Introduction

In current geologic-repository concepts, high-level spent nuclear fuel will be placed in metallic canisters, separated from the host rock by compacted bentonite (i.e. a type of swelling clay) referred to as a ‘buffer’. Copper was chosen in the Finnish and Swedish concepts for the outer shell of the spent fuel canisters because of its high resistance to corrosion under anaerobic conditions (Reference King and LiljaKing & Lilja, 2014; Nagra, 2002). Nevertheless, this material is sensitive to corrosion by sulfide ions (Reference Kong, Dong, Ni, Xu, He, Xiao and LiKong et al., 2017). Sulfate reduction by sulfate-reducing bacteria is generally considered to be the main source for sulfide. Sulfide production can occur in groundwater, at the interface of the high density (compacted) clay with the host rock or within the host rock (Reference Bengtsson and PedersenBengtsson & Pedersen, 2016), or even within the bentonite barrier if the density is low enough (Reference Grigoryan, Jalique, Medihala, Stroes-Gascoyne, Wolfaardt, McKelvie and KorberGrigoryan et al., 2018; Reference Masurat, Eriksson and PedersenMasurat et al., 2010a; Reference Pedersen, Bengtsson, Blom, Johansson and TaborowskiPedersen et al., 2017). The production of sulfide in the vicinity of the canisters or the transport of sulfide from adjacent groundwater to canisters may induce significant sulfide fluxes to the canisters, thereby decreasing their lifetime. Such production has been shown to be possible, although limited by compaction of the bentonite buffer material (Reference Bengtsson and PedersenBengtsson & Pedersen, 2016, Reference Bengtsson and Pedersen2017; Reference Grigoryan, Jalique, Medihala, Stroes-Gascoyne, Wolfaardt, McKelvie and KorberGrigoryan et al., 2018; Reference Masurat, Pedersen, Oversby and WermeMasurat & Pedersen, 2004; Reference Masurat, Eriksson and PedersenMasurat et al., 2010b; Reference Pedersen, Motamedi, Karnland and SandenPedersen et al., 2000). Furthermore, bentonites have also been found to react to some extent with sulfide, and an immobilization capacity of 30–40 mmol kg–1 of bentonite has been estimated recently (Reference Pedersen, Bengtsson, Blom, Johansson and TaborowskiPedersen et al., 2017; Reference Svensson, Lundgren and WilkbergSvensson et al., 2017).

Bentonites have been used as H2S gas scrubbers in various industrial and mining applications for > 30 y (Reference Stepova, MacQuarrie and KripStepova et al., 2009). The immobilization of sulfide by bentonite involves a redox interaction with iron present in smectite (structural Fe, Festr) and also in Fe (oxyhydr)oxides, present as accessory minerals. On the one hand, the interaction between Fe (oxyhydr)oxides and sulfide has been studied for the last four decades (Reference Dos Santos Afonso and StummDos Santos Afonso & Stumm, 1992; Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015; Reference Poulton, Krom and RaiswellPoulton et al., 2004; Reference RickardRickard, 1974). On the other hand, the ability of reduced sulfur-bearing species to reduce Festr in clays has been known for > 50 y, and has been used widely in research on the redox properties of Festr (Reference Stucki, Bergaya, Theng and LagalyStucki, 2006a). The vast majority of these studies have focused on the impact of the redox process on the clay sample (rarely on the sulfidic reducer) and also generally used dithionite instead of sulfide. Despite the numerous studies devoted to this topic, little is known about the underlying reduction process and its limitations, the identity of the oxidized sulfur-bearing species, and the global effect on clay properties.

To date, only one study has reported one data point on one sample relative to the extent of Festr reduction achieved in an Fe-rich pure clay (nontronite SWa-1) using a concentrated sodium sulfide solution (Reference Gan, Stucki and BaileyGan et al., 1992). This previous study inferred a sulfide immobilization capacity of at least 180 mmol kg–1 for this nontronite. No data are available for montmorillonites (the main Fe constituent in most bentonites), or for commercial bentonites. The few studies of sulfide–bentonite interaction under repository conditions published so far (Reference Pedersen, Bengtsson, Blom, Johansson and TaborowskiPedersen et al., 2017; Reference Svensson, Lundgren and WilkbergSvensson et al., 2017) employed low-sulfide concentrations, which generally resulted in complete consumption of sulfide. The disadvantage of these studies is that the concentrations of oxidation products and the impact on the clay material were too low to be quantified or even detected in some cases.

The goal of the present study was to overcome these issues by employing significantly higher sulfide concentrations in the batch experiments. Excessive sulfide concentrations (relative to available Fe pools) were used to measure residual concentrations of sulfide after interaction with the samples. The aim was also to maximize the impact on the bentonites and determine the maximum extent of sulfide consumption. Investigated samples included six natural bentonites with a range of composition, purified Fe-bearing components commonly found in those bentonites (mainly montmorillonite and accessory Fe (oxyhydr)oxides), and a synthetic blend of pure montmorillonite and goethite. These various series of samples were in contact with concentrated solutions for periods of 1 h to 1.5 months under anaerobic conditions and at pH conditions between 7 and 13. Sulfide concentration was measured colorimetrically. The major detectable product in solution (polysulfide) was also determined colorimetrically. The impact on the solid sample regarding iron speciation (i.e. the extent of reduction of Fe and structural localization) was determined by 57Fe transmission Mössbauer spectrometry.

Materials and Methods

Anaerobic Conditions

All experiments were prepared and sampled in a glovebag with a 95:5 N2:H2 atmosphere equipped with two palladium catalyst scrubbers (Coy Laboratory Products Inc., Grass Lake, Michigan, USA). The ultrapure Milli-Q® water was degassed by bubbling with N2 for a minimum of 2 h and then exposed to the atmosphere of the anaerobic chamber for a minimum of 1 day. The materials studied were also exposed to the atmosphere of the anaerobic chamber for a few weeks prior to use.

Materials Studied and Chemicals

All samples studied and chemicals used are listed in Supplementary Material Table S1. Fe (oxyhydr)oxides (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and two pure montmorillonite samples (PGV and PGN, Nanocor Inc., Aberdeen, Mississipi, USA) were used as purchased. The other montmorillonite samples were first fractionated to < 2 μm by the elutriation technique (Reference YamamotoYamamoto, 2000), either Na- or Ca-saturated, and freeze-dried before use. The mineralogical purity of the clay samples was checked by X-ray diffraction (XRD, data not shown), X-ray fluorescence (XRF, Table S2), and Mössbauer spectrometry (all data given in the Supporting Information document). Only the montmorillonite GeM (purified by the author from bentonite GeoB supplied by A-Insinöörit Oy, Tampere, Finland) still contained detectable Fe-bearing impurities (accounting for 7–9% of total Fe, i.e. < 0.2 wt.%) which could not be identified clearly (Fig. S8 and Table S8). The montmorillonite SWy (CMS Source Clays, Chantilly, Virginia, USA) was also deemed to contain a greater proportion of illitic layers than the other samples, mainly based on its initially large proportion of structural Fe2+ and interlayer potassium (Reference Meunier and VeldeMeunier & Velde, 2004). On the basis on their structural formula (Table S3, derived from XRF analysis), the montmorillonites studied can be classified into two categories: ‘Wyoming’ versus ‘Chambers’ montmorillonites (according to the classifications of Reference Grim and KulbickiGrim and Kulbicki (1961) and Reference SchultzSchultz (1969), based on octahedral composition, with similar Fe content in both types, but larger Mg content in the Chambers type).

The natural bentonites studied (supplied either by A-Insinöörit Oy or by SKB, Solna, Sweden) are from the Czech Republic (CzeB), India (IndB), Italy (ItaB), Georgia (GeoB), Greece (GreB) and USA (WyoB). The bentonite samples were crushed by hand in an agate mortar and sieved (500 µm). One synthetic bentonite was produced by mixing 20 g of purified SWy with 200 mg of goethite. Raw bentonites showed contrasting mineralogical composition, especially regarding Fe-bearing phases (Table S4). The two Fe-richest bentonites (Czeb and IndB) contain about equivalent proportions of Fe in both clay structure (Festr) and in accessory minerals (Feacc, mainly goethite with some hematite). ItaB contains a smaller but still notable proportion of Feacc (mainly hematite). A variety of Fe-bearing accessory minerals was also found in the Fe-poorer WyoB using SEM and Raman spectroscopy (Reference Hadi, Wersin, Jenni and GrenecheHadi et al., 2017; Reference Wersin, Hadi, Jenni, Svensson, Grenèche, Sellin and LeupinWersin et al., 2021), but Mössbauer and XRD data showed that those minerals are present only as traces. This may also be true of GreB, but no SEM or Raman data are available to confirm this. GeoB displays a composition similar to GreB, with a moderate Fe content and a large smectite content. The clay component is probably similar in GreB and GeoB (similar color, clay composition, and cation exchange capacity (CEC)). Still, a small portion of a superparamagnetic Fe (oxyhydr)oxide could also be detected in GeoB with Mössbauer spectrometry (2–5%, Fig. S23 and Table S17).

Batch Experiments

All experiments were carried out in 35 mL polysulfone (PSF) centrifuge tubes (Nalgene™ Oak Ridge centrifuge tube, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland). The liquid-to-solid (L/S) ratio was set in order to operate with sufficient mass of both the solid sample and solution for final collection and characterization. The starting sulfide concentration was adjusted according to the total amount of iron present in the reaction tube in order to, ideally, have twice as much sulfide as required to reduce all the Fe, assuming two electron transfers (Half-cell redox reactions Eqs. 1 and 2).

