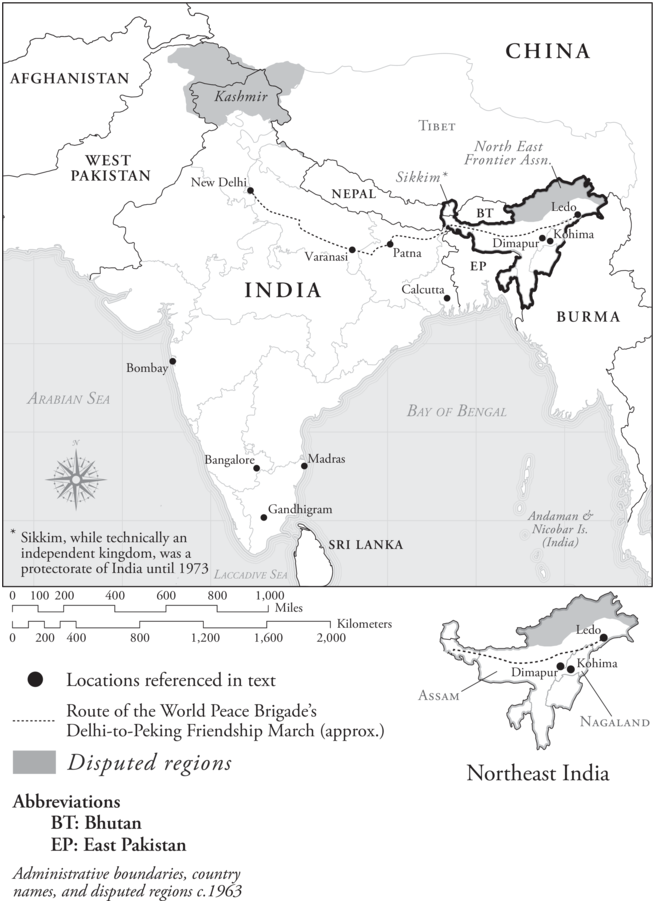

Map 6.1 Southern Asia in the aftermath of the 1962 Sino-Indian War.

Many of the unofficial advocates for states-in-waiting, for nationalist insurgent movements claiming statehood, were individuals affiliated or identified with the international peace movement. At times, these transnational advocates found themselves championing independence struggles in states-in-waiting that were situated within newly decolonized postcolonial nation-states. While some within these postcolonial state governments may themselves have relied on these advocates during their own independence struggles, they opposed such advocacy after they won their independence, since it had the potential to undermine their own state sovereignty. The 1963 Friendship March – launched by the World Peace Brigade, a transnational civil society organization set up to find peaceful solutions to global decolonization, exemplified this contradiction. The Friendship March started in New Delhi, India, and intended to cross the Chinese border in the immediate aftermath of the 1962 Sino-Indian War.

Sino-Indian War Zones

Following Indian independence (1947) and the victory of the Chinese Communist Party in the Chinese civil war, which resulted in the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (1949), an uneasy truce between India and China allowed each to build military installations in the regions where their borders remained unresolved: Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh/North East Frontier Agency (located in Northeast India, the same region as Nagaland, a territory struggling for independence from India). In October 1962, Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian prime minister, announced that India would clear what he considered Indian territory of Chinese military incursions, and China invaded India.Footnote 1 The Indian army was already stretched thin, with peacekeeping commitments to the UN in Congo (due to Katanga’s attempted secession from Congo) as well as with its ongoing “pacification” efforts in Nagaland.Footnote 2 The Chinese invasion completely routed the Indian military. After making a statement of borderland dominance, China declared a ceasefire and withdrew from most of its military advances so that it did not have to respond to the international pressure that would have accompanied a more permanent occupation.

For Indians, the defeat stung bitterly. In the words of Nehru’s biographer, Sarvepalli Gopal, “No one who lived in India through the winter months of 1962 can forget the deep humiliation felt by all Indians.”Footnote 3 The 1962 Sino-Indian War is often considered an end date – of nonalignment, of hindi-chini-bhai-bhai (“India and China as brothers,” a 1950s Indian catchphrase for diplomacy with China); of domestic Nehruvianism (the balance between state-planned economic centralization and individual freedoms); and, eventually, of Nehru himself, who died in May 1964.Footnote 4 While his health had been unstable throughout the 1960s, it is possible that the trauma of defeat accelerated Nehru’s death. The 1962 war highlighted and exacerbated the many acute challenges facing the Indian central government, instantiating the frame of national security around India’s “fissiparous tendencies” – its regional autonomic demands – especially in regions that had experienced Chinese invasion: the Indian Northeast and Kashmir. The 1962 war lasted just over a month, but it had ongoing effects in securitizing and nationalizing borderlands regions, especially as it did not resolve the disputed border between India and China.Footnote 5 Three thousand Indian citizens of Chinese origin were interned in camps in India, and tribal peoples in Northeast India came to be racialized as “chinki” – foreign, and visually linked to a national foe.Footnote 6

Neville Maxwell – an Australian journalist who visited Nagaland in Northeast India as part of a 1960 reporting mission and who was a contributing writer to the Minority Rights Group, a nongovernmental organization originally set up to address the Nagas’ nationalist claims – wrote the formative revisionist account of the Sino-Indian War.Footnote 7 This account was revisionist because Maxwell blamed Nehru for deliberately provoking the Chinese: the “Indian side is impaled on Nehru’s folly of declaring India’s boundaries fixed, final and non-negotiable … A boundary dispute is soluble only in the context of negotiations.”Footnote 8 A harsh critic of Nehru, Maxwell considered India not only “the product of the British imperium,” but also more fixed-boundary–centric than empire had ever been.Footnote 9 He concurred with the belief that decolonization internationalized imperial boundaries, making the more permeable border zones of empire into hard borders between nation-states. From this perspective, the ambiguity of empire had allowed for more political flexibility for some subject peoples, at least from a perception that did not focus on the extreme violence and disenfranchisement of most forms of imperial rule.

Maxwell’s critique of India as “Bharat” (or political India) – that it was postimperial rather than anticolonial – remains an important corrective to visions of India that overlook continuities between empire and independence.Footnote 10 Yet his focus on the constitutional, juridical mode of Indian politics as its defining feature ignored the India that had become independent in popular understanding by embracing Gandhi’s saintly idiom of politics, which had served as an inspiration for the postwar international peace movement and had been enmeshed in transnational anti-imperialism during the interwar era.Footnote 11 This India had achieved independence through nonviolence (at least, in the general view), with transnational advocacy and support from many of Maxwell’s own colleagues and friends, and had held an internationalist political vision that stretched beyond India’s territorial borders.Footnote 12 Gandhi himself had argued that his “ambition is much higher than independence. Through the deliverance of India, I seek to deliver the so-called weaker races of the world.”Footnote 13

The Friendship March’s Foundational Disagreements

In response to growing tensions between India and China, the World Peace Brigade began planning a “friendship march” scheduled to cross the Indian Northeast on its planned route from New Delhi to Peking. However, the spring of 1963 was not a felicitous moment to attempt a peaceful crossing of the Sino-Indian border to improve Sino-Indian relations: before the march could start, war broke out between the two countries on October 20, 1962, ending a month later.Footnote 14 Regardless, the Brigade went ahead with the march on schedule.

