Introduction

Singlish, also known as Colloquial Singapore English (CSE), is a heteroglossic assemblage of English, Malay, Mandarin, and Chinese dialects with origins in the southeastern provinces of China, in particular Hokkien. This article is interested in Singlish as it is rhetorically delivered in metadiscursive writing. It examines in particular how Singlish has come to be enregistered (Agha Reference Agha2003, Reference Agha2007), that is, transformed from an unmarked vernacular into a stylised register. In focus here is the performative and subversive value of the register in question: just as social styles can be activated through ‘creative, design-oriented processes’ in talk (Coupland Reference Coupland2007:3), so Singlish-as-style (Wee Reference Wee, Mathews and Fong2016) can be mobilised in texts to creative as well as critical ends.

The theoretical question for us is not merely how a vernacular like Singlish is enregistered to index mundane locality, but also the ethical implication of such enregisterment. That is, when Singlish is performed as ‘a highly reflexive mode of communication’ (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:73) with a view to critiquing the perceived hegemony of Standard English, does it not eventually become something other than itself? As I demonstrate below, while Singlish is weaponised on the basis of its egalitarian associations, its fetishisation into a creative-critical register by Singaporean intellectuals turns it into an elitist language full of cunning manoeuvres and rhetorical flourishes.

At issue here is a question of voice: when monolectal speakers of a vernacular language are represented by their more educated counterparts who can switch between vernacular and standard registers at ease, the former slips into the subaltern: ‘spoken for, spoken about, but never directly speaking’ (Wee Reference Wee2018:109). And the vernacular that is purportedly celebrated, when mobilised at the scale of creative and metadiscursive writing, can paradoxically become inaccessible to its lay speakers. Such is the ethical dilemma that arises when a marginalised variety is articulated beyond its immediate indexical order in pursuit of politico-ideological work.

Singlish as a problem

The enregisterment of Singlish is premised on its being marginalised by the language establishment in Singapore. As enshrined in Article 153A of the Singapore Constitution, Malay, Mandarin, Tamil, and English are instituted as the four official languages of Singapore. This quadrilingual constellation is deeply entrenched in top-down discourses and public writing (see Lee Reference Lee2020). It defines the official dimension of the linguistic landscape to the exclusion of several other spoken languages, notably the Chinese dialects (mainly Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, and Hainanese) and Singlish.

The Chinese dialects have been in gradual decline since the late 1970s, owing in part to the Speak Mandarin Campaign (SMC), conducted annually to promote the use of Mandarin at the expense of the dialects. The SMC finds its counterpart in the Speak Good English Movement (SGEM), launched on 29 April 2000. Just as the SMC sets out to marginalise the Chinese dialects, so the SGEM aims at streamlining English usage with a mandate to eradicate Singlish. The inaugural mission statement of the SGEM was ‘to encourage Singaporeans to speak grammatically correct English that is universally understood’ and ‘to help Singaporeans move away from the use of Singlish’ (cited in Lim Reference Lim2015:264). More recently, this anti-Singlish rhetoric has been slightly attenuated; the SGEM's revised (and current) mission statement states that it ‘recognises the existence of Singlish as a cultural marker for many Singaporeans’, which can be taken as a mild concession from its previous stance. Notwithstanding this softening in tone, the SGEM still projects a strongly didactic character. It stresses the importance of ‘understand[ing] the differences in Standard English, broken English and Singlish’, and tasks itself to help ‘those who habitually use fractured, ungrammatical English to use grammatical English’ as well as ‘those who speak only Singlish, and those who think Singlish is English, to speak Standard English’.Footnote 1 As an official platform, the SGEM unequivocally establishes Standard English as the benchmark of correct usage, thereby stigmatising Singlish as a non-legitimate medium.

It is against such systematic disenfranchisement that Singlish has come to be iconised into a register for cynical resistance and discursive activism against patriarchal structures, as represented by the SMC and the SGEM. In response to the taylorist language regime that privileges Standard English, a vernacular modality of writing has shaped up in which Singlish (incorporating the Chinese dialects) is fetishised as an exclusive signifier of an egalitarian, heartlander ethos and commodified for popular reading. Initiatives that have taken up Singlish along these lines include theatrical projects engaged in ‘highly reflexive deliberations’ about Singlish (see Wee Reference Wee2018:127), the now defunct anti-establishment website TalkingCock.com (with its flagship publication The Coxford Singlish Dictionary), and the Facebook-based Speak Good Singlish Movement (SGSM), conceived as an antagonistic counter-movement to the SGEM. Going against the grain of language policy, these practices eschew all political correctness with regard to language usage and indulge in the heteroglossic carnivalesque of multilingualism from below.

These practices point to the evolution of Singlish into a stable register capable of being commodified to perform identity work. Following Schneider's (Reference Schneider2003) Dynamic Model of World Englishes, Singlish can be said to have attained endonormative stabilisation (Phase 4 in Schneider's model), at which point the ‘psychological independence and the acceptance of a new, indigenous identity result in the acceptance of local forms of English as a means of expression of that new identity’ (Schneider Reference Schneider2003:250). On this view, creative-critical expressions of Singlish-based identities indicate a high degree of linguistic autonomy and self-confidence (Schneider Reference Schneider2003:252, Reference Schneider2007:289)—a characteristic trait of postcolonial Englishes at a mature stage of development.

The commodification of Singlish on highly articulate platforms throws up another set of questions. Who uses Singlish, and at which register? Who speaks up for Singlish? Generally speaking, two groups of Singlish users can be identified (Wee Reference Wee, Mathews and Fong2016:49, Reference Wee2018:15, 58, 85). The one group comprises monolectal Singlish users who have little or no access to a comprehensive repertoire of Standard English due to, inter alia, relative lack of education. The other group consists of highly educated individuals, including what Wee (Reference Wee2018:101) calls Singlitteratti, ‘a relatively closed circle of well-educated creative and artistic individuals who enjoy playing around with Singlish words and phrases and are keen to promote Singlish’. These are users who have the capacity to switch easily between Singlish and Standard English, and are hence able to deploy linguistic features conventionally associated with Singlish for identity work on metadiscursive scales, namely to critique language policies in defence of the vernacular. As my case study illustrates, it is these educated users who represent their less educated counterparts in intellectual discourses on Singlish, but in the course of doing so, they tend to twist Singlish into a rhetorically elaborate version of the street parole.

