INTRODUCTION

On Saturday evening, 21 June 1851, near Cockeysville, Maryland, an enslaved man named Ralph Thompson, “aged about 33 years, a bright mulatto, about 5 feet 10 inches in height”, decided to take matters into his own hands and claim his liberty, fleeing his legal owner Samuel Moore. One month later, on Monday 21 July, after Thompson “was seen entering Baltimore on Thursday or Friday afternoon last”, Moore placed an advertisement in the local newspaper, The Baltimore Sun. “He has an impediment in his speech”, and was “wearing blue pantaloons and a white felt ha[t]”. Moore described him in a few words and offered the rather low reward of $3 “for his recovery and return”.Footnote 1 Though sparse, this information is sufficient to conclude that Ralph Thompson was a runaway slave who sought refuge within an urban setting. Some historians have used the term “urban maroon” to categorize people like him – but how appropriate is the term maroon?

Latin Americanists feature most prominently among those who have described slave flight to urban areas as a form of “urban marronage”. Historians have labelled runaway slaves hiding in cities cimarrones urbanos (urban maroons), and cities like Havana and Buenos Aires an immense palenque urbano (urban maroon settlement).Footnote 2 In Francophone settings, runaway slaves in cities are likewise claimed to be performing marronnage urbain.Footnote 3 North Americanists and Anglophone scholars have also increasingly applied the term marronage, including in very recent publications.Footnote 4 Simultaneously, there are a number of works that focus on runaway slaves in urban settings, yet do not use the terms maroons and marronage.Footnote 5

Noting these different approaches in scholarship, it is worthwhile taking a close look at the concept of marronage. While this discussion of its definition no doubt contains a great deal of controversy, it should be clear that while all marronage entails the dimension of escape from slavery, not all escapes from slavery should be seen as marronage. So, what are the features that turn some escapees from slavery into maroons and others not? To contribute to a more nuanced understanding, this article examines individual escapees from slavery, the communities they joined, and the broader slaveholding society to emphasize that the interplay and mutual relations of all three should be taken into consideration.

Historian Steven Hahn has carried out a similar examination, discussing whether some African American communities in the US northern states during the antebellum period (c.1800–1860) showed features of a maroon society. While, ultimately, he does not come to an explicit conclusion, he recognizes the value of the concept because it reveals insights into the political consciousness of enslaved and free African Americans.Footnote 6 This article agrees with Hahn, in that marronage is a concept that promises a great many insights into the lives of people of whom we have few first-hand accounts in the historical archives. In cases of very limited self-documentation, we must shift the analysis to group behaviour to draw conclusions about identity and modes of thinking. The concept of marronage can deliver many such insights, but we should have a conversation about how to use it.

Given that publications on slave flight are numerous, and that they increasingly include urban areas as destinations as well, a city will also be the locale of this analysis. Baltimore presents an ideal case for establishing whether runaway slaves and their receiving societies were maroons because, in the antebellum period, it hosted a substantial and growing free black population and continuously attracted runaway slaves. This article will therefore discuss the applicability of the concept of marronage to runaway slaves and their receiving society in the urban context of Baltimore. The first section analyses the historiography of marronage in the Americas. The second introduces the historical context of the city of Baltimore and documents the presence of runaway slaves in the city. The third and fourth sections respectively discuss the arguments that speak in favour of and against marronage in Baltimore. Ultimately, this article dismisses the suitability of the concept of marronage for describing slave flight to Baltimore. However, this examination will reveal the core of the concept. This concerns, above all, the aspect of resistance. In this context, it will be argued that resistance in the sense of rejecting the control of the dominant society should be included in the general definition of marronage.

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL CHALLENGES

The idea of urban maroons derives from the concept of “conventional” maroons. Historical literature usually defines them as legally enslaved men and women in the Americas who escaped slavery by fleeing to remote wilderness areas and securing their freedom. They either formed a settlement with others or joined an existing community. The best-known maroon communities of the Americas were to be found in Jamaica, Brazil, and Suriname, because they posed a threat to colonial authority and, consequently, left a variety of archival traces. This holds particularly true for maroon communities that engaged in warfare or other violent confrontations with the authorities.Footnote 7 Besides, there were also maroons whose existence was less known, but who also enjoyed autonomy and organized themselves separately from dominant white society. For example, Sylviane Diouf explores several US-American maroons in her book Slavery's Exiles. These were slaves who escaped their bonded condition, inhabited wilderness areas on the peripheries or in the general vicinity of plantations and formed groups of different sizes.Footnote 8 These people tried to avoid open confrontation with authorities at all costs.

A number of Latin and North American revisionists have lately started to challenge the emphasis on physical isolation and independence from slaveholding society. These scholars recognize that many maroons did in fact remain in contact with white society (including their fellow bondspeople).Footnote 9 Diouf and Ted Maris-Wolf have shown, in the US-American context, that the grade of isolation experienced by wilderness maroons was not as high as has been hitherto assumed. Especially in the nineteenth century, some wilderness maroons moved into closer contact with the dominant society and were even employed by white people.Footnote 10 For Brazil, historians already claimed in the 1990s that there had always been interaction and even cooperation between maroons and slaveholding society.Footnote 11

In order to keep the concept broad, João José Reis and Flávio dos Santos Gomes have suggested that marronage is “flight that led to the formation of groups of fugitive slaves with whom other social persons frequently associated, [and which] took place in the Americas where slavery flourished”.Footnote 12 This definition shifts the focus away from geographical demarcation and pays tribute to the variety among the numerous maroon communities. It does not account for warfare, recognition of autonomy, or cultural aspects. Rather, Reis and Santos Gomes emphasize flight, community, and the continual arrival of newcomers. This approach is helpful because it makes the concept of marronage applicable to different contexts throughout the Americas. However, it runs the risk of inflating the concept by simply equating marronage with slave flight.

