At 11:30 p.m. on August 4, 1964, in Washington, DC, President Lyndon Johnson informed the American public that he had ordered air strikes on North Vietnam in response for the apparent attacks by North Vietnamese patrol boats on US Navy ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. At that moment half a world away, fifty-two navy fighters from the carriers USS Ticonderoga and USS Constellation flew toward patrol-boat bases at Phúc Lợi, Quảng Khê, and Hòn Gai, and the oil storage depot at Vinh. The air strikes, dubbed Operation Pierce Arrow, wrecked half of North Vietnam’s small torpedo-boat flotilla and almost one-fourth of its oil supply, but the attackers did not emerge unscathed. Anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) fire claimed two A-4 Skyhawks, killing Lieutenant Junior Grade Richard Sather and forcing Lieutenant Junior Grade Everett Alvarez to parachute from his stricken aircraft. Alvarez would remain a prisoner of war of the North Vietnamese for eight long years.

At the time of the air strikes, few if any Americans realized that the raids signaled the start of an extended application of air power that would deposit 8 million tons of bombs on the landscape of Southeast Asia between 1964 and 1973. Half of that total fell on South Vietnam, the United States’ ally in the perceived struggle against communist aggression. Roughly 3 million tons fell on Laos and Cambodia, so-called neutrals in the Vietnamese conflict. The remaining million tons landed on North Vietnam, with the bulk of that falling during the Operation Rolling Thunder air campaign of 1965–8.Footnote 1 Despite the enormous amount of ordnance dropped, and the vast displays of technology dropping it, two years after the United States removed its forces from the war, South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia were communist countries.

Did the inability of bombing – and innumerable airlift and reconnaissance sorties – to prevent the fall of South Vietnam demonstrate the limits of air power, or did it reveal that the strategy that relied heavily on air power’s kinetic application to achieve success was fundamentally flawed? From the vantage point of more than a half-century after the bombing began, and more than forty years after the last bomb fell, the answer to both questions remains yes. Yet the two questions are intimately related, and answering them reveals the enormous impact that a political leader can have on the design and implementation of an air strategy, especially in a limited war. Ultimately, the air wars in Vietnam demonstrate both the limits of air power and the limits of a strategy dependent on it when trying to achieve conflicting political goals. The legacies of the air wars in Vietnam remain relevant to political and military leaders grappling with the prospects of applying air power in the twenty-first century.

The reliance on air power to produce success in Vietnam was a classic rendition of the “ends, ways, and means” formula often used for designing strategy. Air power was a key “means” to achieve the desired “ends” – victory – and how American political and military leaders chose to apply that means to achieve victory yielded the air strategy that they followed. Much of the problem in Vietnam, though, was that the definition of “victory” was not a constant. For Johnson, victory meant creating an independent, stable, noncommunist South Vietnam. His successor, President Richard Nixon, pursued a much more limited goal, one that he called “peace with honor” – a euphemism for a South Vietnam that would remain noncommunist for a so-called decent interval, accompanied by the return of American prisoners of war and the end of the United States’ Vietnam involvement.

For American air leaders as well as Johnson, the million tons of bombs dropped on North Vietnamese soil counted far more than those that fell elsewhere in terms of helping to achieve the desired political objectives. Rolling Thunder offered the promise of ending the war independently with air power, while the bombs falling on South Vietnam promised a ground victory that air power had supported. In the end, a victory of any sort that achieved Johnson’s objective of a noncommunist, stable South proved impossible to obtain with American military force. Many air leaders, however, viewed Johnson’s political restrictions as the key reason that air power had failed to achieve independent success during Rolling Thunder. They pointed to the 1972 bombing as an example of what unfettered air power could achieve, and many focused specifically on Nixon’s eleven-day December bombing effort known as Operation Linebacker II. Yet those air commanders who argued that a Linebacker II in 1965 would have “won the war” then failed to see that conditions in 1965 were not the same as those in 1972. Moreover, the objective of Nixon’s aerial onslaught differed significantly from Johnson’s goal of an enduring noncommunist South and was much easier to achieve, particularly given the type of war confronted by American air power in 1972.

The Strategic Foundations of American Air Power

Vietnam proved an especially thorny problem for American air leaders because it did not suit their expectations. After finally achieving the holy grail of service independence in 1947, the air force had become the United States’ first line of defense in the anticipated “general” war against the Soviet Union. That defense was in fact an offense, in which Strategic Air Command’s (SAC) bombers were the centerpiece of the designated strategy. “Massive retaliation,” the guiding principle of President Dwight Eisenhower’s defense policy, promised a tremendous assault with nuclear air power against the Soviet heartland should either the Soviets or a proxy Soviet state launch an attack against the United States or its allies. The concept suffered as a credible option, but the air force ingrained the emphasis on an independent aerial victory in its doctrine. Air leaders realized that air power had failed to win a victory in Korea, but they viewed the limited war there as an anomaly, especially given Eisenhower’s endorsement of massive retaliation. Although they realized that such a limited conflict might recur, they also believed that readiness for general war – a synonym for nuclear combat – sufficed for wars of lesser magnitude.

The air force’s preparation for general war on the eve of Vietnam hearkened back to the prophecy of Billy Mitchell, the teachings of the Air Corps Tactical School, and the perceived effectiveness of strategic bombing in World War II. Mitchell had maintained that air power alone could defeat a nation by paralyzing “vital centers,” which included great cities where people lived, factories, raw materials, foodstuffs, supplies, and modes of transportation.Footnote 2 All were essential to wage modern war, Mitchell had written in the aftermath of World War I, and all were vulnerable to air attack. Moreover, he deemed that many such targets were fragile, and wrecking them promised a victory both quicker and cheaper than one achieved by surface forces. Air power could attack vital centers directly, avoiding the senseless slaughter that had characterized World War I land combat. Bombers would wreck an enemy’s will to fight by destroying its capability to do so, and the essence of that capability was not its army or navy, but its industrial and agricultural underpinnings. Eliminating industrial production “would deprive armies, air forces and navies … of their means of maintenance.” Air power also offered the chance to attack the will to fight directly, but Mitchell thought that bombers did not necessarily have to kill civilians to wreck a nation’s will to resist.Footnote 3

Mitchell’s conviction that air forces could achieve an independent victory in war by such “beneficial bombing” became a hallmark of Air Corps officers who promoted his vision of independent air power founded on the bomber. Basing many of their assertions on their study of American industry and population centers, they refined Mitchell’s notions into an “industrial web theory” that offered a blueprint for how to wreck an enemy state with air power. After World War II, many American airmen viewed the bombing of Germany and Japan as a vindication of such theories. Although bombing had not singlehandedly defeated Germany, the air campaign against the German homeland had significantly damaged its ability to wage war.

