It is traditional to begin this presidential address with some autobiographical background, if only to provide some context for what is to follow. Chris McKenna rightly likes to remind us regularly that few of us self-identify as business historians. In this respect, it is fair to say that I would not be here today if it was not for me getting a position at the University of Glasgow. Until I moved to the university, my research had focused on the making of government economic policy, in particular the Keynesian revolution. At Glasgow, the long tradition of business history research had been formalized in the creation of the Centre for Business History in Scotland a year before I arrived and led then by Tony Slaven. And so, another “business historian” was belatedly born. However, to return to Chris’s anecdote, for me, it is not just an issue of self-identification. About fifteen years ago, an esteemed professor of business history said to me (and with no malice intended or taken): “Neil, you are not really a business historian, are you?” Today, I am happy to swear my oath of allegiance to the field, whether or not this article convinces you of my business history credentials.

I was born in Brighton but then moved frequently around southern England, until at the age of six my family arrived in Croydon, where my parents lived until they retired. We moved frequently as my father’s career progressed. He began as an apprentice in the building trade but worked his way up, so that by the time we moved to Croydon he was a building estimator. I have yet to come across anyone else who has had this job, so I had better explain what it was. He would estimate the costings and then the price of a construction project. This estimate then formed the basis for the company’s tender submitted to the client to try to win the contract. He worked in this role for some of the largest UK construction companies at a time when they were internationalizing. I remember hearing about his trips to various parts of the world, but my sister and I were taken only to Swansea University in Wales and High Wycombe, just outside London.

Why do I tell you this? Looking back on his anecdotes about his job and the industry, it is clear that economic power and political power were strongly evident. Although bids were blind, it was clear that there was sometimes a degree of collusion or at least ballpark knowledge of other companies’ likely bids; and, at times, companies would take turns to try to win contracts. It was also an industry in which incomplete contracts predominated—on a project my father would have ongoing working relations with architects, subcontractors, and the clients, often being involved in follow-up meetings as the building specifications changed or simply to catch up on the developing cost of the project, but always where this was an ongoing negotiation.

All of this is evidence of economic power, but it also merged into political power. The industry famously kept a shared list of ostracized workers linked with trade unions or the left, and it employed the right-wing group the Economic League to spy on suspect workers. When this was closed down, it set up its own organization that operated from the 1990s until 2009, and for which the industry has just paid compensation to some of the workers who were boycotted for over twenty years.Footnote 1 More generally, the industry was known for strongly supporting right-wing or neoliberal think tanks and various other similar activities. Unsurprisingly, it not only had close links with the Conservative Party but was also very active in the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), which was the main representative body of business in the United Kingdom.Footnote 2 The industry often prompted the CBI to push infrastructure projects as an area for further public investment. When threatened with nationalization in the 1970s, my father, like other employees, came home with a sticker for his company car and balloons advertising the merits of the industry.

More seriously, he also mentioned bribery with regard to some of the international projects. The power of these individual companies and the industry as whole resonates with the theme of the address.

After much self-debate I ended up with the title, “‘The Vast and Unsolved Enigma of Power’: Business History and Business Power.” There are many similar such phrases about power, but this one is from Adolf Berle.Footnote 3 I was tempted to use another of his quotes—“Power, next to sex and love, is perhaps the oldest social phenomenon in human history”Footnote 4—but I thought it might give you a misleading impression of what follows. However, this alternative title does link better to the person, other than me, most to blame for this topic: the UK’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who certainly loves power, and seems to love sex too.

So, why Boris Johnson? In June 2018, the then foreign secretary responded to concerns raised by business about Brexit with the immortal phrase “F*** business,” prompting headlines like “‘F*** business’: Boris Johnson is accused of dismissing concerns of UK job losses in foul mouthed comment to EU diplomats”; and from the Financial Times’ Facebook page, “‘Fuck business,’ Boris Johnson is reported to have said, putting himself at odds with any normal sense of what the Conservative Party stands for.”Footnote 5 It also resulted in a cartoon that won 2018’s UK Political Cartoon of the Year Award, but the joke, a spoonerism referring to Bucks Fizz, the British winners of the Eurovision song contest in 1981, might be lost on a non-UK audience.Footnote 6

A source close to Johnson subsequently elaborated that he had been misheard; he was actually attacking lobbying groups like the CBI.Footnote 7 Certainly, since becoming prime minister, he has deliberately snubbed the organization on a number of occasions. But the same can be said of his attitude to business more generally. Even the City of London got nothing like the relationship that it wanted with the European Union in the post-Brexit negotiations.Footnote 8

Yet, in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in the world, the common belief is that business is dominant and its power is out of control, particularly in the case of big business and multinationals. Nor is this limited to popular opinion as the titles of these books well illustrate: Gangs of America: The Rise of Corporate Power and the Disabling of Democracy; Unchecked Corporate Power; Monopolized: Life in the Age of Corporate Power; The Political Power of Global Corporations; and The Political Power of the Business Corporation. Footnote 9 Some of these books may be polemical, but others are serious works by respected senior scholars. Stephen Wilks, the author of the last of the list, for example, is not only one of the leading scholars of business regulation in the UK but also served as a member of the UK Competition Commission for eight years. The preface to his book is telling, but typical:

In 1974, when I first became intrigued by the power of business corporations, and particularly by their ability to wrest concessions from national governments, it seemed perfectly possible to bring these concentrations of economic power under democratic control. Now I’m not so sure. It seems to me that many of the democratic gains fought for so heroically over the last 150 years have simultaneously created a set of nominally economic forces which have emptied many of those gains of real meaning. The truly worrying prospect is that those forces, call them corporate capitalism, managerial dominance or simply corporate power, have created new autocrats, immune from effective popular control. Business corporations are often creative and can be brilliant and enriching, but their economic and cultural achievements cloak their ability to dictate political choices. This is far from an original insight.Footnote 10

As business historians, we well know the accuracy of that final sentence, especially for the United States with the cacophony of calls for action against business power during the Gilded Age and subsequently.Footnote 11 The exercise of business power is evident in many areas of business history, from business lobbying and interest groups, to multinational interactions with home and host nation governments, to monopolies and cartels and calls for deregulation, to the study of business networks, interlocking directorates, and business elites.Footnote 12 At the same time, as I will show, most business historians have been reluctant to take on the issue of business power directly and explicitly. Despite working on business-government relations and the collective action of business, I am as guilty of this as anyone else.

