Introduction

Nicoletta F. Gullace

Following the death of Elizabeth II on 8 September 2022, the emotions on both sides of the Atlantic and throughout the Commonwealth were overwhelming, though not necessarily aligned. Even as the primary emotion was one of sadness, people experienced the loss in different ways, shaped by age, gender, identity, and political context.

Many of us who were invited to comment in the news media came to the job of royal punditry from different places in the profession. Some, like Arianne Chernock, were actual experts on the crown, offering both popular and scholarly perspectives on the queen's death as well as commentary on the modern intersection of gender and sovereignty. Others, like Laura Beers, were smart, knowledgeable, and willing to work in a variety of media from television to print and able to offer insights on British history and culture from a major metropolitan news hub. Radhika Natarajan's research and commentary on race, gender, decolonization, and the Commonwealth make her an insightful critic of the crown's relationship to its former empire. Her perspective turns the nostalgic retrospective look at the queen on its head in fascinating and unexpected ways. My own research is situated in the Edwardian period and World War I. I came to royal commentary not through scholarship but because of my expertise on Downton Abbey. Downton led to The Crown, The Crown led to the queen, and soon I was covering royal funerals. Like the royal family itself, I have jumped the fact/fiction continuum.

The four of us came together at a quickly convened panel at the North American Conference on British Studies in Chicago on 13 November 2022, which provided the occasion to reflect on the meaning of the monarch's death—culturally, politically, socially, personally, and professionally. Our reflections thus come from different perspectives, and we hope they will provoke open-ended discussion unconstrained by the expectations of the press.

Mourning Elizabeth II: Meaning and Memory in Postimperial Britain

Nicoletta F. Gullace

My cousin lives on the family farm in a parish where I used to attend Conservative ladies’ strawberry teas decades ago with my grandmother. Although my family was strongly anti-Brexit, they are staunch Tories with proper respect for the monarchy. I was nevertheless surprised on 8 September when my usually stoic cousin confided how upset she was about the death of the queen. “This is now the oddest time here. It feels surreal as it seemed she would go on for years yet.” My cousin and her husband had taken a pilgrimage to Windsor just weeks before, and “it is all feeling very emotional.” A few days later, she said, “I am watching the vigil round her coffin, goodness it's hard.”Footnote 1

Her feelings resonated with the remarks from the labyrinthine queue formed to accommodate the tens of thousands of mourners who stood in line for hours to pay their final respects to the monarch as she lay in state at Westminster Hall.Footnote 2 Many spoke of thanking her for her service and honoring her commitment to duty. Others had a memory of seeing her at some point in their lives, and some explained that they were present for the sake of a parent or grandparent who would have wanted them to show their gratitude—a sentiment shared by the football star David Beckham, who queued for fourteen hours to walk past the coffin.Footnote 3 For twelve days, time in Britain slowed to the pace of a dirge, mourning rituals dominated the airwaves, and viewers followed the queen's body from Balmoral through Edinburgh to Buckingham Palace and Westminster Hall, pulled on a gun carriage by sailors to her funeral in Westminster Abbey and later to Wellington Arch, then finally—privately—to her grave at Windsor. With such an elaborate death ritual and well-rehearsed pageantry of mourning, her death ought to have had the finality that has historically allowed the crown to pass from one monarch to the next: “The king is dead; long live the king!”

Not since the time of the pharaohs, it seems, have monarchs enjoyed such rich afterlives as have Britain's modern royalty. Even as the nation moves on, it is not impossible that the queen will transcend death as Diana has done. I am thinking of the genre one might call “Diana necrophilia”: the continual use of images of the dead princess on People magazine covers; through endless biopics; in retrospectives sold at grocery-store checkouts; and on social media, where whole channels are dedicated to royals—living and dead, real and imagined, often intertwined as though they inhabited the same dimension. Clearly, images of Diana are as lucrative now, in the form of clickbait and journal sales, as they were twenty-five years ago, when paparazzi hunted her down in a Paris underpass. In Jean-Pierre Jeunet's romantic comedy Amélie, the protagonist claims she is circulating a petition “to canonize Lady Di.” Indeed, the cult of Diana has much in common with the cult of Diego Maradona or the veneration of Padre Pio through an endless array of candles, plates, and pictures available for purchase in shops and market stalls all over Italy. Sainthood and celebrity live side by side in the modern world. On Remembrance Sunday, gargantuan images of the queen were projected in Albert Hall, allowing the dead queen herself to give a Remembrance Day message.Footnote 4 It is early days yet, but as the queen rests in peace, it appears her image will labor on.

The queen's death at age ninety-six should have come as no surprise, though many claimed they were shocked and wished to know the cause. The meeting at Balmoral with Prime Minister Liz Truss—a woman born nearly one hundred years after Elizabeth's first prime minister, Winston Churchill—seemed to signal preternatural vitality rather than inevitable decline. People saw what they wished at this meeting, reassuring themselves that the failing queen of the recent Platinum Jubilee was quite recovered and would chug on as long as her mother had.

The outpouring of grief and gratitude following the queen's death seems to have been deep, authentic, and widespread. Such sadness, however, was felt unevenly in Commonwealth countries, where tributes from an older generation were intermixed with bitterness from nationalists, republicans, and younger critics of the monarchy, who expressed abiding anger over the legacies of empire and slavery.Footnote 5 The contrast between official messages of condolence, echoed in nostalgic interviews with mourners of all races from throughout the Commonwealth, and the reactions of those who saw only irony in tears shed over a monarchy they held responsible for exploitation and poverty, was stark and confusing. “The world has lost a global matriarch, who was a steadying and constant force through many crises and periods of difficulty,” wrote Prime Minister Andrew Holness of Jamaica, only weeks after he had demanded an apology and reparations for slavery during a visit from the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge.Footnote 6 Similarly, President Sandra Mason of Barbados noted that “her reign will forever represent the kind of stoic determination our world has required of its leaders . . . but which, sadly, we have not always been able to witness . . . We may all find a most valuable lesson in the strength of character and concern for humanity that was so much a feature of her 70 years on the British throne.”Footnote 7

Such statements from republican and republican-leaning leaders offering courteous accolades for the queen (rather than praise for the institution of the monarchy) did little to assuage doubts about the resilience of the crown beyond English shores. With the queen's death, inauspicious omens like William and Kate's ill-fated Caribbean tour became relentless background noise to epic questions regarding the future of the monarchy and whether it would survive in its current form. The Caribbean tour, a Platinum Jubilee homage choreographed to mimic the queen's own successful visit in 1953, was widely regarded as a “charm offensive,” meant to “persuade” other islands not to “follow Barbados in ditching [the] monarchy” as that nation had done in 2021.Footnote 8 Much of the trip was orchestrated by planners who failed to comprehend changing attitudes toward the monarchy among Commonwealth subjects. Riding through Kingston in the same open-top Land Rover that transported the queen and Prince Philip during a 1962 royal tour, Will and Kate, clad in gleaming white, realized too late the dissonant undertones of their imperial cosplay. Rather than offering a charming homage to continuity and connection, the viceregal image only highlighted the dated—and, to many, insulting—quality of colonial spectacle.Footnote 9

Why had a formula that worked for so long failed in the hands of the most popular of the younger royals? Or perhaps more curiously, why had the queen's seventy-year reign so successfully papered over some of the many contradictions of a modern monarchy? While by no means universally popular—particularly when her image reached its nadir after the death of Princess Diana—Elizabeth nevertheless resurrected herself in the years following as an iconic symbol of continuity, stability, and even compassion. Given that none of the other living royals has achieved anything like this apotheosis, what does losing the queen mean for those who loved her? Despite the incongruity of a democratic monarchy, she succeeded spectacularly in branding the crown domestically, internationally, and among a generation in the Commonwealth who bought into her transformative vision of a new kind of empire. Examining the sources of her endurance suggests that Her Majesty's popular appeal will not be easy for her successors to replicate.

