How do we understand inaction in the face of overwhelming danger? Why was the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow so listless and indecisive, despite the crushing evidence of global warming? Why is the US taking major international climate accords such as the Kyoto and Paris agreements like an elective it can drop at any point? How can a petrol power’s invasion of its neighboring country trigger instant amnesia about the true causes of that and most other wars that have flared up across the globe since the 1990s? Why, at my own university, is the Hoover Institution promoting warnings against an “alarmist” approach to global warming (Lomborg Reference Lomborg2020)? It is surely not inertia that drives this sluggishness in responding to an existential crisis of planetary proportions. There has been a lot of effort and power invested in downgrading the climate emergency to a campaign waged by the so-called climate regime. There are many drivers of that effort, such as the fossil fuel industry and its money, and the military and its force. These are not isolated instances of opposition against attempts to organize a vast global response to the climate crash. While promoting their own interests, the anti–climate crisis actors are tapping into a larger narrative that has been shaping and informing the historical imagination in the industrial North over the past several hundred years.

Despite the appearance of the opposite, the Anthropocene thesis plays into, not against, this narrative. This thesis has been criticized for assigning blame for environmental degradation to an abstract “Anthropos,” providing an obvious cop-out to the industrial and imperial powers that are primarily responsible. Another way of looking at the climate crisis is by focusing on capitalism as its driving force. Jason W. Moore’s Capitalocene thesis shifts the emphasis from humanity in general to capitalism as a specific way of organizing human societies that has impacted nature in major and often irreversible ways (2015:19). This approach is not limiting the climate impact of capitalism to the last two centuries (since the beginning of industrialization), but takes the long 16th century (1451–1648) as its initial phase. Importantly for this discussion, Moore’s periodization coincides with the rise of modern drama in the West. Theatre has been uniquely effective in capturing crises, historical and intimate, small and large, and offering them for reflection and criticism of the audience: from dynastic rivalries in early modern England, to hypocrisies of the French aristocracy, to internal anguish of the bourgeois family, all the way to trench warfare, imperial conquest, and the cold war. It seems that this infinitely adaptive medium is finally reaching the limits of its effectiveness.

It has been more than a decade since the publication of Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, in which Rob Nixon called attention to the incapacity of the dominant representational order in the West to meet the challenges of the climate disaster. Violence of environmental degradation turns out to be impervious to the traditional Western aesthetic ideals of measure, harmony, and balance: this “invisible, mutagenic theater is slow paced and open ended, eluding the tidy closure, the containment, imposed by the visual orthodoxies of victory and defeat” (2011:6). On the level of the narrative, climate change verges on the unrepresentable. Una Chaudhuri and Shonni Enelow have described this impasse as no less than a “closure of representation” (2014:23). Impossible to capture in an image, or a sequence of images, or in a single narrative, the climate crisis can be glimpsed only through scientific data. The closure of representation certainly comes as a result of the very nature of climate change. But that is not the full explanation. Representation is culture-specific, and it shapes not only narratives, but also perceptions. Both mediatized representation and “naked” observation depend on mechanisms that are historically produced. The climate crisis appears unrepresentable not only because its inherent properties do not lend themselves to the widely accepted means of representation, but also because these very means of representation have been shaped by the same social forces that produced the climate crisis in the first place.

At its best, theatre creates a temporary reprieve from historical processes in which it participates, and in doing so shows them as observable and graspable events. If it seems incapable of doing that with the climate disaster, that is not because of the magnitude of that event. When it comes to climate change, the closure of representation is indicative, first and foremost, of the limits of capitalism. To question the Capitalocene is to interrogate the way capitalism imagines, produces, and uses the catastrophic closure of representation. This is not about persuasion, but about the unshackling of historical imagination. And here, this imagination pertains no less to picturing the past than to figuring the future. Not surprisingly, Mark Fisher offers the quip that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism” as the perfect summation of the idea of “capitalist realism” (2009:2), and realism extends far beyond narrative media such as theatre, film, or literature to the ways in which we picture the course of history.

Historical imagination always adopts and appropriates a certain narrative order. As Hayden White shows in Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe ([1975] 2014), the writing of history is more a poetic act than an exact science, as it often claims to be. In his seminal inquiry about historiographic writing in the West, he focuses on the period of its rapid industrialization and colonial expansion across the planet. Significantly, the universalization and naturalization of capitalism came hand in hand with the dominance of the realistic mode both in literary and historical writing. Examining the complex system of historical representation that produced several distinct forms of historical realism, White singles out three explanatory strategies as its driving forces. Each of them is subdivided in quadratarian fashion: explanation by formal argument (formism, organicism, mechanism, and contextualism); by emplotment (romance, comedy, tragedy, and satire); and by ideological implication (anarchism, conservatism, radicalism, and liberalism). More than any other, the second explanatory strategy — the one that proceeds through emplotment — depends on devices borrowed from literature, or more precisely, from drama. The Capitalocene is, indeed, a capitalo-scene.

