The Lothagam harpoon site in north-west Kenya's Lake Turkana Basin provides a stratified Holocene sequence capturing changes in African fisher-hunter-gatherer strategies through a series of subtle and dramatic climate shifts (Figure 1). The site rose to archaeological prominence following Robbins's 1965–1966 excavations, which yielded sizeable lithic and ceramic assemblages and one of the largest collections of Early Holocene human remains from Eastern Africa (Robbins Reference Robbins1974; Angel et al. Reference Angel, Phenice, Robbins and Lynch1980).

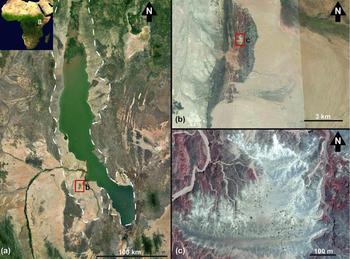

Figure 1. Location of Lothagam Lokam; a) Lake Turkana, dashed line marks Early Holocene lake maximum; b) location of the Lothagam ridges; c) specific location of Lokam palaeo-beach.

The recovery of hundreds of barbed bone points (‘harpoons’) linked Lothagam to what Sutton (Reference Sutton1977) called the ‘Aqualithic’—a material cultural tradition focused on aquatic resources during the African Humid Period (c. 12000–5000 BP), a period when mega-lakes, riverine systems and grasslands expanded across the Sahara and Eastern Africa (Kuper & Kröpelin Reference Kuper and Kröpelin2006). Stratified within shell beds, beach sands and gravels, Lothagam's artefact horizons reflect human activities during the African Humid Period, which was followed by a period of intense desiccation that reduced lake levels by ~50 per cent (Bloszies et al. Reference Bloszies, Forman and Wright2015). Despite the importance of the site for understanding eastern African lifeways during the Holocene, methods available in 1965–1966 could not pinpoint precise relationships between climatic shifts, changes in cultural material and mortuary practices.

Following a meeting with Robbins in 2016, the authors organised new fieldwork at Lothagam with the goal of exploring these relationships by placing the results of his excavations into a more secure chronological and palaeoenvironmental framework. In June 2017, we returned to the field. Our initial goal was to expose and sample geological profiles spanning the Early Holocene shell beds to the uppermost sands, which were probably deposited near the end of the African Humid Period. Targeted excavation units helped connect our geological sections to the archaeological strata identified by Robbins (Reference Robbins1974). A second goal of bioarchaeological salvage excavations emerged after we identified human remains eroding from archaeological deposits. These excavations recovered several of the burials most at risk from disturbance, and we documented more than 30 additional locations where remains are partially exposed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Example of human burial exposed on surface (a), and during recovery in 2017 (b); much of the lower torso had already been lost to erosion.

As numerous archaeological and palaeontological sites have been found around Lothagam since 1974 (e.g. Leakey & Harris Reference Leakey and Harris2003; Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand, Shea and Grillo2011), we hereafter refer to this specific site area as ‘Lothagam Lokam’, using the Turkana word for its characteristic white sands rich in shells. Here, we briefly report on the preliminary results of our 2017 field season.

Lothagam Lokam

During the early Holocene (c. 11000–8000 BP), Lothagam's two massive basalt ridges formed a peninsula along the shores of an enlarged Lake Turkana that trapped both lacustrine and aeolian sediments, forming a narrow beach ridge (Figure 3). In the past, there would have been a sheltered lacustrine cove to the north of this beach and an impermanent back-water swamp to the south. Abundant archaeological deposits signal that people continuously used this location throughout the Holocene.

Figure 3. View of Lokam from the east Lothagam ridge in 1965 (left) and 2017 (right).

We relocated Robbins's original excavations using photo-comparisons, drone imagery and surface inspection. Geological trenches placed nearby revealed a complex, detailed picture of Holocene palaeo-lake fluctuations in Turkana (Figure 4). Stratified gravel and sand beds record multiple phases of Holocene lake transgression and regression, while minute variations in sediment grain size indicate a constantly changing shoreline. Combined with new radiocarbon and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) samples, our sediment analysis will help to establish a refined chronology for numerous environmental changes that fisher-hunter-gatherers around Turkana faced throughout the African Humid Period.

Figure 4. Cleaning a geological profile on the north end of the Lokam palaeo-beach.

We placed two new trenches (one of 1 × 2m, one of 1 × 3m) to probe the geological and archaeological sequences across the site. Excavations reached 0.6–0.9m below the ground surface and produced lithic assemblages made from local basalts and cherts, as well as small quantities of non-local obsidians, agate and quartz. Faunal remains show a mix of lacustrine and terrestrial resources, consistent with the original excavations (Robbins Reference Robbins1974). We encountered undecorated ceramics in situ, but we observed surface scatters dominated by wavy line and dotted wavy line motifs associated with Saharan African Humid Period ceramic traditions (Figure 5). Similarly, we found dozens of barbed bone points on the surface but few during excavation.

Figure 5. Example of dense scatters of bone, lithic artefacts and barbed bone points on the surface of Lothagam Lokam.

Preliminary data from renewed investigations at Lothagam Lokam suggest that a rapid drop in lake levels and increased aridity beginning in the Middle Holocene challenged longstanding strategies of small-scale, fisher-hunter-gatherer communities, as identified by the work of Stewart (Reference Stewart1989) and others. Responses to these changes, both at Lothagam and more broadly around Lake Turkana, must have been at least partially conditioned by previous economic and social responses to previous, less severe, fluctuations in Holocene climate. Our ongoing research at Lothagam Lokam will continue to explore these questions and illuminate the strategic flexibility of Holocene fisher-hunter-gatherers in Eastern Africa.

Acknowledgements

Fieldwork was made possible by the generous assistance of the Turkana Basin Institute and the communities of Kerio and Lothagam in Turkana County. We are especially grateful to Purity Kiura and Emmanuel Ndiema of the National Museums of Kenya for facilitating research. Local crew members Alex Ekutan and Mariko Ekaale were instrumental in field data collection. We also thank the TBI Field School students whose participation greatly benefitted the project. Research was carried out under NACOSTI permit NACOSTI/P/17/4316/16668. This research was funded by Wenner-Gren Foundation Grant 9410.