Impact statement

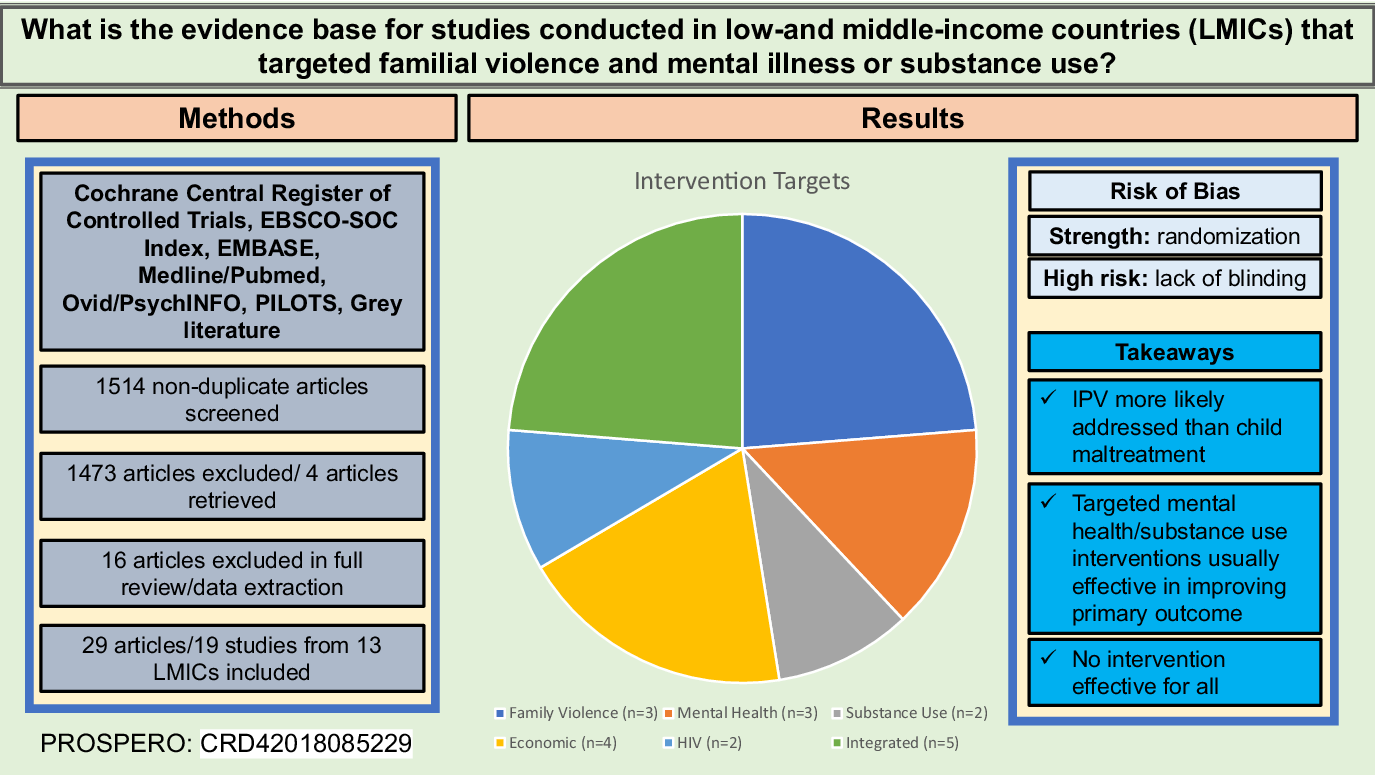

Family violence affects between 15% and 71% of women and 75% of children worldwide and is a pervasive global health problem with a cascade of physical, psychological, and social consequences. While family violence has strong associations with substance use and mental illness, interventions that comprehensively address these related problems are lacking. Further, most family violence research has been conducted in high-income countries, although family violence rates are higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and outcomes are more severe. Despite the elevated need for LMICs, these settings have fewer resources to respond to family violence, and there is a paucity of trained mental health professionals in LMICs that contribute to large gaps in treatment. This systematic review of interventions that addressed family violence and mental illness or substance use in LMICs identified 29 articles from 19 studies conducted in 13 LMICs. The number of studies found shows that these co-occurring problems are being increasingly addressed in diverse global settings. Moreover, 15 of the studies were RCTs, demonstrating an overall low selection bias and an expansion in the rigorous study of these co-occurring problems. Despite these advances, several gaps remain. Most studies were underpowered and did not blind to conditions reducing the quality of the evidence. None of the studies showed improvements in all intervention areas. Child maltreatment was less likely to be addressed than IPV, and few studies targeted IPV perpetration. Interventions that targeted substance and mental health mostly improved primary outcomes, but they were less effective in reducing IPV. This review shows that much work is needed for the continued development and evaluation of integrated evidence-based treatments that address family violence and related substance use and mental health problems before innovations in implementation or scale-up efforts in LMICs can occur.

Introduction

Violence is a pervasive global health problem with a cascade of physical, psychological, and social consequences accounting for 26 million disability-adjusted life years—years of life lost to illness, death, or disability (Kyu et al., Reference Kyu, Abate, Abate, Abay, Abbafati, Abbasi, Abbastabar, Abd-Allah, Abdela, Abdelalim, Abdollahpour, Abdulkader, Abebe, Abebe, Abil, Aboyans, Abrham, Abu-Raddad, Abu-Rmeileh, Accrombessi, Acharya, Acharya, Ackerman, Adamu, Adebayo, Adekanmbi, Ademi, Adetokunboh, Adib, Adsuar, Afanvi, Afarideh, Afshin, Agarwal, Agesa, Aggarwal, Aghayan, Agrawal, Ahmadi, Ahmadi, Ahmadieh, Ahmed, Hoek, Khan, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen and Vos2018). Family violence consists of physical, sexual, or psychological abuse perpetrated by one person in the household against another (United Nations General Assembly, 1993; Asghar et al., Reference Asghar, Rubenstein and Stark2017) and affects between 15% and 71% of women (Garcia-Moreno et al., Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2006) and 75% of children worldwide (World Health Organization, 2019). Two common forms of family violence include intimate partner violence (IPV; violence between partners) and child maltreatment–violence or neglect perpetrated by adults against children (Krug et al., Reference Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg and Zwi2002).