Spiaking Singlish: The ludification of English

My case in point is Gwee Li Sui's Reference Gwee2018 book, Spiaking Singlish: A companion to how Singaporeans communicate, which traces a lineage of counter-discourses emerging in response to state-imposed constraints on the vernaculars. A former professor specialising in pre-modern English literature as well as a poet and graphic designer, Gwee is one of the most outspoken advocates and practitioners of Singlish. In his 2015 TED talk entitled ‘Singlish is a language for our future, lah!’,Footnote 2 he openly pronounced Singlish a futuristic, global, and ‘people-powered’ language, subverting the official narrative that constructs Singlish as subterranean and non-cosmopolitan. This stance also finds expression in Gwee's own poetry, which makes liberal use of Singlish. All of this qualifies Gwee as a representative of Singlitterati.

Spiaking Singlish, a playful, metalinguistic primer dedicated to Singlish, culminates from Gwee's longstanding efforts in rebranding Singlish through his column writings in the controversial sociopolitical website ‘The middle ground’ (now defunct). Marketing itself as ‘possibly the first book on Singlish written entirely in Singlish’,Footnote 3 Spiaking Singlish flaunts its performativity in the main title: spiaking is the Singlish variant on ‘speaking’ in exaggerated mimicry of the way the word is presumably pronounced by Singaporeans. Whether such a pronunciation is empirically attested is quite beside the point; it is the oral-aural slippage between the received and parodied pronunciations that is the source of earthy humour. In terms of genre, Spiaking Singlish is a cross between a popular expository text and a Lonely-Planet-style guide meant to make a curiosity out of Singlish. As a blurb on the publisher's website suggests, Singlish is positioned here as a styling resource.

Spiaking Singlish doesn't just describe Singlish elements… Rather, it aims to show how Singlish can be used in a confident and stylish way to communicate. Gwee Li Sui's collection of highly entertaining articles shares his observation of how Singlish has evolved over the decades. To appeal to the ‘kiasu’ nature of readers, each of the 45 pieces comes with a bonus comic strip. There is also a Singlish quiz at the end of the book for readers to test their grasp of Singlish!Footnote 4 (emphasis added)

The motivation behind Gwee's companion is therefore non-pedagogical; its primary intent is not to educate readers on Singlish in any prescriptive manner. Nor is it meant to be merely descriptive of how Singlish actually sounds like; the first sentence in the blurb above already makes this clear. The real intent of the book is rather to ludify English, that is, to fashion a ludic register out of Singlish. Ludification denotes playfulness in respect of all aspects of culture. Raessens (Reference Raessens, Fuchs, Fizek, Ruffino and Schrape2014:94) maintains that play

is not only characteristic of leisure, but also turns up in those domains that once were considered the opposite of play, such as education (educational games), politics (playful forms of campaigning, using gaming principles to involve party members in decision-making processes, comedians-turned-politicians) and even warfare (interfaces resembling computer games, the use of drones—unmanned remote-controlled planes—introducing war à la PlayStation).

Just as education, politics, and warfare can be rendered playful, so can language. Spiaking Singlish underscores the ludification of language, where English is punctured all around by Gwee's Singlish interventions. The best place to start is the book's introduction, which self-professes as a ‘Cheem introduction’—cheem (‘deep’ in Hokkien) meaning sophisticated, as in ‘depth’ of knowledge; here the (mis)alignment of a vernacular with sophistication points to a self-mocking, tongue-in-cheek undertone that informs the entire work. Tellingly, Gwee (Reference Gwee2018:13) does not shy away from self-praise with full irony intended: he lauds his book as sibeh kilat ‘above excellent’, ‘hands-down the cheemest Singlish book in print ever or at least to date’, where cheemest instances Singlishism (Wee Reference Wee, Mathews and Fong2016:53) by inflecting cheem with a superlative suffix.

Singlishisms demonstrate the creative dynamism of stylised English-based practices in the Kachruvian outer and expanding circles, in which words of non-English origin are often meshed into English morphologies to create contingent, locale-specific formations (Lee & Li Reference Lee, Wei and Kirkpatrick2021). Take, for example, the book's first entry on the word anyhowly, the Singlish variant on ‘anyhow’. In explaining why Singlish would appropriate an existing English word without changing its meaning substantively, Gwee takes the opportunity to propose his own linguistics ‘law’.

Here's a good time for me to share one typical way I fewl [eye-dialect spelling of ‘feel’] Singlish as a language develops. To be sure, ‘anyhow’ is a sibeh tok kong [‘extremely powerful’] word for the Singaporean mind, which is always stuck between a love of freedom and a fear of luanness [‘disorder’]. It's macam [‘as though’] God made this word for us one! [Singlish structure] But, when a Singlish term kena [passive marker] used a lot, something I call Gwee's First Law of Singlish Dynamics kicks in. This law states that a frequently employed expression tends towards a rhyme. (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:28; original emphasis, parenthetical glosses mine)

The so-called Gwee's First Law of Singlish Dynamics is a nonce creation given to the author's personal, untested observation of a Singlish pattern; it is deliberately cloaked in pseudo-academic nomenclature, with the ‘Family Name + First Law of… Dynamics’ structure parodying the labels of famous scientific theories (think Newton's Second Law of Motion, and so on). No reader is expected to ascribe any intellectual intent to this ‘law’, meant to create a disjunct between the apparent triviality of Gwee's observation and its heady title, and a jarring gap between the unofficial status of Singlish and its grandiose appellation. The result is a wry humour that speaks to an overall ludic character underpinning the book. Gwee in fact reflexively captures the theme of ludification himself in the same entry, in what he calls his Second Law of Singlish Dynamics: ‘a frequently used expression tends towards humour’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:30; original emphasis).

The ludic quality of Spiaking Singlish derives in part from the way it defamiliarises Singlish. Although the individual terms introduced in the book are themselves unmarked in conversational settings, they are collocated with such intensity as to give rise to a hyperbolic display of street multilingualism in Singapore. The following metacommentary on the history of Singlish illustrates my point.

