Introduction

Theft and how to catch a thief were undoubtedly pressing problems in antiquity, above all when the identity of the guilty party was unknown. In those cases, people had to resort to other means that would allow them to identify, catch, and punish wrongdoers.Footnote 1 In such precarious situations, which would certainly have given rise to an array of emotions such as insecurity, anxiety, frustration, anger and desperation, victims of theft often turned to the divine for assistance.

One way of doing so was by writing a curse tablet. In the provinces of the Roman West, the use and diffusion of curse tablets have been linked to the so-called process of Romanization. As magical-religious artefacts that were in use for over a millennium in a wide range of geographical contexts, however, curse tablets must also be conceived of as representing a ‘living’ cultural practice, whose biography deserves our attention. In a study of domestic magical practices in modernity, Owen Davies correctly points out that ‘artefacts have life histories that need to be considered and contextualised in order to better understand their meaning, and the societies that employed them, at any point in time’.Footnote 2 And curse tablets are no exception: in fact, this magical-religious technology was adopted at different levels of provincial societies and then adapted to become something new and unique.Footnote 3

Scholarly debate about curse tablets against thieves can be traced back to 1904, when Auguste Audollent first proposed his still influential taxonomy for curses, which organizes them – when possible – by the nature of their content.Footnote 4 Among Audollent's categories, that which contained curses targeting thieves and slanderers (defixiones in fures, calumniatores et maledicos conversae) was the smallest, with only twenty known examples, and of these, only five hailed from the Latin West. But this picture had drastically changed by the end of the twentieth century in light of a series of very important archaeological discoveries. As of today, we know of more than a hundred such texts.

As the prominence of these curses has come into view, they have also come under greater scholarly scrutiny and the very validity of Audollent's label defixiones in fures (‘curses against thieves’) has been questioned. In fact, a good deal of ink has been spilled over whether or not we should call these inscriptions curses at all. It has been argued that these texts were displayed publicly and sometimes contained invocations that recalled the conventions of prayers and vows. Due to these observations, the execratory nature of these inscriptions has been seriously called into question. In various studies, Henk Versnel has proposed a new categorization for these tablets, which he has dubbed ‘prayers for justice’ and which he defines as ‘pleas addressed to a god or gods to punish a (mostly unknown) person who has wronged the author (by theft, slander, false accusations or magical action), often with the additional request to redress the harm suffered by the author’.Footnote 5

Among the features that distinguish prayers for justice from ‘authentic’ curse tablets, Versnel includes the following:

1. the principal states his or her name; 2. some grounds for the appeal are offered; this statement may be reduced to a single word, or may be enlarged upon; 3. the principal requests that the act be excused or that he be spared the possible adverse effects; 4. gods other that the usual chtonic deities are often invoked; 5. these gods…may be awarded a flattering epithet…or a superior title…; 6. words expressing supplication…are employed as well as direct, personal invocations of the deity; 7. use of terms and names referring to (in)justice and punishment.Footnote 6

But if Versnel identified ‘pure’ curse tablets on the one hand and prayers for justice on the other, he also acknowledged the existence of ‘border-area cases’ in which the features of each category are mixed together.Footnote 7 The high number of such hybrid cases demonstrates just how difficult it can be to draw neat lines between the two categories.

Versnel's proposal has attracted a good deal of attention and several scholars have pushed back on different aspects of his theory. Among them, Amina Kropp has taken issue with the argument about ‘humble sounding language’, which Versnel sees as an important feature of prayers for justice. In Kropp's view, the language used by the authors of these texts should be understood a bit differently, as a ‘protective strategy’ in the face of a great power.Footnote 8 Daniel Ogden, for his part, has taken issue with what Versnel identified as a preference for gods other than the usual chthonic deities, since in these texts we also find the invocation of infernal gods, such as Mercury or Demeter.Footnote 9 But the most critical and sustained attack on Versnel has come from Martin Dreher, who has completely rejected the ‘prayers for justice’ theory.Footnote 10 In brief, he argues that Versnel's category really just maps onto Audollent's defixiones in fures. For Dreher, then, the apparent differences between curses against thieves and prayers for justice are non-existent, especially since ‘a large part of the evidence consists of mixed cases’.Footnote 11 Interestingly, Dreher concludes by introducing yet another label into the scholarly discourse, arguing that we should actually call these texts ‘criminal curses’.Footnote 12