In the case of clay, Festr was expected to remain in the clay octahedral structure (Reference Hadi, Tournassat, Ignatiadis, Greneche and CharletHadi et al., 2013; Reference Stucki, Golden and RothStucki et al., 1984). An analogous mechanism was envisioned in the case of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides (following Dos Santos Afonso & Reference Dos Santos Afonso and StummStumm (1992), Reference Poulton, Krom and RaiswellPoulton et al. (2004), and Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al. (2015)), where one mole of sulfide would reduce two moles of Fe3+, but would also be accompanied by dissolution of the sample, release of Fe2+, and possible further precipitation as FeS- bearing compounds, such as mackinawite and/or recrystallization of the Fe (oxyhydr)oxide substrate.

Concentrated reacting solutions of 4–250 mM Na2S were first prepared. NaCl was also added to establish similar ionic strengths in all experiments (100 mM or 250 mM total Na in experiments with clays or Fe (oxyhydr)oxides and Fe-rich bentonites, respectively). A few experiments used unbuffered sulfide solutions (basic pH, i.e. pH > 13). Otherwise, the pH was adjusted to ~8 through the dropwise addition of a dilute 0.6 mM HCl solution. All experiments were prepared gravimetrically. The solid sample was first introduced into a tared tube. The volume of reacting solution was then adjusted to obtain the desired L/S ratio. The tubes were stirred using a rotating shaker. After a given reaction time, solutions were centrifuged (8–15 min at 28,408 × g) outside the anaerobic chamber and reintroduced carefully into the anaerobic chamber. The supernatants were collected (half the volume filtered to 0.2 µm, and the remaining part kept unfiltered). The solid was freeze dried outside of the anaerobic chamber. Anaerobic conditions during transfer between the anaerobic chamber and the vacuum freeze-drying chamber were ensured by placing the sample in a vacuum sealable jar. Most investigated bentonites samples were reacted in two batch experiments lasting 24 h and 1 month. Two bentonite samples (WyoB and Syn-Mix) were reacted in a more time-resolved manner (ten experiments per material, lasting for 1, 2, 4, 12, 24, 48 h, and 1, 2, 3, 4 weeks).

Sulfide Analysis

Sulfide analyses were carried out using a modified methylene blue (MB) colorimetric method (Reference ClineCline, 1969; Reference Reese, Finneran, Mills, Zhu and MorseReese et al., 2011). The diamine reagent was prepared outside the anaerobic chamber by dissolving 100 mM of FeCl3 first and then 100 mM N–N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulfate in 6 N HCl. This solution was then introduced into the anaerobic chamber and exposed to its atmosphere for 1 h while stirring. All samples were treated in the same way as the standard solutions. The first step of dilution was carried out in the glove box. The amount of sample (0.44–5 mL) was determined gravimetrically by introducing it into a 50 mL flask half filled with deionized water (placed on a scale). Then a fixed volume (5 mL) of diamine reagent was added, the flask was filled to the volume mark with pure water and closed. At least 30 min after color development, a second dilution of 60–65 µL of sample in 4 mL of pure water was performed gravimetrically outside the glove box. This sample was then analyzed by colorimetry (absorbing wavelength 671 nm), and its pH was measured. The sample and standard preparation were carried out so that narrow ranges of pH (2.00–2.20) and probe concentrations were achieved following the two-step dilution, and thus within a small absorbance range (0.70–0.85). Along with each series of measured samples, a 90 mM Na2S solution at high pH (pH ~13) was used as a control sample for the duration of the study (1 y). Measurements were considered valid when the uncertainty in the determination of its concentration was ± 2% of the nominal value (Fig. S2).

Polysulfide Analysis

Elemental sulfur is produced as a result of the oxidation of sulfide (Reference Peiffer, Dos Santos Afonso, Wehrli and GächterPeiffer et al., 1992; Reference PoultonPoulton, 2003; Reference Poulton, Krom and RaiswellPoulton et al., 2004; Reference Pyzik and SommerPyzik & Sommer, 1981) (Eqs. 1 and 2), and, it can react further with sulfide to form polysulfide (Reference Steudel and SteudelSteudel, 2003) which yields a strong yellow coloration to solutions (Eq. 3).

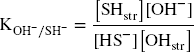

A simple, direct colorimetric method was applied to the analysis of polysulfide (Reference GiggenbachGiggenbach, 1972; Reference Pyzik and SommerPyzik & Sommer, 1981). The calibration of the method was based on the sulfide consumption measured in synthetic solutions of sulfide and elemental sulfur produced under conditions similar to those observed in the experiments (excess sulfide, pH between 8 and 13, see Supporting Information). An aliquot of the supernatant of the final sample was diluted with pure deoxygenated water inside the anaerobic chamber. The diluted solution was then placed in a cuvette, which was capped (Elkay Laboratory Products Ltd, Basingstoke, UK) prior to be being removed from the anaerobic chamber. The solution was analyzed within 20 min, scanning the entire visible spectrum. The absorbance at 371 nm was used for quantification, using the calibration curve established at pH 8–9 (Fig. S2).

57Fe Mössbauer Spectrometry

Sample preparation was performed in the anaerobic chamber. An aliquot (80–400 mg depending on the iron content) was sealed in a small poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) cup, using degassed araldite resin. The Mössbauer spectra were recorded at room temperature (RT, 300 K) and in many cases also at 77 K, using a constant acceleration spectrometer (driving unit supplied by WissEl GmbH, Starnberg, Germany) and a 57Co source diffused in a rhodium matrix. The transducer was calibrated using an α-Fe foil at RT. The values of the hyperfine parameters were refined using the unpublished MOSFIT least-squares fitting procedure (by Varret & Teillet, Le Mans Université, France) with a discrete number of independent quadrupole doublets and magnetic sextets composed of Lorentzian line shapes. The values of isomer shift (IS) are quoted relative to that of the α-Fe spectrum obtained at RT. The relative proportions of each Fe species were derived from their relative spectral area. Indeed, the f-Lamb-Mössbauer factors (recoil-free fraction), which corresponded to the fraction of gamma rays emitted and absorbed without recoil, were assumed to be the same for the various phases present in the samples and for the different Fe species present in the same phase (Reference Gütlich, Bill and TrautweinGütlich et al., 2011; Reference MössbauerMössbauer, 1958; Reference TzaraTzara, 1961).

All quadrupole doublets observed corresponded to high-spin octahedral Fe paramagnetic species (further referred to as ‘para-Fe’) that were interpreted in most cases as clay structural Fe (Festr) in the present study. All magnetic sextets represent magnetically ordered species (also in octahedral coordination) interpreted as Fe in accessory minerals (Feacc). Depending on the sample type, up to three different spectra were collected. In the case of purified clay samples, which showed only a paramagnetic quadrupole doublet corresponding to structural Fe, Mössbauer spectra at 300 K were collected, using a low-velocity range (± 4 mm s–1) which displays a higher resolution, particularly on the quadrupole components. In the case of a clay sample (GeM), the presence of Fe (oxyhydr)oxide impurities required the systematic collection of spectra at lower temperature and at a higher velocity range (77 K, ± 12 mm s–1) to improve the sensitivity toward magnetic impurities. In this case, room temperature data at a high velocity range were also collected to confirm the 77 K data. In the absence of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides, room temperature data at lower velocity range were further collected to improve the resolution of data. In the case of pure Fe (oxyhydr)oxide samples, more resolved data at both temperatures were collected to discern better possible finer structural modifications. In addition, some components exhibited broadened and asymmetrical lines, due to either a lack of crystallinity or the presence of nanograins giving rise to superparamagnetic relaxation phenomena: these components were described by continuous distribution of quadrupole splitting or hyperfine field. Only the mean refined values of the hyperfine parameters (noted as < >) are reported in corresponding tables. The hyperfine structures are complex and reveal the presence of different Fe species: the consistency of the Mössbauer data based on the good correspondence found in the overall extent of Fe reduction between the various spectra collected on the same sample at various temperatures was preferred to the characteristic goodness of fit quality, which provided a mathematical rather than a physical criterion. All spectra and hyperfine parameters are presented in the Supporting Information (Figs. S5–S22 and Tables S6–S17).

Results and Discussion

Blank Experiments

A series of blank experiments was performed to assess first the behavior of the sulfide solutions in the absence of solid samples under the experimental conditions studied (Table 1). A small drop in sulfide concentration could be measured after a few hours of reaction, but remained limited (< 1 mM) even after > 1 month of stirring. It was accompanied by a pH increase in the lower pH experiment (from pH 9.0 to pH 10.4) and a noticeable color change of the red silicone rubber seal contained in the cap of the experiment tube. The surface of the portion of the seal exposed to the solution turned black (Fig. S3). Such a reaction of the seal was also observed in most experiments initiated at low pH (< 9), generally after an extended reaction time (24 h to several weeks depending on the experiment). Pieces of pristine seal were analyzed by Mössbauer spectrometry and found to contain hematite (Fig. S4). Similarly dramatic color changes were also observed on the surface of the reacted hematite powder. The hematite used as a pigment in the silicone rubber seal was in fact altered by the sulfide solution. However, this reaction did not seem to have any impact on the seal properties, even after extended reaction times.