These broader definitions have an important linguistic dimension. In Hispanic and Francophone contexts, all runaway slaves are usually called cimarrones or marrons (maroons), respectively. The use of these terms is often based on archival material. In Spanish, for example, the equivalents of runaway slave depots (where runaways were jailed) were depósitos de cimarrones, with the word “maroon” used as a substitute for runaway slave.Footnote 13 In Anglophone settings, however, the application of the concept is not justified by historical sources. Within the United States, Louisiana presents a special case where jail ledgers, up until the mid-nineteenth century, were kept partly in French and in which the terms “runaway slave” and “marron” were used interchangeably.Footnote 14 The issue is that historians often do not sufficiently explain their use of the terms they find in archival sources. Transfers from primary sources as well as translations of scholarship into English often lack a sufficient level of reflection.Footnote 15

This linguistic aspect also has another historiographical consequence. Until this day, many historians refer to petit and grand marronage to mark the distinction between runaway slaves who absconded for a short period of time and those who did so on a long-term or permanent basis.Footnote 16 Although this terminology is likewise rooted in historical documents, namely the writings of the French colonial authorities of the nineteenth century,Footnote 17 its adoption is deeply problematic because it connects a duration to the impact of the action. The implications are manifold. It obscures the original intentions of the people fleeing, shifts the focus away from what happened after they absconded, and ranks the outcome of slave flight as resistance.Footnote 18

Coming back to the urban context, Dennis Cowles has noted the difficulty of including urban runaways into the category of marronage but mistakenly implied that the reason was that urban fugitives did not escape slavery definitively.Footnote 19 His assumption is understandable since historians have only recently begun to engage in depth with long-term and permanent slave flight to urban areas.Footnote 20 Earlier contributions usually approached runaway slaves in cities, located within slaveholding territory, as temporary absconders because it is difficult to find explicit evidence about the length of their presence in the cities.Footnote 21 The argument here is not that urban maroons did not exist, nor that maroons never went to the cities,Footnote 22 but rather that we need to thoroughly reflect on what marronage means before we can apply it to the urban context – or not.

These reflections lead us to Leslie Manigat's widely cited definition of marronage. She has claimed that the aspiration of a maroon was “to live, actually free, but as an outlaw, in areas (generally in the woods or in the mountains) where he [or she] could escape the control of the colonial power and the plantocratic establishment”.Footnote 23 The aspects of being outlaws and escaping the control of the authorities have often been disregarded in other, broader, definitions, but this is precisely where the strength of the concept lies. Hence this article will take these two points as deserving of closer attention.

The following parts will scan runaway slaves in Baltimore through the lens of marronage, thereby applying Manigat's definition of outlawing and avoidance of control, and the revisionists’ call not to focus on geographical location and territorial integrity. It is particularly important to keep in mind that looking at the individuals fleeing does not suffice. Standing alone, slave flight does not tell us enough about the escapee's relation with slaveholding society.Footnote 24 Because marronage has a dimension of identity within the broader community, we must include those who absorb the runaways into the analysis.Footnote 25 The next part, however, will first provide evidence of the presence of runaway slaves in Baltimore.

RUNAWAY SLAVES IN BALTIMORE

Ralph Thompson, the enslaved man named in the opening paragraph, escaped slavery by running away, joining an existing free black community in Baltimore, and trying to live as de facto free within slaveholding territory. Thompson is not an isolated case. Already during the eighteenth century, but much more markedly during the nineteenth century, runaway slaves gravitated to the growing cities of the southern states in increasing numbers. As is well known, enslaved people also fled to the northern states and places outside the US, where slavery was abolished and freedom could be obtained in official ways.Footnote 26 But their endeavours in southern cities are especially remarkable, because, by staying within the slaveholding South, the freedom these escapees could obtain was of an illegal nature. It had no basis in law but nevertheless allowed them to live as if they were free – just like conventional maroons who went “underground”.Footnote 27

Jail statistics and newspaper announcements show that in the early 1830s, the Baltimore City Jail locked up one suspected runaway slave on average every one and a half days. Over the entire course of the antebellum era, newspapers were full of advertisements for runaway slaves believed to be hiding in the city.Footnote 28 Due to its expansion and rapid growth, this article estimates that Baltimore received dozens of them annually in the early nineteenth century and hundreds in the decades before the Civil War. The new and confusing environment of burgeoning cities added to the chances of successful concealment. And for the whole South, historian Richard Wade has claimed that “[t]hose living in illegality in the city must have been several times as numerous as those who were discovered”.Footnote 29 Although the numbers remained small in comparison to the overall numbers of black residents, and even more so to the total population, the runaway community and their offspring must have amounted to thousands of undocumented city dwellers over the course of the period under analysis.