As a scholar, I readily accept that these taxonomies can be useful tools for helping us understand and analyse specific phenomenon. That said, I worry that the issue has been taken too far. Instead, and in view of how curse tablets functioned as a technology that evolved over time and space (being adapted by the societies that employed them), I suggest that we try to understand these inscriptions from a more emic perspective.Footnote 13 For that reason, and although Versnel has moved the debate forward more than any other scholar, I must admit that I am not totally convinced. While I am happy to accept the general definition of ‘prayers for justice’ as curses that seek vengeance and punishment for a crime, I am uncomfortable with drawing any sort of rigid line between curse tablets and prayers for justice, as Daniela Urbanová, for instance, does.Footnote 14 At least, I feel this way about the curse tablets from the Roman West, which my research has focused on.

From my point of view, the material characteristics of the so-called ‘prayers for justice’, their archaeological contexts, and the emotions and feelings reflected within these texts do not justify such a radical differentiation from the rest of curse tablets.Footnote 15 At root, they are all a method for mortals to communicate with the divine in a candid and unfiltered way. These texts provide evidence for the experimental ways in which individuals called upon the gods with the hope of remedying their personal misfortune. To establish a hard border between curse tablets and prayers for justice harks back to the great dichotomy between religion and magic that recent scholarship has done so much to dismantle. As Richard Gordon, in particular, has argued, ‘magic’ would be more fruitfully understood as a subsystem of ‘religion’.Footnote 16 What made magic different from other religious practices was the fact that it was not institutionalized and hence not sanctioned by the Roman state. But, as Sarah Veale has shown in an article on the curse tablets deposited in the sanctuary of Isis and Magna Mater in Mainz, this does not mean that the practice was not normalized within certain contexts.Footnote 17

Catching a thief east and west: an overview at the epigraphic and literary records

At present, there are fourteen known Greek curses written against thieves (see Table 1), half of which come from the sanctuary of Demeter on Cnidus and are dated between the second and first centuries bce.Footnote 18 The majority of these tablets are severely damaged, to the point that only one of them is fully preserved (DT 1). Nevertheless, and according to Charles T. Newton, who directed the relevant excavations, these inscriptions ‘were probably suspended on walls, as they are pierced with holes at the corners’.Footnote 19 Despite the fact that in the published drawings most of the pieces are missing their original edges, and only one of them (no. 1 in Table 1) has a hole in the centre of the upper edge (not in the corners), Newton's observation has led many scholars to conclude that these tablets were displayed in the temple. Furthermore, by analogy, they have gone on to suggest that all curse tablets against thieves were probably displayed in a similar manner.Footnote 20 Such an inference, however, is unwarranted since Newton himself claims that, at the moment of discovery at the sanctuary of Demeter, he ‘found in several places portions of thin sheets of lead, broken and doubled up. On being unrolled, these sheets proved to be tablets inscribed with imprecations.’Footnote 21 This means that, while at least one tablet could have been displayed for a limited amount of time (the perforation of tablet number 1 leaves this possibility open), all Cnidian tablets were eventually rolled up or folded before being deposited in the sanctuary, as is the case with the vast majority of known Latin curses against thieves.Footnote 22

Table 1 Greek curse tablets against thieves known to date

Concerning the rest of the Greek evidence, while two other bronze curse tablets were pierced for display (nos. 11–12 in Table 1), two were left ‘open’ (nos. 10 and 14, deposited in a pit of a private house and a tomb respectively), and another was rolled (no. 9, discovered at a well in the Athenian Agora), while the rest were too fragmentary to analyse fully. Accordingly, the supposed exhibition of the Greek curse tablets against thieves, which is pointed to as a defining aspect of these pieces, should not be taken for granted.

