Introduction

On 24 February 2022, after months of tensions due to a sudden increase in its military build-up, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, precipitating a still ongoing war. The European Union (EU) found itself at a tipping point, confronted with a historic challenge to its longstanding commitment to peace and regional prosperity. The EU's heads of State and government were quick in framing the Ukrainian crisis as a common threat that urged a major response at the EU level. Within hours of the invasion, the European Council blamed Russia for its ‘unprovoked and unjustified military aggression’ and declared the EU's ‘unwavering support for the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine’ (European Council, 2022a). Although the invasion of Ukraine does not involve a direct military attack on the EU or any of its member states, Russia came closer to EU borders with all but a pacifist approach, thus giving rise to the ‘gravest threat to Euro-Atlantic security in decades’ (European Council, 2023). To this effect, the Russian escalation was controversially interpreted by some as the direct result of a decade-long NATO enlargement to Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet space, which Putin claimed was part of a strategy to move Ukraine away from Russia and closer to the West (Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer2014).

The Russian military aggression of Ukraine is thus yet another side of the ‘multiple crises’ the EU has been dealing with over the last couple of decades, attracting a widespread academic interest in the field of EU and party politics. Recent EU studies have discussed the consequences of the war for the European integration project, with a specific focus on security and defence policy as well as enlargement (Capati and Trastulli, Reference Capati and Trastulli2024; Genschel et al., Reference Genschel, Leek and Wens2023). In particular, scholarly research has examined its implications for EU governance, for instance underlying the enhanced potential for the European Commission to exercise forms of supranational entrepreneurship even in traditionally intergovernmental policy areas (Capati, Reference Capati2024). At the same time, the literature on party politics has investigated how the Russian–Ukrainian conflict has affected the foreign policy positions towards Putin's Russia by both single parties (Holesch et al., Reference Holesch, Zagórski and Ramiro2024) as well as party families (Guerra, Reference Guerra2024a), highlighting patterns of change or continuity (Kaniok and Hloušek, Reference Kaniok and Hloušek2023). Research in this tradition has shown, for instance, that party positions in the European Parliament vis-à-vis the Russian war in Ukraine largely depend on the ideological left–right cleavage as well as on attitudes towards European integration (Otjes et al., Reference Otjes, van der Veer and Wagner2023). Drawing on both literatures, this paper offers an analysis of the Ukrainian crisis' effects on EU-related party politics dynamics at the member state level. This research effort is ever more relevant as, in one respect, large-scale, exogenous crises in Europe have proved to increase the salience of European integration in the communication of national parties and to affect party positions on the EU's own policy response to them (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Popa and Schmitt2019); in another respect, party positions have been shown to be increasingly relevant in the conduct of the EU's foreign policymaking and in shaping EU external relations alike (Hofmann and Martill, Reference Hofmann and Martill2021).

The paper focuses on the Italian party system. On the one hand, the Belpaese has a longstanding cooperation with Russia, built on robust diplomatic, trade, and energy ties. Italian policymakers generally advocate for the involvement of Russia in the European security architecture, emphasising the need for the EU and NATO to maintain strategic communication channels with Moscow (Siddi, Reference Siddi2019). On the other hand, the Russian illegal annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 has made it difficult for Italy to sell the prospect of keeping Russia into Western cooperation structures to the Euro-Atlantic alliance. That prospect became even bleaker after the outbreak of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which pushed two consecutive Italian cabinets to negotiate and approve EU restrictive measures against Moscow. Those sanctions undermined bilateral trade, especially in the energy sector, thus raising pressures on the Italian government to lift economic sanctions, in particular from domestic industries most affected by them. This precarious equilibrium allows for variations in Italian political party positions vis-à-vis the EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The existing literature on Italian parties and the Ukrainian crisis has mainly focussed on right-wing formations due to their longstanding ties with Putin's regime (Morini, Reference Morini2023). Through an original dataset of tweets, Carlotti (Reference Carlotti2023) highlights how the ‘marriage of convenience’ between Italian right-wing populist parties and Putin's Russia, symbolising their opposition to centralised power in the EU, quickly gave way to a ‘divorce of convenience’ after February 2022, with Salvini's League toning down its pro-Putin rhetoric and Meloni's Brothers of Italy openly accusing the Russian Federation. Analysing media and social media data, Guerra (Reference Guerra2023) investigates Italy's far right and shows that while CasaPound condemned Russia for the outbreak of the conflict, Forza Nuova surprisingly shifted from a pro-Kiev to a pro-Kremlin position. Finally, widening the view to the Italian centre right and relying on public statements by political leaders, Terry (Reference Terry2024) finds that Silvio Berlusconi committed Forza Italia to reinforcing the EU's defence system and to providing European funds to Ukrainian refugees, but never mentioned direct military support to Kiev. So far, however, the literature has not provided a systematic analysis of Italian party positions towards the EU's own response to the war, one that accounts for the positions of all the main political formations on both the right, centre, and left of the political spectrum. This paper takes on this endeavour.

The remainder has the following structure. Section “Analytical framework: unpacking the EU’s response to the Ukrainian crisis and Italian party positions towards it” illustrates the paper's analytical framework and derives from it three research hypotheses to guide the empirical analysis. Section “Research design and data” presents the paper's research design, including its methodological approach and data. Section “Results” discusses the results of the empirical analysis. Finally, the “Conclusion” summarises the main findings, draws implications for future research and concludes.

