The forecasts for the world and the UK economy reported in this Review are produced using the National Institute's global econometric model, NiGEM. NiGEM has been in use at NIESR for forecasting and policy analysis since 1987, and is also used by a group of more than 40 model subscribers, mainly in the policy community. Most countries in the OECD are modelled separately,Footnote 1 and there are also separate models for China, India, Russia, Brazil, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, South Africa, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Bulgaria. The rest of the world is modelled through regional blocks so that the model is global in scope. All models contain the determinants of domestic demand, export and import volumes, prices, current accounts and net assets. Output is tied down in the long run by factor inputs and technical progress interacting through production functions, but is driven by demand in the short to medium term. Economies are linked through trade, competitiveness and financial markets and are fully simultaneous. Further details on NiGEM are available on http://nimodel.niesr.ac.uk/.

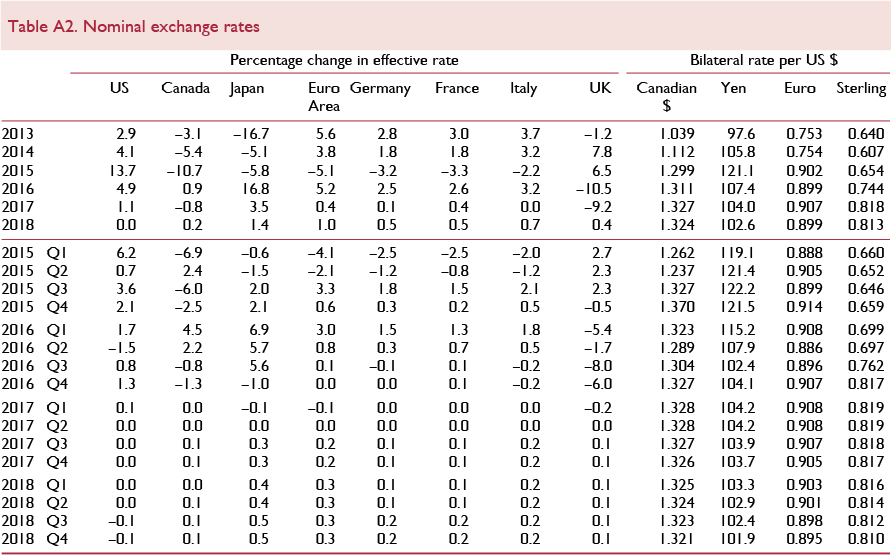

The key interest rate and exchange rate assumptions underlying our current forecast are shown in tables A1–A2. Our short-term interest rate assumptions are generally based on current financial market expectations, as implied by the rates of return on treasury bills and government bonds of different maturities. Long-term interest rate assumptions are consistent with forward estimates of short-term interest rates, allowing for a country-specific term premium. Where term premia do exist, we assume they gradually diminish over time, such that long-term interest rates in the long run are simply the forward convolution of short-term interest rates. Policy rates in major advanced economies are expected to remain at low levels, at least in the rest of this year and throughout 2017.