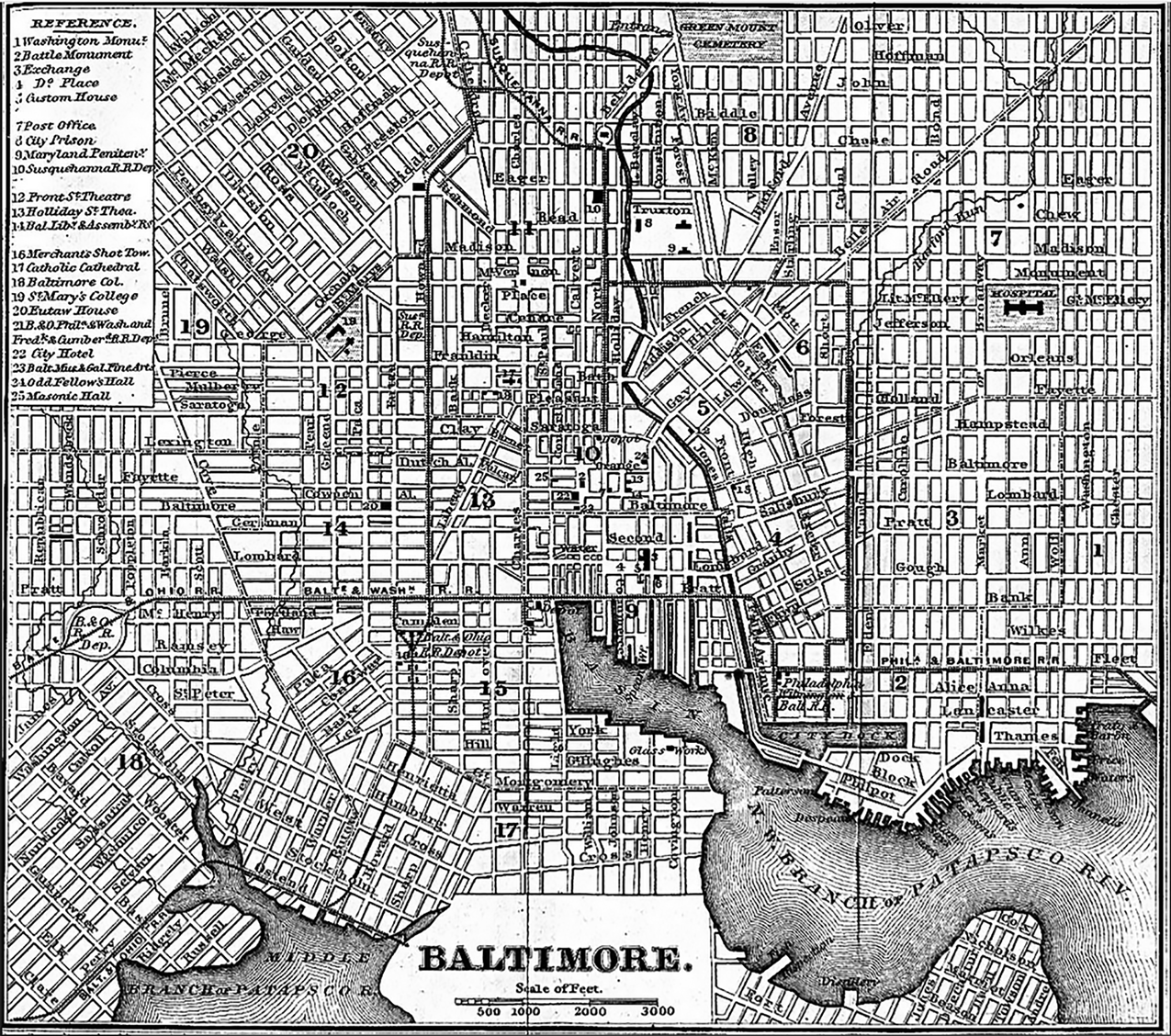

Baltimore was a thriving commercial city situated on the northern border of the southern states (see Figure 1). It grew to be the second largest American city until around 1850 and became the fourth largest by 1860. Among its 212,000 inhabitants, 25,700 were free men, women, and children of African descent. This part of the population had grown extensively from 2,700 in 1800 (see Table 1). Part of the growth was the result of immigration of refugees from Saint-Domingue following the Haitian Revolution.Footnote 30 The number of free black people in the state of Maryland increased from 8,000 in 1790 to 84,000 by 1860. At that time, a similar growth and the relative predominance of free black people were to be found only in Latin America and the Caribbean.Footnote 31 By the mid-century, these people were almost exclusively born in the state.Footnote 32 The rapid growth in numbers of free African Americans in Maryland was a legacy of the ideological changes of the revolutionary era, which produced more liberal manumission laws in the Upper South than in the Lower South.Footnote 33 Giving in to the pressures of their slaves, it led hundreds of slaveholders to free their bondspeople, up until approximately 1810, and spurred the autonomous growth of the free black population in the years afterwards.Footnote 34 These were the same developments that led to formal abolitions in the US northern states and throughout the Americas.

Figure 1. Map of the eastern part of the United States, circa 1860.

Table 1. Free African American, enslaved, and total population of Baltimore.

Sources: US Bureau of the Census, Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in The United States: 1790 to 1990, available at: https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/1998/demo/POP-twps0027.html; last accessed 8 January 2019; US Bureau of the Census, Aggregate Number of Persons within the United States in the Year 1810 (Washington, DC, 1811); DeBow, Seventh Census; US 8th Census, 1860, Population of the United States.

