Introduction

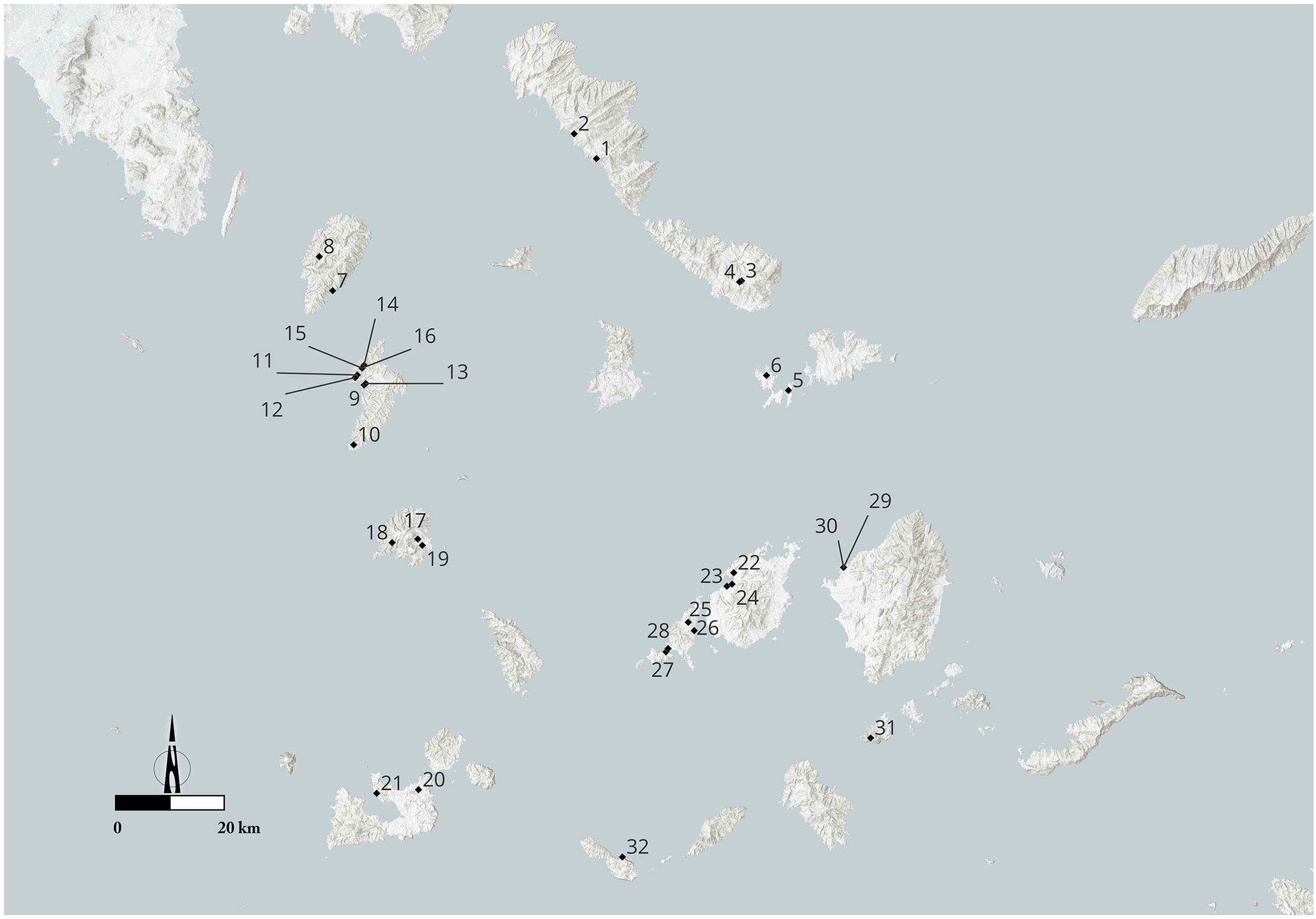

The Cyclades, a group of 220 individual islands and islets in the middle of the Aegean Sea, have a long history of activity, the earliest traces of which belong to the Middle Palaeolithic period. Human occupation on the islands was continuous from the Neolithic era throughout antiquity. Since the 1960s the results of numerous rescue and systematic excavations started unveiling the past of the archipelago, which continues to trigger research interest especially during the last decades (Mazarakis Ainian Reference Mazarakis Ainian2017a; Angliker and Tully Reference Angliker and Tully2018). The results of recent archaeological work in the Cyclades provided new, important evidence for the islands during the historical period and fuelled theoretical approaches concerning community formation on a micro and macro level, insularity, networks, and movements of people, goods, ideas, and technologies (Map 8.1 ). The last decade saw the continuation of a number of systematic excavations on particular islands (for example, Kythnos, Andros, Tenos, and Despotiko), the initiation of new surveys and archaeological projects, as well as important publications of old and new material and data. Moreover, an emphasis has been put on the preservation, restoration, and enhancement of buildings and archaeological sites.

Map 8.1. Map showing sites mentioned in the text: 1) Zagora, Andros; 2) Palaeopolis, Andros; 3) Xombourgo: Vardalakkos, Tenos; 4) Xombourgo, Tenos; 5) Delos; 6) Rheneia; 7) Karthaia, Kea; 8) Agia Marina, Kea; 9) Vryokastro and Vryokastraki, Kythnos; 10) Maïstralia, Kythnos; 11) Kolonna, Kythnos; 12) Kastraki, Kythnos; 13) Fykiada, Kythnos; 14) Profitis Ilias, Kythnos; 15) Aspra Spitia, Kythnos; 16) Aspra Kelia, Kythnos; 17) Chora: Bofiliou plot, Seriphos; 18) Aspros Pyrgos, Seriphos; 19) Livadi: Perseus guesthouse, Seriphos; 20) Kouphi, Melos; 21) Melos: ancient theatre; 22) Marapas, Paros; 23) Paroikia: south necropolis, Paros; 24) Floga, Paros; 25) Ag. Kyriaki, Antiparos; 26) Glypha, Antiparos; 27) Mandra, Despotiko; 28) Tsimintiri; 29) Chora: Plithos, Naxos; 30) Chora: Aplomata, Naxos; 31) Ag. Ioannis Cave, Irakleia; 32) Chrysospilia, Pholegandros. © BSA.