The result was an independent air force with a doctrine geared to achieving an independent victory. Enough similarities remained between the notion of an industrial web and the damage rendered to Germany and Japan for American airmen to make the theory their doctrinal cornerstone. Published a few months after the Eisenhower administration announced its massive retaliation policy, Air Force Manual 1-8 defined strategic air operations as attacks “designed to disrupt an enemy nation to the extent that its will and capability to resist are broken.” Such operations would be autonomous, “conducted directly against the nation itself,” rather than auxiliary operations supporting friendly land and sea forces against an enemy’s deployed armies and navies. The authors concluded that destroying petroleum or transportation systems would cause the most damage to a nation’s will to resist. Only “weighty and sustained attacks,” however, would succeed in wrecking either system.Footnote 4

On the eve of sustained combat in Vietnam, this mindset portended ill for the US Air Force. Although their doctrine stated that the industrial web theory applied to “modern” nations, many airmen equated “modern” to “all,” and in Vietnam they would futilely try to determine the key industrial component that made agrarian North Vietnam tick. Part of the problem was that the airmen’s predecessors had designed the industrial web theory based upon their own vision of the United States, and that vision may not have been accurate. Part of the problem was also that post–World War II airmen had transformed the notion into a guideline for nuclear attack, and the prospects of nuclear bombing did not translate exactly into actual warfare, especially for an agrarian nation like North Vietnam. Yet air force doctrine taught that they did translate, and that preparation for nuclear war sufficed to ready the air force for combat at any level. That belief received a significant boost in October 1962, when the threat of SAC B-52s, supplemented by a fledgling intercontinental ballistic missile force, compelled the Soviet Union to back down during the Cuban Missile Crisis. If the threat of bombing could make the Soviets – the United States’ mightiest potential enemy – retreat, surely that threat would make other, lesser, nations fall into line as well. So believed many American airmen and political leaders as the United States looked for a quick, cheap solution in Vietnam.

Launching Rolling Thunder

With the Saigon regime teetering on the verge of collapse in early 1965 to National Liberation Front (NLF) insurgents and their North Vietnamese allies, air power appeared to offer the answer to South Vietnam’s survival when American political and military chiefs agreed to initiate Rolling Thunder. As to how bombing North Vietnam would yield an independent, noncommunist South Vietnam, there existed a wide disparity of opinion, ranging from the signal air power would send to the North Vietnamese – that bombs would ultimately destroy their heartland and its nascent industrial apparatus – to the signal that it would send to the United States’ South Vietnamese allies – that it would bolster their fighting spirit, making them fight harder and cause them to prevail against the forces of the NLF and the contingent of North Vietnamese troops supporting them. Although many airmen believed that North Vietnam lacked the Soviet Union’s will to resist, and that the threat of aerial destruction would force Hồ Chí Minh to surrender, their motivations for bombing the North also subscribed to their doctrine: they believed that the NLF, which formed the vast bulk of the enemy forces in South Vietnam, could not fight without the support and direction of the North Vietnamese, and that bombing North Vietnam would deny the NLF the capability to keep fighting. Lyndon Johnson and his political advisors endorsed this perspective as well in spring 1965. The notion was the fundamental premise of Rolling Thunder, and one that American airmen would continue to support after Johnson’s political advisors had given up on it. Unfortunately for American leaders, the premise was fundamentally flawed.

Although American political and military leaders frequently stated that the enemy waged guerrilla warfare, they also assumed that the destruction of resources necessary for conventional warfare would weaken the enemy’s capability and will to fight unconventionally. During the Rolling Thunder era, however, the enemy rarely fought at all. Hanoi had only 55,000 North Vietnamese troops in the South by August 1967; the remaining 245,000 communist soldiers were part of the NLF.Footnote 5 None of these forces engaged in frequent combat, and the NLF intermingled with the Southern populace. Enemy battalions fought an average of one day in thirty and had a total daily supply requirement of 380 tons. Of this amount, they needed only 34 tons a day from sources outside the South, a total that consisted of mostly ammunition; the NLF and the People’s Army of North Vietnam (PAVN) troops obtained food from rice fields in the South.Footnote 6 Seven two-and-a-half ton trucks could transport the 34-ton requirement, which was less than 1 percent of the daily tonnage imported into North Vietnam. No amount of bombing could stop that paltry supply total from arriving in the South. Sea, road, and rail imports averaged 5,700 tons a day, yet Hanoi possessed the capacity to import 17,200 tons. Defense Department analysts estimated in February 1967 that an unrestrained air offensive against resupply facilities, accompanied by the mining of Northern harbors, would reduce the import capacity to 7,200 tons.Footnote 7 The amount of goods that the communists shipped south “is primarily a function of their own choosing,” the Joint Chiefs remarked in August 1965.Footnote 8 Their appraisal remained valid throughout Rolling Thunder. Still, by fighting an infrequent guerrilla war, the NLF and PAVN could cause significant losses. In 1967 and 1968, two years that together claimed 25,000 American lives, more than 6,000 Americans died from mines and booby traps.Footnote 9