Baltimore's location is important, as enslaved African Americans heading to the city from the surrounding counties or further south could also have chosen the free soil of the North where slavery had been abolished.Footnote 35 Ralph Thompson, for instance, escaped from Cockeysville. From there, the distance to the Pennsylvanian border was almost the same as to Baltimore. A number of reasons, though, encouraged Thompson and others like him to make the choices they made. Employment prospects for black men were better in the southern than in the northern states (in fact, they became better the farther south one went, as demonstrated by Leonard CurryFootnote 36), families and friends provided an incentive to stay, and the lack of networks in the North acted as a discouragement.

For example, nineteen-year-old runaway James Harris, with a “very large mouth [and] thick African lips”, as his owner described him in an advertisement, could have used his private and work-related network to conceal himself in Fell's Point, a waterfront area in Baltimore. He had lived there prior to his sale and his new owner therefore believed him to be “lurking about that part of the city” in 1842.Footnote 37 Moreover, the information on the timespan of flight that some slaveholders included in the announcements clearly indicates that it was not only temporary absconders who gravitated to Baltimore. To give two examples out of many, a slaveowner knew in 1832 that his bondsman Ben Anderson had “been secreting himself about this city [Baltimore] for three months, passing as a free man” but he was unable to find him.Footnote 38 In 1853, Henry Kemp had already been gone for five months, when his Baltimore master advertised that “[h]e is an excellent waiter, and is supposed to be at some large Hotel acting in that capacity”.Footnote 39

Historian T. Stephen Whitman has noticed that, from the slaveholders’ point of view, the threat of losing a runaway slave to the growing ranks of Baltimore's free black population became more pronounced over time. Maryland slaveowners therefore systematically employed delayed manumissions as a strategy to keep their slaves under control. The idea was that bondspeople, who saw the prospect of becoming legally free in the future, would more willingly surrender to their fate in the present. Control and the impetus to high performance were, hence, important incentives for manumission. In Baltimore, many slaveholders who manumitted slaves out of this logic bought others in the aftermath. This is why the number of manumissions in Maryland was relatively high. Between 1790 and 1860, 45,000 enslaved people gained their freedom by manumission.Footnote 40 These dynamics led to the highest absolute numbers of free black persons of all the American states and dramatically changed the social worlds of black and white Marylanders. Hundreds of runaways joined the free black population and contributed to its growth.

Despite the higher odds of being legally set free, enslaved men, women, and children from Maryland and other regions in the Upper South were the most severely affected by sale and forced migration. In the nineteenth century, a massive domestic slave trade trafficked bondspeople to the southern and western territories of the expanding republic. Between 1790 and 1860, approximately one million enslaved people were moved from the Upper to the Lower South. An additional two million were displaced within the same states.Footnote 41 As historians have calculated, between 1830 and 1860, approximately 18,500 enslaved men, women, and children were sold out of Maryland. In Baltimore, every third first marriage was broken up, ten to fifteen per cent of enslaved young adults were sold out of state, and one in three children under fifteen years old were separated from at least one parent.Footnote 42

Separating families and uprooting them through forced migrations, the internal slave trade of the nineteenth century was a factor that both aggravated the lives of enslaved people and triggered escapes. Slaveholders were eager to excuse this common practice, which contradicted their claims of being benevolent masters, by blaming the slaves for their own sales. Recounting the story of a free black man in Baltimore whose family was about to be sold to New Orleans, The Baltimore Sun wrote in 1850 that “these slaves would have been permitted to have remained here undisturbed for years if all sense of security had not been destroyed by the temptation held out to run away. Every man who owns this kind of property now thinks of hurrying it off further south”.Footnote 43 With this opinion, the editor claimed it was the slaves’ own fault if they were sold – and he expressed how much of an issue slave flight was.

According to Whitman, many more owners suspected that runaways remained in the city after 1790. During the 1810s, fugitive slaves were thought to be in that city three to four times more often than in other places. If taking locations close to the city into consideration as well, the share grows even more.Footnote 44 Runaway slaves to Baltimore did not usually migrate long distances. As jail records reveal, most were from counties in proximity to the city. Some came from the city itself or from northern Virginia counties. A small number of runaways were caught attempting to return home after being sold further south in the direction of the internal slave trade.Footnote 45 Additionally, some runaways to Baltimore viewed Baltimore as a transit zone, from which to migrate to the free states, even though, as historian Barbara Fields has noted, it was a better place of refuge than a departure point for other safe harbours.Footnote 46

Like other southern cities, Baltimore received two types of runaways: urban (from Baltimore or other cities and towns) and rural. In addition to the challenges all escaped slaves faced, rural runaways had to adapt to an urban economy and become urban workers. Slaves who had experienced greater mobility, for example by having worked as (self-)hired slaves, or who had lived apart from their masters, had clear advantages. Many were used to an autonomous life and the requirements of work in the city. The same mobility described by Jared Hardesty and Marion Pluskota in this issue for eighteenth-century Boston and for the French Caribbean, respectively, also allowed urban bondspeople in the nineteenth-century US South to leave their owners. This was increasingly the case for enslaved people in the southern cities, where the self-hire system came to be an integral part of urban slavery. It holds true even for Baltimore, where slavery had never been strong (see Table 1).Footnote 47

To be sure, those who dared to flee enslavement were determined and courageous persons who risked a lot to set themselves free. Runaways who went to Baltimore escaped for very similar reasons as those who became maroons in the classic sense: fear of sale; separation from loved ones; mistreatment; overwork; or the simple conviction that they no longer wanted to be slaves.Footnote 48 As already stated, to determine whether they can be understood as maroons, we must expand the view to include the community they chose to join. As the next two sections will show, arguments exist both for and against applying the concept of marronage to Baltimore's black population.