When it comes to the content, interestingly, most of these texts contain at least one of the following features: the name of the author, the transference of the stolen object to the gods, or the transference of the thief him- or herself. One especially well-preserved tablet from Cnidus (no. 1) was written by a woman named Artemis, who not only beseeches Demeter to help return several articles of clothing, but also asks that the criminal, racked with a fever, publicly declares himself or herself guilty.Footnote 23 Versnel has compared this type of public confession to the so-called ‘confession stelae’ from Lydia and Phrygia, dated to the second and third centuries ce, in which authors admit to the crimes that they have committed (theft, impiety, and so forth) in order to be publicly reconciled with the god.Footnote 24

In addition to these stelae, there are other telling parallels in the Greek Magical Papyri. PGM V, which has been dated to the third or fourth century ce, contains two recipes for catching a thief. The first recipe tells the reader to paint an eye on a wall and to fashion a hammer from a piece of gallows’ wood; next, the painted eye is to be struck with the hammer, while reciting the following formula: ‘Hand over the thief who stole it. As long as I strike the eye with this hammer, let the eye of the thief be struck and let it swell up until it betrays him.’Footnote 25 The second recipe recommends offering cheese and wheat to those who are suspected of committing the crime, while saying ‘Master IAO, light-bearer, I hand over the thief whom I see.’ At this point the papyrus adds: ‘If one of them does not swallow what was given to him, he is the thief.’Footnote 26

Both of these recipes provide a means for forcing the guilty party to publicly reveal his or her identity. As we have just seen, this topos of the public confession is present in both the PGM and the texts from Asia Minor. This practice is not found, however, in curse tablets from North Africa or the other Greek-speaking portions of the Roman Empire. We are probably confronted here with two parallel but distinct solutions that arose organically within a local context in an attempt to solve the same pressing problem: how to catch a thief.

Latin curse tablets addressing a theft form one of the best-attested genres of curses known from the Roman West. Of the 106 known examples, it is worth noting the high concentration of such texts in Britannia, since 86 of the tablets come from this province alone. The remaining 20 were found in Hispania, Gallia, Pannonia, Raetia, and Italy. The outsized prominence of British curse tablets against thieves is largely due to the extraordinary discoveries in the sanctuaries of Sulis Minerva in Bath and Mercury in Uley.Footnote 27 An interesting question is whether this can be thought of correctly as a British phenomenon. While these two sanctuaries have large numbers of tablets written in response to a theft,Footnote 28 it is worth noting that curses against thieves are found more broadly throughout the island, with twenty-four additional examples: a number that is still higher than that for any other province.

With or without the finds from the sanctuaries at Aquae Sulis and Uley, the curses against thieves from Britannia become even more relevant when we remember that we do not know the reason why most curses from the island were written, since the majority are extremely fragmentary or simply provide a list of names. At this point, we must ask whether the practice of writing curse tablets was adopted in this province as a specific technology that responded to the problem of theft. The most loquacious evidence would support such a conclusion.

The abundance of similar formulae found in the curses against thieves from Britannia is so great that we can suppose that there was shared cultural knowledge about how they worked and what they could do. This knowledge would have been established and spread among the local population, members of which, importantly, produced their own texts. Thus, of the 130 curse tablets from Bath, palaeographic analysis reveals that only 2 were written by the same hand.Footnote 29 This fact strongly suggests that many individuals at least knew the ABCs of cursing. On this point, a curse from Lidgate that was preserved in full provides a telling example. It reads: ‘the rings which have been lost, whether woman or man, whether free or slave…’.Footnote 30 As Roger Tomlin, editor of the text, has rightly noted, ‘except for [a]nuli, the text is nothing but formulas, as if stolen property could be recovered simply by copying out disconnected but familiar phrases like a magic spell’.Footnote 31 Despite the striking continuity between these texts, it is easy to overlook subtle yet important variations within this corpus. As we will see, evidence suggests that there was common knowledge about casting such curses but that it was far from routinized. It is to these subtle differences that I now want to turn.