Queen of Hearts and Minds

From the mid-1940s on, the young woman who would become queen reaffirmed Britain's sense of national identity, battered by the Second World War, economic turmoil, and postwar dependence on the United States. As David Cannadine so astutely notes in his classic work on the modern monarchy, the crown was “a comfortable palliative to the loss of world power status.”Footnote 10 Offering continuity and a sense of personal well-being, Elizabeth became a symbol of tradition, even as she, too, faced the challenges of modernity in her roles as wife, mother, and monarch.Footnote 11 As head of the Church of England, the British state, and the Commonwealth of Nations, her constitutional role was a unifying one that offered Britons the reassuring sense that, no matter how bad things got, there was an adult in the room, a figure whose unquestionable devotion to her people's well-being would enable them to carry on. “While people can see the gloved hand waving from the golden coach,” observed D. C. Cooper, “they feel assured that all is well with the nation whatever its true state.”Footnote 12

The queen's role, however, was far from passive. Elizabeth took the throne during the wrenching decade between the loss of India and the Suez crisis (1947–1956), when the British Empire operated like a phantom limb—shot off in battle but the body as yet unaware it is gone. Her engagement to the handsome Prince Philip stoked joyous outpourings, even as the partition of India and Pakistan left a trail of blood in the wake of Britain's “shameful flight.”Footnote 13 With wartime rationing still in effect at home, the royal wedding was a welcome distraction from the bleakness of austerity and sobering news from a crumbling Asian empire. Young women from all over the country sent the twenty-one-year-old Elizabeth their dress-ration coupons so that she could have a gown fit for a princess. While the transfer of coupons was prohibited, requiring the palace to return the kindly meant gifts, the gesture shows the vicarious pleasure that women—many of whom would be young brides themselves—enjoyed from participating materially in this happy event. Indeed, Princess Elizabeth's wedding offered consolation and hope during a time of lingering shortages and worrying news from abroad. Sugar for the “10,000-mile wedding cake” arrived courtesy of the Australian Girl Guides Association, and Queensland's governor sent five hundred tins of pineapple, “to be distributed through the United Kingdom, to certain charities of which Princess Elizabeth was patron.”Footnote 14 The royal couple received over twenty-five hundred wedding presents from all over the world, including one from Mahatma Gandhi, who sent a piece of cotton lace he had spun, embroidered with the words “Jai Hind” (Victory for India).Footnote 15

While the empire retreated and the so-called jewel in the crown shed colonial rule, Britons crowded around radios, televisions, and cinema screens, and thronged in front of Buckingham Palace to catch a glimpse of their bejeweled princess, whose splendor offered reassurance that British greatness endured. The harnessing of majesty and spectacle culminated in Elizabeth's splendid three-hour coronation of 1953. Winston Churchill believed the young queen's beauty and charisma had the potential to summon a second Elizabethan age, cheering Britons through a time of tremendous challenge.Footnote 16 Although the empire was beginning to collapse, the magnificent jewels, golden orbs, challises, and priceless crowns—some adorned with gems looted from the empire—proclaimed the exceptional wealth and grandeur of the monarchy. Housed in the ancient Tower of London, the crown jewels evoked an unbroken connection to a heroic past. As Cannadine perceptively noted, “When watching a great royal occasion, impeccably planned, faultlessly executed, and with a commentary stressing (however mistakenly) the historic continuity with those former days of Britain's greatness, it is almost possible to believe that they have not entirely vanished.”Footnote 17 The epic events of the queen's life—her beautiful wedding, the magnificent and divinely blessed coronation, august parliamentary openings, opulent ceremonial occasions at Buckingham Palace, and the jubilee milestones celebrating her reign—summoned a proud sense of British identity and celebrated the enduring spectacle of national greatness.

Nowhere was this more evident than in the queen's role as head of the Commonwealth—a title considerably more modest than empress of India, which Victoria had borne, but nonetheless claiming for Britain a continued (albeit transformed) imperial role.Footnote 18 By imagining the Commonwealth as a new version of benevolent empire, Elizabeth insisted almost through a force of will that former colonies and the mother country would remain united as part of a “great imperial family to which we all belong.”Footnote 19 “If we go forward together with an unwavering faith, a high courage, and a quiet heart,” the young Elizabeth declared in her twenty-first birthday address from South Africa, “we shall be able to make of this ancient commonwealth, which we all love so dearly, an even grander thing—more free, more prosperous, more happy and a more powerful influence for good in the world—than it has been in the greatest days of our forefathers.”Footnote 20 Maya Jasanoff has trenchantly deconstructed the notion of a “white queen” smiling down upon her adoring Black subjects during Commonwealth journeys that resonated with the lingering imagery of a rapacious empire. “[W]e should not romanticize her era,” notes Jasanoff. “For the queen was also an image . . . By design as much as by accident . . . [she] put a stolid traditionalist front over decades of violent upheaval. As such, the queen helped obscure a bloody history of decolonization whose proportions and legacies have yet to be adequately acknowledged.”Footnote 21 Few modern British historians would question this assertion.Footnote 22

Yet Elizabeth's desire to weld together a Commonwealth under the crown made her a different kind of queen. In her Christmas message from New Zealand in 1953, she insisted that “the Commonwealth bears no resemblance to the Empires of the past. It is an entirely new conception . . . [T]o that conception of an equal partnership of nations and races I shall give myself heart and soul every day of my life.”Footnote 23 In the wake of contemporary accusations of racism in the royal family, it is important to remember that Elizabeth's desire to foster the goodwill of Commonwealth nations and to shore up dwindling allegiance to her sovereignty spurred her to project a greater sense of inclusivity than her generational peers. Although Jasanoff has rightly noted that the Commonwealth bore more resemblance to the empire than Elizabeth was inclined to acknowledge, her personal repudiation of racism, her desire to “see . . . the people and countries of the Commonwealth and Empire, to learn at first hand something of their triumphs and difficulties and something of their hopes and fears,” and to show that “the Crown is not merely an abstract symbol of our unity but a personal and living bond between you and me,” may have won the hearts of subject long accustomed to being treated with indifference and contempt.Footnote 24

If there is one reason so many people of color lamented her death, it could be that she—unlike her predecessors and contemporaries—danced with an African president (Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana) in 1961; embarked on lengthy pilgrimages of goodwill throughout the Commonwealth; favored a South African boycott in defiance of apartheid; and embraced Megan Markle, whose first assignments as a working royal were trips to Australia and South Africa, where she projected the image of a new, inclusive monarchy to adoring crowds. While none of these gestures erase the brutal lengths to which Britain went in order to retain its colonial empire in the 1950s and 1960s, the queen's projection of kindness and humility toward her non-white subjects may have won the affections of a generation not yet primed to demand restitution from the perpetrators of colonial violence. Prime Minister Gaston Browne of Antigua and Barbuda, who promptly informed King Charles of his government's desire to break with the crown, noted that the queen “was shown great affection by the people of our country on her visits.” “Her Majesty's leadership of the Commonwealth of Nations has been superb, joining the hands of the English-speaking states across continents and regions . . . Her ability to inspire and unite has been one of the many remarkable features of her life.”Footnote 25 However culpable the queen's image was in sugarcoating the asymmetrical configuration of imperial power, Elizabeth II—in word and gesture—allowed Commonwealth subjects to imagine a ruler who cared deeply about their welfare.