Most family violence research has been conducted in high-income countries (HICs), although overall family violence rates are higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with over 90% of violence-related deaths occurring in LMICs (Matzopoulos et al., Reference Matzopoulos, Bowman, Butchart and Mercy2008). There are multiple drivers of family violence, such as interrelated inequitable gender norms pervasive in patriarchal contexts and poverty (Coll et al., Reference Coll, Ewerling, García-Moreno, Hellwig and Barros2020; Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Annor and Kress2022). Poverty is a risk factor for IPV perpetration and child maltreatment (Skeen and Tomlinson, Reference Skeen and Tomlinson2013; Coll et al., Reference Coll, Ewerling, García-Moreno, Hellwig and Barros2020), and food insecurity increases odds of being exposed to family violence (Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Jewkes, Willan and Washington2018). Female death rates from violence increase as country income decreases (World Health Organization, 2019), and two-thirds of child deaths occur in LMICs (UNICEF, 2014). Additionally, consequences of family violence are more severe in low LMICs as compared to HICs (Garcia-Moreno et al., Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2006; Sardinha et al., Reference Sardinha, Maheu-Giroux, Stöckl, Meyer and García-Moreno2013). In LMICs, IPV is more likely to cause physical harm and involve sexual violence as compared to HICs (Garcia-Moreno et al., Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2006). Thus, it may be especially important to examine interventions that reduce family violence in LMICs.

Family violence, mental health conditions, and substance use

Given the multiple, intersecting levels in which family violence can occur, it is unsurprising that the relations among violence, mental illness, and substance misuse are dynamic with complex impacts on family systems. Exposure to family violence has been tied to mental illness, substance use, and risk for suicide (Dutton et al., Reference Dutton, Tetreault, White and Sturmey2017; Izaguirre and Calvete, Reference Izaguirre and Calvete2018) across cultures (Vizcarra et al., Reference Vizcarra, Hassan, Hunter, Muñoz, Ramiro and De Paula2010; Devries et al., Reference Devries, Watts, Yoshihama, Kiss, Schraiber, Deyessa, Heise, Durand, Mbwambo, Jansen, Berhane, Ellsberg and Garcia-Moreno2011). IPV is one of the leading risk factors for common mental health conditions among women of reproductive age (Golding, Reference Golding1999; Krug et al., Reference Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg and Zwi2002; Trevillion et al., Reference Trevillion, Oram, Feder and Howard2012). IPV impacts child mental health and substance use outcomes via the direct effect of witnessing IPV and the indirect effect of poor maternal mental health (Herba et al., Reference Herba, Glover, Ramchandani and Rondon2016; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Vigod and Riazantseva2016). Perpetration of IPV commonly co-occurs with violence against children. Child victims of violence are more likely to experience common mental conditions (depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) and substance use conditions as compared to non-exposed youth (Panyayong et al., Reference Panyayong, Tantirangsee and Bogoian2018). Childhood abuse survivors or children who have witnessed IPV have been shown to be more likely to experience and perpetrate IPV themselves, placing their offspring at higher risk (Kimber et al., Reference Kimber, Adham, Gill, McTavish and MacMillan2018). Finally, harmful substance use is a consequence of, and risk factor for, IPV (Foran and O’Leary, Reference Foran and O’Leary2008; McCloskey et al., Reference McCloskey, Boonzaier, Steinbrenner and Hunter2016).

Present study

Family violence has strong bidirectional associations with mental illness and substance use, and integrated intervention strategies are needed to sustainably reduce family violence and associated psychosocial sequelae. Yet, there is a lack of effectiveness research on integrated interventions that simultaneously address these problems. Despite the elevated need for LMICs, these settings have fewer resources to respond to family violence and related mental health and substance use conditions. Protection, such as shelters, and violence prevention resources are scarce, and violence and mental health services are typically siloed, if available. Further, there is a paucity of trained mental health professionals in LMICs that contribute to large gaps in treatment (Saraceno et al., Reference Saraceno, van Ommeren, Batniji, Cohen, Gureje, Mahoney, Sridhar and Underhill2007; Bruckner et al., Reference Bruckner, Scheffler, Shen, Yoon, Chisholm, Morris, Fulton, Dal Poz and Saxena2011). Given this reality, it is critical to consider how to treat co-occurring problems concurrently most efficiently and effectively. Therefore, this paper aims to systematically review interventions in LMICs that targeted familial violence and at least one other condition of harmful substance use or mental illness to determine effective treatments. To achieve this aim, we had two objectives: (1) describe the existing treatment evidence base and (2) identify gaps in the existing evidence.

Method

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We registered the protocol (CRD42018085229) with PROSPERO in 2018. We included studies if they described any intervention examining at least one form of familial violence and at least one mental health and/or one substance use outcome among adults or families. Interventions were operationalized as including both behavioral health psychotherapies as well as interventions that have been shown to improve mental health outcomes irrespective of specific conditions (e.g., education or financial enhancement interventions; England et al., Reference England, Butler and Gonzalez2015). Next, interventions must have been implemented in an LMIC, as defined by the World Bank (2021). Finally, we included studies that had conducted a quantitative pre- and post-assessment of outcomes, at minimum. We excluded studies that evaluated interventions targeting only children under age 18 to review studies that focused on adult perpetration of violence against partners or children, used exclusively qualitative methods, and were not published in English.

Search strategy and data extraction

Studies were identified by searching six electronic databases in 2018–2019 with no time parameters: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EBSCO-SOC Index, EMBASE, Medline/Pubmed, Ovid/PsychINFO, and PILOTS. We also searched gray literature (Edlis, Mental Health Innovation Network, mhpss.net, OpenGrey, UNICEF, and WHO Global Index), reviewed the references of key reviews, and consulted with experts for recommendations.

Standardized search terms were applied in a stepped approach. Search syntax included terms and keywords related to the following: (a) each LMIC and setting type; (b) intervention; (c) mental health or substance use condition; and (d) family violence. English language filters were applied to searches. (See online Supplementary Table 1 for a full list of search terms.)