Initially, though, American political and military chiefs agreed that the NLF could not function without Hanoi’s support. Air force chief of staff Curtis LeMay, and General John P. McConnell, who served as LeMay’s vice chief and succeeded him as chief of staff on February 1, 1965, called for a concentrated air attack ranging from sixteen to twenty-eight days against transportation centers, bridges, electrical power facilities, and the sparse components of North Vietnamese industry. Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp, the commander of Pacific Command, who controlled the forces that would conduct such an attack, eagerly endorsed it, as did Lieutenant General Joseph H. Moore, the commander of the 2nd Air Division in Saigon, who directed many of the air force aircraft that would participate. To air commanders, the “sudden, sharp knock” of a three-week air offensive would not just disrupt North Vietnam’s war effort; it would also disrupt the fabric of Northern economic and social welfare – or, at the minimum, threaten its functioning, much as American bombers had threatened the Soviets in October 1962. American leaders understood that the North Vietnamese received the bulk of their war-making hardware from the Soviets and Chinese, and that Hồ Chí Minh could boast of only a single steel mill, one cement factory, and fewer than ten electric power plants. Yet those leaders also surmised that the threat of bombing could hold the meager Northern industrial apparatus “hostage” to the danger of attack. They believed that Rolling Thunder would creep steadily northward until it threatened the nascent industrial complexes in Hanoi and Hải Phòng, and that Hồ Chí Minh, being a rational man who certainly prized that meager industry, would realize the peril to it and stop supporting the NLF. Denied assistance, the insurgency would wither away, and the war would end with the United States’ high-tech aerial weaponry providing a victory that was quick, cheap, and efficient.

In February 1965, Johnson and his political advisors accepted that air power was an appropriate instrument with which to bully North Vietnam: it would cost fewer American lives than sending in American ground troops; they could focus it on key North Vietnamese targets; and, above all, they could control its intensity. Control was essential for Johnson. Although he had committed personal as well as national prestige to preserving a noncommunist South Vietnam, equally important was ensuring that the war in Southeast Asia did not expand into a larger conflict involving either the Chinese or the Soviets. Remembering Chinese intervention in the Korean War, Johnson was terrified that the Chinese would send troops to support their communist neighbors in North Vietnam or, worse yet, that the Soviets would actively join in the conflict – possibly even with nuclear weapons.Footnote 10 Both the president’s key advisors, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, warned Johnson not to implement the proposed intensive, three-week air campaign against North Vietnam because of the unknown impact that such bombing would have on the communist superpowers. Rusk, as assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs during the Korean War, had seen at first hand the effects of miscalculating Chinese intentions, while McNamara had played a key role in helping resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis. Johnson placed an enormous amount of trust in the opinions of both men.

Besides his fears that Vietnam might expand into World War III, Johnson’s commitment to establishing a “Great Society” caused him to shun a heavy air attack on North Vietnam. He feared that a massive increase in military force in Southeast Asia would advertise the seriousness of the threat to South Vietnam, causing the attention of Congress and the American public to shift away from the social programs that he cherished. A rapid increase in military pressure would have further repercussions. The president hoped to secure a favorable perception of the United States among Third World nations. Too much force in Vietnam might cause those countries to view the American effort as motivated by imperial ambitions or feelings of racial superiority. Exerting too much force against North Vietnam would make the United States appear as a Goliath pounding a hapless David, and likely drive small nations searching for a Cold War benefactor into the communist embrace. Johnson also wished to maintain the support of NATO and other Western allies. The greater the effort in Vietnam, the more allies elsewhere would question the ability of the United States to sustain its military commitments.

Johnson’s conflicting goals combined to produce the main principle of air strategy against North Vietnam: gradual response. American political leaders believed that military force was necessary to guarantee the South’s existence, yet other goals prevented them from unleashing the United States’ full military power. To ensure that the war remained limited, Johnson prohibited military actions that threatened, or that the Chinese or Soviets might perceive as threatening, the survival of North Vietnam. Bombing would begin slowly in the southern part of North Vietnam and incrementally “roll” northward toward the heartland containing Hanoi and Hải Phòng. Meanwhile, Johnson and his political chiefs would scrutinize bombing’s effects, with a wary eye focused on the reactions of Moscow and Beijing. Based on those reactions, as well as the response of the American public and the world community at large, they could tighten or loosen the bombing faucet as they saw fit. Rolling Thunder’s initial attack on March 2, 1965, struck only one target, an ammunition depot well south of the heartland, and was the only attack of the week. The following week fighters bombed barracks and ammunition depots, again south of the 20th parallel, on a single day.

Johnson and his political advisors hoped that the attacks would signal to Hồ Chí Minh that ultimately air power would demolish its meager industrial apparatus north of the 20th parallel. Fighters bombed more targets, on more days, during the third week of March, and the bombs crept northward toward Hanoi. During this span, Admiral Sharp stated that he expected that the limited interdiction would yield success by degrading transportation, diverting manpower to rebuilding roads and bridges, and conveying American “strength of purpose” that would “make support of the VC [Viet Cong] as onerous as possible.”Footnote 11 This faith, also shared by political leaders, that the threat of greater destruction would suffice to make the North Vietnamese balk, stemmed from the Soviet retreat during the Cuban Missile Crisis.Footnote 12 Noted National Security Council official Chester L. Cooper: “It seemed inconceivable that the lightly armed and poorly equipped Communist forces could maintain their momentum against, first, increasing amounts of American assistance to the Vietnamese Army, and subsequently, American bombing.”Footnote 13

Evaluating Rolling Thunder

The belief that Hồ would cower to air power lasted very briefly, although a slim regard for North Vietnam’s tenacity endured throughout the Johnson presidency. By early April 1965, after only six Rolling Thunder missions, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy began pressing Johnson to change the focus of American military effort to ground power. Sharp and other air chiefs redoubled their efforts to convince political leaders to bomb key elements of Northern war-making capability directly, but Bundy, Rusk, McNamara, and general-turned-ambassador to South Vietnam Maxwell Taylor persuaded Johnson to emphasize – and enlarge – the American military effort on the ground in the South. To American political leaders after July 1965, bombing the North would serve as a means of supporting American troops in South Vietnam by denying enemy forces unlimited supplies and placing a “ceiling” on the magnitude of the war that they could fight. Many air commanders, however, continued to advocate increased attacks on North Vietnamese heartland targets in the hopes that air power might ultimately wreck the North’s capability and will to fight.