For those at home, the queen's seventy-year reign tied Britain to its past in affirming and positive ways untainted by self-reproach. Not only did she embrace a new kind of benevolent empire but her evocations of innocent patriotism extolled the values and virtues of a little England that would abide through the devotion of its queen and amity with its former colonies. “I cannot lead you into battle, I do not give you laws or administer justice,” she declared in her 1957 Christmas speech, “but I can do something else. I can give you my heart and my devotion to these old islands and to all the peoples of our brotherhood of nations.”Footnote 26 Such professions of devotion date back to her first wartime broadcast, encouraging child evacuees during the Blitz with warm wishes from home. On 13 October 1940, fourteen-year-old Elizabeth, after weeks of rehearsal, reminded children, “We are trying to do all we can to help our gallant sailors, soldiers, and airmen, and we are trying, too, to bear our own share of the danger and sadness of war.”Footnote 27 Given this mighty task, she assured her young listeners, “in the end all will be well; for God will care for us and give us victory and peace.”Footnote 28 Seven year later, her evocation of the war was more circumspect but no less heartening. Addressing “all the young men and women who . . . have grown up like me in the terrible and glorious years of the second world war,” she extolled the “joy” of taking “some of the burden off the shoulders of our elders.” Most importantly, she heartened her young compatriots, beseeching them not to “be daunted by the anxieties and hardships that the war has left behind . . . We know that these things are the price we cheerfully undertook to pay for the high honour of standing alone, seven years ago, in defense of the liberty of the world.”Footnote 29

While historians regard these representations of British heroism as central to “the myth” of World War II, Elizabeth's evocation of the British spirit felt real enough to many who remembered the war and has become part of Britain's cultural memory, even among those born long after the last bombs had fallen.Footnote 30 Royal addresses to the nation and Commonwealth during and after the war and Elizabeth's own contributions to the war effort ineluctably tied her to the generation of World War II, an association not forgotten by those who mourned her death. Those who claim to have no idea what the queen believed need only listen to her many speeches. Although she did not write them herself, and each surely required heavy vetting by the palace bureaucracy, her words over the decades consistently stress themes of unity, patriotism, courage, and compassion for her people—themes emblematic of the war generation.

For many mourners, standing in the queue to walk past her coffin was itself a way to come together as a community, resonant of cherished recollections of wartime unity. “If you go to Stansted Airport, you're in a queue for your holiday,” said seventy-eight-year-old Robin Wight to a reporter. “But here, this is not a queue, this is a magical moment we're all sharing together.” When he finished speaking, “thousands around him broke into (polite) applause.”Footnote 31 Historian Lucy Noakes, who has written extensively on British cultural memory of the Second World War, speculates that in mourning the queen, British people were also mourning “the generation of the Blitz,” now quickly disappearing, that held such a profound place in the national psyche.Footnote 32 During the war, Elizabeth served as a mechanic with the Territorial Army, linking her with the sense of community evoked by the war and explaining one facet of the repeated expressions of gratitude for her service—sentiments emerging, in part, from her connection with the World War II generation and the memory of their resilience on behalf of the nation. Joyce Skeete, seventy-four, met the queen as a girl in Barbados and felt that the monarch “has given her whole life to this country and all the other countries . . . I think, for her, it is worth queuing.”Footnote 33 Those who felt differently, of course, were not in the line. But to older Britons particularly, Elizabeth participated with bravery and a smile during a time of upheaval, cheering on Britain's children, reviewing the Guards at age sixteen, participating in the “myth of the Blitz” through her war work, and fostering the profound sense of community—even under separation, longing, and loss—that she would evoke again with such effect during the COVID-19 epidemic.Footnote 34

Navigating Monarchy and Mass Culture

While there were moments during the queen's seventy-year reign when economic downturn required the appearance of retrenchment from the crown, just as often the vicarious enjoyment of royal pageantry proved to be a consolation, uplifting spirits during dark times. Politics inflected how one felt about the expense of the crown, but under Elizabeth, there was never a serious move to abolish the monarchy. Indeed, the queen's political restraint allowed her to function with radically different prime ministers as a force seemingly above politics. To her proponents, she provided unity and stability for the country, even under a highly adversarial parliamentary system. Her presence at the opening of Parliament was a reminder of not only connection with an ermine-clad imperial past but also her subordination to the agenda of “Her Government,” regardless of where it sat on the political spectrum.Footnote 35 The queen's adherence to constitutional neutrality made her susceptible to imaginative speculation regarding her personal beliefs, while nevertheless providing a ballast during the scrum of electoral politics. Only once, in a disagreement with free-marketer Margaret Thatcher in July 1986 over a boycott of South African goods, which the queen supported in her capacity as head of the Commonwealth, was she seen to disagree with a sitting prime minister.Footnote 36

Even she did not always gauge public opinion correctly, however. For example, she failed to express sufficient public grief over the death of the divorced Princess Diana—a misstep some critics believe permanently damaged her reign. At the admonition of Prime Minister Tony Blair, the queen rectified her mistake in a touching tribute to the late Princess of Wales, somewhat calming the criticism that threatened her image as a figure at one with her people.Footnote 37 A resplendent royal funeral mollified the public, even as it traumatized Diana's young sons, forced by their father to walk in a cortege behind the coffin. From that moment, the queen began to recapture some of the warmth so successfully projected during the early years of her reign—a feat cemented at her Golden Jubilee in 2002. Thanking her people for their loyalty and support during her fifty years on the throne, she embarked on a forty-thousand-mile tour of the Commonwealth and expressed optimism about the future in a speech that echoed her coronation address. “I hope that this time of celebration in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth will not simply be an occasion to be nostalgic about the past,” she declared. “I believe . . . we have as much to look forward to with confidence and hope as we have to look back on with pride.”Footnote 38

In old age, Elizabeth deftly avoided media traps that ensnared many in her dynasty. Expertly navigating the elision of fact and fiction, she gamely interacted with James Bond and Paddington Bear and offered no response to the many films and programs that have fictionalized her life. The Uncommon Reader invented for her an entire internal life, as did Claire Foy, Olivia Colman, and—far more brutally—Imelda Staunton, yet without any comment as to what she thought or even whether she had viewed these imaginative renditions of herself.Footnote 39 She accepted her role as spectacle, evidenced in her preference for wearing bright—even fluorescent—clothing so each person in the thronging crowds who came to see her would be more likely to catch the desired glimpse of Her Majesty—a glimpse they would remember the rest of their lives. Beyond her carefully planned regal messages, what we know of her preferences comes in the form of trivia. She loved racehorses, enjoyed the companionship of corgis, preferred to live at Windsor, disliked wedge heels, and had a Dubonnet and gin daily until her physicians directed otherwise, but the public rarely saw her correcting the speculative narrative of her life, fictionalized for their entertainment.