Analytical framework: unpacking the EU's response to the Ukrainian crisis and Italian party positions towards it

The EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine

As the Russian–Ukrainian war broke out on 24 February 2022, it immediately triggered a joint reaction at the EU level. On the same day the Russian military aggression started, the EU heads of State and government gathered for a special European Council meeting to devise a comprehensive response to it. In that and later meetings (24–25 March and 30–31 May), four main areas of intervention were identified as urgent by EU leaders. The first concerns the adoption of major sanctions against Russia within the framework of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), in addition to those already in place following the Russian illegal annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in March 2014. To that effect, the European Council soon agreed on ‘further restrictive measures that will impose massive and severe consequences on Russia for its action’ (European Council, 2022a). Such measures, designed to weaken Russia's economic base and thus thwart its war efforts, covered the financial sector, energy, transport, and defence goods. When the heads of State and government reconvened for a European Council meeting in late March 2022, the EU had already issued its fourth package of restrictive measures against the Russian aggressor since the all-out invasion of Ukraine started. On that occasion, they urged all members to ‘align with those sanctions’ and warned against ‘any attempts to circumvent [them] or to aid Russia by other means’ (European Council, 2022b).

The second dimension in the EU's response to the war's outbreak consists in the provision of military support to Ukraine, also within the framework of the CFSP and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). On 27 February 2022, the EU foreign affairs ministers agreed on a €500 million military support package including €450 million in lethal arms and an additional €50 million in non-lethal equipment, such as fuel and first aid kits (Politico, 2022). EU military assistance to Ukraine was carried out within the framework of the European Peace Facility with the aim ‘to strengthen the capabilities and resilience of the Ukrainian armed forces and to protect the civilian population from the ongoing Russian military aggression’Footnote 1. At the European Council meeting of 30 and 31 May 2022, EU leaders reiterated their commitment to Ukraine's ability to defend its territorial integrity and sovereignty. In this respect, the European Council welcomed ‘the adoption of the recent decision of the Council to increase military support to Ukraine under the European Peace Facility’ (European Council, 2022c).

The third area of intervention relates to humanitarian support, and particularly the welcoming of Ukrainian refugees fleeing the conflict into the EU. Acknowledging that Russia's military aggression against Ukraine has led to an influx of millions of people seeking refuge in the Union, on 4 March the Council activated the temporary protection directive on a proposal from the European Commission. The temporary protection scheme allows displaced persons, who are not able to return to their country of origin, to enjoy harmonised rights across the EU, including residence, access to the labour market and housing as well as to medical assistance and education. On 24 and 25 March, the European Council praised ‘all the efforts made to welcome refugees fleeing the war in Ukraine’ and called ‘on all Member States to intensify their efforts in a continued spirit of unity and solidarity’ (European Council, 2022b). Taking stock of the refugee crisis in May 2022, the EU heads of State and government reconfirmed their commitment to the welcoming and protection of Ukrainians and invited the European Commission to mobilise resources to that effect (European Council, 2022c).

Finally, the fourth area of intervention entails granting Ukraine EU candidate status. On 28 February 2022, four days after Russia's invasion, Ukraine formally applied for EU membership, asking for a ‘new special procedure’ and an accelerated process. In its conclusions of March, the European Council acknowledged ‘the European aspirations and the European choice of Ukraine’ (European Council, 2022b) and invited the Commission to submit its opinion. In the meantime, the European Parliament also joined the leaders and called on all institutions to work towards granting EU candidate status to Ukraine (European Parliament, 2022). Following the Commission's opinion of 17 June on Ukraine's application for EU membership, the European Council granted candidate status to the country (European Council, 2022d).

Italian party positions vis-à-vis the EU's response to the Ukrainian crisis

As the EU's comprehensive response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine took shape between February and June 2022, it opened avenues for increased European integration in the fields of security (e.g. through the adoption of common sanctions), defence (e.g. through joint arms procurement), asylum (e.g. through the activation of common protection schemes) and enlargement (e.g. by granting Ukraine a membership perspective). In his seminal work on federalism, Riker argued that ‘the aggregation of resources for war is the primary […] motive for federation’ (Reference Riker and Hesse1996: 12). Building on that, in their recent research, Kelemen and McNamara (Reference Kelemen and McNamara2022) stressed that the EU's uneven political development can be explained by the protracted absence of war pressures or external military threats throughout the European integration process, which was mainly driven by economic and market-building dynamics.

Hence, the Russian–Ukrainian war potentially provides a ‘window of opportunity’ for increased European integration in the form of capacity-building and/or deeper policy coordination. Incidentally, the conflict has revamped debates on the establishment of a European army to defend EU borders along with, or in alternative to, NATO, while efforts in this direction have been hampered by intergovernmental institutions and domestic preferences alike (Fiott, Reference Fiott2023). With the theorised shift from ‘permissive consensus’ to ‘constraining dissensus’, European integration issues have assumed increasing salience for national party competition, and decisions about further EU integration have come to affect national party positions domestically (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). In this respect, the EU's response to the Ukrainian crisis was the subject of intense political debate and even outright contestation in the Italian party system, with political parties taking often divergent positions along the four areas of EU intervention.