In India, the march was predominantly identified with Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), the leader of the Brigade’s Asian Regional Council, and led by his lieutenants Siddharaj Dhadda, Suresh Ram, and Muthukumaraswamy Aramvalarthanathan (M. Aram). JP was an Indian civil society organizer with a significant national and international profile who played a leadership role in India and abroad through the Sarvodaya movement, a civil society program that continued Gandhian nonviolent activism after Indian independence.Footnote 15 Alongside Dhadda, Ram, and Aram (who were also important members of the Sarvodaya movement, as were most all Indian Brigade members), JP directed the march with Americans Ed Lazar and Charles C. (Charlie) Walker of the American Friends Service Committee, a US-based Quaker civil society organization. The enterprise totaled 19 marchers – 11 Indian and 5 American, with Japanese, Burmese, and British members of the Brigade cycling in and out.Footnote 16 Echoing Gandhi’s strategy for peaceful political change and mass mobilization, it charted its course through Sarvodaya ashrams, holding meetings and rallies along the way that drew 1,500–4,000 interested local participants.Footnote 17 JP’s three lieutenants were dedicated Gandhians whose efforts preceded and exceeded that of the Brigade. Ram had recently closed up the Brigade’s Africa Freedom Action Project in Dar es Salaam; Dhadda had become an anti-capitalist campaigner, taking on both the Indian government and multinational corporations in Indian court;Footnote 18 and M. Aram went on to champion peace in Nagaland.Footnote 19 Unfortunately, symptomatic of the rift in the Brigade community between its Western and Sarvodaya members, Ram, Dhadda, and Aram’s views on strategy and their deep experiences with the political realities in India did not seem to drive the Brigade’s own organizational dialogue concerning the march.

Before it even left Delhi, controversy hindered the Brigade’s transnational mission. Western pacifists sharply disagreed with Indian Gandhians who refused to condemn Indian state violence during the 1962 Sino-Indian War as well as in Nagaland and Kashmir. The Chinese government, viewing the march as “a group of Indian reactionaries in collusion with US imperialists” instead of as a neutral, international peace project, pressured Burma, Pakistan, and the British in Hong Kong to deny the marchers visas.Footnote 20 In addition, two of the Brigade’s leaders were also engaged in transnational advocacy on behalf of nationalist movements in Nagaland and Tibet, territories, respectively within India and China, who strongly opposed such struggles for independence.

Descriptions of these various controversies come through mostly in the correspondence of the Brigade’s Western members, for several possible reasons: The march had a strong American presence and the Brigade’s North American chairman, A. J. Muste, remained in New York and therefore needed to be notified in writing of his lieutenants’ activities. In addition, since many of the controversies swirling around the march dealt with questions of Southern Asian security, Western members of the Brigade needed to receive extensive background to understand them, while the political contexts encompassing Tibet, Nagaland, and Sino-Indian border disputes were well known to Indian Brigade members. It may also be that the Brigade’s disagreements and divergences concerning these geopolitical hotspots were less important from the primary perspective of Indian Brigade members, who wrote about them more obliquely and with seemingly less vehemence.Footnote 21 Conversely, because the questions of Tibet, Nagaland, and the Sino-Indian border concerned Indian national security and state-building, these issues could have been too politically charged for Indian Brigade members to feel comfortable addressing them directly in writing. Indian Brigade members, particularly J. P. Narayan, had domestic influence and responsibilities – therefore, a lot more at stake during the march than did their Western counterparts.

In addition, the Cold War hedged in the narrow path of transnationalism. In theory, human rights and development, as well as activism for disarmament, peace, and racial equality, were realms where the Cold War’s binary (which demanded that a state or organization identify as either capitalist or as communist) did not have to bind political action.Footnote 22 However, on the Delhi-to-Peking Friendship March, the Brigade found itself caught in the Cold War trap. While the Brigade saw itself as unaligned, the Cold War context still mattered – but not in terms of an us-versus-them dualism. Disentangling the impact of the Cold War on the Brigade’s Friendship March is not a question of “taking off” or “reading through” a “Cold War lens.”Footnote 23 Rather, it is the recognition that the neutrality of an allegedly apolitical transnational movement was not value-neutral. The Brigade could not escape politics, whether they be the nationalist politics of its leaders’ advocacy, the national politics of the countries in which it operated, or the international political environment in which their endeavors were embedded. Instead, the march and the personal and ideological conflicts it roused became a new forum for how these structural politics played out.Footnote 24

The controversy over the correct understanding of nonviolence arose at the march’s launch, when some Western supporters of the Brigade challenged the march for not adhering to its apolitical, nonviolent, non-national aspirations. Particular Western members of the Brigade community felt that the Indian state was not living up to its Gandhian promise of peaceful political action and that the Sarvodaya movement did not properly condemn the Indian government’s violence in the Sino-Indian War and against Naga nationalist insurgents within the Indian state. For example, Bertrand Russell, the elder statesman of the international peace movement, was deeply “saddened” that the Gandhi Peace Foundation (one of the parent organizations and funders of the Brigade) had not spoken up for the peaceful resolution of the Sino-Indian dispute and “for an end to the cruel war against the Naga.”Footnote 25 Russell argued that “peace should be [the] object” of the Sarvodaya movement instead of the organization’s being run as an arm of Indian “government policy.”Footnote 26 As with many Western supporters of the Brigade, Russell did not fully comprehend or sympathize with the domestic political challenges facing Sarvodaya movement members; it was significantly easier to criticize the Indian government when one was not an Indian citizen. That reality also gave Russell space to compare what India considered its own nation-building project with European colonialism: “It is no more justified for India to seek to set up puppet spokesmen for the Naga while she uses her army to destroy villages and torture people, than it was for the French in Algeria.”Footnote 27

At the same time, Indian Gandhians themselves valued British march organizer and Brigade member Reverend Michael Scott’s gift for empathy and moral sensitivity, which crossed cultural boundaries. Shankarrao Deo, a Sarvodaya member of the march, was struck by Scott’s “simple” and “noble” heart.Footnote 28 Writing in the march’s first month of progress, Deo appreciated Scott’s “friendliness and readiness to understand” the complexity of the pacifist position for Indian Gandhians in the wake of the Sino-Indian War.Footnote 29 This same acceptance, with shades of gray, that allowed the explicitly nonviolent Sarvodaya movement to support its government during wartime mirrored Scott’s support for nationalist claimants, such as Nagas, who engaged in violence.

Marchers from the United States, however, found the position of Indian Gandhians frustrating. For Brigade member Ed Lazar, the top-down control of the Gandhian movement and its “centralized decision-making apparatuses” were exasperating: “Two men – Vinoba [Bhave] and JP – make the decisions (with rare exceptions), all important matters are referred to them for ‘blessings.’”Footnote 30 Lazar thought that this centralization meant that peace “workers’ initiative has been snuffed out.” If “sainthood” became “a requirement for nonviolent action” then “bold non-violent experiments” would never get off the ground.Footnote 31 His criticism of the Sarvodaya movement contained elements of chauvinism, negatively contrasting Eastern “saintly” passivity to Western “bold experiments.” Part of Lazar’s discomfort with the culture of Sarvodaya peace workers was that in his “own group” (meaning among the Americans – a revealing possessive for an allegedly international endeavor), he was “dealing” with a fair amount of “guru phobia.”Footnote 32

The US battalion of the Brigade found the “saintly idiom” of Indian politics an uncomfortable fit. Born during the Indian independence movement, that idiom was the political mode that Gandhi used to bridge the gap between the elite Congress Party and the mass movement.Footnote 33 Saintly politics focused on voluntary sacrifice, appealing to a person’s best self. It promoted nonviolence even at the potential cost of the individual’s life and livelihood. In theory, the saintly idiom attempted to reform politics not through the exercise of power but by remaining at a distance from the functions of government. This form of political expression inspired the World Peace Brigade’s creation. It also provided an impossibly high standard and burden on its individual members: that they behave like twentieth-century saints.

Another Western criticism of the relationship between the Sarvodaya movement and the Indian government was reflected in the debate on whether Brigade leaders could publicly take personal political stances that undermined the march’s overarching purpose. In January 1963, two months before the march set off, one of JP’s lieutenants, Siddharaj Dhadda, wrote to Muste on the edits the Brigade’s Asian Regional Council had made to the march’s “aims and objectives” document:

Two things have been omitted. One, the reference to the exclusion of China from the UN … The other clause omitted is where you had said that “Individual Marchers should be free to voice opposition to war etc.” We thought that no distinction need be made between what individual marchers could say and what the group could say.Footnote 34

The Asian Regional Council’s (i.e., the Indian) revisions highlighted the ongoing division within the Brigade between members who supported pacifism as the abstention from violence and those who did not disavow violence for the purpose of self-defense or political justice. The second position justified Indian state violence against alleged Chinese aggression during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. Dhadda’s comments to Muste on the march’s aims and objectives articulated, then elided, the differences between the individual person and the collective Brigade as the unit of political action. The members of the Brigade preferred to operate as individuals rather than as an organization, because doing so allowed for more freedom to speak out on issues – but for less cohesion. Yet, in spite of its inclination toward individual political freedom, the Asian Regional Council did not want to be the sponsoring organization for Westerners who actively criticized the Indian government, and experience the repercussions for that criticism.