Without her equanimity, can the crown survive The Crown—and all the other media that voraciously consume royal spectacle while fostering tabloid content that could prove fatal to the monarchy itself? The queen navigated the space between fact, fiction, and imagination without comment in a way her family has not succeeded in doing. Beginning with Charles and Diana, members of the royal family have succumbed to the irresistible desire to correct the record. Prince Phillip allegedly inquired about suing The Crown over an inaccurate portrayal of himself in early episodes. Prince Andrew offered a catastrophic television interview on his allegedly honorable friendship with a convicted pedophile who jetted friends to the Caribbean aboard a plane known as the Lolita Express. After Harry and Meghan aired accusations of racism during the infamous Oprah interview, Prince William blurted to reporters, “we are very much not a racist family”—a phrase instantly paired with photos of himself carried by Solomon Islanders in a sedan chair.Footnote 40 Indeed, the royals wrestle with the hydra of representation. Whether it be The Crown (partly fiction) or the Spare (ostensibly fact), the royal family seem to live in dread of both, particularly as they await Harry's memoir, widely touted as “raw and unflinching” and likely to expand upon the accusatory interview that Oprah diplomatically described as “their truth.”Footnote 41 With a voyeuristic and sensationalist media offering praise, pity, ridicule, and censure, correctional publicity seems only to confirm the sage advice to “never complain, never explain.”Footnote 42

If the queen navigated the media universe with more equanimity than her family, she also better understood the power of majesty to insulate the monarchy and tame the press. Charles—perhaps stuck in the time-loop of the Annus Horiibilus—promised a “slimmed down monarchy” to reduce the estimated £86 million in public funds spent on the Sovereign Grant, which supports the monarchy, its palaces, and its acolytes.Footnote 43 “We'll live in a flat above the shop,” he quips, explaining his plan to occupy small quarters in Buckingham Palace while throwing open the palace to the public.Footnote 44 Charles seems to believe he will be loved—or at least tolerated—if he asks, “what value is this offering the public?”Footnote 45 The modern monarchy Charles envisions will surely be less expensive, yet given that any price is likely too much for republicans, will the “slimmed down” monarchy offer the pageantry, majesty, and the sense of awe that reconciled Britons with their diminished status during the queen's seventy-year reign? Reporting on Tina Brown's perceptive suggestions for a US visit by William and Kate, Tim Teeman summarizes, “they must go maximum glam to win over America.”Footnote 46 The same might be said of the United Kingdom. While it has been over three centuries since the British crown was a divine right monarchy, anointed by God to rule on earth, the queen still carried a bit of that fairy dust. Charles has little of this divine aura, weathering cheers, boos, and pelted eggs during his walkabouts, even as well-wishers continue to shout “God Save the King!” In attempting to elevate the legitimate heirs of the House of Windsor above indignities hurled by their rivals in California, they may have no choice but to wield crown and scepter to eclipse their detractors. A modern suit-and-tie monarchy, focusing on the worthy but tread-worn platform issues favored by the young royals, is laudable, but even the much-hyped Earthshot prizes William bestowed in Boston did not garner the press coverage of Kate's green off-the-shoulder gown and her wearing of Diana's stunning emerald choker.Footnote 47

While there is much speculation over the fate of the monarchy under Charles, is there a downside to not having a monarchy? Given that most comparable dynasties withered after World War I, and Britain's continental rivals have thrived as republics, does it matter whether the British monarchy endures under Charles? Is excitement over the monarchy merely a distraction, as transient as a football match? For progressive historians, the monarchy offends a visceral republicanism. Knowledge of the horrors of empire, outrage over unconscious bias within the royal family and the institution of the palace, and the inherent racism of expecting the free descendants of slaves to pay homage to rulers whose forebears amassed hereditary wealth from colonial plantations all undercut arguments for the perpetuation of a monarchy in modern times. The death of the queen nevertheless inspired real sorrow among those who loved her as a symbol of the British nation at its best. What they interpreted as her sense of duty and her care for her people inspired hundreds of thousands to queue up for hours and even days to pay respects by walking past her coffin in Westminster Hall.

When the queen died, what died with her? If US academics are reflexively cynical about the monarchy, many of our ordinary compatriots are not. Among those thronging crowds at the Platinum Jubilee were countless American women in paper tiaras, waiting for a glimpse of the monarch. In a republic where our own political divisions cannot be assuaged by a higher, neutral power, politics have become increasingly rabid, fierce, and irreconcilable. As a nation that has lived 150 years with the reactionary “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy, those in the United States might ask what nationalisms will the harsh realities of decline foster in Britain.Footnote 48 If the queen was able to ease painful self-recognition growing out of the loss of empire and Britain's decline as a great power, was she an obstacle to accountability or a balm able to heal psychic wounds that would become septic without the mythology she perpetuated? As Arianne Chernock has written, “Elizabeth was the glue that kept an otherwise fractious supranational entity together, just as many would argue that she continues to do today in ‘post-devolution’ Britain.”Footnote 49 In an age of devolution, can the United Kingdom remain united or the Commonwealth remain common, without a supranational source of allegiance to somehow hold it together? Audience members from Scotland, Wales, Canada, and Australia discussed the meaning of the monarchy for issues as diverse as Indigenous rights and independent membership in the European Union. As historians, we agreed that we are better at analyzing the past than forecasting the future, but as one participant noted, we should perhaps schedule another panel ten years from now to find out what it all meant.

What Did Elizabeth II Do for Women?

Arianne Chernock

I came to the monarchy in a very genuine scholarly way: through my first book, which was on male feminists in the eighteenth century. In that book, Men and the Making of Modern British Feminism, I was struck by how many of my Enlightenment subjects invoked the figure of the queen as a way of thinking more broadly about women's rights issues.Footnote 50 That is how I found my way to my next book, The Right to Rule and the Rights of Women,Footnote 51 and to my most recent research project, with the working title “Wake Up, Women! Women, Gender and Power at Queen Elizabeth II's Coronation.”

My comments, then, draw from my research and focus on Queen Elizabeth's complicated relationship with and to women, gender, and equality, and the legacies of these relationships. It is a subject I have been thinking a lot about since Queen Elizabeth II's death. To be honest, I have been in an argument with myself about the queen's feminist identity.

What is the queen's legacy on these important issues? One way I could spin this is to say that, actually, there is not much of a story here—or at least not a particularly interesting one. Elizabeth II was clearly quite conservative on issues of women and gender. She accepted her position because it was her duty, not because she seemed to want it. In fact, as a young girl she hoped that her parents would have a son so that she would not have to take on the role of sovereign. After her marriage, she tried to defer to Prince Philip whenever possible. During her reign, she supported women's causes in the mildest of terms. Her statements about women tended to be quite anodyne. Most recently, she seemed to waffle during the Prince Andrew sex scandal. In all of these respects, Elizabeth seems to have taken her cues from Queen Victoria. Like Victoria, she seems to have believed in patriarchy and the established gender order. Like Victoria, she saw herself as the exception, not the rule. And like Victoria, she always stressed that she was driven by duty to take on this more unconventional labor. In short, on the Woman Question, she was no Meghan or Diana.

So that is one version of the story. It is a disappointing one, and somewhat frustrating, too. But let me spin it a different way. It is true—Elizabeth did not say much on subjects of women, gender, and equality. But if we bracket what she said (or did not say) and focus instead on what she did, there is a more compelling story to tell. It is one about representation. From the start of her reign, it was clear that women—and not just women in Britain, but around the world—saw in the queen something that was disruptive, whether or not the queen herself wanted them to see her that way. Again, this had nothing to do with what Elizabeth said, but rather with the kinds of work that she was perceived as doing. She called the shots in her marriage, regardless of what kinds of negotiations went on behind closed doors. She did not give up her career once she married. Nor did she give it up when she began to have children; Charles and Anne watched their mother become queen. This, too, was highly unconventional during the 1940s and 1950s. Elizabeth was a mother and a head of state, head of the Commonwealth, and head of the Church of England.

Women, especially early in Elizabeth II's reign, took notice. This is why Margaret Thatcher penned a remarkable piece called “Wake up, Women” shortly after Elizabeth's ascension.Footnote 52 Thatcher—at that time, a young barrister—hoped that Elizabeth would provide a way forward for other professionally minded women, who could model their careers after hers and seek inspiration from her accomplishments. Thatcher was proud of how Elizabeth combined parenting and reigning.

I think Thatcher's piece helps us to understand why so many women showed up for Elizabeth's coronation and why they showed up again to pay their respects at her death seven decades later. Obviously, people queued in London for different reasons, but there was a strongly gendered element. Consider David Beckham, who, when interviewed, explained that he was queuing in part out of respect to his grandmother, who would have wanted him to be there. There is something particularly important here about the women of Elizabeth's generation—the World War II generation—who felt that they had been part of something together. They really did identify with Elizabeth as a meaningful point of connection; she helped them make sense of their own experiences. We should not discredit or discount this.