It is the narrative, or the plot, that endows historical events with their significance and force. By identifying “the kind of story that has been told,” the explanation by emplotment endows the historical narrative with a meaning (White [Reference White1975] 2014:7). The substance and coherence of historical narrative depend not only on the succession of events, but on the internal structure of the story. Romance, comedy, tragedy, and satire received the stamp of approval in Western historiography, and the epic mode of narration didn’t because, due to its open-endedness and looseness of plot, it resembles a chronicle, which is a lower and less-developed form of historical narration (6). This, in turn, suggests an Aristotelian bias in modern historiography. White mentions Aristotle only in passing, and he certainly doesn’t draw on the Poetics in establishing his four kinds of emplotment.Footnote 1 However, he very much relies on the Aristotelian idea of the dramatic plot defined by its coherence, proportionality, and closure. Aristotle presents dramatic emplotment in the most logical way imaginable, as a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end. He defines beginning as “that which does not have a necessary connection with a preceding event, but which can itself give rise naturally to some further fact or occurrence”; “the ‘middle’ involves causal connections with both what proceeds and what ensues”; finally, the end “is something which naturally occurs after a preceding event, whether by necessity or as a general rule, but need not be followed by anything else” (in Halliwell Reference Halliwell1987:39). The very fact that White doesn’t delve into an analysis of Aristotelian emplotment suggests that the idea of dramatic narrative outlined in the Poetics has the degree of obviousness that makes it one of the cornerstones of Western culture.

There is a certain discrepancy between White’s analysis of historiography and his analytical tools. The forms of emplotment he is using — romance, tragedy, comedy, and satire — are not representative of the period he is discussing, but can be traced back precisely to the long 16th century. According to White, one of the key differences between historical writing of the 19th century and the periods that preceded it is its academization ([1975] 2014:19). He fails to mention that the same applies to the discourse of drama during that same period. However, theatre brings into sharper contrast one of the key aspects of academization that is not as easily observable in historical writing: its entrance into the academy went hand in hand with its industrialization. The key transformation in the long 19th century of the modes of emplotment that had emerged in the long 16th century was in the ways they were systematized. That systematization was the function of their mode of deployment. In an industrial society, a poetic imagination does not suffice: what is called for is a set of learnable and reproducible instructions. The academization of playwriting was inseparable from its commodification. The first American playwright to make a living from his art was Bronson Howard in the 1870s, and the first playwright who became a millionaire was Clyde Fitch in the 1890s (Arnett Reference Arnett1997:25, 28). This coincided with the publication in 1890 of the first American playwriting manual The Art of Playwriting by Alfred Hennequin, followed by William Thompson Price’s The Technique of the Drama in 1892 and by Elisabeth Woodbridge Morris’s The Drama: Its Law and Its Technique in 1898. Hennequin offered the first classes in playwriting at the University of Michigan in the 1870s, and Howard lectured at Harvard in 1885. Stephen Weeks notes that George Pierce Baker, who went on to write the influential Dramatic Technique (1919), attended Howard’s Harvard lecture. In 1905, he started offering his class English 47, The Technique of Drama, at Harvard, which he then took to Yale in 1925 (Weeks Reference Weeks, Susan, Geoffrey and Lupu1997:390). Even this cursory survey shows that industrialization and the academization of drama were marked by the shift in emphasis from poetics to craft. In their championing of technique, the American authors of playwriting manuals followed the example set by German novelist and playwright Gustav Freytag and his Die Technik des Dramas (1863). By far his most influential publication, Freytag’s book went quickly through six German editions, and was soon translated and published across Europe. It received its first US edition in 1894.

