Movement One: Scientart

Information Arts Circuit

For close to 40 years, Claudia Bucher’s art of “extended sentience” has created myriad experiential habitats for her performing body, while challenging audience members to join her imaginary leaps.Footnote 1 From enacting a mate-seeking beetle-cyborg (Coleoptera-Cyborg, 1986) to inventing an artificial trans-organism (Kinocognophore, 2003); from personifying an outer-space lichen colony daydreaming migratory signals (Lichen Femosa, 2017) to meditating midair as “an anemochore kite” on its right to not be wind-borne (To the Air Born?, 2019), Bucher demonstrates empathic kinships with other beings and nonbeings by fabricating formally elegant performance structures as alternative ecosystems. Bucher’s art practice exemplifies what Dick Higgins termed the “intermedial approach” (1966), thriving in the nexus of body art, endurance art, sculpture, installations, technologic and ecological art, mysticism, and science fiction. Bucher posits the role of an artist as, in her own summation, “an inventor, thinker, philosopher, activist, vision quester”; or, as she puts it, a “scientartist” (in Cheng Reference Cheng2006:18). Her work has contributed to the creative genre identified by Stephen Wilson as “information arts,” where art, science, and technology converge (2002:3). Taking “information” as organized data obtained through current transdisciplinary inquiry into how science, technology, and art intersect, Wilson’s coinage illuminates the techno-scientific research basis on which Bucher constructs her mythopoetic realms.

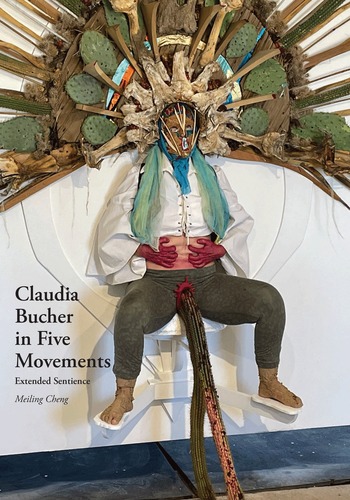

Figure 1. Claudia Bucher performing in F.L.U. Season. Mojavetia, Yucca Valley, California, 2022. (Photo by Meiling Cheng)

I have followed Bucher’s work since 2003, marveling at the trajectory of her oeuvre. Instead of a discernible pattern of chronological development, Bucher’s scientart presents a consistent stylistic template in support of both her recurrent themes and her sporadic shifts to divergent concerns. Central to Bucher’s style is her joining of performance with installation, using her virtuosic sculpting and engineering skills to fabricate intricate performance environments for her temporary habitation. Bucher often adds narrative scenarios to her durational actions, stimulating our visual, aural, haptic, kinesthetic, and cognitive senses in such an immersive way that they merge time and space, the performer and the performing site, into a phenomenological continuum. From this continuum, Bucher expresses what physicist Hermann Minkowski theorized as the coextensive “space-time” (see Mann Reference Mann2021; Einstein and Minkowski Reference Einstein and Minkowski1920), within which her body-in-performance survives, dreams, intones, evolves, and interacts with others.

Bucher’s spacetime performance-installations are imbued with a fluidity that is the result of combining disparate qualities: dynamism and dormancy, tactility and visuality, the actual and the virtual, the natural and the artificial, the scientific and the mystical, the solitary and the interactive. This convergent methodology has facilitated Bucher’s scientartistic pursuits to represent extended sentience. “Sentience” denotes sensory awareness, the capacity for feelings and sensations (Broom Reference Broom2019). As Bucher states, her concept was inspired by J. Scott Turner’s thesis of the “extended organism,” which he used to postulate “the physiology of animal-built structures” (2000:1). Turner argues that these structures are not “external to the animals that build them” but rather “parts of the animals themselves” (2). Echoing Turner’s liberally construed “physiology,” Bucher finds sentience among all beings—human or otherwise, living or nonliving. If her performances feature her sentient human self, then her installations exhibit the sentience of her extended self, the empathic physiology of her artist-built structures.

Bucher began using the term “extended sentience” to define her artistic practice as early as 2001 (Bucher Reference Bucher2022e), having replaced one word from Turner’s “extended organism” with a broader concept that may include synthetic and other nonorganic entities. This concept-phrase became culturally current when Kathrine Johansson (Reference Johansson2012) used it to analyze Canadian architect Philip Beesley’s 2010 Hylozoic Ground, an immersive kinetic sculpture “made of lightweight digitally fabricated components fitted with meshed microprocessors and sensors” (in VernissageTV 2010). In a short video documentary, Beesley likened the Hylozoic Ground environment to “a living system,” in which “embedded machine intelligence allows human interaction to trigger breathing, caressing, and swallowing motions and hybrid metabolic exchanges” (VernissageTV 2010). Johansson focused her assessment on Beesley’s staging of “empathy” as “something physical, functional and symbolically transcendental” (2012:270). She noted that empathy was an expression of human “consciousness” as “motion,” detectable in “micro-scale communication” (270). She further describes “motion” as “what we usually understand as ‘feeling’ and ‘sentience’” (270). Johansson largely equated “empathy” with “sentience,” which she regarded ecologically “as a subtle communication that affects the sculpture [Hylozoic Ground] internally and gives it communicational contact with external environments mainly through a complexity of responsive functions” (2012:272). In Johansson’s analysis, then, extended sentience is the performative effect of Hylozoic Ground’s interactions with human viewers, thereby changing its configurations and simulating signs of life.

Sentience as empathy certainly evokes my emotional response to Bucher’s performative installations. Different from Beesley’s reliance on “motion” as an interactive affect, however, Bucher’s proposition of “extended sentience” offers a dramatic lens to guide her critics/audiences in perceiving even the static structures supporting the human performer as alive, aware, and equivalent in their sentient status to that of the viewers’ own organic physiologies. Emulating architecturally gifted animals such as the otters and bees honored in Turner’s book on animal-built structures, Bucher creates complex performance machines, which operate like fabricated ecosystems-cum-artificial organisms, at once metaphorical and functional, introspective and dialogic. Bucher’s performance machines—after Turner’s “extended organism”—are performative superorganisms; her performance sites are perceptual extensions of her artist’s body. By implication, the inanimate devices that have constituted and adorned her performing ecosystems become her body’s sentient prostheses.

Bucher’s scientart recalls the pioneering information artist Stelarc’s theory of the human body’s dependence on technological prostheses to enhance its capabilities for survival and communication with others. Stelarc’s notorious all-cap declaration—“THE BODY IS OBSOLETE”—reveals his optimistic embrace of technological progress in modifying the human body as “an object for designing” and a (weaker) partner in the human-machine interface (see Stelarc 2023). In contrast to Stelarc’s technophilia, Bucher’s information art grew out of her interest in performance art, which is a live art genre that prioritizes an artist’s embodied experience of a performance event. Thus, instead of showcasing technology per se, Bucher values herself performing in her techno-scientific pieces. Moreover, she has cultivated her “handywoman” skills to build physical—rather than solely coded or simulated—installation forms, often incorporating in one go the ancient poetics of corporeal empathy, the preindustrial manipulation of matter, and the bourgeoning technology of bioengineering.Footnote 2 Unlike her high-tech and institutionally sponsored fellow information artists such as Stelarc, or Eduardo Kac, who specializes in transgenic bio-art, Bucher’s scientart features a DIY sensibility. In lieu of science lab–subsidized virtual technology like Stelarc or gene-splicing biotechnology like Kac, Bucher uses a kind of analog expertise, including narratives, verbal coinage, carpentry, metallurgy, and other low-tech literary, theatrical, and artisanal techniques to produce her scientart.