In many respects, this reluctance is both understandable and justifiable given that many social scientists are also unwilling to analyze power directly. The subject is too abstract, unfalsifiable, and empirically quite difficult to operationalize. As Culpepper noted in 2011, “The study of business power is currently more neglected than it has been for the last half century.”Footnote 13 Thus, many social scientists have followed the line of the historical institutionalist Kathleen Thelen in shunning “‘the language of power’ in favor of identifying the interests and coalitions on which institutions are founded [because], unlike power, actors and their interests are more tractable empirically.”Footnote 14

Despite this, I would suggest that now might be the time for business historians to visit, or revisit, the study of business power. Why is it timely? For several reasons. First, as Adolf Berle suggested, power is a fundamental issue and should be a fundamental issue for business historians. To ignore it or only to engage with it implicitly relegates what should be a core topic of the field to the periphery. Second, it is clear that there has been a reinvigorated interest in the subject among social scientists since the global financial crisis.Footnote 15 Even Kathleen Thelen is now writing on business power.Footnote 16 Third, and finally, there is evidence that business historians are beginning to talk about power more frequently in their work, but it remains rather unfocussed and often implicit.

This article will begin with a brief discussion of the main core approaches to the theory of business power and explain the problems that have subsequently been highlighted. It will then turn to considering the areas of business history in which business power has been addressed. The third section outlines some of the main recent developments in the social science literature that have emerged with the reinvigoration of interest in the topic of business power. The final section suggests how these new developments offer the potential for new insights for business historians by illustrating how these approaches are informing my own work. It is hoped this will act as a prompt to open a wider conversation about business history and business power.

Approaches to Power and Business Power

Stewart Clegg and Mark Haugaard entitle their introduction to The Sage Handbook of Power, “Why Power is the Central Concept of the Social Sciences.”Footnote 17 They are not alone in making this type of bold statement.Footnote 18 Others emphasize its centrality to organizational studies, to political science, and to research on international relations.Footnote 19 Nor is this simply a recent view; back in 1950, Harold Lasswell and Abraham Kaplan wrote that “political science, as an empirical discipline, is the study of the shaping and sharing of power.”Footnote 20

Yet, as Adolf Berle and others remind us, this centrality does not make it any easier to study—it remains an enigma. It is an essential concept, but one that needs to be explained rather than do the explaining.Footnote 21 Many of the world’s key thinkers have contributed to the debate on power, from Aristotle to Hobbes, Machiavelli, Marx, Nietsche, Weber, and Gramsci. More recently, so have Dahl, Parsons, Galbraith, Bourdieu, Habermas, and Foucault.Footnote 22 All have offered important insights, but none have provided a definitive theory of power. Indeed, such an exercise might be fruitless. Thus, Haugaard, following Wittgenstein, suggests that power is a “family resemblance” concept.Footnote 23 Such concepts do not share a single unifying characteristic but, like members of a family, “embody a cluster of concepts with overlapping characteristics.”Footnote 24 With no single definition covering all usages, meaning is defined by the particular context in which it is used, and it changes significantly in different contexts.

Nevertheless, although a minority view today among power theorists, there is a common and resilient view of power as domination or control in which coercion and the exercise of power is key, or what is often referred to as “power over” or “control over.” This is most associated with Robert Dahl’s definition of power as “A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do.”Footnote 25 Those in this tradition focus on who prevails in conflictual decision making as being more powerful. Two year later, in his article on business and politics, Dahl makes clear that this definition is driven by the desire to find a discrete and testable definition rather than one that encompasses all aspects of the power and influence of business.Footnote 26

Unsurprisingly, therefore, Dahl’s approach was criticized for being too narrow, and this developed into the famous “Three Faces of Power” debate. Dahl’s was the first face, the second was developed by Bachrach and Baratz in the 1960s, and third face by Steven Lukes in the early 1970s.Footnote 27 The second face was that the powerful could prevail by setting the agenda and by reinforcing existing rules and norms and not just by concrete action. Lukes then broadened the argument by highlighting how power shapes the way in which people perceive their wants, desires, and interests, and how people come to accept the existing order: power’s third face.

Significant as this debate was in expanding conceptions of power, much empirical research continued to rest on Dahl’s position. This is visible in the vigorous debate in the United States from the late nineteenth century over the power of business.Footnote 28 As big business grew, so too did its economic power, with just a few corporations dominating a sector and then increasingly the whole economy. The “tentacles” of big business enveloping US political institutions is a common metaphor for the period, as was the notion of the government as a puppet in the hands of big business. However, it was not just an issue of economic scale. As Berle and Means famously illustrated, it was also that this economic power was in the hands of a management class increasingly divorced from ownership.Footnote 29

