In July 1994, historian Donna J. Guy published a methodological reflection on Latin American gender history in The Americas. This marked the journal’s first contribution of a series aimed at conveying the remarks of the Conference of Latin American History (CLAH)’s annual speaker. The invitation of Guy, a historian specializing in women and gender studies, as the annual speaker at CLAH in January 1994 was not accidental. It revealed the growing interest among Latin American academic communities in the field of gender history and the possibilities it offered to set new directions to Latin American history. According to Guy, by 1994, things were changing for gender historians. In the 1970s, when she first became interested in gender history, women and gender studies were marginal within the discipline. However, by the 1990s, she could “appreciate how accepted gender studies [had] become for Latin American historians.”Footnote 1

The publication of Guy’s talk for CLAH in The Americas was also representative of the development of women and gender histories within the journal itself. Since its first issue in 1944, women have figured as social actors in the histories presented by Latin American historians in the journal. Yet, the understanding of the category of “women” as well as the methods, concepts, and approaches used to comprehend women’s roles and gender relationships have changed over time. The trajectory of the Americas reveals these changes, and the multiple discussions and questions grappled with by Latin American historians when addressing the question of gender in the historical field. Particularly, in her 1994 reflection, Guy highlighted a recurring question among Latin American historians that has also influenced The Americas’ academic production on gender and women’s histories: Are the gender theories from the United States and Western Europe suitable for understanding gender relationships in Latin America? “Which approach was best for Latin American historians?”Footnote 2

In 1983, historian Joan Scott published an essay on the development of the field of women’s history during the 1970s and early 1980s. According to Scott, at least in the United States, the 1970s marked a peak in the production of studies on women’s history. During this period, there was a significant increase in academic publications, forums, and journal issues on various topics related to women, such as women’s suffrage, reproduction, women and wars, and women workers. This growth in “the new knowledge of women” showed promise for continued expansion in the future.Footnote 3 Scott argues that, at that time, there was no unified set of methods or theories guiding the development of the field. Instead, historians of women were more concentrated on making “women a focus on inquiry, a subject of the story, an agent of the narrative.”Footnote 4 For Scott, unlike histories that situated men as the agents of history and historical change (his-stories), women’s histories (her-stories) aimed to center women’s experiences in analyzing historical processes. The her-stories of the 1970s and 1980s sought to make explicit and address the omission of women’s experiences and voices from the narratives on the major historical processes, while revisiting and reinterpreting the past from the perspective of women as historical agents. Instead of considering women as mere epiphenomena of history, her-stories aimed to restore agency to women by emphasizing their pivotal roles in enabling historical change and social processes in the past.

A few years after the publication of this essay on women’s history, in 1986, Scott published “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis” in the American Historical Review. Historians concur that this article signaled a significant shift in the field of women and gender histories. This 1986 essay opened new directions for research and proposed deep questions regarding the limitations of women’s history in historicizing and interrogating the category of “women.” Although her-stories played a crucial role in challenging the male-centered narratives of history, they also tended to overlook the historical and contextual nature of gender experiences by assuming a universal and unchanging essence that applies to all women throughout history.Footnote 5 As per Scott, shifting the focus from “women” to “gender” would provide opportunities to examine gender identities and experiences as historical constructs rooted within power systems that intersect and influence wider social, political, cultural, and economic processes at various points in history.Footnote 6

Latin American historians of women and gender were familiar with Scott’s call to expand the scope of analysis by integrating gender as an analytical perspective for Latin American history. For instance, Guy’s 1994 reflection for CLAH in The Americas mentioned the potentialities of a gender approach to study masculinities and the formation of a heterosexual ideology within Latin American states.Footnote 7 However, the uses and transitions from “women” to “gender” have not been linear or uniform within the field of Latin American history. In 2001, Sueann Caulfield argued that “gender analysis has not been as central a concern in the different national historiographies in Latin America.”Footnote 8 Similarly, Heidi Tinsman, in her 2008 article “A Paradigm of Our Own: Joan Scott in Latin American History,” highlighted the differences in the way gender was studied in US and Latin American scholarship. She noted that while US historians readily embraced Joan Scott’s ideas, feminist scholars in Latin America were dealing with a Cold War context where women were striving for recognition and inclusion in their social and political movements. This led to a situation where, in countries such as Chile, “women” was the primary focus of analysis rather than “gender.”Footnote 9

