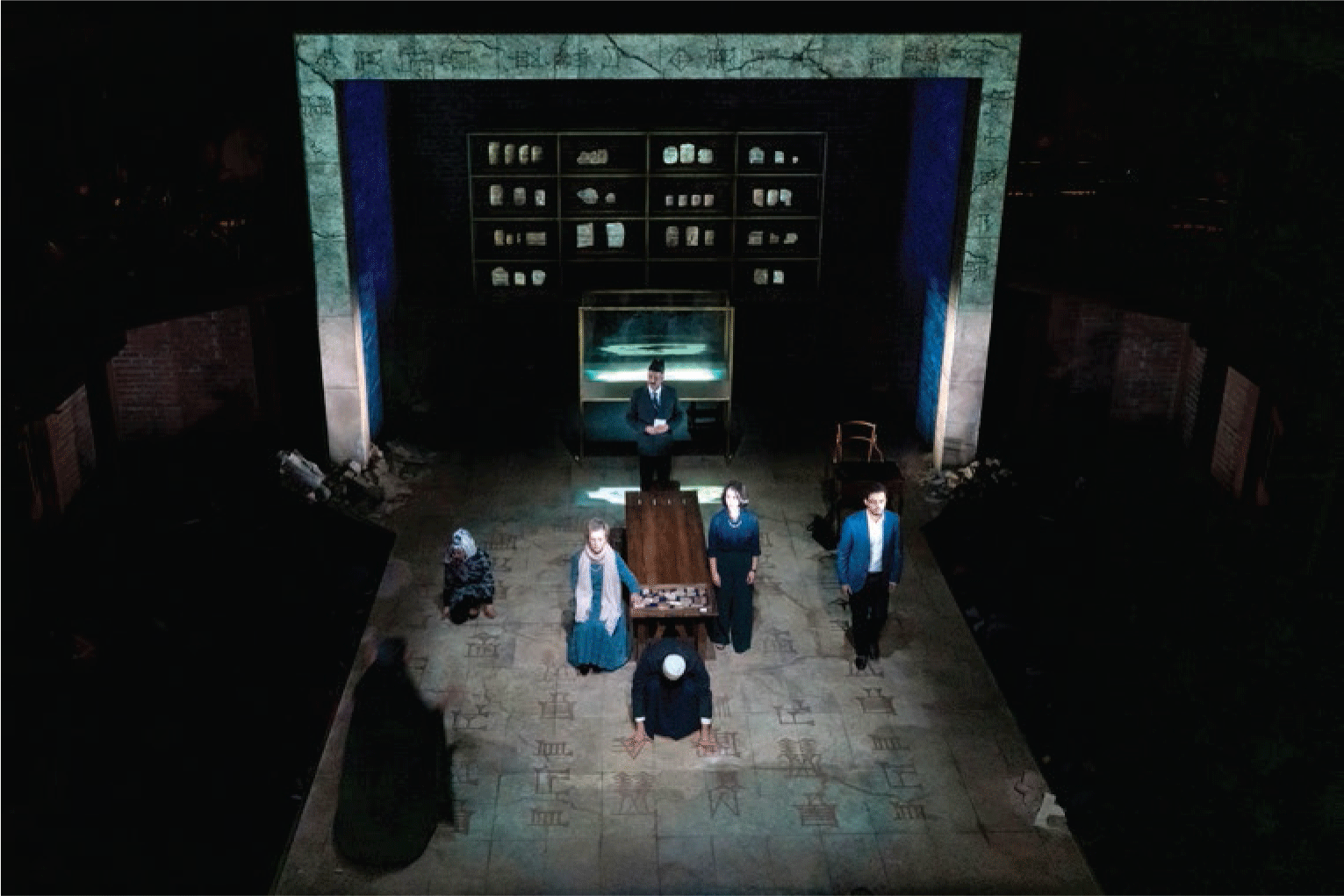

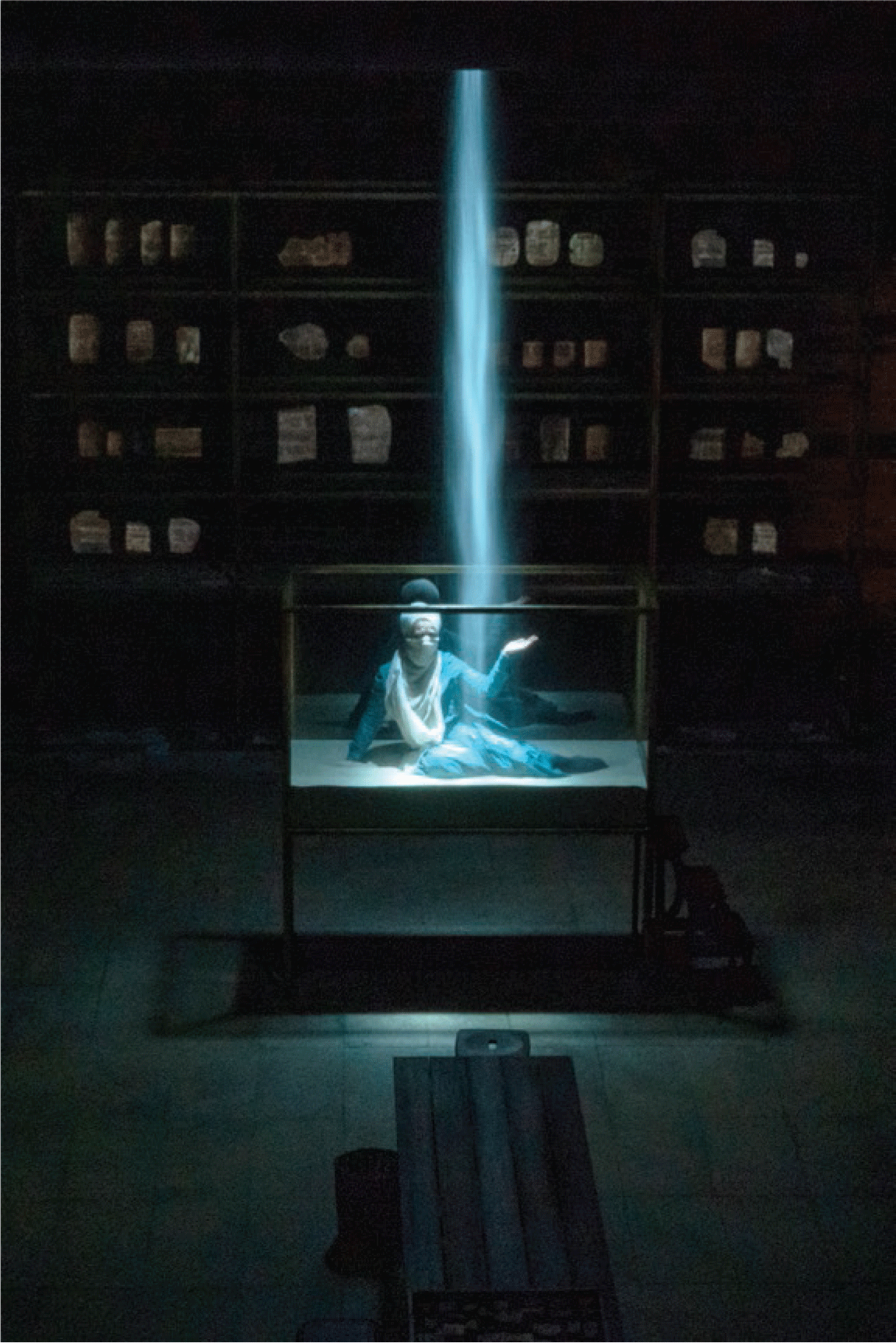

Figure 1. Gertrude (Emma Fielding) seated in the glass display case with museum artifacts on the display shelves projected onto the backwall. A Museum in Baghdad, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

[Our] cultural treasures […] owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great geniuses who created them, but also to the anonymous toil of others who lived in the same period. And just as a document is never free of barbarism, so barbarism taints the manner in which it was transmitted from one hand to another.

—Walter Benjamin ([1940] 2003:392)Always there lurks the assumption that although the Western consumer belongs to a numerical minority, he is entitled either to own or to expend (or both) the majority of the world’s resources.

—Edward Reference SaidSaid ([1978] 1994:108)Mapping a Country into Being

An Irreversible Trip to the Pits

It all began (again) with two men having a clandestine meeting in a quaint café corner in London in 1916, not to discuss interregnum avantgarde trends in London and Paris, but to carve out new countries and territories. They were set to partition a vast unmapped and undemarcated geographical expanse left in the wake of a vanquished Ottoman Empire; a territory which later constituted a part of what came to be called the Middle East (see Berdine Reference Berdine2018; Lukitz Reference Lukitz2006). The two men were Mark Sykes and George Picot, diplomats representing the British Empire and France respectively, and they established the premise of a secret treaty between the two countries with a nod from the Kingdom of Italy and the Russian Empire. The agreement since its implementation came to be known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement (see Lieshout Reference Lieshout2016). Thus was Iraq established as a nation and country—along with three others: Syria, Lebanon, and southeastern Turkey, which (along with northern Iraq) were all in the French sphere of control; Palestine, the rest of Iraq, Jordan, Haifa, and Acre were in the British sphere of control.