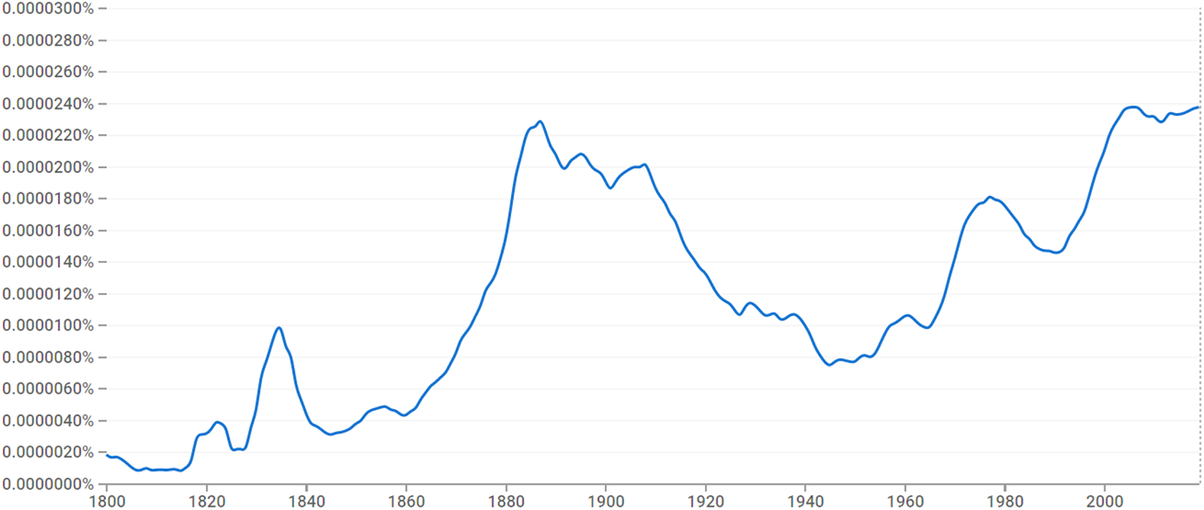

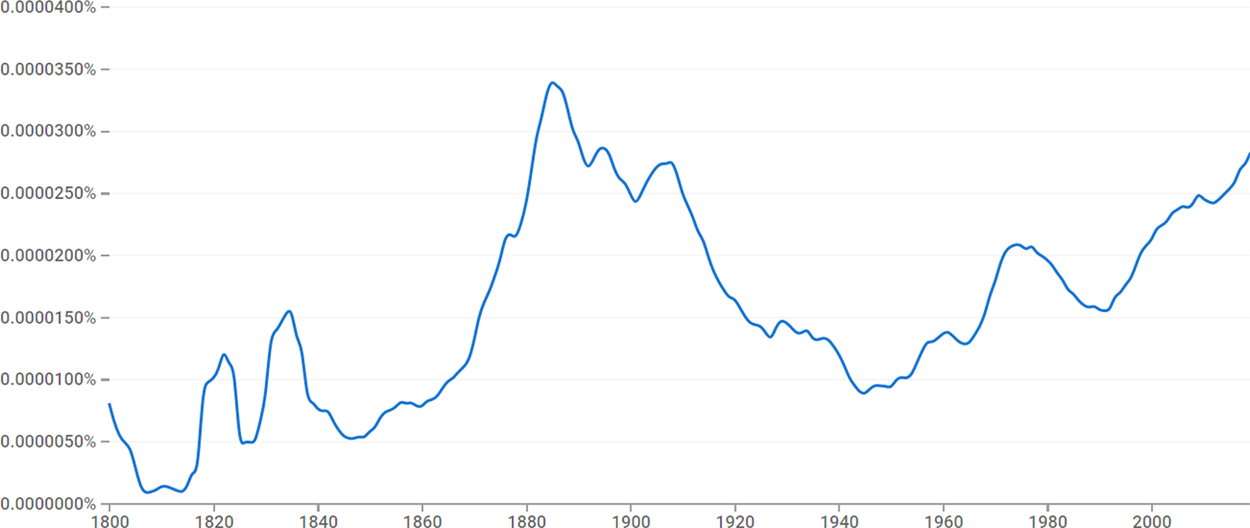

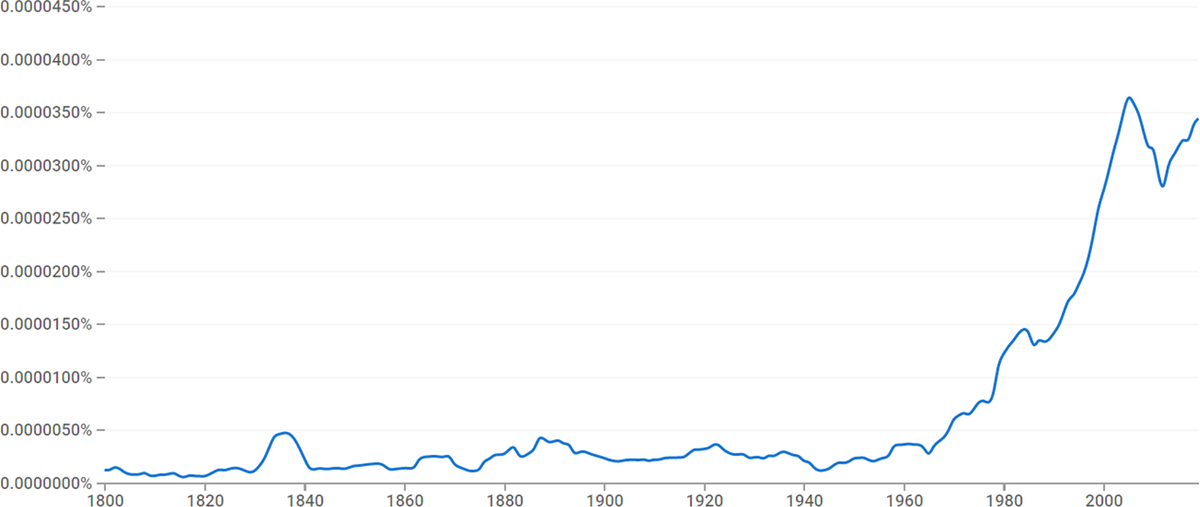

Figure 1 is a Google Ngram that shows how significant the issue of business power (actually, it is largely corporate power) was relative to other topics in terms of usage of these key terms in books published each year.Footnote 30 It peaked in the late nineteenth century, returning to the same level of significance only at the turn of the millennium. In reality, as Figures 2 and 3 show, there are two trends here, visible when we split English language into American English and British English.Footnote 31 Corporate power was an issue in books published in the United States from the nineteenth century, becoming less significant from the early 1900s until the 1950s and then rising steadily thereafter (apart from a dip in the 1980s). In contrast, it was not an issue in British-English books until the 1960s, but it has risen rapidly since then and is now at a higher percentage than in American-English books.

Figure 1. Google Books Ngram with search terms business power + corporate power + power of business + power of corporations, 1800–2019 (in English and smoothed)

Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer (http://books.google.com/ngrams)

Figure 2. Google Books Ngram with search terms business power + corporate power + power of business + power of corporations, 1800–2019 (in American English and smoothed)

Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer (http://books.google.com/ngrams)

Figure 3. Google Books Ngram with search terms business power + corporate power + power of business + power of corporations, 1800–2019 (in British English and smoothed)

Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer (http://books.google.com/ngrams)

As shown in Figure 2, concerns about business power and its implications for US democracy reappeared after World War II. Seminal here was C. Wright Mills’s The Power Elite, published in 1956.Footnote 32 As the Ngram shows, it is at this time that writing about business and corporate power began to take off again in books printed in the United States. Wright Mills’s contribution sparked continuing interest in the issue of national elites and the role of businesspeople.Footnote 33

However, criticisms of such examples of instrumental business power began to appear. Crucial here was acknowledgment that power could exist without such intentional action (that is, instrumental power). This opened the way for the development of structural concepts of power, and structural business power was one of the key areas where the concept developed. Two separate literatures emerged, both arguing that instrumental power, like elite access and lobbying, were insufficient explanations of the privileged position of business in society. Both promoted the idea of structural power, and that this position reflected the structure of capitalism and the special position of capitalists in that. One was a debate among Marxists,Footnote 34 the other of Charles Lindblom’s Politics and Markets. Footnote 35

Lindblom famously argued that business had a privileged position in society because governments depended on business to deliver employment, growth, and economic success. Failure to deliver this positive economic outturn would politically harm the popularity of the government, and so governments would give special attention to the needs and wants of business. Reductions in investment, or awareness of that possibility, represented the structural power of private business. Governments would factor this automatically into their policy making. Business power did not, therefore, rest solely on the tools of instrumental power, such as lobbying and campaign financing.