Northern Cyclades

Andros

Zagora

Almost 40 years after the first excavations conducted between 1967 and 1974, the Department of Archaeology at the University of Sydney, the AAIA, the ASA, and the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, returned to the Early Iron Age settlement of Zagora (Fig. 8.1 ). The new fieldwork programme operating since 2012 aims to investigate sustainability and societal change at the settlement with the use of both non-invasive and invasive evaluative techniques (ID12967). Through geophysical testing of the subsurface remains, geological evaluation of the promontory, archaeological surface survey, and trial trenches, the overall urban layout of the settlement and a new topographical plan were prepared. The investigation of the social and economic structures of the Early Iron Age settlement is central to the project’s aims.

8.1. Andros. Zagora. Plan of the Geometric settlement. © Zagora Archaeological Project/S. Paspalas.

A surface survey, additional to that of 2012, conducted in the hinterland of Zagora, indicated that the occupation was concentrated within the fortification wall, while no such traces were detected beyond the fortified area. The subsurface anomalies in the sector explored with thermal/infrared imaging might indicate the presence of graves. During the 2014 excavation season, the remains of a workshop came to light, further explored in 2019, while a large concentration of faunal remains seems to point to the existence of another working space in the area. The material recovered provides important information on the first phases of occupation of the site in the Geometric period (Beaumont, Miller and Paspalas Reference Beaumont, Miller and Paspalas2012; Beaumont et al. Reference Beaumont, McLoughlin, Miller and Paspalas2014).

Palaeopolis

The systematic excavation conducted by the University of Athens at the ancient polis of Andros, at the modern site of Palaeopolis, celebrated 30 years in 2017 (Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa Reference Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa2018a) (ID2622, ID8516, ID6611, ID6192, ID6190, ID5056, ID4614, ID3060). Located almost at the mid-point of the island’s west coast, the polis covered an area of ca. 60ha, extending over a steep, terraced slope. Parts of the fortification wall, buildings, and streets have been uncovered so far, revealing the history of the island’s capital, particularly from the Classical period onwards. The research of the last decade has focused mostly on the agora of the polis, which occupied a flat area by the seashore (Fig. 8.2 ). Parts of four roads (I–IV) and 10 buildings (A–J), extending over two terraces, were uncovered. Building activity began in the fifth century BC, but the agora developed primarily after the late fourth century, with its main phase placed in the first half of the second century BC. The archaeological finds, together with the epigraphic evidence, revealed the multifaceted roles of the agora, related to the polis’ administrative, commercial, and industrial life and cultic practices. A foundry, a fish market, and a possible butcher’s shop, a temple dedicated to an unknown deity, and an altar (?) of Zeus Maimaktes have been identified. Hellenistic and Roman monuments occupied the open space in front of the buildings and the roads. The excavation uncovered the well-organized drainage and water-supply system of the agora, whose use must have changed in the second half of the fifth century AD, as indicated by the foundation of the Christian Basilica (Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa Reference Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa and Giannikouri2011; Reference Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa, Chankowski and Karvonis2012; Reference Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa, Voutiras, Papagianni and Kazakidi2017; Reference Palaiokrassa-Kopitsa, Angliker and Tully2018b).

8.2. Andros. Palaeopolis. Aerial view of the agora and harbour areas. © L. Palaiokrassa.

Tenos

The systematic excavation at Xombourgo by the University of Athens under the direction of Nota Kourou continued on two terraces at the southwestern part of the hill (2009–2010) (ID2068, ID2633, ID4220, ID5054, ID6613, ID8517, ID8160, ID17424): Terrace AA, where an open-air cult space has been reconstructed; and Terrace E, where the large Building E with two architectural phases was investigated. The remains of an Archaic building were found east of the ‘pre-Cyclopean sanctuary’, as well as a paved street leading to a monumental staircase of the Archaic era heading to Terrace E (Kourou Reference Kourou, Étienne, Kourou and Simantoni-Bournia2013).

Since 2013, the systematic excavation has focused on the Classical necropolis, located at the site of Vardalakkos, east of Xombourgo, which N. Kontoleon had already excavated in 1955 and 1958 (Fig. 8.3 ). The remains extend over two successive terraces, on either side of the road leading to the settlement, each with a different function: Classical funerary monuments are found on the upper terrace; tombs on the lower terrace (Kourou Reference Kourou2017; Reference Kourou, Frielinghaus, Stroszeck and Valavanis2019).

8.3. Tenos. Xombourgo. Aerial view of the necropolis at Vardalakkos. © N. Kourou.

Most of the tombs on the lower terrace were tile-graves, co-existing with cist graves, two sarcophagoi, and numerous enchytrismoi. The graves were poorly furnished and marked with unworked stones. Fire remains between the tombs suggest funerary rituals. In comparison, on the upper terrace a series of built, luxurious structures of various types meant to support funerary monuments were found along the funerary road. Many stelai came to light in 2019 in a destruction layer of the fourth century BC, including the stele of a naked youth and another depicting a bearded, naked man accompanied by a small child holding a bird, both works of local sculptors. The finds and the monuments testify to the development of a rich necropolis in the fourth century BC, following the Athenian model, which remained in use until the end of the third quarter of the third century.

A rectangular building was found behind these monuments, possibly used for rituals performed in the necropolis. Below the building’s floor, two rows of pits of various shapes and uses came to light, indicating the existence of a metallurgical workshop operating in the Archaic period, which must have been abandoned after the beginning of the fifth century, when the first graves appeared on the lower terrace. The finds suggest that the metal processed in the workshop was iron, with the discovered pits and related finds representing the smelting phase.

Delos

On Delos, excavation work and research has continued in the last decade. Four excavation seasons have been dedicated to the ‘Maison de Fourni’ (2010, 2012, 2014, 2019), aiming at deciphering its function (ID1954, ID3405, ID4769, ID8590). Built towards the end of the second century BC, it is special due to its architectural features and the richness of its decoration. Initially considered a domus pseudourbana (an urban-looking house in the outskirts of Delos town), the re-exploration of the Maison de Fourni revealed a villa, which did not only provide luxury accommodation, but also played an important role in the storage, processing, and transmission of agricultural products between the city and the countryside (Wurmser Reference Wurmser2016–2017). In 2021, a mission was dedicated to the detailed architectural study of the house through plans and photogrammetric documentation of its components, allowing the best possible understanding of its development, organization, and integration in its landscape.