Johnson’s political restrictions made conducting the systematic air campaign called for by the air chiefs virtually impossible. He initially prohibited B-52s from bombing North Vietnam because he thought that the Chinese or Soviets might deem use of the heavy bomber designed for nuclear missions too provocative,Footnote 14 although he ordered the bombers to attack targets in South Vietnam starting in June 1965. B-52s did not bomb the North until 1966, when Johnson permitted them to attack targets just north of the 17th parallel. Targets in Hanoi remained “off-limits” to all aircraft until the summer of 1966. Johnson then forbade air commanders from bombing within a thirty-mile (48-km) radius from the center of Hanoi, a ten-mile (16-km) radius from the center of Hải Phòng, and thirty miles (48 km) of the Chinese border without his personal approval. Besides determining where his pilots could attack, Johnson also decided how often they could do so. He paused Rolling Thunder completely on eight occasions between March 1965 and March 1968, with reasons that varied from giving the North Vietnamese time to negotiate to observing Buddha’s birthday. Meeting with key advisors Rusk, McNamara, and Bundy over lunch in the White House on Tuesday afternoons, Johnson selected specific North Vietnamese targets for attack in weekly or biweekly increments. Not until October 1967 did these luncheons regularly include army general and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Earle Wheeler; prior to that time, no military representative usually attended.Footnote 15

The lack of a military presence during the Tuesday lunches blatantly revealed Johnson’s distrust of his generals and caused those wearing the uniform enormous frustration at all levels. Because the luncheon attendees did not publish the results of their sessions, perceptions of the president’s decision-making frequently differed. Conflicting guidance reached air commanders and produced confusion. Pilots learned that they had authority to attack moving targets such as convoys and troops, but could not attack highways, railroads, or bridges with no moving traffic on them.Footnote 16 Moreover, the precise definition of “moving targets” was unclear to those flying Rolling Thunder missions.

Like many wing commanders, air leaders orchestrated the offensive against North Vietnam as best they could given presidential constraints. They refused to surrender the deeply ingrained notion that bombing could break an enemy’s capability and will to resist, and their targeting proposals that McNamara carried to the Tuesday lunches adhered to the basics of air force doctrine. Johnson, increasingly desperate for a solution to the war, ultimately bowed to many of their targeting suggestions, although he never gave his air chiefs carte blanche to attack North Vietnamese target systems in a coordinated series of “sharp, hard knocks.” Raids occurred incrementally over long spans of time, with the effort against Northern transportation counting for 90 percent of all Rolling Thunder missions and running from March 1965 to June 1966 (and during intervals between shifts in bombing emphasis); an attack on oil storage areas occurring from late June to early September 1966; and raids against Northern industry and electric power plants transpiring in March, April, and May 1967. After those attacks, the objective wavered. At the end of March 1968, in the midst of the domestic furor over the communist Tet Offensive, Johnson restricted bombing to targets below the 19th parallel in an effort to spur peace negotiations. On November 1, 1968, he halted all attacks on North Vietnam and brought Rolling Thunder to a close.

In the end, the aerial assault could break neither Hanoi’s capability nor its will to keep fighting, nor could Rolling Thunder place a “ceiling” on the magnitude of the war that the North Vietnamese and NLF could fight. The 1968 Tet Offensive demonstrated in graphic fashion bombing’s failure to limit enemy operations. Rolling Thunder never suited the character of the war, and the inability – or unwillingness – of many air chiefs to recognize that fact produced “military constraints” that further limited bombing effectiveness. Unable to produce telling results against an enemy that rarely fought, air commanders adopted a method of combat scorekeeping resembling the body count approach used by ground commanders in the South: sortie count. Admiral Sharp’s April 1966 division of North Vietnamese airspace into seven permanent bombing zones, or “Route Packages,” triggered a competition between navy and air force commanders to produce the most sorties in their respective Route Packages on a given day.Footnote 17 The totals flown then became a warped measuring stick of bombing effectiveness. To increase the count, some commanders called for attacks with less than full bomb loads, which in turn endangered additional flyers;Footnote 18 one navy A-4 pilot admitted that he attacked the Thanh Hóa Bridge, one of the North’s most heavily defended targets, with no bombs at all but was told simply to strafe the structure with 20mm cannon fire.Footnote 19

Besides military limitations, “operational” controls further restricted Rolling Thunder. These constraints consisted of such vagaries as geography, weather, aircraft types, and enemy defenses. North Vietnam’s lush terrain was ideal for camouflage, and the enemy frequently resorted to deception. Hanoi also exploited the proximity of Laos and Cambodia by snaking the sophisticated series of pathways that combined to form the Hồ Chí Minh Trail through eastern areas of both countries. Most of the 3 million tons of bombs dropped in Laos fell in the vicinity of the trail, which included more than 1,800 miles (2,900 km) of truckable roadways winding through terrain as high as 8,000 feet (245 m) as well as triple-canopy jungle and dense rain forests. Although the NLF and North Vietnamese did not need the bulk of equipment transported on it during the Johnson era of the war, they stockpiled the goods for major assaults like the Tet Offensive and the siege of Khe Sanh. Weather was one of the air campaign’s most significant operational controls. From September to April, the dense clouds of the winter monsoons made continuous bombing impossible. The monsoons prevented Rolling Thunder from starting in late February 1965 and canceled numerous missions in March, when Johnson’s political advisors had the greatest faith in its success. Most of the raids scheduled during the monsoon season against fixed targets such as bridges became interdiction strikes because clouds obscured the primary objective. In 1966, only 1 percent of the year’s 81,000 sorties flew against fixed targets proposed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff,Footnote 20 and weather was a key reason for the low total.