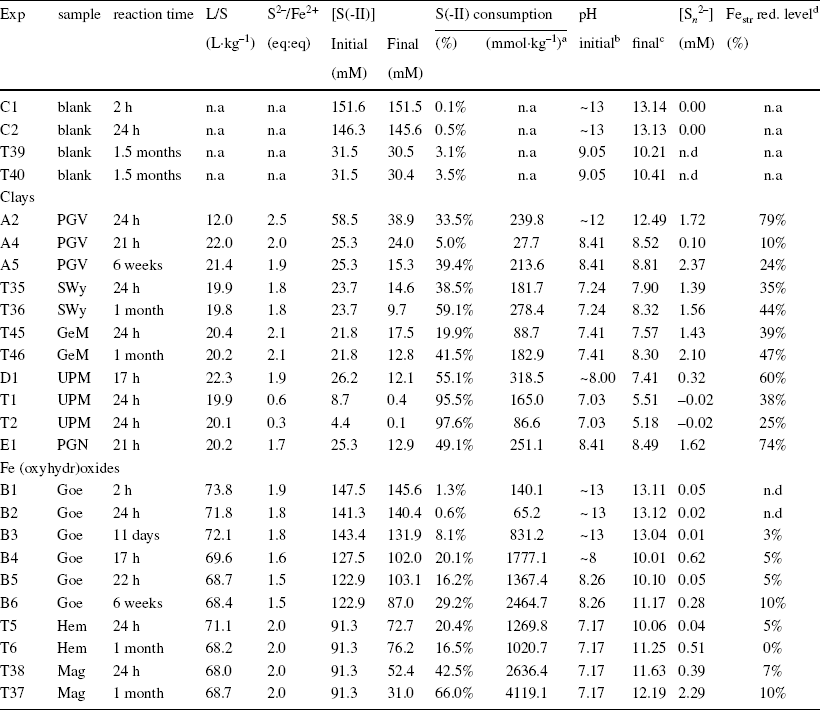

Table 1 Initial and final parameters of the batch experiments with pure clays and Fe (oxyhydr)oxides

n.d. = not determined; n.a. = not applicable

aconsumption in mmol of sulfide per kg of sample

binitial pH of stock solution

cfinal pH of supernatant

dreduction level of Fe (in clay) or quantities of Fe-sulfide determined from Mössbauer spectrometry.

Pure Clay Experiments

In contrast to the blanks, the experiments with the clays resulted in a substantial decrease in sulfide concentration (20–97%, Table 1), associated with a variable reduction of Festr (20–60%, Table 1, discounting the initial pristine reduction level, Table S3) and notable production of polysulfide (0.1–2.7 mM, Table 1). The reduction of structural Fe was also accompanied by a dramatic color change in the samples (from beige/white to dark green/blue, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Pristine and reacted dried samples of montmorillonite and goethite

Decreasing the pH of the reacting solution from 12 to 8 led to a drop in Festr reducibility in PGV, by more than three times (79% reduction at pH 12.5, vs 25% at pH 8.4, Table 1). Similar to PGV, the other two ‘Chambers’ montmorillonites, SWy and GeM, showed limited reducibility under the same conditions (~20–36% of Fe being reducible at pH 8.3, Table 1). In comparison, the Wyoming types, PGN and UPM, showed greater reactivity at similar pH (pH 8.4), with 2–3 times more reducible Festr (57–63%), although these samples were reacted for shorter times (< 24 h) than the Chambers-types (several weeks). The reactivity of Wyoming-type montmorillonites may thus be even greater with longer reaction times. Wyoming-type montmorillonites may also exhibit complete Festr reduction at higher pH. The greater reducibility of Wyoming-type montmorillonites compared to Chambers-types can be attributed to the fact that their structure displays smaller distortions (Reference Amonette and FitchAmonette, 2002; Reference Drits and ManceauDrits & Manceau, 2000; Reference Hadi, Tournassat, Ignatiadis, Greneche and CharletHadi et al., 2013). Indeed, the octahedral Mg2+ content of Chambers montmorillonites was significantly greater than that of Wyoming ones (at the expense of Al3+) which induced an initially greater octahedral charge (Table S3). The reduction of Festr led to a further increase in the octahedral layer charge (Reference Hadi, Tournassat, Ignatiadis, Greneche and CharletHadi et al., 2013), which increased further the layer distortions. Thus, the smaller the initial layer distortion, the greater the reducibility. Overall, only a portion of Festr was found to be reactive toward sulfur which implied that the initial excess sulfide regarding the share of active Fe was in fact notably greater (from 3 to 10, Table 2) than initially planned (~2, Table 1). No influences were observed on the initial cationic population (either Ca or Na dominant, Table S3), as Ca-UPM and Na-PGN were the most reducible, while Ca-SWy and Na-GeM were among the least reducible. However, the Ca-clay was found to be Na-exchanged during the experiments (in solutions of 100–250 mM Na).

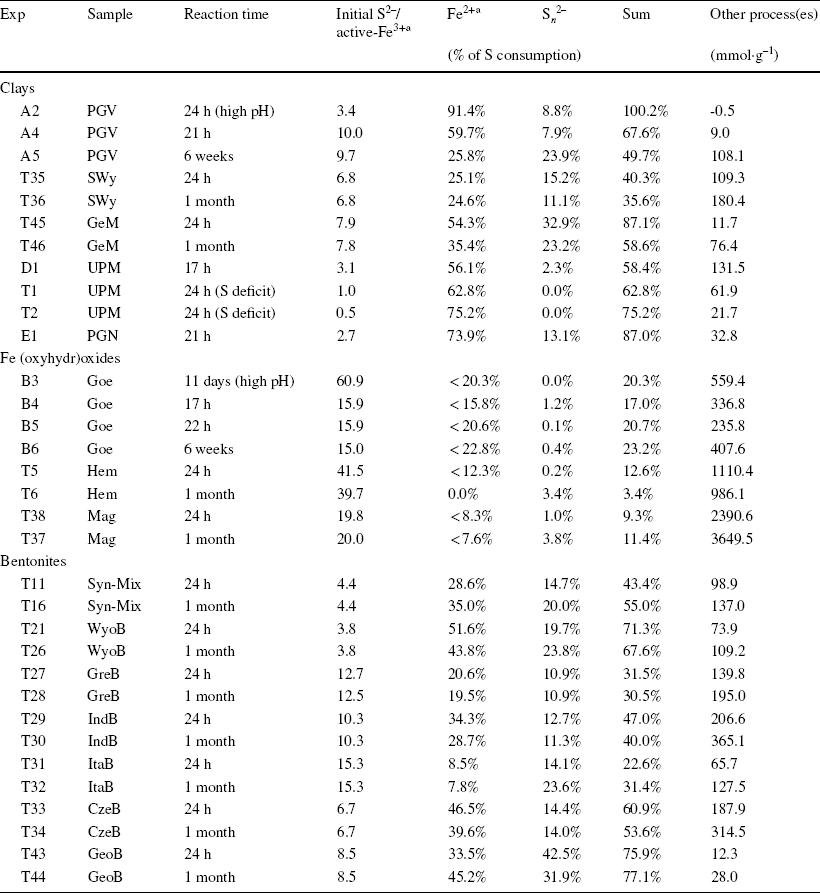

Table 2 Portion of sulfide consumption used for the reduction of Fe and the production of polysulfide, and sulfide oxidation capacity of the solid sample

aInferred from extent of Fe alteration determined by Mössbauer spectrometry. Calculation formulae are detailed in the Supporting Information

The production of polysulfide observed in all experiments with excess sulfide regarding Fe (0.1 to 2.7 mM, Table 1) indicated that, according to Eq. 3, elemental sulfur was a product of the sulfide oxidation by the clay Festr. The reaction of UPM with a deficiency of sulfide (relative to total Festr content, experiments T1 and T2, Table 1) resulted in an almost complete (95–98%) consumption of sulfide, no production of polysulfide, and a decrease in pH from 7 to 5. The pH drop was interpreted as stemming from depletion of sulfide and loss of its basic buffering capacity to the benefit of background HCl. The low pH, together with the deficit of sulfide explained the absence of polysulfide. Insoluble white elemental sulfur precipitates were observed on the walls of the experimental tubes. In the other experiments using excess sulfide, no coatings were observed on the walls of the tubes. The pH remained in a narrow range. It increased generally toward 8.5 in all experiments with excess sulfide, except for UPM where the pH instead decreased slightly to 7.4.

No significant alteration was observed in the Fe (oxyhydr)oxides fraction contained in the GeM sample (representing 7–9% of total Fe, Table S7).

Mass balance calculations of the share of sulfide consumption employed for Fe(III)str reduction (Eqs. 1 and 2) and polysulfide production (Eq. 3) showed that, at pH < 8.5, a notable portion (10–65%) of the measured sulfide consumption (based on concentration drop, Table 1) was due to other processes (up to 200 mmol kg–1, cf. other process(es) in Table 2). This portion also increased with extended reaction time. The experiment with PGV at high pH (> 12) was the only experiment without extra consumption of sulfide. The series of experiments at variable S:Fe ratio using UPM (D1, T1, and T2, Table 1) showed that the side sulfide consumption process(es) also occurred in the presence of deficit sulfide (with respect to redox-active Fe3+ sites), and became more important when the initial quantity of sulfide was increased. The overall extent of sulfide consumption was thus proportional to the initial sulfide concentration (at constant solid content, see UPM data in Table 2). Such additional consumption of sulfide indicated that other process(es) must occur, in parallel to Festr reduction and polysulfide production.

Fe (oxyhydr)oxide Experiments

The results obtained with the three Fe (oxyhydr)oxides were very different from those obtained with the clays. Although notable sulfide consumption was observed (up to 66%, Table 1), the production of polysulfide was generally much more limited (0.01–0.62 mM, with one exception, compared to 0.1–2.7 mM, Table 1) and only very moderate alteration of the solid was detected (Fe reduced by ≤ 10% compared to 10–80%; Table 1). Visually, the reacted Fe (oxyhydr)oxides exhibited a strong color change, from orange/red/brown to black (Fig. 1), similar to that observed with the silicon seal. Nevertheless, Mössbauer spectrometry revealed only limited changes (Table S9). The extent of Fe alteration did not exceed 17% of the total Fe (maghemite reacted for 1 month, Table S9), and the remaining (oxyhydr)oxide substrate appeared generally to be barely affected. The relative reactivity of the Fe (oxyhydr)oxides studied was in the order hematite < goethite < maghemite.