We used a multi-step process with Rayyan’s online software database to compile and screen resulting titles and abstracts. First, three independent researchers reviewed the titles and abstracts for eligibility based on the predetermined criteria. Second, for the remaining articles, two independent researchers reviewed the full texts to determine eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus following independent screening. Third, we extracted the relevant data into a spreadsheet developed to document setting, sample, methods, intervention, measures, outcomes, and limitations. Authors were contacted for any missing or incomplete data.

Quality assessment

Study quality was evaluated using the Downs and Black (Reference Downs and Black1998) and rated on four domains: Reporting (11 items), external validity (3 items), internal validity (14 items), and power (1 item). We reported on the following criteria: (1) clear reporting; (2) randomization; (3) allocation concealment; (4) blinding of participants and personnel; (5) blinding of outcome assessors; (6) appropriate analysis; (7) valid outcome measures; (8) adequate power; (9) external validity of the sample; and (10) external validity of intervention. Two independent reviewers assessed study quality. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Results

Our search of six databases and gray literature resulted in 1514 non-duplicate articles. (See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow chart). Out of those articles, 41 were identified as potentially relevant through the title and abstract screening and proceeded to full-text review. We identified four additional articles through citation tracking and contact with authors. The full-text screen of 45 articles resulted in 13 articles being excluded. Another three were excluded during data extraction. In the end, 29 articles from 19 studies in 13 LMICs were included.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart

Characteristics of included studies

An overview of the included 19 studies can be found in Supplementary Table 2. Published between 2006 and 2019, studies were conducted in 13 countries across three continents (Africa = 11, Asia = 6, and South America = 2). Fifteen studies (79%) were randomized controlled trials. Two were pre/post without control and two were quasi-experimental.

Participants

Four studies (21%) intervened with families, either through parent–child dyads (3, 16%) or couples (1, 5%). Three studies (16%) recruited adolescents (15 and over) and adults. The remaining 12 studies targeted female adults (n = 7, 37%), male adults (2, 11%), or both (3, 16%). Sample sizes ranged from 22 to 2,776. Counting families/dyads as one participant, 15 studies (79%) had over 100 participants.

Quality assessment

All studies adequately reported details of the study objectives, procedures, and results (see Table 1). Regarding internal validity, 15 of the 19 included studies randomly allocated participants to the study conditions, reducing the risk of selection bias. However, only four studies reported whether the allocation process was concealed from participants and personnel. Lack of blinding, particularly of study participants and personnel, was the most common threat to the internal validity across studies. All studies appeared to apply appropriate statistical procedures and most reported using valid assessment tools to evaluate outcomes. Yet approximately half of the studies were underpowered or did not provide a power calculation. The external validity of the studies was generally poor. Apart from one study that screened all eligible women in the source population, participants who were recruited and/or those who were enrolled were not representative of the source population. Similarly, none of these studies evaluated interventions that are representative of services available to the source population, further limiting the external validity. We were unable to determine the external validity of the participants and/or interventions in 11 studies.

Table 1. Quality assessment

Note: Green/Y=Yes; Red/N=No; Gray/Un = Unable to Determine.

Intervention description and outcomes

Most of the interventions (n = 14) had targeted primary outcomes aimed to reduce family violence, mental health, substance use, or improve participants’ economic or HIV outcomes. These studies routinely measured reductions in symptoms on the other co-occurring problems. The remaining studies (n = n = 5) Ftested integrated interventions that explicitly addressed more than one outcome. See Supplementary Table 1 for a summary of interventions (narratively described below), Table 2 for a summary of intervention outcomes of interest, and Table 3 for a description of intervention outcomes.

Table 2. Summary of study intervention outcomes of interest

Notes: = primary outcome of interest; = measured secondarily; = not measured as intervention outcome; CM = Child Maltreatment.

Table 3. Synthesis of study outcomes

Intervention Category: Integrated = treatment focused on reduction of violence and mental health or substance use; Targeted = focused intervention to address one outcome.

Measure(s) used: primary = measured as a primary outcome of interest; secondary = measured as a secondary outcome of interest.

Target: AMD = adjusted means difference; aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio; OR = odds ratio; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; IRR = Incidence rate ratio; eOR = estimated odds ratio; RCS = residualized change score; dX = bias correct Cohen’s d; PTE = pooled treatment effect; ES = effect size not specified; NR = Not reported.

Targeted family violence interventions

Three interventions focused on family violence. Most authors analyzed IPV items with a version of the Conflict Tactics Scale. The only study to focus primarily on reducing IPV and gender-based violence (GBV), Gilbert et al. (Reference Gilbert, Jiwatram-Negron, Nikitin, Rychkova, McCrimmon, Ermolaeva, Sharonova, Mukambetov and Hunt2017) implemented a two-session “Women Initiating New Goals of Safety” (WINGS) intervention with 66 women in Kyrgystan who reported using illicit drugs or binge drinking. WINGS is an SBIRT intervention (Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral to Treatment) that incorporates IPV and GBV screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. The authors conducted a within-group analysis of pre/post assessments and observed changes in verbal and physical IPV, physical GBV, and linkage to IPV and GBV services. Reductions in sexual IPV and GBV did not occur, and verbal GBV worsened. They found significant improvements in illicit and injection drug use, but not binge drinking.

