On February 19, 1915, Heinrich Resch gave a lecture to a group of military doctors at the Bayreuth Garrison on the topic of “Mental Illnesses and War.” Resch, a psychiatrist working at the mental hospital in Bayreuth, began by observing that a rich literature on mental illness during the war had already emerged across a variety of media. He then noted that articles appearing in the daily newspapers “consistently tend to have an enlightening and partly calming effect on readers.” This was, in Resch's view, “surely not unnecessary:”

Because if we take only the daily newspapers from the first days of the mobilization, there we read about many suicides, about many mental disorders [Geistesstörungen] which have allegedly occurred or arisen out of worry for relatives being pulled to the front and fear of an enemy invasion on German soil. We read among the death notices about the sudden and unexpected death of a young, powerful officer or a tried-and-true military official.

For this reason, Resch thought the question, “Does a war really have an influence on mental illness?” must “absolutely be answered with ‘yes.’”Footnote 1

In many ways, Resch's observations about the mental and emotional distress with which many Germans greeted the outbreak of war are unsurprising. It has now been more than two decades since a group of revisionist historians definitively dismantled the narrative that a widespread, bellicose “war enthusiasm” gripped Europeans in July and August of 1914, instead pointing to the complex, dynamic, and often contradictory emotions and reactions displayed at the outbreak of the war.Footnote 2 German “war enthusiasm,” to the extent it existed, was an almost entirely urban, middle-class phenomenon—albeit one that often transcended gender lines—found principally among the educated youth. Nonetheless, the myth of a universallyly felt “spirit of 1914” attained “widespread acceptance” during the conflict, in large part because it served as a national narrative Germans could unite around as a way to give meaning to the newly begun war.Footnote 3 As Jeffrey Verhey summarizes, “The essence of the August experiences was not so much enthusiasm but excitement, a depth of emotion, an intensity of feeling.” Ultimately, “The Germans united, not in their enthusiasm but in their purpose.”Footnote 4 Subsequent research has further solidified this characterization with only slight modifications.Footnote 5

What Resch's observations highlight, however, is that there were, at a minimum, three other noteworthy—and noted—phenomena occurring simultaneously in August 1914. Alongside the cheering crowds and patriotic rhetoric were “many” suicides, combat deaths, and instances of intense emotional distress at both the potential and actual lethal consequences of the newly begun conflict. Indeed, if the current was one “of a widespread popular support for the war based on resignation, acceptance, sometimes despondency, and later a growing resolve,” as Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau and Annette Becker aptly summarize it,Footnote 6 then the undercurrent centered on self-destruction, mass death, and the resultant emotional trauma. Further, the Bayreuth psychiatrist at least implicitly understood that all three elements were not only concurrent, but inherently interrelated. Together, they constituted a thanatological nexus at the center of Germans’ new quotidian reality that rendered “enlightening” and “partly calming” newspaper articles “not unnecessary.” It is thus all the more striking that while the latter two elements in Resch's triad have received a great deal of attention, the suicides of 1914 have virtually no presence in the historiographical record at all.Footnote 7

Here, however, I examine the “spirit” and the suicides of 1914 together in the context of Germany's spontaneous mobilization for war. I approach this nexus as what the essayist and Auschwitz survivor Jean Améry later termed an “inclination toward death” (Todesneigung): a continuum of self-destructive behaviors, at the far-end of which is explicit self-destruction—instances of self-aware self-death recorded as such by contemporaries.Footnote 8 But this continuum encompasses much more than the expressly or obviously suicidal, including, importantly, behaviors that are overtly oriented toward life, but nonetheless inclined toward death: that is, cases of implicit self-destruction. This includes those, in the most extreme instances, whose self-destruction was conditioned entirely externally, by the state.Footnote 9 Thus, in contrast to the Freudian concept of the “death drive” (Todestrieb), Améry's analytic and its central geometric metaphor emphasizes behavior and external socio-historical factors that condition self-destruction before internal psychological dynamics.

Approached in this way, it becomes clear that the suicides and combat deaths Resch noted were part of a common spectrum of wartime self-destruction whose effects reverberated widely throughout German society. What emerged rapidly in August 1914 was a constellation of behavioral inclinations toward death, conditioned generally by the German state and more particularly and immediately by the army, sitting within the broad socio-moral consensus of the “spirit of 1914.” I argue that the recorded suicides from the war's opening month illustrate the intense social, emotional, and moral dislocation, confusion, and anxiety directly engendered by the German state's decision for war. While these suicides remained exceptional and extreme acts, in their extremity they formed a counter- or “shadow” vanguard to the “enthusiastic” crowds of that summer: a pessimistic counterpoint to the optimism of the war's early days. This shadow vanguard was then a harbinger of the mortal stakes of the conflict, both personally and politically, which highlighted key social, moral, and emotional vectors of the ultimate collapse of the empire's legitimacy in 1918. But the suicidal substrate—the undercurrent of self-aware self-death—extended far beyond this shadow vanguard and actually included the quintessential “war-enthusiastic” figure: the war volunteer (Kriegsfreiwilliger). Although not recorded or understood as explicitly suicidal, volunteering for military service was the most prominent form of a widespread set of implicitly self-destructive behaviors, as the thousands of men who rushed to the colors that August did so despite widespread public knowledge of the new war's massive lethality. The personal self-destructiveness of the entire enterprise was in turn buried under and concealed by its emotional experience as a Pflichtgefühl—literally a “feeling of duty”—and moral coding as national sacrifice in line with the “spirit of 1914” by both state and nonstate actors. The specific suicidal nature of the actions which that “spirit” called for was thus rendered largely invisible, as the emotionally powerful surface current imbued the new thanatological reality with a broadly palatable, transcendent meaning. In August 1914, for millions of Germans, personal self-destruction “became” national sacrifice as the country embarked on the war that would ultimately destroy the Kaiserreich.