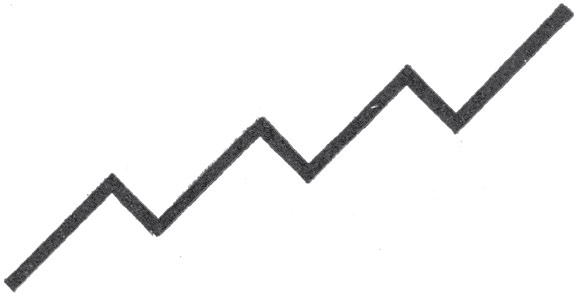

The Aristotelianism of the industrial age is a narrative practice appropriated by capitalism and elevated, through its imperialist routes, to the position of universality and inevitability. This streamlining of Aristotelian narrative by industrial capitalism received its iconic image in Freytag’s graph of the dramatic action in the form of a pyramid (fig. 1). Most of the famous “Five Parts and Three Crises of the Drama” from his pyramid schema are geared towards the dynamics of growth. While claiming the mantle of Aristotelian tradition, Freytag replaces his simple notion of the beginning with “rise” or “ascent,” a property of tragedy barely mentioned in the Poetics. “The exciting force” pushes the action forward, and “the rising movement” gives it a definitive upward direction ([1863] 1908:125). Speaking of dramatic action, Freytag writes that “the poet must continually heighten his effects from the beginning to the end of the play” (79). The upward movement is paramount: the playwright “must see to it, that the performance becomes gradually greater and more impressive” through careful organization of “heightening effects” (80). Expansion and enlargement are the central imperatives of both dramatic and historical narratives of the industrial age. The task of a dramatist is no different from the task of an entrepreneur: “the scenes of this rising movement […] have to produce a progressive intensity of interest; they must, therefore not only evince progress in their import, but they must show an enlargement in form and treatment […]” (128; emphasis added). This powerful upward movement leads to the point of climax, and that’s where the problems start. It is no wonder that according to Freytag’s doctrine, “the most difficult part of the drama is the sequence of scenes in the downward movement” (133). While the logic of growth and upward movement seem perfectly rational in a society guided by them, the opposite movement appears much harder to rationalize and implement.

Figure 1. Gustav Freytag’s graph from his Die Technik des Dramas ([1863] 1908). Here, “a” designates introduction, “b” rise, “c” climax, “d” return or fall, and “e” catastrophe.

Freytag attempts to preserve the symmetry of his dramatic structure by devising additional plot elements on the right side of his graph. The “downward compelling force” dominates the “d” side of the diagram: there is no going back after the climactic point, and one last complication can only intensify the final catastrophe. The third and final “crisis” occurs before the conclusion of the play. “The force of the final suspense” is a pause in the “downfall” or the “return” that prepares the finale (135). Freytag leaves no doubt that the end of drama can come only as utter devastation and death: “the poet should not allow himself to be misled by modern tender-heartedness, to spare the life of his hero on the stage” (137). According to him, the catastrophe brings the action to a complete stop: “the drama must present an action, including within itself all its parts, excluding all else, perfectly complete” (138). Freytag’s catastrophe is a complete and utter collapse of the tragic protagonist’s life and an irreconcilable termination of its story. Having ascended and grown, the action seems to slide inevitably toward its demise. The plot is the scheme of the ascent and descent that mirror one other.

Freytag’s followers and commentators observed early on that the perfectly symmetrical pyramid is an idealization of the dramatic plot, and that in playwriting practice the climax most often does not come in the middle of the play but towards its end. This results in a “return” that is short and speedy rather than protracted and symmetrical to the “rise.” The pyramid is, in fact, not an equilateral but a right scalene triangle. In his influential Play-Making: A Manual of Craftsmanship, William Archer ascribed this asymmetry of modern drama by the prevalence of the three- as opposed to the five-act structure in Freytag’s literary models ([1912] 1960:123). Still, these adjustments are pedantic, and they leave the catastrophe, or as Archer would have it, “the full close” intact. It seems that it is at this point that the historical realism of the industrial age parts ways with its fundamental mode of emplotment.

In order to become a commodity, a narrative has to adapt itself to the capitalist rules of production. These rules, as Moore observed, embody a “value relation”; in other words, they determine “what counts as valuable and what does not” (2015:174). In Freytag’s schema, the rules of growth and suspense clearly adhere to and promote capitalist value relations. The pyramid departs from them in its emphasis on the finality of the catastrophe. One of the main properties of capitalist civilization is its ability to absorb its criticisms, however radical they might be, and use them for its benefit. Here, “criticism” is a broad term that includes crises of catastrophic proportions: capitalism survived the disasters of slavery, of colonialism, of economic crashes, of fascism and Nazism, of uprisings and revolutions, of deindustrialization, and even, for the time being, of the nuclear age. Not only did it not collapse in all of these catastrophes, but it steadily expanded and grew. The problem with Freytag’s graph is not in its symmetry but in its failure to allow for the possibility of that ever-rising growth. When it comes to historical imagination, triangular emplotment can account for isolated periods. It facilitates fragmentary narratives of rises and falls, starts and stops, booms and busts. More than anything else, with its finality, this model offers a historical narrative deprived of the projection into the future. It appears utterly unsuited for the depiction of historical progress seen as economic expansion, and thus unable to offer a realistic self-representation of industrial capitalism. Or, to use White’s terminology, it diverges radically from the predominant ideological dimension of the era for which it speaks.