Gertrude Bell was officially tasked by the British government to cement British hegemony and the smooth implementation of the Sykes-Picot Agreement at a local-national level—among native Arabs and Kurds. Notably, however, Sykes and Bell were fierce rivals. This is evidenced by Sykes’s hostile description of Bell as “a flat-chested, rump-wagging man-woman—a blethering windbag” (in Lukitz Reference Lukitz2006:3). The other significant difference between Bell and her two senior colleagues, Sykes and Arnold Wilson, involved their drastically divergent views on the dynamics of the relationship between the Arab local government and the British Empire along with their attitudes toward Arabs as a people (see Naiden Reference Naiden2007).

In 1911, Bell joined British forces as a representative in the Arab world where she worked in various places including Palestine, Syria, Egypt, and Iraq. While her personal interests in archaeology and culture ran parallel with the extensive political enterprises and activities of the British government in the region, she worked on behalf of the government first under Wilson and later under Percy Cox. Variously referred to as an “arch-imperialist” (Melman Reference Melman1995:5), “the uncrowned Queen of Iraq” and a “spy” (Wallach [Reference Wallach1996] 2005:324, 145), Bell played a prominent role in bringing Faisal I of Iraq to power as the king of Iraq, acted as a determining force (along with T.E. Lawrence) in rallying local Arabs to fight and oust the Ottoman Empire, and promoted Britain’s hegemony in that region. Both Bell and Lawrence harbored profound admiration for native Arab and pre-Arab culture, language, and history and promoted the political transition from British imperial rule to Arab rule of Iraq and other Arab territories.

In the misogynist judgment of her male colleagues, Bell was described as “changing her directions each time as a weathercock” (Wallach [Reference Wallach1996] 2005:3), while in fact she proved staunchly committed to the cause of consolidating Iraq as a nation and culture. She contributed considerably to the establishment of the Baghdad Archaeological Museum, now the Iraq Museum, and dedicated herself to preserving the country’s heritage. In 1922, Bell was appointed the director of antiquities by King Faisal and fought on numerous fronts to keep important artifacts in Iraq. This is attested by her notable role in the crafting of the 1922 Law of Excavation (Gibson Reference Gibson and Peter2008:33). In 1923, as her political role diminished, Bell began working on her plans for the museum to serve as a sanctuary for Iraqi artifacts and antiquities. Her efforts culminated in a crowning achievement: the inauguration of the museum with the opening of its first exhibition space on 16 June 1926 with King Faisal attending the ceremony. During her last years, particularly between 1922 and 1926, Bell withdrew from public life. Her social circles and links shrank, she suffered emotional loss, and her political activities diminished. She found herself among new British officers and agents whom she hardly knew personally. She spent the final months of her life working on the museum, cataloguing items found at two ancient Sumerian cities, Ur and Kish. Bell died on 12 July 1926 from an overdose of sleeping pills, with no determination if it was an accidental overdose or suicide (see Amoia and Knapp 2005:esp. 156).

The neat, chronological account above, concerning both the imperial-colonial constitution of Iraq as a nation-state and Bell’s formative role in the establishment of both the country and its first national museum, is exactly what Hannah Khalil’s A Museum in Baghdad (2019) does not offer. Rather than a chronological, historicist account of the emergence of Iraq as a nation in conjunction with the history of various modes of violence inflicted on it at various levels—its natural resources, its politics, and its sociocultural life—A Museum in Baghdad confronts us with a manifold, fluid temporal structure where past, present, and future are inextricably entangled. As the stage directions indicate: “We are in the Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. […] We are Then (1926), Now (2006) and Later (this could be in 50, 100 or 1,000 years into the future)” (Khalil Reference Khalil2019a:3).Footnote 1 These three historical folds and temporal layers, far from remaining distinct, prove to have structural implications and imbrications. While the 1926 (or the “then”) fold depicts the nearly simultaneous constitution of Iraq as a nation-state and of the Museum of Iraq as the national museum, the 2006 fold hurls us into the infernal chaos emerging in the aftermath of the US-led invasion of Iraq—the ousting of Saddam Hussein under the guise of establishing an American-style democracy. A Museum in Baghdad is a nonnaturalistic play in which the colonial-imperial genealogy of the contemporary woeful condition of Iraq in conjunction with the cyclical dynamics of such a history within a petro-capitalist global system are thrown into relief (see Fakhrkonandeh Reference Fakhrkonandeh2023). In the 1926 fold we see Gertrude, Professor Woolley (a British archaeologist and Gertrude’s senior archaeologist colleague), and Salim (Gertrude’s Iraqi assistant). In the 2006 fold we encounter Ghalia, an Iraqi-born woman and British citizen by marriage who has been living in the UK for many years and who occupies the same position Bell held, the head of the museum; Layla, who occupies Salim’s role and whose postcolonial consciousness and nationalist stances are far more sophisticated and prescient than her 1926 counterpart; and Mohammed, one of the museum assistants and Layla’s fiancé. Above all, there is Abu Zaman (which in Arabic literally means “the father of time”), who is a transhistorical character in the play—“a character who straddles time and space, trying to affect the future”—through whom the three historical periods (or temporal folds) intersect: Then, Now, and Future. Abu Zaman is also the visionary character who can presage future events, leaving him brooding and haunted by the gloom of imminent catastrophe.

A Museum in Baghdad, co-commissioned by the Royal Lyceum Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company and premiered at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, in January 2019, is set in the museum. In their palimpsestic assemblage of world-oriented and mnemonic objects, highly invested in histories and prehistories, museums offer semiotically, ontologically, and historically rich and rewarding sites of inquiry and intervention for theatre and drama. And it is in a museum that the thematic crux of the actions, the personalities of its characters, the conflicts among historical forces, and the intersection between various historical layers transpire and unfold. As a site where time is spatialized and space is temporalized, the Baghdad Museum in the play features as an overdetermined metonymy: on the one hand it represents the Iraqi nation and its diverse cultural layers; on the other, it illustrates how museums (as a synecdochic part of the imperial machinery) function as the institutional-discursive apparatus facilitating the extractive operations of imperial force and ideology.

A Museum in Baghdad, in its juxtaposition of 1926 and 2006 shot through with an indefinite future, probes the ravages of colonialism and imperialism at personal, national, and global levels. As a decolonial critique, what distinguishes the aesthetics of the play is its historical method, which is characterized by two features: first, its adoption of an antihistoricist, or antihistoriographical, approach; and second, its conception of historical time in terms of “longue durée” (see Braudel Reference Braudel, Wallerstein and Richard2012). Into this elaborate aesthetic and historical structure, Khalil weaves allegory and evental realism (or irrealism). The latter are terms I utilize to characterize the distinctive ways in which time (including myth, history, and the relational dynamics between the two), space, and world (ontology) are treated in A Museum in Baghdad.Footnote 2 As a consequence, not only does A Museum in Baghdad draw parallels between the two critical junctures in Iraq’s long history of extractivist exploitation, originary displacement, and ideological/imperial alienation; it also adds a “mythic,” or prehistorical (hence immemorial), past fold—an addition that, coupled with the “indefinite” future fold of the play, not only extends the temporal span of the play into an indefinite past, but also compounds its temporal structure beyond a simply linear or cyclical dynamics, thereby opening up space for the dimension of the evental. A Museum in Baghdad thus establishes causal, genealogical, and gendered political-economic links between these vastly separate historical periods and practices by situating them in the longue durée of imperial capitalism and phallogocentrism. In so doing, A Museum in Baghdad not only throws into relief the systemic and cyclical manner in which subaltern subjects (local Iraqis, especially women) and peripheral countries (Iraq) have similarly been exploited as a source for cheap resources, cheap labor, and a geopolitically strategic ground. It also opens up a space for the emergence of the immemorial—the erased or repressed memories of disastrous traumas; and the evental—a future not determined by the structures of the imperial-phallogocentric history.

A Museum in Baghdad presents a compelling retrospective critique of the colonial operations of Khalil’s imperial homeland (Britain) in Iraq and evinces commitment to the exposure of systemic political-economic links between the cultural institutes of the colony (the Iraq Museum) and metropole (the British Museum). Equally importantly, A Museum in Baghdad reveals how such colonial-imperial operations are informed by a core-periphery logic of extraction and a dynamics of combined and uneven development (see Trotsky [1930] 1977:26–27; Shapiro and Lazarus Reference Shapiro and Lazarus2018:1–36) where the cultural institutes (such as the Iraq Museum) were utilized as a camouflaged conduit for the imperial extraction and transference of the artifacts/treasures to a “safer” home (the British Museum). A Museum in Baghdad, however, should not be perceived as instantiating a singular interest in the history of Iraq. The play, in fact, features as one emblematic link in the extended body of Khalil’s work, which is preoccupied with the broader geography and long history of the Arab world and its political and cultural vicissitudes. A sweeping survey of Khalil’s work demonstrates how her concern with the history, genealogy, and geopolitics of the Arab world extends far beyond Iraq to encompass Palestine, Syria, and more broadly the Middle East as an assemblage of indelibly braided cultures and histories. Her contribution of two plays to the volumes of dramatic works specifically concerned with the ramifications of the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the formation of the Middle East are emblematic cases in point (see Pickering 2015).