Singlish has long-long history one! [one: emphatic sentence-final particle] Dun [‘Don't’] listen to some people talk cock sing song [‘utter nonsense’] and anyhow say this, say that. These who suka [‘like’] talk cock—that is, engage in nonsensical or idle talk—we call talk cock kings. They say got no Singlish before Singapore was independent [got: existential marker, equivalent to ‘there+BE’]. They say last time only got [Singlish existential verb] Melayu [‘Malay’] and cheena [‘Chinese’] dialects campur-campur [‘to mix’] but no England [‘English’] because people bo tak chek [‘did not study’, meaning had little education]. Lagi [‘even’] worse, they say Singlish only became tok kong [‘potent’] when Singaporeans felt rootless and buay tahan [‘unable to tolerate’] Spiak Good England Movement [‘Speak Good English Movement’]. Wah piang eh [interjection, equivalent to ‘Oh my god’]! No lah! [emphatic sentence-final particle] (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:80; original emphasis, parenthetical glosses mine)

This passage features a rhythmic Singlish marked by such a high degree of heteroglossia as to render it theatricalised; it is a high performance (Coupland Reference Coupland2007) of Singlish based on an ironic parody of everyday Singlish. In this performance, words and phrases are decontextualised from their ordinary conversational settings and recontextualised within a self-styled ‘companion to how Singaporeans communicate’ (the book's subtitle). Such entextualisation (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:73) involves resemiotising (Iedema Reference Iedema2003) formal features of the spoken vernacular into textual resources for a ludic metadiscourse, which produces an articulate breed of Singlish that is, ironically, also not Singlish.

It is crucial to appreciate this rhetorical transformation of Singlish from street vernacular to performative register in Spiaking Singlish. In the terms of Bauman & Briggs (Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:75), based in turn on the Goffmanian notion of framing, the book's companion genre and format constitute a ‘metacommunicative management’ of the text. The entextualisation of colloquial Singlish terms within the frame of a quasi-academic genre creates tension between the oral and the written, the prosaic and the (pseudo-)scholarly. This tension generates humour while hinting at the subversive potential of Singlish to function as a written language in its own right. In this regard, the book's paratextual features—its self-naming as a ‘companion’, the alphabetical ordering of entries as per dictionaries or glossaries,Footnote 5 the quirky Singlish ‘quiz’ at the end modelled on the familiar multiple-choice question format—all need to be interpreted as part of an ironic frame that is evocative of a language orthodoxy, subverted from within by means of a Singlish metalanguage.

In terms of form (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:75), the recursiveness involved in explaining Singlish in Singlish creates a self-sufficient, endonormative loop that results in locale- and register-specific entertainment, spurring laughter for ‘in-group’ speakers ‘in the know’. Such metadiscursivity calls attention to the form of the discourse itself, that is, the entextualised Singlish formulations, including their morphological flexibility (e.g. non-English words inflected as though they were English words), orthographical contingency (eye-dialect spellings), and, as noted above, hyperbolic multilingualism created by radical codeswitching. Finally, the function (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:75–76) of the seemingly light-hearted metadiscourse is an ideologically charged one. It is to establish the autonomy of Singlish by taking it from a spoken vernacular to a written medium, and to convey the message that Singlish is not to be evaluated with reference to the exonormative (from the vantage of Singlish) criteria of Standard English. In this regard, Gwee's suggestion that Singlish possesses a ‘dynamics’ governed by its own ‘laws’ (cited above) speaks directly to the politics of styling Singlish within and against a language ideological regime that systematically militates against it.

From style to stance

Style is a surface manifestation of and a ‘shorthand’ for stance (Kiesling Reference Kiesling2009). The whimsical style of Spiaking Singlish coheres with the perceived informality of the vernacular and foregrounds the book's ludic character. This stance is evident in several passages in the book's introduction, in which Gwee explicitly argues against the government's (always [mis]spelled as Gahmen; see below) view on Singlish. In one exemplary instance, he declares that government efforts to ‘blame social immobility on Singlish and then try to kill Singlish’ are ‘smart’ (ironically meant) but futile. He then dishes out his insolent admonishment: ‘Whack Singlish for fiak since you cannot stop people from anyhowly?’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:22)—roughly translating into: ‘Why the f*ck are you censuring Singlish since you can't stop people from messing up their language?’, where the implied referent is the Singapore government.

Gwee's Singlish is therefore more than a tongue; it is loaded with ideological freight in relation to language politics. As Gwee wryly notes, ‘Singlish is different [from the four official languages]: it gets no love from the Gahmen’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:14). The iconoclasm here cannot be more obvious: Singlish is an unwanted child disdained by the government. Here the eye-dialect orthography emblematises a resistant discourse; Gahmen is an eye-dialect variant of ‘Government’ inflected with a distinctively Singlish accent. By imparting a contingent written form to a word rooted in orality, Gwee is not reverting to the discursive authority he seeks to transgress, but is rather deconstructing such authority by attaching a spurious Latin transcription to a vernacular that does not by default possess its own script. Given that Singlish is rooted in the patois, the use of eye-dialect in words such as spiaking in the title and Gahmen here points to a transgressive ethic.Footnote 6 It contingently transforms the oral-aural transience of a spoken variety into the visual-verbal fixity of a language equipped with an apparent orthography.Footnote 7 And the resistant nature of this Singlish orthography is especially loaded in the present example where the word in question happens to be ‘government’.

Such invented spellings, which probably gained traction as a practice during the early days of text messaging, are a highly performative gesture (cf. Tagg Reference Tagg2012). On this view, what is important about Spiaking Singlish is the identity stance it enacts through Singlish. As suggested earlier, Singlish as rhetorically articulated in the book, with its disproportionately high concentration of Singlish-inflected syntax as well as lexis from Malay and the Chinese dialects, is something of a caricature of Singlish as it is empirically attested. Gwee's metadiscourse, therefore, does not so much represent as it enregisters Singlish, weighting it with the egalitarian values it is perceived to index and setting it up against Standard English—the latter weighted with the supposedly elitist values of the establishment.