Like the texts from Cnidus, the Latin curses against thieves often contain the three features mentioned above: the author's name, the handing over of the thief to the god, or the transference of the stolen item to the god. Here, I will only discuss the last of these, paying special attention to those tablets in which the transference involves only a fraction of the stolen item.

Trading with the gods? Giving what you no longer have

Of the 100 known curses against thieves, 20 (one from Hispania, the rest from Britain) document the transference of stolen property to the gods. Most of these inscriptions were placed in sacred spaces, a location that would have offered the authors of these texts inspiration and models for how to communicate with the gods, as Roger Tomlin suggested in his edition of the Bath tablets.Footnote 32

Just as with votives, which give something to the god in return for divine favour or assistance, most of these curse tablets explicitly transfer ownership of the stolen object through the use of the verb ‘to give’ (do or dono), usually in the present indicative. And while giving away something that you no longer possess may appear impossible, we must remember that, according to Roman law, someone who suffered a theft still remained the rightful owner of the stolen object and hence retained the right to give it away.

In the past, scholars have been right to point out one result of the transaction in these texts: by giving away an object to the god, the author in essence transformed a simple act of petty theft into a sacrilege.Footnote 33 Accordingly, a thief would not only be guilty of larceny, but would also be marked with impiety. And instead of having wronged another human being, he or she would have offended someone much more powerful. This type of transfer of property could undoubtedly have been thought of as a way to further motivate a deity to intervene and hunt down the wrongdoer. Having entered a sort of reciprocal relationship with the author of the curse, the deity was now also acting in his or her own interests.