Explicit Self-Destruction: The Suicides of 1914

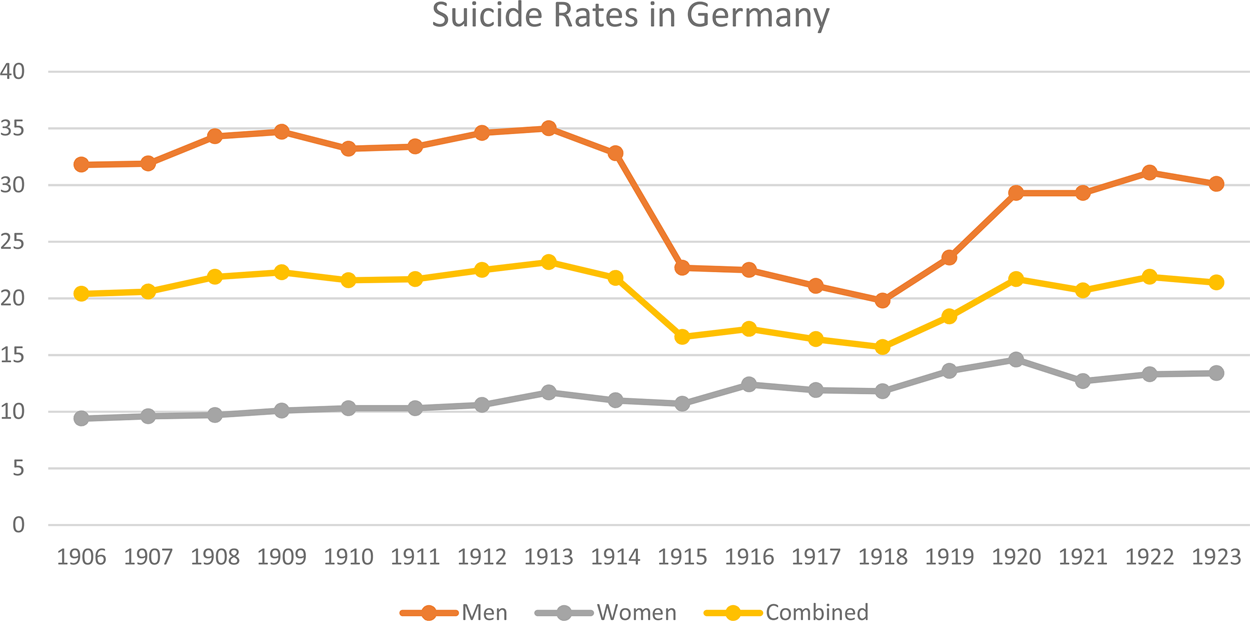

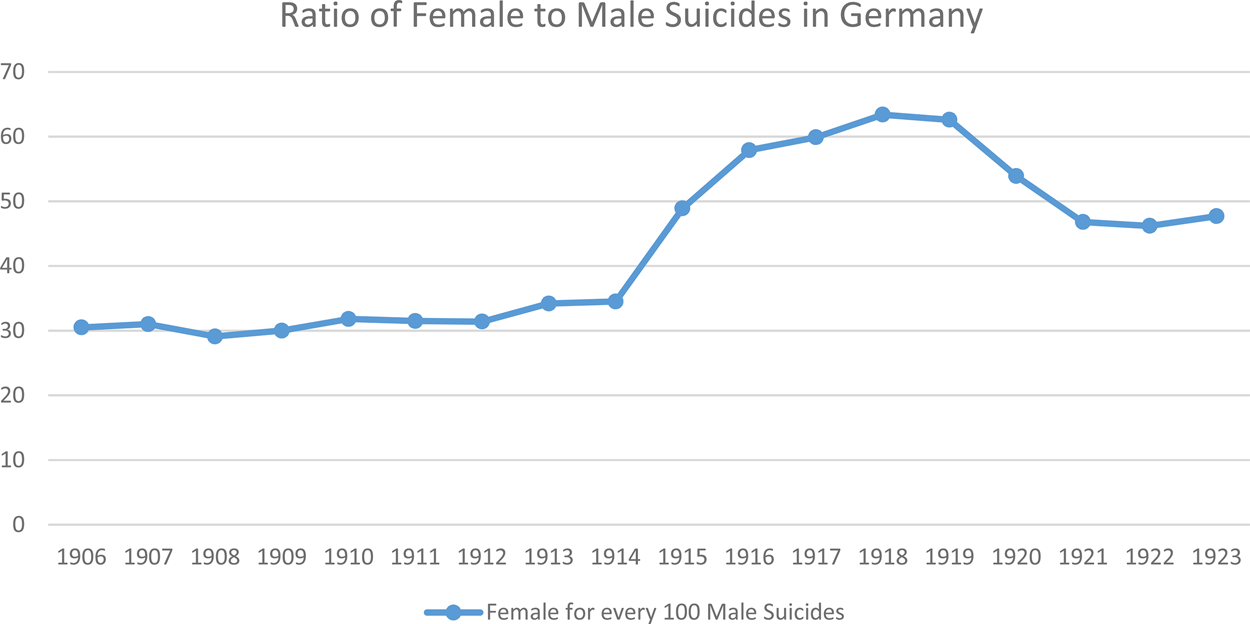

Although they remain only suggestive, not definitive, the surviving suicide statistics provide an overview of the extreme end of the self-destructive spectrum and sketch its macro-level contours—explicit suicide in collective silhouette.Footnote 10 According to the Statistical Office of the Reich (Statistischen Reichsamt), the national suicide rate (Figure 1) decreased in 1914, with the rates for men and women falling comparably, though men killed themselves significantly more often than women did. But while the male suicide rate continued to decrease over the course of the war, the female rate actually increased beginning in 1916, when it reached its peak and ended just above the 1913 rate at the war's end. The ratio of female-to-male suicides puts this macro-level dynamic into even greater relief (Figure 2). Although there were only 34.5 female suicides for every 100 male suicides in 1914, over the next four years, the ratio increased to 63.4 per 100, a jump of 83.8 percent. These numbers suggest that while the war was undoubtedly traumatic for both men and women, the chronological distribution of that collective suffering differed greatly. At the explicit end of the suicidal spectrum, enduring the continuing war proved most difficult for women, while men found the outset of the war the most arduous and unendurable.

Figure 1 (Data Source: Statistischen Reichsamt, Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Bd. 276 (1922): 393; Statistischen Reichsamt, Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Bd. 316 (1926): 34*):

Figure 2 (Data Source: Statistischen Reichsamt, Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Bd. 276 (1922): 393; Statistischen Reichsamt, Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Bd. 316 (1926): 34*):

But however small the numbers, women's suicidal agony was not negligible at the start of the war. For some, the very fact of a husband, son, or other loved one heading to the front proved too much to bear. The neurologist Emil Redlich recounted an anecdote in a 1917 article wherein a forty-three-year-old man, called up at the beginning of August 1914, witnessed, on the day of his presentation, “the suicide of an enlisted reservist's wife, who, after bidding farewell to her husband, threw herself under the wheels of the departing train.”Footnote 11 Such incidents brought together all three elements in Resch's triad—suicide, (potential) combat death, and mental distress—and appear to be the kinds of events he had in mind when acknowledging the need for “enlightening” and “partly calming” articles in the daily newspapers. Especially considering that this was an act committed in public at precisely the time and place most often home to “war enthusiasm” as it manifested that August, it becomes clear that, however statistically exceptional, such acts had a disproportionate impact and left a lasting impression on those who witnessed or heard about them.Footnote 12 The focus of Redlich's inquiry, after all, was not the woman's suicide, but the trauma of the soldier who witnessed it.