Two of the 19 studies targeted child maltreatment through parenting programs—Sinovuyo Teen (Cluver et al., Reference Cluver, Meinck, Yakubovich, Doubt, Redfern, Ward, Salah, De Stone, Petersen, Mpimpilashe, Romero, Ncobo, Lachman, Tsoanyane, Shenderovich, Loening, Byrne, Sherr, Kaplan and Gardner2016, Reference Cluver, Meinck, Steinert, Shenderovich, Doubt, Romero, Lombard, Redfern, Ward, Tsoanyane, Nzima, Sibanda, Wittesaele, De Stone, Boyes, Catanho, McLaren Lachman, Salah, Nocuza and Gardner2018) and Sinovuyo Caring Families (Lachman et al., Reference Lachman, Cluver, Ward, Hutchings, Mlotshwa, Wessels and Gardner2017)—delivered in South Africa. Both studies used standardized measures to analyze child maltreatment continuously post-treatment. Sinovuyo Teen, a 14-session program with 552 caregiver-adolescent dyads to prevent adolescent abuse, was compared to a one-day hygiene program in a cluster RCT. The program focused on improving the caregiver-adolescent relationship through time together, mutual praise, emotion management, problem-solving, and conflict management. They found reductions in abuse as reported on by youth and caregivers 1-month posttreatment and lower caregiver-reported abuse at 5- to 9-month follow-up. Five to nine months posttreatment they also showed improvements in parenting practices, caregiver depression, parenting stress, and social support, as well as caregiver and adolescent substance use. No significant changes were observed for neglect, adolescent mental health, or adolescent social support. Sinovuyo Caring Families, a 12-session, group-based program for reducing child maltreatment risk with low-income parents in Cape Town with children 3–8 years (n = 68 parent–child dyads), was compared to a waitlist control in an RCT. Sinovuyo Caring Families used behavioral parent management components to reduce maltreatment through improved parent–child relationships. No significant differences in child maltreatment were found but improvements in positive parenting were observed. Caregiver depression, parenting distress, and social support did not differ significantly across groups, nor were positive changes seen in observed and caregiver-reported child problem or positive behavior.

Targeted substance use interventions

Two interventions had substance use as their primary target. L’Engle et al. (Reference L’Engle, Mwarogo, Kingola, Sinkele and Weiner2014), Parcesepe (Reference Parcesepe2015), and Parcesepe et al. (Reference Parcesepe, Kelly, Martin, Green, Sinkele, Suchindran, Speizer, Mwarogo and Kingola2016) conducted a multisite RCT to test a six-session alcohol harm reduction (one, 20-min session a month for 6 months) intervention against a control nutrition seminar with 818 adult female sex workers who were moderate-risk drinkers in Kenya. Facilitators were nurse counselors who received training in Motivational Interviewing. Improved reductions in alcohol use consumption frequency and in binge drinking episodes were evident in the intervention group at both the 6-month and 12-month follow-up timepoints. The intervention also showed stronger reductions in verbal, physical, and sexual abuse and being robbed by clients paying for sex work services. However, there were no differences between the intervention and control in improving physical and sexual violence with non-paying (i.e., intimate) partners.

In India, Nadkarni et al. (Reference Nadkarni, Weiss, Weobong, McDaid, Singla, Park, Bhat, Katti, McCambridge, Murthy, King, Wilson, Kirkwood, Fairburn, Velleman and Patel2017a) and Nadkarni et al. (Reference Nadkarni, Weobong, Weiss, McCambridge, Bhat, Katti, Murthy, King, McDaid, Park, Wilson, Kirkwood, Fairburn, Velleman and Patel2017b) examined outcomes between Counseling for Alcohol Problems (CAP), an intervention that uses a Motivational Interviewing approach and cognitive and behavioral skills for relapse prevention, and enhanced usual care. Lay counselors facilitated CAP in three phases for four weekly 30- to 45-min sessions with 377 male adults who presented at primary healthcare centers and had harmful drinking behaviors. CAP outperformed enhanced usual care in alcohol use outcomes of remission of harmful alcohol use (AUDIT < 8) and abstinence from alcohol, although not in problems related to alcohol or drug use. No differences between the intervention and usual care manifested in physical IPV and having made a suicide attempt in the past month.

Targeted mental health interventions

Three RCTs studied the effects of interventions targeted toward mental health, showing mixed results. Most studies measured depression using structured and standardized surveys. (Chaudhury et al., Reference Chaudhury, Brown, Kirk, Mukunzi, Nyirandagijimana, Mukandanga, Ukundineza, Godfrey, Ng, Brennan and Betancourt2016) and (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Ng, Kirk, Brennan, Beardslee, Stulac, Mushashi, Nduwimana, Mukunzi, Nyirandagijimana, Kalisa, Rwabukwisi and Nyirandagijimana2017) reported findings from an RCT that examined differences between the Family Strengthening Intervention compared to social work support (treatment as usual) for HIV-positive caregivers and school-aged children ages 7–17 (n = 82 families) in Rwanda. The intervention consisted of six modules over the course of 6 months to reduce alcohol use and IPV among HIV-affected families. The authors measured IPV victimization and perpetration and alcohol use among adult caregivers (Chaudhury et al., Reference Chaudhury, Brown, Kirk, Mukunzi, Nyirandagijimana, Mukandanga, Ukundineza, Godfrey, Ng, Brennan and Betancourt2016) and mental health outcomes in children (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Ng, Kirk, Brennan, Beardslee, Stulac, Mushashi, Nduwimana, Mukunzi, Nyirandagijimana, Kalisa, Rwabukwisi and Nyirandagijimana2017). Both analyses found significant reductions of caregiver exposure to and perpetration of IPV, caregiver alcohol use, and youth and adult depression at the three-month follow-up (but not post-intervention). No differences between conditions existed for parenting, family connectedness, conduct, or functional impairment.

Patel et al. (Reference Patel, Weobong, Weiss, Anand, Bhat, Katti, Dimidjian, Araya, Hollon, King, Vijayakumar, Park, McDaid, Wilson, Velleman, Kirkwood and Fairburn2017) and (Weobong et al., Reference Weobong, Weiss, McDaid, Singla, Hollon, Nadkarni, Park, Bhat, Katti, Anand, Dimidjian, Araya, King, Vijayakumar, Wilson, Velleman, Kirkwood, Fairburn and Patel2017) conducted an RCT in India testing the Healthy Activity Programme with enhanced usual care against enhanced usual care only to reduce moderately severe to severe depression in 495 adults in primary care settings. Those randomized to the Healthy Activity Programme received 30–40-min, weekly individual sessions over 6–8 weeks consisting of behavioral activation, problem-solving, and activation of social networks facilitated by lay counselors with secondary education. Those who participated in the Healthy Activity Programme saw improved reductions in symptoms and remission of depression. Three months after enrollment, participants who received the Healthy Activity Programme reported less female victimization of physical IPV than those receiving usual care. Differences between the intervention and usual care arm in physical IPV subsided at the 12-month assessment timepoint. There were no differences in psychological/emotional IPV, combined physical and psychological/emotional IPV, or male victimization of IPV.

