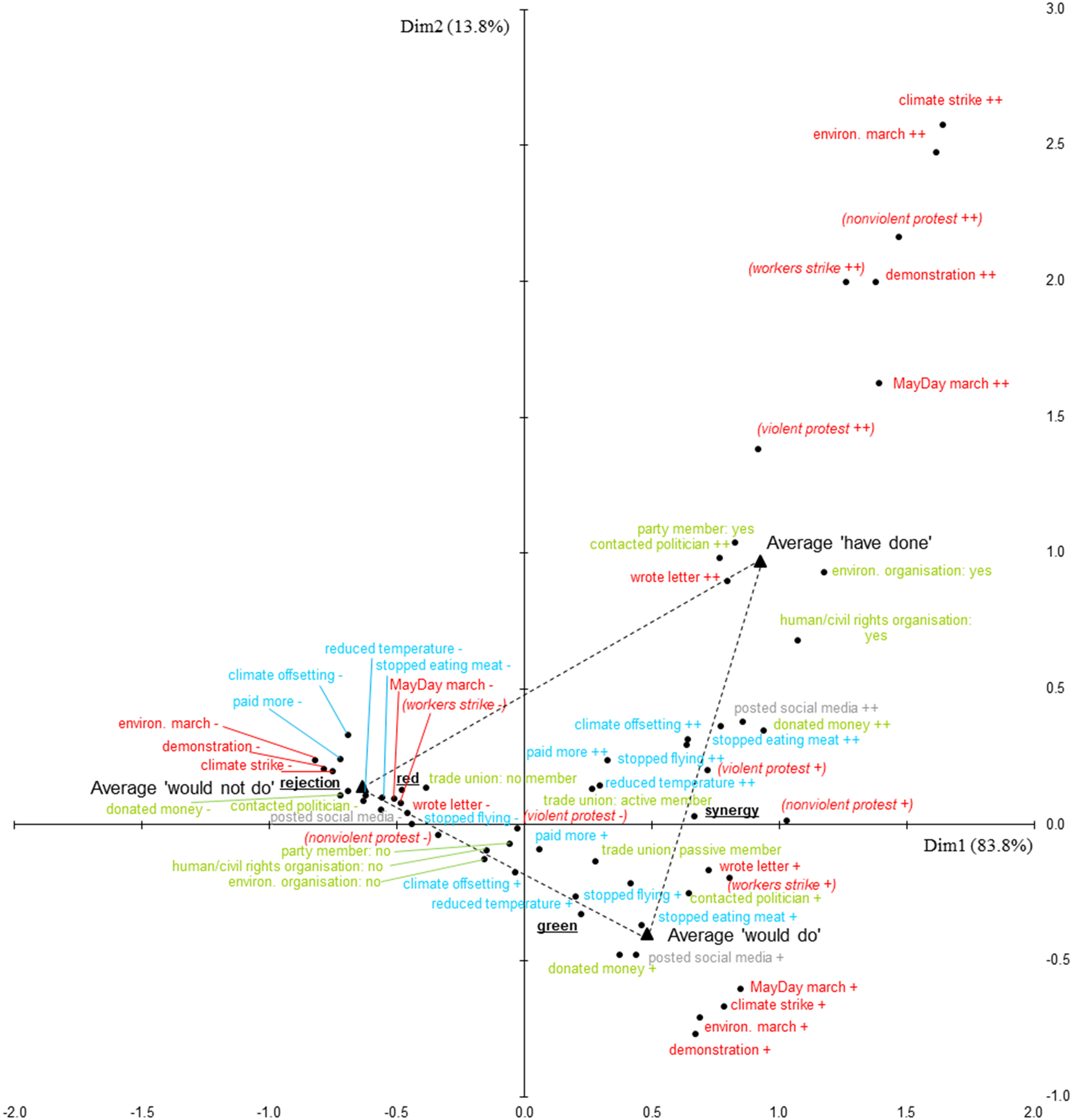

The relationships between all variables actively included in the MCA are visualized in Figure 1, which plots the positions of the variables’ categories on the first and the second dimension. The categories of the three supplementary political action variables are depicted in italics and surrounded by parentheses. They did not contribute to the calculation of the dimensions, but their coordinates were calculated afterwards.