A three-year underwater survey, the first to be conducted around Delos, was initiated by the Institute of Historical Research of the National Hellenic Research Foundation in collaboration with the EUA in the context of the Marie Curie project UrbaNetworks (2014–2016) (Fig. 8.4 ) (ID6585; https://urbanetworks.wordpress.com/). This project explored the submerged parts of the Stadion and the Skardana districts, developed in the Late Hellenistic period on the northeast and northwest areas of the island respectively. The underwater investigation showed that commercial harbours operated in both districts, complementing the activities of the central harbour in the west part of Delos.

8.4. Plan of central Delos indicating the structures found in the bays of Skardana and Stadion during the 2014–2016 underwater survey of the EUA in collaboration with the National Hellenic Research Foundation. © EfA/drawing by E. Kontogiannis on the basis of Moretti et al. Reference Moretti, Fadin, Fincker and Picard2015, pl. 5.

Seven ancient shipwrecks – six of the Late Hellenistic period and one of the Roman period – were located in 2016 in the course of a preliminary deep-water underwater survey north of the bay of Skardana, in the strait between Delos and Rheneia, and along the east coast of the island of Rheneia (Zarmakoupi and Athanasoula Reference Zarmakoupi, Athanasoula, Simosi and Sotiriou2018) (ID5226, ID8500, ID8588).

A new collaborative five-year underwater project has been initiated by the French School in Athens, the EUA, the National Hellenic Research Foundation, and the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (2017–2021) (ID6781). Aims of this project include the documentation and excavation of the submerged areas of the main harbour of Delos, the location of shipwrecks around Delos and Rheneia, and the geomorphological investigation and bathymetric mapping around both islands to comprehend their maritime landscape and to identify the trading networks of the Late Hellenistic and Roman era. Architectural remains were detected in the north zone of the modern port, as well as at the level of Dioskoureion. Moreover, five Hellenistic and Roman wrecks were detected along the east and west coasts of Delos.

A number of research projects – the study of the hippodrome, the urban morphology, and geology and architecture of stone roof structures – have also been running on Delos under the auspices of the EfA.

A project for the protection and enhancement of the archaeological monuments of Delos was initiated in 2016 by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports through the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades with the aim of turning the island into an open museum. The restoration of a number of monuments, including the Menodoros Monument, the monumental Hellenistic Stoa of Philip, the Temple of Apollo, funded by the Athenians in the late fifth century BC, the Granites Palaestra, and the richest private house of Delos, the House of Dionysos, is either completed or still in progress.

The last years saw the completion of a number of monographs in the Exploration Archéologique de Délos series (for example, Étienne Reference Étienne2018), as well as synthetic studies dedicated to various themes (for example, Karvonis and Malmary Reference Karvonis, Malmary, Chankowski and Karvonis2012; Reference Karvonis and Malmary2015–2016; Reference Karvonis, Malmary, Chankowski, Lafon and Virlouvet2018; Moretti Reference Moretti2012; Reference Moretti and des Courtils2015; Brun-Kyriakidis Reference Brun-Kyriakidis2014; Moretti et al. Reference Moretti, Fadin, Fincker and Picard2015; Moretti and Fincker Reference Moretti, Fincker, Fellmeth, Krüger, Ohr and Rasch2016; Zarmakoupi Reference Zarmakoupi, Chankowski, Lafon and Virlouvet2018; Moretti, Fraisse and Llinas Reference Moretti, Fraisse and Christian Llinas2021; for details, see also Moretti Reference Moretti2019).

Rheneia

The Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades returned to the small island of Rheneia, 120 years after the first excavations of the late 19th and early 20th century on the island (ID8595). The new fieldwork programme, which began in 2019, includes an extensive surface survey throughout the island, the creation of a geological map, and the documentation of the old excavations. It also involves excavation work at Chomasovouni, at the southern part of the island, where marble architectural members and the foundations of a building were visible prior to archaeological investigation, probably belonging to the, epigraphically attested, ‘Artemision on the island’ (Fig. 8.5 ). Within the scope of the new project, all Byzantine, post-Byzantine, and modern remains will also be documented.

8.5. Rheneia. View of the Hellenistic necropolis of Delos on Rheneia, the pyramid-shaped hill of Chomasovouni where the site of the Artemision on the island is likely to be. To the left, an ancient farmhouse next to a modern one. In the background, the northern part of Rheneia and Tenos on the horizon. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades/D. Athanasoulis, Z. Papadopoulou, M. Sigala.

Western Cyclades

Kea

Karthaia

Karthaia is one of the four poleis of Kea, situated on the southeastern coast of the island and inhabited from the Early Iron Age to Late Antiquity (ID2071, ID2960, ID4218, ID5103, ID5053). The period 2002–2007 saw the completion of a large archaeological project, named ‘Conservation, Rehabilitation and Enhancement of Kea’s Monuments’, initiated by the Scientific Commission of the Resources Management Fund for Archaeological Projects (TDPEAE), funded by the European Union. As part of the project, the temples of Apollo and Athena(?) on the acropolis of Karthaia, including ‘Building D’, possibly of public character, were restored (Simantoni-Bournia et al. Reference Simantoni-Bournia, Zachos, Panagou, Koutsoumpou, Mpilis and Maurokordatou2006; Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou and Maurokordatou Reference Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou, Maurokordatou and Triantafyllidis2017b: 85–91).

A few years later, a second project succeeded into the full recovery, restoration, and study of the ancient theatre of Karthaia (2011–2015), as well as the configuration of the theatre’s wider area (Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou and Maurokordatou Reference Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou, Maurokordatou and Triantafyllidis2017b: 91–94) (Figs 8.6–8.7 ). The theatre is situated at the foot of the northwestern slope of the acropolis of Karthaia, close to the sea. Since its visible remains before the initiation of the project were few, a systematic excavation was conducted for five years, combined with a detailed documentation with photos and drawings.

8.6. Kea. Karthaia. View of the ancient city and the theatre (to the left). © E. Simantoni-Bournia.

8.7. Kea. Karthaia. View of the theatre. © E. Simantoni-Bournia.

Entirely built of local stone, the theatre of Karthaia is relatively small and modestly built, with an estimated capacity of 880 persons. It occupies an area of ca. 800m2 , in which the scene, the orchestra, and the koilon – composed of 15 rows of seats divided by three stairways into four kerkides (wedge-shaped seating sections) – were developed. The study of the finds from the excavation of the theatre places its construction in the middle of the fourth century BC (Simantoni-Bournia and Panagou Reference Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou, Zampas, Lambrinoudakis, Simantoni-Bournia and Ohnesorg2016; Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou and Maurokordatou Reference Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou and Maurokordatou2017a; Reference Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou, Maurokordatou and Triantafyllidis2017b: 94–98).