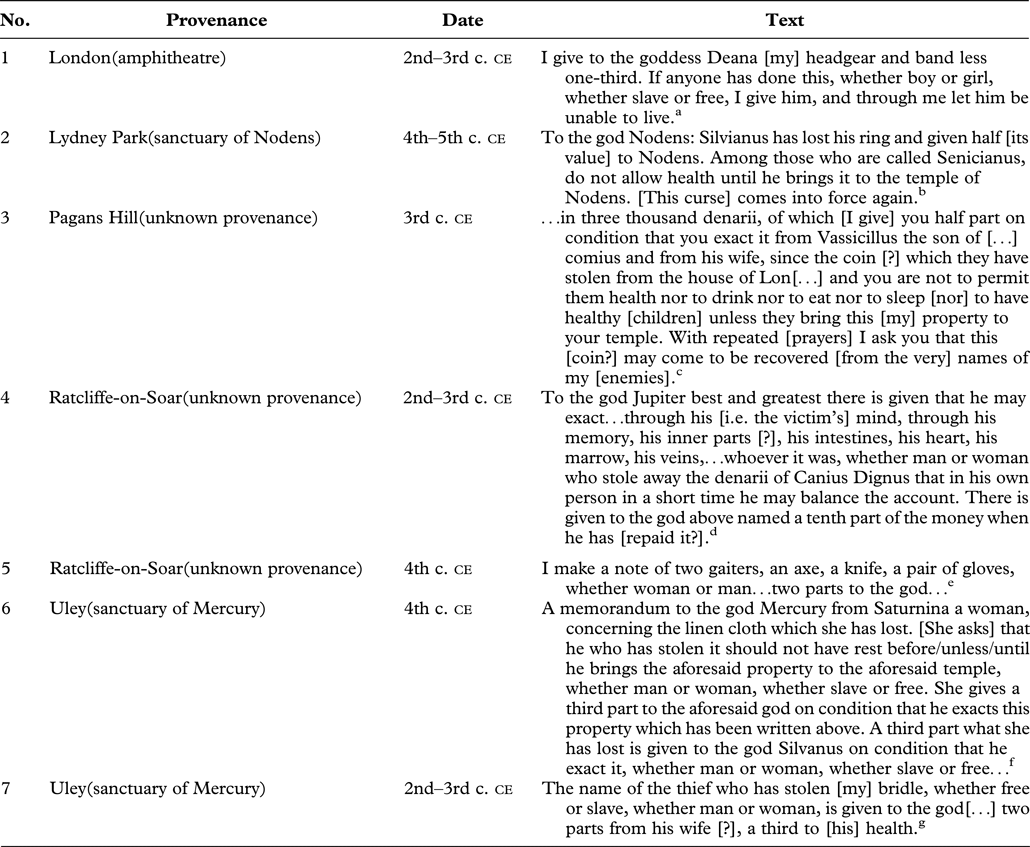

But, as alluded to above, the author of the curse did not always give the deity full ownership of the stolen object. In fact, in at least seven examples (listed in Table 2), the god is only granted a fraction of the stolen object. All of these texts come from Britannia and can be dated between the second and fifth centuries ce. Four were discovered in sanctuaries or sacred spaces, while three were found by metal-detector users and hence there is no accurate archaeological data about their findspot.Footnote 34 A frequent feature of these pieces is the request that the god punish the thief. The exact punishment desired is variable, ranging from ‘not to have rest’ (no. 6) or ‘do not allow health’ (no. 2) to impeding his or her basic vitals (no. 3). In all of these cases, the punishments were to be in effect until the guilty party deposited the stolen goods in the temple. That said, when the tablet calls for the thief's life (no. 1) or the thief him- or herself is offered to the god (nos. 4 and 7), the author of the curse does not establish a timeframe for the punishment, since it is absolute and definitive.Footnote 35

Table 2 Curse tablets against thieves in which the god is only granted a fraction of the stolen object

a Edited and translated by R. S. O. Tomlin, ‘Inscriptions’, Britannia 34 (2003), 362. See also AE 2003, 1021 = SD 343.

b Translation extracted from RIB I 306. See also DT 106 = SD 205.

c Edited and translated by R. S. O. Tomlin, ‘Inscriptions’, Britannia 15 (1984), 336. See also AE 1984, 623 = SD 443.

d Translated by E. G. Turner, ‘A Curse Tablet from Nottinghamshire’, JRS 53 (1963), 123, with a slight modification. See also AE 1964, 168 = SD 349.

e Edited and translated by R. S. O. Tomlin., ‘A Roman Inscribed Tablet from Red Hill, Ratcliffe on Soar (Nottinghamshire)’, Antiquaries Journal 84 (2004), 364–52; see also AE 2004, 856 = SD 351.

f Translated by R. S. O. Tomlin, ‘The Inscribed Tablets: An Interim Report’, in Woodward and Leach (n. 27), 121. Note that the theonym Mercury was written over Mars Silvanus. On this curse tablet, see also AE 1979, 384 = SD 356.

g Edited and translated by R. S. O. Tomlin, ‘Inscriptions’, Britannia 15 (1984), 126. See also AE 1989, 486 = SD 359.

As mentioned before, a common feature of these texts is that the gods are granted only a fraction of the stolen object. But how could the author of the text give the deity half of a ring, as Silvianus does with the god Nodens (no. 2)? Leaving aside the complications involved in splitting up such an object, I want to stress that in such instances the author conceives of him- or herself as a sort of equal, or better, partner of the god. If the stolen property is recovered, the victim of the theft and the deity share its value. In the simplest of scenarios, an object would be split equally. Thus, in a fourth-century curse from Uley (no. 6), Saturnina ‘a woman’ gives a third of her stolen cloth to Mercury and another third to Silvanus, keeping for herself the last third. Something similar happens in a third-century curse tablet from Pagans Hill (no. 3), where the practitioner offers half of the stolen money to the deity, presumably keeping the rest for him- or herself. But splitting the value of the stolen object 50–50 was not always the case. In a second- or third-century curse from London (no. 1), the practitioner generously gives two-thirds of the stolen items to the goddess Diana (keeping the rest for him- or herself), while there is a fourth-century curse from Ratcliffe-on-Soar (no. 4) in which the author only gives the god one-tenth of the stolen denarii, keeping the lion's share for himself.