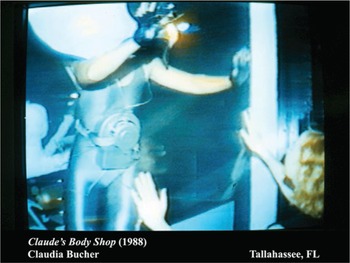

Figure 2. Claudia Bucher in Claude’s Body Shop. Performance view; still from video. Window on Gaines, Tallahassee, Florida, 1988. (Video by Stephen Bradley; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Bucher launched her transdisciplinary career in 1986, as a Florida State University civil engineering student and a young punk founder of Ca Laboratories International, an alternative arts/music space in Tallahassee, Florida. Then, in 1987, she was one of seven original members of Critical Art Ensemble (CAE)—but soon realized she preferred to create art individually rather than collectively.Footnote 3

Emblematic of the relatively low-tech scientart from her Tallahassee period is the performative installation piece Claude’s Body Shop (1988), a solo exhibition that took place in Window on Gaines, an alternative gallery space incorporating two storefront windows and adjacent streets.Footnote 4 Inspired by nearby business venues (including a body building club, a comic book store, and car repairs and parts shops), Bucher developed a futuristic scenario featuring typical sci-fi motifs of alien lifeforms, transorganic hybridity, interspecies exploitation and commercialism, and perpetual existence through prosthetic replacement and body augmentation. Red-lettered signage for Claude’s Body Shop hung above the Window, while a flyer advertised the shopping event to spectators and passersby: “Claude’s Body Shop. 50-percent off all items. We offer the largest selection of mutant body parts ever. It’s the deal of a lifetime” (see Nable Reference Nable1989:60). Displayed inside one store window was Bucher as “Claude’s Miracle Mutant”: the mutant’s head was a motorcycle fairing with headlights; on its torso was a bodysuit adorned with tubes, sensors, and electric wires; strapped to its mid-section was a battery-run front lantern and rear exhaust pipes; its legs were bound together with a pair of hubcaps on the outside of each leg. Inside another window was an array of spare and enhancement parts, each with a price tag. Out on the sidewalk Claude, the actor hired by Bucher to play the owner/barker, peddled the deluxe mutant prostheses amidst a high-intensity percussive soundtrack. Most viewers were more engaged with the barking Claude than the mutant, who was pacing, pausing, and staring at them from inside the window.

Perhaps the most significant critical impact on Claude’s Body Shop came from an unexpected source. On the third night of the performance, after the audience left, two cops stopped Claude from “selling” the “female on display” and threatened to arrest him for “soliciting for prostitution” (Nable Reference Nable1989:60). The cops—both female-presenting—read the performance as a front for the seedy commodification of female sexuality by a male pimp; their tacitly feminist reaction gendered the mutant as female. This inadvertent “audience” response betrays conventional values overlayed on an emergent phenomenon: a voiceless object with a homo-morphic torso adorned by numerous car parts must be a female, being sold against her will. As Bucher recalled, she intended for the deluxe cyborg character to be “hermaphroditic, but apparently I didn’t make my figure look androgynous enough”:

I find this frustrating because I am constantly thinking beyond gender and beyond humanity. I am always thinking about the organism and embodied existence across a wide spectrum, from the microscopic to the cosmological, to the networked, to the technologically engineered, to the memed and so on. (2005)

Bucher’s frustration reveals a challenge common to information artists: how to give their audience access to the contexts of their transdisciplinary pursuits. As Wilson notes, “Science, technology, and their associated cultural contexts are prime candidates for theory-based analysis because they create the mediated sign systems and contexts that shape the contemporary world” (2002:27). Thus, one way to provide access to an audience is to make theory and writing part of information art production. Wilson’s suggestion to converge theory, writing, and art—or science, technology, and art—reflects his aspiration to “update the notion of the arts as a zone of integration, questioning, and rebellion, in order to serve as an independent center of technological innovation and development” (28). I agree with Wilson’s integrative vision, but I believe artists are not solely responsible for explaining their information artworks to a live audience—think of Joseph Beuys’s How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965). Instead, information artists, like performance artists in the elusive vein of conceptual art, would benefit from—if not depend on—an expanding discursive circle that would include many variations of audience response, from the artists’ own confessionals, interviews, and statements, to their critics’ analytical deliberations, to the viewers’ eyewitness accounts and mediated testimonies, to even the interdiction issued by indignant cops.

In the spirit of joining this discursive circle, I offer my attempt to elucidate the conceptual/theoretical contexts of Bucher’s scientart. Following the artist’s lead, I relate her key concept, “extended sentience,” to her three other recurrent tropes: her preference for inventing portmanteaus to entitle her pieces; her frequent adoption of mythological characters, conceptual personas, theatrical alter egos, and spectral doubles in performances; and her habitual practice of endurance performances.

Movement Two: Portmanteaus

Wonderous Disorder

A linguistic manifestation of Bucher’s scientartistic convergence technology is the portmanteaus with which she entitles many of her performances. Derived from the neologism for a versatile piece of French furniture, a portmanteau blends two or more words into a new word to express a combined meaning of its parts. “Scientart” is, of course, a portmanteau. Like the playful and erudite Lewis Carroll with his “frumious” army of “slithy” and “frabjous” portmanteaus (see Dictionary.com 2020), Bucher thrives in spawning fantastic characters and scenarios and portraying them with incipient concept-words, her own imaginary and imaginative—shall we say, imaginarrative—signifiers. These imaginarrative titles appear conceptually sentient, emerging as poetic creatures made of compressed semantic units and alphabetical sounds, while functioning, in retrospect, as eponymous mementos for the vanished live artworks. Although Bucher didn’t entitle all her pieces with portmanteaus, tracing those she did maps out a significant part of her performance terrain. In fact, Bucher’s imaginarratives are too plentiful to survey in full: five samples here will suffice.

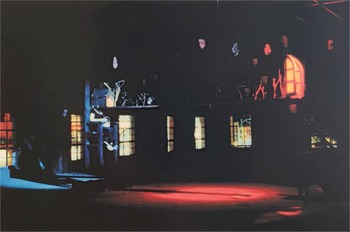

Figure 3. Claudia Bucher in CinderWhite Onomatopoeia. Performance installation view. NewTown at One Colorado, Pasadena, California, 1998. (Photo by Michelle Coe; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Coleoptera-Cyborg (1986) was her first professional performance in her earliest series of works that “explored the subject of biotechnology, genetic engineering, robotic prosthetic body extensions and reproduction” (Bucher Reference Bucher2008). The piece showcased a performing duo with black body paint, electric cords, and illuminated tubal extensions engaging in a mating ritual in a diorama. The accompanying zoographic narrative identified the two creatures as “a pair of mating transgenic cyborgs who were part black beetles” and part cyborgs; hence the hyphenated title “Coleoptera,” a taxonomic classification order for the beetles, and “Cyborgs,” famously defined by Donna Haraway in “A Cyborg Manifesto” as “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” (Haraway [Reference Haraway1985] 1991).

Fully fused portmanteaus soon entered Bucher’s conceptual universe. CinderWhite Onomatopoeia (1998) blended Cinderella and Snow White, referencing those fairytales’ sonorous motifs. Bucher recalls conceptualizing the piece as “an act of reclamation. I wanted to fuse [these fairytale] personas and embody the resultant persona within my own empowered revisionist narrative. The Onomatopoeia of the title refers to the act of giving these personas a new voice” (Bucher Reference Bucher2022a). Bucher as the young woman, CinderWhite, sits on a throne-like chair made of charred wood, suspended in midair, with her head hidden inside a fairytale doll house, “like a treasure box.” A wooden board dotted with miniature leafless tree branches, hung with cables and a hinged segment that goes around her neck and latches to a section attached to the suspended chair frame, stretches 14 feet forward, at the end of which are a pair of illuminated life-size bay windows (Bucher Reference Bucher2022a). Viewers can only see the performer’s face through the doll house’s front porch. Influenced by performance artist Laurie Anderson’s famous cyborg move of inserting a light bulb into her mouth (United States, 1983), Bucher further obscures her face with a magnifying glass that enlarges and distorts her mouth. CinderWhite, guided solely by touch, peels apples in a basket on her lap. Bucher had hung singed pages torn from fairytale books all over the installation. The burned pages reflecting stage lights look like stars in a galaxy, available to guide CinderWhite toward escape, possibly through the illuminated bay windows. Yet escape and freedom seem beyond reach for the suspended, confined figure. Bucher’s CinderWhite tells the story of young women “trying to manifest themselves yet getting stalled by negative forces” (Bucher Reference Bucher2022a), symbolized in fairytales by the misogynistically maligned evil stepmother.