In 2009 and 2010, the excavation by the University of Athens, directed by Eva Simantoni-Bournia, concentrated on the northern edge of the Koulas plateau, dominating the site of Karthaia, where wall remains were visible. A structure of defensive character, triangular in plan, as well as a series of rooms south/southeast of it, came to light. These rooms represent part of a domestic complex in use during the Late Hellenistic period.

Agia Marina

The project, initiated in 2011, resulted in the consolidation and partial reconstruction of a Hellenistic tower at the site of Agia Marina in the western inland of Kea (ID2961, ID4219). Constructed in the fourth century BC, the tower has been incorporated into a 17th-century monastery, remaining in a good state of preservation until the middle of the 19th century, when parts of it collapsed (Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou and Maurokordatou Reference Simantoni-Bournia, Panagou, Maurokordatou and Triantafyllidis2017b). The monument was documented, studied, and protected by scaffolding.

The Kea Archaeological Research Survey

Within the framework of the Kea Archaeological Research Survey (KARS), a surface survey was conducted by Joanne Murphy, Amanda Kelly, and Shannon Hogue in northwest Kea (2012–2014), covering an area already examined in 1983–1984 (Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani Reference Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani1991). The aim of the project, conducted by the IIHSA in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades, was to explore the reliability of surface survey in order to assess if it has a lasting archaeological value, to perform macro- and microscopic analysis on the clay, metal, and stone artefacts, to study the island’s role in the trade networks and geopolitical landscape, and to reconstruct the landscape of Kea in antiquity (https://www.iihsa.ie/projects/the-kea-archaeological-research-survey-kars-project).

Although the area has already been surveyed, the results of the new project were very informative for the history of occupation and activity in northwestern Kea from the Neolithic era to the 19th century. The collected artefacts include mostly ceramics, stone tools, and waste from metallurgical production. Material from several Hellenistic towers in the area has shown the continuity of occupation of the sites since the Bronze Age, possibly due to their defensive character and agricultural potential.

Except for the information on the development of habitation in the Bronze Age in the area and its external contacts at the time, as illustrated on the ceramics, the collected black-glazed pottery suggests that this area was intensively used in the Late Classical and Hellenistic period, while most of the identified sites span from the Roman to the modern era. Beyond the connections with Attica, the finds illustrate the connectivity of the island with areas of the wider Aegean (https://www.iihsa.ie/projects/the-kea-archaeological-research-survey-kars-project).

Kythnos

Vryokastro

Excavations of the University of Thessaly in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades at the ancient city of Kythnos, today called Vryokastro, have been ongoing since 2002 (ID10101, ID9614, ID540, ID2049, ID2682, ID2983, ID4226, ID6187, ID6188, ID6614, ID8515, ID8158, ID18030). During the past 15 years or so, research has expanded to several areas of the Upper Town (2009–2013, 2016–2018, 2021–present) as well as on the islet Vryokastraki (2018–2020), which was once linked to the coast. This work was further complemented by the underwater excavation of the city’s ancient harbour, which was surveyed and excavated between 2005 and 2011 (a joint project between the EUA and the University of Thessaly: Mazarakis Ainian Reference Mazarakis Ainian and Triantafyllidis2018; Kourkoumelis, Mazarakis Ainian and Charalampidou Reference Kourkoumelis, Mazarakis Ainian and Charalampidouforthcoming).

Between 2009 and 2013, a two-storied public building of the Late Classical and Hellenistic period was excavated (Building 5) (Fig. 8.8 ). Access to the upper level was gained through a built staircase that led to a courtyard. The main room has a central hearth, beneath which several votive offerings were found, as well as official lead weights of the city. On the ground floor are two main rooms, one of which contained a rich deposit of finds: several could be regarded votive in character (figurines, jewellery), while others were of a more varied nature (medicine bottles, transport amphorae, etc.). The building may have been the Prytaneion of the Hellenistic city (Mazarakis Ainian Reference Mazarakis Ainian, Zampas, Lambrinoudakis, Simantoni-Bournia and Ohnesorg2016; Reference Mazarakis Ainian2019: 40–46).

8.8. Kythnos. Vryokastro. Aerial view of Building 5 (Prytaneion?). © A. Mazarakis Ainian/photo by C. Xenikakis.

In the south part of the so-called Middle Plateau of the Upper Town, intensive research between 2016 and 2018 led to the discovery of spectacular finds: here two adjacent monumental buildings of the Late Classical (Building 1) and Hellenistic (Building 2) periods were explored, as well as an ancient pear-shaped cistern incorporated at the southeast corner of the former edifice and a stepped propylon between the two edifices (Figs 8.9–8.10 ). Building 1 consists of two spacious rooms opening to a stoa of Doric order. The southern room was definitively a naos, since a free-standing stone base was found on the longitudinal axis, near the back wall. The northern room had a pebbled floor and a raised strip for the placement of couches, and could be identified either as a dining hall or an incubation hall. Indeed, the numerous finds – associated both with the edifice and also deriving from the attached cistern – have ascertained the identities of the divinities worshipped here: among the offerings one may note dedicatory inscriptions mentioning Asclepius and Aphrodite Syria, and marble statuettes depicting both divinities, as well as statues of naked boys and dressed girls. The nearby Building 2 was entered through the short sides, and access to four adjacent rooms of almost square shape was possible via a narrow corridor. The exact function of this building within the sanctuary remains to be clarified; one possibility is that it was an incubation hall associated with the Asclepieion (Mazarakis Ainian Reference Mazarakis Ainian, Vlachou and Gadolou2017b; Reference Mazarakis Ainian2019: 52–63; Reference Mazarakis Ainianforthcoming).

8.9. Kythnos. Vryokastro. Middle Plateau. Aerial view of Buildings 1 and 2. © A. Mazarakis Ainian/photo by C. Xenikakis.

8.10. Kythnos. Vryokastro. Middle Plateau. View of the ancient cistern attached to Building 1 during excavation. © A. Mazarakis Ainian.

