A long-standing finding in public opinion research is that party cues—information about what positions political parties take on policy issues—influence citizens’ policy opinions: citizens become more supportive of a policy when they learn that their party endorses it (Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014). Yet, scholars continue to vigorously debate the nature of party cue effects on public opinion. A pertinent concern is that “[i]nstead of permitting us to act like better-informed versions of ourselves, [party cues] may lead us to mindless support of, or opposition to, policies and candidates” (Bullock Reference Bullock, Suhay, Grofman and Trechsel2020, 129). If citizens just follow the position of their party—even if the policy goes against their interests or values—it “raises fundamental concerns about who governs in contemporary democracies” (Freeder, Lenz, and Turney Reference Freeder, Lenz and Turney2019, 288) because “elected party elites may instill the very opinions to which they respond” (Druckman Reference Druckman2014, 477).

But do citizens follow their party when they have a clear personal stake in policy? The answer to this question is critical to understanding how powerful—or limited—party elites are in shaping citizens’ policy opinions. We advance this debate by studying the influence of party cues in a context where citizens’ self-interest—defined as the direct and obvious effects of a policy on the material well-being of the citizen’s own personal life (Chong Reference Chong, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013, 104; Sears and Funk Reference Sears and Funk1991, 16)—was clearly at stake.

An important literature seeks to empirically assess the limits to party elite influence when a party’s position goes against citizens’ ideological values (Barber and Pope Reference Barber and Pope2019; Chong and Mullinix Reference Chong and Mullinix2019) or when citizens have detailed policy information available (Boudreau and MacKenzie Reference Boudreau and MacKenzie2014; Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017; Bullock Reference Bullock2011; De Angelis, Colombo, and Morisi Reference De Angelis, Colombo and Morisi2020; Peterson Reference Peterson2019). While this work has greatly advanced our knowledge on partisan elite influence, it has paid only scant attention to the role of self-interest. Thus, to date, we know very little about the influence of party cues in situations where citizens have a strong personal stake in policy—a stake that gives them a reason to go against the party line. Drawing on current theorizing about when self-interest is particularly likely to matter, we study a rare instance where “people actually have a stake in a policy and can see that they have a stake” (Chong Reference Chong, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013, 105). Do party cues influence citizens’ policy opinion even when their party advocates a policy that goes against citizens’ self-interest? If so, how?

We present an experimental test of party cue effects in an unusual context. Our research design exploits a naturally occurring, sharp variation in party cues during a contentious collective bargaining conflict in Denmark where the self-interest of public employees was clearly at stake and where major political parties went against it. The rare combination of context and experimental design offers an opportunity for investigating whether self-interest limits the influence of party cues on citizens’ policy opinions.

We make two contributions. First, we study a most likely case for self-interest to matter, and yet, we find that party cues move opinion by at least the same magnitude found in previous work. This emphasizes the power of parties to shape public opinion, even on issues with major personal consequences for citizens. Secondly, however, we show that party cues do not lead citizens to go against their self-interest. Rather, using a novel approach to study how party cues influence the distribution of opinion, we find that parties mostly temper the pursuit of self-interest by moderating the most extreme policy demands. This finding not only demonstrates the value of analyzing the distribution of opinion to interpret the average treatment effect in an experiment, it also highlights an unappreciated role for parties in moderating—not fueling—extreme opinion.

Empirical Setting

We conducted our study in Denmark in the spring of 2018. Here, the labor unions representing public employees went into a highly dramatic confrontation with public employers during the collective bargaining. Forming a historic alliance, the unions raised several demands (e.g., higher salaries) and announced a large-scale strike to put pressure on public employers (Hansen and Mailand Reference Hansen and Mailand2019). Denmark has one of the largest public sectors in the world, employing almost a third of the labor force (OECD 2019, 87), and a very high union density of more than 80% among public employees (Andersen, Dølvik, and Ibsen Reference Andersen, Dølvik and Ibsen2014, 74). Thus, naturally, the bargaining conflict took center stage in national politics and news coverage.

Rather unwillingly, leading politicians from the major political parties were drawn into the center of the conflict because they, by virtue of being chief executives in local and national government, were forced to take the employer’s side. This was particularly evident when the largest public employer, Local Government Denmark—an organization led by a board of mayors and other leading local politicians, representing all 98 municipalities in Denmark—refused the unions’ demands and announced a lockout of 250,000 public employees, escalating the conflict to an unprecedented level.