Enregistering Singlish

On the question of enregisterment, Johnstone, Andrus, & Danielson's (Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006) study of Pittsburghese, an ‘imagined dialect’ frequently used in southwestern Pennsylvania, provides a comparative case for us. Drawing on Silverstein's (Reference Silverstein2003) indexical orders, Johnstone and her associates investigate several layers of social meaning generated by Pittsburghese, postulating three indexical orders. First-order indexicality comes into being when formal features of speech become associated—by linguists, not by the speakers themselves—with sociodemographic identity; for example, the monophthongal /aw/ as an ‘indicator’ (Labov Reference Labov and Fishman1971) of speech variation among working-class men from Pittsburgh. The correlation between linguistic form and social meaning on this first order can then be abstracted upward to form a second-order indexical. This is where speakers themselves begin to interpret formal features in their speech as ‘markers’ (Labov Reference Labov and Fishman1971) of ascribed social meanings and/or to perform (or refrain from performing) those features to enact the attendant social meanings. For example, given that the monophthongal /aw/ is associated with working-class males on first indexical order, speakers from Pittsburgh may employ this phonetic feature more audibly to play up a working-class ethos, or less audibly to portray a more cosmopolitan outlook.

Most important for our purpose is the notion of third-order indexicality, which comes about when people make conscious connections between formal features typically associated with a language variety and a locale-specific, place-based identity. In the case of Pittsburghese, the monophthongal /aw/ turns into a third-order indexical when ‘it gets “swept up” into explicit lists of local words and their meanings and reflexive performances of local identities, in the context of widely circulating discourse about the connection between local identity and local speech’ (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006:84).

On this third indexical order, features from Pittsburghese are proactively appropriated, often ‘in ironic, semiserious ways’ (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006:83), for their entrenched connections with a place, in this case Pittsburgh. This has resulted in metadiscursive practices and artefacts ‘that have enregistered local speech in the local imagination as unique and unchanging’, reinforcing, indeed stereotyping (cf. Labov Reference Labov and Fishman1971) ‘the ideological links between local speech and place’ (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006:94). These include, for example, articles on local newspapers describing phonological, lexical, and grammatical features seen as distinctive to Pittsburghese, with a view to piquing ‘local curiosity about local speech’ (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006:95). Further developments saw attempts to construct an aura of legitimacy around Pittsburghese by co-opting expert testimonies from dialectologists. Also witnessed were the rise of vernacular publications, including folk dictionaries such as Sam McCool's new Pittsburghese: How to speak like a Pittsburgher and websites such as www.pittsburghese.com devoted to engaging young adults in ‘folk-lexicographic activity’ pertaining to Pittsburghese (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006:97).

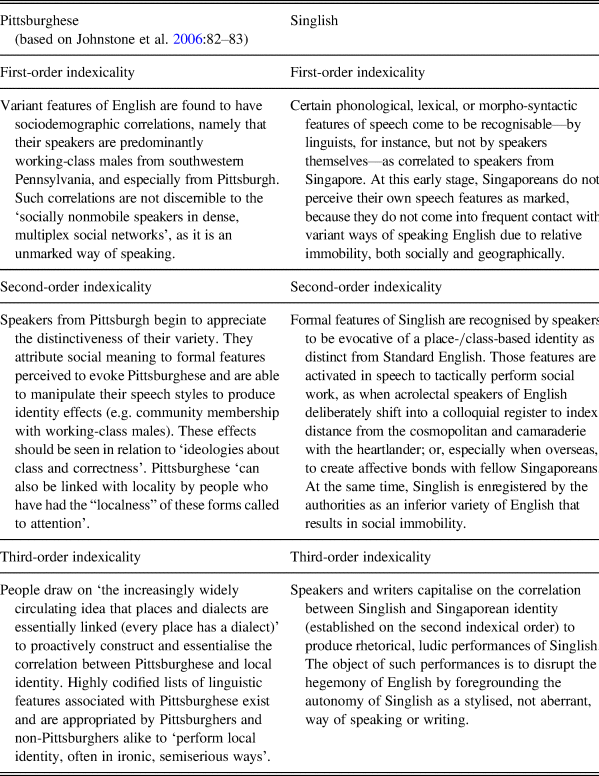

The sociohistorical background against which Singlish has evolved is very different from that surrounding Pittsburghese. Yet the two share the common destiny of being enregistered to index locality (and to some extent, a working-class identity), leading to their commodification in marketing contexts, as exemplified in Pittsburghese/Singlish T-shirts. Spiaking Singlish can be seen as a ‘folk-lexicographic activity’ participating in such commodification, similar in nature to Sam McCool's folk dictionary. Johnstone and colleagues’ analysis thus offers a useful framework to postulate the indexical trajectories negotiated by Singlish. Table 1 summarises the three indexical orders of Singlish modelled on the case of Pittsburghese, although such comparison in no way suggests that their historical paths are exactly parallel.

Table 1. Indexical orders: Pittsburghese and Singlish compared.

As a first-order indexical, Singlish has long been studied as a linguistic curiosity, with scholars (some of whom are non-speakers of the variety) undertaking fine-grained analysis of its formal features.Footnote 8 Early studies (Platt Reference Platt1975) tend to see these features as intrinsic to the hybrid language situation in Singapore and as emblematic of relatively low levels of education and disadvantaged socioeconomic status of its speakers. On this order, the potential of Singlish to index sociodemographic attributes (i.e. relatively less educated residents of Singapore) is established as a matter of intellectual interest. That potential has not been taken up by the speakers themselves, that is, the persons-in-the-culture, to actively instantiate a place-/class-based identity. On the second order, phonological and lexicogrammatical features associated with Singlish on the first order are taken up by speakers themselves to signal their identity as ‘locals’, thereby delineating an ingroup/outgroup membership. As Alsagoff's (Reference Alsagoff2010) cultural orientation model and Leimgruber's (Reference Leimgruber2013) indexical model demonstrate, speakers are able to consciously slide between Singlish and English to express an orientation along the local-global spectrum and, more specifically, mobilise formal features associated with Singlish or English to index affective stances—formality vs. informality, solidarity vs. distance, and so on. Yet on this indexical order, Singlish departs from Pittsburghese in that it is concurrently stigmatised by the state as a ‘broken’ variety of English (Wee Reference Wee, Mathews and Fong2016:49), one that impairs children's acquisition of Standard English and interferes with the nation's participation in the global economic order. Language labels such as ‘broken English’ are markers of enregisterment (Møller & Jørgensen Reference Møller, Normann Jørgensen, Møller and Normann Jørgensen2011). Thus, by systematically labelling Singlish as ‘broken English’, official discourses enregister Singlish as a low-proficiency version of English and a hindrance to the nation's path toward globalisation.