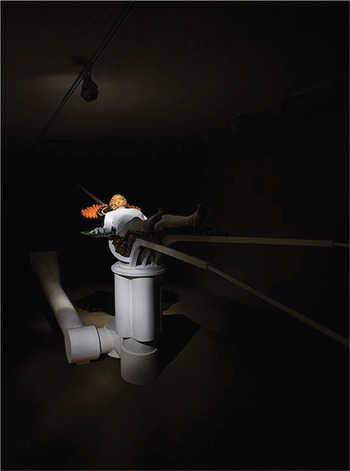

Figure 4. Claudia Bucher in Lichen Femosa. The 29 Palms Art Gallery, Twentynine Palms, California, 2017. Performance installation view. (Photo by John Van Vliet; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Omalogue of the Clauddha (2011) combined two elements from Bucher’s scientart: portmanteau and conceptual persona. The first title word fuses three words: om (a sacred chanting sound in yoga), Oma (grandmother in German and Dutch), and logue from travelogue. Clauddha introduced a conceptual persona with whom Bucher identified for a few years. Blending Claudia and Buddha, Clauddha is “a floating vessel-entity, trickster travel guide, meditating Time Lord, and prognosticating oracle” (Bucher Reference Bucher2022d). In Clauddha’s Omalogue, the trickster explorer rides in a sculptural vessel like a floating boat, featuring a cast of Bucher’s head and chest as the sail. The sculpture recalls Bucher’s mutant body of car parts in Claude’s Body Shop; its floating vessel, fusing a body cast of the artist’s upper torso with the boat, pays homage to the painterly imagery of the Spanish surrealist Remedios Varo, a perennial inspiration for Bucher.

Terrmotilla (2015) was a multiform piece, including an installation exhibition and an artist book. The title portmanteau—Terre (earth) + motile (capable of movement) + illa (feminine diminutive in Spanish) + the Ocotillo plant—captured the surrealist sci-fi motifs in the book of performative photographs dramatized by narrative captions. With a mixed tone of humor and literalism typical of a comic book, the collection of photos portrayed Terrmotilla, per the subtitle, as Spacetime Applied Research Systems. Bucher’s research infused Terrmotilla with documentation of the spacetime travel of certain “intraterrestrial organisms,” navigating with their “Joystick and divining rod,” “Gravitomagnetic sand calculator and quantum time keeping device” in a “transparent” spacetime vessel, passing through “micro wormholes” to map the rarely discerned “Observatron fold field” (Bucher Reference Bucher2015).

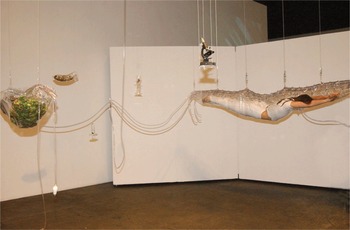

In her endurance performance Lichen Femosa: Song of Myself as Lichen on the International Space Station (2017), Bucher embodied a melded flora-fauna transpecies creature. Inspired by lichen, a complex lifeform evolving from the symbiotic merging of algae, bacteria, and fungi, with an adaptability for colonizing wide-ranging natural surfaces, Bucher created her performance persona, Lichen Femosa—fem for female and osa for a plural feminine suffix for osis, used in biochemistry/medicine (Bucher Reference Bucher2022b; see also MoOM 2018). As Lichen Femosa, Bucher lay on top of a structure imitating the robotic arm, Canadarm, of the International Space Station. She wore headgear with multicolored beads coating her whole face and head, evocative of lichen-covered rocks and tree trunks. In the darkened room of the 29 Palms Art Gallery in Twentynine Palms, California, Bucher appeared to be floating in a vast outer space. Intermittently, the performer hummed “a song language” to communicate with other lichens, luring them for interstellar migration.

What can we make of all these intricate linguistic games in Bucher’s scientart?

Figure 5. Claudia Bucher in Lichen Femosa. Performance installation view. The 29 Palms Art Gallery, Twentynine Palms, California, 2017. (Photo by John Van Vliet; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Bucher offers a clue in “Systems Poetics of a Physiological Imaginary as Applied to Kinocognophore,” her MFA thesis—allegedly a theoretical treatise written by Yvonne Zeeb (one of Bucher’s performance alter egos)—submitted to the Pasadena Art Center. Citing from Paul Virilio’s prediction that biology was becoming teratology (the study of monsters; see Virilio and Lotringer Reference Virilio and Lotringer2002:117), Zeeb writes, “The monstrous, which derives from the Latin, monstrum, ‘divine portent of misfortune,’ signifies disorder. Organisms that are aesthetically and functionally handicapped represent collapsed negentropic engineering or a wonderous disorder” (2005:3). Monstrous in their cryptic spelling and eccentric semantics, Bucher’s portmanteau titles function in equal measure as blueprints, indexes, and discursive relics of her scientart. Having absorbed teratological creativity from their author, they become wondrously vibrant, defying the normal cognitive order for humans: oblivion.

Movement Three: Not Not Me

Personas, Alter Egos, Doubles

As a performative effect, extended sentience is perhaps easiest to perceive when the performing entity in question is live and human. We do not need to suspend our disbelief or stretch our empathy to recognize the vitality of a fellow human being engaged in performance for our spectatorial gaze. Bucher’s adoption of personas—those figurative entities serving as the artist’s surrogates—underscores this perception.

In “Systems Poetics” (2005), Yvonne Zeeb, as the author and investigator, cited a journal entry, dated August 2002, from the scientartist Bucher, who reflected on her use of personae in performances:

I think up until now my work has been more about the “persona” and its conceptual attributes rather than the body as phenomenon itself. Reading Deleuze and Guattari in class has been helpful in this regard. Their idea of Conceptual Personae and Aesthetic Figures is apt. For several years before I entered the program, my performative strategy was to use my person to embody/enact conceptual paradigms through a persona or conflation of several personae. In this way my work was functioning with a bias towards the theatrical rather than the sculptural. (in Zeeb Reference Zeeb2005:53)

In What Is Philosophy? Deleuze and Guattari highlight the reciprocity between philosophers and their conceptual personae through a naming practice: “Conceptual personae are the philosopher’s ‘heteronyms,’ and the philosopher’s name is the simple pseudonym of his personae” (1994:64). I take this passage as the authors explaining the enabling power of an impersonal voice: the conceptual persona permits the philosopher to speak in a tongue that both reveals and exceeds their own voice—in much the same way that a dramatic character might enable an actor to speak more fully for both. Deleuze and Guattari further nominate an analogous figure in literature: “The difference between conceptual personae and aesthetic figures consists first of all in this: the former are the powers of concepts, and the latter are the powers of affects and percepts” (1994:65). Bucher the scientartist noted her understanding: “The Conceptual Persona embodies the philosophers’ ideas and is a way to make ideas manifest. […] An example of this would be Nietzsche’s Zarathustra. […] The corollary to this tool in the realm of art is the Aesthetic Figure, a character such as Don Juan. However, there can be blurring and slippage between these two categories […]” (in Zeeb Reference Zeeb2005:53).

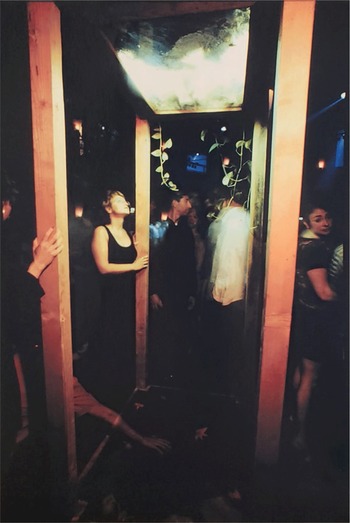

Figure 6. Claudia Bucher in Persephone Is Echo Is Narcissus (1997). Performance installation view with audience. XX The Happening, curated by Deborah Oliver for LACE 20th anniversary. Hollywood Athletic Club, Los Angeles, CA, 1998. (Photo courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Bucher recognizes the blurred boundary between the conceptual persona and aesthetic figure. This recognition, in turn, qualifies her earlier distinction between her “theatrical” and “sculptural” uses of “persona” as equally slippery. A better distinction lies in how she sourced her performance personae: prior to her Ecosystems series in 2003, she often assumed personas that were partially readymade. CinderWhite, for instance, conflated two preexisting fairytale personae through whom Bucher critiqued the patriarchal power structure that had stifled many women. In contrast, her later performances mostly involved self-invented conceptual personae/aesthetic figures. All her personae are, to varying degrees, both theatrical and sculptural.