In Egypt, Meffert et al. (Reference Meffert, Abdo, Alla, Elmakki, Metzler and Marmar2014) tested the ability of Interpersonal Psychotherapy with 22 adult Sudanese refugees to reduce PTSD symptoms when compared to refugees in a waitlist control condition through an RCT. Nonspecialized Sudanese community therapists facilitated the therapy in a group modality twice a week for 3 weeks, adapted from the more standard 12-week duration for feasibility in a public health care and community delivery setting. Compared to the waitlist control, refugees who received Interpersonal Psychotherapy exhibited greater reductions in PTSD and state anger. There were no differences between the intervention and waitlist conditions regarding depression symptom and violence towards the household, although both were improved in the intervention condition. Differences between conditions in trait anger also did not evidence.

Targeted economic interventions

Four of the interventions aimed to improve economic outcomes. Buller et al. (Reference Buller, Hidrobo, Peterman and Heise2016) and Hidrobo et al. (Reference Hidrobo, Peterman and Heise2016) evaluated an economic intervention through the World Food Programme with a cluster RCT. The program allotted aid in the form of cash, food, or food vouchers equaling the amount of $40 to 1,226 adolescent girls and women in urban settings once monthly over the course of 6 months. They found reductions in participants’ experience of intimate partners’ controlling behaviors and physical and/or sexual violence, but no significant change in emotional violence. In addition to IPV, the authors measured internal locus of control and happiness but found no change in these mental health constructs.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Glass et al. (Reference Glass, Perrin, Kohli, Campbell and Remy2017) conducted an RCT with 833 adolescents/adults over age 16 that studied the effect of Pigs for Peace, a livestock asset transfer intervention, on victimization (girls/women) and perpetration (boys/men) of IPV, PTSD, anxiety, and depression. While they found significant reductions in anxiety and PTSD symptoms, they observed no strong changes in victimization or perpetration of IPV or depression symptoms.

Annan et al. (Reference Annan, Falb, Kpebo, Hossain and Gupta2017) and Gupta et al. (Reference Gupta, Falb, Lehmann, Kpebo, Xuan, Hossain, Zimmerman, Watts and Annan2013) studied an intervention with 934 women to improve economic development and gender equity and reduce IPV and PTSD symptoms with an RCT in rural Côte d’Ivoire. The two-armed study compared (1) a weekly Village Savings and Loans Association economic empowerment program (group of women who collectively contribute to a shared fund that individual members can borrow from with interest) only with (2) the same enhanced with an eight-session gender dialog group that additionally met biweekly over the course of 4 months. The gender dialog groups were conducted with women and their male partners to reduce gender inequalities in households. Groups were co-facilitated by mixed-gender field agents who were specialists in gender-based violence and economic empowerment. The intervention arm showed a better ability to reduce economic abuse. For couples who had high adherence to the intervention (>75% meeting attendance), the enhanced intervention arm showed significantly better reductions in physical IPV and PTSD symptoms. No differences were observed for sexual IPV.

Finally, Tankard (Reference Tankard2016) conducted an RCT with 1,800 women that examined the effects of assisting partnered women in urban settings in Colombia by opening an incentivized savings account. The intervention consisted of three free health checkups that included serology and a family planning consultation in addition to the option of opening a savings account with a contribution of 10,000 pesos ($5) and matched savings. The control condition included health checkups without the savings account option. Assessments were given at pre-intervention and nine- and 18-months post-baseline. The only difference between conditions occurred with the reduction of depression symptoms. Other mental health constructs and IPV victimization showed no differences between conditions.

Targeted HIV interventions

Two interventions targeted HIV prevention and response. Jewkes et al. (Reference Jewkes, Dunkle, Koss, Levin, Nduna, Jama and Sikweyiya2006, Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008) conducted a cluster RCT with 232 young adults in South Africa, comparing the intervention Stepping Stones to a control group session. Stepping Stones was comprised of 17 three-hour group sessions conducted over the course of 3–12 weeks. The intervention aimed to improve sexual health with a focus on gender-equitable relationships and communication through education about sexual health, sexually transmitted infections, gender-based violence, and relationships. They found that the intervention showed stronger improvements in male problem drinking at the 12-month follow-up timepoint. Other areas––physical and sexual IPV, depression, female problem drinking and drug misuse––showed no differences between the intervention and control.

Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014) facilitated a couple-based intervention called The Partner Project with 394 couples in Zambia where at least one partner had HIV. They compared intervention arms to see if there were differences according to the specialization level of facilitator. Groups led by research staff were compared to a second arm facilitated by nonspecialized community workers and a third arm that served as a control. The intervention consisted of four gender-specific group sessions that provided focused on sexual risk prevention through training and psychoeducation on negotiation and communication strategies. They found that both the researcher and community-led intervention arms outperformed the control arm in reductions of past-month IPV at the 12-month follow-up assessment. They observed no differences in extreme violence or binge drinking.

Integrated family violence, mental health, and substance use interventions and outcomes

Two interventions targeted both family violence and mental health. Both interventions reduced mental health symptoms and one improved IPV. In Kenya, Mutisya et al. (Reference Mutisya, Ngure and Mwachari2017) conducted a quasi-experimental study with 283 pregnant women in their first and second trimester who sought antenatal services in primary healthcare settings and reported experiencing any form of IPV. The psychosocial intervention consisted of psychoeducation about IPV and its effects on the pregnancy, empathic listening, and referrals for gender-based violence resources. The intervention was delivered in three 30-min sessions over the course of 5 months. Its comparison, treatment as usual, consisted of antenatal services with a list of GBV services. Benefits of the psychosocial intervention evidenced in all forms of IPV, although total and physical IPV showed the strongest effect sizes. The psychosocial intervention also demonstrated better improvements in severe combined IPV, emotional violence, and harassment than usual care. However, the effect sizes were negligible. The intervention also showed significantly stronger reductions in depressive symptoms.