When asked how aware of the stereotypical representations of Arab culture and Middle Eastern heritage she is, Khalil responds: “Very, very, very—trying to redress the balance of the way Arabs are portrayed on stage and screen is one of the reasons I started writing in the first place. I have always considered representations of Arabs and Muslims to be completely stereotypical and narrow” (in RSC 2021). However, concerning European colonialism in Iraq, she also refuses to unilaterally condemn the actions of the colonial powers: “It’s easy to see colonialism in very black and white terms but the truth is the European colonial influence on the world is a myriad of greys. Without it […] I wouldn’t exist! […] Ultimately it feels to me like even if some of the individuals involved in colonial projects had good intentions, the overall aim was for Europe to benefit from those colonized countries’ assets” (in RSC 2021). By accentuating the aporias of colonialism at the level of individual lived experiences, Khalil offers her perception of colonialism from a phenomenological-existential perspective. Correspondingly, what distinguishes Khalil’s take on Iraq’s history is her refusal to naively glorify it and flatly condemn Western imperialism.

Some of the recurring preoccupations of Khalil’s work are the questions of Palestine, (neo)colonial and imperial violence, cosmopolitanism and hybridity, (de)colonization, and the precarious life of refugees. Her most prominent works include: Plan D (2010), Bitterenders (2010), The Worst Cook in the West Bank (2014), The Scar Test (2015), Scenes from 68* Years (2016), A Museum in Baghdad (2019), and Censor (2020). She is a prolific dramatist and her work has been produced by major theatre companies, yet scant critical attention has been paid to her work by scholars. This article is thus the first to undertake a sustained and extended analysis of Khalil’s work generally and A Museum in Baghdad in particular.

Along with the manifold issues of time and history, the crux of A Museum in Baghdad is the implicit parallel between the two concomitant processes of museum-building and nation-making; the former constitutes the foreground and the latter the hinterland of the play. Hence in the play, (neo)colonial and decolonial forces coexist in tandem and tension. The museum, along with the characters of Abu Zaman and Gertrude (based on Bell), is a ballast between the two historical periods and an indefinite future plane, thereby providing spatial continuity in the temporal flux of the play. Khalil invokes museum(-making) as a metonym not only for the dynamics of colonial-imperial resource extraction/exploitation and establishing social-cultural hegemony, but also for the process of nation-building. The manifold issues of time and space are indelibly intertwined and play a pivotal role in both the thematics of the play and its political-historical and ontological dynamics, which I address here.

Irrealism and Its Aesthetic, Ethical, and Social-Historical Implications

A Museum in Baghdad confronts us with the image of a “broken hourglass”—an image that is my metaphorical description of the play’s irrealist treatment of time: a nonlinear/nonrealistic rendition of various historical layers along with anachronisms and moments of evental near-synchrony. There is a profuse presence of sand throughout the play, including in a glass display case: Towards the end of the play Gertrude is shown to be inside the case and is incrementally buried as sand pours down from above the stage, as if into the lower half of an hourglass. The cabinet is a showcase in the museum, presented in the play as a glass case that is continually filled to overflowing with sand, one of the functions of which is to serve as a medium for and a visual representation of the intersection of the narrative’s two main folds. Throughout the play, there is a cumulative influx of sand into the museum space—ostensibly blown in from the desert lands outside the museum. The female American soldier York who is the security guard in the museum keeps sweeping the insidiously cumulative sand, to no avail. And finally, there are references to archaeological discoveries unearthed by floods that have washed away monumentally sedimented sands of history to expose buried (pre)historical moments. Once out of the glossy constraints of the hourglass, sand grains cease to be dead objects—a means of measurement. Instead, they assume a life of their own as agential subjects.

As indicated above, A Museum in Baghdad comprises three intertwined and intersecting temporal-historical folds. The 1926 fold depicts Gertrude in her attempt to prepare the Baghdad Museum for its opening with the help of her Iraqi assistant Salim and Abu Zaman. Gertrude is also trying to protect the museum’s artifacts from Professor Leonard Woolley, another British archaeologist who wants to transfer them to the British Museum in London. The 2006 fold presents Ghalia Hussein, a British archaeologist of Iraqi origin who is preparing to reopen the museum after it was looted during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. She is assisted by Layla (an Iraqi archaeologist), Mohammed (an Iraqi curator), and York (an American soldier assigned to protect the museum). The reopening proves a failure because of Nasiya, an Arab woman who protests the opening by sabotaging one of the valuable artifacts on display. The future fold of the play is seen through Abu Zaman’s visions of the future, through a glass cabinet (a kind of hourglass, too), in which the Baghdad Museum is raided by masked men who abduct and execute an older Mohammed, who is the director of the museum in the future fold. This recurring scene where Mohammed is grabbed with his head wrapped in a pillow and “hustle[d…] out of space” (7) is either preceded or ensued by Abu Zaman’s act of coin-tossing or going “behind the glass cabinet and look[ing] through it as though it is a crystal ball” (7) or his utterance (“It’s time” [3, 91]).

Such a dynamic adumbrates the recurrence of cycles of invasion, dispossession, and violence into the future. True to the transversal dynamics of the play, the action, in all three folds, is intermittently punctuated by an eruption of poetic reflections delivered in the form of “choruses” either as soliloquy or dialogue. In these choral reflections—which act as contrapuntal voices and visions—one (often Abu Zaman) or more characters suddenly comment in a mixture of Arabic and English on the action as if from a different (even transcendental) temporal plane/perspective.

Figure 2. The broken hourglass of A Museum in Baghdad, with Emma Fielding as Gertrude recumbent as sand pours down from above. The Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

There are discernible correlations between the Then and Now planes of the play intended to accentuate both overlaps and differences between the two (neo)colonial histories. These include similar events in different time periods unfolding simultaneously on the stage from the beginning:

(The space is filled with dignitaries and perhaps the odd soldier from Then, Now, and Later.

There are three ribbons, three pairs of scissors, three important people.

Each important person cuts their ribbon.)

IMPORTANT PEOPLE: I officially open this museum.

ABU ZAMAN: (With a chorus made up of Nasiya, Ghalia, Layla) Again مرة اخری. (3)

Figure 3. The display shelves of a museum projected onto the back wall evoke the main setting of the play: the Baghdad Museum. A Museum in Baghdad, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

Parallelism and intersection between the two temporal layers are further accentuated through the use of identical phrasing and/or overlapping speeches from different temporal folds. Two notable instances are when Gertrude and Ghalia happen to have identical speeches: On one occasion we read: “Gertrude/Ghalia: I prefer to be amongst the artefacts—that’s why I’m here”; and on another: “Gertrude/Ghalia: Thank God she’s not damaged. (Indicating the invisible statue.) So beautiful” (23, 24). There are also numerous moments when both Gertrude and Hussein say identical lines. In the premiere production, which I viewed on a recording shared by the RSC, the words of the chorus are split up and thrown around by all those onstage—manifested by the freezes and mime sequences.

This parallelism/intersection is evident when characters from different temporal folds perceive the same objects across time: “The three exit leaving the crown behind them. GERTRUDE steps forward and picks it up. GERTRUDE, LAYLA and YORK all look at it” (41). In the play’s debut production—with Erica Whyman as the director and David Greig and Pippa Hill as dramaturgs—the stage was designed to underscore the above parallelisms/intersections: the space and props—two empty display cabinets, shelves, and desks—were shared by characters from different temporal folds. Furthermore, in choral reflections throughout the play, characters from both time periods join Abu Zaman and comment on events in the playFootnote 3: “ABU ZAMAN: (with chorus of Ghalia) Safer? اکثر اماناً” (5-6) or “ABU ZAMAN: (with Nasiya who speaks in Arabic) You’d have to live forever یحب ان تعیش الی الابد” (21). The choice of characters that pair with Abu Zaman seems far from random. In fact, such choral moments not only afford us a glimpse into the personalities of those characters, but provide us with analeptic commentaries and proleptic insights. When the word “safety” is uttered, it is Ghalia (and nobody else) who joins Abu Zaman in the chorus. As the play progresses, Ghalia transpires as a person concerned about her safety and ends up leaving Iraq for that reason. Correlatively, the reason why it is Nasiya who joins Abu Zaman in the above choral reflection is that Nasiya is a “timeless” character too.