A first series of experiments conducted at high pH (> 13) with goethite (experiments B1 to B3, Table 1) showed a very limited interaction with sulfide. Small changes were detected only after several days of reaction (solid color change, 8% sulfide consumption, 3% alteration of Fe, Table 1). This slow reaction time at high pH was interpreted to be due to competitive sorption (Reference PoultonPoulton, 2003; Reference Poulton, Krom and RaiswellPoulton et al., 2004) on the solid surface (and possible subsequent reaction) between sulfide and other anions (Cl– and OH–). Solid alteration was substantially more pronounced at lower initial pH (experiment B4 to B6). In all cases, the pH increased rapidly to values > 10 within the first 24 h of reaction.

The same reaction product was observed in the three samples, but could not be identified unambiguously (Table S9). The hyperfine parameters indicated a planar Fe3+–S species (i.e. no apparent Fe reduction), rather consistent with a series of Fe(III)–S clusters found in proteins (Reference Pandelia, Lanz, Booker and KrebsPandelia et al., 2015) which have been proposed to adopt either cubic (Reference Kent, Huynh and MünckKent et al., 1980) or linear structures (Reference Kennedy, Kent, Emptage, Merkle, Beinert and MünckKennedy et al., 1984; Reference Muenck, Debrunner, Tsibris and GunsalusMuenck et al., 1972). The presence of such protein clusters can be ruled out in the present experiments; however, the occurrence of linear Fe3+–S n –S2– chains on the surface of the solid substrate could be envisaged. The quadrupole structure results typically from the presence of either quadrupole doublet(s) due to Fe-containing paramagnetic phase(s) and/or a quadrupole component due to Fe-containing superparamagnetic clusters or nanograins. In the present case, the quadrupole components observed at 300 K and 77 K would correspond to a surface coating of, at most, a few atomic layers.

The release of Fe2+ into solution (due to dissolution) cannot be ruled out completely, but it appears to be limited, given the virtually unchanged speciation and grain size of the substrate (according to the Mössbauer hyperfine parameters of the reacted solids, Table S9) and the limited or absent loss of mass from the solid sample (4, 5, and 7% mass loss for hematite, maghemite, and goethite, respectively, after 1 month of reaction).

The results of the entire series of experiments with Fe (oxyhydr)oxides point to a passivation reaction, where the morphology of the samples would be barely affected, but their surface would be entirely covered by a layer of an, as yet, unidentified Fe–S-bearing compound. Such a result appears to be an effect of the combination of an initial excess of sulfide (Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015; Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017) and the rapid increase in pH (Reference PoultonPoulton, 2003; Reference Poulton, Krom and RaiswellPoulton et al., 2004). The strong influence of the initial sulfide:iron ratio has already been reported and modeled in recent experiments on the synthesis of pyrite from a series of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides (goethite, lepidocrocite, and ferrihydrite), using an excess sulfide concentration relative to the available surface sites (Reference Hellige, Pollok, Larese-Casanova, Behrends and PeifferHellige et al., 2012; Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015; Reference Wan, Shchukarev, Lohmayer, Planer-Friedrich and PeifferWan et al., 2014) or to the total Fe present in the solid (Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017). An initial excess of sulfide over Fe led to the rapid precipitation of an FeS x species on the surface of the oxides, identified as “mackinawite with excess S” (Fe(II)S1+x by Reference Schröder, Wan, Butler, Tait, Peiffer and McCammonSchröder et al. (2020)) which in turn limited the release of Fe2+ to solution and, thus, decreased significantly the rate of pyrite formation (Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015; Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017). In these previously reported experiments (Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017), some pyrite (10–15%) was formed from the goethite after 4–6 months of interaction. Most of the goethite (80%) had already been altered to FeS x after 9 days of reaction. In the present experiments, only 10% of the goethite was transformed to a different FeS x species after 1.5 months of reaction time (experiment B6). The major difference in the present experiments was that the pH was not regularly re-adjusted to 7 as in the case of (Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017), but was allowed to drift with the reaction. Thus, it appears that along with the sulfide excess, a high pH (> 10 after a few hours of reaction only, cf. final pH in Table 1) further decreased the rate of alteration to pyrite by several orders of magnitude. Thus, one cannot rule out the possibility that the Fe-sulfide interaction was still in progress in the present experiments, but at such a slow rate that it would take several months to several years of interaction to discern further advancement.

The reaction was slightly more pronounced with maghemite compared to hematite and goethite, and another alteration was detected in addition to the unidentified common reaction product. In fact, the hyperfine structure revealed the presence of magnetic components that possess greater values of isomer shift, i.e. a progressive change from Fe3+ to Fe2+ species (7% of Fe, Table S9). It can be concluded that there was a slight alteration of maghemite to magnetite, which was detected after 1 month of reaction. The reaction with hematite was the most limited. A solid alteration product could be detected visually after 24 h of reaction (5% of total Fe, Table 1), but not after 1 month of reaction. The black, reacted solid turned red again after this extended reaction time. The concentration of sulfide also increased slightly from that of the first 24 h. This loss of solid reaction product with a concomitant increase in sulfide concentration was interpreted to be due to the detachment of the newly formed product from the hematite substrate followed by its dissolution (similar to that observed with lepidocrocite (Reference Hellige, Pollok, Larese-Casanova, Behrends and PeifferHellige et al., 2012)). It would then no longer re-form due to the increase in pH.

This limited reactivity observed with pure Fe(III) oxides explains why no alteration could be detected in the accessory Fe (oxyhydr)oxides contained in the GeM sample by Mössbauer spectrometry. Slight alteration may have occurred, but was probably below detection limits (2% of total Fe) and hidden by the larger central paramagnetic doublet attributed to clay Festr (Fig. S8).

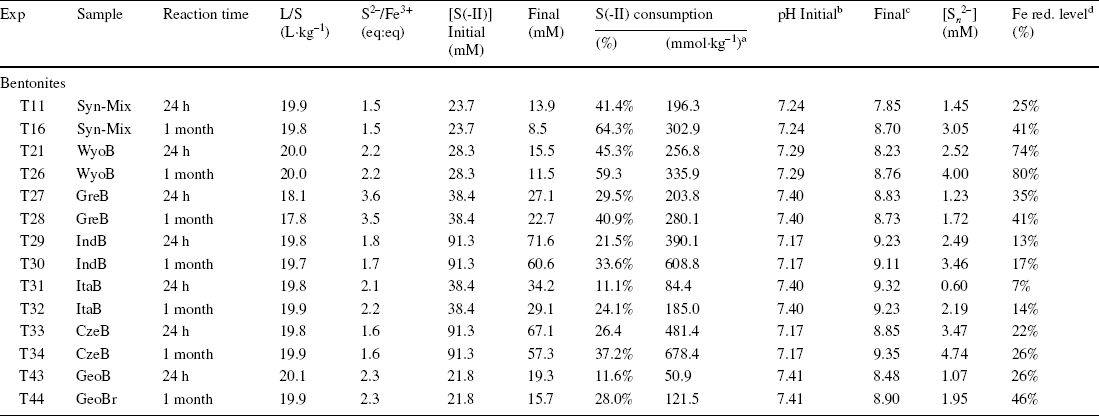

Bentonite Experiments

All the batch experiments with natural bentonites and the synthetic mixture (Table 3) showed similar results to the experiments with purified montmorillonites (Table 1), with an important consumption of sulfides (up to 65%, Table 3) related to the production of polysulfide (0.8–4.7 mM, Table 3), a slight increase in pH (from < 7.4 to > 8.5, Table 3), and similar dramatic color changes of the solid samples associated with variable reduction of Festr (14–60%, Table 3, taking account of the initial reduction level of the pristine sample, Table S4). The increase in pH was most pronounced with the bentonites rich in Fe (oxyhydr)oxides (ItaB, IndB, and CzeB), maybe due to some interaction between sulfide and goethite and hematite. Experiments using pure Fe (oxyhydr)oxides resulted in a stronger pH increase (from pH < 8 to pH > 10, Table 3). pH variations were probably more limited with bentonites, because of buffering by calcite and clay. Similar to experiments with pure clay and (oxyhydr)oxides, a notable share of the sulfide consumption was due to process(es) other than Festr reduction and S n 2– production (30–360 mmol kg–1, Table 2).