Figure 1. Graph of the active categories, MCA (supplementary variables in brackets, n = 1529).

Description of dimensions and patterns of political action

The first dimension (horizontal axis) shows the difference between reluctance towards and support for political action. On the left side, we find the categories of those who ‘would not do’ (–) the different forms of political action all located close to each other. This reflects a response pattern expressed by persons who tend to be reluctant to most kinds of political actions. In contrast, the right-hand side shows support for political action through the categories of ‘would do’ (+) and ‘have done’ (++) the different types of political action. The categories furthest towards the right-hand side represent the strongest engagement in and willingness to take part in various forms of political action. Thus, persons who chose these categories and reported to have participated in demonstrations, environmental marches, or climate strikes as well as in a May Day demonstration are the politically most active. The second dimension (vertical axis) reflects the difference between a general willingness to take part in political action and the actual engagement in various forms of political action. So, in the upper area of the map, we find the categories of ‘have done’ (++), and in the lower area we find the categories of ‘would do’ (+).

To show the structure of political action items more clearly, we plotted points for the averages of all of the ‘have done’, ‘would do’, and ‘would not do’ answers and connected them with dotted lines to form a triangle of political action. It becomes apparent that actual engagement in non-institutionalized forms of political action (red categories, ++), particularly in terms of protesting, are most distant from the triangle and from the average of having engaged in political action. These distances are the result of the rather small amount of respondents actually engaging in this type of political action, which also can be seen as an indication that persons have to be strongly committed in order to take to the streets. An exception is writing a letter to the editor, which is close to the average of actual engagement. This is due to the fact that it requires less effort compared to protesting. The supplementary categories of having participated in violent or non-violent protests, as well as in a workers’ strike, appear in the same area of the map. This further underpins that non-institutional political action forms a distinct mode that requires greater personal commitment and is relatively disconnected from other types of action.

Actual engagement in institutionalized forms of political action (green categories, ++), e.g., in terms of organizational membership and contacting a politician/official, appears rather close to the average of the ‘have done’ categories. Being an active member of a trade union is close to the centre of the map, indicating that it has no distinctive characteristic. Considering the comparatively high degree of trade union membership in Sweden, this is less surprising. Also, donating money is a bit more common and less connected to the more demanding types of political action. Posting in social media as an example of digitally networked participation closely follows the pattern of donating money.

Certain types of lifestyle and consumerist politics (blue categories, ++) are spread around the centre of the map. This indicates that they are more common among respondents than other forms of political action (see also Table A in the supplementary material; cf. Dalton Reference Dalton2015). Having stopped flying or eating meat, as well as offsetting carbon emissions, are a bit more distant from the centre and are more strongly contributing to the first dimension while paying money for eco-efficient home devices and reducing thermostat settings are relatively often performed and do not contribute to either of the two dimensions. This is a not-too-surprising result because the former requires greater personal commitment than the latter.

The positions of the ‘would do’ categories cluster around the lower right corner of the triangle. Individuals who express a willingness to participate in institutionalized types of political action seem to be equally willing to participate in lifestyle and consumerist politics. Only the respondents expressing willingness to participate in non-institutional forms of political action deviate a bit because these categories are separated from the other categories and are close to each other within the lower right area of the map. Finally, the categories of ‘would not do’ are located to the left of the centre of the map. Their close positioning to each other indicates a high similarity between all of the ‘would not do’ answers irrespective of the type of political action. Thus, to be reluctant towards one type of political action generally seems to be associated with reluctance to any other type of political action.

Exploring relationships between eco-social attitudes and political action

When it comes to the four attitude types and their interconnections with political action, three main patterns emerge that follow the three nodes of the political action triangle. Firstly, the eco-social attitude type of synergy contributes to the first dimension to an above-average extent. This indicates that synergetic attitudes are most strongly related to higher political engagement because it has the highest positive value on dimension one and are closest to the average position of all the ‘have done’ answers. Respondents who expressed support consistent with an eco-social agenda are engaged in various kinds of political action – ranging from institutionalized forms to digitally networked participation, and above all, lifestyle politics. The synergy attitude type is also rather close to the average of the ‘would do’ political action categories, indicating that individuals with synergetic eco-social attitudes are also willing to, for instance, write a letter to an editor or to contact a politician or public official. To some extent, these patterns seem to correspond to the concept of ‘the engaged citizenship’ through more active and direct forms of political action (Dalton Reference Dalton2008). Being concerned about social and ecological issues involves taking a wider perspective on political problems and, as argued by Görtz and Dahl (Reference Görtz and Dahl2020), a broader conceptualization of politics more likely leads to a stronger motivation for political action. Thus, respondents expressing synergy attitudes might very likely be more politically active.