Transnational Advocacy versus State Sovereignty

As with most postcolonial states, when India gained its independence in 1947, it forcefully opposed the independence of any territories within its newly sovereign boundaries.Footnote 35 Post-independence, India made the case for self-determination for nation-states, not for their subsidiary units.Footnote 36 This practical ideological transition from anticolonial nationalist movement seeking independence to postcolonial state working to govern its territory highlighted the tension between transnational advocacy and state sovereignty: on the one hand, the decolonizing world gained statehood and international recognition through membership in the state-centric United Nations; on the other, liberation movements and advocacy networks practiced politics beyond the forms and boundaries of nations and states.Footnote 37 Transnational movements sought to transcend the necessities and controls of the state as the constituent unit of international order. Yet, as the contradictions faced by the World Peace Brigade and other transnational advocates made clear, such transcendence was impossible. Instead, transnational movements themselves became conduits for conflict about the nationalizing process – about which grouping of political “selves” would be “determined” a state, and by whom.

Post-independence India was riddled with what Nehru called its “fissiparous tendencies” – the destabilizing questions of Kashmir, Sikh and Tamil nationalisms, linguistic movements particularly (but not exclusively) in South India and in Assam, and labor/class/caste unrest. For Nehru, “separateness has always been the weakness of India. Fissiparous tendencies, whether they belong to Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians or others, are very dangerous and wrong tendencies. They belong to petty and backward minds.”Footnote 38 They threatened the rule of the Indian Union government and the fundamental project of an independent India, the creation of an Indian nation.

These claims of difference or separateness – linguistic, ethnic, religious, etc. – could overlap and exacerbate each other. For example, representatives from “tribal” or hill peoples in Assam (which included the Naga Hills until 1963) argued in 1961, “[I]f Assamese becomes the sole official language of the [Indian] State [of Assam], the people of the Hills in particular will suffer from serious handicaps”; therefore, they continued, the Assam Language Act of 1960 needed to be repealed, or “Separate States created.”Footnote 39 Lack of respect for linguistic differences inflamed ethnic differences. While demands for autonomy were usually mobilized around a single claim of difference – of nation, language, ethnicity, religion, etc. – multiple strands of difference could underlie each particular claim.

Not all of these fissiparous tendencies were presumed to be equally dangerous to the Indian state. In the Northeast, the Indian government usually squashed or ignored tribal peoples’ claims when they were mobilized along religious lines (often around particular Protestant denominations) – the shadow of the 1947 India–Pakistan partition meant that religious mobilization threatened the ideological foundations of independent India – but listened to some degree when they framed claims of resistance on the basis of ethnicity or language.Footnote 40 Linguistic or ethnic claims in the Northeast were constructed around anti-Assamese or anti-Bengali sentiment, rather than against the Indian central government; tribal claims in Northeast India were appealed to the Indian central government for support against the State of Assam. As a nationalist leader, Nehru had been influenced by the Soviet pattern of managing a multiethnic polity during the interwar era.Footnote 41

Nationalist movements within nation-states maneuvered across geopolitical scales – that is, between spheres of local, national, regional, international, or global politics – to find support for their claims. For example, they might seek backing from the central government to circumnavigate the immediate oppressive rule of local authorities.Footnote 42 (Interestingly, this strategy paralleled how activists in the US civil rights movement called on the US federal government to intercede to end the legal discrimination of US states against Black American citizens.) Taking this strategy to a different political arena, some minority nationalists then sought to “jump” past their ruling national government to petition the United Nations if they felt that their central government was not a viable negotiating partner. These processes were far from unique in the Indian (or the US) circumstances. Nationalist movements and minority groups made self-determinist claims on local, regional, national – and international – bases as a matter of practical policy.Footnote 43

The 1962 Sino-Indian War placed the rubric of national security over India’s fissiparous tendencies. Some of India’s internal demands for autonomy have had an obvious international dynamic, such as the demands made by Kashmir, the subject of multiple wars between India and Pakistan. Others, like Nagaland, held latent international dimensions. Still others, such as the Dravidian and Tamil demands in Madras State/Tamil Nadu and for a Sikh Khalistan in Punjab during the early 1960s, were more domestically separatist, though later they drew upon significant diaspora support. Nevertheless, they all composed the brew of “anti-national” movements (in the terminology of India’s central government) with which the Indian Union had to contend.Footnote 44

At the moment of India’s international-legal creation in 1947, the British Raj’s colonial sovereignty over that country was divided into two parts and handed over to the Congress Party and the Muslim League, who led the new governments of India and Pakistan, respectively. Decolonization did not mean that postcolonial India dissolved into its many constituent pieces (Princely States, Frontier Agencies, Excluded Territories, the remaining French and Portuguese colonial enclaves, etc.) that then had an opportunity to decide what their postcolonial political form would be.Footnote 45 Instead, decolonization meant a power transfer from one authority to two others, newly created. The negotiations that might have happened in a hypothetical constitutional convention occurred in the ways that the independent government of India (and Pakistan) dealt with their fissiparous tendencies. Into this violent and potentially violent situation, the Indian Gandhians of the Sarvodaya movement stepped, with their international allies from the World Peace Brigade, seeking to revitalize India’s nonviolent political roots by tackling its postcolonial conflicts.

The 1960s decolonization crises on the African continent – in Congo, South West Africa, Zambia, Rhodesia, and elsewhere – may have seemed far removed from India; however, regional political elites in the Northeast were aware of the similarities between those crises and their own tense political environment. The Assam Tribune, an English-language daily tied to the ruling Assam State Congress Party, repeatedly gave significant page space to the UN intervention in Congo (1960–1965) to halt the secession of Katanga.Footnote 46 There was great regional interest in and attention to questions of secession in postcolonial states because Assamese elites felt threatened by the prospect of insurgency from “tribal” peoples in the Naga Hills and elsewhere who demanded autonomy or independence. For those in Northeast India – and in India in general – questions of “sub”-nationalist insurgency and claims-making were both a national and a global phenomenon, despite ruling governments’ efforts to localize them.

Two weeks after Dhadda’s note to Muste on the march’s goals, the latter wrote to Michael Scott on the question of whether Scott was “free to raise the Naga matter,” on the Friendship MarchFootnote 47 – meaning, whether Scott could bring up the issue of the nationalist movement in the Naga Hills to break free of postcolonial India, a struggle supported by Scott and others associated with the march. Muste did not want “special” political concerns, such as the Naga question, and their public discussions to distract from “one’s fundamental attitude toward the issue of war and violence.”Footnote 48 Brigade member Bayard Rustin, whose 1930s membership in the Communist Party and 1950s prosecution for homosexuality had sidelined him within the US civil rights movement, brought up fears that Indian public opinion against Scott’s “intervention” on “the Naga question” would “effect [Scott’s] usefulness” to the march. In response to Rustin’s concerns, Muste decided that Scott’s role should be up to the Brigade’s Indian members, who resolved that Scott’s Naga advocacy did not make him ineligible to participate. However, Muste warned Scott, “this should not be taken to indicate complete freedom.” The same rules that applied to Scott would apply to Indian members of the march, who “were deeply concerned about the release of Sheikh Abdullah,” the Kashmiri leader imprisoned in India.Footnote 49 Muste danced around the hot-button issue of individual positions in contrast to group identification and cohesion. By comparing Scott’s Naga advocacy with that of JP for Sheikh Abdullah and Kashmir, Muste showed that Scott’s nationalist sponsorship was not an isolated issue but one of many contentious political positions taken by the Brigade’s leadership.