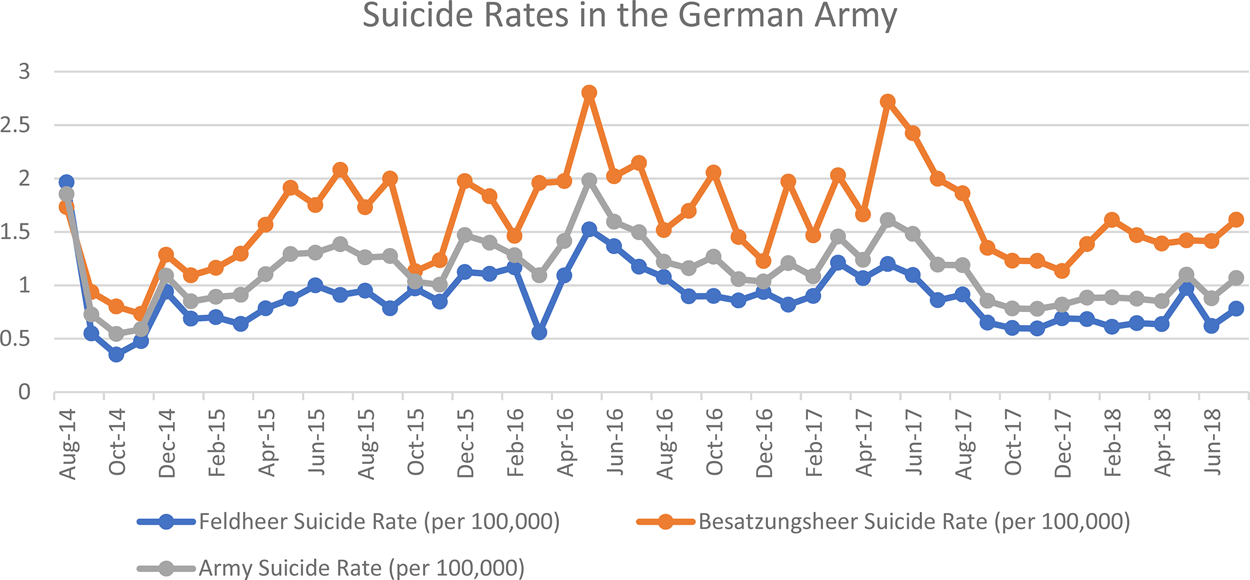

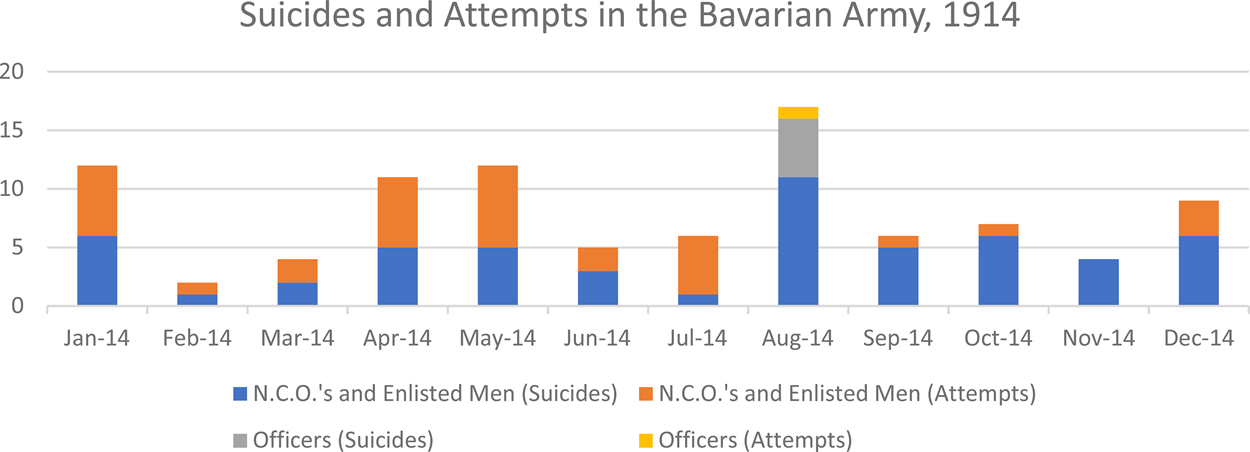

Indeed, the fact that the quantitative peak of explicit wartime male suicides correlated with the shift from peace to war—and therefore also with a mass influx of men into the army and soldiers to the front—suggests that this gendered dimension dovetailed with the soldier-civilian distinction and put military men at the forefront of this continuum. Most notably, calculated using the data from the official Medical Report on the German Army (Sanitätsbericht über das Deutsche Heer), widely considered the most reliable source for German casualty figures by historians, the wartime suicide rate in the German army actually began at its penultimate height in August 1914, being surpassed only once, in May 1916 (Figure 3).Footnote 13 Further, this was the only month where the suicide rate was higher for the Field Army (Feldheer)—the part of the army that engaged in combat operations—than the Replacement Army (Besatzungsheer). An examination of the figures for the Bavarian army, which made up roughly 10 percent of the total German army and is the only one for which data have survived for the entirety of 1914, reinforces this quantitative picture of the shift from peace to war being particularly traumatic for men in uniform, as August marked the clear peak for that year (Figure 4). Taken together, these figures point toward the war's outbreak itself being the main proximate cause for male suicides and suggest that the initial combat engagements—or fear of them—were something of an “original” moment of anguish for men in the rapidly expanding German army.

Figure 3 (Data Source: Der Heeres-Sanitätsinspektion des Reichswehrministeriums, ed., Sanitätsbericht über das Deutsche Heer (Deutsches Feld- und Besatzungsheer) im Weltkriege 1914/1918. Vol. III. Die Krankenbewgung bei dem Deutschen Feld- und Besatzungsheer im Weltkriege 1914/1918 (Berlin: E. S. Mittler & Sohn, 1934): Denominator: 5*-8*; Numerator: 133*-137*):

Figure 4 (Data Source: Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Abt. IV Kriegsarchiv, Kriegsministerium 10916 “Verzeichnis über Selbstentleibungen im K. B. Heere für das Jahr 1914.”)

This anguish was clear on the ground. On August 5, 1914, a twenty-eight-year-old Lance Corporal (Gefreiter) in the Württemberger 123rd Reserve Infantry Regiment hanged himself “in his bride's house.” According to the statistical compendium of wartime suicides in the Württemberger Army Corps—the only place where record of this suicide survives—the reason for the suicide was the “cancellation of the engagement by his bride.”Footnote 14 The timing, however, suggests that a moment of personal crisis (the canceled engagement) occurred simultaneously with a moment of national crisis (the outbreak of, and mobilization for, war). The Lance Corporal had already done his mandatory two years of military service and recently become a Landwehrmann Class I, which comprised reservists between the ages of twenty-eight and thirty-two.Footnote 15 His suicide thus occurred less than a week after he likely received his mobilization order, which in turn would have meant a rapid and total social dislocation regardless of what happened with his engagement. In some cases, German reservists had only twenty-four hours to set their home affairs in order after being called up; at most they had a few days.Footnote 16 Thus, though it seems incontestable from the surviving information about this suicide that the immediate catalyst was personal, the simultaneity of intersecting crises points toward the onset of war as an inextricable contextual element creating a deeper backdrop of uncertainty and socio-emotional displacement sitting behind that catalyst.

In many cases the connections were more direct. The body of a drowned soldier was pulled from the Danube on August 28, 1914, after having been in the river for roughly three weeks. The military court of the Württemberger 54th Infantry Brigade conducted a series of investigations over the course of the next month, which indicated that the dead soldier was a cavalryman, an Uhlan, who had been prosecuted for desertion (Fahnenflucht) by the court of the 27th Infantry Division on August 22.Footnote 17 A follow-up report from February 1915 concluded that the soldier in question was “reported to be a strange person [ein einenartiger (sic) Mensch], one who sought death in the Danube because he absolutely did not want to be a soldier,” though the author did admit that the case “could also be treated as an accident, given that there is no evidence of any third person being involved in the death.”Footnote 18 Despite that uncertainty, the death was classified as a suicide, with the earlier conclusion recorded as the reason for the suicide by the Württemberger War Ministry, using nearly identical language: “A strange person in civilian life [Im Zivilleben eigenartiger Mensch] who absolutely did not want to be a soldier.”Footnote 19

Given that this death likely occurred in the first week of August, it appears this man found the prospect of being a soldier so overwhelmingly negative that he opted to take his own life rather than ever report for duty. This is less surprising when one considers that the Uhlan was in a Field Army unit—he was, in fact, the only recorded suicide in the Württemberger Feldheer in August 1914—and thus was likely to be sent to the front more or less immediately. His desertion and probable suicide thus appear as the result of an implicit recognition and fear of what he would likely have faced there, though this is only suggested, not definite. It is unclear what exactly was considered “strange” about the man, as well as why the authors of the various reports were so sure the reason for his suicide was that “he absolutely did not want to be a soldier.” But when read together with the repeated comments about the soldier's idiosyncrasy, his desertion and death ultimately proved to be an early case of the conceptual and moral pathologizing of an “unwillingness to sacrifice” that came to play a dominant role in German psychiatry during the war.Footnote 20 What could a man who would prefer to die in the Danube rather than face possible death and mutilation in combat be other than “strange”?