Table 3 Initial and final parameters of the batch experiments with bentonites

n.d. = not determined; n.a. = not applicable

aconsumption in mmol of sulfide per kg of sample

binitial pH of stock solution

cfinal pH of supernatant

dglobal reduction level of Fe, determined from Mössbauer spectrometry

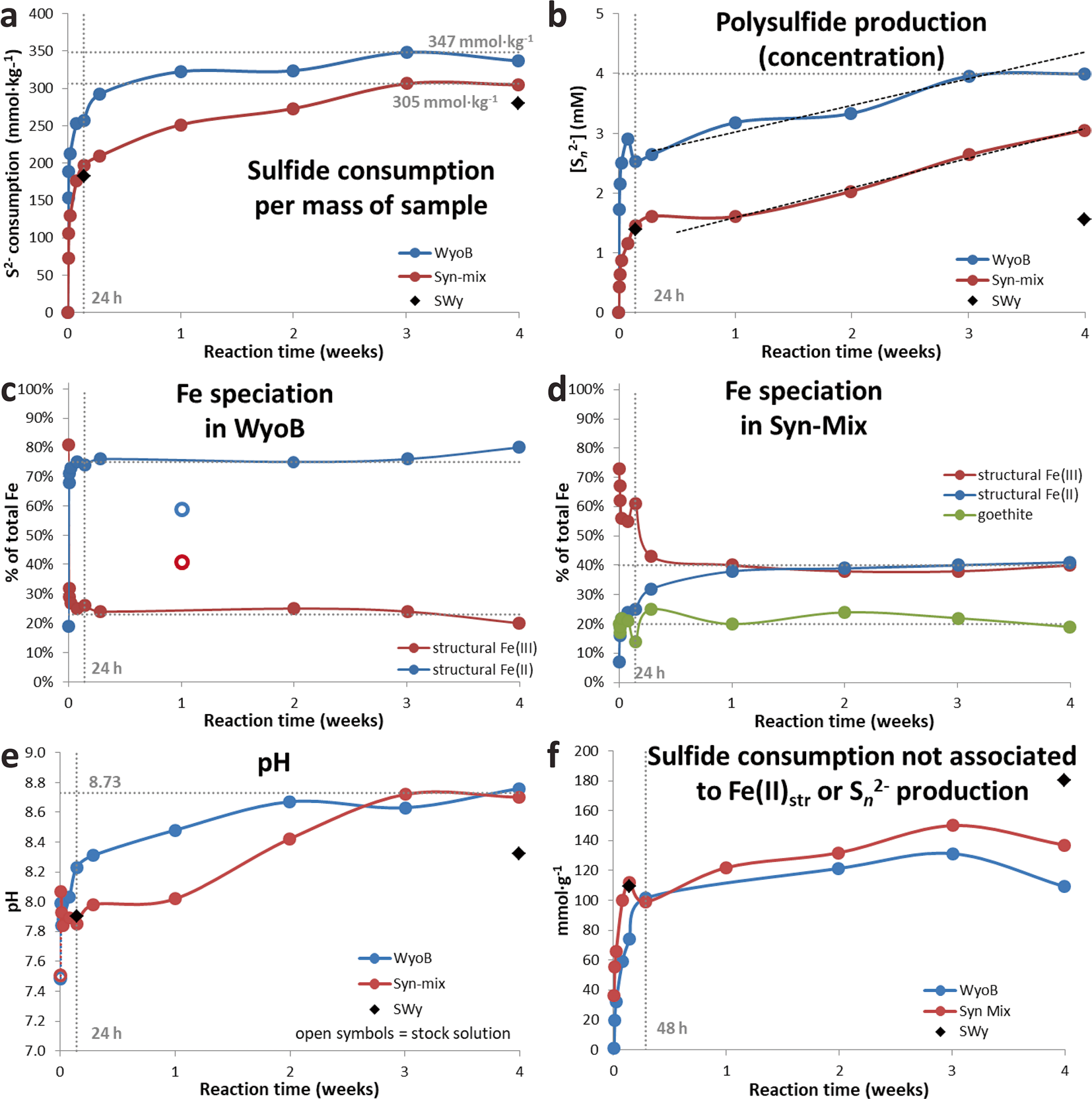

More time-resolved data were collected with WyoB (Wyoming-type) and Syn-Mix (Chambers-type). The evolution of the sulfide consumption as a function of time (Fig. 2a) indicated a fast consumption rate within the first 24 h, followed by a slower rate. A similar evolution was observed for the reduction of Festr (Fig. 2c, d, Table 3). While most (> 90%) Festr reduction was achieved within 48 h in WyoB, and within a week in the Syn-mix, other measured parameters (pH, polysulfide concentration, and sulfide consumption due to additional processes) showed more changes between 1 week and 1 month. Data collected after 1 month of interaction can, thus, be deemed representative of the maximum extent of reduction of Festr. Still, it cannot be ruled out that other side processes were still on-going. The continuous S n 2− production can be attributed to the progressive pH increase (which favors shorter-chain polysulfide and hence additional sulfide consumption). The process(es) behind the additional sulfide consumption seemed also to be pH-dependent (mitigated at high pH, cf. experiment A2, Table 2). The pH drift observed in all experiments may be due to slow mineral dissolution. The iron (oxyhydr)oxide-rich samples (ItaB, IndB, and CzeB) generally showed quicker and greater pH increases (> pH 9, Table 3), which can be attributed, in part, to interaction between sulfide and goethite/hematite (cf. previous section).

Fig. 2 Data from time experiments with Wyoming and Syn-mix showing the evolution of a sulfide consumption, b polysulfide concentration, c and d speciation of Fe in the solid sample, e pH, and f the supplementary sulfide consumption not associated with reduction of Festr or production of polysulfide

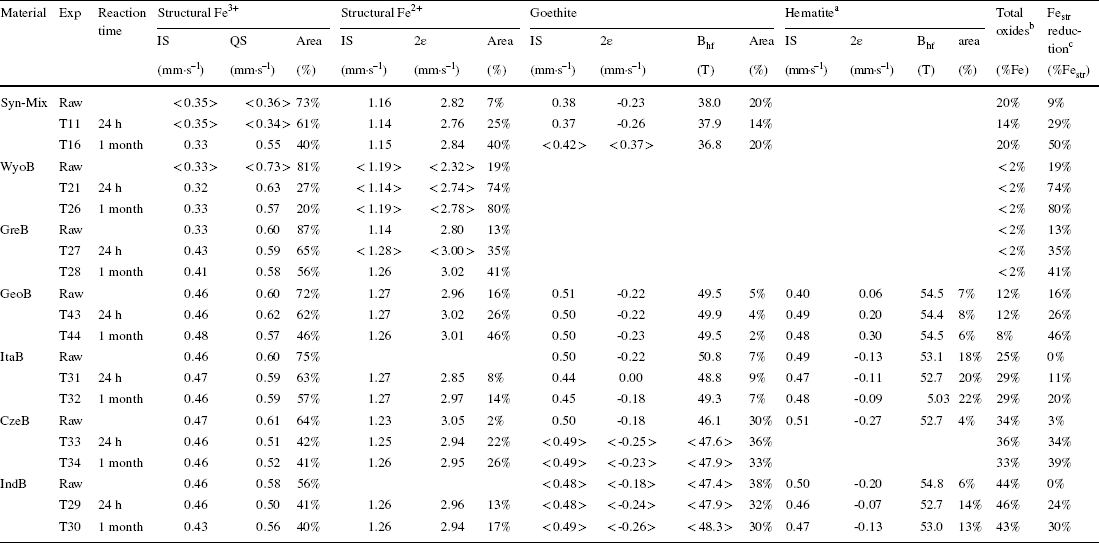

In contrast, the Fe (oxyhydr)oxide pool appeared largely unaffected in any of the samples investigated (Table 4) over the whole course of the experiments, despite dramatic color changes. The limited variations (<± 5%) in relative distribution of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides (total content and goethite:hematite ratio, Table 4) observed as a function of time is within the uncertainty of Mössbauer spectrometry and material homogeneity. The expected FeS x reaction product (< 3% of total Fe in sample) was too small to be detected in this case. The results indicated that Fe (oxyhydr)oxide alteration in the presence of high sulfide levels is also heavily mitigated in the presence of redox active clay minerals and at pH 9–9.5.

Table 4 Sum up of Mössbauer parameters collected on the series of experiments with bentonites (300 K data for the Syn-mix, GreB, and WyoB bentonites, and 77 K data for the other bentonites). Complete Mössbauer dataset can be found in the Supporting Information

aIn the case of GeoB, the reported hyperfine parameters and proportion actually account for species other than hematite, but which could not be identified unambiguously

bTotal (oxyhydr)oxide content (in % of total Fe)

cExtent of Festr reduction, i.e. Festr 2+/(Festr 2+ + Festr 3+)

Two main groups of bentonites can be distinguished, based both on their total Fe content (Table S2) and the type of their clay components. On one hand, the ‘low-Fe’ (< 7 wt.% Fe2O3) bentonites (WyoB, GreB, GeoB, and ItaB) contain mainly Festr located in a clay structure consistent with montmorillonites (< 0.55 mmolFe g–1, Table S4). Syn-Mix, composed mainly of the Chambers-type montmorillonite, SWy, can be associated with the ‘low Fe’ bentonite group also. On the other hand, the ‘high-Fe’ (> 16% Fe2O3) bentonites (IndB and CzeB) contain not only a larger proportion of Feacc (in fact equivalent to that of Festr) but the clay component of the bentonite appears to be richer in Fe also (1.2–1.4 mmolFe g–1) than for other reported montmorillonites (Reference Bergaya, Theng and LagalyBergaya et al., 2006; Reference Gates and KloproggeGates, 2005; Reference Grim and GüvenGrim & Güven, 1978; Reference Grim and KulbickiGrim & Kulbicki, 1961; Reference SchultzSchultz, 1969). These two bentonites are probably composed of a smectite which is richer in iron, i.e. a beidellite-type (Reference Gates and KloproggeGates, 2005; Reference Stucki, Golden and RothStucki et al., 1984).

Mössbauer data on reacted samples (Tables 3 and 4) enabled the further distinction of two sub-groups of ‘low-Fe’ bentonites. On one hand, WyoB stands out as the most reactive one, with nearly 60% of sulfide-reducible Festr (at pH between 7 and 9), as observed with Wyoming-type montmorillonites (UPM and PGV, Table 1). On the other hand, the other ‘low-Fe’ bentonites contain smaller amounts of sulfide-reducible Festr (20–40%), consistent with levels observed for Chambers-type montmorillonite (PGN, SWy, and GeM, Table 1). The clay component in GeoB and ItaB bentonites is probably of this type, according to their large Mg content (> 4 wt.% MgO, Table S2). GreB displays a smaller Mg content (< 2.5 wt.% MgO), which is more consistent with Wyoming-type montmorillonites. The structural formula of the clay component of GreB sample was not determined. Still, published data for samples of similar origin (Reference Karnland, Olsson and NilssonKarnland et al., 2006; Reference Kiviranta and KumpulainenKiviranta & Kumpulainen, 2011; Reference Kumpulainen and KivirantaKumpulainen & Kiviranta, 2010) allow a structural formula (0.55–0.75 Mg atoms/unit-cell) to be inferred at the border between Chambers- and Wyoming-type montmorillonites (according to the classification of Reference Grim and KulbickiGrim and Kulbicki (1961) and Reference SchultzSchultz (1969)). Despite the rather large Fe content, ItaB showed the smallest share of reducible Festr (14% of Festr, Table 3). The two Fe-richest bentonites (IndB and CzeB) also exhibited a relatively limited share of reducible Festr (30–36% of Festr, Table 3), similar to Chambers-type bentonite.