In the end, pressure from the Indian press rather than the Brigade’s Asian Regional Council made Scott leave the march within its first week. Indian critics argued that Scott was using the cover of international peace politics to meddle in Indian domestic affairs.Footnote 50 This criticism had merit. While in Delhi planning the march, Scott was acting as a go-between between Angami Zapu Phizo, the Naga nationalist leader in exile, and Indian prime minister Nehru. Using Scott as a messenger, Phizo proposed to return to India in order to broker a ceasefire agreement between Naga nationalists and the Indian government.Footnote 51 Scott hoped that once the Naga “hostiles” (the term used by the Indian government for Naga nationalist insurgents) accepted a “Nagaland within the framework of the [Indian] constitution, … Phizo’s followers would run for office,” which would reintegrate them into Naga politics without violence.Footnote 52 Then, once the region had achieved peace for a transition period of approximately five years, a revision of the political status of Nagaland would be up for negotiation.Footnote 53 This plan provided a carrot for Naga nationalists to engage in peace politics, without stating the degree of autonomy or independence for Nagaland that might be up for debate in five years.

Nehru refused this proposal. Phizo’s offer as relayed by Scott would undermine Nehru’s own negotiations with the “moderate” Nagas, the new leadership of Nagaland, the proposed Indian state to be established in December 1963 within the Indian Union. According to Ed Lazar, writing from the road in the march’s first week of progress, there seemed to be “little hope for the Nagaland question” since the Indian government was planning an offensive against Naga nationalist insurgents involving 20,000–40,000 troops.Footnote 54

In Pursuit of Elusive Chinese Visas

From the start, the Indian and Chinese governments opposed elements of the Brigade’s wider politics in which the Friendship March was embedded. Certain Brigade leaders supported particular nationalist claims of states-in-waiting – specifically, JP for Tibetan claims against China and Scott for Naga claims against India. Therefore, ultimately China refused to give the marchers visas and the Indian press forced Scott off the march.

Although the marchers never received Chinese visas, they did spend six months walking across Northern and Northeast India. At first, they encountered significant local hostility. The government of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh considered putting them in prison for disturbing the peace, and they repeatedly met Hindu nationalist counter-demonstrators on their route.Footnote 55 When they reached Patna in JP’s native Indian state of Bihar, they drew large crowds for their public meetings, as well as positive news reporting.Footnote 56 However, the international-territorial aims of the march – providing a physical, human connection in the form of individual bodies between the capital cities of dueling nations – remained unfulfilled.

JP himself was a focal point for much of the controversy surrounding the march. While Western Brigade members might have perceived him and the Sarvodaya movement as too supportive of the Indian government, JP had many public Indian detractors. These critics were strongest among Hindu nationalists who vehemently rejected JP’s critique of Hindu nationalism as communalism and therefore as anti-national.Footnote 57 However, it was his support of an independent Tibet that created insurmountable international complications for the Brigade. Ed Lazar noted:

The presence of JP [on the March] highlighted the most complex question the group has faced thus far… JP had requested the government [of India] to recognize the Dalai Lama as the head of the émigré government in exile of Tibet. JP, as you know, feels that Tibet is an independent nation in which the Chinese have committed cultural genocide. At the time of Sino-Indian fighting JP called for the liberation of Tibet by the Indian army (he has retracted this particular plea now that the actual fighting has ceased).Footnote 58

JP’s support for international (and Indian) recognition of and liberation for Tibet compromised the third-party integrity and practical logistics of a march whose members needed visas from the Chinese government. JP believed that Tibet had never been Chinese and held that “the Tibetan people are as much entitled to freedom as the Indian people or the people of the Congo.” On the issue of negotiation over the contested India-China border, he argued, “It can only be private individuals and not States or their Officers who can be entrusted with arbitration.”Footnote 59 While Tibet was necessarily off the agenda for the Friendship March, which proclaimed impartiality between India and China, this issue hovered over JP’s and Indian Gandhians’ participation in the march, calling into question – at least to Chinese authorities – the march’s allegedly nonpartisan motives.

The Brigade tried to work through unofficial channels to procure their elusive Chinese visas. In particular, they hoped Ida Pruitt could facilitate this task.Footnote 60 Pruitt was the child of American Baptist missionaries. She was born and raised in China and worked with the Chinese resistance against the Japanese, eventually joining with Communist Chinese forces. Throughout her career, she was active in social work, social justice, and development circles.Footnote 61 According to A.J. Muste, she advised the Brigade that since “relations between China and India are ‘delicate,’” they should make it clear that there was “interest and support for the March outside India.”Footnote 62 She recommended that Muste should be sure to emphasize the Brigade’s general “anti-US militarism” stance.Footnote 63 In particular, she suggested that he reach out to the Chinese Peace Council – the Chinese branch of the World Peace Council, which was a Soviet Cominform “peace offensive” aimed at linking up with international peace and disarmament activists against US militarism.Footnote 64 Pruitt had been “invited to go to China as a guest of the Chinese government in 1959”; upon her return, US authorities confiscated her passport, deeming her a flight risk and a potentially dangerous conduit to Communist China.Footnote 65

While Pruitt was not able to procure visas for the Friendship March, she guided their submission materials and, like so many international advocates, endured some of the same visa/passport difficulties as those on whose behalf she worked. Her suggestion that Muste reach out to the Communist Peace Council – and Muste’s inability to take it up since it fell outside of his network of contacts – illuminated the presence of an international communist peace movement distinct from the Brigade community’s orbit.Footnote 66 The total separation between the Brigade community and their communist counterparts in the international peace movement made it hard for the Brigade to claim independence from Cold War politics, even as the Brigade believed itself to be neutral and apolitical – a feature of the Cold War trap.

After JP’s position on the Tibet question emerged as the sticking point for the denial of Chinese visas, Muste tried to pin down JP’s stance precisely: “The one thing [that] I am eager for now is to get from you … material relating to your own statements and activities in re[gards to] the Tibetan situation.”Footnote 67 Muste pressed JP on what exactly was the Tibet for which he advocated: “I recall your alluding to the setting up of a Tibetan government ‘in exile.’ Does this mean a conventional ‘government in exile’ which would be working toward violent change in the existing regime and engaged in subversion, sabotage etc. in pursuit of that objective?”Footnote 68

The question of whether violence could ever be a justified response to political injustice returned as contested ideological terrain for the Brigade. Ed Lazar wondered if a statement by the Brigade leadership – JP, Scott, and Muste – “on the attitude of the March towards the Sino-Indian dispute might be necessary and useful” for settling the Brigade’s internal debate between total pacifism and nonviolent interventionism.Footnote 69 Such a joint statement never emerged. It would have required Muste to get from JP “on the one hand, an accurate picture of positions he has taken and statements he may have made and, on the other hand, a clear idea about his present views and the kind of statement he is prepared to make” on the question of Tibet.Footnote 70 This clarity was not forthcoming.Footnote 71

With JP embroiled in politics over Tibet and Scott entangled in the Naga question, JP’s lieutenant Siddharaj Dhadda recommended that Muste handle the marchers’ route to China.Footnote 72 Looking for Pakistani or Burmese alternatives, Muste worked through Clarence Pickett, who was a close friend of Zafarullah Khan (a Pakistani, he was at that time the president of the UN General Assembly) as well as of the US ambassador to Burma.Footnote 73 Muste also pushed British Member of Parliament Fenner Brockway to advocate for the Brigade at the Far Eastern Desk at the British Colonial Office in order to facilitate possible passage to Hong Kong; so that, even if the march could not cross the Sino-Indian border, it could sail to Hong Kong and call attention to its aims in a liminal Chinese locale.Footnote 74

Though these efforts were futile, they showed the reach of the Brigade community into national governments and international institutional circles, illuminating the historical constellation of the international peace movement and the wider reaches of those sympathetic to it. Brockway had been the founding chair of War Resisters’ International (the Brigade’s parent organization) back in the 1920s; and Pickett, the executive secretary of the American Friends Service Committee from the same period. Brigade members attempted to operate through a web of transnational activism that had its roots in the interwar period. However, the structures of empire that had facilitated that activism (even anticolonial), in terms of travel and the ambiguity of border movement and regulations, no longer existed.