I want to push a bit further. I indicated before that we can put a more positive spin on Elizabeth's legacy for women and gender by focusing less on what she said and more on what she did. But what did she do?

It is actually hard to answer this question. We stress that Elizabeth worked hard, that she was selfless and she was dutiful. But what did she work hard at? What were her responsibilities? This is another place where I struggle. Because again, depending on my audience and mood, I play it both ways. I will start this time with the positive story.

There is no question that Elizabeth kept a demanding schedule. She met with her prime ministers; she followed parliamentary affairs; she engaged in diplomacy; she left her children for long periods of time to go on overseas trips; she proved adept at concealing her emotions; she attended many ribbon-cutting ceremonies; she grew old in the public eye; and she maintained her duties until the very end. This required real endurance. Think back to the image of Elizabeth meeting Liz Truss: it was just two days before her death. It is remarkable.

This list, however, does not provide a lot of details. And unfortunately, another way to think about what the queen did is that she did what would traditionally have been considered women's work, but on a more elevated stage. In performing the work of the sovereign, Elizabeth was essentially acting the part of a glorified first lady—a point that historian Charles Beem has made in his related work on this subject.Footnote 53 The role of first lady is not a very controversial one in the United States. Think about the ways in which Elizabeth was remembered: matriarch, mother, grandmother, and patron. What made Elizabeth a good constitutional sovereign—the reason she has received so much posthumous praise—turned on her so-called feminine qualities. Her sense of how to steer clear of politics, how not to intervene, how to use fashion to draw attention to herself, how to find just the right causes to support—these are some of the reasons that she received favorable reviews. Elizabeth was so successful as a queen, in other words, because being queen played to her perceived strengths as a woman. It was in her comfort zone. And that perceived comfort zone aligns with the roles and expectations associated with constitutional monarchy. There is a reason why the monarchy looks the way that it does today, and it has something—not everything, but something—to do with the fact that women have sat on the throne for the majority of the past two hundred years. It is not incidental. I am still trying to figure out what exactly this relationship is, but there is a relationship.

In this respect, praising the queen's particular interpretation of her role and remit can actually take on a bit of a paternalistic, if not misogynistic, quality. At her death in 1901, Queen Victoria was praised in a very similar fashion. And some of those who praised Victoria had very little interest in advancing women's careers or opportunities. Consider the novelist Thomas Hardy. In 1900, he recognized that Queen Victoria's reign was nearing its end and lamented the passing of the crown from mother to son (the scandal-prone Albert Edward). “As our Constitution has worked so much better under queens than kings,” he explained, “the Crown should by rights descend from woman to woman.”Footnote 54 This might seem to be an endorsement of female leadership, or at least of female competence, but in fact the reverse was the case. Hardy liked queens because, as women, they were the so-called softer sex and assumed to promote a culture of deference. Queens were (it would seem) easier to manage than kings in a modern political system, and they were much more likely to be popular. These characterizations of female sovereigns were a standard trope in Victorian discourse, as I explore in depth in The Right to Rule and the Rights of Women, noted above. As I discovered through my research, queens (and Victoria specifically) were regularly praised for being more ductile, instinctive, and accepting of the ceremonial aspects of their position and the routine tasks associated with it. The modern British monarchy is very much a feminized institution.

So these are the reasons I am conflicted when it comes to thinking about Queen Elizabeth II's legacies for women—and for gender questions more broadly.

Yet I am hopeful about future possibilities. And the reason I am hopeful is that Charles III's reign provides an opportunity. His reign, after all, is something of a gender experiment. How does a man navigate this now thoroughly feminized position? And how will watching a man in this role help us all think in more creative and productive ways about gender, leadership, and power? The optics were particularly good during Liz Truss's brief prime ministry, but even with Rishi Sunak as prime minister, there is still something, perhaps paradoxically, unsettling (in the best sense) about watching a man perform the work of king. It is refreshing to see a man chastised for engaging in politics and for meddling, reminded to choose his charities carefully, and questioned about his parenting skills and personal life. In short, Charles is a man in a woman's role. There is real potential here, then, to use Charles and his experiences to help us move beyond some of the gendered stereotypes and expectations that we have been grappling with for centuries.

The Commonwealth and the Queen

Radhika Natarajan

The Commonwealth was everywhere and nowhere at Queen Elizabeth II's funeral. Commonwealth heads of state attended. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Commonwealth troops led the procession of her coffin from the funeral service at Westminster Abbey to the internment at Windsor Castle. Commonwealth flags waved along the Mall. David Olusoga on the BBC said that the queen was the glue that held the Commonwealth together. Charged with explaining the Commonwealth to BBC audiences in Britain and around the world, Olusoga carefully outlined that not all fifty-six member states were former colonies. Each country had a unique history, and hundreds of languages were spoken throughout the Commonwealth. What they had in common, he argued, was the queen, the embodiment of duty, service, and constancy. Olusoga called her a “career woman” when it came to the Commonwealth. No one, he argued, understood the Commonwealth as well as did the queen.Footnote 55

In coverage of the funeral and retrospectives of her life, audiences were endlessly told how many countries Elizabeth visited and how many miles she traveled.Footnote 56 The Commonwealth was woven into the fabric of her reign. We heard her twenty-first birthday broadcast from Cape Town, in which she dedicated her life to service to the Commonwealth.Footnote 57 We watched footage of her trip to Kenya, interrupted by news of her father's death and her accession to the throne.Footnote 58 After her coronation in 1953, Elizabeth began the longest tour of her reign. Over six months, she traveled forty-four thousand miles and visited Bermuda, Jamaica, Fiji, Tonga, Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia, the Cocos Islands, Sri Lanka, Yemen, Uganda, Malta, and Gibraltar.

In her Christmas Day broadcast of 1953 from Auckland, she said, “The Commonwealth bears no resemblance to the empires of the past. It is an entirely new conception built on the highest qualities of the spirit of man: friendship, loyalty, and the desire for freedom and peace.”Footnote 59 Elizabeth emphasized a conscious shift from an organization based on a common history of empire to one built on shared, universal values. Her work as a traveling saleswoman of the Commonwealth continued with her Jubilee Tour in 1977, when she visited fourteen countries and traveled fifty-six thousand miles. While many websites, including the royal family's official site, present the statistics of individual tours, the sheer amount of travel seems impossible to calculate over a lifetime.Footnote 60

These numbers, a representation of the scale and size of the Commonwealth, stand in for a political organization that seems to defy rational explanation. What work does the endless repetition of numbers in accounts of Queen Elizabeth's service to the Commonwealth perform? In most of these accounts, numbers stand in for actual understanding of the Commonwealth as a political association, the nations that comprise it, the history that shaped it, or the future it wishes to build. The BBC's coverage of the funeral highlighted the hollowness of the Commonwealth as a signifier of the queen's global commitments. One of the video packages played repeatedly in the eleven days between the queen's death on 8 September and the funeral on 19 September 2022 showed footage of Elizabeth speaking in several languages of the Commonwealth, but these clips included no subtitles to translate what was said for the English-speaking audience of the BBC.Footnote 61 The content of her speeches did not matter to the BBC's news editors; what mattered was the image of Elizabeth speaking in non-English languages. At the funeral, the BBC presented heads of Commonwealth governments, but no names were listed in the chyron, no mention made of the nations these leaders represented. The Commonwealth was a cypher, for which unknowable languages and nameless people of color stood in for an empire that once was and symbolized the significance of the monarchy for continuing to hold its fragments together. The portrayal of Commonwealth as a heterogeneous jumble demands an explanation of how and why it holds together. For the BBC, the answer was simple: the queen.