A qualitative analysis of the information provided in the Bavarian army's statistical index of suicides further reinforces this picture. For example, a twenty-eight-year-old military cook shot himself on August 5, 1914, apparently due to “overstrain in service [Überanstreng. im Dienst]” and “overwrought nerves [überreizte Nerven].”Footnote 21 That same evening, a twenty-seven-year-old reserve infantryman hanged himself in Regensburg, purportedly a result of his “fear of the war [Angst vor d. Kriege].”Footnote 22 Five days later, on August 10, a thirty-six-year-old reserve artilleryman hanged himself, allegedly because he “did not want to be moved to the front [Wollte nicht mit ins Feld abrücken].”Footnote 23 In cases such as these, the Bavarian War Ministry considered the specific causes of its soldiers’ suicides to be clear enough to record their explicit connections with fears and concerns relating to the newly begun war, creating an inadvertent portrait of the anxiety and suffering Germany's decision for war engendered in the process.

These kinds of anxieties were not unique to the lower ranks. Ironically, it appears to have been among officers, who disproportionately came from the social groups most enthusiastic about the war's outbreak, that an explicit and enduring inclination toward suicide emerged most prominently right at the start of the war.Footnote 24 Indeed, German military doctors reported a linkage among suicide, self-injury, and a feeling of duty, most prominent among officers. Prof. Dr. Gustav Aschaffenburg, writing in the Handbook of Medical Experiences in the World War, contended that a “strongly developed feeling of duty [stark entwickelte Pflichtgefühl]” helped soldiers to overcome their depression and potential for suicide. However, he considered suicidal thoughts “understandable,” especially among those “at the head of a unit” who were under enormous pressure. In his view, the less duty-conscious (Pflichtbewußte) were more likely to seek escape from the front through “a harmless wound” or “mild illness,” not through suicide.Footnote 25 The authors of the Sanitätsbericht reached a similar conclusion, stating that “one can see a greater inclination toward suicide [Selbstmordneigung] among these ranks [officers, medical officers, officials, and especially veterinary officers] compared with NCOs and common soldiers [Mannschaften].”Footnote 26

Further examination of the Bavarian data suggests the plausibility of those conclusions. The official history Bavaria in the Great War provides figures for the numbers of both officers and enlisted men in the Bavarian Field Army at three points during the war—August 20, 1914; October 1, 1915; and September 1, 1917—where officers represented 2.86 percent, 2.52 percent, and 3.19 percent of the total, respectively, resulting in an average proportion of 2.9 percent.Footnote 27 As a proportion of total suicide attempts, however—that is, both completed suicides and “unsuccessful” attempts combined—officers accounted for 6.26 percent of the total. Looking solely at completed suicides, the figures are even starker: officers accounted for 8.94 percent of wartime deaths by suicide.Footnote 28 Despite how necessarily imprecise such estimates must be given the lack of numbers on the Bavarian Besatzungsheer and the small sample size, the surviving data suggest that officers both attempted and completed suicide in disproportionate numbers. And that greater inclination toward suicide began right at the start of the war: all of the recorded suicides and attempts of Bavarian officers in 1914—five suicides, one attempt—occurred between August 4 and 20.Footnote 29 Officers thus accounted for more than 35 percent of suicide attempts and over 31 percent of completed suicides in the Bavarian army during the war's opening month. As was the case with NCOs and enlisted men, these officer suicides resulted primarily from the war's outbreak itself. The very first—that of a thirty-two-year-old first lieutenant (Oberleutnant) who shot himself on August 4—is especially telling. The statistical index lists the reason for his suicide as “mental overstrain due to the mobilization and preparation for the War Academy [geistige Überanstrengung infolge d. Mobilmachung u. Vorbereitung zur Kriegsakademie].”Footnote 30

Taken together, these explicit suicides of 1914 can be thought of as a pessimist shadow vanguard, with military officers at the head: a behavioral “canary in the coalmine” that highlighted the state's essential role in conditioning the self-destruction of its citizens, and specific tensions and dislocations that would persist and compound over the next four years. The cheering crowds so famously immortalized in the photographs from that summer thus found their inverted corollary in the now-fragmented reports of soldiers dead by their own hands.

Implicit Self-Destruction: War Volunteers and the Combat Death Rates of 1914

Right from the beginning, however, those suicides were dwarfed by the mass of combat deaths during the war's opening months. While the Sanitätsbericht officially recorded fifty-four suicides in the German army during August 1914, that same month saw 18,662 men killed on the western front alone.Footnote 31 Indeed, as multiple historians have noted, the Germany army recorded its highest death rates during the first three months of the war.Footnote 32 Not even during the “great battles” of 1916, nor during the final offensives in 1918, did the death rates match those at the start (Figure 5).

Figure 5 (Data Source: Sanitätsbericht III, denominator: 5*-8*; numerator: 140*-143*)

It is therefore all the more striking that August 1914 was also the quantitative high point for war volunteers. Between 185,000 and 250,000 Germans volunteered for the army that month, with more recent estimates falling on the higher end.Footnote 33 For comparison, Prussian units alone accepted 143,922 volunteers during just the first ten days of August, while the French received only 40,000 volunteers in the war's first five months.Footnote 34 Indeed, following Alexander Watson's estimates, fully half of the roughly 500,000 Germans who volunteered for military service from 1914 to 1918 did so in the war's opening month.Footnote 35 And while the majority of volunteers came from what could be considered the “urban middle class,” and the educated and the elite were massively overrepresented compared with their share of the German population as a whole, the volunteers were far more sociologically diverse than has long been assumed in the historiography.Footnote 36

Nor did they volunteer in ignorance of what this particular war meant for their chances of survival. The German government published the first casualty lists on August 9 and continued to do so roughly every three days for the duration of the war. In August 1914, the full lists were published in the newspapers, but they were so long that the government forbid their full publication that September. The state still allowed lists of the local dead, wounded, and missing to be published in the newspapers of smaller cities and towns, however, and the full lists continued to be posted outside the War Academy in Berlin throughout the war.Footnote 37

Thus, when the war was at its deadliest and—most importantly—when knowledge about that lethality was widely and readily available, German men from a variety of backgrounds volunteered to serve in their greatest numbers. Indeed, it appears that well over half of all war volunteers joined after the publication of the first casualty lists. Although complete figures for volunteering in the German army have not survived, a monthly breakdown for volunteering in Württemberg—a state that accounted for roughly 4.66 percent of volunteers in the war's opening month—has.Footnote 38 Württemberg recorded a total of 18,194 volunteers from 1914 to 1918, with 8,619 joining in August 1914 and 2,204 joining the following month.Footnote 39 More than 12 percent of Württemberg's total volunteers, therefore, joined during September 1914—the month with the highest combat death rate of the entire war and a point at which the comprehensive casualty figures had been published in newspapers throughout the country for more than three weeks. Viewed in this light, many combat deaths were also self-destructive, though implicitly so. Thousands saw the casualty figures and read about “the sudden and unexpected death of a young, powerful officer or a tried-and-true military official,” but still rushed to join the fight.