Clay–sulfide Redox Interaction in the Presence of Excess Sulfide

Clay Fe(III)str is located as isolated sites within the octahedral sheet of montmorillonites (Reference Gates and KloproggeGates, 2005; Reference Vantelon, Pelletier, Michot, Barrès and ThomasVantelon et al., 2001) and is considered generally to be the sole electron acceptor in the clay structure (Reference Stucki, Bergaya, Theng and LagalyStucki, 2006b). The probability of neighboring Festr sites is rather small. Moreover, depending on the redox conditions, only a fraction of the Festr site may be reactive, increasing the isolation of the reactive Fe sites (from each other). The reduction of Fe in such an Fe-poor structure occurs mainly by direct electron transfer from the reductant (Reference Latta, Neumann, Premaratne and SchererLatta et al., 2017; Reference Neumann, Sander and HofstetterNeumann et al., 2011; Reference Stucki, Bergaya, Theng and LagalyStucki, 2006a), rather than between neighboring Festr sites (as observed at the edges of nontronite sheets Reference Komadel, Madejovà and StuckiKomadel et al., 2006; Reference Neumann, Olson and SchererNeumann et al., 2013) or in (oxyhydr)oxides (Reference Handler, Frierdich, Johnson, Rosso, Beard, Wang, Latta, Neumann, Pasakarnis and PremaratneHandler et al., 2014; Reference Rosso, Yanina, Gorski, Larese-Casanova and SchererRosso et al., 2010; Reference Yanina and RossoYanina & Rosso, 2008)). The oxidation of sulfide to elemental sulfur (Eq. 2) can be described by a two-step reaction, in which a radical intermediate (sulfanyl) is produced (Reference Steudel and SteudelSteudel, 2003). The redox reaction with Festr, thus proceeds in two steps (Eqs. 4 and 5).

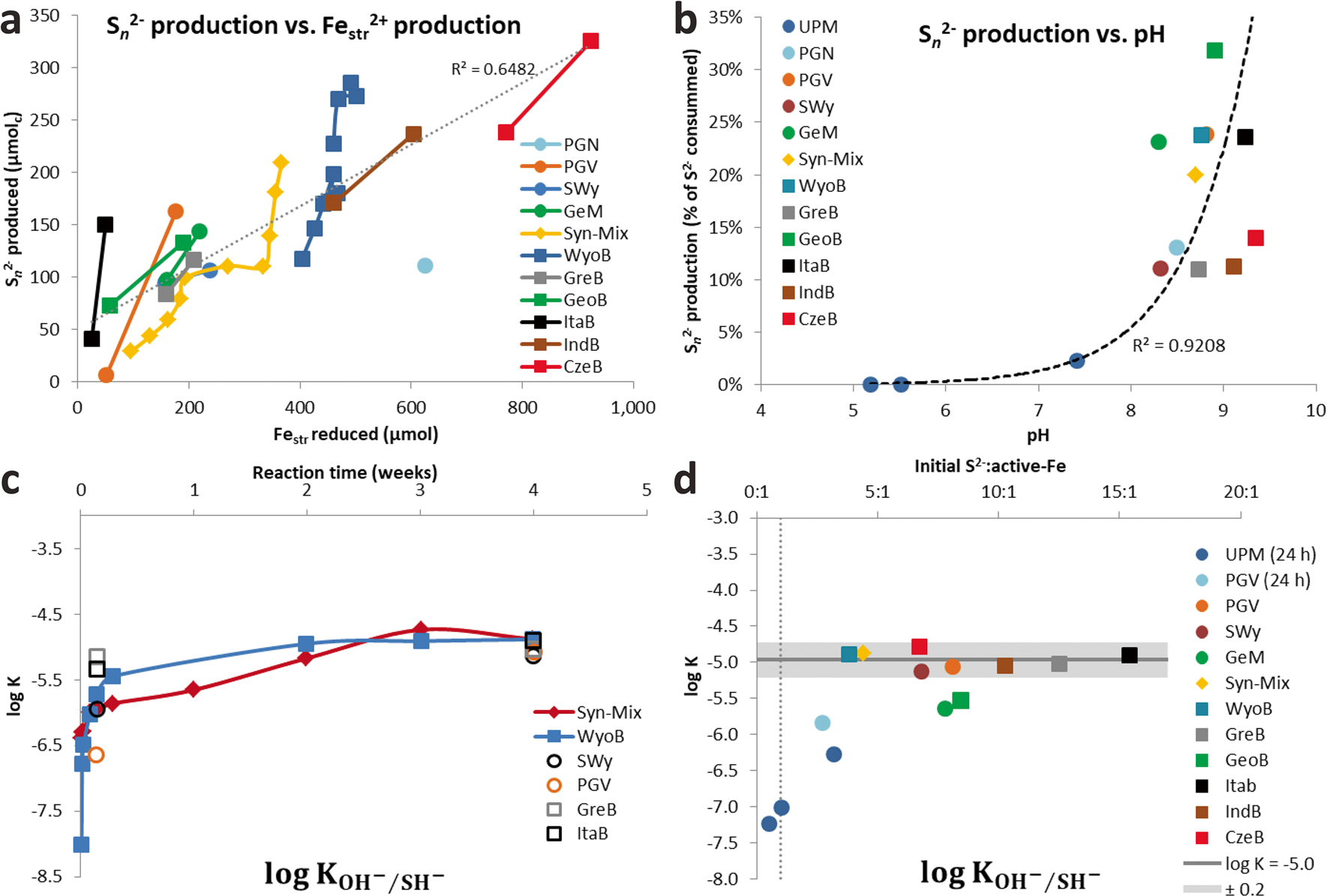

The elemental sulfur which is eventually formed by this reaction can react further with excess sulfide to form polysulfide (Eq. 3). This reaction is dependent on pH, both regarding its extent and the average chain length (n) of the polysulfide formed (Reference Steudel and SteudelSteudel, 2003; Reference Steudel and ChiversSteudel & Chivers, 2019). Higher pH favors a shorter chain length. Between pH 8 and 10, n varies between 6 and 3, respectively (Reference Steudel and SteudelSteudel, 2003), i.e. one sulfide anion can react with 3–6 elemental sulfur atoms. In most experiments, sulfide remained always in excess regarding elemental sulfur, and the pH (>8) was high enough to ensure complete recovery of sulfur formed as polysulfide. As a consequence, polysulfide production was proportional to the extent of Festr reduction in the solid (Fig. 3a). The share of sulfide (regarding the total pool of sulfide consumed after 1 month of interaction with bentonite) involved in the production of polysulfide was, in part, affected by the pH, but also varied between series of experiments at similar pH (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3 a Amount of polysulfide (S n 2–) produced as a function of the amount of reduced Festr; b share of sulfide consumption involved in S n 2– production as a function of the final pH of the supernatant; c evolution of log KSH/OH (cf. Eq. 10) as a function of time, and d log KSH/OH (cf. Eq. 10) as a function of the initial S2–: active-Fe ratio

The initial sulfide concentration was set to ensure a one-fold excess of sulfide relative to total Fe in the solid. However, because only a portion of this Fe turned out to be reactive toward sulfide, the excess sulfide regarding reactive Fe varied between 3- and 8-fold for the pure clays, and between 3- and 14-fold for the bentonites (Table 2). As the two sulfide oxidation steps (Eqs. 4 and 5) are competing reactions, the use of an excess sulfide concentration relative to active Fe sites can favor the production of sulfanyl radicals (Eq. 4), without subsequent surface oxidation to elemental sulfur (Eq. 5). Sulfanyl radicals are, however, considered to be much more reactive and short-lived species than sulfide anions (Reference Steudel and SteudelSteudel, 2003). The radicals generated can react further with elemental sulfur (generated by complete oxidation) to form polysulfanyl, in the same way that sulfide anions form polysulfide (Eq. 3). Moreover, sulfanyl radicals and polysulfanyl can undergo similar mechanisms of recombination into more stable polysulfide (e.g. Eqs. 6–8).

Such recombination mechanisms re-generating polysulfide (and thus equivalent amounts of sulfide and elemental sulfur, following Eq. 3) result in no net overconsumption of sulfide.

In all experiments, Festr reduction and subsequent polysulfide production could not account for all the measured consumption of sulfide. A portion of HS– could also be envisaged to exchange with structural OH groups (Eqs. 9 and 10).

Assuming this process was behind all the additional consumption of sulfide observed in all the experiments with pure clays (Table 2), an equilibrium constant can be derived for each reported experiments (Eq. 10), using data from Table 1 (L/S, final pH, final sulfide concentration) and Table 2 (the sulfide consumption due to other process(es) accounting for the final concentration in structural SH groups). The final concentration in structural OH– groups can be derived by subtracting the final concentration in structural SH groups (other process(es), Table 2) from the initial OH content (Table S4). For the bentonites, the initial amount of structural OH groups can be derived from the average pure montmorillonites content (5.34 mol kg–1) corrected by the smectite content in the bentonite (Table S4). Finally, regarding the Fe (oxyhydr)oxides-rich bentonites (CzeB, IndB, and ItaB), the share of sulfide consumption associated with interactions with goethite and hematite (derived from their respective contents, Table S4, and their respective total sulfide consumption, Table 1) can be deduced from the excess sulfide consumption. Following such calculations, very similar log K values were obtained in all the experiments. The values showed large variations in the first 24 h of reaction, and equilibrium was reached after just 3 weeks (Fig. 3c). Log K values for all 1-month experiments with pure clays and bentonites, with the exception of the Georgian clay (both raw GeoB and purified GeM), fell within a narrow range (–5.0 ± 0.2, Fig. 3d). This result tends to support the concept of clay sulfidation (Eq. 9) and would correspond to an exchange of 3–4% of the structural OH groups for HS groups after 1 month of reaction. The reason for the slightly greater resistance of the Georgian clay to sulfidation (Log K = –5.6, 1.4% exchange) is unknown. The sulfide excess over the active Festr had no influence on the log K values of 1-month experiments (Fig. 3d), which indicates that the role of radicals in the additional sulfide consumption can be ruled out. Contrary to sulfide oxidation by Festr (Eqs. 4 and 5), such an exchange reaction can be considered reversible, depending only on the pH and the sulfide concentration in solution.