If Freytag’s dynamic model of emplotment was successful in promoting a new form of dramatic composition, how is it possible that it missed the grand narrative of capitalism? Better yet, to what degree did it diverge from it? The answer to this question and a major revision of Freytag’s schema came from one of the least expected places: the Soviet Union of the 1920s. In his textbook Dramaturgy, initially published in 1923 (reprinted in 1929 and 1937, with expanded editions in 1960 and 1969), playwright and theatre scholar Vladimir Mikhailovich Volkenstein offered a new interpretation of dramatic emplotment.Footnote 2 While Freytag relied on examples from the classics of Western dramatic canon, Volkenstein’s approach was informed by his decade-long (1911–1921) engagement as a literary adviser in the Moscow Art Theatre, where he was one of Konstantin Stanislavski’s close collaborators. In his comments on Freytag, Volkenstein notes that his diagram “pertains only to the genre of tragedy, and has no wider relevance” ([1923] 1966:20). Further, he objects to the absence of the consideration of “complication” from Freytag’s schema, and notes a certain relativism in his usage of categories. Still, his main objection concerns Freytag’s (mis)-understanding of the catastrophe:

Until now, the idea of dramatic “catastrophe” has not been the subject of analysis. The term “catastrophe” is used in two senses. If the dramatic process is seen as a development of the hero’s fate, then in a tragedy the catastrophe necessarily comes at the end, but if we look at the process in its totality, which is to say as the process of a conflict in a certain social setting, then the catastrophe for that setting, or the group of people, will be the moment of the hero’s disturbance of that social unit, the moment of his decisive and sharp action in the emerging conflict. In that case, the catastrophe will not be the finale of the tragedy, but the moment that precedes, sometimes by far, the finale, or the denouement of the tragedy; in a four- or five-act drama, the catastrophe often comes at the end of the third act. ([1923] 1966:20)

And not only that: more often than not, in modern drama there are multiple “catastrophes” that don’t end but propel the action. The catastrophe does not represent a finality, but a temporary retreat, a recoil, that helps the dramatic action gain traction and spring forward. This reconfiguration of the catastrophe allows Volkenstein to replace Freytag’s closed triangle with the ascending steps diagram (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Volkenstein’s alternative to Freytag’s triangle. From Dramaturgija ([1923] 1966).

Volkenstein’s refiguration of the catastrophe not as a final but a provisional breakdown is informed not only by his analysis of dramatic plots, but also by his lived historical experience. It is important to keep in mind that his book came out in the first years after the October Revolution, which was widely perceived as a historical catastrophe. In the introduction, Volkenstein expresses his full awareness that the “Soviet dramatist” is addressing a “serious spectator, who experienced dramatic disturbances, and who is a participant of grand historical events and a builder of a new culture” (5). What the revolution brought was not a rejection, but an intensification of industrial production. As it turned out, the capitalist mode of production survived October: save for the first period immediately after the revolution, one of the key changes that this crisis accomplished was to shift the ownership of the means of production from private hands to the state. Volkenstein depicted with great precision not only the historical emplotment of capitalist modernity, but the main mechanisms it uses to sustain and expand itself. The first mechanism involves the reconfiguration of the very idea of the catastrophe from an all-out apocalypse to a stage in historical development. Any crisis that does not destroy capitalism will only make it stronger. Capitalism not only absorbs crises, but actively produces them and grows through them. The second mechanism explains the functioning of the first one. Volkenstein’s inversion of the dramatic perspective suggests that the mechanism by which capitalism survives its catastrophes is through their socialization. The amortization of the catastrophe is made possible by its horizontal distribution throughout the society, be it a microcommunity of dramatic characters onstage or an entire nation or, as in the case of the Anthropocene, all of humanity, from the beginning of history. It is this form of emplotment that modern drama shares with the historical imagination that dominates industrial modernity, from corporate drawing boards of liberal capitalism to planning commissions of state capitalism.

Volkenstein’s ascending steps diagram can help us understand the strategies that capitalism uses in the ways in which it addresses climate change. Its proven strategy is to recast the epochal catastrophe into a developmental crisis. Seen as yet another crisis (that of climate), global warming suddenly becomes an opportunity for the development of new green technologies. By not taking a decisive action, the leaders of the industrialized world are socializing the very crisis they are producing. We are asked not to panic about climate change, but to get used to it as a new regime of production. This time, socialization reaches the broadest possible dimensions. The planet is too big to fail. The greater the risk, the higher the profit. What climate entrepreneurs don’t want to see is that this time around, the developmental crisis might indeed be the epochal catastrophe. This has to be the starting point of new narrative strategies in theatre and outside of it. One of the things that the industrial age, greedy for growth, irreparably corrupted in its march to “prosperity” is the Aristotelian narrative. It is spoiled beyond repair. Epic or any other form of non-Aristotelian theatre no longer suffices. Instead, what we need is the questioning and systematic dismantling of all of Aristotelian theatre’s components, however commonsensical, necessary, or obvious they may appear. Or, precisely those that seem most obvious and indispensable.