On the basis of the second indexical order, the third indexical order emerges in metadiscursive practices and artefacts that appropriate Singlish, often in jest, to reflexively flaunt an edgy place-/class-based identity. These practices and artefacts stereotype formal features of Singlish, stabilising and essentialising their indexical potential in connection with the imagined construct of ‘Singaporeanness’, as opposed to a cosmopolitan Singaporean identity espoused by state. On this order, Singlish can be invoked to activate ‘a nostalgic sense of belonging and a youthful sense of urban hipness’, as Johnstone (Reference Johnstone2010:399) says of Pittsburghese. Such valorisation of Singlish as metonymic of an authentic Singaporean identity is often performed with ironic intent, as with Spiaking Singlish, serving as a ludic corrective to state discourses that censure Singlish as an aberrant version of English.

Singlish as fetish

We are now in a position to understand Spiaking Singlish from the perspective of indexical orders. The work represents a rhetorical deployment of Singlish, based on the cultural associations the language has attracted on the lower (second) indexical order, to proactively index mundane as opposed to cosmopolitan sensibilities. In other words, prior usage of Singlish as the default medium to encode a heartlander ethos is reinscribed by Gwee to articulate a critical metacultural discourse on a higher (third) indexical order.

Importantly, the critical edge of Gwee's prose on the third indexical order is premised on a two-way enregisterment on the second indexical order. As mentioned above, Singlish on the one hand is invested with a perceived rustic vitality thanks to the many (including vulgar) colloquialisms in its repertoire—mostly sourced from Hokkien; and on this account, it bears a strong association with an imagined authenticity based on what is perceived as ‘low-brow’ culture. On the other hand, official narratives have maintained the consistent narrative that Singlish is the inferior cousin of Standard English. Due to its enregisterment by the authorities as ‘broken’ English, Singlish is driven underground, as it were, effaced from official representations of multilingualism and branded a subterranean variety indexing unsophisticated personalities and non-cosmopolitan outlooks. In this regard, Singlish parallels Pittsburghese, where ‘the same features that are in some situations, by some people, associated with uneducated, sloppy, or working-class speech can, in other situations and sometimes by other people, be associated with the city's identity, with local pride and authenticity’ (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009:160).

It is at this juncture that we can begin to appreciate Spiaking Singlish as a language ideological intervention: as Singlitterati individuals like Gwee move up the hierarchy of indexical orders, they both expose and capitalise on the gap between the third order where metadiscursive practices thrive, and the second order where official language policy discourses remain. More specifically, it is against the state's delegitimisation of Singlish on the second indexical order that the book seeks to acquire legitimacy for the vernacular on the third order by way of fetishising its form; that is, by creating an impression of consistency and standardisation as regards its words, sounds, structures, and orthography, with a view ‘to see[ing] whether Singlish can be written long-long [‘in long form’] and with intelligence anot [‘or not’]’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:15; parenthetical glosses mine).

This will toward consistency and standardisation evidences a lexicographical aspiration along the line of the ‘highly codified lists’ of Pittsburghese words (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006:83). But it must not be interpreted as a metadiscursive regimentation (Makoni & Pennycook Reference Makoni, Pennycook, Makoni and Pennycook2007:2) of the vernacular, that is, the simple consolidation of a ‘grassroots’ tongue to a binding framework without a higher-level performative intent. That kind of consolidation, as exemplified for instance by The dictionary of Singlish and Singapore English,Footnote 9 subsists on the second indexical order. Instead, we must see Gwee as fully operating on the third order, which allows him to exploit the already fossilised indexical potential of Singlish on the second order and to commodify the vernacular into a metadiscursive instrument in critique of extant language policies. This explains why Singlitterati like Gwee can easily construct the language establishment as static and conservative. The latter qualities are a discursive effect of the disparity between the nth and n + 1st indexical orders; and because the n + 1st order rides on the nth order, any discourse undertaken on the higher order will become apparently dynamic and experimental compared to that undertaken on the lower order.

It is on this third indexical order that Gwee, by means of a stylised, scripted, and metalinguistic performance of Singlish, can be said to position himself as a ‘legitimate contributor’ as opposed to a ‘passive consumer’ of English in the Singapore context (Wee Reference Wee, Mathews and Fong2016:58). To borrow Bauman & Brigg's formulation (Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:76–77), Gwee is affording himself the authority to appropriate Singlish ‘such that [his] recentering of it counts as legitimate’. Drawing on the Singlish lexicon as a resource to project a locale-based identity and to engage official language discourses in a provocative way, he effectively turns Singlish from a language variety through a social language (Gee Reference Gee, Aronoff and Rees-Miller2001) into a discursive style (Wee Reference Wee, Mathews and Fong2016:51). In this regard, he demonstrates what Wee (Reference Wee2018:79) calls linguistic chutzpah—a linguistic ‘confidence that is backed up by meta-linguistic awareness and linguistic sophistication, giving the speaker the ability to articulate, where necessary, rationales for his or her language decisions’ (cf. Schneider Reference Schneider2007:289).

More precisely, Gwee embodies Wee's (2016:58) ideal user of English in Singapore, who can ‘confidently engage in informed metadiscourses about evolving linguistic standards and appropriateness which may serve as a fundamental resource for contesting the hegemonic construct of the traditional native speaker’. But he does not stop there. He rejects outright the proposition that Singlish is even a variety of English, claiming that Singlish and English are only occasionally similar: ‘The two are, in fact, macam [‘as though’] apples and oranges—and becoming more and more so’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:16). This apples-and-oranges theory overstates the autonomy of Singlish, but that overstatement is itself telling of the book's belligerence toward language doxa. It corroborates Gwee's performance of an extreme Singlish, an unnaturalistic concoction of that which is used on the streets.