Fe (oxyhydr)oxides–sulfide Redox Interaction in the Presence of Excess Sulfide

Reactions between sulfide and Fe (oxyhydr)oxides (goethite, hematite, magnetite, lepidocrocite, and hydrous ferrous oxides) have been studied for several decades (Reference Dos Santos Afonso and StummDos Santos Afonso & Stumm, 1992; Reference PoultonPoulton, 2003; Reference Poulton, Krom, Rijn and RaiswellPoulton et al., 2002, Reference Poulton, Krom and Raiswell2004; Reference Pyzik and SommerPyzik & Sommer, 1981; Reference RickardRickard, 1974). The reaction mechanisms have been proposed to proceed via a series of stepwise surface reactions (Eqs. 11–14), adapted from Reference Dos Santos Afonso and StummDos Santos Afonso & Stumm (1992) and Reference Poulton, Krom and RaiswellPoulton et al. (2004).

Dissolution, i.e. generation of new Fe3+ surface sites (4th step, Eq. 14) is conditioned by the release of the newly generated Fe2+. This release is pH-dependent and competes with at least two other possible reactions (Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015). As semiconductors, Fe (oxyhydr)oxides are prone to bulk conduction of electrons, which results in removal of Fe2+ surface sites and generation of bulk Fe2+ (Eq. 15) (Reference Hiemstra and van RiemsdijkHiemstra & van Riemsdijk, 2007). The subsequent fate of both new surface Fe3+ sites and bulk Fe2+ species depends on the host (oxyhydr)oxides structure. Lepidocrocite and ferrihydrite structures can accommodate small amounts of Fe2+, but this eventually promotes a recrystallization process of the host Fe3+ oxides (at the sorption site) toward a more stable species such as goethite and/or hematite, and even magnetite if the concentration in Fe2+ is sufficiently high (Reference Cornell and SchwertmannCornell & Schwertmann, 2003; Reference Hellige, Pollok, Larese-Casanova, Behrends and PeifferHellige et al., 2012; Reference Hiemstra and van RiemsdijkHiemstra & van Riemsdijk, 2007; Reference Jang, Mathur, Liermann, Ruebush and BrantleyJang et al., 2008; Reference Liu, Guo, Li and WeiLiu et al., 2009; Reference Pedersen, Postma, Jakobsen and LarsenPedersen et al., 2005; Reference Silvester, Charlet, Tournassat, Géhin, Grenèche and LigerSilvester et al., 2005; Reference Williams and SchererWilliams & Scherer, 2004). In the case of more stable oxides such as goethite and hematite, the Fe2+ incorporated is released eventually to the solution from another crystal surface, thus also promoting recrystallization (at sorption and release sites) but rather isostructural in this case (Reference Handler, Frierdich, Johnson, Rosso, Beard, Wang, Latta, Neumann, Pasakarnis and PremaratneHandler et al., 2014; Reference Rosso, Yanina, Gorski, Larese-Casanova and SchererRosso et al., 2010; Reference Yanina and RossoYanina & Rosso, 2008).

The release of Fe2+ from the surface (Eq. 14) was also proposed to compete with precipitation with sulfide “at the crystal rims” as a form of mackinawite (Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015) incorporating polysulfide and elemental sulfur (FeS x with x > 1) (Reference Schröder, Wan, Butler, Tait, Peiffer and McCammonSchröder et al., 2020; Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017). When aqueous sulfide is in excess with respect to Fe3+, the Fe2+ generated is “trapped” by aqueous S2– to precipitate as FeS x , and pyrite formation occurs eventually following slower dissolution of FeS x (Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017). Following Eqs. 11–14, reductive dissolution of Fe3+ by 1 mol of sulfide produces 2 mol of Fe2+ and one mole of S0. Thus, in theory, with a sufficient sulfide excess, 1 mol of FeS and 1 mol of FeS2 can be formed, or an equivalent two moles of FeS1.5 (i.e. 1 < × 1.5). At pH 7 in the presence of notable excess sulfide (Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017), complete conversion of lepidocrocite to FeS x occurred in < 3 days and nearly complete conversion of goethite in 9 days. Complete conversion of the (oxyhydr)oxides shows that FeS x precipitation does not necessarily compete with the generation of new surface sites and further reductive dissolution. In this case, FeS x appears to precipitate instantly at the expense of the (oxyhydr)oxide substrate.

In the present work, alteration of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides was much more limited (< 10% conversion to FeS x ) than in the study from Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al. (2017). This may be explained largely by the high pH, which was shown to decrease notably the rate of FeS x formation (Reference PoultonPoulton, 2003; Reference RickardRickard, 1974) Still, the FeS x species that was detected is different from the defect mackinawite observed by Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al. (2017). It is formed only of Fe3+. This accounts for rapid and complete electron transfer toward the bulk (Eq. 15). In the case of maghemite, partial conversion (7%) to magnetite was detected as a result of such Fe2+ generation at the crystal surface. In the case of hematite, the reaction product formed after 1 day eventually detached from the surface (as observed by Reference Hellige, Pollok, Larese-Casanova, Behrends and PeifferHellige et al. (2012) with lepidocrocite) and unaltered hematite was recovered after 1 month. This could be interpreted as an effect of recrystallization of the hematite surface (induced by Fe2+ generation at the surface, Reference Rosso, Yanina, Gorski, Larese-Casanova and SchererRosso et al. (2010)) to a more stable form, leading to detachment of the alteration product and preventing further alteration by sulfide. The production of polysulfide could also be envisioned to be linked with the inhibitory process and generation of such surface species. At a sufficient excess of sulfide regarding available Fe surface sites, polysulfide can even be expected to be generated following recombination of sulfanyl (Eqs. 7 and 8), as long as HS• radicals are generated in sufficient quantities. Short-chain polysulfide S2 2– can, thus, theoretically, be generated prior to the release of the first generation of surface Fe2+ and such species can also interfere with the early steps of the sulfide-Fe (oxyhydr)oxide interaction process described by Eqs. 11–14 (Eqs. 16–17).

Such surface-bound species would be further at equilibrium with the oxide substrate following instant electron transfer (Eq. 15) toward the bulk (Eq. 18).

Provided that initial sulfide saturation would be sufficient, such a reaction would lead to a very rapid and homogeneous saturation of surface sites by a ferric sulfur species. This could explain the rapid inhibition of the interaction. The inhibition could also be helped by the presence of a thin but stable magnetite interface between the oxides substrate and the newly formed surface species (Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015) and the increased pH. The majority (> 80%) of the sulfide consumption measured in these experiments remains unexplained (cf. other process(es), Table 2). The expected side reactions of sulfide precipitation (as FeS mackinawite or FeS2 pyrite) associated with Fe reduction were also very limited (not detected on solids, and no colloids visible in solutions) and, therefore, cannot account for the excessive sulfide consumption.

Determination of Sulfide Oxidation Capacity (SOxC)

The SOxC discussed below corresponds to the quantity of sulfide oxidized by Fe(III) present in the clay mineral (Eqs. 4–5) and oxyhydr(oxides) (Eqs. 11–14). The greater extents of sulfide consumption per sample mass (Table 1) depend on the initially added sulfide concentration (as well as solid sample properties), and account for additional side process(es) of polysulfide production (due to the excess sulfide, Eq. 3), possibly reversible clay sulfidation (as proposed in Eq. 9), and other unidentified reaction(s) with iron (oxyhydr)oxides. Mössbauer data can be used to determine the extent of sulfide consumption resulting from oxidation by iron contained in the solid samples (Table 5). In the case of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides, this value represents a smaller estimate as it is based on the total extent of Fe alteration and the assumption that Fe2+ was produced exclusively. Some of the alteration may be due to the recrystallization of the substrate (with no net redox change) induced by Fe2+ produced by Fe surface reduction (Reference Cornell and SchwertmannCornell & Schwertmann, 2003; Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015; Reference Silvester, Charlet, Tournassat, Géhin, Grenèche and LigerSilvester et al., 2005). This was observed in the case of the maghemite reacted for 1 month, which also partly (7%) transformed to magnetite. Moreover, the Mössbauer hyperfine parameters are more consistent with an Fe3+-rich product (Table S9 and Fig. S12). Although the SOxC determined for Fe (oxyhydr)oxides does not include the portion of sulfide which can be involved potentially in the side precipitation process (Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015), the values appear to be relatively small compared to the large Fe3+ content in the materials studied (> 10,000 mmol Fe kg−1). The use of a large excess of sulfide over the available Fe surface sites probably led to a passivation effect which has not been reported previously. The precipitate on the oxide surface could not be identified unambiguously.