The Reserve Bank of Australia and the central bank of New Zealand lowered their benchmark interest rates by a further 50 basis points in two steps in 2016, after cutting them by 50 and 100 basis points correspondingly in 2015. The People's Bank of China and the Indian central bank both reduced their interest rates throughout 2015 by a total of 125 basis points each. While the People's Bank of China has kept them unchanged since, the Indian central bank lowered its benchmark rate further by 50 basis points in two rounds in 2016. After reducing its policy rate by 100 basis points in four steps between August 2014 and June 2015, the Bank of Korea cut it again by 25 basis points in June 2016. Indonesia's central bank reduced its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points in February 2015, for the first time since 2012, and then lowered it again by 100 basis points in 2016 in four steps. However, after replacing the official discount interest rate with a new 7-day reverse repurchase rate in August 2016, the interest rates were lowered in two further steps, by 25 basis points in each case. The Central Bank of Turkey has left its policy rate unchanged at 7.5 per cent since February last year, following a spell of reductions around the middle of 2014, where the interest rates were reduced by a cumulative 250 basis points. Throughout 2014 and 2015, the Romanian Central Bank reduced its benchmark interest rate by a total of 225 basis points in nine steps and has kept it unchanged since. The National Bank of Hungary has brought its benchmark interest rates down by 120 basis points over eight rounds since the beginning of 2015. The central banks of Norway and Poland have lowered their policy rates by 50 basis points each in 2015, to 0.75 and 1.5 per cent respectively. The central bank of Norway cut its benchmark rate further by 25 basis points in March 2016, while the central bank of Poland has left them unchanged. Over the course of last year, the Swedish Riksbank cut its policy rate by 35 basis points in three rounds and lowered it again, by 15 basis points, in the beginning of this year. At the time of writing, the Riksbank's policy rate stands at −0.5 per cent. At the turn of 2015 the Swiss National Bank cut its benchmark rate by 25 basis points to −0.75 per cent, while the Central Bank of Denmark reduced them by 15 basis points to just 0.05 per cent. Both central banks have left their main policy rate unchanged since. After reducing the interest rate by a cumulative 600 basis points, to 11 per cent over five stages in the first seven months of 2015, the Central Bank of Russia lowered it again in two steps by a total of 100 basis points in June and September 2016. The Bank of Canada has kept its benchmark interest rate unchanged, at 0.5 per cent, after lowering it by 50 basis points over two rounds last year. These were the Bank of Canada's first cuts in nominal interest rates since April 2009.

In contrast, the Central Bank of Brazil and the South African Reserve Bank both increased interest rates in response to inflationary and financial market pressures in 2015. The South African Reserve Bank increased its benchmark rate by 50 basis points in two rounds last year and the Central Bank of Brazil has raised its interest rate by 250 basis points to 14.25 per cent, in a series of steps over the course of 2015. While the Central Bank of Brazil, following easing inflationary pressures and the election of a new government, cut its interest rate by 25 basis points in October 2016 – for the first time since 2012 – the South African Reserve Bank increased theirs further by 75 basis points in two rounds this year. To stem downward pressure on the Peso following a rise in the federal funds rate in the US, the central bank of Mexico has increased its interest rate by 175 basis points in four rounds since December 2015. These were the first increases since August 2008.Footnote 2

In December 2016, the Federal Reserve raised the target range for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points to 0.25–0.50 per cent. This action, agreed unanimously by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), was taken seven years after the target range had been lowered to near zero, and six and a half years after the end of the US recession of December 2007–June 2009. The statement accompanying the Fed's decision emphasised that monetary conditions remained accommodative after the increase; that the timing and size of future adjustments would depend on its assessment of actual and expected economic conditions relative to its objectives, and that it expected that only gradual increases in the rate would be warranted. This message has been reiterated by the FOMC at subsequent meetings. Indeed these assessments have led it to conclude that further interest rates were not warranted in meetings up to and including September of this year. The median projection of the FOMC at its September meeting was that it would be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points by the end of 2016, presumably in December.

The expectation of the first rate change of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England is based on our view of how the economy will evolve over the next few years. As the UK chapter in this Review discusses, we expect the UK economy to experience a marked slowdown as a consequence of the vote to leave the EU.Footnote 3 At their August meeting, to mitigate the expected downturn, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England introduced a policy package which included a reduction in Bank Rate by 25 basis points to 0.25 per cent, the purchase of £60 billion of government bonds and a programme of £10 billion of purchases of sterling denominated corporate bonds. In line with market expectations, Bank Rate is assumed to remain at 0.25 per cent until the end of 2017. At the time of writing, financial markets expect the MPC first to raise rates back towards 50 basis points in the summer of 2020, and to 70 basis points in the second half of 2021. We think an earlier move is more likely, with a rise to 50 basis points in May 2019, after the completion of the UK's two-year negotiated withdrawal from the EU. Bank Rate is expected to reach 2 per cent by the first quarter of 2021, this being the point at which the MPC is assumed to stop reinvesting the proceeds from maturing gilts it currently holds, allowing the Bank of England's balance sheet to shrink ‘naturally’.