Of the aircraft types that performed most Rolling Thunder bombing, none was well suited for North Vietnam’s forbidding environment. The air force relied primarily on the Republic F-105 Thunderchief, a slow-turning, single-seat fighter designed during the 1950s as a nuclear attack aircraft, and the McDonnell-Douglas F-4 Phantom, developed by the navy as a high-altitude interceptor and modified for ground attack. It suffered from a vulnerability to ground fire, poor rear cockpit visibility, and engines that emitted thick, black smoke, revealing its location. The navy used the Phantom for bombing as well, but relied mostly on the McDonnell-Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, a diminutive single-seat fighter that could carry only four tons of bombs. Together, these aircraft flew against a defensive array that sported 200 surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites, 7,000 anti-aircraft guns, a sophisticated ground-controlled intercept (GCI) system, and 80 MiG fighters by August 1967. Hanoi gained the reputation as the world’s most heavily defended city, and veteran F-105 pilot Jack Broughton labeled North Vietnam as “the center of hell with Hanoi as its hub.”Footnote 21 In 1967, the last full year of Rolling Thunder, 326 American aircraft were lost over the North; 921 were lost during the entire campaign of three and a half years.Footnote 22

Figure 2.1 An F-105 “Thunderchief” with a full load of sixteen 750 lb bombs; it was the US Air Force’s primary aircraft for bombing North Vietnam during Operation Rolling Thunder.

The air offensive originally envisioned as a quick, cheap alternative to ground war proved to be neither. Moreover, Rolling Thunder spurred both China and the Soviet Union to provide North Vietnam with not only military hardware but also economic backing. As a result of the support received from the communist superpowers, the North’s gross national product actually rose during each year of Rolling Thunder. Hồ Chí Minh knew that the Chinese and the Soviets were vying for influence in his nation, and he adroitly played one against the other to gain maximum support. The bombing also provided Hồ Chí Minh with a means to rally the Northern populace behind the war effort. He realized that the constrained bombing would cause little damage, but the American air presence persisted over North Vietnam. Thus, he could consistently point to the air attacks as examples of American barbarism, a claim made time and again by his effective propaganda ministry. “In terms of its morale effects,” RAND analyst Oleg Hoeffding argued in 1966, “the US campaign may have presented the [North Vietnamese] regime with a near-ideal mix of intended restraint and accidental gore.”Footnote 23 Rolling Thunder killed an estimated 52,000 civilians out of a population of 18 million;Footnote 24 in contrast, the first B-29 incendiary raid against Tokyo in World War II had killed at least 84,000 Japanese civilians on a single night.Footnote 25

Rolling Thunder destroyed 65 percent of North Vietnam’s oil storage capacity, 59 percent of its power plants, 55 percent of its major bridges, 9,821 vehicles, and 1,966 railroad cars,Footnote 26 but such destruction counted for little in terms of ending the war. The myriad of political, military, and operational controls that plagued the air campaign helped prevent it from achieving Johnson’s goal of a noncommunist South Vietnam. Without those constraints, however, its prospects were dim as long as the enemy chose to wage an infrequent guerrilla war. Air force doctrine had discounted the probability of limited war, especially one in which the enemy rarely fought. That doctrine had also claimed that victory through air power was likely regardless of the character of the war, and that the keys to victory were identifying and then wrecking the ingredients tying together the enemy’s capability and will to resist.

Given the type of war the communist army fought, the only two targets that might have hurt its war effort and the support it received were people and food. None of Johnson’s advisors, military or civilian, advocated such attacks. Yet even had raids against population centers or the Red River dikes occurred against North Vietnam – and succeeded in knocking the North out of the war – in all likelihood they would have had minimal impact on achieving Johnson’s war aim. The main enemy was the NLF in the South, not the North Vietnamese, and the NLF were not dependent on Hanoi’s support. Nor were they dependent on Hanoi’s direction. Many NLF soldiers and their leaders fought against the American-backed Saigon regime because it was corrupt and mistreated the Southern populace, rather than because of a commitment to North Vietnamese communist ideology.Footnote 27 Indeed, after an American-endorsed coup had ousted the failing government of Ngô Đình Diệm in late 1963, South Vietnam endured seven different regime changes – including five coups – in 1964 alone, and none of the governments had popular support. The regimes that followed remained equally corrupt and out of touch with the bulk of the Southern population.Footnote 28 The United States’ political leaders supported those governments because they were noncommunist, but no amount of American air power could sustain them. Moreover, as long as the NLF kept the war’s tempo limited, Rolling Thunder could not have a decisive effect on the ground war in the South.

Campaigns in the South

Johnson’s July 1965 decision to expand American ground forces from 82,000 to more than 200,000 by the end of the year determined that the war would be won or lost in South Vietnam, where auxiliary air power supported the ground struggle waged by American and South Vietnamese troops. While the US Air Force and the US Navy fought two separate and often unrelated air wars against North Vietnam, in the South no fewer than six isolated air wars, with disparate arrays of air power, transpired simultaneously. Air force fighters such as F-4s, F-105s, and F-100s, based in South Vietnam and Thailand and directed by 7th Air Force Headquarters in Saigon,Footnote 29 formed a large part of that combined effort. Yet fighters were not the only US Air Force contribution to the Southern ground battle. Beginning in June 1965, Strategic Air Command’s B-52s began bombing suspected enemy positions in South Vietnam in what became a massive operation known as Arc Light. That effort entailed bombers flying 12- to 14-hour round-trip missions from Andersen Air Base, Guam, as well as missions starting in 1967 from U-Tapao Air Base, Thailand, and, for a brief period beginning in January 1968, Kadena Air Base, Okinawa. All told, the giant bombers flew 126,615 Arc Light sorties and were responsible for dropping most of the 4 million tons of bombs dropped on the South, the majority of which fell in 30-ton increments per bomber.Footnote 30 Navy fighters, consisting largely of F-4s, A-4s, and A-6s, bombed targets in South Vietnam as well, flying from carriers positioned at “Dixie” station in the South China Sea in contrast to the more familiar “Yankee” station in the Tonkin Gulf used for attacking North Vietnam.