To explain such divergent positions, we first draw on cleavage theory and the party family literature. Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) famously made the case that contemporary European party systems are the result of historical conflicts or ‘cleavages’ about state-building, class and religion that have come to define quite stable party identities and patterns of political competition, including the national and the industrial revolutions. In an effort to make sense of the variety of political formations stemming from such historical cleavages, subsequent studies have classified parties into party family groupings, mainly based on their ideological connotation (von Beyme, Reference von Beyme1985). Since the 1980s, and building on Rokkan's (Reference Rokkan1970) own development of cleavage theory, the party family approach has thus established itself as a common analytical framework to investigate party and party systems across time and space. While the influence of the traditional cleavages identified by Lipset and Rokkan might have waned over time, especially for what concerns voter behaviour, those cleavages have proved to retain the potential to condition the way political parties respond to rising issues (Borbáth et al., Reference Borbáth, Hutter and Leininger2023).

In this respect, investigating the impact of the European integration process on national competition dynamics, studies on cleavage politics have highlighted how the positions of political parties towards the EU in fact tend to vary depending on their ideological orientation (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016). In particular, they have contended that party attitudes towards the EU are filtered by political parties' deeply rooted ideologies, reflecting long-standing commitments on key domestic issues. As a consequence, European integration has been assimilated into pre-existing orientations of party leaders and members, operating as structural constraints for party positions on the EU (Marks et al., Reference Marks, Wilson and Ray2002). Work in the tradition of the cleavage approach has thus suggested that the same party families across national boundaries tend to share the same position with respect to the European issue, and that membership in a party family largely determines party positions towards the EU (Marks and Wilson, Reference Marks and Wilson2000). Based on the above, we raise the following research hypothesis:

[H1] Italian political parties belonging to the same party family will share similar positions on the EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine

In predicting party positions towards the EU based on ideology, the literature has resorted to the analytical differentiation between mainstream and radical or extreme party families. Mainstream parties, which are defined as ‘the electorally dominant actors in the centre-left, centre and centre-right blocs on the Left-Right political spectrum’ (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002), include most Social Democratic, Christian Democratic, Liberal and Conservative formations. These are generally much more supportive of European integration than radical parties on both the left and right of the political space, which tend to share Euroscepticism as a common trait. Indeed, mainstream parties are mostly government parties, as such having promoted and contributed to advancements in European integration for quite a long time. Mainstream parties have historically taken centre stage in the launch and advancement of the customs union, single market and monetary integration, thus incorporating pro-Europeanism into their traditional ideological apparatus (Capati and Improta, Reference Capati and Improta2021).

Interestingly, cleavage theory suggests that mainstream parties have shied away from the growing politicisation of the European integration issue, as the long-standing system of social cleavages has constrained their attitudes towards the EU (Carrieri, Reference Carrieri2020). As a matter of fact, mainstream parties largely control the pro-European transnational lists in the European Parliament, including the European People's Party (EPP), the Party of European Socialists/Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (PES/S&D), the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe/Renew Europe (ALDE/RE), and the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens-EFA). Because of their ideological homogeneity vis-à-vis the EU issue, these parties are generally known as ‘mainstream pro-European parties’ (Carrieri, Reference Carrieri2020).

On the contrary, radical and extreme parties on both the left and right have used their anti-EU character as an additional dimension on which to build their political opposition to mainstream parties in positions of power (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Popa and Schmitt2019). Radical and extreme left parties oppose the idea of a neoliberal Europe based on fiscal discipline and austerity policies as a major threat to national welfare systems and redistribution principles. Their opposition to the current model of European integration thus mainly takes place along economic lines as they view the EU's economic and monetary union as a means for neoliberal elites to accumulate wealth at the expense of the working class, undermining the core values of socialist ideology (De Vries and Edwards, Reference De Vries and Edwards2009).

On their part, radical and extreme right parties have traditionally been concerned with the protection of national sovereignty and independence vis-à-vis external or supra-national entities (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), especially in the realm of ‘core state powers’ such as security and defence (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014). To this effect, these parties ‘are against EU integration as such’, that is as a form of supranational delegation eroding national identity and ‘cultural, economic and political sovereignism’ (Carrieri and Vittori, Reference Carrieri and Vittori2021: 957). This form of unconditional Euroscepticism has been assimilated into the longstanding ideological apparatus of far-right parties, which have increasingly emphasised their opposition to the EU as a strategic tool to attract mainstream parties' voters (Fabbrini and Zgaga, Reference Fabbrini and Zgaga2023). Parties in this tradition have thus put forward proposals for a ‘Europe of the People’, based on the principles of inclusiveness and democracy, which runs in opposition to the ‘Europe of bureaucrats’ with a view to appealing to the disaffected voters of mainstream parties.