The academic output in The Americas provides crucial insight into the main discussions, categories, and approaches of Latin American women and gender histories. In line with Tinsman’s argument, tracing the development of the scholarship in The Americas sheds light on how Latin American historians have proposed gender-based frameworks and categories that extend beyond Scott’s ideas and highlight the inadequacies of US approaches when it comes to capturing the particularities of Latin American gendered realities. This essay will argue that, in line with Tinsman and Caulfield, the development of women and gender histories in the journal shows that “women”—rather than “gender”—has been the main focus of Latin American scholarship. Yet, the transition, or lack thereof, from “women” to “gender” does not necessarily indicate progress or backlash. Instead, in the academic production of The Americas, historians have critically examined the category of “women”. They have highlighted how the meanings and power dynamics associated with “women” and femininity vary across contexts and interact with class, ethnic, racial, and generational identities and social systems. Ultimately, in studying women and gender histories, scholars publishing in The Americas have questioned simplistic understandings of “women” as an unchanging essence and have rather critically examined the social origins of “women” and the power systems that have shaped this category in Latin American gendered societies. Furthermore, while the journal has primarily focused on “women,” gender analysis has also influenced the historiographical contributions of Latin American historians in The Americas. This is particularly evident in their examination of the connections between gender, class, and race in Latin American past societies.

This essay combines quantitative tools and text analysis methods with a qualitative approach to explore the evolution of academic research on women and gender histories in The Americas from Volume 1, Number 1 (July 1944), to Volume 81, Number 1 (January 2024). In total, throughout this period, The Americas published 88 articles on women and gender histories. A graph illustrating the number of publications over the years (Chart 1) helps us visualize three periods where the number of publications increased, and a decline from the mid-1960s until 1980, during which there were no publications on this subject in the journal.

Chart 1 Number of publications on women and gender histories in The Americas (July 1944–January 2024)