The central banks of the Euro Area (ECB) and Japan (BoJ) continue to expand their balance sheets. The ‘expanded asset purchase programme’ which began in March 2015 was expanded further in March this year. The original package envisaged combined purchases of assets amounting to €60 billion a month until at least September 2016. In the latest package, beginning in April 2016, monthly purchases increased to €80 billion and “run until end-March 2017, or beyond, if necessary, and in any case until the Governing Council sees a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation consistent with its inflation aim”. Recently the ECB acknowledged that the constraints that it had placed on its asset purchase programme (see Box B in this Review) were threatening to bind. In response the ECB announced that it would undertake an evaluation of the options available to ensure the smooth implementation of the purchase programme in the environment of interest rates much lower than when the parameters were originally set.

In October 2014, the BoJ surprised financial markets by announcing that it would expand its asset purchase programme by about 30 per cent. The programme envisaged an increment of about ¥80 trillion added to the monetary base annually, up from an existing ¥60–70 trillion. First in December 2015 and then in September 2016, the BoJ announced further modifications of its programme of quantitative and qualitative easing (QQE). The latest round of changes was motivated by the Bank's concern that negative interest rates, together with its asset purchase programme, via a flattening of the yield curve, posed risks to bank profitability and the viability of pension funds and thus to financial stability and the economy. The Bank therefore announced that the QQE framework would be supplemented by “yield curve control”: the Bank would regulate its asset purchases to target the 10-year government bond yield, initially at zero, so that it would control long-term as well as short-term interest rates.

Figure A1 illustrates the recent movement in, and our projections for, 10-year government bond yields in the US, Euro Area, the UK and Japan. Convergence in Euro Area bond yields towards those in the US, observed since the start of 2013, reversed at the beginning of 2014. Since February 2014, the margin between Euro Area and US bond yields started to widen, reaching a maximum of about 150 basis points (in absolute terms) at the beginning of March 2015. Since then the wedge has narrowed, remaining at around 100 basis points till the end of July 2016, after which point it has increased marginally and stayed at about 120 basis points. In the second half of 2014 a wedge has opened between the US and UK government bond yields, which fluctuated between 20–30 basis points throughout last year. Since the beginning of 2016, the margin started to widen again, reaching a peak of 80 basis points in August and then marginally narrowing to about 70 basis points in October. Looking at the levels of 10-year sovereign bond yields in 2016, these have increased slightly since the end of July in the US, the Euro Area, the UK and Japan – by about 20 basis points in the UK, US and Japan, and by about 15 basis points in the Euro Area. Expectations for bond yields for 2017, compared with expectations formed just three months ago, are largely unchanged for the US and Japan, and are lower by about 15–25 basis points in the Euro Area and the UK.

Figure A1. 10-year government bond yields

Sovereign risks in the Euro Area have been a major macroeconomic issue for the global economy and financial markets over the past five years. Figure A2 depicts the spread between 10-year government bond yields of Spain, Italy, Portugal, Ireland and Greece over Germany's. The final agreement on Private Sector Involvement in the Greek government debt restructuring in February 2012 and the potential for Outright Money Transactions (OMT) announced by the ECB in August 2012 brought some relief to bond yields in these vulnerable economies. Sovereign spreads have remained stable, in most cases, from late July 2014, the most notable exception being a marked widening of Greek spreads. For Greece this reflected initial uncertainty over the fiscal stance and probability of debt repayment following the formation of a government dominated by a political party elected on an ‘anti-austerity’ manifesto in January 2015. The risk of Greece leaving the Euro Area returned to the fore, as a deal on a third bailout for Greece appeared unlikely. In the summer of 2015 a lack of liquidity led to a three-week closure of the domestic banking system, with withdrawal limits imposed upon Greeks’ bank accounts and the imposition of controls on external payments. The dangers relating to the financial difficulties of Greece and the policy programme being negotiated with its European partners subsequently receded. In mid-August last year, it was confirmed that negotiators had reached agreement in principle on a 3-year fiscal and structural reform programme to be supported by €86 billion of financing from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Disbursements (including cash and cashless) totalling €28.9 billion were made by the ESM between August last year and October 2016. However, sovereign spreads remain elevated due to issues around long-term debt sustainability.