International versus National Civil Rights

Another factor that undermined the Friendship March was the competing demands for time and resources that other political justice projects placed upon the Brigade. While there was a strong American contingent on the Friendship March, key American members of the Brigade were absent because the Delhi-to-Peking Friendship March was not the most imperative piece of political justice activism for the United States in 1963. More urgent was the US civil rights movement’s March on Washington (scheduled for August 1963), planned by Brigade member Bayard Rustin (who had been central to setting up the Brigade’s Africa Freedom Action Project in Dar es Salaam during the winter of 1962). The presence of two ambitious marches on opposite sides of the world in the same year, both organized by Brigade members, highlighted the diffused attention of the Brigade community. Even as late as April 1963, Rustin was having difficulty getting leave from the War Resisters’ League to organize the US march, then billed as a prospective “Emancipation March on Washington for Jobs.”Footnote 75

In his refusal to release Rustin to focus on the US civil rights movement, Muste argued: “Civil rights, economic issues, including abolition of unemployment, and peace – are all one cause.”Footnote 76 As a way to justify the constraints on personnel, time, energy, focus, and resources under which he operated, Muste contended that all endeavors of the Brigade community fit within the same overarching mission. However, protests in Birmingham, Alabama, in May 1963 and the Kennedy administration’s decision to send a civil rights bill to the US Congress changed Muste’s political calculation; in June 1963 Rustin was able to turn his attention and efforts to organizing the March on Washington.

Muste’s initial hesitancy for Rustin to focus his total attention on US civil rights deserves further explanation. The bundling of various political justice causes (anticolonial nationalism, nuclear disarmament, US civil rights, minority rights) under the mantle of “international civil rights,” or “international political justice,” or the “international peace movement,” or indeed all three, formalized the connections – and the tensions – between the individuals who worked on these causes. The World Peace Brigade was an attempted instantiation of this bundling. These causes did not always align ideologically, and even when they did, they still bled time, energy, focus, and finances from each other. Yet this interwoven conglomeration of activisms – religious, labor, pacifist, etc. – was what allowed Rustin to build the March on Washington “out of nothing.”Footnote 77 Rustin captured this contradiction when he described the process of building consensus within this combustible arrangement that shared goals if not priorities: “Consensus does not mean that everybody agrees. It means that the person who disagrees must disagree so vigorously … that he is prepared to fight with everybody else.”Footnote 78

In the eyes of mainstream contemporary commentators, the March on Washington conferred conventional legitimacy on mass action and public protest.Footnote 79 The liberalist presentation of the marchers as a “gentle,” “polite,” “orderly,” “cordial,” “law-abiding” “army” aided this perception.Footnote 80 It was the first of many iconic marches on the US capital, creating the march on the center of the US federal government as a symbol for civil society mobilization that criticized the state. In contrast, the Friendship March passed through a region that had been made into a political periphery by war and postcolonial state-making, and marked the demise of the World Peace Brigade as an organ of the international peace movement.

Both marches were ambitious endeavors, but they were exact opposites in scale, duration, distance, focus, participation, and outcome. The March on Washington was a national, single-day event with approximately 250,000 participants who converged on the Washington Mall for a series of speeches by US civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King. The Friendship March was an international six-month endeavor by nineteen walkers who crossed nearly 3,000 kilometers of territory, engaging with local populations by leading nonviolent civil-disobedience workshops in Gandhian ashrams en route. Political change is not easy at any scale, but the Brigade’s dream of escaping national allegiances made its transnational activism an even more fraught enterprise than that of its American cousin.

The conceptual divisions between nationalist claims-making and transnational advocacy that emerged within the planning and execution of the Friendship March exacerbated the Brigade’s interpersonal tensions. In May 1963, frustrated by the divergence between the Brigade’s activism and his own projects, Scott floated his resignation from the entire organization, not just the march: “Unless the whole scope and concept of the World Peace Brigade can be changed I cannot continue to act as Chairman.”Footnote 81 He still believed in the need for some “kind of an international [peace] force,” though he made an illuminating typo, mis-writing “peace” force as “police” force. Scott followed “with intense interest” the “immensely significant … developments in [the American] South,” searching them for the “lessons” they might “imply for the situation confronting us in Southern Africa.” Looking for the common thread, he still pinned his hopes on a peace force to force peace. “Organized separately from the UN itself,” it would address the political justice questions of disenfranchised peoples within independent states, which the UN was not equipped to handle.Footnote 82 Scott searched for but did not find the organizational and analytical forms that would combine the political justice questions of US civil rights, apartheid Southern Africa, and minority issues in India. The World Peace Brigade could not provide the vehicle he sought. It did not successfully formalize the transnational advocacy of its leaders and members because the issues at play – nationalist claims-making (support for those demanding sovereignty) and civil or minority rights within states (limits on state sovereignty) – could not be bound together.

Muste responded that it was not the Brigade that had failed Scott but, rather, Scott who had failed the Brigade. “The Naga matter was not one which the World Peace Brigade undertook,” he said to Scott, adding that Scott’s “preoccupation” with the Nagas “was a distinct disadvantage to the March.”Footnote 83 There were also “quite fundamental differences in the thinking of yourself and some of the rest of us about the nature” of the Brigade, that it should even be in the business of advocacy on behalf of nationalist claimants.Footnote 84 Muste’s riposte to Scott’s ruminations – and his refusal to accept Scott’s resignation – replayed Muste’s annoyance with what he considered to be Scott’s abandonment of the Africa Freedom Action Project in Dar es Salaam the previous year. He closed his letter with another, more tactful reason for the Brigade’s failings – political timing: what “the situation would now be if … the Kaunda freedom march had taken place, if the Sino Indian conflict had not erupted, would be difficult to say.”Footnote 85 While the early 1960s had seemed to be an opportune moment for the Brigade’s mission, events had overtaken them.

The same month as Scott’s threatened resignation, JP also offered to resign from the Brigade, did resign, and then withdrew his resignation. This was a pattern for him. Charlie Walker, one of the Brigade’s US marchers, wrote to Muste in May 1963: “JP ‘resigned’ from a number of organizations, partly because he did not wish to embarrass them, partly because he wished to be free to speak his mind, and in the case of [the Brigade] for both reasons plus the criticism from the Westerners.”Footnote 86 Alluding to Muste’s aggressive attempts to pin him down on Tibet, JP found this mode of criticism, particularly its “harsh” and “cross-examining” manner, disrespectful.Footnote 87 According to Walker, Julius Nyerere (a Tanganyikan anticolonial nationalist leader and, at that time, president of Tanganyika) also had difficulties with JP “on his work in East Africa” the previous year, 1962. These obstacles involved JP’s pattern of making certain statements that could be easily misconstrued, of not providing specifics about these statements, and of using the resulting tumult as a justification for withdrawing when it did not seem that the shared endeavor would succeed.Footnote 88 Of the “big three” in the Brigade – JP, Muste, and Scott – JP was the most circumspect about what he left behind on paper regarding their internal disagreements, allowing him to portray himself as a bystander of interpersonal conflict rather than a direct participant. Scott and Muste’s disagreements about the Brigade’s role on the march, therefore, need to be read against the grain since they were a triangular conversation in which JP played a featured, if self-muffled, role.

According to Muste, it was the “injection” of the Naga question and Scott’s “insistence” on advocating for Naga independence that fractured unity between Indian and Western marchers.Footnote 89 Suresh Ram considered Scott’s 1963 attempt to bring the Naga claim to the United Nations “a painful surprise.”Footnote 90 For Muste, the Brigade “had clearly taken the position that the Naga matter could not be injected into the March,” but Scott “could not give [it] up … [otherwise, he] would have been an extremely valuable asset.”Footnote 91 Muste wondered whether, if Scott had prioritized the endeavor, the march would have been able to procure its elusive Chinese visas. However, Muste said, the Brigade’s “experience in Africa, as well as India,” showed that Scott “is not capable of this” single-minded focus. He continued: “In a certain sense, this is his strength; but it also creates serious problems.”Footnote 92 What worked for an individual did not hold for an organization.