Secondly, the green crowding-out attitude type is contributing more to the second dimension than to the first dimension and is closest to the average of all the ‘would do’ categories and represents a willingness to take part in political action, mostly so in institutionalized forms of political action, digitally networked participation, and lifestyle politics, and less to non-institutionalized forms. Thus, respondents supporting a green but less so a social welfare agenda indicate a sympathy to engage in political action while not often actually getting involved in it. The reason might lie in the well-known gap between environmental attitudes and behaviour (e.g., Kollmuss and Agyeman Reference Kollmuss and Agyeman2002). Various personal and economic factors might function as barriers to environmentally friendly behaviour, particularly in the case of lifestyle actions that increase expenses, but also to participation in other types of political action that is otherwise facilitated by greater amounts of resources such as time and money (Dalton Reference Dalton2017). Another plausible explanation could be that the answers reflect social desirability or a logic of appropriateness, i.e., respondents might actually not be willing to act but know that this would socially be expected from them. It might also reflect that they do not believe their participation is needed at the moment.

Thirdly, red crowding-out and rejection attitudes are both located in the negative range of the first dimension, which means that these attitude types are connected to a reluctance towards all types of political action. Respondents with red crowding-out attitudes tend, for example, neither to be trade union members nor to attend May Day marches. This is a somewhat unexpected result due to the traditional understanding of welfare supporters as individuals with lower occupational status (Emilsson Reference Emilsson2022), e.g., blue-collar workers who traditionally are associated with May Day marches (Hylmö and Wennerhag Reference Hylmö, Wennerhag, Giugni and Grasso2015), and with trade union memberships (see Holmberg et al. Reference Holmberg, Näsman, Oscarsson, Pettersson and Tryggvason2023, who also note that membership in blue-collar unions has fallen during the last 30 years). In particular, the red crowding-out respondents tend to be reluctant towards various modes of lifestyle politics such as offsetting carbon emissions, or not eating meat. One plausible explanation is that they fear being burdened by the costs of environmental policies, which in turn make them non-supportive of environmental action. The position of respondents with rejection attitudes reflects a larger syndrome of political alienation where a lack of active citizenship goes hand in hand with rejecting any state or societal interventions in the private sphere and an unwillingness to take responsibility for society, including caring less about ecological conditions (see also Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Max Koch, Emilsson, Hildingsson and Khan2021).

The three clusters of political action and their socio-economic and political characteristics