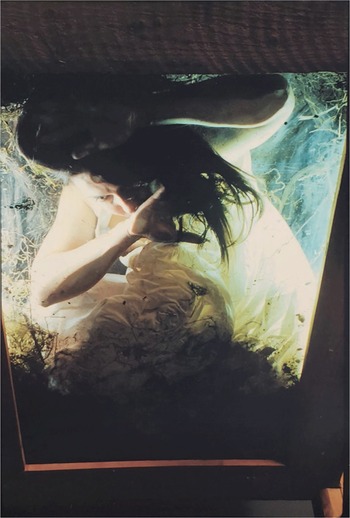

A superb example of Bucher’s theatrical/sculptural melding, Persephone Is Echo Is Narcissus (1997), was inspired by Bill Viola’s immersive tableaux films of upside-down human figures in water, specifically Stations (1994). Bucher’s performative installation featured a raised platform buttressing a fiberglass garden pond. Bucher could be seen from below lying face down, seemingly floating inside her illuminated (waterless) pond/box, on top of which was a fenced-in garden with blooming fresh flowers and vines. In the platform’s base at the ground level was a water-filled basin, reflecting the performer’s figure above. Bucher traced this performative installation to her bereavement; at the time, she was processing the impending death of her father, the art historian Francois Bucher. The motifs of death, self-gazing, and effete obsession found their mythological counterparts in the personae of Persephone (forced to perpetually reside in the Underworld six months a year), Narcissus (the gorgeous god in love with his self-reflection in water), and Echo (the nymph nursing an unrequited infatuation with Narcissus). The wavery luminescence surrounding Bucher’s supine body shines like an upside-down theatre of sorrowful reveries. Her overturned pond/garden resembles a coffin, a chamber, or a reservoir; it is a stage, sculpturally sheltering her Ophelia-like figure.

Figure 7. Claudia Bucher in Persephone Is Echo Is Narcissus. Detail view. Gallery B-12, Los Angeles, 1997. (Photo by Michelle Coe; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Like a conceptual persona, the blended character of Persephone/Echo/Narcissus enables a philosophical scientartist to efficiently convey her complex nexus of themes. An alter ego, however, exceeds the persona’s epistemic function. An alter ego allows Bucher to inquire into her alternative self-identities. Yvonne Zeeb is a case in point. The emergence of this semi-self/quasi-character derived not so much from Bucher’s invention as from a coincidence in life. In 1996, Bucher, who had been adopted as an infant, found her birth mother and learned that her birth name was Yvonne Zeeb. Having digested the significance, she presented The Pillowmap of Yvonne Zeeb (2001) in Irrational Exhibits 1, a one-evening group performance event curated by Deborah Oliver at Track 16 Gallery in Santa Monica, California. In this autobiographical light, Pillowmap both introduced Bucher’s alter ego to the public and provided a process for Bucher to know Zeeb. “I was trying to devise a method for locating Yvonne Zeeb prior to Claudia. Perhaps this relates to the action of forming language, that Yvonne existed prior to Claudia’s language acquisition, so where is Yvonne’s [physical] voice located?” (Bucher Reference Bucher2005). Pillowmap paved a path for Bucher to approach Zeeb’s distinct voice through her alter ego’s acquisition of language.

What is the intersection between language formation and voice production? Bucher’s ingenious solution in Pillowmap zeroes in on the organ through which a voice learns to produce language: the tongue. She further leaps from orality to inscription: from speech, which distributes sounds; to writing, which generates scripts. A clue to this leap lies in “Pillowmap,” the title word that pays homage to The Pillow Book, a Japanese literary text (c. 1002) by Sei Shonagon and its loosely adapted eponymous British film (1996) by the director Peter Greenaway. Bucher appreciates Sei Shonagon’s absurdist categorization of daily experiences; she also admires Greenaway’s engagement with the art of beautifully executed calligraphy (2005). Bucher used the tongue of Yvonne Zeeb to synthesize these sources.

Figure 8. Claudia Bucher in The Pillowmap of Yvonne Zeeb, Irrational Exhibits I, curated by Deborah Oliver. At Track 16 Gallery, Santa Monica, California, 2001. (Photo by Michelle Coe; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Zeeb’s tongue is the corporeal pivot on which the action of Pillowmap turned, uniting the alter ego’s action of learning to write with the artist’s installation as a mapping of this learning process. As one moving toward literacy, Zeeb learned to access and express thoughts by using her tongue to write, from tracing simple dots and lines to inscribing letters, words, phrases, and short sentences in English. In a corner of the exhibition space, Zeeb’s writing tongue, like a compass needle, oriented and converged all spatial vectors in Bucher’s triangular installation.

Pillowmap unveiled an integrated landscape where all things are connected through physical linkage and surface treatment. The three major sculptural objects—a writing station, a writing body, and an overhanging canopy—are joined like interactive organs in one cosmic body. The station is linked to the body through the writing tongue; the canopy of painterly paper canvases fans out from a pair of balsa wood model airplane wings, which are tied to the writer’s hair. The writing station, made of a bow-like spine supporting a slanted plywood board, functions as a combined music stand, desk surface, and conveyer belt, over which a long roll of rice paper draped and moved as the performer continued to write. The writer’s body leans toward the writing station, her tongue slowly alternating between dipping into colored water kept in broken eggshells and inscribing signs on the paper. The proximity of the performer’s head to her writing surface turns her station into a pillow-like object and her moving scroll into a pillow book. Overlaid on the writing motif is the navigation imagery, suggested by the airplane wings and Bucher’s boat-like stand and gestural stance.

Glue-saturated tissue paper, like a layer of alabaster skin, plasters the entire writing station. The same treatment coats the performer’s face, neck, arms, hands, and upper torso, while her lower torso merges with a throne-chair. A triangular train of paper panels, painted with colorful drawings, extends from the back of the seat to trail the ground. Like a sailboat’s rudder, the train of drawings counteracts and balances the navigator’s momentum as she leans forward to write. A triangular canopy, hung by invisible fishing lines above, features billowing paper canvases with calligraphic drawings, which float upward like a schooner’s sails blown by a fast wind, or an airborne assembly of cartographic diagrams, mapping “the place of unpleasant smells”; “the land of forgotten touches”; and other eccentric geographies. The writer’s body blends into this paper terrain.

Recalling Marcel Duchamp’s alter ego Rrose Sélavy, Yvonne Zeeb served Bucher as a conceptual persona-cum-alter ego who initially shared her biography and then acquired a semiautonomous alternative public existence. As mentioned earlier, Zeeb claimed authorship of Bucher’s MFA thesis, which doubled as a research treatise (allegedly) sponsored by the institution that employed Zeeb: the Center for Trans-cognitive Imaging/CTCI, part of the elaborate sci-fi/information art universe Bucher devised for her thesis project. Zeeb’s treatise supplies a theoretical foundation for Bucher’s fabrication of an artificial life (ALife) form named Kinocognophore, establishes a genealogy for this novel transpecies, and documents Bucher’s series of Ecosystems experiments leading to her invention of Kinocognophore (2003–2005), an ALife form functioning as the scientartist’s cognitive prosthesis to enhance her brain capacity. Zeeb further hypothesizes that the scientartist Claudia Bucher had merged with her cognitive prosthesis at some indeterminable point and no longer exists in a human form. In other words, Kinocognophore has become Bucher’s transpecies double: a surrogate-phantom alter ego–transfigured doppelgänger-hybrid.

Yvonne Zeeb solidified her presence as independent from Bucher in Ecotone (2004), a lecture performance included in On the Edge: West Coast Performance Art in the Americas, a studio art panel I curated for the College Art Association. Enlisting the curator in her narrative dissembling, Bucher requested that I introduce her to the audience as Yvonne Zeeb, a CTCI researcher. Zeeb came as a proxy for Bucher because the scientartist had vanished, probably resulting from “[displacing] herself into another life form” (Zeeb Reference Zeeb2004:5). The title of Zeeb’s report, “Ecotone,” suggested a cause. As Zeeb explained, an ecotone is an interstitial ecological region in which one might find an abundance of edge species, those harboring characteristics indigenous to the ecotone as well as those expressive of one or both adjacent areas. CTCI classified Kinocognophore as a specimen of the edge species, for it “arises from and straddles the tension zone between the biological, the machinic, the digital, the human and the animal” (Zeeb Reference Zeeb2004:3). This transorganism’s “human” constitution manifests certain traits of its creator, Bucher, and may therefore prove that the creator has merged—ecotonally—with her creation.