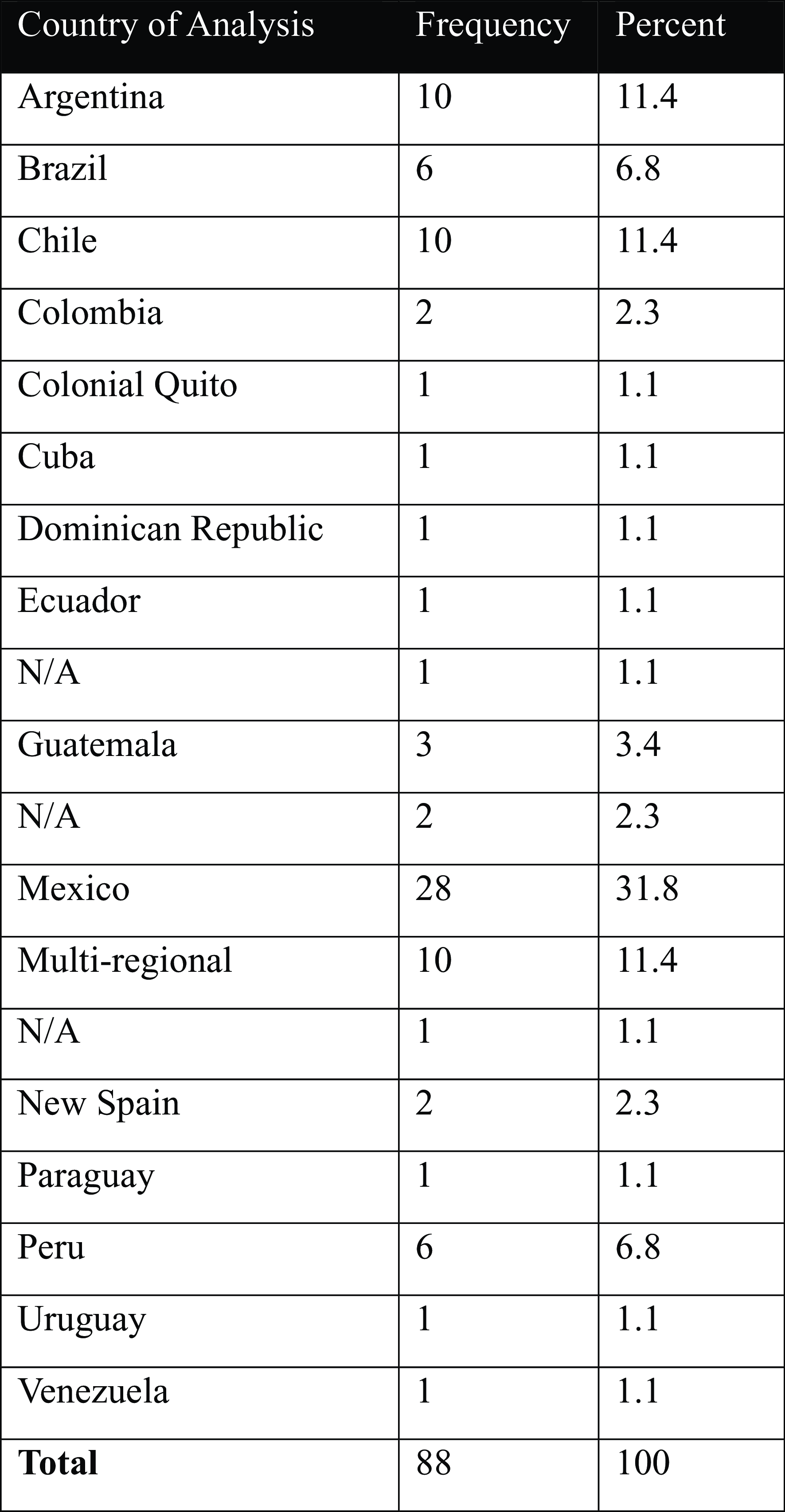

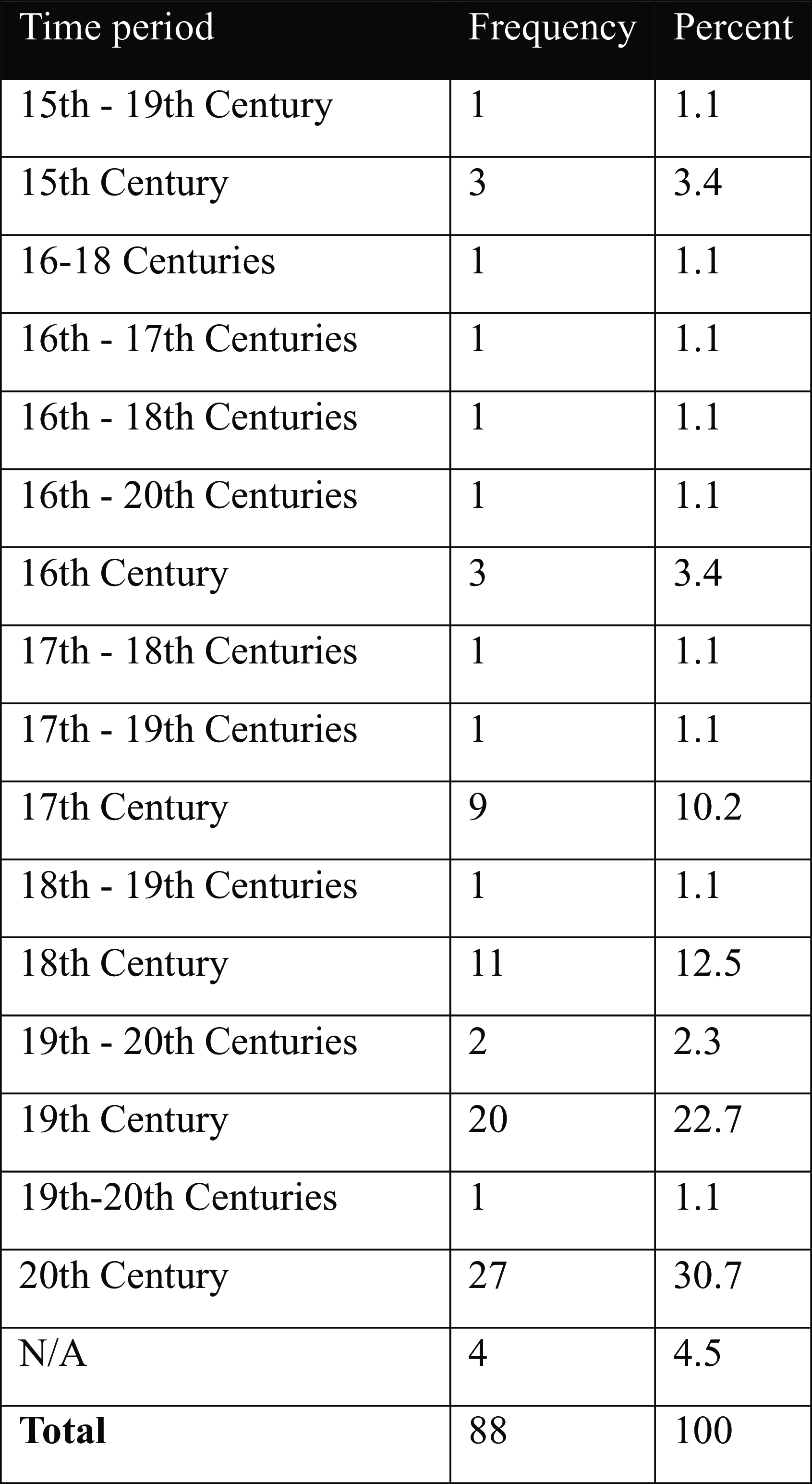

The regions and countries most frequently analyzed by women and gender historians in the journal are Mexico, followed by Argentina and Chile (Chart 2), and the time period most commonly studied in this scholarly field is the twentieth century (Chart 3).