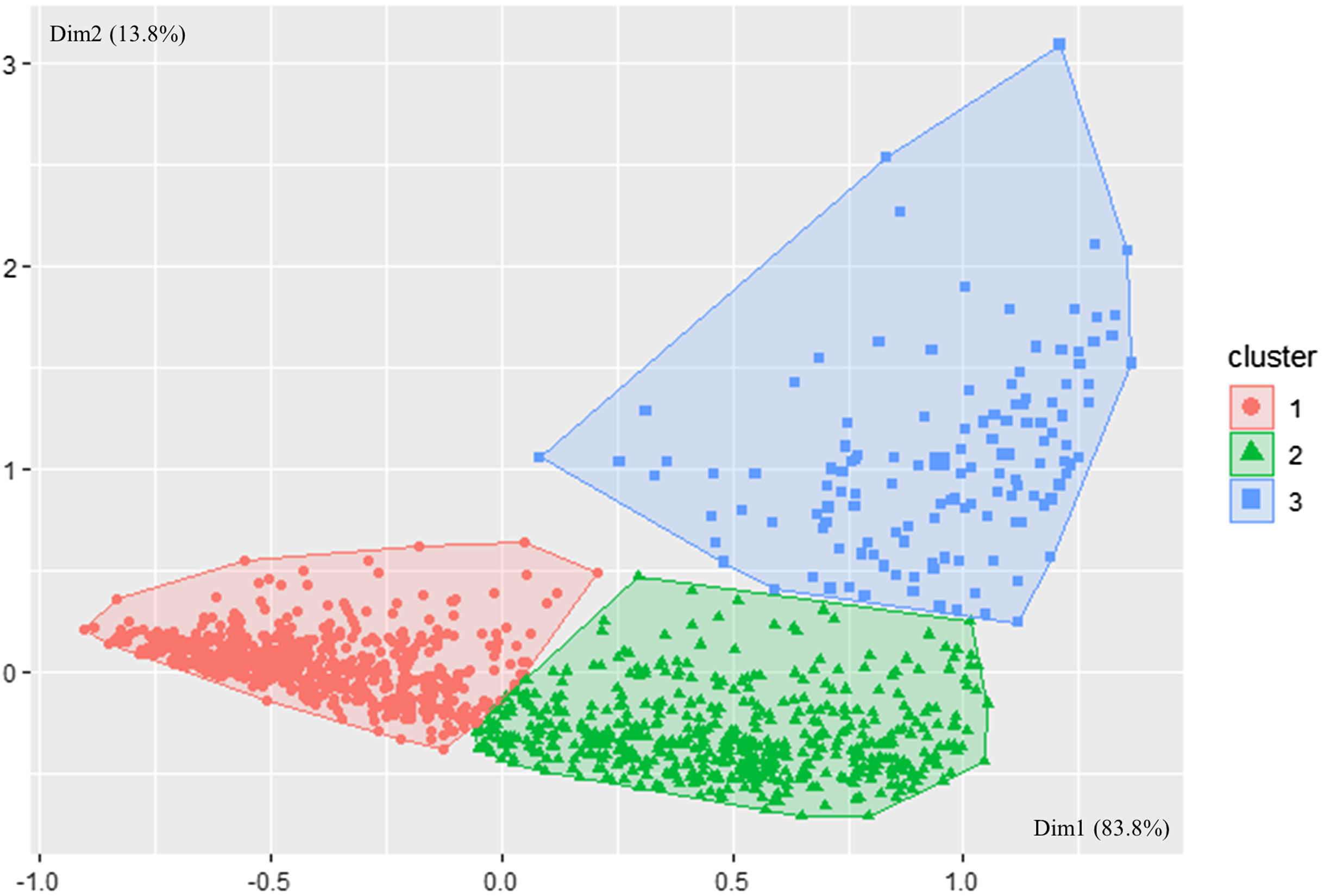

The agglomerative hierarchical clustering of respondents with regard to their scores on the first and second MCA dimensions led to a partitioning that reflects the three answer categories (have done, would do, would not do) and their average positions in the two-dimensional MCA space. Three clusters were identified that we label as the reluctant (cluster 1), the sympathetic (cluster 2) and the active (cluster 3). Figure 2 shows the positions of all respondents in the MCA space and their cluster affiliations.Footnote 2 In the following, we describe the three clusters with respect to the respondents’ socio-economic and political characteristics.

Figure 2. Cloud of individuals in the space of the MCA grouped in three clusters (cluster 1 = reluctant; cluster 2 = sympathetic; cluster 3 = active).

Cluster 1: The reluctant (n = 828; 54.2%)