Figure 4. Characters from both temporal folds stand together as a choral unit with the ancient crown on display center stage. A Museum in Baghdad, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

However, it is not these juxtapositions of time periods that render A Museum in Baghdad a work of irrealism or evental realism, but the nature and dynamics of Abu Zaman’s role and his power to affect/change the future by tossing a coin. Put succinctly, “irrealism” designates the instances or manifestation of the disruption, anamorphosis, and subversion of forms and the subversion of the (linear and realistic) logics of narrative, time, and space registered at formal (narrative form and language) and psychological (character) levels. The irrealism of form is intended to act as a potent and revealing registration of the destruction and distortion of the local-national realities of history, geography, and demography as lived by the native people in “peripheral” countries (predominantly the Global South) wrought and exerted by the forces of colonial and imperial petro-capitalism and globalization. As Michael Niblett explains: “If irrealism comes to the fore in those periods when ‘all that is solid melts into air,’” we might assume that it would “wane as an aesthetic strategy once the emergent conditions have been stabilized and new socio-ecological unities created” (2012:23). We can thus infer that the violence exerted on traditional form is intended to mirror the intensities of political-economic and social-cultural violence resulting from the incorporation of particular territories (as peripheries) into the world system under duress or hegemonic power. Focusing on the notion of irrealism specifically in the context of colonial theatres (such as in the Caribbean), Niblett elaborates how the irrealism informing the theatrical-dramatic works of Caribbean artists is a response to the fact that “colonial conquest involved the near complete destruction of pre-existing social formations.” Commenting on other regions—for instance, semiperipheral Europe or “territories subject to informal colonialism”—Niblett adds: “the penetration of capitalist modes and structures has occurred in less extreme or abrupt fashion” (23). What justifies the use of such a formal component is Khalil’s attempt to think beyond the conceptual strictures of linear/official history, beyond the causal straitjacket of historicist periodization and its aesthetic correlate—that is, realism (see Jameson Reference Jameson2013:2–3).

It is this irrealist treatment of time that constitutes the decolonial or evental facet of the play. With its decolonial approach to time, A Museum in Baghdad transcends the historical vision and social-political determinations of both colonial and postcolonial discourses. The play transcends the historical vision in its refusal to think and live time/history as a linear progressive time—as prescribed by Western modernity. The past (colonial-imperial) history is, in this line of thinking, deemed a dead, extinct object from an irretrievably past stage that is meaningless to return to—in the universal progress of humanity under the aegis of technical rationality. A Museum in Baghdad transcends a merely postcolonial vision by refusing to cling either to a melancholy mode of remembering the past or to a revisionary take on the colonial-imperial accounts of it. In the postcolonial vision, the subject writes back and undertakes a revisionary approach to the (colonial-imperial) history. Narratives are driven either by a revolutionary (hence amnesiac) rupture with the past or an obsessive-compulsive rewriting of or melancholy immersion in the past, or an obsessive remembrance of it. In its irrealist aesthetics and decolonial vision, A Museum in Baghdad renders visible the geopolitical, racial, and economic situation, and the natural resources—the material conditions—of the colony, as well as relationship between the colonizer and the colonized. More importantly, it presents a speculative account of a future for the decolonized people/nation (Iraqi/Iraq) whose temporal-historical and material conditions may not be determined by either a melancholy postcolonial history or a reactionary/revolutionary postcolonial nationalism—both of which would reiterate the violence of the colonial history. Walter Mignolo’s argument confirms the point at issue here: “Decolonial time means plurality of times entangled with a Western unilinear idea of time which any ‘post’ reproduces in its imperiality” (2014:49).

Figure 5. The falling statue of Saddam Hussein toppled by the Iraqi people in the aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq, projected onto the back wall. A Museum in Baghdad, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

As directed by Erica Whyman, the transversal choral moments are among the most dramaturgically elaborate scenes, of which five are emblematic. The first choral moment (7–10) dramaturgically renders the transversal dynamics of time/history pervading A Museum in Baghdad through an intriguing juxtaposition of two scenographic details. On the one hand, we witness a condensed visual rendition of the history of Iraq spanning 1920–2010 in the form of pictures projected on the upstage wall (where cases and shelves of the museum, schematically and indicatively presented, are placed). These projections range from images of King Faisal, Gertrude Bell, Iraq’s archaeological sites, British troops, and life in 1920s Iraq to the images of Iraqi children, women, and civilians from the 2000s, the statue of Saddam Hussein being toppled by Iraqi people, and the troops and forces of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Figure 6. War planes evoke the invasion of Iraq by the US-led forces in 2003, projected behind the characters of A Museum in Baghdad. The Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

On the other hand, we witness, projected on the stage floor, some mysterious Akkadian words, as if reproduced from one of the ancient Sumerian slates. What can shed ample light on these unfathomable words is a fascinating detail from the production history concerning the process of the development of a befitting set design for A Museum in Baghdad. In her attempt to establish a thematic, visual, and linguistic orchestration between the concerns at stake in each scene of the play and their scenographic rendition in the production, the set designer Nina Dunn drew up a roster of words/ideas that she identified as the key preoccupations of the play (see box 1). Then in her attempt to remain faithful to the manifold temporal structure of the play, Dunn had the words/ideas translated into Akkadian by a specialist of ancient languages, Selena Wisnom, and projected them onto the stage floor at various choral moments.Footnote 4

Figure 7. Characters from both temporal folds stand together as a choral unit with Inanna or Mask of Warka on the back wall and Arabic words on the stage floor.

This anecdotal account, however, does not sum up the intended associations of such a dramaturgical move. Given the context of the play (Iraq)Footnote 5 and its overarching thematic preoccupations (including cyclical violence/violation, war, law, and justice), in conjunction with their striking imbrications with the principal topics of the two ancient Akkadian texts: either Hammurabi’s code of laws or the Epic of Gilgamesh, it would not be far-fetched to interpret the Akkadian letters projected onto the floor as evocative of certain parts of these two texts—particularly Hammurabi’s code of laws, the first documented human law in the world, composed c. 1755–1750 BC. The historical Hammurabi code of laws was carved onto a massive, finger-shaped black stone stele or pillar that was also among the items looted by invaders but finally rediscovered by archaeologists excavating Susa in 1901. Hammurabi’s code of laws comprises a collection of 282 rules and is one of the earliest examples of the doctrine of lex talionis written in the form of if-then laws. Hammurabi’s code of laws set fines and punishments to meet the requirements of justice and established standards for commercial interactions (Barmash Reference Barmash2020:3–18).

The second conspicuous dramaturgical rendition of a transversal-choral moment (28–31) is concerned with the play’s account of a mythic, matriarchal commune and the extirpation and burial in a pit of all the women in the group by marginalized, outcast men—the foundation of the first patriarchy. Notably, this transversal moment and its anamnestic dynamics includes the psychosomatic (though unconscious) survival of the memory of the traumatic event (inflicted on women) in the children/survivors. At this point in the play, we hear a sublimely dissonant mélange of speeches and languages that throws into relief the sheer force and violence of the slaughter of the women. The deployment of a dissonant aural dynamics for the evocation of the traumatic event is highly apt. As Josh Epstein explains: “Dissonance offers the ability to take sounds that bear a narrative relation to each other, as they unfold in time, and recombine them to surprising or critical effect in ‘an instant of time.’” Notably, he adds: “dissonance […] is also imagined to resonate with its surroundings (noise), and with the historical passage of time (rhythm) that it tries to compress” (2014:35). Another salient dramaturgical feature of the second choral moment is the way the Akkadian words on the floor are overlaid with the map of Iraq, not only enhancing the historical, geopolitical, and archaeological resonances informing A Museum in Baghdad, but also establishing a link between ancient history and law and modern history and law—metonymically represented in the text by the cartographical practice as a violent infliction of the colonial-imperial law. Such a juxtaposition also accentuates the longue durée dynamics permeating the historical vision of the play. In this scene, the image projected on the upstage wall is an ancient statue. There are numerous references throughout the play made to “the goddess” who is likely Inanna, and the image projected onto the upstage wall is clearly of the historical statue of Inanna. Inanna is also known as the Goddess or Lady of Uruk, and the Mask of Warka—the modern city near the site of the ancient city of Uruk—is also thematically and scenographically central. The Mask of Warka (or the Lady of Uruk) dates back to 3100 BCE. It is one of the earliest and most accurate representations of the human face from that period. The carved marble female face is approximately 20 cm (8 inches) tall, and was probably incorporated into a larger cult image. Most archaeologists and researchers believe that it is the representation of a deity (or goddess) and some argue that it is a depiction of Inanna.Footnote 6

Figure 8. The image of Inanna is projected onto the back wall; key words and concepts from the production, translated into Akkadian, are projected onto the stage floor. A Museum in Baghdad, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

Crucially, while the identity and historical-mythical nature of the matriarchal commune and the operative patriarchy remain indefinite and tacit in the play, the insightful dramaturgical move—counterpointing the Hammurabi code of law with the image of Inanna—renders this moment/event historically more specific and blindingly explicit. The image of Inanna (and later the Mask of Warka) metonymically corresponds to the first female commune or matriarchy—where a communal ethics, love, freedom, and eco-friendly economics reigned. And the Hammurabi code of laws—as one that relegates women to an inferior position and subordinates them to the Law of the Father (à la Lacan)—corresponds to the subsequently emerging patriarchal order.