Overall, the dynamics of party positioning along the left-right continuum and towards European integration can be visualised as an inverted U-shaped curve whereby support for the EU tends to be lower in the peripheries of the political spectrum (in correspondence of far left and far right parties) and higher at its centre (in correspondence of mainstream parties) (Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson, Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). In light of the foregoing, we raise the following research hypothesis:

[H2] Italian mainstream parties will support the EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, while radical and extreme parties will oppose it

Finally, while part of the literature continues to look at European integration as a single phenomenon, without a distinction of sorts between types of EU issues, some scholars have shed light on its multidimensional character (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005). In particular, studies in this latter tradition have highlighted how the degree of contestation of EU-related issues by national political parties tends to vary depending on their nature as either ‘constitutive’ or ‘policy’ issues (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Hutter and Kerscher2016). Constitutive issues, which are long-term by definition, are those concerning the EU as a polity, touching upon aspects related to the external boundaries of the political community (such as the EU's borders as influenced by enlargement policy) or its internal composition (such as the inclusion and integration of non-EU country nationals into the Union's territory by means of the EU's migration and asylum policy).

As for the latter, although solidarity towards Ukrainian refugees was specifically activated through the temporary protection directive (TPD), which is in itself a contingent, short-term policy measure, the granting of asylum rights to them has apparent long-term implications for the EU as a political community. As the war drags on, Ukrainian workers will integrate into the EU's labour market, contributing to the European workforce in several sectors. After the TPD expires, this will facilitate their transition to permanent residency permits based on employment, family reunification or humanitarian grounds. Also, the TPD contains provisions aimed at ensuring the integration of Ukrainian children into the education system of EU member states, meaning they can attend local schools with their peers from the host country, fostering a sense of inclusion and contributing to long-term social cohesion. Ukrainian children integration into the EU's education system makes for their continuous residence in the Union's territory, language proficiency in the host country's official language(s) and knowledge of the country's laws and customs, conditions which offer clear pathways to naturalisation (citizenship).

Constitutive issues are thus about the constitution of Europe itself, ‘including the distribution of powers to the various organs, as well as questions relating to enlargement and further integration’ (Mair, Reference Mair2000: 45). By contrast, policy issues are generally short- to medium-term, and concern aspects of public policy in the more functional sense. Policy issues relate to the day-to-day policymaking in the EU and involve the main activities of EU institutions in both the supranational and the intergovernmental realm (Mair, Reference Mair2000), this latter including foreign, security and defence policies such as sanctions and arms delivery. Contrary to constitutive issues, polity issues concern the daily functioning of Europe and do not affect what or who gets to constitute the EU as a political community.

Along these lines, the literature has argued that, in addition to a trade-off between emphasising the EU or national issues in their political communication, parties are also confronted with a choice as to what type of EU issues to emphasise. While existing studies tend to focus on party discourse concerning the constitutive aspects of European integration (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2007), a significant degree of both salience and contestation in EU-related party communication strategies has been shown to be associated with policy issues instead. This is particularly true for direct party communication, such as that taking place through party manifestos or press releases, rather than for indirect or mediatised communication, which still tends to mostly attract discourse on constitutive issues (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Hutter and Kerscher2016). To this effect, when it comes to direct communication channels, the greater salience attributed by political parties to policy issues is likely to come with a greater scope for party contestation about those very issues, as opposed to expected party convergence about constitutive issues with a lower political salience (Capati, Improta, and Trastulli, Reference Capati, Improta and Trastulli2024). We thus raise this final hypothesis:

[H3] In the EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, constitutive issues are less salient for, and contested by, Italian political parties than policy issues by means of direct communication

Research design and data

This paper carries out a qualitative content analysis of Italian parties' Facebook posts through the assistance of the software NVivo. The qualitative content analysis took the form of a ‘thematic analysis’ (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1998) in the first stage of the process, whereby the relevant dimensions of the EU's response to the Russian war were inductively identified through an in-depth reading of EU official documents between February and June 2022; later, it turned to a ‘claim analysis’ (Koopmans and Statham, Reference Koopmans and Statham1999) of Italian parties' Facebook posts.

Qualitative content analysis can be used ‘for systematically describing the meaning of qualitative material by classifying data as instances of the categories of a coding frame’ (Schreier, Reference Schreier2012: 1). To this effect, it allows for the interpretation of textual data through the lenses of a pre-established theoretical or analytical framework, and consists in a set of systematic methodological steps that ensure the validity and reliability of results. First, based on the research's objectives, an analytical codebook was elaborated to provide us with a set of rules governing the analysis of the selected data. The codebook includes codes, hierarchically organised in main categories and sub-categories; definitions for all main categories and sub-categories of codes; and coding examples, or excerpts of data coded to the main categories and sub-categories.

Through a thematic analysis, we inductively identified as codes nineteen Italian political parties and four dimensions of the EU's response to the Ukrainian crisis. In turn, political parties were deductively organised into nine party families (Extreme Left/Communist, Radical Left/Democratic Socialist, Centre-Left/Social Democratic, Centrist, Centre-Right/Christian Democratic, Radical Right/Conservative, Extreme Right/Neofascist, Green, and Other) as well as along the mainstream/Eurosceptic divide, while the four dimensions were deductively divided into EU constitutive (enlargement to Ukraine and welcoming of Ukrainian refugees into the EU) and policy issues (arms delivery to Ukraine and sanctions against Russia)Footnote 2. Finally, consistently with claim analysis, the sub-categories pro and against were identified for each of the four dimensions in the EU's response to the war in order to investigate the specific party positions along the said EU constitutive and policy issues (see the full codebook in Table A1 in the Appendix).