The experiences of an anonymous war volunteer in the Prussian army illustrate the dynamics of this implicit self-destruction on the micro-level. His very first diary entry, from August 4, 1914, is short, but nonetheless revealing: “Today I received permission to volunteer for the war. It is my birthday. I am 18 years old.”Footnote 40 First, like so many others, he sought to join up when the war itself was less than a week old. His initial impulse to volunteer, then, came with the outbreak of the war, prior to the first publication of the casualty lists, but also weeks before the German government began advertising for recruits.Footnote 41 Second, his age reveals that he was likely one of the roughly 18,000 high school pupils who volunteered in August 1914, which in turn highlights the generational contour of the implicit inclination toward death more sharply.Footnote 42 The average age of the volunteers in the sample was just under twenty-one; more than 55 percent of volunteers were younger than twenty—the age at which men became eligible for the draft in peacetime; and 88 percent were younger than twenty-five.Footnote 43 The author of the diary was therefore quite typical in many ways, especially given that he came from a wider pool of potential volunteers that would have remained untouched by conscription until at least 1916.

Most importantly, he sought and received permission to volunteer—presumably from his parents, given his age—despite the fact that this was not an official requirement. Indeed, receiving permission from one's loved ones was an essential social component of volunteering. The artist Käthe Kollwitz actually interceded on behalf of her younger son, Peter—who died in Belgium on October 22, 1914—to convince her husband Karl to allow him to volunteer. She recounted the scene in her diary on August 10:

It was also on that day, in the evening, that Peter asks [sic] Karl to let him volunteer before the Landsturm [comprised of older reservists] is called up. Karl speaks against the idea with everything he can. I feel thankful that he fights for him like this, but I know it doesn't change anything. Karl: “The Fatherland doesn't need you yet, otherwise they would have called you up already.” Peter, quieter, but firm: “The Fatherland doesn't need my year of service yet, but I need it.” He always turns silently to me with a pleading look, begging me to speak for him. Finally, he says: “Mother, when you hugged me, you said: ‘Don't believe me to be a coward. We are ready.’ I stand up, Peter follows me. We stand at the door and give each other a hug and a kiss and I ask Karl on Peter's behalf. —This single hour. This sacrifice which he has carried me to, and to which we have carried Karl.Footnote 44

Already at this early date, both Kollwitz parents recognized what volunteering implicitly meant: the highly increased likelihood of Peter's self-aware death. As Käthe wrote on August 27: “I am afraid that this soaring of the spirit will be followed by the blackest despair and dejection. The task is to bear it not only during these few weeks, but for a long time—in dreary November as well, and also when spring comes again, in March, the month of young men who wanted to live and are dead. That will be much harder.”Footnote 45 Indeed, the entire conversation Kollwitz recounted occurred the day after the first casualty lists were published, and thus at a point when there could be no doubt about the lethality of the new war.

Even once a man had secured the assent of his loved ones, however, that did not mean he was able to volunteer right away, as the case of the anonymous Kriegsfreiwilliger illustrates. For while this young man received permission to volunteer on August 4, he wasn't actually accepted into the army until ten days later—notably, after the publication of the first casualty lists—when the Ersatz-Battalion of the 31st Infantry Regiment in Altona declared him fit and took him on his third attempt to join them.Footnote 46 He was initially rejected by the 31st on August 5, after which he attempted to register with the 9th Jäger Battalion later the same day, but was also rejected. Indeed, he was one of many potential volunteers chasing rumors of which units might be recruiting in the first weeks of the war. As he wrote on August 8: “Left at 12:35. Many war volunteers on the train who had also heard that the 85th was still recruiting. Rejected. Went back to Hamburg at 2:25.”Footnote 47 According to his diary, it took six attempts with four different units until he was able to join the army.Footnote 48 This was not atypical. The Kriegsfreiwilliger Paul Wittenburg, for example, similarly recounted deciding to join on the first day of the mobilization, but being unable to find a unit to take him until two weeks later, when he was admitted into a field artillery regiment.Footnote 49 Because most units filled their manpower needs through conscription, many volunteers had to exert considerable effort to join up, often visiting six or seven depots before they found a unit willing to take them.Footnote 50 Behaviorally, then, the war volunteers of August 1914 appear even more strongly inclined toward death than their numbers alone would suggest: many expended substantial energy to be accepted into a unit and conduct the deadly work of the state.

Finally, because all volunteers had to apply to specific units, volunteering could, ironically, provide an opportunity to shield oneself somewhat from the risks of combat depending on which unit one joined. As Benjamin Ziemann notes, the sociologist Norbert Elias, who was also eighteen years old when he joined the army in 1915, “owed his survival in the First World War to his family's (correct) advice that volunteering for a radio unit would spare him from dangerous operations on the front line.”Footnote 51 What is most striking, however, is that it appears many volunteers went in the opposite direction. In Württemberg, only 3.83 percent volunteered for the pioneers, who chiefly performed engineering and construction tasks, while 41.33 percent volunteered for the infantry.Footnote 52 Of course, these figures also reflected the manpower needs of the army itself, which dictated the various units’ demand for volunteers. But they nonetheless suggest the general rarity of a case like Elias's and the degree to which many war volunteers inclined their behavior toward death on the individual level not just in a general sense through joining the army, but by specifically joining units that would soon face combat.

And in at least some cases, volunteers’ self-destruction and its conditioning by the state became much more explicit. On November 7, 1914, a twenty-year-old Kriegsfreiwilliger in the Saxon army, who had joined on August 28, attempted suicide by shooting himself in the chest. The surviving report on the case stated simply: “Appears to be a suicide attempt. Reason: probably fear of punishment. Nothing of this case is yet known to the public.”Footnote 53 Although no statistics on the number or rate of volunteer suicides have survived, cases like this highlight how swiftly and lethally disillusionment could set in, even in the war's early months. It is unclear what this volunteer may have been facing punishment for or if he was actually facing punishment at all. As Andrew Bonnell notes, “fear of punishment” was listed so often as a reason for military suicides prior to the war that many critics believed it to be a cover for abuses within the army that resulted in soldiers killing themselves.Footnote 54 Moreover, war volunteers were treated so badly by their superiors at the start of the war that the Prussian War Ministry actually issued a decree on August 22, 1914, reprimanding officers for it.Footnote 55 Finally, it is noteworthy that the report explicitly mentions that there was no public knowledge of the case, an indication that first, the Saxon War Ministry was concerned to at least some degree about public awareness of soldiers’ suicides; and second, that there were likely other cases that the public did eventually become aware of. Indeed, at least one similar case apparently did make it. On January 12, 1915, a war volunteer was found hanged in a probable suicide. The report on his death specified that the case “should already be mentioned in the press this evening.”Footnote 56

Ultimately, then, the spectrum of implicit self-destruction ranged from those who reluctantly obeyed the state's call to arms and then did their best to ensure their survival when given quotidian opportunities to do so to those who actively volunteered not only for military service, but for service in combat units, despite widespread publicity of the massive losses suffered by German troops. It was not that masses of Germans suddenly developed a death wish in August 1914. Rather, what is most striking is that so many of them—in varying ways and to varying degrees—acted as though they did.