On the summit of the acropolis, two areas are currently under exploration (2021–present). The southern part consists of rectangular rooms of uncertain date, which seem to relate to the military character of the fortified summit of the city. The northern part, clearly separated from the former part by a dividing wall, can be securely identified, both through inscribed dedications and the nature of the offerings, as a sanctuary of Demeter and Kore (Thesmophorion) (Fig. 8.11 ). The Archaic-Roman temple (‘Telesterion’), marked number ‘4’ in Fig. 8.11 , was excavated in 2021. It is a rectangular building facing west, with a main room and a back chamber (‘adyton’), containing numerous offerings, as well as Early Roman cups bearing graffiti with the names of women, offering them to Demeter and Kore, and numerous bones of piglets. The excavation of the possibly contemporary, elongated building (Fig. 8.11 , number ‘3’) to the south has just started, although it has already yielded numerous votives, mostly figurines of women and children, lamps of all kinds, including of the multi-nozzle type, and numerous bones of piglets, as well as other animals. In between Buildings 3 and 4, two small rectangular structures facing each other were excavated. These appear to represent additions of the Hellenistic–Roman period. The eastern edifice (number 5) yielded numerous offerings beneath its floor, while the interior of number 6 is divided into successive, decreasing floor levels, from east to west. The continuation of excavations in this area will allow a better understanding of the functioning through time of a Cycladic Thesmophorion (for preliminary research on the acropolis, see Mazarakis Ainian Reference Mazarakis Ainian2019: 47–51).

8.11. Kythnos. Vryokastro. Acropolis. Aerial view of the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore. © A. Mazarakis Ainian.

An ongoing three-year research project, Palimpsest: development of innovative technologies and methodologies for the promotion and protection of heritage sites (2021–2023), coordinated by the National Centre for Scientific Research Demokritos, also concerns Vryokastro. The analysis of numerous samples of finds from the excavations at this site will provide valuable information not only about the deterioration process of materials, but also with regard to the development of Vryokastro diachronically.

Lastly, between 2018 and 2022, research was conducted on the islet of Vryokastraki (Fig. 8.12 ) (ID8515, ID8158, ID18030). Fieldwork concentrated in three areas. The first, located at the south tip of the islet, revealed a monumental retaining wall and to its east an equally monumental altar hewn in the rock, associated with a sanctuary and in use from the Geometric to the Classical period. Unfortunately, the architectural layout of this important early sanctuary of Vryokastraki has been altered significantly due to Early Christian activities in the area and the construction of various edifices of the same era above the ruins of the earlier era. The second area of research focused on the monumental edifice following the east–southeast coastline of the islet. Here, 15 rectangular rooms were revealed, set along a spine wall that served also as a fortification wall facing the ancient harbour. The latest phase of this structure belongs to Late Antiquity, although there are indications that the original layout of the complex dates back to the Archaic period. Incorporated as spolia in the Late Antique walls, several ancient inscriptions were found, including an architectural regulation in the Doric dialect and a Hellenistic decree proving that the League of the Islanders was a creation of the Antigonids rather than of the Ptolemaioi. Lastly, roughly in the centre of the islet, an Early Christian three-aisled basilica was excavated. In the hieron area of the basilica, the encaenium (sacred foundation) was found in situ. This is the first such monument to be excavated on the island and marks the final period of use of the ancient capital, before its transfer to ‘Kastro’ stronghold at the northernmost abrupt coast of Kythnos (Mazarakis Ainian and Athanasoulis Reference Mazarakis Ainian, Athanasoulis and Gavalasforthcoming).

8.12. Kythnos. Vryokastraki. Aerial view of excavated edifices: Early Byzantine three-aisled basilica (Building 1), elongated Building 2, and Geometric-Classical sanctuary to the left. © A. Mazarakis Ainian/photo by C. Xenikakis.

Other sites on Kythnos

The rescue excavation at the site of Maïstralia in the southwestern coast of Kythnos brought to light the first rural establishment on the island (ID6680). A country house, built in the second half of the fourth or the first quarter of the third century BC, has been partly investigated. Six spaces surrounded a central courtyard, while remains of an olive or wine press were found. The destruction layer contained abundant plain pottery, as well as grinding stones and mortars.

At Agia Mariá (also known as Agia Marina) at the northeast of the island, an Archaic sanctuary was located and partly explored in 2015 and again in 2021–2022 by the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades. Architectural remains have been revealed, as well as offerings similar to those of the Archaic sanctuary at Vryokastro.

A survey operated on the northeastern part of the island – in an area delimited by Agia Irini to the north and by the hill of Profitis Ilias to the south, by the road leading from Ayia Irini to the island’s wind park to the west, and by the sea to the east – aimed at offering a more concrete picture of habitation in the countryside of Kythnos. In the northern part of the island, several ancient sites were also identified. In the hinterland above the area of Kolonna, along the Kakovolo ridge, a number of towers and rural settlements were noted. Remains of a rectangular building were found near an area with evidence of metallurgical activity. Surface pottery dates to the fourth/third centuries BC and the Roman era. Wall remains and Hellenistic pottery were found on the plateau on the top of the fortified hill of Kastraki. The presence of settlements has been concluded for the north part of the bay of Fykiada, as well as for the peninsula framing the bay from the east (Papangelopoulou Reference Papangelopoulou2012: 723–26 and 729).

A decade ago, some of the ancient towers of Kythnos were mapped and photographed. The rectangular tower at Ano Komi is today incorporated in an animal pen (keli) and the survey in its vicinity revealed remains of metallurgical activity. Part of a defensive structure has been incorporated into the foundation of an animal pen, situated at the beginning of a path leading to Mersinia, close to the site of Profitis Ilias. A round tower is located east of Mersinia and another near Kolonna, both preserving only part of their foundation. A round tower is found at Kolonna. The towers at Aspra Kelia and Aspra Spitia are located at sites where there were copper mines since the prehistoric era. Most of the towers are located at the northwest and northeast part of the island and they cover a chronological range from the middle of the fourth to the first quarter of the third century BC (Papangelopoulou Reference Papangelopoulou2012: 730).

The long-awaited archaeological museum of Kythnos, a project undertaken by the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades conjointly with the Prefecture of South Aegean, will be inaugurated early in 2023.

Siphnos

Agios Andreas

The 2015 excavation concentrated on the southwest part of the Geometric sanctuary at the site of Agios Andreas. Ten structures came to light, including a possible altar. The two construction phases of the peribolos wall have been confirmed through the exploration of the area southeast and outside it. Continued excavation of the sanctuary in 2020 brought to light new graffiti, possibly from the end of the Geometric period, as well as an enclosure, which surrounded a deposit containing offerings of the eighth and seventh centuries BC (ID17368). Two parallel curving walls of a possible apsidal building were found, in association with which a dagger, a pin, a bead, and Mycenaean and Geometric pottery came to light (for the sanctuary, see Televantou Reference Televantou and Mazarakis Ainian2017).