Second, using the Meta-owned CrowdTangle database for academic research, we collected all Facebook posts by Italian political parties for a three-month period starting from the outbreak of Russian military operations in Ukraine on 24 February 2022, until 24 May 2022 (N = 7218)Footnote 3. To retrieve the relevant posts, we searched for stemmed keywords such as ‘sanctions’, ‘weapons’, ‘enlargement’ and ‘refugees’. We thus manually coded the posts' textual content to the party which published it and to the relevant constitutive or policy dimension of reference, specifying (whenever possible) whether the post was pro or against that particular instance of the EU's response to the Ukrainian crisis. To this effect, implementing the logic of claim analysis, we analysed Italian political parties' Facebook posts in order to identify ‘claiming’ actors and their arguments. Specifically, we first identified who was making the claim, that is the Italian political party behind the Facebook post, and secondly coded the claim included in the Facebook post to the relevant dimension of the EU's response to the Russian–Ukrainian war. This resulted in 390 coded posts, amounting to 5.40% of the original sample.

Facebook is excellent for assessing Italian party positions on the EU in the context of the Ukrainian crisis as parties use it to communicate with the wider public, contrary to electoral manifestos. As the literature suggests, while of itself party positioning on specific policy issues follows internal deliberations and ideational confrontation between party leaders and rank-and-file members, parties strategically communicate their positions externally (De Sio et al., Reference De Sio, De Angelis and Emanuele2017). This requires ‘the expansion of debates from closed elite-dominated policy arenas to wider publics, and here the mass media plays an important role by placing political actors in front of a public’ (Statham and Trenz, Reference Statham and Trenz2013: 3). Moreover, Facebook posts are direct and unmediated, signalling what parties actually want to communicate rather than what the media consider interesting to report (Horn and Jensen, Reference Horn and Jensen2023).

Results

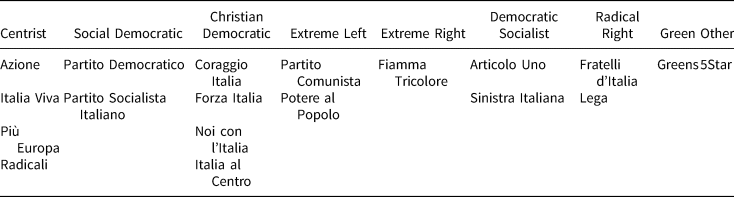

Table 1 below summarises the categorisation of Italian parties across the several party families (see also Table A1 in the Appendix)Footnote 4.