Scott’s rebelliousness – his addition of an Indian minority or civil rights concern into an international peace project – upset a delicate equilibrium. The Brigade saw itself as internationally apolitical, unallied with the interests of state power. It called into question the impenetrableness of national borders by attempting to cross them physically, and it deprioritized national security concerns by finding violence, state-sanctioned or otherwise, invalid. Yet the Brigade also respected tricky domestic political terrain, refusing to “inject” contentious political questions into – and seeing them as a distraction from – its transnational mission. There was also a tactical consideration to the Brigade’s annoyance with Scott’s Naga advocacy: in reality, he made it more difficult for Indian Gandhians to work behind the scenes on the Naga issue.Footnote 93

Back in the United States, Bayard Rustin was “almost contemptuous” toward “these anarchistic people who will not do what they are told” because they were “apolitical” purists.Footnote 94 He had found some of the Brigade’s endeavors, particularly in decolonizing Africa, “enormously worthwhile precisely because [they were not] just a kind of pacifist bearing witness [but] linked up with a major anticolonial movement.” In an Indian context, however, he felt that the Brigade’s remaining separate from minority-rights issues cast doubt on its support for matters of political injustice within the state – something of deep concern for a US civil rights activist.

Scott was not the only leader of the Brigade who thought that the organization might eventually take up the question of Nagaland. According to a letter from Charlie Walker to Muste, JP himself “was considering some specialized role for a few key people in regards [to] the Naga question.”Footnote 95 In conversations with Narayan Desai (an Indian member of the Brigade) in Patna in August 1963, the letter continued, JP “concluded this was a job for a highly skilled person or persons who understood both conventional political dynamics and had the imagination and ability to relate nonviolence to specific issues and choices arising within that context.”Footnote 96 Perhaps this proposed Naga peace project could be modeled on “the role Bayard [Rustin]” and Muste “played in East Africa” during the Brigade’s Africa Freedom Action Project. “The obvious difficulty is, as JP and [Narayan Desai] observed, such people are scarce and they are always needed where they already are.”Footnote 97 On the one hand, the Brigade community lacked enough “great men” to tackle all the interwoven political questions it sought to address. On the other, its individual leaders’ many causes and interests undermined the Brigade’s own activities. The Brigade community itself did not see an incompatibility. From its perspective, Scott’s advocacy for Nagaland (in India) and JP’s for Tibet (in China) proved that the Brigade was not aligned with either country. However, that was not the point of view of either the Indian or the Chinese government.

Conclusion

As a practical matter, the Friendship March failed to have much measurable impact improving Sino-Indian relations, its primary goal. It never managed to get entry visas from China. Without travel documents, the marchers had to halt in Ledo, Assam, in January 1964. Yet the World Peace Brigade’s “parts” – the individuals who composed the organization – were more significant than the whole. They were international Gandhian peace workers, soldiers in a global peace brigade, and their aim was political transformation: of norms (of war and peace), of definitions (of “state” and “non-state”), and of categories (of “national” and “international”). Their walk across North and Northeast India changed the international peace movement but not in the manner that they had hoped and anticipated. It was an end of the World Peace Brigade, rather than a beginning of further global intervention. The Brigade had “proved too grandiose in its ambitions, too lacking in resources and too reliant on key personalities in the USA and India (who had many other demands on their time).”Footnote 98 According to Muste, its leadership in India, the United States, and Britain were “separated by immense distances, … one of the chief reasons for its difficulties.”Footnote 99

War Resisters’ International, the Brigade’s parent organization, blamed the latter’s demise on a mismanagement of political scales: the Brigade had imposed “an international structure” instead of allowing its activities to grow from the local to the national level and then to the international. Brigade members had “been projected into alien situations without adequate preparation.”Footnote 100

While one difficulty of the Brigade’s Africa Freedom Action Project in Dar es Salaam had been that it was not an African project, Ed Lazar, who stayed on the Freedom March for its full duration, thought that the fatal flaw of the Friendship March was that it became an Indian endeavor rather than an international one.Footnote 101 The Friendship March showed that an enterprise dominated by Brigade members who were Indians on a march through India could still walk into a set of difficulties – those caused not by their being “alien” to the country but by the collision between transnational advocacy and state sovereignty.

The theme of conflict between scales of political power – national, regional, international, local – enveloped Brigade activities. Advocacy worked between these scales, facilitating the movement of nationalist claims through international politics.Footnote 102 Advocates could operate at the interstices of these scales as individuals, personally, privately, and incrementally.Footnote 103 Navigating scales required long-term, in-depth, interconnected work of the sort that JP, Muste, and Scott had significant experience as individuals; in an organization, however, they foundered. Their inability to work together is of less surprise than that they came together in the first place, as the Brigade was a collection of outsized individuals whose causes competed for focus and funding.

The World Peace Brigade was misnamed: it did not represent the world, was not particularly peaceful, and lacked the cohesion and size of a military brigade. Its parts – the experience, passion, and work of A. J. Muste, Jayaprakash Narayan, Bayard Rustin, and Michael Scott, among others – were greater than its whole. The Brigade was an “army of generals not an army of soldiers.”Footnote 104 The history of the Brigade’s Delhi-to-Peking Friendship March became a narrative of internal organizational divisions around the issues of nationalist insurgency in India and China and the legitimacy of Indian state violence during the Sino-Indian War – questions that had a degree of geographical overlap with each other and with the march’s route across North and Northeast India.

These internal and external conflicts illuminated the mismatch between the Brigade’s aims and operations. In the words of April Carter, a member of the Brigade community who had friends and colleagues on the march, the World Peace Brigade “illustrated the pitfalls … of an international group publicly challenging nationalist sentiments” on questions of national security.Footnote 105 It was a transnational, apolitical organization, whose leadership held defined national-political stances and who functioned most efficiently outside of the organization. The Brigade sank under the weight of these contradictions – between transnational advocacy and state sovereignty, between the individual versus the organization – which had been visible since its Africa Freedom Action Project in Dar es Salaam.

The Brigade’s lifecycle – active from 1961 to 1964, officially dissolved in 1966 – reflected the diminution of its wider community’s international advocacy on behalf of nationalist claimants as the accelerated decolonization of the early 1960s slowed.Footnote 106 (Emblematically, Muste died in February 1967, following his deportation from South Vietnam, as he attempted to negotiate between sides during the US war in Southeast Asia.) However, before the dissolution of this network of advocacy that worked to facilitate nationalist claims-making, JP and Scott had a concluding joint mission: a final journey to Northeast India to forge peace in Nagaland.

The individual tensions within the Brigade exposed and fed the contradictions between transnational advocacy and state sovereignty. The frictions on view during the Friendship March – between Western and Indian Brigade members, between the purpose of the march and JP’s advocacy for Tibet as well as Scott’s for Nagaland; and even, to a lesser degree, between Muste and Rustin concerning the morality and politics of focusing only on US civil rights – illuminated the fissures within the Brigade as a political project. These divisions were not only personal, they were also analytic, since they were symptoms of competing political priorities. They articulated the struggle to make transnational advocacy compatible with state sovereignty when these ideas operated on two different scales of political geography:Footnote 107 the first, crossing (and questioning) national boundaries as well as those within the state by supporting minority nationalisms; the second, shoring up the political unit (and unity) of the state.Footnote 108

The Friendship March – the World Peace Brigade’s attempt to walk from India to China in order to promote peace between those countries – halted in Ledo, Assam, India, in January 1964. Because elements of the march’s leadership supported nationalist movements within those two countries, China would not grant visas to allow the march to cross the border and the Indian government grew increasingly hostile toward the endeavor. Three weeks later and 300 kilometers from where the march ended, the Nagaland Baptist Church Council held a convention in Wokha, Nagaland, “crying in the wilderness for peace.”Footnote 1 Led by the missionary Reverend Longri Ao, nicknamed the “Naga Prophet,” the Council chose two of the World Peace Brigade’s leaders – Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) and Reverend Michael Scott – along with the chief minister of Assam, Bimala Prasad Chaliha, to head a peace mission with the purpose of arbitrating between the Indian government and Naga nationalist insurgents in Northeast India.Footnote 2 The Peace Mission hoped to establish a platform of mutual trust from which peace could grow. However, “peace” did not correspond with “independence” – a distinction that echoed the divergence between the aims of nationalist insurgent claimants and their transnational advocates.