However, just as there were problems with instrumental power, so there were problems with structural power too; these problems were, if anything, greater. First, there was a problem of being overly abstract and, with that, the difficulty of empirical falsification.Footnote 36 How did one show that structural power had or had not occurred? In this respect, structural power was like the elephant in one of those old jokes:

Why do elephants paint their toenails red?

I don’t know. Why do elephants paint their toenails red?

To hide in cherry trees.

Have you ever seen an elephant in a cherry tree?

No.

Shows how well it works!

The power’s very invisibility showed how effective structural power was.

A second problem was pointed out by David Vogel. He offered a trenchant critique of the concept because business was not always successful and business power rose and fell over time.Footnote 37 Similarly, Mark Smith showed that even when the US Chamber of Commerce spoke with a united voice, it still did not always win.Footnote 38 The concept of structural power could not explain these variations in experience across time and place. Also, it was incredibly difficult empirically to distinguish between instrumental and structural power. As a result, the concept fell out of favor to such an extent that structural considerations were increasingly presented as merely context for the operation of instrumental business power.Footnote 39 Even capital strikes—that is, private businesses’ refusal to invest, an idea at the very heart of structural power—became described as an example of instrumental power. Studies of instrumental power, mainly of political lobbying and campaign financing, remained the dominant approach to the study of business power thereafter.

However, a problem remained. There was a paradox that empirical research increasingly illustrated. While businesses spent large sums of money on gaining preferential access to policy makers, businesses often failed to achieve their specific goals; and yet still, at a broader level, they seemed to hold a privileged position in society.Footnote 40 A pluralist understanding of business power seemed to hold sway in academic research, while the general presumption was that this was clearly not the case and that business power seemed to be ever increasing, especially in the context of globalization.

Business History and Business Power

With this in mind, I now turn to business history’s engagement with business power. As noted in the introduction, there are many areas of business history that directly relate to the concept of business power, and I want to flag some of the more obvious ones, if only briefly. Early examples relate to the chartered companies, most notably the East India Company, but also other British chartered companies and their foreign counterparts.Footnote 41 Powerful as they were, these were individual companies, they were few in number, and they were trading with other parts of the world.

The issues raised were more politically acute with the spread of the franchise and the rise of legal considerations that related to the general form of the corporation. Since the nineteenth century, as many here know better than me, these issues have been at the heart of a longstanding debate about democracy and the corporation in the United States. Unsurprisingly, this has spawned an extensive literature; most notable, in recent years, is Naomi Lamoreaux and William Novak’s 2017 edited collection, Corporations and American Democracy, but there are many other noteworthy contributions that have developed our understanding of corporate governance and regulation more generally.Footnote 42 As Richard John has reminded us, Alfred Chandler believed this relationship was so adversarial in the United States because big business preceded big government in a way not found elsewhere in the world.Footnote 43 Nevertheless, historiography on the regulation of business and corporate governance in other countries has developed markedly in recent years.Footnote 44

We have also seen historical studies of business elites both nationally and transnationally and a huge literature on multinationals.Footnote 45 Many of these works are underpinned by assumptions about power and its distribution; in the case of multinationals, these often have a clear political dimension to their narratives. They usually consider the relations between the company and the host nation government, but some consider relations with the home government, too. Some point to the power of multinationals, while other highlight issues of political risk.Footnote 46

Finally, there are the more directly instrumental acts of business power studied, most obviously in the form of lobbying. Here, the works of Ben Waterhouse, Jennifer Delton, and Kim Phillips-Fein stand out, but again there are many more—whether they look at cases of lobbying or at business support from right-wing movements and think tanks as part of campaigns against perceived excessive state interference in business people’s ability to operate in a world of “free enterprise.”Footnote 47 There is an equivalent literature dealing with lobbying of the institutions of the European Union and its predecessors and of national governments beyond the United States.Footnote 48

This is just a brief illustrative list of some of the areas of business history that clearly are underpinned by some notion of business power. In other words, business power is a relevant concept to much existing business history research. And this is without even touching on other obvious aspects of business in which power relations are key: employer-worker relations, gender, race, and imperialism, for example. The point I wish to emphasize at this stage is that power is dealt with implicitly and indirectly in the majority of this historiography, if it is dealt with at all. Like many social scientists, business historians seem reluctant to face the concept of business power head on.Footnote 49