RESEMBLANCES OF BLACK BALTIMOREANS TO A MAROON COMMUNITY

Before turning to the points that repudiate the concept of marronage for Baltimore, this section engages with aspects that might lead us to consider black Baltimoreans as maroons in the first place. These include the recruitment of newcomers, solidarity among black people, legal attacks by slaveholding society, and criminalization.Footnote 49

Family networks were an important reason for the significant increase in slave flight to Baltimore in the nineteenth century – despite abolition in the North. People who fled slavery were motivated to stay close to their loved ones. Because manumitted slaves often moved to Baltimore, an increasing number of bondspeople had free family members in the city. In general, their personal networks were broad. Calvin Schermerhorn has laid out that many enslaved families were rooted in this region of the country for several generations. The Chesapeake Bay, home to the city of Baltimore on its north-western shores, had been one of the pilot projects of African American slavery. Two hundred years after the first enslaved Africans put their feet on soil that would later become the United States, family networks were firm and extended over rural and urban areas. In later times, Schermerhorn stresses, as enslaved families were increasingly broken up and a significant number of slaves experienced greater mobility and more varied employment, these kin networks expanded geographically.Footnote 50

It was not only the desire of enslaved people to break free and join their loved ones in Baltimore, the latter also had an incentive in actively supporting slave flight. Through this constant reception of newcomers, the free black community responded to a topic that was a common feature of maroon societies.Footnote 51 Free black people had always been suspected of aiding runaways, but the harbouring of relatives and acquaintances must have worked increasingly well over time. As the nineteenth century progressed, a growing number of enslaved people had friends and relatives who lived in Baltimore, as evidenced by runaway slave advertisements in newspapers. Whereas in the late eighteenth century, a few of these mentioned the family relations of the runaways,Footnote 52 masters later increasingly gave information about the relatives of the absconder and also, in numerous cases, about presumed employment.

Charles A. Pye, the legal owner of the twenty-year-old, “rather handsome”, Watt, who left him around 1 March 1816, announced a reward of $100. “He has some relations at Mr. Foxall's, in Georgetown, and a free brother in Baltimore, where he will probably endeavour to reach. It is likely he will have a pass, as some of his relations read and write”, Pye claimed.Footnote 53 Likewise, enslaved Ellick, eighteen years old, who called himself Alexander Brown, absconded from Jefferson County, (now West) Virginia. His mother lived near Baltimore and his sister in the city. Therefore, his owner believed that he had gone there in 1840.Footnote 54 These and other comparable sources reveal important information about the personal networks of African Americans. As early as the 1830s, free black inhabitants outnumbered the city's enslaved residents by over 10,000, meaning they had more possibilities to shelter and aid runaways.Footnote 55 (For an impression of the size of Baltimore, see Figure 2) These practical aspects combined with the broad social networks increased the willingness to aid runaways from slavery.

Figure 2. Map of Baltimore, Maryland, 1848.

Also outside of family structures, black people of different legal statuses showed a remarkable solidarity with each other. For instance, newspapers frequently published advertisements by free black residents claiming to have lost their freedom papers.Footnote 56 Many must have passed them on to slaves who, in turn, could use them to travel to Baltimore and to pass themselves off as free people. Others forged passes for runaways, harboured them, or provided them with contacts to find work. Autobiographer John Thompson, for instance, gave the example of an enslaved man writing passes for other slaves.Footnote 57 Runaway Tom was believed to use the papers of the dead James Lucas to pass himself off as the deceased.Footnote 58 The African American community must not be viewed only as a passive receiving society, but also as an active recruiter of enslaved sisters, husbands, friends, and co-workers.

This loyalty in the black community originated in their shared lived realities but was also affected by material conditions and influenced by broader society.Footnote 59 Solidarity was especially strong in Baltimore, compared to other American places. One of the reasons for this was that, in the Upper South, upward social mobility was almost unachievable for any person of visible African descent, which led to the strengthening of horizontal solidarities and a degree of “racial unity”.Footnote 60 This unity extended over slavery and freedom because both free and enslaved African Americans came to be treated very much alike. Slavery was not only a labour relation and a legal status, it was also a racial order that affected people who stood outside of this institution.

Part of this racial control was that black Baltimoreans were criminalized for actions that did not qualify as offences for white people. For example, black people who did not work in the service of white economic interests could be apprehended and forced to work and their children could be bound out as apprentices.Footnote 61 Since 1831, any free black person who moved into Maryland or returned from a trip outside the state could legally be enslaved. Furthermore, free black Marylanders could be sold into slavery for crimes for which whites were punished significantly less harshly.Footnote 62 This befell Thomas Phelps in 1838, “a mulatto” who “was arraigned for stealing sundry bead bags and a quantity of ribbons and lace” of a value of fifteen dollars. “He was found guilty, and, this being his second offence, he was sentenced to be sold out of the State.”Footnote 63 Conventional maroons also faced the constant danger of (re-)enslavement.Footnote 64 This threat of enslavement for free African Americans moved them closer to those already (or still) enslaved. And this proximity was further reinforced by legislation that aimed to define the status and the behaviour of all black people. From 1832 onwards, Baltimore's free blacks started to receive the same punishments for offences as legally enslaved people. The focus on race, rather than legal status, further blurred the distinction between free and enslaved.Footnote 65

Paired with a process of criminalization went a process of systematic illegalization. If black Baltimoreans purchased firearms, liquor, or dogs without a licence, they were criminalized. The same applied to almost everything sold by African Americans without a written permit. When they did it nonetheless, it was seen as illegal. Other institutions, such as black schools and benevolent societies, had to operate clandestinely and were frequently shut down. Significantly, after 1831, black people were prohibited from assembling and were required to follow a 10 o'clock curfew.Footnote 66 Since black people still had to survive, they were driven into semi-clandestine or illegal economic and social activities, which meant being driven underground.