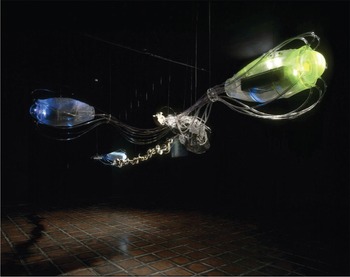

Figure 9. Kinocognophore by Claudia Bucher. Installation overview. The Center for TransCognitive Imaging, Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California, 2003. (Photo by Joshua White; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

We know Zeeb is Bucher’s alter ego: her adult clone of sorts. As an indispensable narrative device in the Kinocognophore saga, however, Zeeb must perform another role. In “Systems Poetics” (2005), Zeeb comments extensively on Bucher’s transpecies artworks and reports the scientartist as missing in her human presence. If we follow Zeeb’s testimony, then we would assume a successful transubstantiation or immaculate reconception has allowed Bucher to symbiotically merge with Kinocognophore, whose genesis resulted from advanced reproductive engineering of Bucher’s “adult” stem cells.

Thus, we come full circle, having borne witness to Bucher-Zeeb’s posthuman trinity: Bucher, Zeeb, Kinocognophore = Mother, Daughter, and their Holy Double! This posthuman trinity further evokes Bucher’s key concept, as the scientartist (the creator in absentia) extends and shares her sentience among her performance surrogates.

Movement Four: Endurance

Beyond Duration

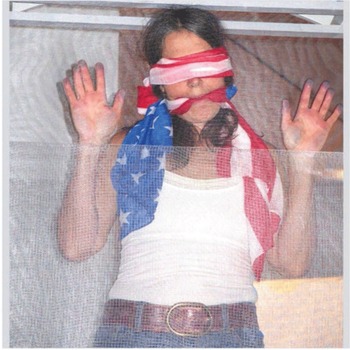

In Pod (1997), Bucher laid herself inside a giant sculpted pod that dangled from tree branches, for eight hours a day on two consecutive days. In Panoptimonium (2016), Bucher sat on top of a tower raised on three tall wooden ladders and, for an entire evening, verbally threatened anyone who climbed the ladders. In Yaw’ll Wall (2017), Bucher occupied the entrance to the group show that included it. With her eyes blindfolded and her mouth bound by US flags, Bucher stood—in a stance recalling Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man—at the center of a circle and a square, lodged inside her mobile installation: a swinging door.

Figure 10. Claudia Bucher in Yaw’ll Wall. Performance installation view. Irrational Exhibits 10: Mapping the Divide, curated by Deborah Oliver. At LACE, Hollywood, California, 2017. (Photo by Laurel Gregory; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

These aforementioned pieces exemplify Bucher’s most prevalent live art mode: endurance performance, which yields a different set of challenges for the scientartist to practice extended sentience. Similar to Bucher’s use of personas, it does not require a spectator’s leap of faith to assume an artist in a durational action to be sentient. What’s harder is for the spectator to verify that a human figure, remaining still and silent for hours, is indeed “real and alive,” rather than pretending to be so, like a theatrical mannequin under a dim spotlight. Inversely, when a performer does engage in motion, how does she extend her sentience to the props and structures in her environmental theatre?

Pod participated in SaFARi, a two-day exhibition in 1997 organized by the Foundation for Art Resources in Griffith Park in Los Angeles. Archival photos of Pod show the handcrafted vessel containing Bucher’s supine body looking both out of place and at home in the bucolic surroundings. As an artifact, the sculpture is an intruder into what we perceive as a natural environment. The sculpture is a pea pod, a canoe, and a crescent moon combined, with a curvilinear structure swelling up in the middle and tapering off toward both edges. Its surface, painted in gradations of brown, looks organic in its texture, shimmering at places of diminished viscosity and softened at others where rough patches sport elongated crevices. Given that nature is intrinsically weird, the pod is as alien as an invasive vegetation species of indeterminable origin and taxonomy.

Measured against an average-size human body, the 24’ x 2.3’ x 2.6’ pod should appear enormous. But hung beneath a giant tree, the pod appears appropriately proportioned in relation to its verdant host. Two nearly invisible aircraft cables suspend the pod from the tree, floating the sculpture among leaves and branches over a gently sloping grassy hill. Is it an oversized seed-pod vessel beamed down from outer space? Is it made for alien espionage, invasion, and eventual domination of the Earth, like those giant pod-incubators from the sci-fi cult movie, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956; remakes 1978, 1993, 2007)?Footnote 5 This association seems scarcely far-fetched, considering the hominid figure inside the vessel, exposed by the lumpy orifice that splits apart at the pod’s midriff. If the pod belongs to the dehiscent family of plants, its seed has surely taken an anthropomorphic turn. If the anthropoid figure is not a seed but a chrysalis caught in its torpid metamorphosis, then the pod is not a legume but a cocoon.

Figure 11. Claudia Bucher in Yaw’ll Wall. Detail view. LACE, Hollywood, California, 2017. (Photo by Michelle Coe; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

With eyes closed, the artist keeps her body as motionless as possible during the entire show. She covers her face and torso with clown-white makeup, yielding a thick paste that will dry to release myriad powdery shards and doughy clusters. Her skin, marred by these chalky remnants, resembles a mature sheath on the verge of molting. Will the figure burst out of her skin as a butterfly? Will she emerge as an alien double to replace her replicated human being? Will she abandon her corporeal bondage to become a spirit? Bucher’s sculpted pod-dwelling, cluttered with twigs, dry grass, spiders’ webs, together with her pallid and languid profile, suggests a nest or a coffin. Is her shelter an embryonic, incubational, or a sarcophagus chamber?

As Bucher recalls, what most interested her about performing Pod was being able to hear so many of her viewers’ reactions. Most viewers stood very close to the pod, sharing their thoughts out loud, forgetting the artist’s nearby presence. Most tried to decide whether she was “a live person or a sculpture”; some ventured that the subtle rise and fall of her chest was “animatronically produced” (see Cheng Reference Cheng2005a). Others were tempted to touch her hand, which rested on the edge of the pod’s opening. A few young boys conspired to prod her with a stick, before a guard stopped them.

By remaining motionless, an artist projects a presence not allied with the human/social world. Here Bucher appears more like a plant, in both the vegetal and theatrical senses. While we may presume a living plant to be sentient, Bucher’s prolonged lack of motion contradicts this presumption. To perform this inaction—or unaction—Bucher merged with her artwork so much so that she became an organ of Pod, like its heart, brain, or lungs, while the Pod became her second skin, her special carapace, and her sentient performance prosthesis.

Panoptimonium (2016)—“panopticon” with “pandemonium”—revisits the artist’s penchant for portmanteaus. Panopticon, originally an architectural design used for prison control, inspired Bucher’s cone-shaped tower; pandemonium characterized her action. Sitting elevated atop the tower, the performer/guard could surveil the other performances at Irrational Exhibits 9, curated by Deborah Oliver at LACE in Hollywood, California. The performer/guard in Panoptimonium further affirmed her territorial authority by verbally abusing those attempting to interact with her—as if to demonstrate Michel Foucault’s analysis of the panopticon as a symbolic social control mechanism we internalize in our everyday lives (see Foucault [Reference Foucault1975] 1995). I tried climbing the tower as a would-be audience participant in Panoptimonium, but the performer/guard’s vocal aggression, amplified through her hand-held megaphone, left me feeling exposed, confused, and embarrassed. Bucher responded to the exhibition theme of urban experiences by presenting Panoptimonium as a “psycho-spiritual synopsis” of her two-decade residence on Hollywood Boulevard in Thai Town/Little Armenia, condensed into “a kind of sculptural time-lapse snapshot” (2022d). Nevertheless, refracted through the lens of the now commonplace anti-immigration militia groups patrolling the US-Mexico borders and the virulent, Trump-fueled immigrant bashing, I see Panoptimonium as a parable for xenophobia. The performer’s incessant vocal assaults fused her fury with her xenophobic tower, both palpably hostile.