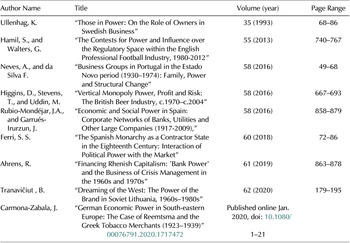

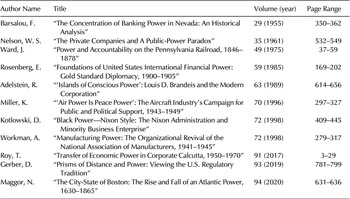

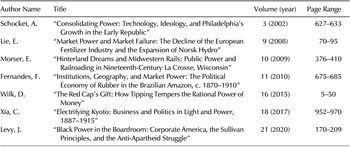

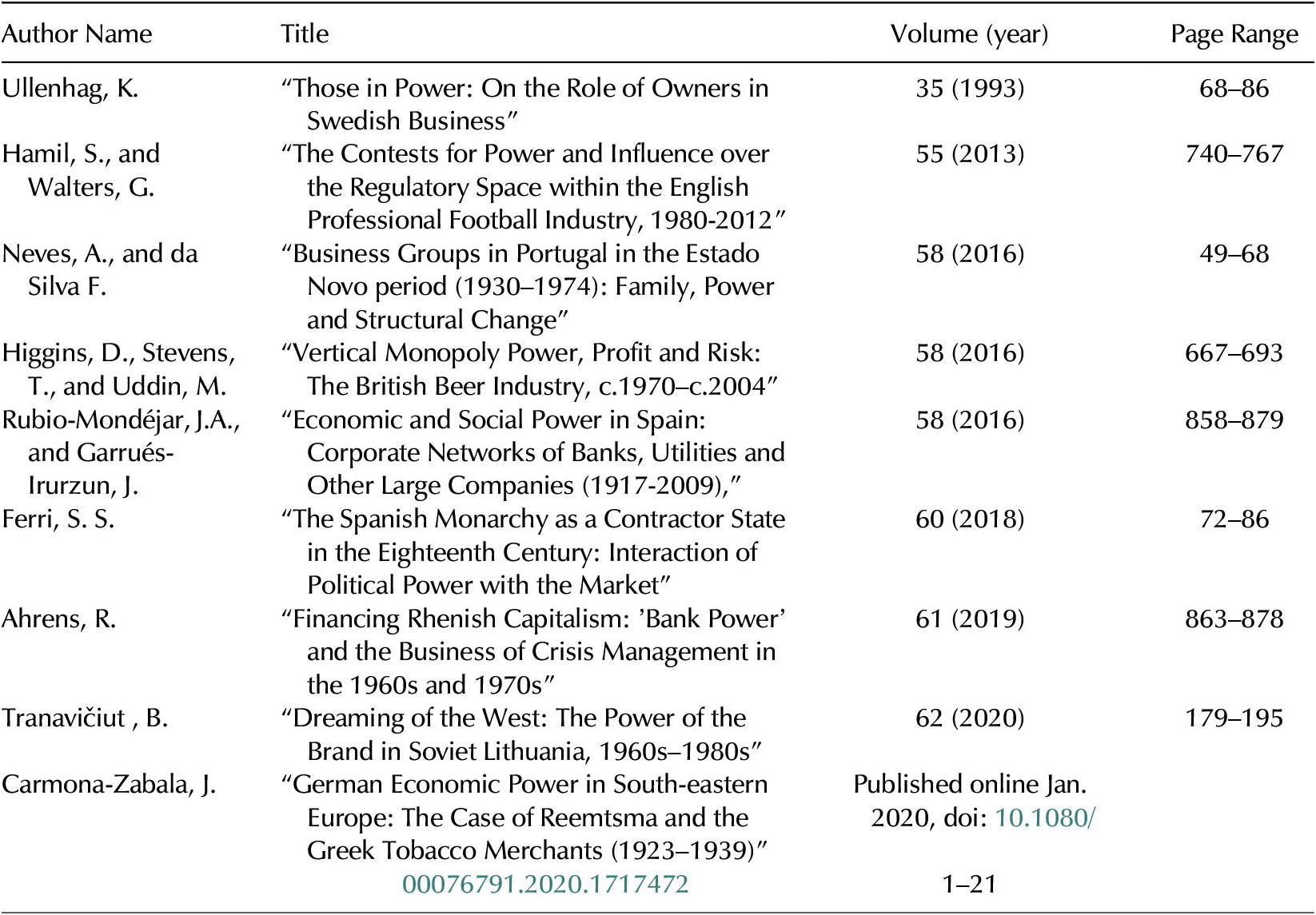

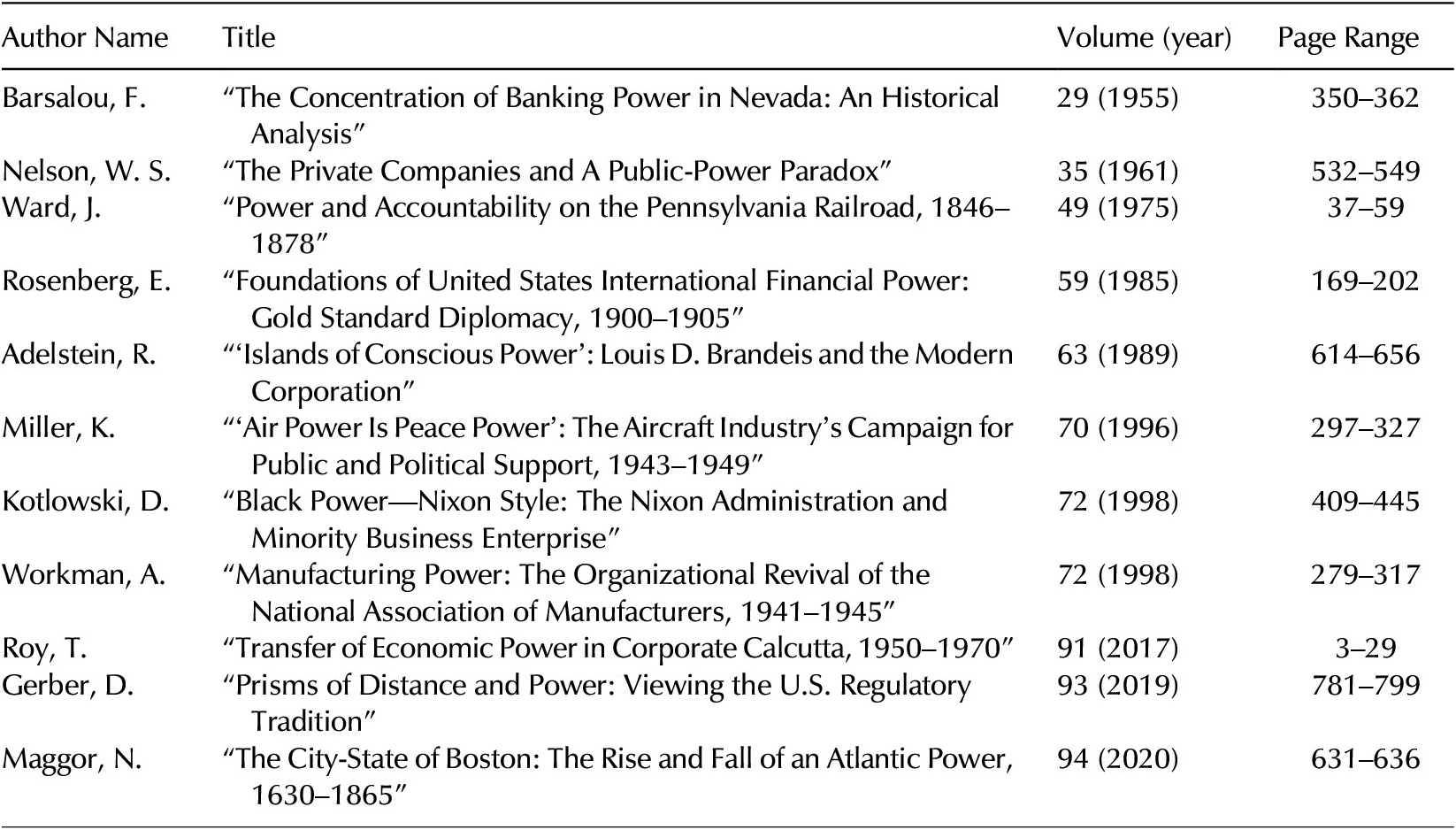

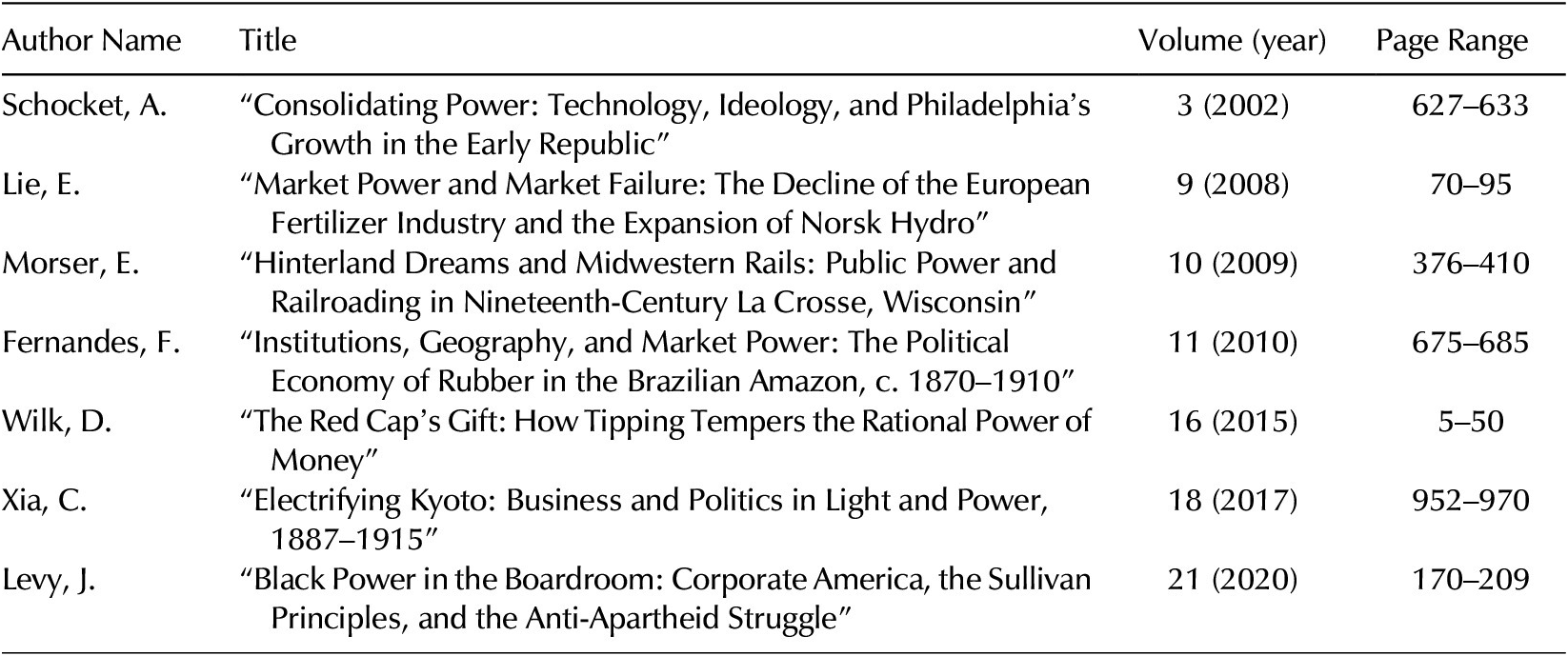

Indeed, I am surprised at just how infrequently it has been the focus of work in the field. The following tables aim to illustrate this point, though a more compelling case would require deeper research. If one looks at the articles published in the subject’s leading journals, Business History, Business History Review, and Enterprise and Society, the lack of articles about business power is palpable. Tables 1–3 show the articles published in the three journals with “power” in their titles (book reviews, some other short pieces, and articles on power as energy have been removed). Each covers the whole period of the journal available online and using the search term “power.” On this evidence, power is not a key concept in business history research. Personally, I was astonished at how few articles there were.