Table 1. Categorisation of Italian parties across party families

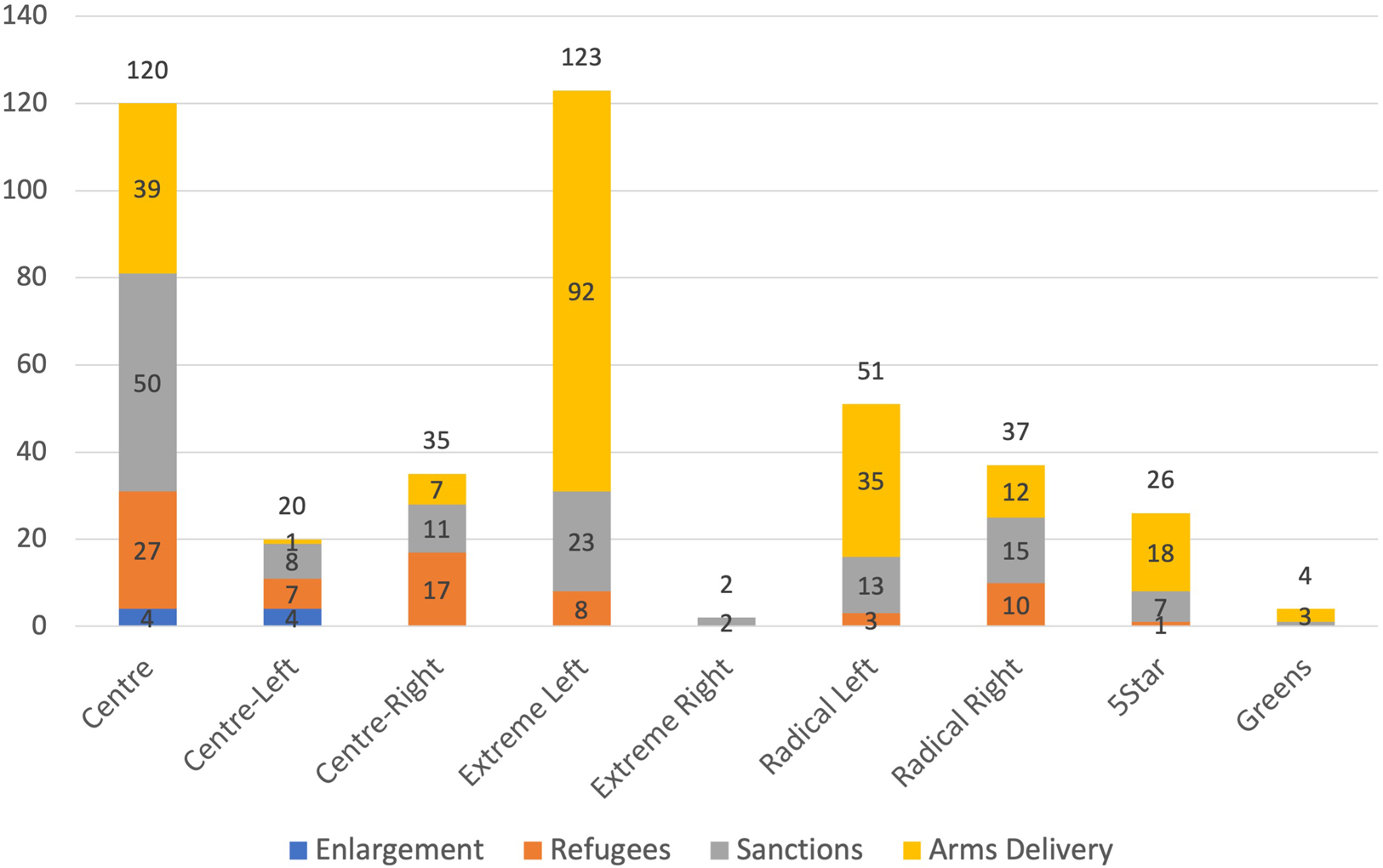

Before testing our research hypotheses, the content analysis at once offers preliminary descriptive insights into the salience of the four dimensions of the EU's response to the Ukrainian crisis for Italian parties in their Facebook-based communication (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Total number of coding references to the four dimensions of the EU's response to the war by party family.

The party families that posted more frequently on the EU's response to the war in the selected timeframe were the Extreme Left (123 references) and the Centrist (120). These were followed by the Democratic Socialist (51 references), the Radical Right (37) and the Christian Democratic (35) party families, while the 5Star Movement, the Social Democrats and the Greens lagged far behind, with 26, 20, and 4 references respectively. Finally, the Extreme Left only featured 2 references to any of the identified dimensions across the timeframe of reference (Table A1 in the Appendix).

The Extreme Left involved an almost equal number of posts from both Potere al Popolo (55) and Partito Comunista (52), while the Centrists were driven by Italia Viva (71) and included a minor number of posts from Più Europa (24) and Azione (6). The Democratic Socialists and the Radical Right were also internally very asymmetric, with Sinistra Italiana (35) and Lega (32) posting on the EU's response to the Russian invasion significantly more than Articolo Uno (4) and Fratelli d'Italia (1) respectively. While the four-pronged Christian Democratic party family only featured posts from Forza Italia (25) and Italia al Centro (5), both the Social Democrats and the Extreme Right included posts from just one party, that is Partito Democratico (17) and Fiamma Tricolore (2) respectively. Finally, the 5Star Movement and the Greens featured 45 and 15 posts each (Table A2 in the Appendix).

Following this preliminary overview, it is possible to test H1 only against those party families in which at least two different parties posted on the same dimensions of the EU's response to the war in Ukraine. This methodological requirement in and of itself excludes the Social Democrats and the Extreme Right from the possibility of empirical falsification with respect to H1. Figures 2 below presents a visualisation of the findings with respect to all other party families.

Figure 2. Total number of coding references in favour and against the four dimensions of the EU's response to the war for political party by party family.

Within the Extreme Left, both Partito Comunista and Potere al Popolo took a very clear stance against arms delivery to Ukraine, with 39 and 53 references respectively, as well as against the adoption of sanctions against Russia, including 15 and 8 references to this effect. Remarkably, neither party featured any references in favour of arms delivery nor sanctions. However, while the issue of Ukrainian refugees fleeing the conflict was much less salient in their public communication (5 total references), they appeared to be on opposite sides of the divide, with Partito Comunista against and Potere al Popolo in favour of welcoming Ukrainian asylum seekers into the EU. The Centrists showed coherence across all dimensions of the EU's response to the war they posted on, with Azione, Italia Viva and Più Europa invariably supporting EU enlargement to Ukraine (4 total references), welcoming Ukrainian refugees (23) and issuing economic sanctions against Russia (47); and Italia Viva and Più Europa also communicating their approval of arms delivery to Ukraine (35 total references). The Christian Democrats both posted in favour of arms delivery to Ukraine, with three references by Forza Italia and four references by Italia al Centro along these lines. Similarly, within the Radical Right, both Fratelli d'Italia and Lega supported the welcoming of Ukrainian refugees into EU borders, with nine total references in this direction and none to the contrary. Finally, the Democratic Socialists all opposed arms delivery to Ukraine while supporting restrictive measures against Russia.