Personal Self-Destruction as National Sacrifice

Contemporaries in 1914 did not view their actions in those terms, however, especially when it came to volunteering and death in combat. Rather, like the Kollwitzes, most conceived of these actions as sacrificial: a necessary “giving something up”—most pertinently here, one's life or the life of a loved one—for a “higher good,” which morally and socio-emotionally “transformed” that self-destruction.Footnote 57 The self-destructive elements of the thanatological constellation that crystallized in 1914 remained an undercurrent—buried and flowing beneath the “spirit of 1914,” though both were part of the same oceanic system.

One can see this configuration in the short war experience of Franz Blumenfeld, a twenty-three-year-old law student who volunteered at the beginning of August 1914 and was killed that December. On September 24, on the train heading to the front, he wrote a farewell letter to his mother that outlined the linkages between sacrifice and the newly emerged inclination toward death:

I find that war is a very, very evil thing, and I also believe that if diplomacy had been more skillful, it could have been avoided this time too. But, now that it has been declared, I find it self-evident [selbstverständlich] that one should feel oneself so much a member of the nation that one must bind one's fate as closely as possible with that of the whole. And even if I were convinced that I could do more for my Fatherland and its people in peace than in war, I should think it just as perverse and impossible to let such deliberate, almost calculating considerations weigh with me now as it would be for a man going to help somebody who was drowning, to stop to consider who the drowning man was and whether his own life was not perhaps the more valuable of the two. For what is decisive is always the readiness to make a sacrifice [Opferbereitschaft], not the object for which the sacrifice is made.

From all that I have heard, I find this war to be something awful, inhuman, mad, obsolete, and in every way depraving, that I have firmly resolved, if I do come back, to do everything in my power to prevent such a thing from ever happening again in the future.Footnote 58

Although oriented toward pacifism and life, through volunteering, Blumenfeld nonetheless inclined himself toward war and death. His letter makes the moral element linking orientation and inclination—and thus current and undercurrent—overt: “the readiness to make a sacrifice.” What is most striking, however, is not just that sacrifice provided the socio-moral, emotional, and conceptual link between the two, but the specific way in which he conceived of that linkage.

First, Blumenfeld almost completely divorced jus ad bellum (justice of the war) from jus in bello (justice in the war).Footnote 59 The divorce was so complete, in fact, that the letter suggests he actually considered the conflict unjust to at least some degree. Nonetheless, he clearly saw acting justly as requiring his military service; a sacrifice not only of his life, as it played out in the event, but of his ideals as well, at least in a behavioral sense. Second, in volunteering for the army, he explicitly subsumed himself within the larger national collective. Through reconceiving of his own personal sacrifice in national terms, he was able to resolve the ideational contradiction between his action and not only his ideals, but his moral analysis of the war itself.

On a deeper level, Blumenfeld's letter indicates the way the sacrificial “spirit of 1914” was experienced in a more literal sense, which made it so powerfully resonant. The types of mental gymnastics displayed in the letter point toward his sense of duty, in this context, being first and foremost a moral feeling: an emotion that implied the need for and pointed toward a behavior inherently imbued with moral content. Indeed, “feeling” appears as the lynchpin of Blumenfeld's letter: his Pflichtgefühl was strong enough that it transcended his actual reasoning about the war. The “ideology of sacrifice”—that “diffuse body of values, concepts and themes extolling the righteousness of laying down one's life for a greater cause”Footnote 60—was the intellectual gloss on a primarily emotional process whose behavioral vector was socially directed and strongly conditioned by the state. It was, after all, the political and military leaders of the Kaiserreich who not only decided to enter the war, but whose decisions on how to conduct it created the specific physical, social, emotional, and moral dislocations that correspondence like Blumenfeld's attempted to bridge.

This sacrificial emotional-moral matrix was not unique to Blumenfeld. During the first year of the war, the Institute for Applied Psychology in Potsdam circulated a wide-ranging questionnaire among front soldiers, which formed the basis for Paul Plaut's 1920 “Psychography of the Warrior.” In the introduction, Plaut summarized the centrality of moral feelings to Germans’ responses to the outbreak of war: “No one had a conscious understanding of [the war], of what it really meant, surely no one; it was a suggestibility that everyone integrated together into a uniform mass of feelings [einer einheitlichen Gefühlsmasse], into a symphony, whose constant, recurring, and dominant theme was enthusiasm.”Footnote 61 Thus, although this complex of feelings may have been rhetorically coded as “war enthusiasm,” that phrase was largely a misnomer—merely the name given to the complicated and varied depth of emotion and intensity of feeling so characteristic of the war's opening weeks.

Indeed, the volunteers who responded to the survey recorded no “war enthusiasm” as such motivating their decisions. One interviewee reported that he had “little to no war enthusiasm, even though I fully approve of the war. I joined as a war volunteer out of a feeling of duty [Pflichtgefühl]. It was self-evident to me that I had to immediately join on the first day. This is partially caused by the nationalist attitude which was cultivated in my student association.”Footnote 62 Another succinctly reported the same motivation: “Never felt war enthusiasm. Joined out of a consciousness of duty [Pflichtbewusstsein].”Footnote 63 And at least one recorded a near-identical motivational matrix to Blumenfeld, complete with an expressly negative appraisal of the war and a multifaceted complex of moral feelings undergirding and directing his behavior:

Joined as a war volunteer on the first day. It was clear to me from the beginning that a modern war is an incomparable tragedy and a crime against humanity. Therefore, I cannot say I felt an actual war enthusiasm. But the mood [Stimmung] of the first days self-evidently directed me toward what I had to do. My love of the Fatherland had not been unrestricted until then, but now I perceived myself as a good patriot. Not only because Germany is my Fatherland and I must defend it, but rather because its culture is higher, despite some things, and because I know justice is on its side. Lust for adventure definitely made a strong impact within this mood of the first days. It awakened imprecise [unbestimmte] feelings of joy and honor of a romantic life at war, which, given the ideas in the cultured descriptions of war, had to appear attractive in the Sturm und Drang of youth. In the first place, my feeling of duty [Pflichtgefühl] was decisive. After that came a second motive: shame. Should I, as a young man, stay at home when not only older comrades but also Landwehr and Landsturm men were going into the field? I registered as a war volunteer on day one so that I would no longer have to wear civilian clothes. Courage had nothing to do with it.Footnote 64

Like Blumenfeld, this volunteer was explicit in his ethical condemnation of war. But he nevertheless joined on the first day, driven by the “mood” of the moment, which made the proper action to take “self-evident.” A number of more specific ideas and tropes guided and directed this mood, most notably a “lust for adventure” rooted in literary representations of war, evidenced most clearly in his use of “Sturm und Drang.” However, as the volunteer went on to explain, what that “lust for adventure” meant in practice was “imprecise feelings of joy and honor,” with imprecise being the operative word. In that sense, “lust for adventure” was similar to “war enthusiasm” in that, in practice, it encompassed a wide range of behaviors, motivations, and feelings within a single term. Ultimately, as he went on to state, it was his feeling of duty—a feeling with a clearer direction—that he considered decisive.

Moreover, his testimonial makes clear that the sacrificial matrix of moral feelings was not composed entirely of ethically positive elements, but contained powerful negative motivators as well. In his description, shame appears as the shadow of a feeling of duty, but one which still inclined toward the same behavior. It wasn't just that this volunteer felt that joining the army was the right thing to do. He felt that not joining, especially when so many other, older men were going off to fight, would not only be the wrong thing to do, but would be recognized by others as an immoral action. Wearing civilian clothes as a young man in a time of war was akin to announcing oneself as unethical and unmasculine, which was a recognition this volunteer—and many other German men, including Peter Kollwitz—clearly could not abide.Footnote 65 The subtext of his final statement that “courage had nothing to do with it” suggests that the opposite was in fact the case: fear of being viewed as cowardly acted as stick to his Pflichtgefühl's carrot.