This type of text, which almost appears to be contractual, requires us to question the type of relationship established between humans and gods, which is laid out in terms that establish a relationship between equal parties; furthermore, we must examine more generally the complex nature of this subgroup of curses against thieves.Footnote 36 These texts contain not only the standard features of a curse (whose objective is the discovery and punishment of the victim) but also elements of a contractual nature, which are used in an attempt to establish a sort of agreement with the gods.

At this point we must consider how we should understand and what we should call these types of agreements. Despite the temptation, we should not call them contracts plain and simple, since obviously the gods do not consent to the agreement (in actual contracts both parties must give their consent). Several scholars have compared these tablets to a vow (votum), which is an attractive suggestion, though not a perfect match, since, as Versnel notes, the stolen object ‘is ceded, not vowed’ to the deity.Footnote 37 So while we cannot speak of a votum exactly, it is possible, as Tomlin has suggested for the tablets from Bath, that the votum served as a model for the practitioners who wrote these curses. Given that the curse tablets were deposited in sacred spaces that were filled with votive offerings, is it possible that these texts constitute a new take on the more traditional vow?

As is well known, the vow is made of two parts: a public pronouncing of vows (the nuncupatio, in which the practitioner spells out with precision his or her request and promise) and the fulfilment of the vow (the solutio, in which the practitioner carries out his or her promise and often documents this epigraphically). A fundamental aspect of the vow is the notion of obligatio, a link of a legal character as strong in this realm as it was in the civic world, which, we must remember, pertains to the practitioner and not the promised object. In this scenario, it is only if the gods bring to fruition the request that the practitioner will be obliged to deliver on the promise formulated in the nuncupatio. As John Scheid explains in his fascinating article about the fratres arvales, the vow is based on the logic of reciprocity (commonly referred to as da ut dem), which means that divine intervention is the indispensable prerequisite for the fulfilment of the vow.Footnote 38

If we return to the curse tablets under discussion, we can see that they reflect a somewhat twisted version of the logic of the vow. As noted above, in these texts the practitioners voice a unilateral agreement with the deity, handing over to him or her a fraction of the stolen object that, although they do not have it in their physical possession, nevertheless still belongs to them. While the deity is recognized as a superior being (hence the humble language used), the whole deal is predicated on a civic relationship of a contractual nature; in this respect, it is as if there is an agreement between two equal parties.Footnote 39 Unlike the vow, in this instance the practitioners are no longer subject to the tie of law (obligatio) inherent in this type of relationship. They have already handed over the stolen object to the gods, though it is not physically present. For this reason, it is actually the gods who need to locate the object, if they so wish – or, to put it differently, to feel the sense of obligation. Obviously, in this situation the matter can only be resolved if both parties receive their due share, according to what the practitioner explains in the text.

In this manner and unlike the tablets in which the gods are figured as the new and sole proprietors of the stolen object (and hence they alone would know whether or not the object had been recovered), the texts that we have examined here are different. In this case, handing over only a portion of the stolen object both serves as a mechanism to motivate divine intervention and also demonstrates the practitioner's desire to know whether or not the god has held up his or her end of the bargain.

Conclusions

The writing of curse tablets, which took place over a wide geographic and temporal span, should not be understood as an unchanging static cultural practice. On the contrary, these texts need to be seen in a more organic light and analysed within particular social, historical, and cultural contexts. The sacred context in which most of the curses against thieves were found can help explain some of their most noteworthy features, since the various rituals carried out in these spaces must have exerted influence over practitioners’ thinking, irrespective of whether they were conscious of this influence or not. However, we would be going too far to claim that this influence simply converts them into prayers or votives.

The curses against thieves in which only a fraction of the stolen property is given to the god provide a good example of how these texts synthesize elements from different spheres of life and various discourses (vows, Roman law, defixiones), and constitute, in fact, a new version of an already existing technology; in other words, these curses should not be thought of as something completely new. In these texts, practitioners approach the gods employing some of the conventions of the vow (votum); the rules of this vow, however, are then twisted and paired with legal concepts (such as obligation or ownership) in order to gain divine assistance and also to obtain tangible evidence of the god's help. All of this is at play in these curses, without leaving aside the fundamental purpose of these texts: to curse the thief.