With the minor exception of the Extreme Left's disagreement over the welcoming of Ukrainian refugees into the EU, which can be explained by the contingent protests by a group of Ukrainian migrants against the Portuguese Communist PartyFootnote 5 and by its structural anti-Ukrainian and ‘Red-Brownism’ approach (Guerra, Reference Guerra2024b), all parties belonging to the same party family appeared to share similar positions on the EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine with respect to both constitutive and policy issues. Notably, the perhaps surprising support of both radical right parties – Fratelli d'Italia and Lega – for the welcoming of Ukrainian refugees into the EU could be explained precisely by their longstanding ideological opposition to migration from non-European countries, as their Facebook posts stressed the different natures of the two occurrences as a matter of solidarity towards ‘asylum-seekers’ fleeing an unjustified war and as a matter of illegal migration at the service of ‘smugglers’ business' respectivelyFootnote 6. At the same time, other contributing factors may have played a role to this effect, such as the governing status of these parties during the analysed timeframe, which may have increased their responsibility pressures (vis-à-vis other EU member state governments) as opposed to responsiveness considerations (vis-à-vis their voters), especially in the face of a large-scale crisis (Karremans and Lefkofridi, Reference Karremans and Lefkofridi2020). In this last respect, although government status can indeed largely explain Italian party positions on the EU's response to the war, with the exception of the League's opposition to arms delivery while in government, opposition status is not a good explanatory factor, as opposition parties were divided with respect to arms delivery, refugee protection and sanctions (see Figure A1 in the Appendix). Overall, the analytical category of the party family thus proved to be a good (and better) explanatory factor behind Italian party positions vis-à-vis the EU's reaction to the Ukrainian crisis. This confirms the validity of H1 [Italian political parties belonging to the same party family will share similar positions on the EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine].

H2 is more ambitious in terms of explanatory power with respect to H1 in that it implies a larger number of parties sharing similar positions with respect to the party family divide. In other words, once party families are shown to be powerful analytical categories to explain Italian party positions with respect to the EU's approach to the Ukrainian war, the paper tests whether all party families on the same side of the mainstream/Eurosceptic divide still have similar positions on the identified constitutive and policy issues. Figure 3 below illustrates the findings in this respect. Mainstream parties did share the same positions with respect to constitutive issues, invariably supporting enlargement to Ukraine (eight references in favour, none against) and the welcoming of Ukrainian asylum seekers (49 references in favour, none against). However, looking at policy issues, while strongly in favour of sanctions against Russia (net of two posts against sanctions, both by Sinistra Italiana, which still was in favour of sanctions overall), mainstream parties were deeply divided vis-à-vis sending weapons to Ukraine (43 references in favour, 44 against), which was supported by Partito Democratico, Forza Italia, Italia al Centro, Italia Viva and Più Europa but strongly opposed by Articolo Uno, the Greens and Sinistra Italiana. At the same time, Eurosceptic parties shared the same positions on welcoming Ukrainian refugees (14 references in favour, two against by Partito Comunista) and on arms delivery (123 references against, three in favour by the 5Star Movement, which was overall against arms delivery too), but were divided over sanctions against Russia (27 references against, 13 in favour), with Fiamma Tricolore, Partito Comunista and Potere al Popolo opposing them and 5Star Movement and Lega in favour.

Figure 3. Total number of coding references in favour and against the four dimensions of the EU's response to the war by mainstream and Eurosceptic parties.

Overall, the mainstream/Eurosceptic divide does not explain Italian party positions towards the EU's response to the Russian–Ukrainian war. On the one hand, both mainstream and Eurosceptic parties approved the EU's response in terms of constitutive issues, with Eurosceptic parties supporting access into the EU for Ukrainian asylum seekers and mainstream parties explicitly backing enlargement to Ukraine too. On the other, mainstream and Eurosceptic parties were internally divided vis-à-vis one of the two major policy issues, that is arms delivery and sanctions respectively. In sum, while mainstream parties uniformly supported sanctions against Russia, their position towards sending weapons to Ukraine was much more contested. Along the same lines, Eurosceptic parties were united in opposing arms delivery, but some of them favoured sanctions against Russia. This contributes to disconfirming H2 [Italian mainstream parties will support the EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, while radical and extreme parties will oppose it]. The limited explanatory capacity of the mainstream/Eurosceptic divide may again be due to the ideological differences within both Europeanist and Eurosceptic parties, which proved to largely account for Italian party positions towards the EU's response to the Russian invasion. For instance, among mainstream parties, the Democratic Socialists (Articolo Uno and Sinistra Italiana) and the Greens unsurprisingly opposed arms delivery based on their ideological pacifism and anti-militarism. The Greens often made de-militarization and the fight against emission-intensive arms industries the cornerstone of their political programmes. At the same time, left-wing parties generally prioritise social welfare and public investments, arguing that funds used for military aid would be better spent on humanitarian assistance, housing, or health care. Among Eurosceptic parties, the League's support for EU sanctions against Russia can instead be explained – through an attentive reading of the party's Facebook posts – by its radical opposition to arms delivery, which left supporting sanctions as the only credible policy option to hinder Russian war effortsFootnote 7.

Turning to H3, Figures 4 and 5 below show empirical results with respect to constitutive issues and policy issues' salience and contestation respectively. In terms of salience, policy issues were much more emphasised by Italian political parties in their Facebook communication than constitutive issues. Arms delivery was the single most salient issue across the four identified dimensions of the EU's response to the Russian aggression, featuring a total of 207 references and a prominence of the Extreme Left (92 references). Arms delivery was followed by sanctions, a policy issue too. Party discourse on sanctions against Russia registered 130 references, partly driven by posts by the Centrists (50 references). Constitutive issues, most notably enlargement but also the question of refugees, lagged far behind in Italian parties' Facebook-based communication, totalling eight and 73 references respectively. In particular, enlargement was only discussed by the Centre (4 references) and the Centre-Left (4).