Chart 2 The most frequently studied countries for analysis in The Americas from July 1944 to January 2024

Chart 3 The most frequently studied time periods for analysis in The Americas from July 1944 to January 2024

To identify and examine the major themes, categories, and methodologies used by Latin American historians to study women and gender histories in The Americas, this essay employed a text analysis methodology. This involved using the open-source web-based software Voyant Tools to count the frequency of words used in all 88 articles curated for this online edition. The text analysis was conducted for the three periods that showed the highest number of publications on women and gender histories in the journal. The purpose was to identify any continuities or changes in the most common categories used by historians during each period.

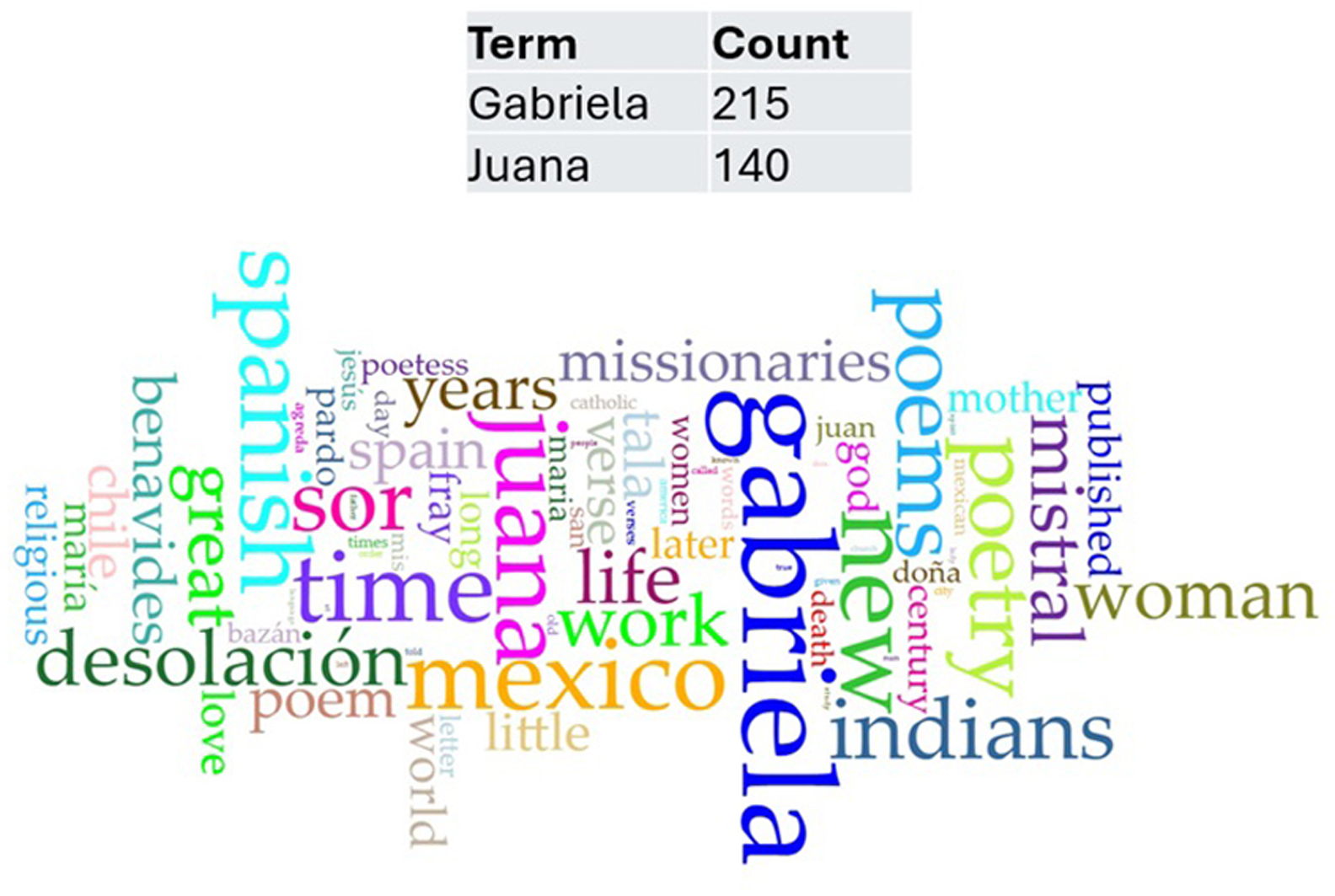

The first period spans from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s (Figure 1). Analyzing the articles from these decades through the tool of text analysis reveals that a majority of the publications during this time were focused on biographical accounts of notable female figures in Latin American history, with a particular focus on Gabriela Mistral and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Figure 1 Word analysis for the articles related to the period from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s

While scholars often track the origins of women’s history scholarship back to the 1970s,Footnote 10 it is worth noting that historians in The Americas demonstrated an early interest in women’s biographies and primary sources that could uncover the life experiences of Latin American women. It would be anachronistic to evaluate this early scholarship using paradigms and methods that emerged later and that would deeply interrogate the social dimensions and power relationships associated with the meanings of the category of “women.” Nevertheless, even though these early interventions perpetuated stereotypical ideas about Latin American women, such as the belief that North American women were more progressive than Latin American women,Footnote 11 or the emphasis on the physical beauty of Latin American women,Footnote 12 this early scholarship represented an intriguing beginning to the study of women’s history in the journal. In particular, these early works offer insight into the primary sources that would be crucial to trace women’s trajectories in Latin American past societies. For example, the article “Periodicals for Women in Mexico during the Nineteenth Century” by Jane Herrick provides a detailed description of nineteenth-century newspapers aimed at female readers and the main topics these periodicals addressed to educate women during that time.Footnote 13 Similarly, the 1963 piece by Anyda Marchant examines the life of Maria Graham, a captain’s widow who arrived in South America during the nineteenth century, using Graham’s journal.Footnote 14 Both periodicals and journals would become crucial primary sources for historians researching women and gender histories in the decades to come.