The media serves the royal family's interest by portraying the monarch amid Commonwealth diversity, and these images call upon people of color to silently stand in for the former glory of empire. I know this maneuver, because I was once conscripted into this performance.

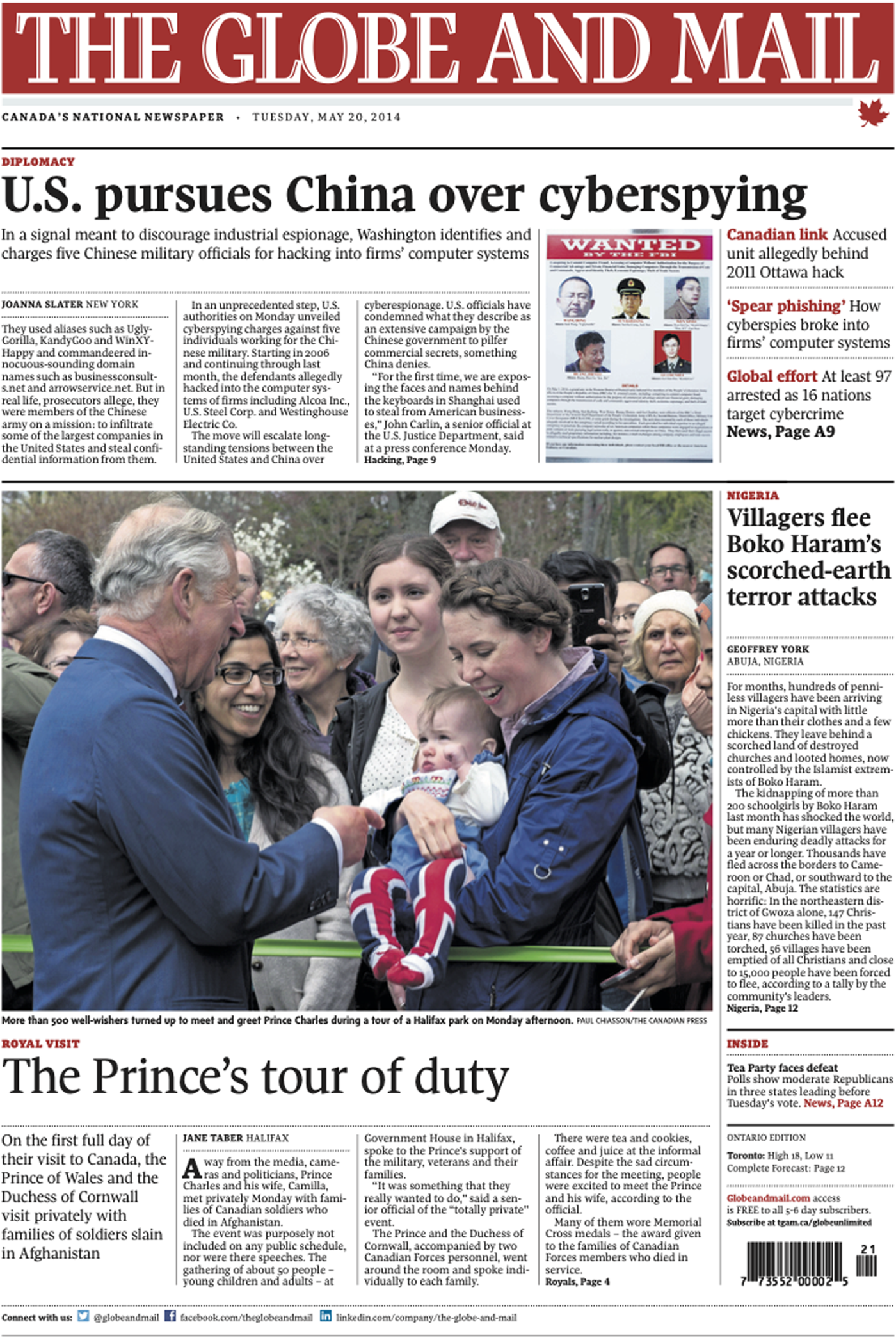

The 20 May 2014 front page of the Globe and Mail, which calls itself “Canada's National Paper,” featured a photograph that included me in a group of people meeting a member of the royal family (figure 1).Footnote 62 The previous day, Charles, at the time the Prince of Wales, visited Halifax, Nova Scotia, where I was then living. The headline connected Charles's visit to previous royal tours of the Commonwealth and emphasized the bonds of duty that connected the British monarchy to Canada. When we shift from allowing numbers to stand in for the relations of the Commonwealth, we open up more possibilities to interrogate the image work of the crown. The image the Globe and Mail chose to launch Charles's tour of Canada captured a young parent presenting a baby to the future sovereign. The timing of the visit is crucial to understanding this decision to represent Charles's visit to Nova Scotia through this one encounter. His four-day trip to Canada was meant to commemorate Canada's past and look ahead to the future. Our meeting took place three years after the wedding of his son William to Catherine, and at the time of the visit, his grandson and heir George was ten months old. This photograph calls back to the existence of that other baby, and viewers are reminded that the succession is secured for at least three generations. The continuity of the crown is wrapped in a family story, in which Charles as grandfather gestures to a future relation between Canada and the United Kingdom. The future is not necessarily a rosy one, however. The baby is not that excited by the encounter with the future sovereign, scowling and shaking a fist at the intrusive man. Charles's face is not fully shown in the photograph. He is the center of the photograph, but not quite its subject. The focus is the space between the prince and the baby, the relationship between future sovereign and subject.

Figure 1 Photo accompanying article by Jane Taber, “The Prince's Tour of Duty,” Globe and Mail, 20 May 2014, page 1. Photo credit: Paul Chasson/The Canadian Press. By permission.

The Globe and Mail had many photographs that could have been used to represent Charles's trip.Footnote 63 In addition to speeches, visits with farmers, and charities that support military families and survivors of domestic abuse, Charles and Camilla celebrated historical links between Nova Scotia and Britain. Specifically, they commemorated the beginnings of Scottish settlement of the newly conquered territories in 1773 and the links forged during World War II. Charles planted an English Oak in the Public Gardens, calling back to his grandfather George VI's efforts to do the same on a visit in 1939. Charles and Camilla lunched with World War II veterans and war brides at the Canadian Museum of Immigration.Footnote 64 The shared project of settler colonialism in North America and the imperial alliance stood in for the complex relations between Canada and the United Kingdom. Yet, despite the intended theme of the tour and solemnity of the day's occasions, the Globe and Mail chose a picture of the future sovereign encountering a baby wearing Union Jack socks.

On this particular day, the Globe and Mail chose to retreat from militarism and settler colonialism in order to represent the relationship between Canada and the crown through a domestic and familial frame. And in that project to domesticate the monarchy, I play an important role. Or at least, my image does. I could tell the story of how I came to be in this picture, but it does not actually matter. The explanation does not change the ideological work the presence of a person of color performs. In the composition of the photograph, I am firmly located between Charles and the baby, in the space of subjecthood, and yet I am placed outside of that relationship. I smile at the baby, perhaps at the Union Jack socks or her less than enthusiastic response to Charles. As a face in the crowd, the presence of the nonwhite figure signals Canada as a multiracial nation, but this presence grants permission to the primacy of the white subject's relationship with the sovereign. The inclusion of a person of color is thus also an exclusion. When we think about the choices that brought this photograph to the front page of Canada's national newspaper, we have to think carefully about the choice to depict the future sovereign in a multiracial setting. The nonwhite figure gestures to the imperial past as the basis of the Commonwealth association and asserts not the equality of subjects in relation to the crown but rather enduring racial hierarchy.