That year, 1964, was not the first time the Naga Baptist Church had mediated between nationalist insurgency and Indian rule. In 1963, Scott had kept Reverend Ao abreast of his negotiations between Naga nationalists and Indian prime minister Nehru during the Friendship March; and a Naga Hills Ministers Peace Mission had taken place in the 1950s.Footnote 3 This latest effort, the 1964 Nagaland Peace Mission, was a civil society endeavor – made up of unofficial (i.e., Chaliha was not acting in his official capacity as Assam’s chief minister), allegedly unaffiliated, volunteers – that sought to reconcile the question of Nagaland’s political shape within, or alongside, that of India’s.

Negotiations under the auspices of a civil society mission that did not officially represent either a nationalist movement or a state government seemed safely apolitical. However, the transnational network in which JP and Scott were key members was integrated into official government as well as international institutional circles of power and affiliated with a number of sometimes overlapping, sometimes contradictory movements and interests. JP and Scott were far from politically disinterested free agents – and the web of political causes that bound them extended to the Peace Mission.

Sovereignty on the Edge

The Nagaland Peace Mission was a site for fashioning postcolonial state sovereignty in a classic borderland, a former edge of empire, a “neo-colonial” hinterland.Footnote 4 Sovereignty is the international recognition of – and the totalizing control over – the zone of national self-determination, the political narrative that clothes power with legitimacy. Placement in a “periphery’s periphery” – in a region lightly connected to its governing capital as well as to global centers of power or governance – intensified claims of self-determination predicated on minority difference while attenuating the path of these claims to international forums. Nagaland’s physical distance from New Delhi provided intellectual space for advocates who worked to reconcile Naga self-determination with Indian sovereignty. JP, Scott, and Chaliha had experience grappling with the process of constructing sovereignty for postcolonial states and nationalist movements claiming that status. They, and others who took part in the Peace Mission, found in the end that Indian sovereignty and Naga self-determination were a call and response: they were distinct political ideas, articulated by different parties; each was a direct commentary upon and a repudiation of the other.Footnote 5

Before examining the Peace Mission and its powerbrokers, it is important to note a subject that is not centered in this narrative: factionalization within the Naga nationalist movement. The Naga nationalist leader Angami Zapu Phizo had left Nagaland in the late 1950s not only to gain international attention for the cause of Naga independence but also because he was losing control over the nationalist movement as some Nagas sought to strike a deal with New Delhi. By remaining in exile; Phizo was able to maintain symbolic leadership because he did not tarnish his authority by compromising with India; yet exile meant that he could not control the Naga nationalist insurgent movement on the ground. Each Naga negotiation with New Delhi, past and present, has created parties who signed off on negotiations and those who refused to do so, fracturing the Naga nationalist movement. Since these fissures often occurred along tribal lines, they were used by the Indian government to undermine the legitimacy of a Naga nation within a tribal society.Footnote 6 Choosing at which scale to locate a political question – national, international, regional, local, even tribal – is itself an argument as well as a matter of power relationships.Footnote 7 The Indian government has had a vested interest in defining Nagas as a set of tribal peoples rather than a nation and the Naga claim as a domestic or regional concern rather than an international one – while Phizo, along with Scott, placed the Naga struggle within an international frame.

Situating the Naga claim of independence within the worldwide politics of decolonization explores global state-making processes outside the frame of the postcolonial state, by shifting focus from decolonization’s promise to its limits, from its liberations to its oppressions. Yet, without nuance, critiques of postcolonial state sovereignty can slip into imperial nostalgia. Indeed, the networks that connected Nagas to international politics were imperial remnants, linked to the region through the legacies of colonial rule and missionary conversion. The primacy placed on advocates such as JP and Scott as interlocutors between nationalist movements and state governments reflected hierarchies of power within an international system being rearranged, rather than redistributed, by decolonization.Footnote 8 Their role also demonstrated the weakness of the Naga claim: that it remained the purview of unofficial advocates rather than of the United Nations.

Decolonization led to the triumph of certain nationalist claimants over others, of an India over a Nagaland. Over time, the “victors” have dominated narratives of colonies-turned-states, shaping who has received a “national” history of their independence struggle. In consequence, the narratives of those excluded from new state governments and positions of influence became local or regional rather than national or international. Yet, these historical actors continued their international activities in a variety of forms that worked around or challenged states – through civil society organizations or insurgent movements, or both. The histories of states-in-waiting and of those left behind by decolonization – both nationalists and their advocates – requires recognition that they were political and moral actors who sought liberation but were unable to delink themselves from the oppressions, past and present, that functioned as constraints.

The Politics of Reconciliation

The Naga Church was an entity that transcended the national scale of India and the regional context in which the church was embedded, because of its own global connections drawn from the history of missionary activity in the Indian Northeast. It was also the most powerful civil society organization in the region, maintaining an ambivalent relationship with the Indian government, which had worked to sever the church’s ties to the United States by constraining American missionary activity. New Delhi forced the “indigenization” – the term used by American Baptists for the training and empowering of indigenous Christians to take on church leadership positions – of the Baptist Church in Northeast India decades earlier than American Baptists chose to shift leadership positions in Burma, Congo, South India, and elsewhere to people from the community in which they served.Footnote 9 Indigenization ran parallel to decolonization and was itself an attempt to manage the forms that decolonization might take.

Missionaries from the United States portrayed themselves as bastions of Western/First World civilization threatened by decolonization and Cold War crises. Gerald Weaver, an American Baptist missionary serving in Congo during the Congo Crisis in the early 1960s considered himself part of the anticommunist vanguard in the decolonizing world. As he wrote in 1961, for those “on the outside of the Unites States looking in, it seems so much easier to see that we have talked away one previous Western stronghold after another and the Communists have reaped the benefits.”Footnote 10 This perspective aligned neatly with the domino theory of communist expansion and concern with American failure to adequately combat it, espoused by US administrations from Eisenhower to Reagan and employed by settler-colonial regimes in Southern Africa to justify their opposition to decolonization.Footnote 11 It displayed the anticommunist frame in which American Baptist missionaries saw decolonization, a frame that the Naga Baptist Church also used.

Kijungluba Ao, a Naga Baptist leader who would receive the Dahlberg Peace Award from the American Baptist Convention and the Padma Shri Award from the Indian government, worried that Nagas were not “very far from the dangerous disease” of communism due to the fact that the departure of foreign missionaries was “weakening our united effort to witness for Christ.”Footnote 12 Additionally, this was a pitch for money from the United States to support the Naga Church. He also said that Naga Baptists were “a community of people who were sophisticated enough to know their responsibility” – responsibility to God and responsibility to peace.Footnote 13

Nagas saw themselves as sophisticated, civilized, and Westernized. Christian identity, connected to an increasingly politically conservative American religious denomination, was of crucial importance for Naga nationalists as well as for the Naga Baptist Church. “Nagaland for Christ!” was (and remains) a popular nationalist insurgent rallying cry. It also meant that appeals to atheist Communist China had the potential to undermine the legitimacy of the Naga nationalist movement.Footnote 14 “Maoist” as a pejorative adjective, with its atheist/authoritarian connotations, has been and continues to be a label placed on Naga nationalists by their opponents.Footnote 15 Most importantly for JP on the Peace Mission, Christian identity meant that an Indian Union that included Nagaland on equal footing with its other constituent parts had to have room in its conception of India to contain a non–Hindu-majority Indian state alongside Kashmir.Footnote 16

The Nagaland Baptist Church Council organized the Peace Mission. After choosing its members for the mission, the Church Council set up a negotiating committee of Naga leaders, which included themselves, family members of Phizo, and the Federal Government of Nagaland, which was the dominant Naga nationalist insurgent movement in the region during this period. The church council also reached out to the Indian government, which formed its own negotiating committee under the leadership of Foreign Secretary Y. D. Gundevia.