Figure 9. A chiaroscuro display of swirling shapes and shadows, oil wells and spills evoke a state of war, pandemonium, and temporal disarray. A Museum in Baghdad, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

The third example of the revealing dramaturgical rendition of a choral/transversal moment (53–56) conjures up a kaleidoscopic and vertiginous dynamic. This transversal moment contains a farrago of numerous speeches simultaneously delivered by various characters in English and Arabic—all inundated with highly dissonant aural dynamics: screeching sounds, wailing screams, commanding summons, and elegiac ritualistic invocations. This linguistic/verbal, aural, and scenographic complex is streaked with an equally manifold visual configuration. Apart from the characters forming the chorus, we witness a chiaroscuro-like configuration (since the dominant colors are white/grey and black) with three prevailing images: blown swarms of sand; a whirlwind of macabre, grotesque shadows projected onto the walls; and projections of shattered glasses and bricks on the floor. Importantly, the images of the shards of glass gradually dissolve into more viscous and rather black swirls that simultaneously evoke oil wells and dark floods (also indicated explicitly by the chorus).

The final paradigmatic case of illuminating dramaturgical rendition occurs when the chorus delivers lines about a barbaric beheading of a native Iraqi (either by ISIS or US forces) for his unremitting fidelity to the land and his refusal to reveal the secrets to the invaders (70–81). In this scene, the table in the middle—on which relics, maps, and documents have been placed and removed, and at which various characters (including Gertrude, Ghalia, and Layla) have been working—is draped in a white shroud-like cloth in keeping with the morbid ambience of the choral moment. One of the most striking aspects of the scene is the projection of the Mask of Warka on the upstage wall, looming and presiding over various historical periods like Benjamin’s Angel of History ([1940] 2003:253–64).

In one of the final choral elegiac hymns (80–81), the three words الاَرض,الاَسرار, and مُتجذِرٌ are recurringly utilized in near-immediate juxtaposition, both in the text and in the projections. The words—translating as “secrets,” “earth/land,” and “deeply rooted”—coalesce to evoke the value of fidelity to one’s nation, history, and cultural roots as a gesture toward future-oriented fabulation and of resistance against both imperialism and phallogocentrism as modes of violence. Significantly, this is vividly attested by the way in which the ensuing words are separated from the rest of the extended choral recitation in the text, and are reiterated like a refrain within a poem as they are projected on the floor in repeated lines while the chorus delivers its speeches:

وُلدتُ فی هذه ِالمدينةِ و سأموتُ فی هذه المدينة

The projection of these words on the floor establishes a deictic and indexical link between the words (and their historical reference and semantic content) and the ground, endowing the land with a sense of deep time, longue durée, and archaeological depth. As such, birth (one’s arche or origin) and death (one’s telos or fate) are bonded together through the land—all three of which are among the vexing concerns of the play.

What pervades the dramaturgical renditions of all the choral moments in the premiere production of A Museum in Baghdad is the use of a sublime mode of “dissonance”—at visual, aural, and verbal/linguistic levels—as an aesthetic means through which an ethics of différance, event, and anamnesis (of repressed traumatic moments) is achieved. In other words, the dramaturgical dynamics developed in the production accentuate the need to deploy a nonmimetic style as an effective means of nonidentity thinking. The work’s sublime dissonance is a means of giving focus to the gaps, silences, and voices that the dominant imperial-colonial or phallogocentric discourse renders as “noise”—the voices of women, children, minorities, and victims. Such a conception of the relationship between aesthetics and ethics revolving around the notion of sublime dissonance finds corroboration in Theodor Adorno’s aesthetic theory of (late) modernist literature and arts. Dissonance, to Adorno, is the “seal” or the basic principle of modernism whereby the tension-laden dialectical relationship between the sensuous and the spiritual is thrown into relief ([1970] 1984:15, 161, 221). Adorno posits harmony and beauty as the principles of identity-thinking, assimilationism, and totalizing impulses (through which tensions and frictions are dissolved)—which together constitute the ethics of the neoliberal consumer culture. Instead, Adorno valorizes “dissonance” not only as the means through which “the semblance of the human as an ideology of the inhuman” is revealed (15), but also as a means by which “the historical emancipation from harmony as an ideal” can be achieved (161; see also 332–57). Dissonance is also a means of defying reconciliation, the reification of the mimetic, and its relation to a “petrified and alienated reality” and neutralization of culture through the principles of harmony—all of which Adorno discerns as the symptoms of the reification and immersion in commodity culture (31, 45). To counter this, Adorno poses the three principles of abstraction, dissonance, and the new (50–51, 131).

One of the most visually striking moments of the play is the scene in which Gertrude is in the glass cabinet as the sand pours down to bury her. In this scene many of the recurring thematic and dramaturgical elements of the play—the glass cabinet, the sand, and the tension-laden relationship between the acts of burial and unearthing—coalesce to create an inconclusive mise-en-abyme climax. Compared to the temporal-spatial economy of this moment in the text, its presentation in performance was far more protracted and extended. Prior to this moment, we see Gertrude putting on a scarf and entering the glass cabinet. In this highly stylized and aurally and visually orchestrated moment, sand continues to pour on Gertrude’s head, as well as the heads of the three other characters onstage: Nasiya, Layla, and Salim. In a stage detail not in the text, while Gertrude is trapped in the glass cabinet, the other characters stand in the open space surrounding it. After a long interval, as the lights grow increasingly dim, Abu Zaman suddenly arrives and calls others to help him save Gertrude by removing her from her potential burial mound—the amnesiac sands of history and/or non-time.

Figure 10. Gertrude seated in the glass cabinet with sand pouring down on her head from an invisible and mysterious source. A Museum in Baghdad, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Swan Theatre, 2019. (Screenshot by author; courtesy of Royal Shakespeare Company)

Furthermore, what this scene foregrounds, along with other scenes where the glass cabinet lights up, is the broken hourglass metaphor for A Museum in Baghdad’s deconstruction of chronological time and historicist/historiographical method. What the climactic moment in particular renders visible is the glass cabinet as a deconstructive (or evental) correlate for the hourglass (chronological time, Western history). Here we witness Gertrude enter the glass cabinet only to be buried in the downpouring sand—the imminent act of digging her out and Abu Zaman breaking the cabinet and saving Gertrude is just over the horizon. As such, the glass cabinet is a metaphorical rendition of a decolonial hourglass, that is, an open hourglass, an evental hourglass, open to the forces of history and rhythms of the events. That is why it is rendered as a dynamic and fluid stage prop that keeps being filled with sand and overflowing throughout the play. With its sands coming and going, the glass cabinet/hourglass functions as a time machine—a medium through which characters from other periods come, go, and stand in attendance waiting behind it while characters from one period occupy the foreground or centerstage.

Photography vs Archaeology

Dead Time of Historiography vs the Evental Time of Decolonial History

As Khalil recounts, the gestation of A Museum in Baghdad was a photograph of Gertrude Bell in the National Portrait Gallery in London; followed by Khalil’s meeting with the renowned Iraqi archaeologist Lamia al-Gailani Werr (awarded the fifth Gertrude Bell Memorial Gold Medal) who spoke about the 2003 looting of the Iraq Museum and efforts to reopen it (Khalil Reference Khalil2021; also Khalil Reference Khalil2019b). Therefore, though A Museum in Baghdad started its life with a photograph, Khalil made sure its life would not remain confined to the surface of the photograph, but rather made it delve into the invisible depths of the photograph through a decolonial process of evental anamnesis. In the play, Gertrude characterizes photography as a “conservative” art with a “preservative” function; it fixes and freezes time, people, and events:

GERTRUDE: A hundred years ago the first photograph was taken. That was when we humans became able to capture moments. Things. Preserving them. Holding them forever in time and space. I’ve always enjoyed taking photographs on my travels. As a reminder. A way of stopping time. (70)

Archaeology, on the other hand, is associated by Gertrude with mobility, transversality (see Certeau Reference Certeau1984), and temporal fluidity—an evental encounter with the past recognizing its inherence in the present. She continues:

GERTRUDE: Until I discovered archaeology. You all know I love to travel. Especially in this part of the world. But with archaeology I discovered time travel. The ability to travel back to the distant past. Find out the truth about how things were then, in order to better understand how they function now. (70–71)

Archaeology here is defined as an attempt to apprehend and appropriate the “deep” and experiential conditions and transcendental truths of the lived past. Equally crucial is Gertrude’s description of archaeology as a means of restoring the wholeness of an otherwise irremediably fallen present and broken knowledge, salvaging the “warped” or “muted” truth and mending the ruptures—a dialectical task: “And with that knowledge I truly believe we can overcome divides and create nations, what was broken can be healed—united” (71). Gertrude’s approach to history is akin to that of a historical materialist in emphasizing the persistence of the past in the present as a force that determines and shapes it, which stands in stark contrast to Professor Woolley’s historicist contemplation of a past that seeks to fossilize and commodify it, to trade in its merchandise of artifacts and relics.