The visual iconography of the monarchy from the late nineteenth century created the illusion that inclusion could mean equality. We might recall the visual imagery of Queen Victoria at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition or with her Indian servants.Footnote 65 This was a choreography that was carefully restaged during decolonization through the endless images of Queen Elizabeth at independence events. Being photographed at those celebrations—receiving bouquets from children, dancing with Kwame Nkrumah—bestowed her approval of these events, as if it was her permission that allowed independence to proceed. If decolonization demanded a particular choreography, then so, too, did the monarch's relationship with the Commonwealth. In 1965, the Commonwealth Secretariat became an administration independent of the British government. As I discovered in research for my 2014 Journal of British Studies article on the Commonwealth Arts Festival of 1965, there is nothing natural about the relationship of the royal family and the Commonwealth. At the festival, held in Britain over three weeks, Prince Philip's schedule was carefully managed, and a great deal of attention was paid to deciding which events Queen Elizabeth would attend. In media coverage of the festival, Philip and Elizabeth stood in for the British viewer of Commonwealth art. The patronage of the monarchy confirmed the primacy of the white British viewer as the arbiter of Commonwealth art.Footnote 66 In Britain, the Commonwealth held the public's attention for the war underway between Pakistan and India and especially through the question of migration. Earlier that summer, a 1965 white paper further limited migration from the Commonwealth by creating quotas for the number of labor vouchers issued to migrants and limiting which relations qualified as dependence.Footnote 67 Performers who traveled to the United Kingdom for the festival were aware of the contradiction between the celebration of their presence in London for the arts festival and migration restriction. One performer asked, “What is a Commonwealth for if the wealth isn't held in common?”Footnote 68 Many in the Commonwealth might well ask the same question today.

If Elizabeth is the glue that holds the Commonwealth together, the success of that metaphor is an effect of a great deal of labor. If we do not take the relations depicted within photographs of the monarch and Commonwealth for granted, we realize that the Commonwealth does not need the monarch, but it is the monarch that needs the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth serves as a vehicle to convey the narrative of service and duty that was central to the image Elizabeth projected of herself. The Commonwealth provides a global role for the royal family, and by extension Britain. During the funeral coverage, the BBC focused on the presence of US president Biden particularly, but the presence of royalty and global leaders signaled a continued global role for Britain. But that role cannot be reduced to the image that the British state wishes to project of itself. In “The Dissolution of the British Empire,” William Roger Louis shows how British officials invested in making decolonization appear to be a process managed on British terms and timelines, to make it seem that independence was a sign of the success of British tutelage in self-government.Footnote 69 The queen also played her part in the managed dissolution of the empire. Her presence at independence day celebrations bestowed her approval to decolonization and helped preserve the prestige of British imperial rule. The passive language of dissolution masks the violence of decolonization, and when we allow the Commonwealth to stand as an empty signifier, we allow that narrative to continue.

When we talk about the Commonwealth through the queen, through the miles she traveled, and the countries she visited, we obscure what the Commonwealth is or what its independent members do. Can the Commonwealth refuse the relationship of recognition with the sovereign? Prince William and Catherine's visit to Jamaica points the way. In the Caribbean, calls for reparation are calls to acknowledge the history of slavery and to rewrite the history of empire. Jamaicans and a global public loudly critiqued the image of William in white tropical dress uniform riding in the same Land Rover that his grandmother toured Jamaica in during her Coronation tour in 1953. The outcry over the photograph showed an audience that refused to accept the visual choreography of Elizabeth's era.Footnote 70 My own conscription into the monarchy's service shows that the most banal of images, perhaps because we have come to read them as boring, should be critiqued and contested. The hollowness of the Commonwealth's crown continues because we allow the repetition of scale and size of the Commonwealth and the pageantry of diversity of its inhabitants to stand in for a real engagement with the history of empire and decolonization.

The American Press and the Queen's Death: A Media Memoir

Laura Beers

The neighborhood where I live, just outside of Washington, DC, is very international and includes an outsized population from the Commonwealth. The night that the queen died was also the night of the back-to-school picnic, and I was sitting and talking to friends, who included a South Asian Kiwi, several Indians, a Sri Lankan, and a Nigerian, almost all of whom worked for the World Bank, which I think is significant in terms of the global reach of the Commonwealth and the new international networks in which older imperial elites are proportionately overrepresented.

Not one of them was shedding a tear for the death of the monarch. But several, including a South Asian woman who had grown up in London, said that American friends had been sending texts all day asking if they were all right, a well-meaning sentiment that reflected Americans’ perception of the centrality of the monarch in the lives of her subjects, but one that my friend nonetheless thought was insane.

In the discussion that followed our opening comments at the roundtable of the North American Conference on British Studies in November 2022, there were several interventions that called me out for failing to acknowledge the sincerity of the grief that many people felt at the death of the monarch. One member of the audience suggested, I think correctly, that the queen's passing served as a cathartic moment for people to mourn the losses of the previous two years of the pandemic. The queen, in effect, became a metonymy for the more than two hundred thousand of her subjects who had lost their lives from the virus. In mourning her passing, people were in reality mourning something else. This is doubtless true—certainly I suspect that it was the case with one of my British colleagues who very unexpectedly announced on Twitter that she was sobbing at the news of the queen's passing—but, in that it is true, it does not bolster the argument that people thought that the queen was herself a significant figure to be mourned.

Others in the discussion emphasized that grieving for the queen was a real phenomenon, that there were many real Britons and members of the Commonwealth realms who felt the passing of the queen as a personal loss, as if the monarch were someone with whom they had an intimate relationship. Again, I do not dispute that this was true for many, but I suspect that the many for whom it was true were in the vast majority white and over sixty, and that, in a Venn diagram with Brexit voters, they would be found to overlap significantly. Most of those who came of age in either Britain or the Commonwealth in the aftermath of empire did not feel the queen's loss personally, and, certainly, the average American did not mourn her loss as a personal tragedy—which brings me back to the original theme of my comments, the American media's reaction to the queen's death.

I would like to talk about America's visions of Britain and also the ways in which the media was complicit in not only reflecting but also perpetuating those images. In the weeks following the queen's death, I became, bizarrely, a national television pundit.

I write occasionally for CNN, mostly about the politics of gender, a central area of my research, and about comparative American and British politics. Less than a week before the passing of the queen, I had written a piece about what Liz Truss's premiership—which no one foresaw at that point was going to be as short-lived as it ultimately was—was likely to mean for women, and particularly for working-class women. The piece considered the likely disproportionate impact that the reduction in universal credit that a Truss premiership portended would have on working-class women, and what her own self-professed identity as a “Destiny's Child feminist”—who believed that all you needed was for “All the women, Independent, [to] throw your hands up at me” and everything would be okay—would mean for British women.

So, having just written this, on the morning when it was announced that the family was traveling up to Scotland to be with the monarch, CNN called and asked me if I could write something quickly about the monarch's life and the significance of her death, as it looked like she was on her way out. They wanted something that they could throw up on the website as soon as the news broke that she had passed away.

I initially told my editor I was perhaps not the best person for the task. When it came to the monarchy, I was a small-r republican, who viewed the queen as a waste of taxpayer money. They responded by saying that I didn't have to venerate her, but it would be great if I could talk about the way, over her reign, Britain transitioned from empire to Commonwealth, and how she helped the country remain relevant as it ceased to be a superpower. I sat down to write a piece on how the queen had reigned over Britain's transition from great power to nation state, from empire to Commonwealth, through the Swinging Sixties and Cool Britannia. Edited out of my piece was the fact that David Bowie returned his knighthood. Kept in was the fact that Mick Jagger did not. Then it ended with a discussion about the future of the Commonwealth and the monarchy more generally, making the point that opinion polling in several of the Commonwealth realms taken shortly before the queen's passing suggested that they would not necessarily be on board with a King Charles.