These two committees then agreed to the Church Council’s selection of the Nagaland Peace Mission: Chaliha (Assam’s chief minister), JP, and Scott. This choice was not accidental; it mirrored internal World Peace Brigade proposals.Footnote 17 All three men had been active in nonviolent anticolonial nationalist resistance – JP and Chaliha for Indian independence; Scott against South African apartheid and rule over South West Africa; and both JP and Scott in the 1962 Africa Freedom Action Project in Dar es Salaam to support African liberation struggles and in the 1963 Friendship March. At the Peace Mission, Chaliha represented the regional context of the Indian Northeast; and Scott, the potential of international intervention. JP brought his status as an outsider to Indian electoral politics as well as his moral authority as a Gandhian. He hoped to speak for the idea of an Indian Union rather than for the government of India, since he did not align “state” and “nation” in his conception of Indian sovereignty, citing Gandhi for ideological backing: “Gandhiji was clear in his mind that the State could never be the sole instrument for creating the India of his dreams.”Footnote 18

The Indian government saw the Indo-Naga state-versus-nation conflict as an example of the relationship between tribal peoples and the Indian government.Footnote 19 According to Gundevia, the government’s top representative in the Peace Mission talks, Indians and Nagas did not live, and had never lived, “as two nations side by side.”Footnote 20 He argued that Nagas were not a nation but a tribal people, defined in that manner in the Indian constitution as part of the 1960 negotiations for the creation of an Indian state of Nagaland.Footnote 21 In Gundevia’s formulation, this status did not make Nagas unique, since there were constitutionally defined tribes “right in the Centre of India” with the same “peculiar social set-up.”Footnote 22 As a tribe, the Nagas already had a form of “protected autonomy”; however, this was itself a contradictory notion: if autonomy needed to be protected, were a people functionally autonomous?

Gundevia reasoned that historically the territory of “Nagaland was a part and parcel of India.”Footnote 23 Therefore, the creation of an independent Naga state would break with this history and involve changing Indian national boundaries, which was out of the question. “Boundaries are drawn slowly and we cannot redraw the boundaries unless after a war.”Footnote 24 As a part of British India, Nagaland was therefore part of independent India.

Decolonization did not usually seek to alter colonial boundaries (with, in Gundevia’s formulation, the important exception of the partitions of Pakistan and India in 1947 and their bloody aftermaths); rather, it enshrined them. According to Gundevia, while a “certain section of the people of Nagaland want a Sovereign State,” this did not apply to all Nagas, certainly not those in the government of, and receiving salaries from, the Indian state of Nagaland. Therefore, he wanted to know “what is meant by an independent Sovereign State” when that demand did not include all Nagas, when Nagas were not a nation but a tribal people, when tribes already had particular and varying degrees of autonomy within India. In summation, Gundevia argued: British India had historically included Nagaland. Colonial boundaries were inherited by the postcolonial state and were not to be redrawn short of war, which was an activity that occurred between two (or more) sovereign states, such as India and China, and did not include India’s counterinsurgency operations against Naga insurgents.Footnote 25

For Naga nationalists in-country (the Federal Government of Nagaland, aka the “government-in-waiting” of Phizo’s group of hardline nationalists), an “independent sovereign state” meant just that: an autonomous, self-governing sovereign state with international-legal sovereignty – a status that, for the Nagas, would have to be achieved through external recognition and intervention since Naga nationalist insurgents did not occupy all of the territory they claimed, as nationalist conceptions of Nagaland included regions outside of the Federal Government’s military control. To gain sovereignty, in the form of both external recognition and internal territorial dominance, they needed international oversight, and they did not fully trust either the Baptist Church Council or members of the Peace Mission to help them achieve such control. The Federal Government wanted peace talks “under the witness of the United Nations,” and those talks needed to be between themselves and the government of India alone. They felt that the government of the Indian state of Nagaland, created in 1963 by constitutional amendment after Nehru’s negotiations with “moderate” Nagas in 1960, should not be at the negotiating table. “No political solutions can be done under the initiative of this false state.”Footnote 26

In a manner similar to other peoples’ demanding independence, the Federal Government threatened to turn to the communist world for support: “If the UN, the supreme organization of the day, is not in a position to execute its sacred charter towards the Nagas, the Nagas are strongly prepared to take aid from any quarter.”Footnote 27 Here, Naga nationalists signaled the prospect of aid from Communist China and thus of a Southern-Asian Cold War front. Despite the little aid that Naga nationalists received from China during this period, this was no idle threat to India, who had lost a war with China two years prior, at which time the Chinese had voluntarily halted less than 300 kilometers away from the Naga Hills.

Another option the Federal Government of Nagaland proposed was that the “World Council of Churches sends a Fact Finding Commission.”Footnote 28 The World Council of Churches had held its Third International Assembly in New Delhi in 1961, coinciding in time and place with the meeting of the Institute of Comparative Constitutional Law. The Nagaland Baptist Church Council sent a delegation to the Assembly, led by Longri Ao.Footnote 29 Many of the British lawyers who wrote the constitutions for decolonizing British African colonies and were friends of the Brigade community informally attended the Assembly, as well, and formally attended the institute’s meeting.Footnote 30 The keynote address at the Delhi Assembly featured a critique of unrestrained state sovereignty. It proposed international-legal structures as an alternative, asking states to submit to the “jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice” and other “international regulations.”Footnote 31

Religion and law are distinct realms, and international law and comparative constitutional law are separate fields; yet the intersection between personnel, time, and location of these two gatherings highlighted the overlapping circles of people who inhabited these multiple spheres. Nearly all the organizations and individuals whom nationalists called upon to support their claims against empires and postimperial formations were in search of an alternative universalism to state sovereignty.Footnote 32 However, what these advocates proposed – bounded sovereignty and non-national vehicles for self-determination – contradicted the aims of the nationalists who hoped that the intervention of advocates would help enable their states-in-waiting to gain full national independence. At the same time, it made sense, based on the World Council of Churches’ critique of state sovereignty in New Delhi a few years previously, that Naga nationalists might see that organization as a potential sympathetic intermediary.

“the Nagaland Drama”Footnote 33

While Naga nationalists reached out to, and sought to work with, a range of nongovernmental organizations and unofficial individuals to negotiate on their behalf with the Indian government, they doubted that many of these intermediaries fully grasped the dire situation in their region. The Federal Government of Nagaland had accused the Nagaland Baptist Church Council of cowardice in its previous dealings with New Delhi, and resented the phrase “peace-talk,” seeing it as cheap talk when, according to Scato Swu, the president of the Federal Government, Naga “rights are denied.”Footnote 34 Scato continued, “Peace-talk [also] clearly implies a political settlement, and we [are] only prepared to have a direct talk between the Government of India and the Federal Government of Nagaland, after declaring [an] effective ceasefire.”Footnote 35 They claimed that the military assistance that the Indian government was allegedly receiving from the United States and the UK after the 1962 Sino-Indian War was in reality being used to fight Naga nationalists.Footnote 36

Media and reporting, that is, narrative dissemination for external audiences, was a battleground between nationalists and their ruling authorities. While India controlled almost all news reporting on Nagaland, Naga nationalists closely followed international media. A few days after Scato Swu heard a Radio News report, the Lima (Peru) Football Disaster in which a referee’s controversial call led to the death and injury of 800 people, he compared the members of the Peace Mission to referees in a football match, reminding them of the bloody stakes of their responsibility.Footnote 37 Scato’s analogy to an event that had occurred on the other side of the world three days earlier showed how closely even insurgents living in the jungle followed international currents.Footnote 38 Scato also warned Scott that he was getting misleading information from Phizo (in exile in London) and Shilu Ao (chief minister of the Indian State of Nagaland), and instead needed to be in direct contact with the Federal Government of Nagaland.Footnote 39 Though they lived under martial law as well as under a media and travel ban, Naga nationalists in Nagaland paid attention to the world they sought to invite in to recognize them.