Figure 12. Claudia Bucher in Panoptimonium. Performance installation view with audience. Irrational Exhibit 9: Reports from the Field, curated by Deborah Oliver. At LACE, Hollywood, California, 2016. (Photo by Annie Martens; courtesy of Irrational Exhibits 9)

If xenophobia remains a subtext in Panoptimonium, it is a more overt political target in Yaw’ll Wall, included in Deborah Oliver’s Irrational Exhibits 10 (2017) at LACE. According to Bucher’s program notes, Yaw’ll is an “eye dialect spelling of y’all,” a contraction of you and all used as the main second-person plural pronoun in Southern American English; Yaw indicates “noun: 1. The action of yawing, especially a side-to-side movement. 2. a movement of deviation from a direct course, as of a ship. verb: (of a moving ship or aircraft) twist or oscillate about a vertical axis.” Wall signifies a construction seeking “1. to enclose, shut off, divide, protect, border, etc. with or as if with a wall […] 2. to seal or entomb (something or someone) within a wall” (2022d). The artist’s gloss explains both her design and how she utilized the revolving installation. Inserted as a barrier between LACE’s front lobby and its main exhibition hall, the viewers had to pass through Yaw’ll Wall to see other exhibits. Acting as an inevitable border, Yaw’ll Wall echoes Marina Abramovic ´ and Ulay’s Imponderabilia (1977), in which the two naked artists stood inside a door frame, forcing each viewer to face one or the other while squeezing through the guarded entrance. Bucher’s body—a component inlaid, sealed, and entombed in her monumental oscillating wall—constituted not just the door frame but the door itself.

Bucher in her blindfold invokes the iconography of Lady Justice, the personification of moral virtue in the US judicial system. Yet, her Lady Yaw’ll Wall was not blind but blinded and gagged—by US flags, no less; without the scales and sword of justice, Bucher’s Yaw’ll Wall persona summoned the quiet rage and poignancy of Langston Hughes’s poem, Justice:

That Justice is a blind goddess

Is a thing to which we black are wise:

Her bandage hides two festering sores

That once perhaps were eyes ([1932] 1994)

Replace “black” with Latine, Asian, feminist, gay, lesbian, transgender, disabled, or any other label for alternatives to the standard implied by the Vitruvian Man, and we see Bucher’s performative rendition of Hughes’s poem. In 2017, Yaw’ll Wall further alluded to the recent political campaign promise of Donald Trump, “I will build a great great wall on our southern border and I’ll have Mexico pay for that wall” (see Poynter 2020).

From an eight-hour day to a full evening, Bucher’s endurance performances customarily adopt the exhibition’s hours of operation. This trait recalls the durational pieces created by fellow performance artists, such as Chris Burden, Tehching Hsieh, and Marina Abramovic ´. As with these predecessors, Bucher places her performance art in galleries, in the context of visual arts. The artists’ bodies enact the static objecthood of artifacts, while maintaining the subjective experience of what Henri Bergson theorized as “la durée,” or “lived time” (see Phipps Reference Phipps2004). As Bucher suggests, her performing body simply functions as part of her installation, which lasts for an entire exhibition.

The scientartist’s propensity for durational work also implies that she values the expansive spacetime of performance as an unhurried sensorial habitat where both performer and viewer may pause in their own selective moments of intensity and inattention. In this intersubjective light, Bucher’s endurance performance moves toward an experiential projection evocative of Bergson’s theory of élan vital, which is conventionally interpreted as a “spiritualistic ‘vital force,’” but may be understood, from the perspective of thermodynamics, as “a tendency of organization opposed to the tendency of entropic degradation” (DiFrisco Reference DiFrisco2015:54). Whether vitalist or negentropic, Bergson’s élan vital feeds into Bucher’s extended sentience, palpable in her endurance performances.

Movement Five: Extended Sentience

Ecological Thresholds

The temporary communal bond between an endurance performance artist and her viewers shifts the spotlight from the creator to her receiver. Performance art’s chief appeal lies in the conceptual co-ownerships and imaginary conspiracy between its model pair: the artist and her viewer/receiver/respondent (see Cheng Reference Cheng2002). Extended sentience gives us a biological vantage point to consider this tacit intersubjective contract: the biofeedback necessary for an ephemeral performance artwork to have cultural impact and be recognized as part of art history. The artist extends her creative consciousness to her observer, who then carries the memory of their encounter and shares the impact of the artist’s creative labor in the expanding discursive circuit. Three of my memorable encounters with Bucher’s scientart trace my gradual assimilation of her extended sentience.

When I first saw Claudia Bucher perform—Ecosystem #3 in Irrational Exhibits 2 at Track 16 Gallery—she had transformed her allotted gallery space into a habitat centrally occupied by a hanging structure. A network of tubes, transparent sacs, and suspended objects in an assortment of glass vials constituted the structure, which was visually and systematically connected to three larger glass vessels placed on a low standing shelf. Suggestive of a circulatory system descending from sky to earth, the horizontal focal points were two transparent sacs shaped like elongated pods or enlarged squid torsos. Within one sac lay a jade plant, oozing milky substance from a small tubular insert; inside the other sac lay the artist with her arms stretching forward and her mouth connected to a catheter tube. Throughout her nearly two-hour endurance performance, Bucher slowly secreted her saliva, allowing it to drip from the catheter into a glass vessel set on the ground shelf. The dripping recurred in two other hanging containers, leaking milk from one and motor oil from the other, leaving tiny liquid pools on the ground.

Figure 13. Kinocognophore by Claudia Bucher. Detail view of 3D-printed bone, with Bucher’s body as adult stem cell. The Center for TransCognitive Imaging, Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California, 2003. (Photo by Michelle Coe; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Wrapped inside similar transparent skins, suspended at equal height and in corresponding positions, the succulent plant and the artist’s liquid-filled mammalian body assumed equivalent status as organic beings, breathing and metabolizing simultaneously. As biological organisms, they are not superior to the synthetic trappings enveloping them; they depend on those prosthetic extensions for survival. In its optimistic embrace of “organity” in lieu of humanity, Ecosystem #3 presented a cosmic ecology of various “live” forms negotiating their coexistence (see Zeeb Reference Zeeb2005:20). By projecting an empathic interconnection among all beings, Ecosystem #3 paid homage to the eco-feminist work in the late 20th century and contemporaneous understanding of deep ecology.

Bucher’s ecosystem experiments led to the putative invention of the ALife form Kinocognophore and the composition of a sci-fi scenario showcasing Yvonne Zeeb. Because of the institutional support provided by the Pasadena Art Center (where Bucher was pursuing her graduate studies), Kinocognophore has been the most high-tech among all her scientart projects—involving rapid prototyping and other virtual sculpting software and 3D printing, etc. The word itself is a portmanteau, denoting “a maker of cognitive images through cinematic means” (in Zeeb Reference Zeeb2005:10), which concisely delineated the immersive installation unveiling Kinocognophore in Bucher’s thesis project exhibition at the Art Center.

I entered a dark, narrow corridor with flickering lights from the three small video monitors that lined one wall. All monitors featured isolated processes that could have been part of laboratory experiments: the first, a palm-sized white sculpture in a petri dish gradually dissolved under liquids from a hand-held dropper; the second, a pair of hands simultaneously drawing with pencils from left and right to produce symmetrical circular patterns; the third, a pair of hands holding a scalpel to dissect a toy caterpillar. I registered these looped recordings as demonstrating various ways in which we humans (indexed by the laboring hands) acquire physiological knowledge: by dissolving surface boundaries, imaging the opaque interior, and analyzing the anatomical.

Figure 14. Claudia Bucher in Ecosystem #3: Mourning Glory. Performance installation view. Irrational Exhibits 2, curated by Deborah Oliver. At Track 16 Gallery, Santa Monica, California, 2003. (Photo by Michelle Coe; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

The corridor led to an even darker chamber filled with a sporadic mixture of oceanic and mechanical sounds. My adjusted eyesight identified an eerie, bluish-purple light periodically cutting across the darkness from cinematic projections on three walls. The projectors were hidden in plain sight, enclosed within three luminous pods, emitting colorful shimmering light. These pod-sacs were respectively hooked onto a sprawling hanging installation, like an unevenly stretched tripod, suspended in midair. A galaxy of tiny glowing specks sparkled on this strange sculpture, resembling a dinosaur skeleton without limbs, or a synthetic flying monster snake under X-ray.