It is here that Singlish, in my view, gains a more political edge than Pittsburghese; it is not merely commodified but politicised. The rhetorical articulation of Singlish on the third indexical order essentialises the correlation between (vernacular) language and (grassroots) identity, already established on the second indexical order. It makes a fetish out of Singlish, leveraging it into a sardonic voice against the state's longstanding enregisterment of Singlish as an aberrant offshoot of multilingualism and its fetishisation of Standard English as the orthodox benchmark. Hence, the agenda of Spiaking Singlish is not merely to provide infotainment; it is to trigger the language bureaucracy, represented by Standard English, by way of a marked Singlish that exoticises a naturally occurring tongue into a transgressive counterlanguage. And all of this is superbly delivered in a nonserious tone throughout, speaking to a ludic (third-order) choreography that mocks the (second-order) technocratic standoffishness of official discourse.

Now we need to push further and ask: What happens to a vernacular like Singlish when it is articulated to the third indexical order? Are we still looking at the same thing with which we started on the first order? It is here that Spiaking Singlish presents a potential risk in terms of reception: the uninitiated reader (e.g. a curious foreigner, a linguist unaccustomed with Singlish) may well perceive Gwee's meta-language as a demonstration of empirical Singlish. As noted above, the brand of Singlish presented in the book is but a rhetorical incarnation, a far cry from Singlish as it is spoken. It features novel coinage that rips off the morphology of English, boasts a certain sophistication in phrasing that speaks to Gwee's craft as a professional writer, and showcases a dramatic mixing of languages that renders it marked—hence entertaining—even for so-called native speakers.

All of this, of course, makes perfect sense within the generic and ideological context of the book; and to Gwee's credit, he concedes in the introduction that his Singlish prose is a ‘thinking Singlish’ that is unlike everyday Singlish: ‘more England-based [‘English-based’] and sikit cheemer [‘a bit more difficult’], not macam [‘as though’] what you may find normally elsewhere’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:15). It is therefore pertinent to understand Gwee's prose not as a pedagogical exercise, but as a tactical experiment in enregistering Singlish to romanticise a vernacular identity and codify nonconformity. It is conceived at the outset not so much to teach Singlish as to subvert the more powerful frame of Standard English and, as a corollary, to reverse the state's stigmatisation of Singlish as ‘broken English’. On this reading, to turn Singlish into a folk-lexicographic project is to undertake a radical, experimental response to the normativising force of Standard English in the state-designed education system, so as to ‘potong a way to a lagi tok kong Singlish’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:15; emphasis added)—that is, to carve out a path toward a very powerful Singlish. The question is whether this lagi tok kong Singlish is still the same creature as the endeared vernacular spoken by the populace; and if not, whether the metadiscourse pivoting around Singlish leads to an ethical dilemma in which the object being celebrated is in fact absent.

Gwee's controversy

To unpack this ethical dilemma, we need to look beyond Gwee's book and delve into the layers of backstories it draws out. These backstories unravel the tensions between Singlish advocates and the language establishment that underpin the political economy of metadiscourses promulgating the value of Singlish. As I have suggested above, these tensions arise within the gap between the different indexical orders on which the opposing parties subsist; and because they operate on irreconcilable indexical orders, the parties are, in a manner of speaking, talking across each other, resulting in an ideological impasse. For reasons of space, we examine just one of these episodes in detail, involving a paper war between Gwee and the press secretary to Singapore's Prime Minister.

On 13 May 2016, two years before the publication of Spiaking Singlish, Gwee published an op-ed in the New York Times (NYT), titled ‘Politics and the Singlish language’, later retitled (for unknown reasons) in its online version as ‘Do you speak Singlish?’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2016). The original title clearly signals the political intent of the piece, alluding as it does to George Orwell's 1946 essay ‘Politics and the English language’. By pronouncing Singlish as a language (without scare quotes), which in the Singapore context is to strike a sensitive nerve of the official language policy, it establishes at the outset the author's recalcitrant stance. Paradoxically, although Gwee is against Singlish being turned into ‘Singapore's most political language’ and seeming ‘to thrive on codifying political resistance’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2016), he in fact actively partakes of the alleged politicisation on the third indexical order. The NYT op-ed manifests how Gwee himself intentionally positions Singlish against the government's language policy, making a case for Singlish to be vindicated of the negative press it has been receiving from the establishment.

The piece opens provocatively with a war metaphor: ‘Is the government's war on Singlish finally over? Our wacky, singsong creole may seem like the poor cousin to the island's four official languages, but years of state efforts to quash it have only made it flourish. Now even politicians and officials are using it’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2016). Here, in his characteristically ironic tone, Gwee sets the stage by positioning Singlish as an underprivileged, victimised language (‘wacky, singsong creole’, ‘poor cousin’) that continues to proliferate in the face of state oppression. Such positioning belies and reifies the dichotomy between Singlish vs. the State, which Gwee is purportedly against. Yet is Gwee himself totally absolved from the enterprise of politicising Singlish? Although he appeals for people to ‘dun stir and simi sai oso politisai’ (‘not create controversy and politicise everything’) (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:17), he simultaneously ascribes a strong political stance to Singlish by invoking the government's anti-Singlish policy as a target to be critiqued. (Such ascription is carried through in the section ‘Singlish got history’ in Gwee's introduction to Spiaking Singlish; Gwee Reference Gwee2018:17–20.) One might question whether, by explicitly calling out the government, Gwee's NYT piece is not also responsible for further embroiling Singlish in politics.

Further witness how Gwee systematically entrenches a war metaphor in his arguments (Gwee Reference Gwee2016; emphasis added):

Singlish, now an enemy of the state, went underground. But unlike the beleaguered Chinese dialects, it had a trump card: It could connect speakers across ethnic and socioeconomic divides like no other tongue could…

…Singlish's status grew so powerful that the Chinese dialects took refuge in it to re-seed themselves.

The government's war on Singlish was doomed from the start. Even state institutions and officials have nourished it, if inadvertently. The compulsory national service, which brings together male Singaporeans from all walks of life, has only underlined that Singlish is the natural lingua franca of the grunts.