Table 1. Business History from 1958, 9 articles

Table 2. Business History Review from 1926, 11 articles

Table 3. Enterprise & Society from 2000, 8 articles

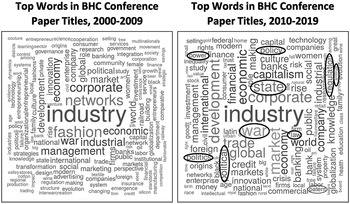

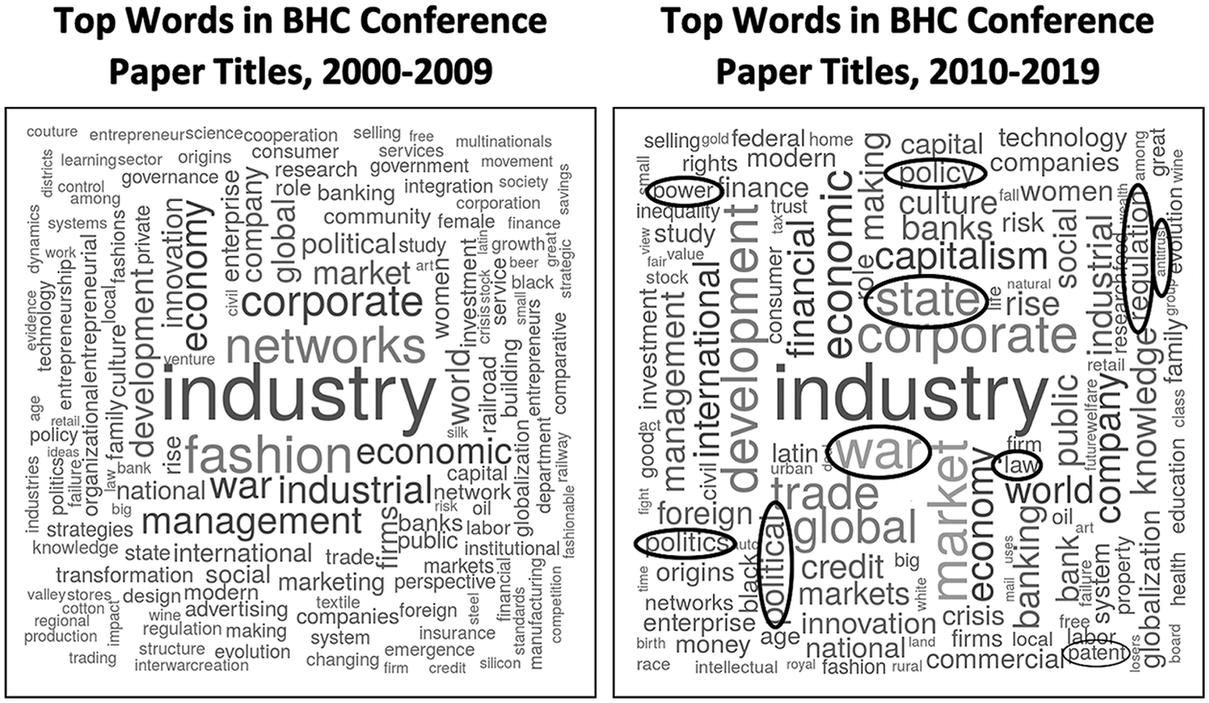

Similarly, Figure 4 reproduces one of the word clouds from Ed Balleisen’s presidential address last year.Footnote 50 Power does not appear as one of the most common words between 2000 and 2009, and it remains pretty small for 2010 through 2019 (circled in the top left-hand corner). Nevertheless, Balleisen’s point was to show how the topic of state–business relations is an emerging field of research in business history.Footnote 51 It is clear that in all three journals and in conference paper titles, the word “power” is appearing in titles more frequently, though starting from an exceedingly low base.

Figure 4. Growth in focus on business-state interactions in BHC papers, 2000–2019

Source: Balleisen 2020, 834.

One explanation for this might be the rise of research on the history of capitalism. It is often noted that power is an important aspect of work in this field.Footnote 52 Thus, Seth Rockman notes, “‘The market’ is a euphemism for actual economic actors (people) and institutions (law and culture) that shape how economic power is exerted and experienced.” He continues that the concepts of financialization and commodification “impel scholars to excavate the relations of power that underlay what can be bought and sold (and by whom and on what terms) at a given moment in history.”Footnote 53

Likewise, Julia Ott has said, “As historians, we embrace agency and contingency. . . . But we are also attuned to the significance of power relations for structuring economic life, for privileging certain forms of economic knowledge, and for shaping outcomes.”Footnote 54 Later in the same exchange, Sven Beckert suggests, “Power in all of its dimensions is crucial.”Footnote 55

Yet, the concept of power being referred to here as so crucial remains ambiguous, opaque, and potentially inconsistent. For some, it seems to be material-resourced control power (that is, power over), whereas Ott’s distinction between human agency and power hints at some form of structural power. I have no problem with historians using different conceptualizations of power. This takes us back to Wittgenstein’s notion of power as a family resemblance concept. However, given this, it is incumbent on historians who argue that power is important to make explicit what their conceptualization is. Otherwise, we run the risk of being back with elephants and cherry trees.

I believe that there is a window of opportunity here for business history to develop its understanding of power in general and of business power in particular. Andrew Popp and Susanna Fellman have recently published on a stakeholder perspective of power, the archive and organizational history, in which they question notions of control power.Footnote 56 Here, I want to use a different illustration: Paige Glotzer’s recent book on the racial segregation of housing in Baltimore, Maryland. At its outset, she states: “At its heart, this book is about power—how it is gained, how it is deployed and then how it shapes resource distribution. Scholars frequently emphasize the role of state power in shaping housing. Markets, like government, are ‘the result of power and an arena of power.’”Footnote 57 Coming back to this theme, having elaborated the long-lasting role of the Roland Park Company in the construction and maintenance of racial segregation, she concludes:

Block by block, through informal networks and institutions, it [the Roland Park Company] helped construct a market wherein the most valuable property, the most resources, and the greatest amount of social, cultural, and political power all accrued to white people in planned suburbs. Together with policymakers, developers helped to build suburban power around an exclusionary housing market—a market that persists to this day. Housing segregation may be persistent, but it is not immutable. By looking at its history, it becomes clear that it was never inevitable, nor is its continuation.Footnote 58

There are a number of points I would like to draw out for emphasis from this statement. First, while there is reference to resources, power is also presented as relating to relationships. Second, the outcomes of power relationships are mutable, and hence so are those power relationships. Agency, context, and contingency are, therefore, key constituents in these power relationships. In other words, there is uncertainty in the construction and evolution of these power relationships. Third, it highlights that the relationship between business and government in the United States was not simply adversarial but also was more complex and diverse. On occasion, it takes the form of working together, even of partnership, which highlights notions of “power with” rather than just “power over.” And, finally, because there is human agency, power can be found everywhere. On my reading, this is less like Dahl’s control power and much more like a Foucauldian conceptualization of power, where there is no binary divide between those with power and those who are powerless. These points all relate to a more nuanced and complex understanding of the concept of power in general and business power in particular. But this understanding could be taken further.

Recent Developments in the Study of Power and Business Power

To that end, I now turn to some recent developments in the study of business power. I am well aware that these are only one or two strands of a much larger literature, but they are the ones that relate closest to my own research field of business-government relations and that I have found most helpful.Footnote 59 I begin with Clarissa Hayward’s critique of the Three Faces of Power debate:

We should define power . . . as a network of boundaries that delimit, for all, the field of what is socially possible. . . . To de-face power is to emphasize . . . that social boundaries to action circumscribe all social action. Mechanisms of power—boundaries that, by my view, include but are not limited to institutional rules, norms, and procedures—define and delimit fields of action. They do so, not only for those who seem powerles . . ., but also for . . . apparently “powerful” agents.Footnote 60

Significantly, she then adds:

Power relations might, to a greater or lesser extent, enable those they position to act in ways that affect their constitutive boundaries. Students of power should consider the extent to which, and investigate the ways in which, particular relations of power enable and promote this social capacity for action upon boundaries to action.Footnote 61

In other words, power defines the range of possibility, but actors have scope within those boundaries to take actions, which can shift those boundaries depending on their creativity and agility in finding innovative ways of changing those power relationships. This means an uncertain world and the possibility of unexpected outcomes. An uncertain world, Katzenstein and Seybert argue, “frustrates a multitude of leviathans exercising control under assessed conditions of risk,” provides opportunities for other actors to acquire power, and leads to unexpected outcomes.Footnote 62 Here we have human agency, contingency, and diversity of outcomes.