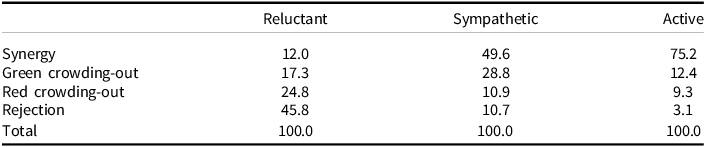

A large majority of respondents in the reluctant cluster, which contains more than half of the respondents, would not do any kind of institutionalized nor any non-institutionalized or digital political action. The reluctance of this large majority could be understood in relation to previous research indicating that only relatively small shares of individuals take part in more active and direct forms of political action (Klandermans Reference Klandermans, DA, della Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013; Saunders and Shlomo Reference Saunders and Shlomo2020). Most of the respondents in this cluster are particularly reluctant to lifestyle political action like stop eating meat and/or stop flying. They also show very low membership in organizations, including membership in trade unions. Nearly half of these respondents have the rejection attitude pattern, and another quarter has the red crowding-out attitude pattern (see Table 2). Being reluctant is more common among men (55%) than among women (45%). Respondents in this cluster also tend to be older, one-third is 65 years or older, and have the lowest educational attainment. Moreover, respondents in this cluster report the lowest levels of institutional trust. Nearly 60% place themselves to the right on the left-right scale and one-fifth would vote for the right-wing populist Sweden Democratic party. That we find the red crowding-out pattern in this context could be understood as a result of mainly older individuals having a traditional and conservative welfare state orientation, aiming for status quo, while seeing environmental policies as a burden. Along these lines, it has also been shown that Swedish blue-collar voters have been turning steadily to the Sweden Democrats during the last decade (Holmberg et al. Reference Holmberg, Näsman, Oscarsson, Pettersson and Tryggvason2023). A reason for this could be that the blue-collars – who have been shown to be susceptible to authoritarian views (Lipset Reference Lipset1959) – no longer feel represented by left parties as these have become too liberal for them and are now, in times of rising costs and migration problems, turning towards other parties which promise solidarity and security within close national borders. In terms of the individual-level characteristics in this reluctant cluster, our findings mirror previous research about political action, notably in terms of males, older generations and those with lower levels of education being less actively engaged (cf. Dalton Reference Dalton2017). It should also be mentioned that regarding the low levels of trade union membership, the old age of these respondents may play a crucial role, for example, retired respondents could have been trade union members when they were still part of the workforce.

Table 2. Eco-social attitudes of the three clusters (n=1471, in per cent)

The differences between the three clusters are highly significant (p < 0.001) with Cramer’s V = 0.4.

Cluster 2: The sympathetic (n = 572; 37.4%)

Compared to respondents in the previous cluster, sympathetic respondents more often take part in political action and, in particular, they most often choose the ‘would do’ categories. They also have a higher degree of organizational membership, but still lower compared to the third ‘active’ cluster. Regarding the attitudes of the sympathetic cluster, which makes up more than one-third of the respondents, half of them express a synergy attitude pattern, and nearly one-third express a green-crowding out attitude pattern (see Table 2). There tend to be slightly more women than men in this cluster, and also slightly more skilled workers and respondents belonging to the lower-grade service class. In terms of political orientation, around 60% place themselves to the left on the left-right scale and the Social Democratic party is the most preferred political party.

Cluster 3: The active (n = 129; 8.4%)

Respondents in the small cluster of the active are most often actually engaged in all modes of political action. They also have the highest organizational membership rates, i.e., membership in a political party, a human/civil rights organization or an environmental organization, which ranges from around 26 to 45%, and about two-thirds are trade union members. ‘Active’ respondents very often express a synergy attitude pattern, i.e., around 75% (see Table 2). Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, the results show that about two-thirds are women, and respondents in this cluster are also the youngest ones. They tend to have the lowest incomes, but also the highest educational attainment. Most of the respondents belong to the highest-grade service class, and there are few skilled workers. Finally, a very large share of the respondents in this cluster, i.e., around 80%, place themselves to the left on the left-right scale, and a substantial share sympathize with the Left party while also the Green party gains some support.

Overall, the results of the cluster analysis correspond well with previous research on political action but also help us to better understand the differences between the sympathetic and the active clusters. Respondents in the active cluster, compared to the sympathetic cluster, tend for example to be even more leftist, well-educated, and younger, i.e., the kind of individual-level characteristics that are associated with higher degrees of political action (e.g., Dalton Reference Dalton2017; Saunders and Shlomo Reference Saunders and Shlomo2020; Taniguchi and Marshall Reference Taniguchi and Marshall2018).

Conclusions

This study shows that there are interlinkages between eco-social attitudes and various modes of political action to prevent environmental change and promote social welfare. Following an exploratory approach to the study of attitudes and political action, by using MCA and cluster analysis, we were able to visualize and examine the relationships between eco-social attitudes and political action in the case of Sweden. This resulted in the emergence of a three-node pattern forming a political action triangle: synergetic attitudes are most strongly related to active political engagement and green crowding-out attitudes are most related to sympathy for and a general willingness to take part in political action, while red crowding-out and rejection attitudes are closely related to reluctance towards all types of political action.