Naval air often supported US Marine operations in the I Corps section of northern South Vietnam, but the marines also had their own air component. Flying F-4s, A-4s, A-6s, A-1 Skyraiders, and numerous helicopters, the marines supported their ground units from bases throughout the I Corps area, especially Đà Nẵng. By far the largest “air force” in the Vietnam War belonged to the US Army, which sent almost 12,000 helicopters to the conflict. Army “choppers,” ranging from the workhorse Chinook to the ubiquitous Bell UH-1, or “Huey,” dotted the South Vietnamese skies, though flying in that force was not the safest of pursuits – enemy forces shot down 4,842 helicopters.Footnote 31 Although the army relied on its helicopter force for delivering men, materiel, and firepower throughout the South, the air force provided the major airlift support in South Vietnam with its fleet of turbo-prop transport aircraft – the C-123 Provider, C-130 Hercules, and C-7A Caribou, from Pacific Air Forces (PACAF)Footnote 32 – and two jet transports – the C-141 Starlifter and giant C-5 Galaxy that were part of Military Airlift Command. Last and, in many respects, least in terms of air forces operating in the South was the South Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF). Created in the image of the US Air Force, the VNAF contained A-1, A-37, and, later in the war, F-5 attack aircraft, as well as a smattering of transports and helicopters. It provided close air support to and transport for the South Vietnamese army, but suffered from leadership problems, especially after the flamboyant Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ left the VNAF to become prime minister in the summer of 1965.

Whereas the lack of unity of command plagued the bombing of North Vietnam, that same deficiency hampered the various air wars occurring simultaneously over the South. The lack of a single air manager made coordination difficult, even among aircraft flying from the same service. Strategic Air Command never yielded complete control of its B-52s to commanders in Vietnam because the aircraft’s primary mission remained preparation for possible nuclear war; engineers had refurbished the behemoths to carry conventional ordnance instead of nuclear weapons, but the bombers still retained their nuclear capability. Thus, air crews rotated to Southeast Asia in 179-day increments on temporary duty, and then returned to stateside assignments for extended periods to serve on nuclear alert. Initially, Johnson directed B-52 raids in the South through SAC, but in August 1965 he transferred that decision-making power to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. After complaints from 7th Air Force about the long-distance control, in April 1966 the Joint Chiefs transferred B-52 targeting approval for raids in South Vietnam to Admiral Sharp in Honolulu, and in November 1966 Sharp gave US Army general William C. Westmoreland, the commander of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), in Saigon, the authority to approve all Arc Light targets, though Westmoreland still had to coordinate with SAC in directing the aerial assault against southern targets.Footnote 33

Westmoreland refused to yield control of B-52s to air force general William W. Momyer, the 7th Air Force commander, revealing Westmoreland’s view of the B-52 as flying artillery that should be controlled by an army commander. In contrast, Momyer wanted to coordinate the effort of his fighters with the B-52s and guarantee that the bombers would attack only defined targets of men and supplies.Footnote 34 His pleas fell on deaf ears. Westmoreland’s MACV staff, predominantly comprising army officers focused on fighting the ground war, not only made B-52 targeting decisions but also selected the preponderance of Southern targets for 7th Air Force fighters as well by virtue of directing MACV’s intelligence branch. As a result, the air interdiction that occurred in South Vietnam was haphazard and piecemeal.

Figure 2.2 The B-52 “Stratofortress” could carry up to 30 tons of conventional bombs on missions in Southeast Asia.

The air force’s struggle with the army for control of the B-52s typified the attitude of many air leaders with regard to how to conduct the air war in the South. Air force chief of staff McConnell, who pressed vigorously for three weeks of “hard knock” bombing to initiate Rolling Thunder, tried equally hard to obtain an aerial victory in the South. McConnell stated in August 1965 that ground forces alone could not defeat the NLF and that only air power could defeat the enemy. The general meant air power provided by the United States Air Force, however. When the army prepared to launch its first airmobile offensive into the Ia Đrӑng Valley in November 1965 with the 1st Air Cavalry Division’s 434 helicopters, McConnell ordered air force commanders in Hawaii and Saigon to keep detailed statistics on every phase of the operation to show that the army was incapable of conducting such an offensive without support from air force fixed-wing aircraft. Many air force commanders were also hesitant to condone transformation of the old C-47 transport into the AC-47 gunship, because they believed that endorsement of the concept would legitimize the army’s use of armed transport helicopters, which would in turn partly eliminate the army’s need for air force air support. McConnell disapproved of using the B-52s in the South because suitable targets were scarce, and Westmoreland was reluctant to send ground troops into the bombed areas to determine the exact amount of damage inflicted. Yet, in a twisted bit of parochial logic, in September 1965 McConnell endorsed continued B-52 bombing in South Vietnam “since the Air Force had pushed for the use of air power to prevent Westmoreland from trying to fight the war solely with ground troops and helicopters.”Footnote 35

Bombing in the South with B-52s yielded mixed results. The initial Arc Light missions produced little damage, as the bombs missed NLF areas, or the enemy, possibly tipped off by agents who had infiltrated the South Vietnamese military, fled before the bombers arrived.Footnote 36 On the other hand, if intelligence could pinpoint enemy forces, as occurred during the 1965 battle of the Ia Đrӑng and the 1968 siege of the marine outpost at Khe Sanh, then the effects could be devastating. On November 14, 1965, 18 rapidly dispatched B-52s dropped 344 tons of bombs on two North Vietnamese regiments to wreck their counterattack against the 1st Air Cavalry Division at the Ia Đrӑng.Footnote 37 During the 77-day siege of Khe Sanh, from January 15 to March 31, 1968, B-52s flew 2,548 sorties and dropped 59,542 tons of bombs, and, along with air force, navy, and marine fighters and marine artillery, completely destroyed two attacking North Vietnamese divisions.Footnote 38 Trương Như Tảng, the NLF minister of justice who survived several B-52 attacks, described a raid as “an experience of undiluted psychological terror.” He remembered: “The first few times I experienced a B-52 attack it seemed, as I strained to press myself into the bunker floor, that I had been caught in the Apocalypse. One lost control of bodily functions as the mind screamed incomprehensible orders to get out.” Trương Như Tảng later noted that he survived the attacks because of the advance warning provided by Soviet intelligence trawlers that observed B-52 takeoffs from Guam and relayed the information to the North Vietnamese and the NLF; flights from Thailand were similarly monitored.Footnote 39 Such warnings were of limited value, though, if the forces the United States was fighting chose to wage open warfare, as was the case at the Ia Đrӑng and Khe Sanh. Whenever the North Vietnamese or NLF chose to mass and fight a “conventional” war of movement in such remote areas, they paid the price to American air power. Until the 1968 Tet Offensive, they rarely chose to do so.