Seriphos

Part of the necropolis of the ancient polis was for the first time detected at the Bofiliou plot on the eastern part of the hill of the Chora in 2006. The continuation of the excavation in 2009 brought to light a number of adult inhumations in pit graves dating to the fourth and third centuries BC (Pantou Reference Pantou2009a: 882–83; ID5861).

In 2014 the project of formation and enhancement of Aspros Pyrgos was completed, undertaken by the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades (Fig. 8.13 ). This round tower is the best preserved on the island, acting as a point of reference for travellers since, at least, the 18th century. Made of marble in a particularly elaborate masonry, with a diameter of 8.34m and a preserved height of 4.95m, Aspros Pyrgos dominates over the southwest and west metalliferous part of Seriphos, located on the rocky ridge of the hill range, bordering the Koutalas bay from the northwest. It was built in the fourth century BC and remained in use until the seventh century AD. Its use was manifold, since it seems that it did not only have a defensive character, but it served as an outpost too. More importantly, its presence in this area, where there are indications of metal mining during the Late Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods, dictates that it must have acted as protection for these activities. The Ephorate’s project succeeded in documenting the tower’s form, its maintenance and protection, as well as the formation of the surrounding area for visitors (Pantou Reference Pantou2014a).

8.13. Seriphos. ‘White tower’. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades/P. Pantou.

The Archaeological Collection of Seriphos, which, since June 2022, is housed in the building of the Perseus guesthouse at Livadi, includes finds from Aspros Pyrgos as well as other parts of the island, such as a fourth-century grave stele possibly from Chora (Pantou Reference Pantou2014a: 2220–22).

Melos

The rescue excavations running at the site of Kouphi, at the northeastern part of the island, since 2009 brought to light four underground chambers as well as a rectangular, three-roomed edifice on top (ID5859). The destruction layer contained mainly pottery sherds of the sixth and fifth centuries BC. The excavation of the underground chambers revealed a large amount of mostly storage, cooking, and transport shapes, including numerous sherds of pithoi bearing relief decoration, dating from the seventh to the fourth centuries BC. The function of these structures remains unknown (Pantou Reference Pantou2009b; Reference Pantou2014b: 2007–14).

The Roman theatre in the ancient polis of Melos has been inserted into a programme of anastylosis, which resulted in the reconstruction of the lower part of the koilon, the orchestra, and the façade of the scene (2010–2015). The excavation of the scene revealed a succession of rooms covered by a vault in the lower levels. After the abandonment of the theatre in the fourth century AD, its premises continued to be used as residences or workshops until the end of the sixth/early seventh century AD.

Central Cyclades

Paros

Paroikia

The rescue excavations conducted by the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades, especially over the last 35 years, have offered valuable new data for the ancient capital of Paros, enlightening its borders as well as its domestic, funerary, cultic, and industrial spaces (Kourayos Reference Kourayos, Angliker and Tully2018a).

An open-air sanctuary has been detected west of the Delion of Paroikia, at the site of Marapas. Footprints densely carved on a small plateau have been interpreted as the pilgrims’ immortalized traces (Kourayos Reference Kourayos2015: 51–52; Reference Kourayos, Angliker and Tully2018a: 283–84).

Part of the south necropolis of the polis of Paroikia was explored at the modern site of Stavros, southeast of Paroikia. The rescue excavation brought to light a number of poorly furnished graves dating from the end of the fourth century BC to the Late Roman period, which seem to form part of an extended cemetery.

The premises of a marble sculpting workshop, where a sculpture school operated too, have been further excavated in 2008, 2010, and 2011. The workshop is located at the site of Floga, east of the modern peripheral road in Paroikia, ca. 160–180m west of the ancient wall (ID5824, ID6812, ID6692). An extended complex, comprising different buildings, has been investigated. Building A, occupying the southeast part of the excavated plot, probably housed textile production, before being abandoned by the end of the third or the early second century BC. A number of rooms (Δ1, Δ2, Δ3) at the southwestern part of the excavated area formed part of a marble sculpting workshop, which revealed a large amount of unfinished marble creations together with scrap marble. The industrial use of the site has been traced back to the Archaic era, but the workshop mainly operated in the late second/early first century BC. A large, carefully constructed building was found west of the workshop’s complex. Building B might have been of public use, most possibly related to the storage and promotion of the workshop’s products. The presence of pottery workshops and other industrial spaces in the immediate vicinity of the workshop suggests that they were part of an industrial area situated southeast of the polis within its fortification wall (Detoratou Reference Detoratou2012; Reference Detoratou2013).

Antiparos

Rescue excavations at Agia Kyriaki, at the east side of the island, brought to light remains of workshops producing three different types of wine amphorae in the Hellenistic period (ID2141). The discovery of amphora stamps with the ethnic ΠAPIΩN attests to the economic, and perhaps political, attachment of Antiparos to the neighbouring island of Paros.

The extent of vine cultivation on the island at least during the Late Classical period is further indicated by the detection of agricultural trenches at several sites on both Antiparos and Paros, including the site of Glypha close to Agia Kyriaki, as well as in the area of Agios Spyridon (Papadopoulou Reference Papadopoulou and Triantafyllidis2017).

Despotiko

The ongoing systematic excavation at the site of Mandra on the uninhabited islet of Despotiko, west of Antiparos, under the auspices of the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades has brought to light 26 buildings so far (Fig. 8.14 ) (for example, ID655, ID5825, ID1958, ID2329, ID3072, ID6693, ID4745, ID5227, ID6587, ID6594, ID8148, ID8509). The temenos of the Apollo sanctuary, discovered during the first years of the excavation, forms the nucleus of an establishment extending north, east, and south of it, as well as on the islet of Tsimintiri, which used to be connected to Despotiko through a narrow strip of land before being gradually separated by the rising sea level.

8.14. Despotiko. Aerial view of the temenos and surroundings. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades/Y. Kourayos.