Figure A2. Spreads over 10-year German government bond yields

In Portugal sovereign spreads started to widen from the end of 2015, and throughout 2016 have been around the levels last seen at the beginning of 2014. A combination of factors, including the ‘anti-austerity’ stance of the new Socialist government, a surprise decision by the Portuguese central bank to impose losses on bank bonds held by international investors, a risk of a credit-rating downgrade that could result in the exclusion of government bonds from the ECB's assetbuying programme and weakness in the banking system combined with a high level of government debt (around 128 per cent of GDP) led to Portuguese bonds being the worst performers in the Euro Area (after Greece). In our current forecast we have assumed spreads over German bond yields continue to narrow in all Euro Area countries, and that this process resumes both in Greece and Portugal.

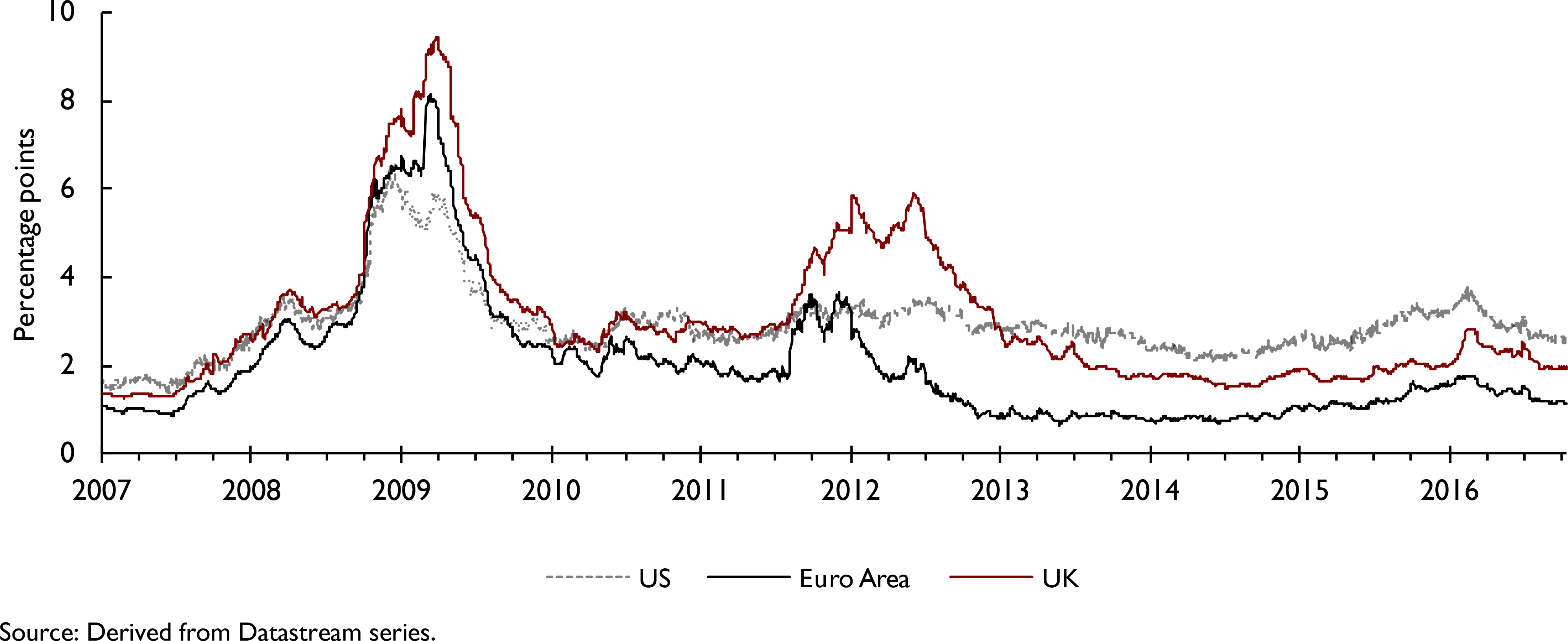

Figure A3 reports the spread of corporate bond yields over government bond yields in the US, UK and Euro Area. This acts as a proxy for the margin between private sector and ‘risk-free’ borrowing costs. Private sector borrowing costs have risen more or less in line with the observed rise in government bond yields from the second half of 2013 till the second half of 2015, illustrated by the stability of these spreads in the US, Euro Area and the UK. Reflecting tightening financial conditions, corporate bond spreads widened at the turn of this year, but subsequently have come down somewhat and have been relatively stable recently, barring the jump observed around the period of the UK's decision to leave the EU. Our forecast assumption for corporate spreads is that they gradually converge towards their long-term equilibrium level.

Figure A3. Corporate bond spreads. Spread between BAA corporate and 10-year government bond yields

Nominal exchange rates against the US dollar are generally assumed to remain constant at the rate prevailing on 13 October 2016 until the end of June 2017. After that, they follow a backward-looking uncovered-interest parity condition, based on interest rate differentials relative to the US. Figure A4 plots the recent history as well as our forecast of the effective exchange rate indices for Brazil, Canada, the Euro Area, Japan, UK, Russia and the US. In foreign exchange markets, the largest movement in the past three months has been further depreciation of sterling against other major currencies – by about 8 per cent in trade-weighted terms, leaving trade-weighted sterling around 14 per cent below the level at the end of 2015. The yen has remained the strongest currency among the advanced economies, rising by about 2 per cent against the US dollar since late July, leaving the yen's trade-weighted value in the third quarter