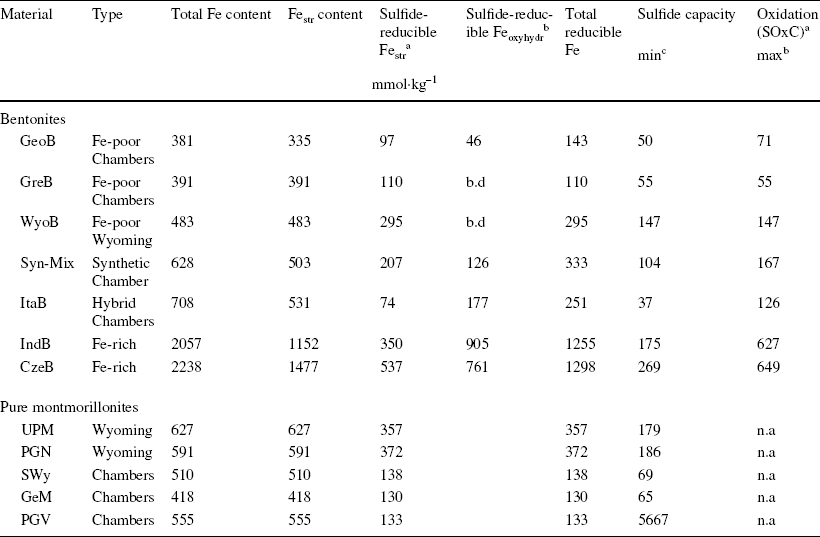

Table 5 Fraction of sulfide-reducible Fe species in the studied sample and corresponding sulfide oxidation capacity (SOxC) of the material (n.a.: not applicable)

aAt pH ~8.5–9.5

bAssuming all Fe in (oxyhydr)oxides would be 100% reducible by sulfide

cAssuming only Festr would be reducible by sulfide

Conversely, the reaction between sulfide and structural iron in pure smectite minerals was limited mainly by the amount of available sulfide (an excess was necessary to achieve maximum reduction) and the reaction time (at least 48 h to 1 week was necessary to achieve maximum reduction). The extent of the reaction was also controlled by the pH and clay structure. Despite similar total Fe contents (Table S3), the Wyoming-type montmorillonite (UPM, PGN) showed greater redox reactivity than the Chambers-types (GeM, PGV, and SWy), reacting more quickly and achieving a ~3 × greater sulfide oxidation capacity at pH ~8.

Mössbauer data for bentonite samples reacted for 1 month at pH 8–10 allowed the derivation of the amount of sulfide-reducible Festr in the sample (Table 5), and thus the corresponding SOxC of the clay component only. An upper estimate of the bentonite SOxC can, however, be derived by assuming that, in addition to clay Festr, 100% of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides would be reducible under lower sulfide fluxes (following models from Reference Dos Santos Afonso and StummDos Santos Afonso & Stumm (1992) and Reference Poulton, Krom and RaiswellPoulton et al. (2004), Eqs. 10–13).

The SOxC of a given bentonite is conditioned significantly by the nature of the clayey component. The low Fe-bearing GeoB and GreB stand out as the bentonites containing the least SOxC. Despite a similar Fe content, the WyoB shows a 3 × greater SOxC. This difference correlates well with what was observed between pure Wyoming- and Chambers-type montmorillonites. In turn, a smaller SOxC was determined for ItaB, despite its slightly larger Fe content. In that case, the global SOxC may be underestimated due to inhibition of the interaction between sulfide and Feacc under the applied experimental conditions. The results are, nevertheless, consistent with Chambers-type bentonites.

As expected, the two Fe-richest bentonites (IndB and CzeB) showed the largest SOxC values. This capacity appears not to be directly proportional to the Fe content, however. As for ItaB, the actual global SOxC may be underestimated due to the inhibition of the interaction between sulfide and the notably larger Feacc content. Still, the clay component itself also appears to be less sensitive to reduction by sulfide, in comparison with the ‘low-Fe’ bentonites. The SOxC of the clay component of IndB and CzeB is of the same order as that of Wyoming type, despite their ~3–4 × greater Festr content. Such differences in Festr reactivity can also be expected, because of their notably greater Festr content, indicative of beidellite-type clay. A broader distribution of Festr redox potential (and smaller relative reducibility) can be expected from such a structure. Indeed, a big contrast in redox potentials was determined for Festr in the Chambers-type SWy-2 and in a series of Fe-rich nontronites (Reference Gorski, Aeschbacher, Soltermann, Voegelin, Baeyens, Marques Fernandes, Hofstetter and SanderGorski et al., 2012a, Reference Gorski, Klüpfel, Voegelin, Sander and Hofstetterb). A similar contrast in redox reactivity could be derived from experiments of dithionite reduction of the Wyoming-type UPM and two Fe-richer beidellites (Reference Stucki, Golden and RothStucki et al., 1984).

Implications for the Bentonite Buffer in the Repository

The relevance of the notable contrast in SOxC observed between the three bentonite groups (Chambers, Wyoming, and Fe-rich) in the context of an underground repository is conditioned by two main aspects. On the one hand, the estimated SOxC determinations probably underestimate the contribution of the (oxyhydr)oxides pool to the global sulfide oxidation by the bentonite, which may be more important in situ where less sulfide flux (and thus no inhibition of iron oxide reduction) should be expected. On the other hand, the global extent of sulfide–bentonite interaction in compacted bentonites might be less pronounced than in the present experiments employing suspensions. Thus, the SOxC of compacted bentonites remains to be determined, although relative differences observed in batch experiments may translate into compacted conditions.

Another important aspect is the impact of Festr reduction on the clay structure, and thus on its swelling properties. Festr reduction leads to an increase in the layer charge, which is partly compensated by the increase of the CEC and dehydroxylation of the octahedral sheet (Reference Drits and ManceauDrits & Manceau, 2000; Reference Hadi, Tournassat, Ignatiadis, Greneche and CharletHadi et al., 2013; Reference Lear and StuckiLear & Stucki, 1985; Reference Stucki, Golden and RothStucki et al., 1984). Partial replacement of structural OH groups by SH groups can also be envisioned (as proposed in Eq. 9). Festr reduction thus further impacts other interconnected properties of the clay (e.g. swelling capacity, hydration, pH) (Reference Stucki, Bergaya, Theng and LagalyStucki, 2006a), in addition to converting the clay to being more reductive toward other potential solutes (clay Festr can, thus, act as an electron buffer). The impact of Festr reduction on bentonite performance as a sealing material still remains to be evaluated. It thus remains unclear whether extended Festr reduction could be beneficial, detrimental, or have no notable impact on the bentonite’s performance.

Ranking the three groups of bentonites based on their SOxC alone is not straightforward. The Fe-richest bentonites (Cze and IndB) have the largest SOxC values. However, an extended interaction with sulfide should lead to both an important reductive dissolution of (oxyhydr)oxides associated with partial re-precipitation as iron sulfide, and resulting in changes in density and porosity, in addition to notable clay Festr reduction with (still) unanticipated impact on bentonite properties. Wyoming-type bentonites are poorer in potentially reactive Feacc, but still display large SOxC values associated with their clay component. These bentonites would, thus, be much less prone to reductive dissolution, but still have a highly reactive Fe component. Finally, Chambers-type bentonites are the bentonites with the smallest SOxC (and generally display smaller amounts in Feacc). In the case that Festr reduction (and the other associated structural changes) could be detrimental to the swelling properties, this lesser reducibility of Festr in Chambers-type bentonite could in fact turn out to be an advantage, making them more resistant to alteration by sulfide.

Conclusions

The present work outlines how dioctahedral smectites, which are the main mineral components of bentonites, are major agents for sulfide oxidation. At pH 7–9 (25°C), only a certain share of Festr (20–60%) was reactive toward sulfide. This share depended on the clay-mineral structure. Chambers-type montmorillonites were 2–3 times less prone to sulfide oxidation than Wyoming-type montmorillonites or the more ferruginous types of smectite. The chemical conditions explored in the present study (high liquid/solid ratios and high sulfide concentrations) are not really representative of common environmental conditions. Nevertheless, the sulfide-to-iron ratio may not have a major influence on the maximum reduction extent of Festr because clay reduction can be envisioned as a cumulative process (Festr can be reduced progressively by incremental additions of deficit sulfide), depending mainly on the applied redox potential and the quantity of available electron donors (Reference Gorski, Klüpfel, Voegelin, Sander and HofstetterGorski et al., 2012b). In addition, clay compaction may further restrict possible clay–sulfide interaction. Such aspects remain to be investigated.

In parallel to redox interactions with Festr, another clay-specific process of sulfide consumption was observed. It is tentatively described as clay sulfidation through reversible exchange of structural OH for SH. The equilibrium constant for this reaction determined for the whole series of clay samples (excluding the less reactive Georgian ones GeoB and GeM) is relatively low (log K = -5.0 ± 0.2), which implies that high-sulfide concentrations (regarding solid) are necessary to achieve noticeable (> 5 mmol kg–1) exchange. As for the redox process with Festr, clay compaction (anionic exclusion) and lower sulfide fluxes may reduce the impact of such processes in environmental conditions.

With regards to Fe (oxyhydr)oxide, the sulfide/iron ratio (Reference Peiffer, Behrends, Hellige, Larese-Casanova, Wan and PollokPeiffer et al., 2015; Reference Wan, Schröder and PeifferWan et al., 2017), along with pH (Reference PoultonPoulton, 2003; Reference RickardRickard, 1974), were shown to have a significant influence on the possible alterations. Deficit of sulfide leads to rapid pyrite formation, while sulfide excess leads to the formation of metastable FeS x intermediates, which may eventually alter to pyrite. Increased pH slows down such a process by several orders of magnitude. The high pH (> 9) in the present experiments resulted in some sort of inhibition of the alteration process. On the other hand, the inhibition enabled formation of an as-yet not reported early intermediate in the alteration process leading to pyrite, as a surface-bound Fe3+ disulfide. Such intermediates may also be formed at lower pH and lower sulfide concentrations, but would be unstable and rapidly altered to more stable forms of iron sulfide. This result underlines that the sequence leading from Fe (oxyhydr)oxide to pyrite remains to be fully deciphered.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sirpa Kumpulainen and Daniel Svensson for providing a series of clay samples and corresponding characterization data.

Funding

Posiva Oy, Finland, provided funding for this study. Funding for open access publication was provided by the University of Bern.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Jebril HADI, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s42860-023-00254-4.