Work at the site in the last decade has brought to light important evidence concerning the first period of the sanctuary’s activity, which can now be placed within the Early Iron Age. Two partly preserved buildings came to light under the Archaic temenos: the apsidal or oval Building O, built in the late ninth or early eighth century BC, and the rectangular Building Ξ that seems to have replaced Building O towards the end of the eighth century BC. A rich deposition, extending over the northern part of Building O, contained large quantities of Geometric pottery, mostly spanning the second half of the eighth century BC, a few terracotta animal figurines, more than 60 metal objects, and large quantities of animal bones that allow for the reconstruction of a domestic nucleus where cultic activities operated too (Kourayos Reference Kourayos2018b; Alexandridou Reference Alexandridou, Tsingarida and Lemos2019) (Fig. 8.15 ).

8.15. Despotiko. Plan of the Geometric and Early Archaic remains. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades/Y. Kourayos/plan by G. Orestides.

Occupation at the site continued into the seventh and early sixth century BC, as reflected by the recent discovery of other structures and buildings within, or in close distance to, the later Archaic temenos. These structures were either built over or abandoned later in the sixth/early fifth century BC. A large complex of buildings was explored east of the temenos of Apollo. Although some of them operated in the sixth century, others date later, throwing light on the activities at the site in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. The expansion of the excavation on Tsimintiri, since 2020, resulted in the discovery of eight buildings of large dimensions along the eastern part of the harbour, which could control the passage through the ancient isthmus. Founded most possibly in the Archaic era, they are much larger than those of Mandra, possibly indicating public structures (Fig. 8.16 ).

8.16. Tsimintiri islet. Aerial view of the architectural remains. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades/Y. Kourayos.

The topography of Mandra has been further enriched since 2020 after the discovery and exploration of a complex and extended system of cisterns a few metres south of the temenos. The main cistern is 3.8m deep with internal dimensions 7.5 × 5.5m. The main period of its use should be dated to the Archaic and Classical period, although evidence suggests that it was also used in Byzantine times. Water was collected in a round cistern with a diameter of 11m, from which a built channel 25m long leads to two rectangular cisterns. These cisterns must have been for filtering the water before being collected in the main deep cistern.

After numerous seasons of fieldwork, 2021 marked the completion of the demanding restoration project aimed at the enhancement of Building A, composed of the ‘temple’ and the hestiatorion (dining hall) (Fig. 8.17 ). Following exhaustive archaeological and architectural documentation, the restoration was largely based on the interpretation of the archaeological data in combination with the pertinent architectural comparanda, depending on the number and placement of the surviving building blocks. The two components of Building A, the heart of the temenos of Apollo, were treated as a single comprehensible complex, since the restoration project had an aesthetic, protective, and deeply educational purpose (Kourayos et al. Reference Kourayos, Daifa, Orestidis, Egglezos, Papavasileiou, Toumbakari, Sapirstein and Scahill2020).

8.17. Despotiko. Temenos area. View of the temple and hestiatorion after restoration. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades/Y. Kourayos.

Naxos

Chora: Plithos and Aplomata

Part of the north necropolis of the Chora of Naxos came to light below architectural remains of the Late Antiquity during two rescue excavations at the sites of Plithos and Aplomata. More than 50 graves were explored at Plithos, including a few adult inhumations, numerous enchytrismoi, and cremations protected by enclosures (ID5544). An area used for the cremation of the dead was detected at the centre of the excavated plot. The cremains were placed either in pits or inside large pithoi, amphorae, and hydriai. The graves revealed more than 200 vases from the Protogeometric to the end of the Geometric period. Except for pottery, the graves also yielded a few gold and silver pieces of jewellery, bronze and bone objects, clay textile production implements, and seashells. Three inhumations in pit graves furnished with vases and six enchytrismoi were detected at Aplomata (Legaki and Mavroeidopoulos Reference Legaki, Mavroeidopoulos and Triantafyllidis2017: 387–91; ID6814).

Chora: Bourgos

A rescue excavation at the site of Bourgos in the Chora brought to light subsequent levels of occupation, extending chronologically from the Early Iron Age to the post-Byzantine era. Architectural remains and floors have been dated to the post-Byzantine, Roman, Hellenistic, Classical, and Geometric periods. Part of a Roman house, well, and water tube were detected, below which Mycenaean pottery came to light (Papangelopoulou Reference Papangelopoulou2013: 756; ID6691).

Southeast Naxos survey

A new four-year project, including an archaeological survey of southeast Naxos, was initiated by the BSA and the University of Cambridge, directed by Colin Renfrew and Michael Boyd (2015–2018; ID5567). The entire coastline from Volakas at the east to Kalandos at the west was covered. On the basis of the preliminary study of the collected ceramics, southeast Naxos was more densely populated in the later Early Bronze Age and again in the Hellenistic and later periods, with evidence of occupation for the Archaic and Classical periods too. Two Hellenistic towers were recorded.

Underwater Archaeological Survey, southern Naxos

The three-year Underwater Archaeological Survey (2016–2018) in the sea off southern Naxos undertaken by EUA, NIA, and the Norwegian Maritime Museum in Oslo aimed particularly at locating and documenting the ancient and Byzantine harbours, anchorages, and wrecks along the island’s southern coastline, from Alykos to Panormos (https://www.uib.no/en/nia/135143/completed-projects#S%20Naxos%20underwater). The function and the period of use of these natural harbours, as well as their relationship with specific settlements during particular time spans, were put under the microscope. Two harbours or anchorages have been surveyed (Panormos, Kastro Apalirou). Five stone anchors, amphora fragments of the Late Classical period, and pottery of the Classical period were found in the bay of Agios Sozos, southeast of Cap de Moni, confirming the use of this natural harbour as an anchorage from the Archaic to the Byzantine era.

Irakleia

The Irakleia Caves Exploration Project, a cooperation of the Ephorate of Palaeoanthropology and Speleology together with NIA (2014–2016), aimed at the systematic investigation of the caves on the island of Irakleia of the Lesser Cyclades, located south of Naxos (Mavridis, Tankosić and Kotsonas Reference Mavridis, Tankosić, Kotsonas, Angliker and Tully2018). The systematic excavation of the Agios Ioannis/Cyclops Cave complex at the southwest part of the island led to a number of conclusions. The preliminary study of the material from these caves provides a unique picture of a site with continuous use from the Neolithic to the Roman and later periods. Research at Irakleia confirms that caves were important throughout the Bronze Age, but also during later periods. The wider aim of the project is to allow for a better understanding of the caves in the Central Aegean due to their importance for both every day and religious life (Mavridis, Tankosić and Kotsonas Reference Mavridis, Tankosić, Kotsonas, Angliker and Tully2018).