about 25 per cent above its trough in the second quarter of 2015. In effective terms, the US dollar and the Euro are little changed since late July. Among the emerging market currencies, the Chinese renminbi has depreciated slightly further against the US dollar and, in trade-weighted terms, the Brazilian, Indian and Russian currencies have all appreciated against the US dollar. Since the second quarter the trade-weighted value of the Brazilian real and Russian rouble have increased by about 9 and 3 per cent respectively, mainly reflecting political developments in the former and oil price developments in the latter.

Figure A4. Effective exchange rates

Our oil price assumptions for the short term are based on those of the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), published in October 2016, and updated with daily spot price data available up to 14 October 2016. The EIA use information from forward markets as well as an evaluation of supply conditions, and these are illustrated in figure A5. Oil prices, in US dollar terms, have risen from about $45 a barrel in July to about $52 a barrel in late September, still less than half the level of prices that prevailed in 2011–13. The rise in prices seems due to the announcement in late September of an informal agreement among OPEC countries to reduce production to 32.5–33.0 million barrels a day from the recent level of about 33.3 mbd. However, details of the agreement remain to be decided at the next formal OPEC meeting in late November. Projections from the EIA suggest about 25 per cent increase in prices towards the end of 2017. Current expectations about the position of oil prices at the end of this year have increased by about 7 per cent, compared to the expectations formed just three months ago. This still leaves oil prices about $60 lower than their nominal level in mid-2014. Oil prices are expected to be about $49 and $56 a barrel by the end of 2016 and 2017, respectively.

Figure A5. Oil prices

Our equity price assumptions for the US reflect the expected return on capital. Other equity markets are assumed to move in line with the US market, but are adjusted for different exchange rate movements and shifts in country-specific equity risk premia. Figure A6 illustrates the key equity price assumptions underlying our current forecast. Stock market performance since the second quarter of 2016 has been mixed, with the largest increase in the UK (in terms of the FTSE-100) attributed to the effect of a depreciation of sterling on the profit margins of large corporations that earn most of their revenues in foreign currency. The steepest declines have been in Greece and Italy, most likely reflecting concerns of debt sustainability in the former and the implications for bank profits from low interest rates in weak banking sector in the latter.