In the same vein, through the recurring invocation and moments of unearthing and washing aground by various characters, referring to the origins of the chronologically organized objects within the seamless space of the museum, the play subtly endows the ostensibly surface-bound space of the museum with a sense of spatial and temporal-historical depth: the pits or depths that the objects came from as the Abgrund of the museum (Heidegger 1959:92–94). This renders the museum as a space for uncanny reverberations, remembrances, and visions. In keeping with the character of a museum where artifacts from different historical periods and geographical sites are assembled, Khalil’s museum is informed by a multitemporal and spectral logic. The past keeps haunting the present and the present cannot but be permeated with the past; the future is nothing but a plane determined by the dynamics through which past and present intersect and are perceived as related to one another. Khalil takes a subtle dramatic measure to vividly depict the cyclical continuity of the colonial-imperial domination/exploitation through an extractivist-capitalist logic and approach (with different methods and dynamics) while throwing into relief the question of scale. This measure involves her choice of a stable and sustained setting—to wit, the Baghdad Museum—in all three historical facets of the play. In addition, Khalil exploits the highly metatheatrical nature of the museum as a space where the ethics, aesthetics, and politics of representational and spectatorial processes are exposed. The museum, in other words, reveals the construction of culture (by an official, unitary, homogeneous discourse); thereby, the very processes of cultural and historical representation along with the ethics, ideologies, cultural politics, and discursive logic underlying them are thrown into relief. In A Museum in Baghdad, Khalil foregrounds the performative dimension of the museum by which it surpasses a merely representational function, and rather features as “an institution for the construction, legitimization, and maintenance of cultural realities” (Preziosi and Farago Reference Preziosi, Farago, Preziosi and Farago2004:2).

The Museum as a Transversal and Performative Space

Few places embody as dense an intertwining of lived and unlived memory, history, and culture as a museum—at simultaneously public and private, personal and collective, national and global levels. A museum places time and space in tandem and tension with each other by foregrounding the axis of time/history in its staging, exhibiting, ordering, and labeling of artifacts primarily based on their historical period of origin. A museum also foregrounds the role of space as a disciplinary episteme and a symbolically invested ecology of culture—rather than an inert, neutral subtextual element. As such, in a museum time thickens and space is transversally extended. In terms of space, a museum is a place where history is stitched together through the incongruous placement of objects, the museum’s seams straining under the pressure of the displaced relics. In its configuration of those historically disparate objects within the same space—which is a metonymy for the culture of the nation and beyond—based on its tacit regimes of truth(s), a museum renders the spectator-participant conscious not only of the logics and power dynamics of the extraction, placement, and ordering of the objects, but of the politics of line-drawing between and across geographies and periods. It is due to such overdetermined features that Kevin Hetherington calls museums “seeing-saying machines” that act as nodal points of emergence “in which some social relations are established and others are broken down” (2011:459). A museum is also a site where the artificiality, arbitrariness, and constructed nature of ostensibly solid and transhistorical phenomena such as nation-states are thrown into sharp relief; hence the sense of anachronism and displacement that always suffuses museums in fiction and fact—take as paradigmatic examples Nigeria, Iraq, Kuwait, Jordan, and Syria—all simply “inventions” of the British Empire (see Nixon Reference Nixon2011).

Numerous scholars, including Alan Ingram and John MacKenzie, have drawn attention to the colonial origins of the modern museum and the formative influence of museums in forging a concocted narrative about the national/cultural history and identity of the nation. Ingram, for one, attributes a “geopolitical power” to museums through which they “not only reflect and help to shape a sense of nation […] but also the parameters of legitimate knowledge and behaviour” (2019:61). As such, a museum can play an integral part in the colonial-imperial project of nation-building. At its core, a museum produces a national identity “as something that can be felt and touched” (86), reducing nationhood to symbolic objects ready for consumption by the general public. In addition, museums can function as disguised institutions for maintaining the cultural hegemony as well as the political economy of the extractivist discourse of the empire (59). A museum thus gains its canonical status in the politics of memory and nationhood through its imperial roots. Equally notable is the determining role of museums in the West in shaping and supporting an orientalist-racist discourse that pivots on a hierarchically based ontological (worldview) and epistemological (knowledge and means thereof) difference—embodied by the Other’s culture and identity. In such a discourse—mediated by the museum and further upheld by national or imperial might in obtaining the cultural treasures of the peripheral nations of the world—Western culture is depicted as progressive and superior and the non-Western Other as primitive and exotic (9).

The function of the modern museum in shaping and supporting an orientalist-extractivist ideology and racist worldview has also been interrogated by postcolonial and decolonial scholars. Walter Mignolo and Catherine Walsh, for instance, point out that museums play an enormous role in “consolidating the enunciation and therefore, the coloniality of knowledge and being” (2018:199). Along similar lines, museums have been characterized variously as “potent mechanisms in the construction and visualization of power relations between colonizer and colonized” (Barringer and Flynn 1998:5) and by MacKenzie as one of the “tool[s] of empire” (2009:7). Furthermore, MacKenzie accentuates how museums served as epistemic and epistemological tools for providing an alienating knowledge of their national, historical, and social-cultural identity, extending domination in various respects: “Museums in imperial territories were inevitably differently focused from those in Europe. In all the territories of white settlement […] they represented a western view of the world” (2009:5). MacKenzie also underscores how museums should not only be considered as mnemonic spaces through which the historical and cultural memory of a nation and the world is manipulated; they should also be perceived as discursive spaces where power and knowledge (at social-cultural, historical, and political levels) are indelibly intertwined: “Memory is itself a source of power, a means of supposedly understanding the present and divining the future” (5). And it is precisely through utilizing the power underpinning the ethics and politics of memory and museum that the A Museum in Baghdad’s Abu Zaman embodies a formidable counterhegemonic and decolonial force. Such a force is evidently reflected in his power to remember the immemorial, the repressed, and the buried; his capacity for transversal travel through various temporal layers; and his embodiment of the possibility of a future not determined by the longue durée and conjunctural cycles of imperial-colonial extraction in Iraq.

It is due to these convoluted facets and complex dynamics of the museum that A Museum in Baghdad, set in Iraq’s national museum, offers a profound decolonial critique of the entanglements and complicities of imperial capitalism and cultural imperialism both governed by the extractive logic of core-periphery dynamics.

Politics of Space, Memory, and Visibility

While museums are not politically neutral institutions, national museums set a higher standard in political functionality by playing an integral role in the legitimization of nationhood. As Craig Clunas observes, national museums function “to validate the claims to sovereignty and independence by proving through displays of archaeology and ethnography the inevitability of the existence of the actually contingent conditions that give it its very existence” (1994:319–20). Considering this manifold relation between museum and nation, there is a unique feature that distinguishes Iraq: “Iraq is the only country in the world in which the national museum is older than the nation” (Naiden Reference Naiden2007:61). It seems counterintuitive to have a national museum for a nation that does not yet exist, because “the most common kind of knowledge claimed to derive from museums is a sense of the past” (Jordanova [Reference Jordanova and Vergo1989] 2006:25). This jarring fact accentuates the status of the Iraq Museum. More significantly, it throws into relief the parallel between the sociocultural and political-economic dynamics and logics of, on the one hand, the building of the Baghdad Archaeological Museum and, on the other, the building of Iraq as an “invented” nation. Just as the former was built by means of a collection and collation of disparate objects and Mesopotamian relics into a new fabricated whole, the latter, analogously, comprised a wide variety of tribes and communities that were disparate in terms of their religions, dialects, and ethnicities (as indicated in the play: “Sunnis, Shias, Kurds, Jews” [37]). In fact, this inherent and inner/domestic disparity was engineered by Britain as a constituent part of Britain’s imperial nation-building scheme: such disparity and all the consequent tensions and conflicts necessitated the presence of a neutral (nonlocal) mediator to settle them. It also made the bargaining with the contending forces amidst such political-economic instability far easier and more profitable.

The parallel between museum-building and nation-building within the context of Iraq—coupled with all its allegorical reverberations—constitutes the crux of Khalil’s A Museum in Baghdad. The parallel is far from being a figment of Khalil’s imagination. On a political and economic level, both Iraq and the Baghdad Archaeological Museum were colonial-imperial projects or inventions. As such, both were historically driven by the extractivist logic of global/imperial capitalism whereby natural resources were extracted and relics and artifacts appropriated by the British Empire. Museum-making served as an effective sociocultural means for facilitating the colonial-imperial project of nation-building in Iraq by concocting and representing a coherent, unified, homogeneous image and narrative of Iraq’s history notwithstanding the actual heterogeneity and religious, linguistic, and ethnic differences among the local people.