Moral feelings came first, justifications second. The interviewee's response is riddled with contradictions, but the depth of emotion and its behavioral direction provided a unifying thread. Like Blumenfeld, this young man felt a very clear sense of what he had to do once war was declared—namely, volunteer for the army—but only constructed and improvised the ideational justifications for that action post hoc, once asked by the institute's researchers.Footnote 66 The fact that he made explicit reference to his education via literary allusions, as did the other volunteer who mentioned the cultivation of nationalist views in his student fraternity, in turn points to these institutions as primary providers of the “raw material” out of which he—and others—improvised that justification. Just as the “enthusiastic” crowds of late July and early August “drew upon the repertoire of conventions associated with patriotic display, with student marching, or with the public festival,”Footnote 67 so these new soldiers drew on the types of moral and ideational justifications their education had cultivated prior to the war to explain, in ethical terms, their more spontaneous emotional decisions to volunteer. In the event, however, these constituent elements—moral feelings, post hoc rationalizations, and actual self-destructive behaviors—were inextricable from one another: all were part of a common thanatological constellation.

Thus, the emotional mass Plaut described was morally centered on the need for sacrifice, which was, in his view, the true essence of the war:

Because it cannot be said enough: this war was more than a movement of weapons. The experience of it was not only anchored in soldiers who defended or attacked with rifles and hand grenades. It was a path to general sacrifice [ein allgemeiner Opfergang] which the entire people, indeed the entire cultural world had to line up for. All had to experience the war itself, which—some more, some less—left none untouched. And yet the soldier and his experiences still stand at the foreground of interest, because he has experienced the war in its most elemental and most distinctly original [ureigensten] sense.Footnote 68

In Plaut's analysis, war volunteers made up a sacrificial vanguard as those who experienced the war in its primal sense. But as such, they were merely at the front of a mass sacrificial movement: everyone would have to walk to the altar and make an offering, even if some would ultimately give more than others. The unity of the war was thus the unity of communal sacrifice, but one with mass death at its foundation: that “most elemental” and “distinctly original” meaning of war. When the war was less than a month old and when, therefore, most would have had little to no time to process its significance or consequences, sacrifice was a readily available moral concept many reached for to impose a positive meaning on those consequences and give order to the chaotic and conflicting feelings of that August.

Whether dealing with potential or actual death, suicide or death in combat, sacrifice and its related concepts—particularly duty, honor, and shame—were emotionally resonant moral ideas that “transformed” acts of personal self-destruction into acts of national sacrifice. In essence, sacrifice was the name given to socio-morally and emotionally acceptable—and, more often, laudable—suicidal behaviors. Millions of Germans resigned themselves to or otherwise accepted the new suicidal substrate by conceiving of it in sacrificial terms.

The Suicide of Major General von Bülow: A Thanatological Microcosm

No single example distills this multifaceted thanatological constellation and the moment of its emergence more fully than the suicide of Major General Carl-Ulrich von Bülow, a younger brother of the former Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, on the night of August 6, 1914. A career soldier, Bülow was fifty-one years old when the war began and he assumed command of the 9th Calvary Division on August 1, 1914.Footnote 69 On the night of August 5, the division participated in the initial attack on Liège, but the assault failed and the Germans suffered heavy losses, developments which sparked an intense depression in the major general. According to his First General Staff Officer, Fritz von Herwarth, that evening, the division “was attacked by francs-tireurs, which resulted in quite unpleasant fighting and, especially on the morning of 6 August, to reprisals, wherein a considerable number of death sentences had to be pronounced.” After informing his brigade and regimental commanders of the situation and, at Herwarth's insistence, announcing “the firm decision that he was determined to continue to carry out the ordered task with the division,” Bülow disappeared. His body was discovered by two artillerymen, who informed Herwarth later that evening:

I found von Bülow lying on his cloak in a shallow ditch with a pistol in his hand and could have no doubt that it was a suicide.… My adjutants and orderlies came to the same conclusion and carried out the provisional burial [vorläufige Beerdigung] with me. Other people, enlisted men or the like, did not see the dead man. At 4:00 am the next morning I made it known through a divisional order that Major General von Bülow had been found shot the previous evening [am Abend vorher erschossen aufgefunden worden sei].Footnote 70

First, in Herwarth's recounting, Bülow appears as an archetypal example of the inclination toward suicide among officers noted in the Sanitätsbericht and explained by Handbook of Medical Experiences. Moltke's war plan required that Liège be attacked no later than the third day of the mobilization, lest it delay the German advance.Footnote 71 The failure of the initial attack in which the 9th Cavalry Division participated, therefore, was not a minor setback, but one that threatened to derail the entire German war plan. He thus appeared to be one of the unit commanders for whom the Handbook's authors considered suicide “understandable”: “We can only guess, not measure, how much heroic courage [Heldenmut] it takes to remain at the head of a unit under such conditions. But one can understand that occasionally suicide appears as the only way out, the only way to put an end to the ordeal.”Footnote 72 Given that the reports of the attack's failure sparked Bülow's depression, it seems likely that the pressure of the situation was one of the proximate factors leading to his suicide.

When one considers that Moltke himself suffered a nervous breakdown after being stopped at the Marne, one gets a clearer sense of the kinds of intense mental pressure German commanders were under more generally.Footnote 73 Much of this was of course self-imposed, given the tight timetable they had set for themselves in keeping with the German military's understanding and practice of the “cult of the offensive” and the institutional preference for “victories of annihilation” (Vernichtungssiege).Footnote 74 Nonetheless, what was most significant was the way many German commanders experienced defeat not only as a military failure, but a personal one as well. Moltke, somewhat uniquely at the time, emphasized independent leadership and individual initiative on the part of his commanders.Footnote 75 Individual commanders’ decisions could therefore turn the tide one way or the other, increasing the pressure on decision-makers down the chain of command. In this sense, Bülow represented an even more extreme end of the shadow vanguard: suicidal shame as the emotional correlate of military defeat.Footnote 76

Second, Herwarth's repeated mentions of attacks by francs-tireurs highlight a specific moral tension at work as well, one intimately linked with the self-imposed pressure on the military leadership for rapid victory in 1914. As the most easterly Belgian province, Liège was strategically key to the German invasion and had to fall in order to “force the gate to Belgium.”Footnote 77 When the Germans encountered unexpectedly strong resistance once the invasion began, they immediately blamed the setback on civilian irregular fighters—francs-tireurs—primed by inculcated historical memories of 1870.Footnote 78 In a massive case of auto-suggestion, the German army murdered 5,521 Belgian civilians in the course of the invasion, driven by a collective delusion that they faced a franc-tireur war.Footnote 79

Although he did not live to see the full extent of these atrocities, Bülow was present at the very beginning of this murderous rampage. Mass executions of Belgian civilians began in Liège on August 5, with at least 850 civilians killed and approximately 1,300 buildings burned down within three days.Footnote 80 Although it is unclear whether the 9th Cavalry Division actively participated in the first wave of “reprisal” killings or was merely present as they were carried out, their commander apparently could not live with what his army had done.Footnote 81 His suicide not only embodied the more capacious sense of socio-emotional dislocation, isolation, and confusion engendered by the Kaiserreich's decision for war, but also served as an implicit condemnation of the army's conduct:

Especially in the course of 6 August, [Bülow] continually spoke about the war in general and expressed his regret [Bedauern], if not disgust [Abscheu], that the war, which was to be welcomed by a soldier, had now begun with an invasion of a neutral and peaceful land. I would like to believe that this thought, in connection with the difficult francs-tireur battles at the time, heavily depressed the mind of Herr von Bülow and led him to this step.Footnote 82

In Herwarth's estimation, then, Bülow was like many other German soldiers, who, suddenly cut off from their long-standing ties and networks, found themselves adrift not just socially, but also ethically. As Marc Bloch noted in 1921: “The German soldier who … marches into Belgium has just been brusquely removed from his fields, his workshop, his family…. From this sudden dislocation, this unexpected severing of essential social ties, there arises a great moral confusion.”Footnote 83 Indeed, although Bülow was a career soldier, he was in many ways just as cut off from these foundational relationships as enlisted men: he took command of his unit only five days before his suicide.