The enemy’s restrained combat during the Johnson presidency made it difficult for air and ground commanders alike to determine air power’s impact on the ground battle. “Unfortunately, for the planners at the time and for subsequent researchers, reliable quantitative indications of results were unobtainable,” observed air force historian John Schlight. “For one thing, the Air Force had no clear-cut objective of its own to measure results in South Vietnam.”Footnote 40 Most air force commanders preferred to use their weaponry in independent operations, like interdiction, that offered the prospect of large-scale returns, rather than for auxiliary missions, like close air support, that provided a limited amount of assistance to a single ground unit. To gauge bombing success in the South, Admiral Sharp relied on the arcane sortie-count methodology used to evaluate Rolling Thunder. In April 1966 he told assembled commanders in Honolulu that he aimed to complete the planned sortie totals for the year despite a shortage in conventional ordnance that would force aircraft to fly with less-than-full bomb loads.Footnote 41

Westmoreland further clouded the impact of air force attacks by telling air commanders to label all air strikes in the South as close air support missions. His directive displayed his unwavering conviction that the entire country of South Vietnam was simply one large battlefield, and that all air power supported his massive ground campaign on it. Nonetheless, the US Air Force continued to track sorties used to assist troops actually engaged in combat with enemy forces, and found that only 3 percent of all sorties flown in South Vietnam through the end of 1966 went to that end. In addition, the US Army requested close air support for only one out of every ten engagements with the enemy. A key reason for the dearth of requests was that half of all ground battles in the South lasted less than twenty minutes, which was too short a span to call upon air power for assistance.Footnote 42

The limited amount of ground combat requiring close air support, along with the enemy’s propensity to avoid fighting, led to the development of “free fire zones” in South Vietnam. These areas were “known enemy strongholds … virtually uninhabited by noncombatants” where any identified activity was presumed to stem from enemy forces and was thus susceptible to immediate air or artillery strikes.Footnote 43 In many cases, American or South Vietnamese troops had removed South Vietnamese peasants from the area, resulting in the conviction that any troops now appearing in the zone would be NLF. Although the notion seemed to guarantee solid results for air power, in actuality it frequently proved disastrous to the oft-repeated goal of winning the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese peasantry. Religious beliefs compelled many villagers to return to ancestral homes and graves that they had been forced to leave, and aerial reconnaissance sometimes mistakenly identified their return as the arrival of enemy soldiers. Such instances had disastrous consequences, and virtually guaranteed that any survivors who might have been apathetic about the war before the attack would now side with the enemy.

Unlike during Rolling Thunder, President Johnson and his political advisors placed few restrictions on the air wars in the South. Johnson deemed that the Chinese or Soviets would raise little outcry over air raids on South Vietnamese territory, and that raids condoned by Southern leaders would not attract the attention of the world press. Until the 1968 siege of Khe Sanh, air force aircraft based in Thailand could not attack targets in South Vietnam without first landing in the South and then flying from there.Footnote 44 Air commanders also had to receive permission from South Vietnamese province chiefs, who were responsible for the welfare of everyone living in their province, before launching air strikes.Footnote 45 Yet, as was the case with free fire zones, obtaining clearance to attack did not guarantee that innocent civilians would not be injured or killed. A favorite technique of NLF units was to fire one or two shots at an American patrol from a South Vietnamese village and then quickly leave the area. The patrol leader might respond by requesting air support and, if the local province chief approved the request, the destruction of an innocent hamlet could result.

In short, applying air power to the struggle in South Vietnam was an enormously difficult proposition. The war was not just a guerrilla conflict, but a civil war, and the key to victory was controlling passion rather than position. The location of frontlines or the amount of men and equipment lost had meaning only in terms of how those variables affected the remainder of those willing to fight, and the air force attempted to eliminate that desire from the enemy through Rolling Thunder. Concurrently, air commanders faced the challenge of how best to provide the army and marines with auxiliary doses of air power. To many ground commanders, the answer was simply to provide more firepower sooner. The disparate air forces that flew over South Vietnam could usually reply with large amounts of ordnance, although not always as rapidly as ground commanders would have liked. In a war for the control of hearts and minds, however, more bombs was not necessarily the right answer.