One of the most conspicuous instances where this parallelism is evoked is Gertrude’s explicit indication of the function of the museum as a means of unifying the people of Iraq and consolidating the Iraqi national identity. She claims: “This isn’t about me—it’s about creating unity, nationhood […] it’s about galvanising an identity for the people of Iraq” (5). The choice of the word “galvanising” portrays Gertrude as wanting to be the driving force for patriotism among the Iraqi people. She expects the Baghdad Museum to play an essential role in the establishment of Iraq as, in Benedict Anderson’s term, an “imagined community” ([1983] 2006:6). As Silke Arnold-de Simine observes, museums foster the illusion of national solidarity as places “in which individuals are connected by the knowledge, self-perception, rules and values they hold in common and by the memory of a shared past” (2013:7). Although the various tribes in Iraq are far from having a shared past, Gertrude envisions the museum as a means of honoring the history of Mesopotamia and fabricating a sense of national unity for the people of the region no matter how different they are. In a conversation with Abu Zaman, Gertrude states: “I need to remind them of their past—so they carry it with them into a future where this nation regains its place as the most important in the region, if not the world” (19). Museum-building is part of her greater ambition to build a nation, evidenced later by her assertion of her contribution to the “creation” of Iraq, averring how she “crowned a king and made a country” (75).Footnote 7 The manifold nature of Gertrude’s role and function in Iraq and the mode of her relationship with Iraq are brought into relief in one of her conversations with Professor Woolley. A Museum in Baghdad in fact makes two explicit references to museum-building and nation-building in relation to Bell. When Woolley insidiously suggests Gertrude leave, saying “Do think seriously about what you should do next, Gertie. You’ve lots of options—perhaps you’ve done your bit here” (75), Gertrude wonders what Woolley means by his laconic and ambiguous “here.” Hassled by Gertrude, Woolley elucidates: “‘Here’ Iraq—perhaps it’s time to go home” (75). Gertrude responds, “And where exactly is that?” (75). While Woolley—expressing the typical colonial attitude—characterizes Iraq as “this ferocious, dangerous place where even the weather kills,” Gertrude first reminds Woolley of her contributions to the very genesis of the nation and then counters Woolley’s Otherizing and vilifying stance by adding: “Then don’t talk to me of ferocious weather. This is my place” (75). Notably, Gertrude does not use the word “home” but rather “place”—a strategic word implying her official role and function as a British officer rather than an affectively invested native. While the foregoing utterances reveal her dedication and investment in Iraq, they also adumbrate the reason underlying Gertrude’s refusal to go home to Britain. Latent in her hesitation is the fact that “home” was in sheer nationwide turmoil due to the 1926 general strikes over coal as a consequence of which the real Gertrude Bell’s father lost a substantial part of his fortune, influence, and income. Hence, as Bell intimates in her letters to her sister, she barely had anything meaningful to keep herself fruitfully engaged at “home” (see Bell Reference Bell and Lady Bell1927). Such shades in her character and the historical circumstances accentuate how Gertrude Bell, both as a factual and fictional character, proves an ambivalent figure appearing as at once an imperialist and an altruist/philanthropist.

Here, Gertrude stands in stark contrast to Professor Woolley, who views the museum as a colonial institution “through which agents of Empire can impose imperial ideals of the Iraq nation on the people of that geographic area” (Ingram Reference Ingram2019:59). To Woolley, the Baghdad Museum is more like a shell institution for the acquisition and storage of cultural relics before their transfer to London. MacKenzie’s argument concerning the colonial museum is illuminating:

The colonial museum, in some respects, heightened the theme of the raiding of nature. It often symbolised the dispossession of land and culture by whites through the rapid acquisition of specimens and artefacts. Such colonial acquisitiveness occurred on a global scale, representing a worldwide movement brokered by imperial power. The museum’s intellectual framework, its collecting habits, and so many of its methods were closely bound up with the nature and practices of imperialism. (2009:4)

The hidden side of this colonial act of cultural resource extraction and its cultural imperialist apparatus is disclosed to be the British Museum, maintained as a spectral element throughout the play and fleetingly invoked by Woolley but always haunting the Iraq Museum as its parasitical double sucking the lifeblood out of it. Referring to the statue of the goddess Inanna, Woolley says: “She’d look better in a nice secure display cabinet at the British Museum. I’m glad you got her back in one piece” (26). Such references evoke the colonial genealogy of museums more generally: “It’s worth remembering that while there’s a lot of time, money, labor, and attention invested in these particular buildings—these monuments, these physical, material manifestations—such formations are always haunted by theft and death” (Copeland Reference Copeland2017:261). In the play, Gertrude is uneasy about Woolley’s request to take the statue to the British Museum, telling him that she “won’t lend her [the statue] unless I have it in writing that she’ll return: I know your ‘borrowing’ and don’t forget the Iraq laws of antiquities” (5). This immediately reveals the politicized nature of the museum-building process, particularly Britain’s influence and control over Iraq’s cultural heritage. Gertrude’s sarcastic allusion to “borrowing” and her insinuation that Woolley’s activities are latently part of the contemporaneous looting of Iraq’s cultural artifacts by the British Museum are all the more relevant in light of how in recent years the British Museum (alongside many other British, European, and US American ones) has come under scrutiny for its involvement in looting from colonized countries. This issue is further explored in the play when the statue is returned to Iraq in 2006. This event, and the question of where the statue belongs, is ardently debated in the 2006 fold of the play by Ghalia, Layla, and Mohammed. Layla presents the most scathing and incisive critique of the Baghdad Museum, arguing that it is a “globalised, commodified, Western version of a museum” that shapes Iraq’s “historical narrative in the way that suits those in power” (25). Even Layla’s concession that Gertrude was “out for her own ends” and that “she basically put herself in charge and shared the spoils with her mates” (27) fails to consider the structural implications of a museum built to reflect the national history of a country (constituted by the British Empire only five years before the inauguration of the museum). This is evidenced by her placing the blame for the colonial institution on individuals rather than on systems.

In A Museum in Baghdad Gertrude is depicted as being deeply involved with the construction of the Baghdad Museum, but her work goes beyond that—as she states, her job is to “Make a country” (18). The article Gertrude writes in the play, and reads to Salim, lays bare her political vision and ambitions:

GERTRUDE: The Mesopotamian lands cannot fail to expand economically with great rapidity and economic development will go hand in hand with the increase of political importance. We confidently anticipate that Baghdad, with its brilliant commercial future, will in a few decades replace Damascus as the capital city of the Arab world […] and we conceive that our task is not only to fit it for the part which it will play, but also to order our conduct of its affairs so as to establish lasting amity […] and confidence between ourselves and the Arab race, whatever modifications the future may bring to their political status. (57)

Akin to her historical counterpart, the Gertrude Bell of the play takes a sympathetic and respectful stance towards the local population even while serving as a staunch agent of the British Empire. This is further attested by her endorsement of the fledgling state of Iraq even as she affirms her conviction about the necessity of the British presence in the still politically and economically immature country, guiding it towards becoming a more stable country. She tells her assistant Salim: “There’d be chaos if we left now” (66).

Nevertheless, she is insightful enough to be riven with doubt as to whether her aspiration to create a united nation will ever be realized. She says to Salim: “I have such hope for our British mandate here. But when I raise my eyes across the border to Syria and see how the French mandate is playing out there—it’s scandalous. It can only lead to war and bloodshed” (56). The ensuing dialogue demonstrates the flaws and limits of her political vision—particularly regarding Britain as a guardian state embodying democracy, science, and rationality:

SALIM: “Honorary Director”?

GERTRUDE: I’m just keeping the seat warm.

SALIM: But who else could do that job?

GERTRUDE: An Iraqi I would hope.

SALIM: Why?

GERTRUDE: Because this is Iraq.

SALIM: But it is ruled by Great Britain, so an English director would be better.

GERTRUDE: It is ruled by an Arab monarch.

SALIM: Under Britain’s mandate for twenty-five years.

GERTRUDE: You don’t think that’s good for Iraq? There’d be chaos if we left now.

SALIM: You are right.

GERTRUDE: After that we will give you independence.

SALIM: Independence is never given, it is always taken. (66–67)

As a typical imperial agent, Woolley does not share Gertrude’s ambition to build a nation; he defines Iraq as a “made-up land” (78), a shell nation built for the enrichment of the British Empire. He also reminds Gertrude, with a derisive tone, how “there was no such country till five years ago” (5). He describes Iraq as a nation created by Britain in the colonizer’s geopolitical and economic interests. As Toby Dodge writes, “British colonial officials had little choice but to strive to understand Iraq in terms that were familiar to them” (2003:1). It is evident that when we discuss the history of Iraq, we are discussing an imagined history, a simulacrum, or a narrationFootnote 8 of what the orientalist, colonial imagination wanted Iraq to be, not necessarily what it actually was, or the whole its various tribes/peoples imagined themselves being part of.