Close up, I discerned the sculpture’s biomorphic physiology: the translucent pods looked like three heads; their joint body evoked some sort of vertebrae, with discrete segments, each a unique shape in bone white, simulating a living creature. Yet, the wired projectors, their acrylic stands within vinyl sacs, and the twisted strings of protruding optic fibers suggested it was a synthetic object. The three motion pictures looping on the walls deepened my categorical confusion. One cinematic sequence featured iridescent watery imagery, intercut with a pair of human hands pulling apart an entity into corresponding doubles. Another loop showed Bucher standing naked inside an imaging machine, having herself scanned from head to toe. The third looped through various close-up and wide-angle shots of cars, like a study of the transportation system.

With my memory of Ecosystem #3 still vivid, I experienced Kinocognophore as an integrated, even self-sustaining, eco-zone plus observation chamber, with its primary specimen a flesh machine, a palpably living hybrid sporting an exoskeletal spine-body, necks made of tubes, and three irradiating projector-heads. This visceral impression made me see the cinematic projections as either the hybrid creature’s memories, or expressions. As memories, the cinematic sequences implied a genealogy: cells dividing into marine animals becoming the creature’s jellyfish-like luminescence; cars, trucks, and other vehicles assembled into the transportation system and serving as the creature’s motility; the 3D scans of its creator’s full body into a pool of organic base-units that became the creature’s idiosyncratic vertebrae and organs. As expressions, the cinematic sequences attested to the hybrid-creature’s impulsive creativity, revealing its autobiographical preoccupation with marine biology, terrestrial transport networks, and photo-imaging systems. I recognized an intelligent and reflexive being, a creation in thrall to its creator. Although I didn’t see the artist Bucher’s actual body there, I sensed her presence in Kinocognophore.

The exhibition that displayed Kinocognophore as an intricate installation was only part of the information artwork entitled Kinocognophore. Bucher has created this information art saga through data accretion, adding together numerous dramatic personae (scientartist Bucher, science researcher/investigator Zeeb, and ALife hybrid creature Kinocognophore) + various videos assumed to be the hybrid’s spontaneous memories + a dramatic script (“Systems Poetics”) + a theatrical set/prop (the biomorphic sculpture Kinocognophore). To enrich my appreciation of this information artwork, I willingly followed Bucher’s dramatic simulacrum, becoming myself a dramatic character: the one who witnessed a scientartistic miracle.

What is this miracle that Zeeb, through her public lecture and written work, presented to the world?

In “Systems Poetics,” Zeeb quoted another journal entry in which the scientartist Bucher meditated on her desire for shape- and consciousness-shifting:

As opposed to theorizing about transformation, I want to work through my questions by an act of imagining, by creating a physiological hallucination. An artificial cognitive prosthetic apparatus. The drive behind the effort is the desire for transformation; transformation of being, form, consciousness, experience. (in Zeeb Reference Zeeb2005:75)

Bucher’s “desire to experience an expanded range of sensory options” motivated her creation of Kinocognophore, an ALife alter ego that enabled her transformation. While I knew Bucher’s biomorphic installation was actually a sculptural artifice, I also sensed its vitality and sentience because of its supposed kinship with the scientartist.

Zeeb cited Bucher’s journal passage to prove that the scientartist invented the ALife creature, which already bears her genes, to enable her transpecies conversion. Speaking as the director of a research team employed by CTCI, Zeeb stated, “We believe that Kinocognophore, as a prosthetic and cognitive aid, was meant to effect transformation in the scientartist through perceptual proximity and lateral exchange” (2005:74). In fact, “perceptual proximity” and “lateral exchange” explain how I felt when standing near Kinocognophore and gaping in wonder at its elegance. I freely and spontaneously offered my spectatorial zeal in exchange for its glowing magnetism. Zeeb further analyzed the process at the level of viewers like me: “There is a possibility for a transforming experience for whomever comes into contact with the poetical construct of the prosthetic (through an act of empathic attention)” (76). Empathy, a currency central to theatre arts, makes possible a spectator’s perceptions of extended sentience in Bucher’s scientart.

My experience can be understood in relation to VR immersion. In “Virtual/Reality: How to Tell the Difference,” Janet Murray argues against taking VR “as a magical technology for creating seamless illusions,” but rather as an emerging medium continuing to develop means of sustaining interaction and immersion. “The future of VR is not an inevitable and delusional metaverse but a medium of representation that will always require our active creation of belief” (2020:11). Murray’s emphasis on a participant’s belief in cocreating a parallel reality applies to Bucher’s pursuit, despite the absence of VR headsets and data gloves. Bucher’s metaphorical constructs, like VR experiences, require viewers to meet her halfway with their investments of belief and imagination. In Murray’s analysis, a critical factor in attaining “immersion in an illusion is our sense of a boundary between the real and the liminal world”; besides, we often achieve this sense of shifting realities through the aid of a “threshold object,” which “has physical existence in this world but agency in the imagined world” (2020:18). Kinocognophore was a threshold object that enabled me to perceive the exhibition hall as a biotechnological ecosystem suitable for a hybrid creature to survive. I felt its sentience despite its abiotic status as Bucher’s engineered artwork.

Figure 15. Claudia Bucher in To the Air Born? Performance installation detail view. Buckwheat Space, HWY 62 Art Tours, Morongo Valley, California, 2019. (Photo by Doug Jacobson; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

The fellowship of cosentience I perceived in Kinocognophore gave me a visceral appreciation of the interdependence of human and nonhuman lives, regarding both biotic and abiotic beings as inherently worthy components of a holistic global ecosystem. Her elegant ecosculptures explore the limit of humanity at a posthuman moment when live forms of various persuasions—from an amoeba in a pond (Ecosystem 1, 2001), an ALife creature ebullient with mnemonic genius (Kinocognophore, 2003–05), to the planet we call “Earth” (our alarmingly warming residential host, present– ?)—must negotiate our relative positions in an ecosystem that treats our coexistence as an interwoven web of symbiosis. Even so, by basing my empathy for Kinocognophore on our comparable sentience, my analysis reveals a bias toward life, taking sentience as a sign of living. To the Air Born? (2019), another multiphased, cross-genre project, questioned this assumption from a paradoxical angle: Is the choice to refuse entering a state of sentience an expression of extended sentience?

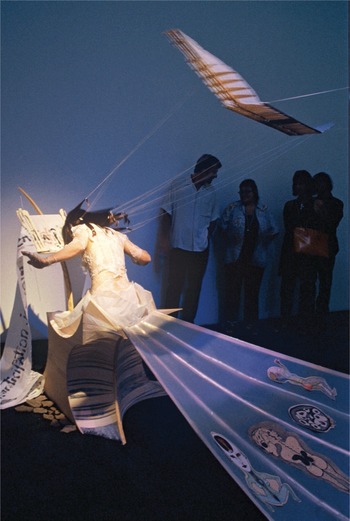

To the Air Born? combined three thematic/compositional elements: wind-propagated entities, such as anemochores and kites; the Guatemalan Giant Kite Festival in celebration of the Day of the Dead; and increasingly restrictive antiabortion legislation in a plethora of US states.Footnote 6 Bucher fused these elements into the persona of an embryonic amalgam of an anemochore and a kite, pondering whether or not to be air-born/e. During a month-long residency at the Buckwheat Space in Morongo Valley, California—a location known for forceful crosswinds—Bucher first made small triangular kite-like sculptures that featured colorful drawings simulating the molecular and cellular shifts as the anemochores meditated. Into each kite sculpture she inserted a human face mask, perhaps suggesting an artist’s inquiring spirit. As her residency coincided with the HWY 62 Art Tours, an annual desert-wide open-studio art exhibition, she also created two larger open-air sculptures (made of fabric, wood, rocks, and PVC pipes), including a wind-dispersal apparatus used to carry her for her culminating five-hour performance entitled, “To the Air Born?” DAY of the DAEMON Celebration (Deliberating Anemochore Embryos Manifesting Ontological Noesis) (20 October 2019).

Bucher’s title decodes her embryonic anemochore-kite’s action as deliberating its own existential viability (aka, ontological noesis/consciousness), a contemplative act crystallized in the bold-faced acronym: DAEMON. According to Bucher’s program notes: “Daemons are benevolent or benign nature spirits, beings of the same nature as both mortals and deities, similar to ghosts, chthonic heroes, spirit guides, forces of nature” (2019). Bucher related her “daemon” to the Greek “daimon,” citing from James Hillman’s use of the Greek term as the unique code/imprint/imagery guiding an individual soul in his “acorn theory”: “The acorn theory says that the ‘daimon’ selects the egg and the sperm, that their union results from our necessity, not the other way around” (in Bucher Reference Bucher2019).