Baltimore's free black population also became partly illegalized in itself; this corresponded to the outlawing of maroons.Footnote 67 Although not all maroons lived in illegality, most moved outside the reach of the law and jurisdiction.Footnote 68 The illegalization occurred on various levels. Already in 1805, Maryland's General Assembly warned that “great mischiefs have arisen from slaves coming into possession of certificates of free Negroes, by running away and passing as free under the faith of such certificates”. Consequently, free black Marylanders were asked to prove their freedom and to acquire corresponding documentation.Footnote 69 From 1824 onwards, manumitted slaves were required to pay a one-dollar fee to receive a certificate of freedom from the clerk of the court.Footnote 70 Those who could not afford the dollar, had a problem and could not prove their freedom without major efforts. In 1832, another law was enacted requiring slaves manumitted from that year onwards to leave Maryland. This was a response to the violently suppressed Nat Turner rebellion of 1831 in Virginia, which heightened white fears of black people. Legislators knew that the law would not work, because it was a copy of a similar, Virginia law of 1806, which ordered manumitted slaves out of the state within twelve months of becoming free.Footnote 71 It was nevertheless enacted, first as a desperate move to convince free African Americans to migrate to Liberia (which eventually proved unsuccessful), and second, because it had the side effect of creating a large population of undocumented people who were stripped of any legal grounds to become politically active. Although there is no evidence of an organized round-up of illegal residents, as happened in Richmond, Virginia,Footnote 72 the law of 1832 attached an illegal status to hundreds of newly freed black people who were not willing to abandon their families and homes.Footnote 73

Like illegalized free black Baltimoreans, runaway slaves depended on anonymity and invisibility before the authorities. This was the nature of the illegal freedom that they could achieve in regions where slavery officially existed. And in Baltimore, they joined a population that faced criminalization and illegalization itself. This does, admittedly, bring the experiences of the city's black community very close to those of maroons, whose freedom was most of the time insecure and fragile. However, there are more factors of marronage to consider. Thus far, it has been shown that Baltimore's black community was discriminated against and excluded. The next section will argue that this exclusion did not stem from the desire of black Baltimoreans and that they, quite contrarily, aspired to inclusion in the dominant society. Hence they were not maroons.

ARGUMENTS AGAINST SEEING BLACK BALTIMOREANS AS A MAROON COMMUNITY

Slaveholding society usually sees marronage as a threat to the social order.Footnote 74 The measures taken against this threat are often visible in legislative sources. In Maryland, by contrast, the legislative framework developed over time in a way that made it less difficult for runaway slaves to pass as free people, and for their helpers at least not more difficult to shelter or employ them. In the early nineteenth century, in Maryland, as in most other states of the American South, people of African descent were generally supposed to be slaves.Footnote 75 This was problematic when they were taken up as alleged runaway slaves. If they could not prove their freedom, they ran the risk of being sold into slavery. From 1817 onwards, however – although discriminating greatly against the free black population (see the previous section) – legislative adjustments made it easier for runaways to succeed in their endeavours – within the state of Maryland, nota bene.Footnote 76

As legal documents show, in 1817, due to the large numbers of free black inhabitants, the state of Maryland relieved black people of the burden of proof to verify their legal freedom and instead assumed all of them to be free unless proven otherwise.Footnote 77 If a black person jailed as a suspected runaway in Maryland was believed to be free, she or he was to be released and the expenses were levied on the county. In 1824, the General Assembly complained “that Baltimore county is subjected to great annual expense on account of negroes being committed to the jail of that county, on suspicion of being runaway slaves”.Footnote 78 The act, however, remained unchanged until the Civil War. In 1831, a new law prohibited the hire, employment, or harbouring of illegal free black immigrants to the state, but no mention was made of runaway slaves from Maryland. And although a reward of $6 for persons apprehending runaway slaves was made mandatory in 1806, and increased to $30 in 1832, by 1860 the reward was retracted if the runaways did not remove themselves to a sufficient distance: “[N]o reward shall be paid under this section for taking up any slave in the county in which said slave is hired, or in which his owner resides”.Footnote 79

Additionally, from 1860 on, the commitment of an assumed runaway slave to jail was to be only announced in the Baltimore city papers. Earlier, it was also to be made public in the surrounding areas and in Washington, DC.Footnote 80 Slave flight from Baltimore City or County did not entail a mandatory bounty that would have encouraged uninvolved persons to be on the lookout for the absconder. This is remarkable, especially because it seemed that by the early 1850s, a growing number of runaways taken up in Baltimore were from the city itself.Footnote 81 In 1849, slaveholders from Maryland's Eastern Shore publicly reproached their bondspeople for fleeing in large numbers: “If something is not done, and that speedily too, there will be but few slaves remaining on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in a few years. They are running off almost daily”, lamented a local master.Footnote 82 Sixty slaves allegedly absconded in 1856 alone, and another rash of escapes took place in 1858.Footnote 83 In this context, the calculations by John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger are important, as they do not account for an increase in flight to the northern states.Footnote 84 Thus, a large share of fleeing enslaved people must have found themselves in Baltimore. These developments, which spread over the course of the antebellum era, stood in contrast to the common attitudes of legislators towards maroons, who usually tried to implement harsher codes to hamper slave flight.Footnote 85 Legislative relaxation is an indication that legislators did not see runaway slaves within Maryland as a particular threat to the social order.

