To the Editor—The use of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) is crucial in preventing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to healthcare workers (HCWs) when caring for COVID-19 patients. However, the debate on the importance of different modes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 continues, and it affects the type of PPE recommended for use. Reference Wilson, Norton, Young and Collins1 Moreover, with this pandemic still in progress, the issue of conserving PPE is a practical dilemma. 2 Clinicians are naturally concerned if they are asked to undertake a procedure potentially generating aerosols while using droplet precautions. Countries and specialist societies define and specify the list of aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs) differently. In practical terms, a risk assessment is needed for some procedures with borderline risk such as nasogastric tube insertion. Although the recommendations of PPE for known or suspect COVID cases is clearer, there is greater uncertainty regarding precautions for nonsuspect cases, especially in high-prevalence settings.

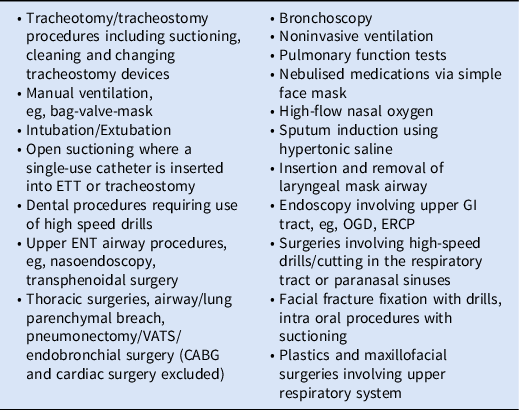

The Singapore National Infection Prevention and Control Committee developed a list of “Procedures of Concern” (Table 1) to help HCWs identify procedures of higher risk that require additional measures to prevent transmission from unidentified COVID-19 cases in the hospital for other reasons. The risk is dependent on the procedure, community prevalence of COVID-19, proportion of diagnosed and isolated infections, and healthcare facility–level screening.

Table 1. Procedures of Concern

Note. ETT, endotracheal tube; ENT, ear–nose–throat; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; GI, gadstrointestingal; OGD, oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Procedures of concern are defined as any medical procedure that can induce the production of aerosols of various sizes, including small (<5 μm) particles containing SARS-CoV-2. For all other procedures, standard precautions should apply. During periods of low community prevalence, the emphasis should be on the use of standard precautions. 3 In general, AGPs and procedures of concern should be avoided in patients with suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19, unless urgently required. Ideally, these should be performed in an airborne infection isolation room (AIIR) whenever possible. Reference Pollán, Pérez-Gómez and Pastor-Barriuso4 When unavailable and the procedure must occur in situ (eg, intubation during resuscitation), staff are advised to draw the privacy curtains and remove any shared equipment, supplies, or linen from the immediate vicinity prior to performing the AGP. In addition, the number of HCWs who are present in the patient’s room during an AGP should be limited to only those necessary to safely perform or assist in the procedure.

At some stage in the pandemic, there is a point of community prevalence at which the risk of an asymptomatic COVID-19 case presenting for an AGP increases sufficiently that all patients should be regarded as suspects for the purposes of infection prevention and control and contrariwise as the epidemic wanes. Because the acceptable risk may differ by procedure, our recommendation is to couple a country-specific per-patient risk of undiagnosed SARS-CoV-2 infection, π, derived from epidemiological data, with a procedure-specific risk threshold, θ p . When π < θ p , nonpandemic guidelines can apply for procedure p, but when π ≥ θ p , pandemic-level measures should be implemented. Although the risk π of a patient having undiagnosed infection is not known, a conservative upper bound can be derived. Seroprevalence in mid-2020 suggested ˜10-fold more infections than cases, though this has probably fallen as more testing has been done. 3 Assuming an infectious period of 10 days and, conservatively, that all infections are asymptomatic, the number of asymptomatic infections in the community would be 100 times the daily incidence of newly diagnosed cases. For instance, if the daily incidence of diagnosed COVID-19 is ˜200 per day in a country of 20 million and there have been ˜2,000 diagnosed cases in the previous 10 days and at most 20,000 undiagnosed but infectious individuals, up to 1 in 1,000 patients would be expected to be asymptomatically infected (π = 0.1%). For an AGP with greater risk, the threshold might be set at 1 in 100,000, in which case the incidence would be sufficiently high to warrant pandemic measures. For lower-risk procedures, standard measures could be considered. The rule of thumb (multiplying diagnosed cases by 100) is deliberately simple and in most settings conservative because, in reality, symptomatic cases are likely to be identified through screening and case detection is likely to have improved over the first year of the pandemic.

We report a practical approach to assist HCWs in determining risks and identifying procedures of concern. There are still gaps in evidence regarding SARS-CoV-2 transmission routes, risk to HCWs, and safety of AGPs. Reference Jayaweera, Perera, Gunawardana and Manatunge5 PPE guidelines written in the context of an evidence gap and of high professional anxiety may cause unnecessary waste of PPE. Moreover, necessary clinical interventions may be unnecessarily cancelled which may result in poorer outcomes for patients. Areas experiencing high rates of transmission should be necessarily conservative in protecting HCWs undertaking procedures of concern. At this stage of the pandemic and moving forward, many countries have or will have improving prevalence, and some guidance to de-escalate infection prevention and control measures for procedures in nonsuspected cases will be needed.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.