In China, Tiwari et al. (Reference Tiwari, Fong, Yuen, Yuk, Pang, Humphreys and Bullock2010) conducted an RCT with 200 women who had histories of IPV. The advocacy intervention consisted of empowerment (decision-making, problem-solving, and protection) and telephone social support. To improve decision-making, facilitators provided information on cycles of violence, legal matters, and community resources so women can better recognize escalating violence to enact safety planning. The empowerment component was one 30-min session and social support entailed 12 weekly calls from a research assistant. Intervention recipients had access to the community center’s childcare, health care, and recreational services. Women in the control group received community center services without specialized violence services. The advocacy intervention had stronger effects in reducing depressive symptoms and psychological IPV and increasing social support. Differences in physical or sexual IPV did not emerge between conditions.

Two studies examined interventions that targeted IPV and alcohol use. Both interventions reduced IPV. However, reductions in alcohol use were mixed. Satyanarayana et al. (Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016) conducted an RCT in South India to test an Integrated Cognitive Behavioral Intervention (ICBI) to address IPV perpetration and alcohol use among 177 male inpatients diagnosed with Alcohol Dependence Syndrome, had a child under age 16, and had perpetrated some form of IPV in the past 6 months. The facilitators had graduate degrees in clinical psychology and were certified in ICBI. Treatment as usual included psychopharmacology and one session of psychoeducation on alcohol dependence symptoms and treatment options. ICBI encompassed eight 45–60-min sessions that addressed the relation between IPV and alcohol and identification of triggers, consequences, and prevention of IPV and alcohol. Men learned cognitive restructuring, anger management, and relaxation. There were small to medium effects of ICBI in reducing severity of IPV and depression, stress, and anxiety among the participants’ wives. Yet, no differences emerged between conditions in male alcohol use and child emotional and behavioral problems.

Witte et al. (Reference Witte, Altantsetseg, Aira, Riedel, Chen, Potocnik, El-Bassel, Wu, Gilbert, Carlson and Yao2011) and Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Chen, Chang, Batsukh, Toivgoo, Riedel and Witte2012) facilitated an RCT that tested an intervention aimed to reduce sexual risk behaviors, harmful drinking, and IPV victimization among 166 female sex workers in Mongolia. The two active treatment arms were relationship-focused and consisted of (1) four weekly group sessions that promoted knowledge and skills building for HIV and sexually transmitted illness risk reduction and (2) the first arm enhanced with two additional sessions of Motivational Interviewing. These treatments were compared to a third control wellness promotion group. All conditions effectively reduced harmful alcohol consumption (Witte et al., Reference Witte, Altantsetseg, Aira, Riedel, Chen, Potocnik, El-Bassel, Wu, Gilbert, Carlson and Yao2011) and physical and sexual IPV (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Chen, Chang, Batsukh, Toivgoo, Riedel and Witte2012). However, no differences were observed between the intervention arms and the control condition.

Finally, Jewkes et al. (Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014) targeted economic empowerment, HIV, and IPV by combining Stepping Stones (described under targeted HIV interventions) and Creating Futures, a same-sex group livelihoods intervention. Their quasi-experimental interrupted time series study occurred in two urban informal settlements in South Africa with 232 young adults aged 18 to 34. Stepping Stones was adapted to focus on HIV and violence prevention and delivered in 10 three-hour group sessions to improve communication and develop gender-equitable relationships. Creating Futures was conducted over 11 three-hour sessions and included participatory learning activities to critically reflect on current resources and how to build them. No reductions were observed in men’s perpetration of physical or sexual IPV, although women reported less sexual IPV victimization. Men showed improvements in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. However, women did not report similar gains in mental health, although they showed reductions in alcohol use. Men’s alcohol use, in contrast, did not significantly reduce.

Discussion

The objective of this systematic review was to examine interventions that targeted familial violence and at least one other condition of harmful substance use or mental illness to determine effective treatments in LMICs by describing the evidence base and identifying gaps. Nineteen studies (29 articles) out of a potential 1,514 articles from 13 LMICs met the inclusion criteria. A recent review of mental health interventions’ effects on IPV found seven studies all from middle-income countries and noted lack of representativeness of low-income countries as a critical gap (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Murray, Lund, Bolton, Murray, Davies, Haushofer, Orkin, Witte, Salama, Patel, Thornicroft and Bass2019). Thus, it appears that these co-occurring problems are being increasingly addressed in diverse settings. Moreover, 15 of the studies were RCTs, demonstrating an overall low selection bias and an expansion in the rigorous study of these co-occurring problems in LMICs.

The most substantial concerns regarding the quality of the studies were that many studies were underpowered or did not report a power calculation, lacked blinding to condition, and were not representative of the source population. In behavioral interventions, having a placebo control may not be ethical and a placebo may be more difficult to replicate with more complex behavioral interventions (Friedberg et al., Reference Friedberg, Lipsitz and Natarajan2010; Monaghan et al., Reference Monaghan, Agudelo, Rahman, Wein, Lazar, Everaert and Dmochowski2021). Likely for this reason, most of the studies in this review had usual care control arms in which blinding participants could be particularly difficult. Providers of behavioral interventions oftentimes cannot be blinded when the outcome of interest, such as symptom change, informs the course of the intervention. Blinding of outcome assessors is possibly the most critical for curbing bias since expectations can influence evaluation and inflate effect sizes. A review of 252 trials found that out of the 125 trials that assessed outcomes, only 26% reported using blinding. The use of blinding was largely dependent on use of an independent assessor (Kahan et al., Reference Kahan, Rehal and Cro2015). All these challenges are augmented in LMICs where of a lack of human resources and weak behavioral health infrastructures may be a local reality. Funding may not cover the costs of hiring an independent assessor. Office spaces are often shared, and to streamline human resources, study team meetings might consist of many team members, including research assistants who are involved in several aspects of the study, such as assessing eligibility criteria, performing outcome assessments, and randomizing participants to study arms. Where possible, it is recommended to hire an independent assessor to conduct outcome evaluations and avoid sharing study hypotheses and specific outcomes of interest, including in online study descriptions (Friedberg et al., Reference Friedberg, Lipsitz and Natarajan2010).