This observation is also important when it comes to the receiving society in Baltimore. Slavery had many facets and implications, but it was primarily an institution to make some people work for the benefit of other people. In the United States, many white people held the belief that black people were there to serve them.Footnote 86 However, slavery in Baltimore and other cities dramatically decreased. By 1860, the census counted 2,200 enslaved Baltimoreans, who constituted a mere one per cent of the city's total population.Footnote 87 Most slaveholders in the city owned but a single slave.Footnote 88 Quaker Joseph Gurney, who visited Baltimore in the late 1830s, claimed that “the influence of the system [of slavery] on society in general is much limited by the small proportion of slaves”.Footnote 89 Yet, institutionalized slavery had another “influence on society” in that it cast a shadow on those who were affected by the same racial order as slaves. Slavery was much more powerful than Gurney assumed.

Early in the century, the abolition of slavery was openly discussed in the Maryland press, in religious congregations, and even by the General Assembly – but the state never brought itself to formally end it. Despite the subordinate position of slavery in Maryland, however, the new constitution of Maryland of 1851, finally, included a prohibition of abolition.Footnote 90 The reasons were not of an economic nature, although slavery was still widespread in rural Maryland, especially in wheat agriculture.Footnote 91 The argument for the prohibition of abolition is, rather, that the racialized system kept people of African descent in their assigned places.

The fact that the social order white society envisioned was also working well without holding large numbers of black people in legal slavery can be retraced with the statements of anti-black institutions, which changed in tone over time. For example, in 1817, the Maryland Colonization Society voiced that free black people had a clear “vicious and mischievous” potential and strongly advocated their removal from the entire country.Footnote 92 Around the same time, the widely read Niles’ Weekly Register warned that “free blacks among us are less honest and correct, less industrious and not so much to be depended upon” than slaves.Footnote 93 Free black people in Maryland were seen explicitly as a problem, including being a danger. By the later antebellum period, however, the voices were no longer that strong, and some came to opposite opinions. In 1858, the governor of Maryland, Thomas H. Hicks, made it clear that where black people “can find employment, chiefly as domestics and laborers, as in her populous city [Baltimore], and in the more thickly settled portions of the State, […] there is but little of the evil of their vagrancy and idleness felt, not much complaint of its existence”.Footnote 94

A year later, the Convention of Maryland Slaveholders likewise showed no interest in removing free African Americans from the state: “[T]he committee came to the conclusion”, it reported, “that it was highly inexpedient to undertake any measure for the general removal of our free black population from the State. […] Their removal from the State would deduct nearly 50 per cent from the household and agricultural labor furnished by people of this color […]”. Instead of enslaving the entire free black population or expelling them from the country, it would be better to “make these people orderly, industrious and productive”, the slaveholders agreed.Footnote 95

Whereas contradictory opinions of white people regarding free black people had always existed, the ones in favour of expelling them were markedly less unanimous in the later years of the antebellum period.Footnote 96 The labour aspect, as mentioned by Hicks and the Maryland slaveholders, was very important. Compliance with their own labour exploitation and the subordination free black people displayed were precisely what white society expected from them. Black men and women undertook the most menial work requiring the least skills. Over time, their already precarious socio-economic situation noticeably worsened, and poverty aggravated racial discrimination.Footnote 97 Baltimore was the southern city where black people owned the least property. In 1850, free black inhabitants who owned property constituted a mere 0.06 per cent of the city's inhabitants.Footnote 98 Remarkably, this was still too much for some white Marylanders. In 1860, the spokesman of the Baltimore convention asked to legally bar black people from purchasing houses or leasing them for more than a year.Footnote 99 Due to racist legislation, free black people had very few resources to resist. Although they were considered persons by law, not property like slaves, their societal, political, and economic opportunities were dramatically limited. In most states, persons of colour were not allowed to vote, to testify in court, or to sit on juries. They were not allowed to freely travel or assemble, nor could they marry whites. Legislative restrictions emphasized political and judicial exclusion.Footnote 100

Steven Hahn has also taken the dimension of exclusion into account. His considerations are of special interest in this last section on points that further reject the application of the concept of marronage to Baltimore. Hahn has examined black communities in the US northern states along demographics, migration patterns, residency, and social and political organization. He points to their internal coherence, social experiences, autonomous institutions, and legal background as factors that might qualify them for marronage.Footnote 101 Hahn's view corresponds to the revisionists’ call for a reassessment of the physical isolation of maroons. They agree that it is more fruitful to put weight on their social outsider status instead of territorial integrity.Footnote 102 The issue is that while Hahn expressly stresses societal exclusion and autonomous organization as a prominent feature of marronage, he fails to see that this exclusion emanated from white society alone.Footnote 103