Pholegandros

A note should also be made here for the recent research concerning the Chrysospilia Cave on the northeastern side of Pholegandros, on the slope of Paleokastro, where the ancient city was located (for earlier reports: ID14167, ID11495). The uniqueness of this cave lies in the large number of painted inscriptions of mostly male names, covering all its side walls, written in a clayish mixture of light or dark brown. The sample analysis by X-ray fluorescence at the Laboratory of the Demokritos National Research Centre showed that this ‘paint’ is composed of iron oxides and some soil, originating from the island. The inscriptions reveal the use of the cave for some ceremony of adolescent initiation, attracting young males from all over the Aegean and the eastern Mediterranean too (Vassilopoulou Reference Vassilopoulou, Angliker and Tully2018).

Island-wide projects

Over the last years, a number of large research projects have focused on the Cyclades. A large-scale project, running since 2019, is The Small Cycladic Island Project (SCIP) – a collaboration between the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades, NIA, and Carleton College (ID17974, ID17975). It aims to document human activity on the small islets in the Cyclades forming a particular ecosystem. In 2019 and 2020, 21 small islands around Paros and Antiparos were systematically surveyed with the use of various multi-disciplinary techniques (Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis, Tankosić, Cherry, Garonis, Levine, Nenova and Öztürk2020; Athanasoulis et al. Reference Athanasoulis, Knodell, Tankosić, Papadopoulou, Sigala, Diamanti, Kourayos and Papadimitriou2021). In 2021, the project expanded to the islets around Kythnos (Agios Loukas, Agios Ioannis Eleimon, Zogaki, Kalo Livadi, and Piperi), Seriphos (Seriphopoula and Vous), Siphnos (Kitriani), and Syros (Didimi, Strongylo, Aspro, Schoinonisi, Strongylo, Diakoftis, Psathonisi, Alatonisi, Delfini, and Varvarousa). In 2022 work focused on the islets around Melos and Kimolos (Fig. 8.18 ).

8.18. Map of the small islands surveyed within the 2019–2023 Small Cycladic Islands Project. © SCIP/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades/NIA/Carleton College/A. Knodell.

Widespread activity was noted across many islets in the Archaic and Classical periods, including both habitation (such as a Geometric to Early Classical, and mostly Archaic, settlement site at Filizi: Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis, Tankosić, Cherry, Garonis, Levine, Nenova and Öztürk2020) and specialized activities (such as quarrying on Tigani and Dryonisi: Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis, Tankosić, Cherry, Garonis, Levine, Nenova and Öztürk2020). Three Hellenistic towers were identified on Strongylo (Athanasoulis et al. Reference Athanasoulis, Knodell, Tankosić, Papadopoulou, Sigala, Diamanti, Kourayos and Papadimitriou2021), Seriphopoula, and Piperi (Knodell, Athanasoulis and Tankosić Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis and Tankosić2022).

The survey of Polyaigos in 2022, the largest uninhabited island in the Aegean, provides an opportunity within the comparative framework of a single project to examine size as a key factor in occupational history (pers. comm. with Alex Knodell). Ongoing research has shown that these small islands represented a particular type of micro-environment occupied for certain periods and supporting a range of human activity. Although marginal, they formed part of wider systems, being in close contact with larger islands.

Finally, Siphnos, Seriphos, and Kythnos, as well as the community of Asgata in Cyprus, were inserted into the project Metal Places: Culture Crossroads in Eastern Mediterranean, undertaken by the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades in collaboration with the National Centre for Scientific Research Demokritos, the Municipality of Siphnos, the Archaeological Research Unit of the University of Cyprus, and the Community of Asgata. These Cycladic islands and the Cypriot site preserved abundant metallurgical remains and rich evidence of ancient mining. The main aim of the project is the promotion of the selected areas for touristic purposes with the use of modern technology, underlining the common cultural elements shared by Greece and Cyprus.

Some concluding thoughts

The archaeological work conducted at the Cycladic archipelago during the last decade is extensive and reveals the importance of the islands for the archaeology of Greece during the historical period. The excavations and surveys on the various islands allowed important insights into various aspects of life in antiquity. Settlements, burial sites, and cult areas were explored or studied, while workshop activities were also documented. Moreover, the conducted underwater surveys and excavations threw light on the islands’ harbours, elucidating the existing trading networks and the development of their connectivity.

The last decade marked the increased interest from the side of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, through the Ephorate of the Antiquities of the Cyclades, for the protection, restoration and enhancement of archaeological sites and monuments. This activity underlines the concerted effort for the promotion of the cultural heritage of the islands.

The overview of the archaeological activity in the Cyclades during the last years revealed some imbalances. The systematic excavations conducted on the islands remain few (Andros, Tenos, Kythnos, Delos, Rheneia, Despotiko), complemented by a number of land and underwater surveys. More importantly, although the number of the rescue excavations has risen in most of the islands due to the intense construction activity, relevant information is not found. Unfortunately, many islands are escaping the present report (e.g. Mykonos, Kimolos, Thera, Anaphe, Amorgos).

The Cyclades will continue to attract archaeological interest, as is well reflected in the numerous projects run particularly by foreign archaeological schools in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades. Since the islands have become major tourist destinations for both Greek and foreign visitors, it is important for the sites and the monuments on them to be protected, conserved, and become accessible, while acquiring an active presence in the life of both modern islanders and visitors. The restoration work of the Roman mausoleum of the second–third century AD at the site of Episkopi on Sikinos brought to light the rich burial of a woman named Neikó (Nεικώ) (https://www.culture.gov.gr/el/Information/SitePages/view.aspx?nID=2310). The mausoleum was later transformed into a Christian church. This restoration project was awarded the Europa Nostra Prize in 2022, which promotes best practices in heritage in Europe (https://www.europeanheritageawards.eu/winners/monument-of-episkopi/) (Athanasoulis Reference Athanasoulisforthcoming). This is an outstanding example of such an effort undertaken by the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades (Fig. 8.19 ). The work at Episkopi allowed for the correct identification of the monument – interpreted in the past as a temple of Apollo Pythios (Frantz, Thompson and Travlos Reference Frantz, Thompson and Travlos1969) – and the reconstruction of its history.

8.19. The monument at Episkopi on Sikinos. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades/D. Athanasoulis.

Except for the completion of the currently ongoing projects, the coming years will ideally see the initiation of more systematic excavations on the islands, especially those not intensively explored so far, as well as the publication of the results of surveys, excavations, and various other projects. This activity will undoubtedly promote further research on Cycladic archaeology of the historical periods.