Interventions and measurement of outcomes varied widely. Interventions differed in duration (three weeks to two years), dose, and modality. Most studies (n = 15) had a singular intervention target. Still, there was no consistent trend of effectiveness across interventions. While implementation of evidence-based treatments with standardized follow-up timepoints and treatment durations could facilitate comparison across studies in future research, a common assertion in global mental health scale-up efforts (Bemme and D’souza, Reference Bemme and D’souza2014), there are numerous challenges to standardization. The first issue is relevance and acceptability, as local cultural contexts shape how mental health conditions are conceptualized and expressed symptomatically (Mendenhall et al., Reference Mendenhall, Yarris and Kohrt2016). In this review of studies, most interventions were theoretically informed and locally developed or adapted, which may explain the heterogeneity of outcomes regarding effectiveness. Other challenges to standardization of measurement across LMICs are that adopting and implementing new measures is costly and establishing expert consensus is difficult (Liao and Quintana, Reference Liao and Quintana2021). None of the studies showed improvements in all three areas of family violence, mental health, or substance use. Future intervention development should focus on strengthening theoretical explanations for how family violence, mental health, and substance use relate to one another and identifying core mechanisms of therapeutic action. While several authors assessed outcomes at multiple time points and follow-up, efforts were placed on understanding effect sizes rather than mediational effects. Use of path analyses in future studies could help untangle these associations further. Moreover, conducting meta-analyses to synthesize effectiveness and look more closely at factors such as intervention length and dose of sessions will be an important next step.

Outcomes for family violence also varied with few interventions improving all family violence domains. Many studies measured IPV perpetration. However, it was often unclear how interventions specifically were adapted to, or targeted, men’s perpetration of IPV. Only one study (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weobong, Weiss, Anand, Bhat, Katti, Dimidjian, Araya, Hollon, King, Vijayakumar, Park, McDaid, Wilson, Velleman, Kirkwood and Fairburn2017; Weobong et al., Reference Weobong, Weiss, McDaid, Singla, Hollon, Nadkarni, Park, Bhat, Katti, Anand, Dimidjian, Araya, King, Vijayakumar, Wilson, Velleman, Kirkwood, Fairburn and Patel2017) assessed IPV victimization among men. Globally, there is a lack of evidence-based treatments shown to be effective for reducing IPV perpetration. Research in high-income settings has shown that situational IPV––discord and conflict in couples that escalates to mild or moderate physical violence––is often bidirectional (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., Reference Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Misra, Selwyn and Rohling2012). Our research in Uganda has shown that approximately 35% of women reported perpetrating IPV towards their male partners and that perpetration was associated with victimization (authors blinded). Couple-based interventions to reduce conflict have been shown to be effective (Stith and McCollum, Reference Stith and McCollum2011) and are needed. Only one study (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014) in this review used a couple-based intervention to improve HIV outcomes. Interventions that work with the couple system are needed and may hold higher cultural relevance, given emphasis on family unity and stigma about separation (authors blinded). While many researchers employed standardized measures to assess violence, if researchers elected not to use a full standardized instrument, the rationale for selecting certain IPV items was sometimes unclear.

Child maltreatment was less likely to be addressed than IPV. Two studies (Cluver et al., Reference Cluver, Meinck, Yakubovich, Doubt, Redfern, Ward, Salah, De Stone, Petersen, Mpimpilashe, Romero, Ncobo, Lachman, Tsoanyane, Shenderovich, Loening, Byrne, Sherr, Kaplan and Gardner2016; Lachman et al., Reference Lachman, Cluver, Ward, Hutchings, Mlotshwa, Wessels and Gardner2017) in South Africa specifically aimed at reducing child maltreatment. Only one study (Meffert et al., Reference Meffert, Abdo, Alla, Elmakki, Metzler and Marmar2014) more broadly measured violence towards the household, although there is a known association between perpetration of IPV and child maltreatment (Namy et al., Reference Namy, Carlson, O’Hara, Nakuti, Bukuluki, Lwanyaaga, Namakula, Nanyunja, Wainberg, Naker and Michau2017; Mootz et al., Reference Mootz, Stark, Meyer, Asghar, Roa, Potts, Poulton, Marsh, Ritterbusch and Bennouna2019). Based on the available data presented in this review, it is difficult to make conclusive takeaways about how family violence and mental health or substance use program impact youth mental health. While the developmental literature suggests these factors––violence, maltreatment, and caregiver mental health conditions––influence the development of youth mental health conditions, the studies on IPV did not often include measures of child mental health. It is possible that if they did, improvements in child mental health would be seen. Qualitative research in Kenya has shown that intervening to reduce fathers’ alcohol use provided mental health benefits to their families (Giusto et al., Reference Giusto, Mootz, Korir, Jaguga, Mellins, Wainberg and Puffer2021). Future research should examine downstream effects of reducing IPV and adult mental health and substance use on children. On the other hand, child maltreatment studies did include measures of youth mental health yet results on mental health were mixed even with observed changes in caregiver violence. It is possible that a longer follow-up period is needed to capture potential improvements in children’s mental health. In other words, changes in the family system may take longer to influence youth mental health. Consideration of whether family-level interventions outperform couple or individual modalities could help mobilize the few resources available for mental health in low-resource settings.

Several studies in this review targeted substance use or mental health. The substance use interventions (L’Engle et al., Reference L’Engle, Mwarogo, Kingola, Sinkele and Weiner2014; Parcesepe et al., Reference Parcesepe, Kelly, Martin, Green, Sinkele, Suchindran, Speizer, Mwarogo and Kingola2016; Nadkarni et al., Reference Nadkarni, Weobong, Weiss, McCambridge, Bhat, Katti, Murthy, King, McDaid, Park, Wilson, Kirkwood, Fairburn, Velleman and Patel2017b) outperformed control conditions in reductions in alcohol use. However, no differences between conditions in IPV transpired in either intervention. Integrated substance use and IPV interventions, in contrast, showed reductions in IPV. However, one integrated intervention (Satyanarayana et al., Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016) did not observe the same reductions in alcohol use. This latter finding is surprising given that experts have concurred that there are many implementation benefits to dually addressing IPV along with comorbid alcohol misuse that include streamlined services for patients, prevention of relapse, and benefits for families and children (Mootz et al., Reference Mootz, Fennig and Wainberg2022). While the findings of this review suggest that integrated substance use and IPV interventions show trends of also reducing IPV, more effectiveness research is needed.