While our point of the departure has been to overcome divides between separate social welfare and environmental agendas (cf. Fischer-Kowalski Reference Fischer-Kowalski and JD2015; Koch and Mont Reference Koch and Mont2016) by exploring the links between eco-social attitudes and political action, our results illuminate which groups of individuals are engaged in various modes of political action towards, but also which groups might be supportive of or reluctant to, social-ecological transformations. This is central to the ambition to better understand what it might take to get broader parts of the population to accept pathways towards sustainable welfare. Not only can the three-node pattern forming a political action triangle be understood in terms of divides in the population, but it becomes even more apparent when adding a layer of individual-level characteristics. The cluster analysis showed that socio-political factors such as education, age and, most importantly, the political left-right orientation are salient with respect to the three clusters.

The results of the cluster analysis indicate that one specific group of individuals could be pushing for social-ecological transformations, i.e., ‘the active’ ones who most often express synergetic attitudes in support of both environmental and social welfare concerns, and who are most strongly engaged in political action. Although the share of these respondents is quite small, it is nevertheless interesting to think in terms of social ‘tipping points’, which implies that ‘minority groups can initiate social change dynamics in the emergence of new social conventions’ (Centola et al. Reference Centola, Becker, Brackbill and Baronchelli2018). While the politically active cluster might be seen as some kind of eco-social avant-garde, potentially reflecting a critical mass for progressive action, such change dynamics are heavily reliant on the capacity to also attract support in broader constituencies. In this regard, individuals in the sympathetic cluster who reveal a willingness to act through various forms of political action are of particular interest. However, more needs to be known about what prevents them from actually taking part in political action. In particular, it would be valuable to better understand what it would take for those sympathizers holding synergetic attitudes to actually get actively engaged while exploring further the differences between the politically active with synergetic attitudes and the sympathetic ones with green crowding-out attitudes that might elucidate the importance of joint social and environmental concerns for motivating political action. While the value of social justice concerns for ecological citizenship has been theorized (e.g., Jagers Reference Jagers2009), such concerns have seldom been the focus of empirical investigation. Our results show that being both environmentally and socially concerned is associated with stronger political commitment and actual political action, a finding that deserves to be studied further. Future research could, for example, investigate whether certain ecological and social dispositions (growth orientation, views on nature, support for the welfare state, justice values, etc.) that underlie the eco-social attitude types are connected to specific political actions.

Moreover, the divides in the population are particularly evident between the most ‘leftist’ individuals who are often highly politically engaged and express synergetic attitudes, and individuals with a right-wing orientation who are more likely to be reluctant towards all types of political action. There are also some sociodemographic characteristics that distinguish the three clusters of political action from each other, as for example educational attainment, gender, and age. While the politically active with synergetic attitudes seem to have resources to engage in political action with respect to high educational attainment and higher social class positions, the reluctant ones with either rejection or red crowding-out attitude patterns are associated with factors less favourable to political action, e.g., lower levels of trust and lower levels of educational attainment. The red crowding-out pattern might be understood in relation to a ‘welfare nationalism’ relatively common among persons in precarious situations who conceive of the ecological discourse as elitist and lacking recognition of the regressive impacts of environmental policies. The rejection pattern indicates adherence to ‘minimal state’ intervention and a lack of active forms of citizenship (see the ‘passive anti-ecological conservativism’ and ‘fossil liberalism’ positions in Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Max Koch, Emilsson, Hildingsson and Khan2021).

Thus, getting everybody ‘on board’ the urgently needed endeavour of social-ecological transformations seems unlikely. Instead, it will be a demanding and complex task to forge alliances and find majorities in support of an eco-social policy agenda, not only against the resistance of groups that are interested in avoiding such a change but also considering that large parts of the population are less prepared to actively engage in various modes of political action.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773924000213.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their very insightful and constructive comments, which improved the article significantly.

Funding statement

This work was supported by FORMAS, the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development, under Grant number 2016-00340.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.