Conceptual metaphor theory (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson2003) tells us that metaphors provide us with a schematic frame within which we cognise our reality through ontological mappings and epistemological extensions. Thus, Gwee's war metaphor ontologically figures the Singapore government as an aggressor and Singlish as a guerrilla force (‘an enemy of the state’ that ‘went underground’). The epistemological implication is that Singlish is a democratic language of the masses (‘the natural lingua franca’) that needs to keep fighting to prevent itself from being ‘beleaguered’ by the bureaucracy. I stress the metaphoricity of Gwee's argument to underline the rhetorical nature of his activist discourse. This kind of metaphorisation is the business of a higher-order indexicality, for it is on this order that one can go beyond recognising the indexical meaning of a language (achieved on the second indexical order) and turn it into a radical performance such as a pointed metadiscursive critique. It does not follow that the general point Gwee makes is an untruth. The government has indeed installed structural policies and campaigns to discourage the widespread use of Singlish. Yet to say that this is tantamount to a war on Singlish is to evoke a pointed metaphor evincing a very specific language ideology. That same metaphor is not attested in official discourses on Singlish; it is part of a rhetorical praxis on Gwee's part. It discursively produces an asymmetric and irreconcilable relationship between Singlish and the language establishment, with a view to eliciting empathy from readers for the former, construed as an object of stigmatisation on a lower indexical tier.

Thus, the status of being stigmatised on the second order can in turn be leveraged and transformed into a resource for popular appeal on the third order. This is the juncture where Gwee expressly politicises Singlish by imputing to it a subversive, countercultural value, thereby resignifying it from a vernacular into a stance, an ethos: ‘the more the state pushed its purist bilingual policy, the more the territory's languages met and mingled in Singlish. Through playful, day-to-day conversations, the unofficial composite quickly became a formidable cultural phenomenon’, says Gwee (Reference Gwee2016). More than that, a generational element is introduced to reconfigure the act of speaking Singlish into an act of youthful defiance to authority: ‘And in the eyes of the young, continued criticism by the state made it the language of cool’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2016). Emblematising Singlish into a signifier of the heteroglossic, young, vibrant, chic—hence constructing by implication the state's policy as monoglossic, traditional, stifling, out of sync—Gwee imbues Singlish with a new set of indexical meanings to counteract those inherited from official discourses. He effectively resignifies the perceived incorrectness of Singlish (with reference to Standard English, as always) into a political incorrectness as he takes the vernacular from the second to the third indexical order.

In his effort to qualify Singlish as ‘a formidable cultural phenomenon’ against official language policy, Gwee thus renders the question of Singlish into a political one through and through. For him, the fact that politicians and officials are occasionally tapping into Singlish is evidence that even the establishment cannot but succumb to the vibrancy of the vernacular, with the implication that the people's tongue must ultimately prevail: ‘Now even politicians and officials are using it’; ‘The tourism board can't help but showcase it as one of Singapore's few unique cultural creations’; ‘Finally grasping that this language is irrepressible, our leaders have begun to use it publicly in recent years’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2016). Gwee appears to be suggesting that the state has contradicted itself in using Singlish in public relations work. But in the terms developed in this article, this only shows that the state has developed a measure of reflexivity in respect of the vernacular: it is now able to tactically appropriate Singlish on the third indexical order to achieve pragmatic ends (e.g. to attract a larger electorate base), while still maintaining their official stance on the second order that Singlish is a lingua non grata (Wee Reference Wee2018:41).

The most political moment in the op-ed comes at its denouement, where Gwee cites what he calls a ‘blunder’ made by none other than the Prime Minister himself. The blooper in question, ironically described as ‘a precious contribution to the [Singlish] lexicon’, was the Prime Minister's alleged invocation in a national address of the putative local dish mee siam mai hum (Malay vermicelli noodles without cockles). As Gwee points out, the noodle dish mee siam is never served with cockles to start with. It could be that the Prime Minister meant to reference laksa, another local delicacy usually served with cockles; alternatively, he could have intended to say mee siam mai hiam (Malay vermicelli noodles without chilli), mispronouncing hiam ‘spicy’ as hum ‘cockles’. At any rate, the Prime Minister's inadvertent mistake is arrested by Gwee and construed as a Freudian slip indexing elitism, a failure on the part of state leaders to engage with language realities on the streets. The episode—for Gwee, that is—‘happily became Singlish for being out of touch’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2016).

The establishment hits back

The Office of the Prime Minister was not amused. On 23 May 2016, ten days after Gwee's op-ed was published, Chang Li Lin, then press secretary to the Prime Minister, retaliated with her own op-ed in the NYT, titled ‘The reality behind Singlish’ (Chang Reference Chang2016). Chang's profile meant her opinion represented the position of Singapore's highest office, with the local media reporting the controversy the following day.Footnote 10

In her short piece, Chang first maintains that Gwee's article ‘makes light’ of government efforts in promoting Standard English among Singaporeans, insisting that there is ‘a serious reason’ behind such efforts, hence implying the frivolity of Gwee's argument. Chang then proceeds to explain the importance of Standard English to the livelihood of Singaporeans and to effective communication among Singaporeans as well as between Singaporeans and the global community of English speakers. Taking a pedagogical line, she maintains that learning English requires ‘extra effort’ on the part of the majority of Singaporeans for whom English is not a mother tongue, and that Singlish may further impede such efforts—this is the template ‘interference’ argument often used by the authorities (Wee Reference Wee2018:84–85). Chang concludes with a sarcastic statement targeting Gwee: ‘Not everyone has a Ph.D. in English Literature like Mr. Gwee, who can code-switch effortlessly between Singlish and standard English and extol the virtues of Singlish in an op-ed written in polished standard English’ (Chang Reference Chang2016).