Targeted and integrated mental health interventions for the most part showed improvements in mental health outcomes. About half of these interventions also improved IPV. Most mental health studies focused on reduction and measurement of depression symptoms as a primary outcome of interest, although only one study emphasized meeting criteria for depression as being necessary for eligibility to participate in the study (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weobong, Weiss, Anand, Bhat, Katti, Dimidjian, Araya, Hollon, King, Vijayakumar, Park, McDaid, Wilson, Velleman, Kirkwood and Fairburn2017; Weobong et al., Reference Weobong, Weiss, McDaid, Singla, Hollon, Nadkarni, Park, Bhat, Katti, Anand, Dimidjian, Araya, King, Vijayakumar, Wilson, Velleman, Kirkwood, Fairburn and Patel2017). It was more common to explicitly include alcohol use, HIV status, or IPV as eligibility criteria and assess depression within those specialized populations. We suggest that future studies not only include their primary outcomes of interest as eligibility criteria but also consider expanding measurement and the focus of treatment to be transdiagnostic and include all common mental conditions (depression, anxiety, and PTSD). These conditions are frequently comorbid (Yatham et al., Reference Yatham, Sivathasan, Yoon, da Silva and Ravindran2018) and all have strong bidirectional associations with family violence (Trevillion et al., Reference Trevillion, Oram, Feder and Howard2012).

Moreover, studies tended to emphasize intervention effects with less systematic evaluation of implementation factors, such as scalability and sustainability. Several studies, however, implemented task-shifting, having nonspecialized providers deliver mental health care, in settings outside the traditional mental health outpatient clinic. Task-shifting can improve scale-up efforts through nonspecialized delivery of care (Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Acarturk, Bird, Bryant, Burchert, Carswell, de Jong, Dinesen, Dawson, El Chammay, van Ittersum, Jordans, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Miller, Morina, Park, Roberts, van Son, Sondorp, Pfaltz, Ruttenberg, Schick, Schnyder, van Ommeren, Ventevogel, Weissbecker, Weitz, Wiedemann, Whitney and Cuijpers2017). It can be challenging, however, to establish a proof of concept and simultaneously assess scalability and sustainability, especially for more complex, integrated interventions (Zamboni et al., Reference Zamboni, Schellenberg, Hanson, Betran and Dumont2019). Going forward, hybrid implementation-effectiveness trials can evaluate both longitudinally given that a one-time scalability and sustainability assessment conducted at the beginning of a study is not recommended (Zamboni et al., Reference Zamboni, Schellenberg, Hanson, Betran and Dumont2019). Continued consideration of how to adapt interventions to be relevant for co-occurring mental health conditions and family violence is recommended. An example of such an approach is the Common Elements Treatment Approach, a unified intervention designed for implementation in LMICs and based on evidence-based treatments for common mental conditions and substance use (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Dorsey, Haroz, Lee, Alsiary, Haydary, Weiss and Bolton2014).

Several limitations to this systematic review should be considered. While one of our main objectives was to identify effective interventions that addressed family violence and mental health and/or substance use, our search strategy did not include other related problems, such as HIV prevention and response programming, that are related and relevant in low-income settings. While the intervention terms used should have identified most studies, it is possible that our inclusion criteria of pre- and post-measurement may have inadvertently occluded violence prevention studies that focused on implementation at the community level. Next, we only included studies with abstracts in English. Finally, although we identified studies from 13 LMICs, most of these studies were concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusion

This systematic review of interventions that measured effects on family violence, mental health, and/or substance use included 19 studies (29 articles) located in 13 LMICs across three continents. Most of the studies were RCTs, were underpowered and did not blind to condition reducing the quality of the evidence. Most interventions focused on reduction of one problem (family violence, mental health, or substance use) and there was significant heterogeneity across studies. Most family violence studies focused on reducing IPV (rather than child maltreatment), and few interventions targeted IPV perpetration. Integrated substance use and IPV interventions had better success in reducing IPV than those that targeted substance use alone. About half of interventions that involved a mental health focus (mostly targeting depression) improved IPV. Future work should develop understanding of theoretical mechanisms that explain connections among these problems so that interventions can be adapted for a more comprehensive effect.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.62.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.62.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, J.M.

Author contribution

J.M.—Conceptualization, data extraction, review of articles, original draft writing; M.F.—data extraction, table construction, original draft writing; A.G.—original draft writing, risk of bias assessment; A.M.—literature search, original draft writing; C.G.—original draft writing, risk of bias assessment; M.W.—reviewing and editing.

Financial support

This project was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health K23 MH122661 and T32 MH096724, Global Mental Health Research Fellowship: Interventions That Make a Difference.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Comments

March 15, 2023

Dear Drs. Belkin, Bass, and Chibanda:

With pleasure, we submit our manuscript entitled “Interventions Addressing Family Violence and Mental Illness or Substance Use in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review” for consideration for publication in Global Mental Health.

Family violence has strong associations with substance use and mental illness. Yet, interventions that comprehensively address these related problems are lacking. Most family violence research has been conducted in high-income countries, although family violence rates are higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and outcomes more severe. To determine effective treatments in LMICs, we conducted a systematic review of interventions that addressed family violence and mental illness or substance use in LMICs, identifying 29 articles produced from 19 studies conducted in 13 LMICs. We found that none of the studies showed improvements in all intervention areas. Child maltreatment was less likely to be addressed than intimate partner violence (IPV). Targeted interventions for substance and mental health mostly improved primary outcomes, although they were less effective in reducing IPV. While advances have been made, this review shows that much work is needed to develop and rigorously evaluate evidence-based treatments before innovations in implementation or scale-up efforts for family violence interventions and related mental health and substance use problems can occur.

This material has not been published elsewhere and is not under review at another publication.

Thank you for your consideration.

Sincerely,

Jennifer Mootz and Co-Authors