African Americans organized themselves independently of white society, through ideology, religion, schools, benevolent societies, and social spaces. In fact, Baltimore's black community established their own religious institutions quite early on. Although severely restricted in many aspects of their lives, free black Baltimoreans had their own official places of worship since the early nineteenth century. The African Methodist Bethel Society was founded in 1815, and by 1860 there were sixteen black churches and missions in Baltimore with at least 6,400 registered members who worshipped in their own fashion. This relative autonomy allowed preachers the liberty to interpret the Bible in a way that did more justice to black people's experiences. Moreover, through churches, black communities in different places interacted with each other. The African Methodist Episcopal Church of Baltimore, established in 1816, was connected to those in Philadelphia, Charleston, and New Orleans.Footnote 104

This social exclusion and independent organization, however, did not stem from a desire for demarcation from white society. Rather, it was the second-best choice black people had after being rejected. There is a considerable amount of literature dedicated to the fight of African Americans to be recognized as equal elements of American society.Footnote 105 Hahn has rightly observed that exclusion created spaces to construct new black politics,Footnote 106 yet the fight for citizenship ultimately always dominated black struggle.Footnote 107 Moreover, historian Martha Jones has recently shown for Baltimore that independent black organizations also followed the rules of white society. The very incorporation of the church, the symbolic and literal centre of most black communities, occurred according to official law. Land had to be formally purchased, the church officially registered, an enslaved minister perhaps manumitted. In this process, they became involved with white attorneys, justices of the peace, and clerks.Footnote 108 It is not that black Baltimoreans did not fight to change the system, but they did it from within.

All these are points where Baltimore's free black community palpably diverges from the concept of a maroon society. While many maroon communities had economic ties to slaveholding society as well, they did not integrate as thoroughly into the economic place assigned to them by white society as the majority of black people in Baltimore did. Although they lived in severe poverty, they did not elude the legal reach of society, which drastically discriminated against them. On the one hand, it was a clear improvement for escapees from slavery as they were not under the control of a master. On the other, the loss of individual control gave way to the collective control of the whole African American population. Whereas, as Frederick Law Olmsted, a journalist from the US North, wrote in 1860 that in the countryside, “the security of the whites” depended “upon the constant, habitual, and instinctive surveillance and authority of all white people over all black”,Footnote 109 in the urban context, the authorities took on the matter of social control.Footnote 110 Apparently, control by society at large and the restrictions of severe, discriminatory laws was something African Americans could collectively handle, especially in the anonymity of a city.

The compliance with their own subordination was exactly what black activist David Walker criticized in his Appeal to the Coloured Citizens in 1829.Footnote 111 As historian Stephen Kantrowitz has claimed, rather than challenging the political system and the nation itself, Walker demanded a place in it.Footnote 112 Maroons, by contrast, would not strive for citizenship in a slaveholding republic. They would not vote and not subordinate themselves to the rules and laws of the very people that upheld the slavery they or their co-maroons had escaped from. Sylviane Diouf has neatly summarized that maroons were distinct from runaways in that the latter “refused enslavement but not the larger society, which they wanted to be part of even if they knew it could only be at its periphery”. Instead of rejecting its hegemony, they “continued to live under the discriminatory laws of white society, still subservient and controlled”.Footnote 113 Persons who fled slavery sought physical liberation from bondage and forced labour. For them, freedom meant acknowledgement and acceptance, and the power to decide freely about their private and public lives.Footnote 114 Joining or establishing a maroon community would have provided these privileges. These people, however, abandoned the hopes of being fully accepted into American society.

CONCLUSION

This article has discussed a number of aspects that speak in favour of and against understanding runaway slaves in Baltimore as maroons and their receiving society as a maroon community. Based on some of the findings, African Americans in Baltimore could well have been a maroon community. They were de facto free people surrounded by slavery, and the community existed at the (not physical) margins of white society. The reception of runaways, a freedom in danger, criminalization of their activities, and illegalization of (parts of) its members were realities conventional maroons also experienced. What contradicts marronage is the view of them by white society and the collective attitude of Baltimore's black population towards their own condition. Those in power came to see them not as a threat, and black Baltimoreans condoned the forms of control and surveillance white society imposed on them. Most important was their desire to be included in the larger society. Because these counterarguments are integral features of the concept of marronage and cannot be disregarded, this article concludes that marronage is not an adequate concept to understand their experiences.

Applying this concept to runaway slaves in Baltimore, however, has provided some insights. By following the footsteps of people fleeing slavery and seeking refuge in the city, it has become apparent that the nature of resistance changed in this process. Individuals absconding from their – legally righteous – enslaved condition were rebels in the truest meaning of the word. Yet, by integrating into Baltimore's black community, runaway slaves turned into assimilated residents who attempted to elevate their status by following the very rules that kept the members of this community at the lowest social and economic levels.Footnote 115 This course is different from the resistance displayed by maroons. In this light, this article hopes to contribute to the way historians use the term marronage. Far from claiming that urban maroons did not exist, it has argued that running away alone is not a sufficient indication to qualify for marronage; we always have to consider the community as a whole. Particularly, the dimension of resistance should also be an (perhaps the most) important measurement to be included in the concept. Maroons made conscious choices to reject the control and hegemony of the larger society over their lives. This element should be part of the generic definition of marronage.