Figure 16. Claudia Bucher in To the Air Born? Performance installation overview. Buckwheat Space, HWY 62 Art Tours, Morongo Valley, California, 2019. (Photo by Evi Klett; courtesy of Claudia Bucher)

Provocatively—if without verification—Hillman reversed the cause-and-effect relationship between progenitor and progeny, setting his scene prior to the act of conception when one’s daimon chooses the parental vessel to undergo procreation. Bucher set her mythic scene in To the Air Born? at a later moment, after the initial act of fertilization when her anemochore-kite has reached the embryonic stage; she nevertheless leaped from Hillman’s supposition that a preborn entity might engage in deliberation about its “necessity” to be born.

Clad in white and exposing at its core a bird nest–like organ formed of coiled ropes, like umbilical cords stored inside a uterus, Bucher’s embryonic amalgam precariously perched on top of a giant kite skeleton, balanced between staying put and being blown over by the constant wind. Bucher listed a series of questions in the program, revealing her own attitude toward the antichoice movement’s advocacy for the unborn’s “right” to be born: “How can the living make assumptions about entities that are not able to actually give consent about anything?”; “Do the unborn deliberate on whether to be born? Do they contemplate their own viability?”; “What if fertilized forms are mostly antinatalist and would prefer to avoid existence?” (Bucher Reference Bucher2022d). Although Bucher challenged the antiabortion advocates’ presumptuous assertion of fetal personhood, her embryo’s ability to ponder its viability ironically gives a similar agency to an unborn entity. By immersing her preborn persona in extended sentience, without the presence of a maternal body or a surrogate uterine nurturer, Bucher’s dramatic scenario inadvertently echoes the antiabortionists’ strategy to prioritize an unborn’s putative personhood over the agency of the pregnant person. To the Air Born? at once exposes a blind spot in the antiabortionist argument for fetal rights and showcases a preborn entity’s deliberating awareness. The instability of the wind-resistant structure Bucher inhabits appears symptomatic of the complicated, and occasionally precarious nature of moral, political, and even artistic doctrine.

In Bucher’s assessment, To the Air Born? was a partial failure because she had insufficient resources (funds, labor, and time) to use nonwhite fabrics. She conceived her giant kite costume as colorful, not the billowing white robe she wore in the actual performance—a symbolic color inevitably conjuring the Christian iconography of a martyr-cum-savior. While I find her prochoice argument outlined in the program vulnerable to critical scrutiny, her silent, chimeric figure in performance remains an enigma. Amplifying her hybrid persona’s elusive presence, her white costume also evokes the blank page of a scroll, the empty canvas before a colorful stroke, and the waiting screen on my computer. Her failure, if there was one, serves as a point of inception for others, opening a space for their reveries.

Bonus Movement: Roundabout Reciprocity

A Reflexive Encore

22 October 2022: I was filled with excitement in anticipation of Claudia Bucher’s performance at HWY 62 Art Tours in the Joshua Tree National Park communities in Southern California (see Arts Council 2022). Bucher had mentioned to me a few weeks prior to the studio tour event that she might pursue a performance sequel to To the Air Born? (2019), so I was duly surprised to see a sculptural installation in her barn-converted studio/theatre, Mojavetia.Footnote 7

A gigantic headdress, made of symmetrically placed cactus areoles, stems, spines, and pads in gradations of green and brown, assembled with a pair of elongated curvy palm fronds, thrusting forward like elephant tusks resting prickly on the ground. A centrally placed wooden seat and two footrests, all painted white, protruded like an extension from the white wall on which the headdress was attached. A stiff cactus branch pushed out from the seat to reach the ground. This headdress configuration reminded me of the central core imagery prevalent in the California feminist art circles in the 1970s, except for the erect “pubic” branch, which I could not but perceive as a blatant phallic symbol. As Bucher informed me, the shape of her headdress was a mash-up of three inspirations: the traditional spiky floral crown worn by unwed Ukrainian women, the mask and headdress worn by the Silvesterklaus during the New Year’s Eve festivity in Switzerland, and found objects from her own desert-living property and environment. Her live performance, which she planned for the next day and the last date of the HWY 62 Art Tour, would consist of “activating the headdress” with her embodied personification as a warrior goddess (Bucher Reference Bucher2022f). Responding to my query about the “phallic pubic branch,” Bucher identified the grounding cactus stem as, instead, a “bursting clit,” stretching from the vagina (2022f). My knee-jerk Freudian invocation met Bucher’s corrective matriarchal sensuality, forcing me to shift from my acculturated phallic bias to a rarely pronounced yonic reference. Through this feminist lens, Bucher’s enlarged cactus-clitoris is kin to Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll (1975).

F.L.U. Season (2022), presented to the public in Mojavetia on 23 October 2022, exhibits several of Bucher’s artistic trademarks. Her verbal wit is alive with her punning title. We are indeed in the peak of a flu season, while simultaneously Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has raged on. Bucher’s acronym title urges us to “Fight Like Ukrainians,” combating “the narcissistic bullies and coercive misogynists in the world with your inner Ukrainians” (Bucher Reference Bucher2022g). Adept at translating her life circumstances into art, Bucher joined her two paternal keystones—her Ukrainian birth-father and her adopted father who was Swiss—with her own Mojave high desert life. While her stupendous headdress stands alone as an awe-inspiring sculpture, her four-hour endurance performance (lasting from 12:30–4:30PM on a wintry Sunday) to “activate”—i.e., to make sentient—the static crown with her furiously sonorous body was, to many of us who witnessed her real-time artistry and physical prowess, beyond awe.

Unlike many of her voiceless performance personas, Bucher’s Warrior Goddess in F.L.U. Season is wrathful and loud. Even before stepping into her barely insulated barn/theatre, I heard some aggressive guttural howls reverberating in the chilling wind. The Warrior Goddess sits on her throne, with her face fully covered in a collaged mask of multicolored fabric, her hands and palms dyed red (by the crimson juice from prickly-pear cacti), and her mud-caked feet firmly planted on the stirrups midair.Footnote 8 Seemingly in a trance or maniacally possessed, the performer grunts, curses, and vocalizes in an alien language, her muscles tense with exertion, her fists pounding, her arms at times pushing an invisible horde of enemies out of her way, and at others gesturing toward self-disembowelment, as if to exorcise those who haunt and taunt her. I felt at once chilled to my bones and exalted in my spirit. While bundled up in my layered jacket, I could hardly withstand the ceaseless winds assaulting our semi-open shelter. In contrast, Bucher wore a loose-fitting top, with her midriff bare, evidently immune to the wind-chill factor. Did her dedicated physiological dynamism, fueling and sustaining her impressive vocal and kinetic performance, serve to raise her body temperature? I left the raging Warrior Goddess after 30 minutes, hoping to avoid the risk of hypothermia and the relentless LA traffic on my homebound drive. Yet, even after I completed my three-hour journey home, I realized that Bucher’s F.L.U. Season performance was still in progress. Her personification of sound and fury, with almost superhuman stamina, in an imagined terrain of Mojave-Switzerland-Ukraine would continue for another hour.

Bucher’s triple-heritage Warrior Goddess joins the rank of her myriad hybrid creatures of extended sentience, presenting us yet another of her threshold objects in an ecotonal performance. Let me risk an osmosis-induced metaphorical word-game here: Bucher’s information art evokes a paradigmatic architectural structure built for transition and exchange: a bridge. Hers is an intricately paved two-laned bridge: one lane allowed the scientartist to deeply embody an alternative form of existence; the other lane—in sync with, parallel to, disrupting, or intersecting the authorial lane—was where her spectators could vicariously ingest a gift of her sentience: creativity.

Bucher has generated an expanding menagerie of inscrutable amalgams that have taken me through ecosystems within, across, and beyond unnamable wormholes. She has created artworks as prosthetic extensions of her creative daemon. Are my words, which propagate her artworks in the world, her prosthetic extensions as well? Approaching from the reverse end of this discursive circuit, do my words find their “necessity” through Bucher’s scientart? Isn’t her oeuvre—in a nutshell or an acorn—my conceptual persona, my symbiotic double, enabling me to spawn my philosophy?