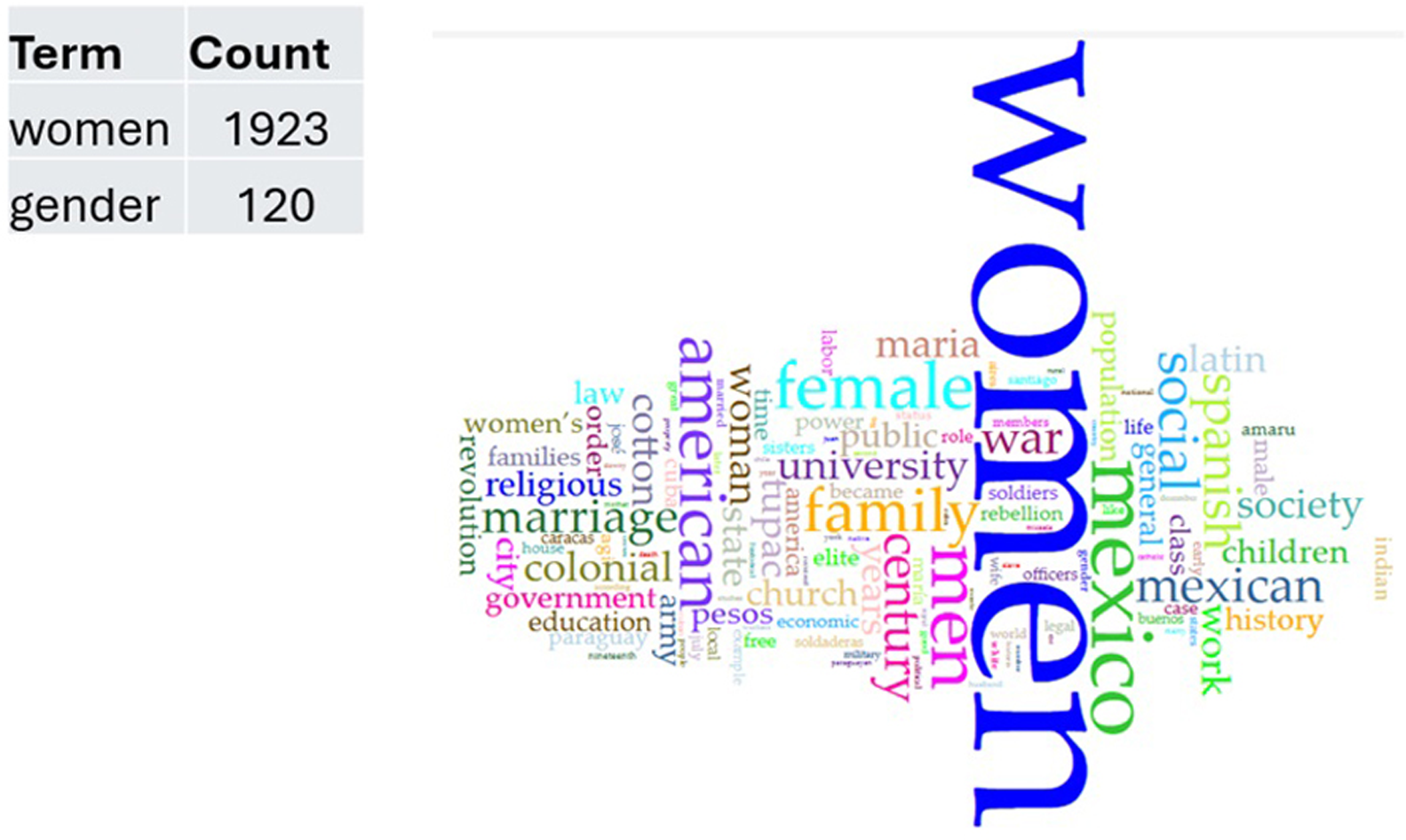

After these initial studies, and particularly following a significant decrease in publications on women’s history during the 1970s, the 1980s and 1990s marked the second period of increased publications (Figure 2). The text analysis of the articles shows that “women” was the primary focus during this period. In addition to “women”, the analysis indicates the prevalence of other concurrent categories such as “revolution,” “marriage,” “government,” “education,” “family,” “class,” “church,” and “war.” From Scott’s perspective, it is possible to say that, during these decades, academic production in The Americas revealed a growing interest in centering women in historical inquiry and constructing “her-stories” aimed at highlighting women’s role as agents in broader historical processes.

Figure 2 Word analysis for the articles related to the period from the 1980s to the 1990s

Examples of scholarship highlighting women’s essential roles in key historical events include research on women, wars, and revolutions in Latin America. For example, Anna Macias’s article on women and the Mexican Revolution highlights historians’ interest at the time in revisiting major historical events that were previously studied, but this time focusing on women’s perspectives and experiences. Macias explicitly addresses the silence of Mexican scholarship on women’s participation as active agents in the Revolution, tracing the multiple and complex roles played by women as leaders, soldaderas, and victims. According to Macias, “by ignoring the active participation of millions of women in the Mexican Revolution, historians have helped to perpetuate the myth of Mexican women as weak, inert, passive and dependent human beings.”Footnote 15 As in the case of Macia’s article, during these decades, her-stories on women’s roles in wars and revolutions aimed to restore agency to women and address the silences, myths, and stereotypes that had been prevalent in previous historical accounts. Along similar lines, Leon G. Campbell’s work discusses the role of women in the Great Rebellion in eighteenth-century Peru. The analysis includes a class perspective, highlighting differences in the experiences and perspectives of elite Spanish and creole women compared with those of native women.Footnote 16 Likewise, Barbara J. Ganson examines the various roles of women during the nineteenth-century Paraguayan war, specifically focusing on how women’s positions were influenced by their class, residency in rural or urban areas, and ethnic backgrounds.Footnote 17 These works challenge the idea of a singular definition of “women,” highlight the diverse experiences of Latin American women in the war and revolutions, and demonstrate how the histories of women in The Americas studied the category of “women” not as a uniform experience taken for granted but rather as a complex social construct rooted in relationships to class and ethnic positionalities.

Furthermore, the academic production of The Americas from the 1980s and 1990s also reveals a strong focus on studying the intersections between gender and class in Latin American societies. This was in line with the broader trends in Latin American scholarship at that time.Footnote 18 Examples of these studies include John Tutino’s analysis of the Mexican elite from a perspective centering on family and kinship networks,Footnote 19 Dawn Keremitsis’s study of the sexual division of labor in the textile industry in Mexico and Colombia,Footnote 20 and Donna Guy’s piece on the industry of cotton and family labor in nineteenth-century Argentina.Footnote 21 These pieces of scholarship show how, as described by Caulfield, there was a significant increase in studies focusing on gender as an analytical category during the 1980s in the field of Latin American history.Footnote 22 Instead of solely focusing on “women,” these studies delve into gender relationships and their influence in shaping family structures, labor, and economic power and privilege in both urban and rural settings. Tinsman, John French, and Danny James have pointed out that the emergence of the gender category in Latin American history brought a focus on the important role of ideas and practices of femininity and masculinity, as well as the sexual division of labor, in shaping the region’s labor histories.Footnote 23 Histories of women and gender in The Americas during this period reveal this broader scholarly trend in the field.