This conflict offers a dual advantage for studying whether self-interest limits the influence of party cues on citizens’ policy opinions: the issue had obvious implications for citizens’ self-interest and we can credibly vary party cues. First, the conflict represents an issue where the self-interest for one group of citizens—public employees—was obviously at stake (i.e., they benefit from higher salaries). Moreover, given high exposure to the conflict through the news media and strong union mobilization, most publicly employed citizens were made aware of the stakes. This way, we avoid a common pitfall in previous work on self-interest that “people are frequently unaware of the implications of the policies for themselves and their families” (Chong Reference Chong, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013, 102). In addition, our survey allows us to validate that public employees were aware of the implications of the policy. This way, we avoid another common limitation that “there is usually no independent confirmation that the respondents share similar beliefs about the impact of the policy” (Chong Reference Chong, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013, 102). Hence, this policy issue should be a most likely case for self-interest to matter and for public employees not to follow their party. Public employees, therefore, are the population of interest in this study.

Second, our case provides sharp variation in party cues. Coincidentally, the chairmanship of the public employers in Local Government Denmark was scheduled to change in the midst of the conflict. Just one day after the chairman of Local Government Denmark—a mayor from the major center-right party, the Liberals (Venstre)—announced a lockout of 250,000 public employees, the chairmanship switched to a mayor from the major center-left party, the Social Democrats. This naturally occurring variation in partisanship of the chairman made it possible to realistically vary party cues in our experiment.

Using this case, we can test whether public employees, who have an obvious interest in opposing the position taken by public employers, follow their party’s position and go against their self-interest when they learn that their party sides with the public employers.

Research Design

To test the effects of party cues among public employees in this context, we designed an experiment and embedded it in a national online survey in Denmark. Our survey had three notable features (see details and ethical considerations in Appendix A). The first was its timing. We fielded the survey from March 16 through April 19, 2018, at the height of the bargaining conflict but before a collective agreement was reached on April 27. This ensures that we studied opinions when public employees’ attention and mobilization peaked. Second, given our population of interest, we sampled citizens aged between 25 and 65 years working in the public sector (we also surveyed privately employed citizens, see Appendix A). Third, because we are interested in whether public employees would follow their party when it advocated a policy that went against their self-interest, we sampled citizens supporting either the Social Democrats or the Liberals (or any allied party). We measured partisanship by asking which party they would vote for “if a national election was held tomorrow.” In Appendix F, we show that our results replicate with alternative measures of partisanship. Partisanship was measured before the party cue experiment to avoid concerns about endogeneity with experimental treatments. Our sample of public employees was almost evenly balanced on partisanship, with 1,628 completed interviews in total.

Validating Whether the Self-Interest of Public Employees Was at Stake

We used two types of survey questions to validate that public employees indeed did see that their self-interest was at stake in the collective bargaining conflict (full results appear in Appendix C). First, we used three survey questions to show that, as expected, public employees felt much personally affected by the outcome of the conflict. Around half of the public employees (48%) expected to be personally involved in a strike or lockout; even more thought the outcome of the collective bargaining would directly affect them financially (58%, to a very large/large/some degree). Unsurprisingly given these stakes, three out of four (76%) public employees followed the collective bargaining (very) closely. Second, we measured policy opinions on four key aspects of the conflict: the employers’ lockout of employees, how much public employees’ salaries should increase, whether public employees should have a stated right to paid lunch break, and whether teachers should be allowed to renegotiate their work hours (question wordings in Appendix B). As expected, public employees expressed very high support for the unions’ demands, further validating they did see that their self-interest was at stake.

Party Cue Experiment

To test how public employees responded when their party sided with public employers and advocated a policy position that went against citizens’ self-interest, we designed a party cue experiment that took advantage of the actual shift in chairmanship of Local Government Denmark. We manipulated party cues by modifying each of the four opinion questions described above to include explicit party positions. For example, party cue versions of the salary question read, “The public employees and employers disagree on the employees’ salary development, among other things. [The Social Democrats/The Liberals] support the employers’ wish to put a cap on public employees’ salary increases. As chairman of Local Government Denmark, [Jacob Bundsgaard from the Social Democrats/Martin Damm from the Liberals] has issued a lockout notice to 250,000 municipal employees to pressure employees to accept lower salary increases. To what extent do you agree or disagree that public employees’ salary increases should be capped?” Responses were measured on a seven-point scale from “completely disagree” to “completely agree” with a don’t know option. We recoded each item to range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating support for the unions’ position (“don’t know” responses were coded 0.5). To increase reliability, we created an index averaging the four items (alpha = 0.76). Respondents were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: no party cue, a Social Democratic cue, or a Liberal cue, always receiving four questions within the same condition.

Party Cue Effects When the Party Goes Against Citizens’ Self-Interest

Public employees were fully aware that their self-interest was at stake in the collective bargaining and were strongly mobilized in support of the unions’ positions in the conflict. In this context, where self-interest is most likely to dominate party cues, our experiment tests to what degree public employees were willing to follow their party when they were told that the party went against their self-interest and sided with the public employers.