Figure 4. Total number of coding references to constitutive and policy issues by party family.

Figure 5. Total number of coding references in favour and against constitutive and policy issues by party family.

Consistently with the above, party contestation proved much higher in relation to policy rather than constitutive issues. While virtually every political formation supported the EU's constitutive response to the war, Italian political parties took very different stances with respect to its policy response, with 196 total references against and 131 in favour. Statements against the EU's policy response to the crisis, including on arms delivery and sanctions, were driven by the Extreme Left (115 references) and the Radical Left (37), while those in favour were driven by the Centrists (82). These findings confirm the validity of H3 [In the EU's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, constitutive issues are less salient for, and contested by, Italian political parties than policy issues by means of direct communication]. The findings are also consistent with an alternative explanation: as soft security policies, asylum and enlargement are less controversial than sanctions or arms delivery because they largely come down to the activation of solidarity mechanisms in favour of Ukraine and Ukrainians that are always welcome by the public. On the contrary, as hard security policies, sanctions and arms delivery consist in harming Moscow (either directly by means of economic sanctions or indirectly by means of military assistance to Ukraine), and can thus spur retaliation (e.g. in the form of cuts in energy supplies), thereby increasing the perceived risks of military de-escalation between Russia and the West (Truchlewski et al., Reference Truchlewski, Oana and Moise2023).

Conclusion

This paper has analysed Italian party positions on the EU's response to the Russo-Ukrainian war, singling out the adoption of sanctions against Russia, the provision of military support to Kiev, enlargement to Ukraine and the welcoming of Ukrainian refugees into the EU as the four main dimension of such a response. In doing so, the paper has filled a gap in the literature on EU-related party competition dynamics in the immediate aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This research has drawn on the literatures on cleavage politics, the inverted U curve and the differentiated forms of politicisation, and tested theory-driven research hypotheses through a qualitative content analysis of Italian parties' Facebook posts in the three months following the outbreak of the conflict. In an effort to contribute to these literatures, the analysis has led to three main findings.

First, party families are a good explanatory factor behind Italian party positions vis-à-vis the EU's response to the war outbreak as parties belonging to the same family shared a similar stance on the four dimensions of such a response. The only exception to this effect concerned the Extreme Left and the issue of refugees. While Potere al Popolo supported the welcoming of Ukrainian migrants, Partito Comunista voiced opposition to it due to contingent factors, most notably a series of protests by Ukrainian migrants against the Communist Party in Portugal, as well as structural factors, such as its so-called ‘Red-Brownism’ approach. Incidentally, the relatively small Italian Communist Party was the only political force to make public claims in favour of Putin's Russia, which constitutes a clear watershed between Italy's First Republic, largely polarised along the West-Soviet axis, and the Second Republic. Second, the Europeanism/Euroscepticism divide does not explain Italian party positions on the EU's reaction to the Ukrainian crisis. For one thing, all parties across the political spectrum supported access of Ukrainian refugees into the Union's territory. For another, Europeanist parties split over the provision of arms to Kiev about as much as Eurosceptic parties split over the adoption of sanctions against Moscow. Third, policy issues in the EU's response to the war (such as sanctions and arms delivery) were much more salient for and contested by Italian political parties than constitutive issues (such as enlargement and asylum). While Italian parties posted relatively little about enlargement and asylum, and almost invariably supported the EU's actions in those respects, they emphasised sanctions and arms delivery in their Facebook-based communication, which paved the way for a higher degree of contestation of these issues. To this effect, the Extreme Left and the Radical Left were the main opponents of the EU's policy response to the war, whereas the Centrists stood up as its main supporters.

These findings open several avenues for future research. The paper examines a time span coinciding with the early aftermath of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, where political parties quickly had to make sense of the unfolding of the escalation and react to the EU's immediate response to it. However, as the literature on party/voter cueing shows, in the medium- to long-term parties tend to respond to public opinion on issues related to European integration. For this reason, longitudinal analyses are needed to establish whether and how voters' preferences affect party positions on the EU with respect to the ongoing conflict at its later stages. In another respect, while the present paper focusses on the Russia-Ukraine war, underscoring its multifaceted and composite character, future comparative research should assess the scope of our findings against crises of a distinct nature or touching upon other policy areas. To this effect, for instance, the recent COVID-19 pandemic offers an ideal comparative benchmark, especially as it involved the mobilisation of different EU actors and governance mechanisms, which may ultimately affect the way political parties interpret and take position on EU crisis management measures. Finally, because the paper's single case study poses limitations on our ability to generalise the above findings, further work should investigate the effects of the Russian military aggression of Ukraine on party competition dynamics in other EU member states, starting from those featuring a different party system structure, political polarisation as well as historical economic and diplomatic relations with Moscow. Such an effort would provide us with a better understanding of the conditions under which individual parties or party families are expected to support or oppose EU's policies in times of crisis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Luiss University within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was funded by REGROUP (Rebuilding Governance and Resilience out of the Pandemic), a Horizon Europe's project under Grant 101060825.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2024.18

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Marco Improta, Elisabetta Mannoni and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on a previous version of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.