In the play, Gertrude is acutely cognizant of the heterogeneity of the groups that inhabited the former provinces of the Ottoman Empire and the consequent challenge—what she calls “the impossible task—an unwinnable game […] of mak[ing] a country”; she muses: “What did they all have in common? Not language. Not tradition” (18). Her naïveté lies in her belief that she can unite these diverse groups on the common ground of history: “Immovable, intractable, unchangeable history. A nation needs to be able to look into the eyes of the past and understand where they come from. What legacy they carry in them” (18–19). She aims to build the museum as a reminder to the Iraqi tribes of the fact that they are the joint inheritors of the magnificent Mesopotamian civilization (19). Gertrude presents the collective past as an objective, identifiable fact of history that her museum is only reflecting, intentionally glossing over the fact that the very establishment of her museum in Baghdad is an imperial, extractivist mission and thus contingent upon a number of factors outside of her control. In this sense, when Gertrude self-contentedly claims the fulfillment of her mission by “bringing order where there isn’t one” (14), she refers not only to the museum, but also to the entire Iraqi nation.

The museum allegorically represents Iraq, foregrounding how the historical, cultural, and political dimensions of the nation are embroiled in an interminable process of making and unmaking due to the inimical influence of the resource-driven, cartographical practices of (British) imperial capitalism. As Sherko Kirmanj states, “although the Iraqis have lived together for nearly a century, the people are not and never have been united […] The three provinces of the Ottoman Empire were never united politically and culturally by feelings or notions of a collective identity” (2013:11). In the play, Kirmanj’s considerations find confirmation in Woolley’s words: “Look around […] The tribes are twitchy—Sunnis, Shias, Kurds, Jews […] Imagine taking an Englishman, Scotsman, Welshman, and a Paddy—telling them they are one family—making them share one house and locking the door on them. Go back in a week and they’ll each have barricaded themselves in a room” (37). Indeed, what both Iraq and the museum share is “the logic of displacement” (see Bhabha Reference Bhabha1994:1, 109, 126, 207; Derrida [1972] 2004) in that they take a colonial-imperial act of symbolic violence and externally induced formation as their points of origin. Indeed, originary displacement attests to how neither the museum nor the nation stemmed from an organic, historically evolving process of becoming conscious of shared values, history, territorial ties, religious or linguistic commonalities, etc. The ironic move in Gertrude’s attempt to “house” Iraq neglects how “displacement” is an inherent feature of museums. As Una Chaudhuri states:

[O]nly those things are put in museums that have no “organic” place within a society, because they either belong to a different time or to a different place. The museum contains and stages difference and, in so doing, produces an artificial homogeneity in the surrounding culture. ([1995] 2000:120)

The different attitudes of Gertrude and Woolley toward the museum in particular and toward Iraq in general are thrown into relief by their disputes over artifacts and relics. There is a recurring sentence in the play, a question Woolley frequently asks Gertrude: “What’s in it for me?” (4). This simple sentence is the perfect expression of the colonizer’s selfishness, the absolute indifference towards the local population’s cultural values.

Later in the play in a reverberating evental “anamnesis” moment, Woolley mentions a recent discovery his team has made: the 4,500-year-old royal cemetery in Ur, what Woolley calls “The Great Death Pit.” British archaeologists discovered the dead body of a king accompanied by “the bodies of a large number of people who must have been sacrificed in order that they might accompany the king” (51). Woolley is exalted by the discovery; upon learning that 68 of the 74 people were women, Gertrude is mournful: “All these women are laid out neatly and you presume that means a neat—a willing death. But I disagree: death is not neat or easy. They were forced to drink that poison—daggers held over them. Then they were burned. Incinerated. Out of existence. […] Sixty-eight nameless, forgotten, dead, burnt women, that’s what” (53). By fostering subtle resonances between King Ur’s infliction of violence and objectification of women, servants, and lower classes and the imperial-colonial violence inflicted on Iraq and Iraqi people, A Museum in Baghdad asserts that this past moment in Mesopotamian history should not be treated as dead and gone but as a living, persistently present moment traversing the past, present, and a speculative future. The ethical-historical imperative of discerning the transversal resonances is cogently delivered by counterpointing Gertrude and Woolley, each of whom embodies one of these two approaches to history: history as dead and a phenomenon of the past or history as a transversally present and living phenomenon informing the present.

Gertrude and Woolley’s conflicting approaches to the site and the ethical, epistemological, and ideological differences it evokes can be further illuminated by referring to two contrasting attitudes towards history as elaborated by Walter Benjamin: historical materialism and historicism. As Benjamin argues, “a historical materialist cannot do without the notion of a present which is not a transition, but in which time takes a stand and has come to a standstill. For this notion defines the present in which he himself is writing history. Historicism gives the ‘eternal’ image of the past; historical materialism supplies a unique experience with the past” ([1940] 2003:396). In other words, historicism is conservative precisely because it insists so strenuously on the pastness of the past. The historical materialist, however, refuses to endorse the notion that history is over or, in any sense, complete. Elsewhere, Benjamin presents historical materialism—with its concern for the marginal, the silenced, and the evental, and its substitution of discontinuity for continuity—as the alternative to historicism:

Historicism presents an eternal image of the past, historical materialism a specific and unique engagement with it. The substitution of the act of construction for the epic dimension proves to be the condition of this engagement. […] The task of historical materialism is to set to work an engagement with history original to every new present. It has recourse to a consciousness of the present that shatters the continuum of history. Historical materialism conceives historical understanding as an after-life of that which is understood, whose pulse can still be felt in the present. (352)

In A Museum in Baghdad, these two approaches are represented by Gertrude’s two professional interests: photography and archaeology. To Gertrude, the former is associated with a static conception of time: the past as a finished and sealed product. The latter is associated with a fluid conception of time: the past as an open process, the past as always ajar and open to partial retrieval and revival, decolonial reinscription, and “evental” reexperience—history/time as unmasterable and as slippery as sand.

Decolonizing the Museum and Its (Arti)Facts

The 2006 Fold

Two of the most salient functions of modern museums are the constitution of knowledge and historical evidence, and the coordination of aesthetic experience by attributing artistic value to objects. Corresponding with this twofold function of the museum, modern museums appear in two distinct forms: museums of artifact and museums of art—one informed by a scientific discourse and the other by a standard of artistic merit (see Ingram Reference Ingram2019:60). Museums of art give the public a place to temporarily detach themselves from the daily personal and sociosymbolic order, refine their senses, and appreciate beauty of objects. A national museum of artifacts, on the other hand, “acts as a key site of promotion of the existence and validity of the state formation. It does so with particular force in that the discursive practices at the heart of the museum lay claim to scientific objectivity, to a transcendental mimesis of what is ‘out there’” (Clunas Reference Clunas1994:319). MacKenzie asserts how the mere act of organizing and exhibiting cultural artifacts—“the weird and the wonderful, exotica that seemed initially to be unknowable and unfathomable”—makes them appear as fathomable (the illusion of knowledge) by bringing them “into the realm of the potentially known and understood” (2009:1). The museum asserts its cultural power by validating the objects within it as somehow worthy of display, as well as imbuing the objects with a sense of meaning and symbolic importance that might not necessarily have been the case had they been left “unframed.”

The epistemic-pedagogical aspect of museums, coupled with their power of attributing artistic merit to objects, creates the impression that cultural artifacts and relics truly belong in museums. These questions of value, evaluation, and belonging in relation to place/placing, location, and dislocation recur throughout Khalil’s A Museum in Baghdad, pervading both historical folds. In the 1926 fold, the discussions regarding where the relics of Iraq belong revolve around whether the Baghdad Museum or the British Museum would be the safer home for those artifacts:

WOOLLEY: From what I hear they don’t think your laws are stringent enough.

GERTRUDE: Of course they are. What is found in their country belongs to them. But you lot do need an incentive to dig in the first place.

WOOLLEY: I predict it’ll all be back to the BM in time for tea when civil war erupts again and they go back to their tribes.

(A beat.)

GERTRUDE: What do you think, Abu Zaman—as an Iraqi?

WOOLLEY: He’s no fool—he knows she’d [the statue of the goddess] be safer in Blighty.

ABU ZAMAN: (With chorus of Ghalia) Safer? (5–6)

As is evident here, in a (neo)colonial context, where the artifact belongs is determined by where it is safe, that is, where its value as a commodity can be safeguarded. And given Iraq’s unstable sociopolitical state caused by the violent extractivist acts of colonization and globalization, such a safe place cannot be anywhere but within the imperial state. In the 2006 fold, however, this issue is given a more sophisticated turn in the antagonism between Ghalia and Layla. To Ghalia, whose dubious position straddles cosmopolitan and global neoliberalism, historical artifacts “belong to the world” (45), hence their display in museums. To Layla, on the other hand, they belong in their original context, that is, on the sites where they were found:

GHALIA: But Layla is a purist—she believes artifacts should be left where they are found, experienced in that context. Taking them out of the ground is probably a step too far.

MOHAMMED: What?