Airlift, a nonlethal form of air power, offered not only the potential to support combat units with men and equipment – as the C-130s, C-123s, and C-7s did for the beleaguered marines at Khe Sanh – but also to carry government officials, food, clothing, and building materials to villages throughout South Vietnam. Such “mercy missions” were in fact conducted, but the “pacification” effort in the South never received the emphasis of the combat airlifts. Moreover, airlift was vulnerable to ground fire, and it was transitory. Johnson’s goal of a stable, independent, noncommunist South Vietnam could be achieved only through a long-term presence on the ground. Accomplishing his war aim would have required a massive outlay of manpower, as well as a fundamental change of mindset about how to use those men. After three years of warfare and the shock of the Tet Offensive, neither the president nor the American public was willing to up the ante, and the war aim changed.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, several legacies emerged from air power’s ordeal in Vietnam. The dismal lack of unity of command displayed there spurred development of the Joint Forces Air Component Commander (JFACC) concept, in which a single air commander directs the flying activities of multiple services to achieve objectives sought by the Joint Force Commander (JFC). The American military first applied the JFACC notion on a large scale in combat against Iraq in 1991, and the success of the concept in Operation Desert Storm cemented its use as a command element since that conflict. In terms of air force doctrine, the perceived success of Linebacker II, Richard Nixon’s December 1972 bombing campaign against Northern targets, in compelling the North Vietnamese to negotiate reinforced the belief that air power could achieve political goals cheaply and efficiently. The 1984 edition of the air force’s Basic Doctrine Manual, the first published after the Vietnam War, noted that, “unless offensive action is initiated, military victory is seldom possible … Aerospace forces possess a capability to seize the offensive and can be employed rapidly and directly against enemy targets. Aerospace forces have the power to penetrate to the heart of an enemy’s strength without first defeating defending forces in detail.”Footnote 46 The manual further encouraged air commanders to conduct strategic attacks against “heartland targets” that would “produce benefits beyond the proportion of effort expended and costs involved,” but cautioned that such attacks could “be limited by overriding political concerns, the intensity of enemy defenses, or more pressing needs on the battlefield.”Footnote 47

The impact of such “overriding political concerns” on the application of air power is a key legacy of the air wars in Vietnam. To commanders who had fought as junior officers in World War II, where virtually no political constraints limited the application of military force, the tight controls that Johnson placed on bombing North Vietnam chafed those charged with wielding the air weapon. Navy admiral U. S. Grant Sharp, who directed Rolling Thunder as the commander of Pacific Command, wrote in the preface of his 1977 memoirs (titled Strategy for Defeat): “Our air power did not fail us; it was the decision makers. And if I am unsurprisingly critical of those decision makers, I offer no apology. My conscience and my professional record both stand clear. Just as I believe unequivocally that the civilian authority is supreme under our Constitution, so I hold it reasonable that, once committed, the political leadership should seek and, in the main, heed the advice of military professionals in the conduct of military operations.”Footnote 48 Many American airmen from the war likely agreed with Sharp’s critique.

Rolling Thunder highlighted how political constraints could limit an air campaign. Indeed, in the American air offensives waged since Vietnam – to include the use of drones against “high-value” terrorist targets – such constraints have continued to restrict the use of military force. Projecting a sound image while applying air power was difficult enough for American leaders in Vietnam; today’s leaders must contend with 24/7 news coverage as well as social media accounts that enable virtually anyone to “spin” a story and reach a large audience. In the limited wars that the nation will fight, such constraints will always be present and will produce rules of engagement that limit air power. “War is always going to have restrictions – it’s never going to be LeMay saying ‘Just bomb them,’” stated retired air force general Richard Myers, Vietnam veteran and former air force chairman of the Joint Chiefs.Footnote 49 Against insurgent enemies, political controls may well undermine the political objectives sought. When that occurs, kinetic air power’s ability to yield success will be uncertain at best.

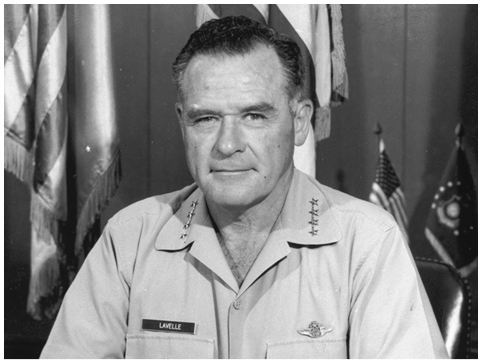

Yet because air power, as a subset of war, is not only a political instrument, but also one that is applied by humans, it will be subject to whims and frailties of the political leader who chooses to rely on it. Lyndon Johnson was a master politician when it came to accomplishing his domestic agenda; foreign affairs plagued him incessantly while in office, with Vietnam finally undercutting his cherished Great Society. In contrast, Richard Nixon saw himself as a Patton-like figure who could swiftly and efficiently brandish military force to achieve his aims. He felt little compunction in berating his air commanders, or – in the case of 7th Air Force commander General John Lavelle in 1972 – casting one adrift when he thought that doing so might save him embarrassment. Nixon believed that air power gave him the ideal military tool for threatening an opponent or persuading an ally, and that perspective has gained traction in the White House since he left it. The past five occupants of the Oval Office have all relied heavily on air power in the conflicts they fought. The political goals pursued – “stability,” “security,” and, on occasion, “democracy” – have proven difficult to achieve with any military force, particularly with air power. Its siren song is an enticing one, however, as Johns Hopkins professor Eliot Cohen has astutely observed: “Air power is an unusually seductive form of military strength, in part because, like modern courtship, it appears to offer gratification without commitment.”Footnote 50 That promise is a dangerous one, as General Myers warns: “The last thing that we want is for the political leadership to think war is too easy, especially in terms of casualties. It’s awful; it’s horrible, but sometimes it’s necessary. [The decision for war] needs to be taken with thoughtful solemnness – with the realization that innocent people, along with combatants, will get hurt.”Footnote 51 Were he alive today, the Prussian military philosopher Carl von Clausewitz would doubtless nod at General Myers’s observation.

Clausewitz, of course, never saw an airplane, though if he had his air power notions would likely have been unsurprising. Had he examined the United States’ air wars in Vietnam, he would certainly have commented about the difficulty of achieving political objectives in a limited war. In all probability, he would have looked at Johnson’s Tuesday lunch targeting process, the Route Package system dividing North Vietnamese airspace, the creation of free fire zones in the South, Nixon’s condemnation of his air commanders and dismissal of General Lavelle, the repetitive B-52 routing for Linebacker II, and any number of other elements, and stated simply, “Friction rules.” “Everything in strategy is very simple,” Clausewitz wrote, “but that does not mean that everything is very easy.”Footnote 52 Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the air wars in Vietnam is the one that applies to any military strategy – uncertainty, chance, danger, and stress will be certain to limit it.

Figure 2.3 General John D. Lavelle was accused of authorizing illegal bombing raids against North Vietnamese targets and was forced into retirement in 1972.