What size of party cue effects should we expect? A useful benchmark comes from Clifford, Leeper and Rainey (Reference Clifford, Leeper and Rainey2019, 22) who, in an attempt to provide “the most generalizable estimate of party cue effects to date,” analyzed 48 policy issues in an experimental study. They found that when exposed to party cues (compared with no cues), participants were around 8 percentage points more likely to agree at least somewhat with the position of their party. Treatment effects varied across issues, with party cue effects just around 3 percentage points on issues where most participants knew party positions in advance (also see Bullock Reference Bullock2011, 509). Due to intense media coverage of the collective bargaining, our participants might already have known the (changed) partisanship of the chairman of Local Government Denmark or the bipartisan nature of his role, effectively weakening experimental treatments (Slothuus Reference Slothuus2016). A priori, then, we should expect party cue effects toward the lower end of the estimates presented by Clifford, Leeper, and Rainey (Reference Clifford, Leeper and Rainey2019).

From this perspective, the party cue effects in our experiment, shown in Figure 1, are substantial. Social Democratic voters (top row) expressed strong support for the public employees’ demands in the control group, scoring 0.80 on the index averaging the four opinion items. However, once they received a Social Democratic cue (i.e., their In-Party) that sided with public employers, support dropped by 9 percentage points (rounded) to 0.72 (p < 0.001). Comparing the two party cues, the contrast to the Liberal cue (0.84) was even larger: 13 percent (rounded) of the scale (p < 0.001). Among Liberal voters (bottom row) we see similar party cue effects, although smaller in size. In the control group, Liberal voters expressed slightly lower support for public employees’ demands (0.70 on the index) than Social Democratic voters did, and support was 0.66 when they received a cue from their party to go against the unions’ demands (p = 0.156). Comparing the two party cues, the party cue effect was 5% of the opinion scale (p = 0.047).

Figure 1. Effects of Party Cues on Policy Opinion among Social Democratic (N = 433) and Liberal (N = 325) Public Employees

Note: Opinions cover four key aspects of the conflict: employers’ lockout of employees, how much public employees’ salaries should increase, whether public employees should have a stated right to paid lunch break, and whether teachers should be allowed to renegotiate their work hours, as well as an index of the four questions.

In sum, party cues moved citizens’ opinions with at least the same magnitude as in previous studies conducted on much less personally consequential issues. Even though we exposed respondents to just a few mentions of parties’ positions on a policy where public employees had obvious self-interest at stake, and in a context where union mobilization and news attention peaked, we find party cue effects to be substantial. Strikingly, we find party cue effects of virtually the same size even if we just focus on public employees who expect the collective bargaining would directly affect them financially (see Appendix E). This ability of parties to ostensibly lead partisans to go against their self-interest emphasizes the power of parties to shape opinions and suggests that party cue effects generalize widely.

The Nature of Party Cue Effects: Reversing or Moderating Opinion?

Party cues moved opinion even when self-interest was at stake, but did parties lead public employees to flip their opinion to go against their self-interest? Or did the parties, rather, make public employees dampen their policy demands, leading them to accept a less extreme policy outcome but without taking the employers’ side in the conflict? To grasp the nature of party cue effects on opinion, it is necessary to move beyond merely analyzing average opinion to also study how party cues influence the distribution of opinion.

While there are different ways to estimate distributional treatment effects, we opt for a straightforward, nonparametric approach that imposes no model assumptions on the data. Using the opinion index, we calculated the distribution of opinion when public employees received an In- versus Out-Party cue and, importantly, the difference between the two distributions. This difference directly shows how the mass of the distribution shifts in response to treatment and we simulated sampling uncertainty using bootstrapping.