Lastly, in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a growing focus on questioning the historical sources and their limitations and potential to explore women and gender histories in Latin America. In the words of Caulfield, during this time, historians of women and gender uncovered how “traditional theories and methods could not account for women’s experiences.”Footnote 24 The research from this time introduced new approaches to capture women’s voices and experiences by using previously unexplored primary sources or by re-evaluating traditional sources from a new light. Examples of this in The Americas include Tutino’s use of correspondence and wills to trace kinship networks and the formation of Mexican elites, as well as the agency of peasant women in achieving economic autonomy within their households in the eighteenth century.Footnote 25 Frank Salomon also utilized Ecuadorian Indian women’s wills as a strategy to “give a vivid voice to people whom history would otherwise leave mute.”Footnote 26

The final period marking a peak in articles on women and gender histories in The Americas ranges from the 2000s to the present (Figure 3). During this time, publications on these subjects have remained relatively constant. The word analysis shows that “women” is still the primary category of analysis, along with “gender,” “class,” “men,” “slaves,” “marriage,” “family,” “state,” “politics,” and others. The focus on labor histories and the connections between class and gender persisted, albeit with reduced representation compared with the previous period. An example of this is Bianca Premo’s study of the gendered dimensions of the mita in colonial Perú. In this paper, Premo examined the economic lives of Andean women to draw connections between gender and class in colonial societies.Footnote 27

Figure 3 Word analysis for the articles related to the period from the 2000s to the present

In this period, there is also a rise in publications that include the categories of state formation and modernity in studying the gender and class aspects of Latin American historical societies. According to Caulfield, historians during the 1990s and 2000s highlighted how social reforms in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries specifically targeted women as the central focus of moral education for the purpose of attaining civilization, progress, and modernization.Footnote 28 The Americas’s academic production during these decades reflects this major historiographical interest. For instance, in her 2007 article, Sandra Aguilar-Rodríguez examines the link between class and gender in nutrition programs in Mexico during the 1940s and 1950s. She delves into the impact of modernization policies on food practices among working mothers. Her research sheds light on the practices of state formation and modernity in an urban setting, bringing new dimensions into the examination of gender and class in Latin America.Footnote 29 Christine Ehrick’s study of programs of social assistance in twentieth-century Uruguay from the perspective of secular elite “ladies” committees is also an instance of this scholarship linking class, gender, and state formation analysis.Footnote 30 The article from Robert Buffington and Pablo Piccato discussing the interpretation of narratives surrounding the murder of a woman by other women in Mexico City sheds light on the influence of gender on modern views of crime, and offers insight into the connection between gender, class, and modernity in Latin America.Footnote 31

This era also saw historians taking an interest in studying the relationships of Latin American women with the state. They used primary sources such as criminal and judicial records, as well as popular literature to understand how women negotiated and challenged prevailing gender ideologies. Caulfield pointed out that academic work in this field since the 1990s has emphasized how subaltern women actively engaged and negotiated with the state and systems of power, rather than being passively submissive to gender expectations.Footnote 32 In The Americas, these discussions are reflected in articles such as Erin O’Connor’s piece on the negotiations and interpretations of indigenous men and indigenous widows in regard to the Ecuadorean state’s marriage laws at the end of the nineteenth century,Footnote 33 or Kathryn A. Sloan’s article on how working-class young women negotiated their marriage choices with their families and the state in nineteenth-century Oaxaca.Footnote 34 In addition, Jesse Hingson’s essay discusses how Argentinian women advocated for their property and citizenship rights before national authorities during the Rosas Era. The piece illustrates how “[women’s] legal maneuvers clearly challenged the images of hearth, home, and caregivers so central to the nineteenth century notion of womanhood.”Footnote 35 All of these pieces used court cases to explore the tensions, interactions, and negotiations between women and the state’s prevalent gender norms.