We also need to think about the potential diverse forms of power relationships beyond “power over”; that is, to add “power to” and “power with.”Footnote 63 We need to think about mutual or reciprocal dependency-type relationships. As an example, rather than thinking simply about the power of multinationals, Bohle and Regan have recently argued that there were tacit bargains between these multinationals and the state in Ireland and Hungary in terms of their tax treatment in return for investment, creating a mutual dependence form of structural power.Footnote 64

This interdependent approach to power has been important in the reinvigoration of research on structural business power. Hacker and Pierson started this in 2002, but it really only took off after the global financial crisis and the reconsideration of business structural power in the light of the bank bailouts, the notion of “too big to fail,” and globalization.Footnote 65 Structural power, as seen today, is quite different from the overly abstract and general concept put forward by Lindblom in the 1970s. It is variable, not constant, depending on context; it is a signaling device rather than something that dictates government policy, and business is not viewed as monolithic.Footnote 66 The mediating role of perceptions of structural power is also now seen as important, introducing ideas like perceptions of business confidence.Footnote 67 One significant way in which structural power is seen to vary is the political salience of the issue, as highlighted by Culpepper in his influential book Quiet Politics and Business Power, and this approach has already been found helpful by some business historians.Footnote 68 He argues that if an issue has low traction with the public, or what he terms “quiet politics,” then business is more likely to achieve its goals. If, however, the issue is or becomes a popular concern, then life becomes harder for business.

This relates to a third element of business power that is sometimes suggested—discursive power, which is akin to ideational power. Actors, including business, have the ability to influence policy through lobbying the public in order to frame a debate. If business can establish a dominant public discourse, governments are likely to respond with more business-friendly policies. The ability to achieve this will vary across countries and sectors as well as over time.Footnote 69

Finally, Kathleen Thelen proposes a further type of business power: institutional business power.Footnote 70 This power comes from business’s role in the provision of the key public goods and services that they provide following delegation by government, either by government deregulation or by its own accretion. Over time, government becomes ever more dependent on private provision of these goods and services.Footnote 71 Although relating to contemporary developments, I can see potential historical applications, such as to private chartered companies, for example.

None of these new developments in studying business power make it simpler. Nevertheless, in drawing out issues of mutual dependencies and attempting to address contextual differences, contingency, and uncertainty, I would argue that we start to see a framework that is more likely to appeal to historians. There is the possibility of a more nuanced understanding of the factors involved in explaining the nature and extent of business power in different settings. It also means that narratives can move beyond one-dimensional accounts of adversarial relationships between business and government, even though these remain a key element of the story. Significantly, one article revisiting Culpepper’s work compares the role of business in the 1975 and 2016 referenda in the United Kingdom on membership into the European Economic Community/European Union.Footnote 72 The history is not its strength, but the piece does effectively show how these conceptual advances can be insightful, notably by highlighting the impact of changes in the coordinating ability of business and its legitimacy over time.

Business History and the New Approaches to Business Power

In this spirit, I would like to illustrate how these new approaches are helping me in my own research as a way, hopefully, to stimulate a more explicit engagement with business power by business historians. I look at three cases.

The first relates to the action of British clearing banks to the threat of nationalization in the 1970s. This is ongoing work with Vicky Barnes and Lucy Newton. In this case, we can see how the clearing banks moved from a position in which they relied on the Bank of England to represent their interests to government to one in which, faced with this perceived existential threat, the banks embarked on discursive campaigns with the public, bank staff, and consumers to highlight the banks’ contribution to society. This was complemented by a raft of lobbying activities of members of Parliament and ministers, while the banks also explored the possibility of moving assets and activities out of the United Kingdom. Thus, there was a move from a more general form of structural power to more instrumental and discursive business power. This prompts questions about the ways in which business perceives it power and the extent to which it is aware and able to adjust its power relationships. Also, in relation to Culpepper’s ideas about quiet politics, the banks had a clear preference for such an approach but regarded a public campaign to raise the salience of the issue as its “nuclear option.”

The second case relates to the Confederation of British Industry and Margaret Thatcher. The conventional account makes clear Thatcher’s dislike of the CBI, which she regarded as a body tainted with 1970s corporatism.Footnote 73 The CBI was, it is commonly argued, cast to the political periphery with very little access to, let alone influence on, the government. However, it is obvious from Margaret Thatcher’s appointment diaries and other sources that she continued to meet with the leadership of the CBI in private and intimate meetings on a frequent basis. I argue that this was because the government had to rely on the CBI to achieve wage restraint, so the government had to provide regular access in return. But there was a second element to this interdependent relationship. The CBI’s survey of business confidence was the key guide to business sentiment, and its results were reported widely in the press. This provided instrumental power that led to access to senior ministers, discursive power in framing the debate about the state of the economy, and structural power. The government had to factor these into its thinking, as well as into institutional business power, since, through a process of accretion, the CBI’s survey had become the nationally accepted measure of business confidence. Adopting a business power perspective has helped me gain insights I had previously missed and also highlights the remaining difficulty for empiricists in distinguishing between different types of business power.

The final example is a broader one, and it reflects my current developing project. It relates to the interaction between business and government. It is customary to refer to the hollowing out of government with the rise of neoliberalism: privatization, contracting out, and public-private partnerships all became more common. But in the British case, and I think more widely, this trend began earlier and was part of a wider movement whereby in all sorts of government activities, private business developed growing influence. This took multiple forms involving business actors, business ideas, and business methods.

For example, before the 1980s we see: (1) the emergence of the use of management consultants in government from the 1960s, (2) a growing sense of the “revolving door” as a normal experience for retiring government officials, (3) the appointment of business people to key advisory roles at the heart of government, (4) the development of secondments into business for bureaucrats and vice versa for business people, (5) private meetings between leading business people and their equivalents in the civil service, and (6) shared common training programs at junior levels aimed to increase mutual understanding and create lasting social networks. Some of these developments provided straightforward opportunities for lobbying and are evidence of instrumental power, but there is something more general here, too. Other parts of society did not get treated in the same way and feedback effects only strengthen that position within government, such that the boundary between the private and public became fuzzier. As a result, we get some understanding of how Boris Johnson can dismiss business concerns while doling out lucrative contracts with little oversight to private companies.

To conclude, I have touched on only a few strands of the literature on power by focusing on business power and the political dimensions of the subject. There is much more out there. Hopefully, I have persuaded you that while business power is an enigma, its importance is such that we must address it head on and explicitly in our work. In the past, this was not the case, but there were clear reasons for that. Within the business history community, there does currently seem to be a growing sense of engagement with notions of power and the questions that it raises, so it is important to build on that.

With regard to business power more specifically, the recent developments in thinking that I have tried to outline, do make it more relevant to business historians. However, it is also necessary for us to move beyond simple notions of control power to think about how the power of business affects all types of relationships and is also omnipresent in all businesses’ exchanges. Methodological obstacles remain, but the topic’s importance means that we cannot continue to leave it in the shadows. And, to end on a positive note, business historians have much potential to contribute here. Though not an historian, Cornelia Woll concludes that “historical narratives and process tracing remain the most useful techniques” for studying power and influence.Footnote 74

Competing Interest

None.