The piece went up online the day that the queen died. The image of the queen meeting with the Spice Girls was used as click bait. That piece, in turn, led to a series of calls from national cable news networks to come on and talk about the future of the monarchy. And what I thought was really interesting about this media frenzy was how insincere the networks were about their coverage of the queen. For nearly two weeks between the queen's passing on 8 September and her funeral on 19 September, the major US cable news channels talked about almost nothing else. If you were an alien come to America from Mars, you would be forgiven for thinking that the death of Queen Elizabeth was of momentous import to twenty-first-century Americans, or, at the very least, to those who controlled their news media.

But while the newscasters were seriously, or at least with straight faces, dissecting aspect after aspect of the queen's passing while the cameras rolled, as soon as they cut to commercials, they would drop their professionalism and say to me things like, “Do you think the whole thing [British monarchy] is going to fall apart?” or “How much longer are these guys going to go on with this?” There was also a lot of conversation about what a Liz Truss premiership would mean for the British people.

Then we would come back on air and return to a superficial discussion of the queen. There was, to the news stations’ credit, some critical discussion of the future of the monarchy and of the Commonwealth, but on a fairly superficial level.

There was very much a feeling in all of this news coverage that this is what Americans wanted to imagine Britain as. Clearly these journalists would have liked for me to be able to talk about what a Liz Truss premiership portended for Britain, but they knew that an American audience did not care about that. Rather, they had a certain idea of Britain, which was to do with pageantry, with an archaic, glorified past being replicated in twee ways with carriages processing down Whitehall and people in kilts playing funny instruments at the funeral. There was a narrative that they felt they had to stick to, even though the journalists themselves did not buy into it.

The American news media was reflecting but also perpetuating this narrative. They were very much complicit in this is what America thinks Britain is, because they were not talking about the serious political and economic crises facing Britain: it was simply, all queen, all the time.

A week later, I did a prerecorded spot for The Situation Room, and, similarly, the journalist who recorded it with me clearly did not feel the queen's passing to be a major tragedy. When I asked him about what it felt like to have to feed this nonstop media narrative, he was philosophical. The previous week, he said, it had been All Mar-a-Lago, all the time. And next week it moved on to being something else nonstop. And he was right: as soon as the queen was ceremoniously laid in the ground, the American media frenzy stopped, and I went back to being an anonymous academic going about her life.

Except, not quite. Interestingly, the news network that wanted to talk to me when Liz Truss resigned from office a month after the queen's funeral was the BBC. The World Service was still interested in Britain when it was the politics of Britain that would affect the lives of people in meaningful ways, through their pocketbooks, their access to renegotiated mortgages, and funding for their local social services. That story was not of interest to American cable news. Only the BBC wanted to talk in detail about developments that would impact the lives of Britons in a material way. (And here I will own that it is clearly a reflection of my own background as a political and labor historian that I am inclined to believe that those material impacts inherently have more import than the cultural impacts of the queen's passing.)

The World Service's interest in Liz Truss does not, however, indicate that the British news media was immune from the superficial frenzy of reporting that surrounded the queen's death—far from it. Nor were other key institutions of twenty-first century British society.

The calls for my opinion in the wake of the queen's passing were inspired, in part, because I had a reputation as a scholar of women and politics, and the queen, of course, was a woman head of state. As a scholar of women and politics, I went to Britain in early September to give a keynote at the conference “Breaking the Glass Chamber” at Queen Mary, University of London, at which various women serving in the Commons and the Lords were also speaking. The event had been on the books for a year but was almost canceled out of institutional concerns that it would be inappropriate to come together and talk about women's impact on politics in the wake of the queen's death. Ultimately, the event did go forward, although, as we know, many other scheduled events did not, from the planned national railway strike to long-scheduled National Health Service surgeries, whose patients, once bumped from the rota, could not easily be penciled back in after the moment of national mourning had passed.

I think that these seemingly knee-jerk cancellations raise some serious questions about what was being performed and for whom as both the US news media and the United Kingdom writ large fell into a collective overreaction in the wake of the queen's death.

Allegedly, the queen was significant in large part because of how she changed images of women in modern Britain and acted as an inspiration for a generation of young women to combine motherhood and duties outside the home. And yet, there was initial discussion of cancelling an event literally conceived as a forum to discuss women's changing role in society because it fell a week after the queen's passing. The queen was meant to be respected and mourned in part because of her role, such as it was, in overseeing Britain's transition from empire to welfare state, and yet ironically it was seen as appropriate to honor her passing by denying Britons access to National Health Service care. The queen was lauded for her duty and sacrifice to the nation, as if her work as face of the nation and Commonwealth were an act of charity, yet she and her family were compensated over £100 million by the British taxpayer for expenses related to those duties in 2021–22. Meanwhile, the average pay for members of the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers is £36,000 a year; yet within the moral economy of 2022 Britain, it was these workers who were expected to sacrifice their planned industrial action to show support and solidarity for the royal family.

I am not denying that many people in Britain and beyond felt the queen's passing as a personal loss, but I do question how much relation the performative hysteria around her passing—both in Britain and beyond its borders—bore to that sense of loss.

I would like to question what that means—that both British society more broadly, from universities to the National Health Service to trade unions, and, in my own national context, the US cable news media—allowed itself to get so wrapped up in a narrative of hysterical feudal mourning that it knew to be artificial and intentionally misleading about the sentiments of many Britons. Speaking specifically to the US media context, many of the anchors who reported nonstop on the queen's death and the plans for her state funeral had spent time in Britain. They knew that Britons were not trapped in the sixteenth century but living in the twenty-first. They were a modern nation with, particularly at that time of political and industrial turmoil, a lot going on, but those issues were not talked about, whereas for two weeks the queen's life, impact, and legacy were reviewed ad nauseam.

I want to end with a nod to our November roundtable discussion and a comment from a member of the audience who noted that although we had all had a good laugh that morning, it should be remembered that the queen's passing was felt seriously by many people and that the reaction to the queen's passing was a significant event in British cultural history that we should seek to engage with and understand. I do not discount either of those statements, but what to me seems most significant is that this cultural event, particularly but not exclusively for its American media consumers, was packaged and constructed to present a picture of the British nation that was not only largely false but also actively patriarchal, atavistic and, frankly, feudal. The pretense that, as inflation, the lingering impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and political and economic chaos swirled around the democratic nations of the United Kingdom, its citizens were paralyzed in mourning for the death by natural causes of a ninety-six-year-old woman and that their mourning and the archaic and pageant-filled ways in which they (or more accurately the state to which they paid taxes) performed that mourning was the only newsworthy thing about them, suggested a willful ignorance on the part of the American media of the reality of life in modern Britain.

Before the pandemic, American tourism to Britain averaged more than 2.5 million visitors per year, with the majority paying visits to Buckingham Palace to watch the changing of the guards and possibly traveling down to Windsor or spending an afternoon touring one of the dozens of other royal homes. One journalist asked me whether the tourism revenue generated by the royal family offset their high cost of the British taxpayer—a claim repeatedly made in defense of the perpetuation of the British monarchy. But revenue earned by tourist shops hawking Elizabeth II biscuit tins is not automatically redistributed to the broader citizenry who foot the bill for the royal family, and the global media focus on the royals perpetuates a myth of a fairy-tale Britain at the expense of a deeper understanding of the country and its people—not to mention the people of the former empire—by those beyond Britain's borders.