Tinsman argues that, in the 1990s and 2000s, Latin American historiography on women and gender focused on “asserting women as historical actors.”Footnote 36 During these decades, as shown by the historiography that delved into women’s relationships with the state, there was a continued focus on women’s agency in the academic production of The Americas. For example, the journal examined the contributions of prominent female figures in traditionally male-dominated fields such as science, politics, and the arts. Lee M. Penyak’s article discussed women’s involvement in the advancement of obstetrics medicine in nineteenth-century Mexico.Footnote 37 Ericka Kim Verba analyzed Violeta Parra’s journey as a singer and her interactions and tensions with European modernizing ideals.Footnote 38 Iñigo García-Bryce’s piece on the transnational activism of the Peruvian poet and political activist Magda Portal is also illuminating in terms of “the tensions and contradictions of being a woman in a male-dominated public sphere.”Footnote 39 Diego Javier Luis’s 2021 piece explores the crucial role of Afro-Mexican women in shaping spirituality practices in Acapulco during the seventeenth century. This article not only emphasizes the agency of Afro-Mexican women in everyday practices in Acapulco but also highlights their fundamental role in producing knowledge and epistemologies essential for coping with everyday life in the region.Footnote 40

Additionally, Tinsman argues that the Cold War context experienced by Latin American and Caribbean political activists and scholars led to a rise in publications on activism, human rights, violence, and militarism with a women’s history perspective during the 1990s and 2000s. Examples of this historiography in The Americas include Elizabeth Manley’s article on women’s local, national, and transnational activism during the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic,Footnote 41 and David Carey Jr.’s piece on rape during the dictatorship in Guatemala.Footnote 42

Lastly, in the 2000s and up to the present, The Americas’s focus on “women” as the main category of analysis continued. However, during these decades, there was also an increase in publications on masculinities, sexuality, gay studies, and fashion, expanding the scope of examination beyond “women.” In his 1997 reflection for the Conference on Latin American History (CLAH) published in The Americas, Roger N. Lancaster sheds light on the discussions surrounding gender in Latin American history at that time. For example, Lancaster talks about gender expectations for men in Nicaragua and argues that the ideal of masculinity in this country, which included the expectation for men to be the active participants in sexual intercourse, led to the stigmatization of male homosexuality because non-heterosexual men were seen as passive and feminine. Lancaster also encouraged Latin American gender historians to consider masculinities and sexuality beyond the North American context, and “to think of sexualities in Latin America less in terms of stable local identities and more in terms of ongoing volatile processes.”Footnote 43

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, scholarship on sexuality and masculinities in The Americas included various works. Cristian Berco examined the links between sexuality and nation-building in nineteenth-century Argentina by tracing the legal changes in sodomy regulation,Footnote 44 Martha S. Santos focused on masculinity and honor in nineteenth-century rural Brazil,Footnote 45 and Jonathan D. Ablard discussed masculinity and nation-building in the policies of military service in Argentina during the early twentieth century.Footnote 46 All of these articles highlight honor as a central value that defined masculinity and gender hierarchy in Latin America. Additionally, Alfonso Salgado’s article examines the romantic lives, friendships, and feelings of love among young left-wing activists in Chile during the 1960s. It examines the role of sexuality, gender, and emotions in the formation of bonds and camaraderie among groups of young communists during that period.Footnote 47

The scope of gender and sexuality studies within The Americas has recently expanded to include studies on fashion and performance as sites where gender identities are disputed, negotiated, and performed on an everyday basis. Three significant scholarly works on this subject include Regina A. Root’s article, which delves into the concepts of beauty in fashion and print culture in late-nineteenth-century Buenos Aires.Footnote 48 Ageeth Sluis’s study of “Bataclanismo,” the French-inspired spectacle performed in postrevolutionary Mexico, sheds light on how theatrical performance permeated everyday life in early-twentieth-century Mexico and challenged traditional ideas of femininity in urban settings.Footnote 49 Francie Chassen-López’s 2014 piece introduces an ethnic approach to the study of fashion and gender by exploring how the dress of indigenous Zapotec women became a symbol of national identity in early-twentieth-century Mexico.Footnote 50

The output of academic work in The Americas reflects the key discussions, analysis categories, and trends on women and gender histories in Latin American scholarship. The analysis of The Americas’s articles aligns with previous studies in the field, showing that Latin American historians have primarily focused on “women” rather than “gender” as the main category of analysis. The transition from “women” to “gender” in Latin American historiography has not followed a linear path but has instead been influenced by the context of Latin American societies and by the scholarly and political commitment to asserting women’s agency in history. Yet, instead of assuming a timeless essence common to all women, Latin American historians have contextualized the category of “women” and demonstrated its intersections with class and racial and ethnic systems of power and social structures. Furthermore, the development of the gender perspective in the realm of Latin American history has yielded valuable insights into new pathways for the field. This includes the examination of masculinities, gay and queer studies, and research on the history of fashion. During the last few decades, publications in The Americas have increasingly expanded their scope to include gender as a category, exploring its potential to analyze systems of power, knowledge production, and political identities in Latin America.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/tam.2024.185.