Figure A6. Share prices

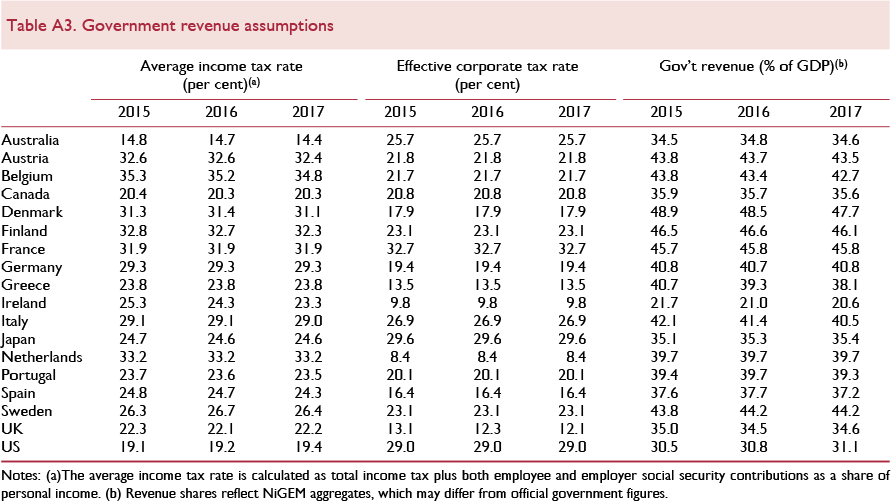

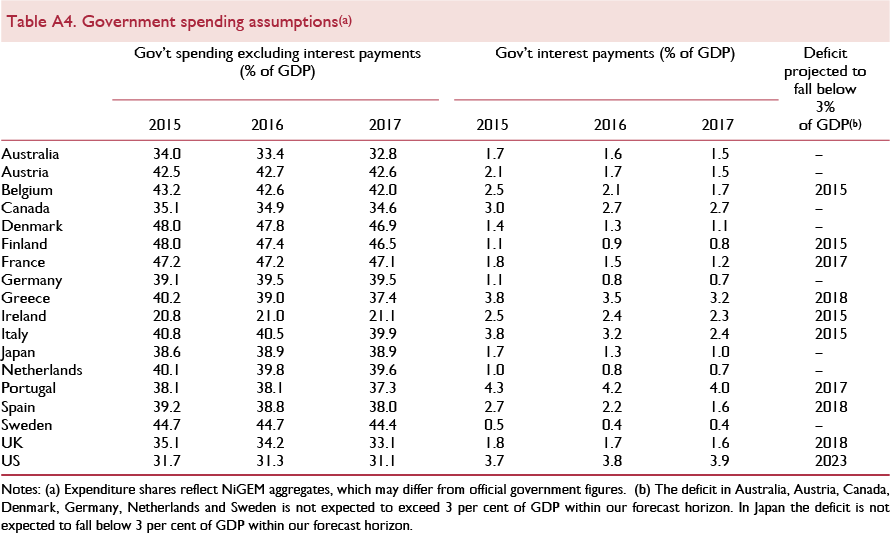

Fiscal policy assumptions for 2016 follow announced policies as of 7 October 2016. Average personal sector tax rates and effective corporate tax rate assumptions underlying the projections are reported in table A3, while table A4 lists assumptions for government spending. Government spending is expected to continue to decline as a share of GDP between 2017 and 2016 in the majority of Euro Area countries reported in the table. Pressure continues to mount for a loosening of fiscal policy to support demand and indeed the decision by the European Commission in July not to recommend that fines should be levied on Portugal and Spain for failing to take effective action to reduce their deficits is a sign of an easing of the discipline involved in the Stability and Growth Pact. Infrastructure investment, which supports both demand in the near term and potential growth in the longer term is where the calls for spending should be particularly focused (IMF, 2016 and OECD, 2016). A policy loosening relative to our current assumptions poses an upside risk to the short-term outlook in Europe. For a discussion of fiscal multipliers and the impact of fiscal policy on the macroeconomy based on NiGEM simulations, see Reference Barrell, Holland and HurstBarrell et al. (2012).