Further, according to Herwarth, it was the disconnect and dissonance between Bülow's normative vision of war and the German army's actual practice of it that was the primary cause of his suicide. But here, the great moral confusion arose not from suddenly having gone from civilian to soldier, but from having to conduct the war in a way that did not accord with Bülow's sense of military ethics. Given the centrality of the debate over the 1914 atrocities to not only the larger meaning of the war while it was raging, but also to the shape of the peace settlements and the memories of the war that solidified in the first postwar period, Bülow's suicide was a harbinger of the deep stakes of the conflict: the destruction of both lives and morals in a war Germany's leaders had decided to enter.Footnote 84

Finally, as with so many others, Bülow's death was immediately framed in explicitly sacrificial terms, evidenced in the numerous condolence letters and telegrams sent to his brother, Bernhard, after his death.Footnote 85 Helene Lebber, a friend of former the chancellor, wrote him a letter on August 9 expressing her hope that “God will comfort you and help you bear his sacrifice.”Footnote 86 Both the king of Bavaria and the Nobel Prize–winning author Gerhart Hauptmann sent telegrams on August 12 that explicitly referred to the major general's “hero's death [Heldentod].”Footnote 87 But the most explicit came from Walter Rathenau, who not only went on to found the War Raw Materials Department later that month, but became one of the loudest public voices calling for a levée en masse in October 1918, well past the point when the war was definitively lost—functionally, a suicidal “final battle” (Endkampf).Footnote 88 On August 9, he wrote in a telegram to Bernhard that his pain could be “mitigated by the knowledge that your highly esteemed brother sacrificed his life for the protection of the country.”Footnote 89

This single case thus contains all of the major elements of the inclination toward death that emerged in 1914: a thanatological microcosm. Bülow's suicide itself indexed the intensity of the social, emotional, and moral distress engendered by the war's onset, but was immediately and literally buried, by all surviving indications being recorded as simply one of the thousands of combat deaths of the war's opening month. Buried along with it, therefore, was the major general's implicit condemnation of the army's conduct in Belgium, as well as the more capacious sense of socio-emotional dislocation, isolation, and confusion his suicide embodied. The potential signal of the full stakes of the war—moral, social, emotional, mortal—went with Carl-Ulrich himself into his provisional grave. Finally, his death was immediately coded as sacrificial, which imbued it with a positive moral and emotional meaning and created a cathartic narrative for those left behind. Ironically, that cathartic narrative pointed in the exact opposite direction as his suicide itself: toward continuation of the conflict until the sacrifices of “the fallen” were vindicated through victory.

The Suicidal “Spirit of 1914”

In a 1915 essay titled “On the Experience of War,” Siegfried Kracauer argued that it was “impossible to check the actual position of each individual person” as the “kinds of true love of the Fatherland in others, now triggered by the war, are infinitely diverse and individual.” There was a struggle for emotional supremacy between “the feeling of duty, the joy of being in harmony with the community, being dully pulled along by the mood of the masses, the appetite for adventure, the desire to strike, the ambition, the curiosity.” Ultimately, in Kracauer's estimation, “the feeling for the Fatherland mostly serves as an unconscious disguise.”Footnote 90 He was more correct than he knew. Not only did the “feeling for the Fatherland” serve as an unconscious mask for an entire complex of often contradictory emotions sparked by the war's onset. But that complex itself was concealing something even more profound: a self-destructive thanatological constellation—a new inclination toward death.

This constellation had three principal layers. The first and base layer consisted of suicides themselves: acts and instances of self-destruction recorded as such by contemporaries. Though a definite minority, these suicides functionally formed a collective shadow vanguard that indexed the profound consequences of the mass shattering of socio-emotional ties and moral certainties engendered by the German state's decisions for and in the newly begun war. The second layer consisted of implicitly self-destructive behaviors—oriented toward life but inclined toward death—most directly embodied in war volunteers. Together, these two layers formed the self-destructive undercurrent that was, in practice, what so many millions of people endured over the next four and a half years. The third and final layer—the surface current—papered over the self-destructiveness of the entire enterprise by encoding it within the “feeling for the Fatherland,” the “spirit of 1914,” and its call—indeed demand—for sacrifice. But that “spirit” was one that must be understood more literally: something intangible, yet powerful, equally “sacred” and imprecise. It was less about “ideology” and more the name for a set of moral feelings that were acceptable to—and accepted by—a broad swath of the German public. The “spirit of 1914” had both a clear behavioral direction and an ethical valence that disguised the self-destructive undercurrent, though at least some, like the Kollwitz parents, caught a glimpse of its translucent shimmer.

Resch thus spoke prematurely when he concluded his lecture on a positive note by telling his fellow military doctors that they “need not look too blackly at the number of mental illnesses in the current war” because, after all, the psychiatric clinic in Strasbourg had only one-third of its 280 beds reserved for the “nervous” occupied at that moment.Footnote 91 The scale and ultimate impact of those affected by the triad of suicides, combat deaths, and the broader emotional distress at the war's mortal consequences was much greater than a quantitative analysis of wartime mental illnesses could show. The unity of purpose embodied in the crowds of August 1914 did indeed herald the durability of Germans’ support for the war and a willingness to sacrifice for the nation that outlived the euphoria of that summer and far outpaced psychiatric hospitalizations. But the suicides of their fellow citizens occurring simultaneously in train stations and family apartments, lover's homes and military encampments, highlighted something much darker and even more enduring: key socio-emotional vectors for the destruction of the Kaiserreich and its permanent disappearance from the political map.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, Kathleen Canning, Geoff Eley, and Cheyenne Pettit for their helpful comments and detailed feedback on this article. I would also like to thank the participants of the German Historical Institute's 26th Transatlantic Doctoral Seminar in German History and the commenter, moderator, and my fellow panelists at the 45th Annual German Studies Association Conference, all of whom provided critical feedback on earlier versions of this piece and helped shape it at a critical stage. Finally, I would like to thank the German American Exchange Service (DAAD), Central European History Society, and both the Rackham Graduate School and Eisenberg Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Michigan, all of whom provided funding that made the research for this article possible.

Matthew Hershey is a PhD candidate in the History Department at the University of Michigan. His current research explores the relations among suicide, sacrifice, and total war in Germany from 1914 to 1918. His work situates the history of wartime suicide within the broader context of Germans’ dynamic socio-cultural, moral, and emotional attitudes toward and experiences with death, violence, and killing.