What Chang points out in her closing remark is the paradox facing Singlitterati in the likes of Gwee, or more generally, the ethical dilemma of promoting a street vernacular like Singlish. I mentioned earlier that Gwee re-signifies Singlish into a wayward medium by weighting it with countercultural values (‘the language of cool’). The underlying assumption is that Singlish speakers in general have the ability to manoeuvre the language in ‘day-to-day conversations’ with such dexterity as to render it ‘playful’ and ‘cool’ (Gwee's words, cited earlier). Yet there is nothing inherently ‘playful’ or ‘cool’ about Singlish per se; those qualities are ideological constructs, manifested as rhetorical style (think the metalanguage of Spiaking Singlish). They do not inhere within the lexis or structures of the register as such but are performed into being. It is only highly educated individuals like Gwee who possess the metapragmatic knowledge and metalinguistic skills to perform Singlish as a third-order indexical; the vast majority of the Singlish speakers are stranded on the lower orders, including on the first order, where speakers may only be vaguely aware of the peculiarity of their speech due to relative social and geographical immobility.

In this regard, it is interesting to read Chang's sarcasm on Gwee's paradox against what Wee (Reference Wee, Mathews and Fong2016) maintains about the government's undifferentiating approach as to who uses Singlish:

By using the label ‘Singlish’ in this manner [as ‘bad’ or ‘broken’ English], the government is either unable or unwilling to distinguish speakers who have little or no competence in Standard English (and thus speak a largely ungrammatical variety as their only variety of English) from speakers who are competent in Standard English (and who code-switch into a colloquial variety for strategic interactional purposes). (Wee Reference Wee, Mathews and Fong2016:49; emphasis added)

By stating that ‘[n]ot everyone has a PhD in English Literature like Mr. Gwee, who can code-switch effortlessly between Singlish and standard English and extol the virtues of Singlish in an op-ed written in polished standard English’, Chang disproves Wee's point: the government does indeed distinguish between these two groups of Singlish users. Chang's statement indicates that the government is keenly aware of the importance ‘not to lose sight of the fact that speakers who confidently manipulate linguistic resources to perform… Singlish are socio-linguistically distinct from those who speak what might be categorized as ungrammatical English because they lack the ability to do otherwise’ (Wee Reference Wee2018:85). Rehashed in our terms, she is effectively critiquing privileged Singlitterati individuals for indulging in metadiscourses on higher indexical orders while neglecting the vast majority of Singlish speakers who are still stranded on the lower orders.

Gwee did not miss the opportunity to ride on this controversy. In Spiaking Singlish he references the incident and cites Chang's rebuttal, self-derisively speaking of himself as kena buak gooyoo (‘being reprimanded’, usually by someone in authority) for sayanging (‘caring for’) Singlish (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:20). And it is in this light that Spiaking Singlish should be interpreted as an extension of the NYT op-ed episode. By using Singlish as a metalanguage in his book, Gwee seeks to nullify his paradox of ‘extol[ling] the virtues of Singlish’ in a ‘polished standard English’ in his op-ed, as alleged by Chang in her counter op-ed. The use of Singlish to sustain a book-length commentary about Singlish highlights its capacity to operate as a language ‘proper’: just as Standard English can be used to represent the linguistic features of the English language in reference texts, so Singlish can be used in talk about talk as a full-fledged language, contrary to its officially imputed status as a subterranean tongue. On this reading, the mischievous tone of the prose is crafted to match its metacultural intent; it affords the problem of Singlish a deliberately ludic touch, as though ironically alluding to Chang's charge that Gwee ‘makes light’ of government efforts in promoting English.

All of this leads us to ponder the ethics of celebrating a vernacular like Singlish by stylising it on the third indexical order. We have seen that Gwee champions the use of Singlish by appealing to a heartlander ethos; but as Wee (Reference Wee2018:11) observes, ‘[t]he rhetorical emphasis on Singlish as a builder of solidarity across all Singaporeans seems to ignore or at least downplay those cases of Singaporeans who are either unable or unwilling to speak Singlish’. This seems to be the case with Gwee. In his bid to challenge government policies on Singlish, Gwee takes for granted that Singlish users are generally able to deploy Singlish to ludic effect (‘playful’) or for countercultural purposes (‘cool’ by virtue of its being officially censured). This disregards the fact that most Singlish users are not operating on the third indexical order; monolectal speakers, in particular, use Singlish as a practical medium of communication on the first and at most the second order, and it would be presumptuous to think this group of Singlish users would be consciously using Singlish rhetorically as ‘the language of cool’ to project a rebellious identity.

Given that Gwee sets out to celebrate the vernacular creativities of Singlish, his vision of Singlish is paradoxically romantic and elitist, premised as it is on users having a sufficiently high proficiency in English to proactively appropriate resources from Singlish to enact identity or political stances. His resignification of Singlish is therefore mythical in a Barthian sense (Barthes Reference Barthes1957/2012); it renders values such as playfulness and coolness apparently natural to the language itself when they are in fact ideological. Textually, this romantic vision manifests in Gwee's scaled-up, elaborate, and sophisticated register of Singlish as seen in Spiaking Singlish, one that features all elements of the mundane vernacular but is ultimately anything but mundane.

Conclusion

Highlighted in this case study is the ethical question of whether a highly educated intellectual who shuttles fluently between the vernacular and the standard can in fact speak on behalf of the general, monolectal user of the vernacular. As discussed above, a fundamentally elitist assumption underlies Gwee's position on promoting Singlish, namely that general users of English in Singapore can codeswitch between the colloquial and the formal. Gwee's agenda thus implicitly excludes Singlish users who do not have the linguistic resources to readily switch into the formal register. On this note, it is important to recognise that the capacity to codeswitch is a privilege—I agree with Chang Li Lin on this specific point. For monolectal Singlish users, Singlish is a survival tool that does not even rise up to the second indexical order; it is not some curious resource for self-styling, nor a site for fetishising a heartlander identity against cosmopolitan imperatives, which belong to an exclusive third indexical order which not everyone has equal access to. Gwee pivots his writing unequivocally toward the heartland while choreographing a highly performative, non-spontaneous brand of Singlish replete with humorous rhetorical feats, which paradoxically bespeaks the cosmopolitan. Such iconoclastic practices are valuable in bringing more visibility to a marginalised language; but they also risk romanticising the language-identity nexus, turning the language from a rich, naturally occurring vernacular into the empty signifier (à la Barthes) of a nebulous ‘local consciousness’. As with the prose of Spiaking Singlish, the vernacular may also in this process be transformed into a different creature, one which, ironically, may not be fully recognisable to its ordinary users.