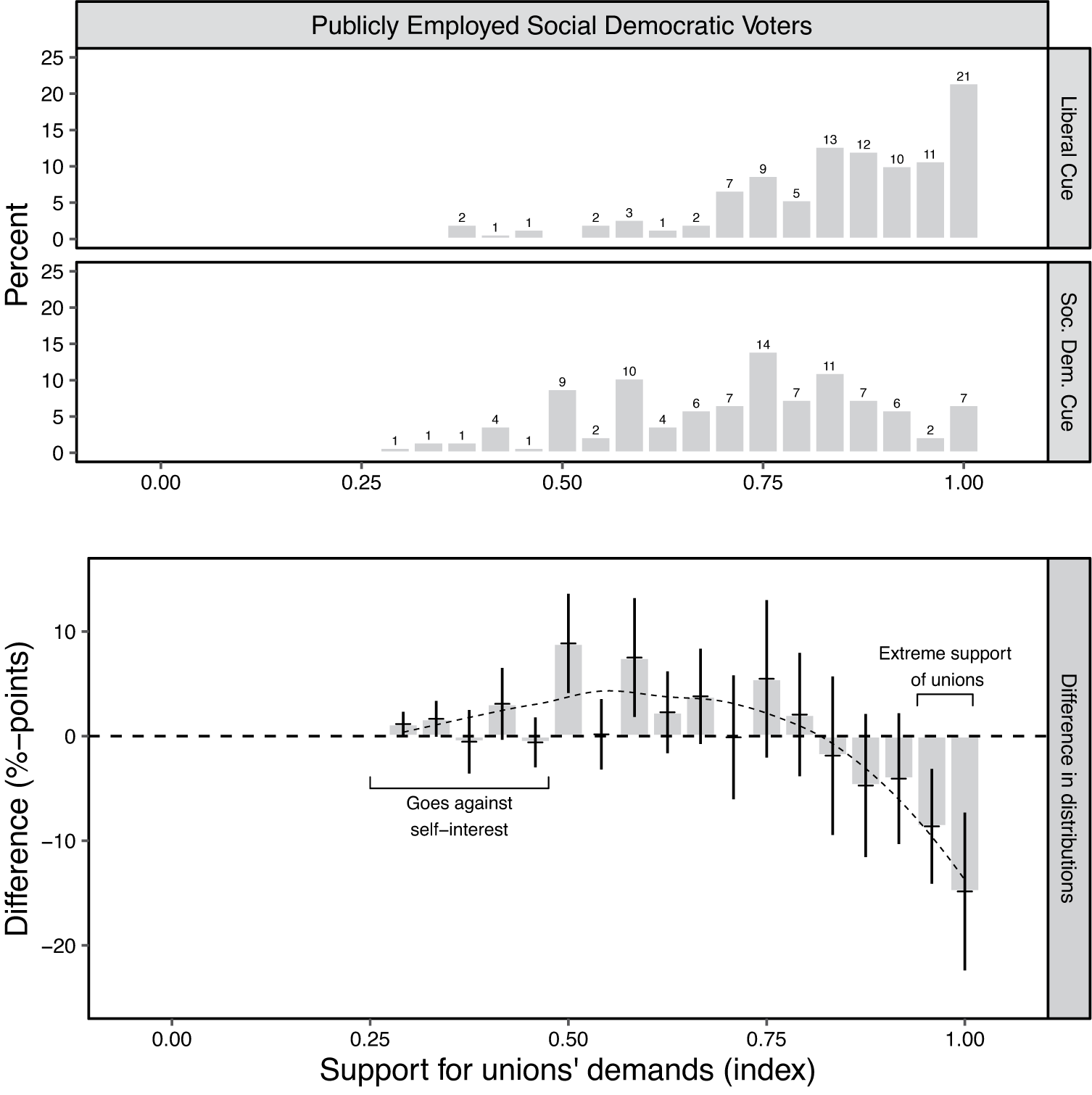

We first look at Social Democrats, the group displaying the biggest opinion change in response to party cues. The upper half of Figure 2 shows the distribution on the opinion index among Social Democratic public employees in the two party cue conditions. The difference in opinion between the two conditions is striking. When exposed to the Liberal cue, Social Democrats expressed extreme support for the unions’ position, with 21% “completely agreeing” with the public employees’ demands on all four opinion questions. An additional 11% responded “completely agree” on three out of four questions and the second-most supportive category on the fourth question. In other words, when receiving the Liberal cue, one third (32%) of Social Democrats expressed consistently strong support for the public employees’ demands. In stark contrast, when they received cues from their own party, only 9% of Social Democrats expressed such extreme support of public employees’ demands. This change at the most extreme end of the opinion scale is striking and, as shown in the lower half of Figure 2, statistically significant. Thus, the In-Party cue dramatically changed the distribution of opinion by tempering the most extreme demands from Social Democratic public employees.Footnote 1

Figure 2. The Distributional Effects of Party Cues among Publicly Employed Social Democratic Voters

Note: The lower panel shows the difference between the two distributions in the upper panel. The vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals that were calculated using bootstrapping (1,000 iterations), and the dashed line fits a LOESS curve through the estimated differences.

Does this mean that the Social Democratic cue could lead partisans to support a policy that went against their self-interest? No. Very few Social Democrats followed their party’s support of public employers and moved to, on average, supporting their policy position. This is indicated by the minimal difference in opinions below the midpoint of the index (0.50) shown in the lower half of Figure 2. Thus, the In-Party cue worked by tempering self-interest and not by leading citizens to go against their self-interest.

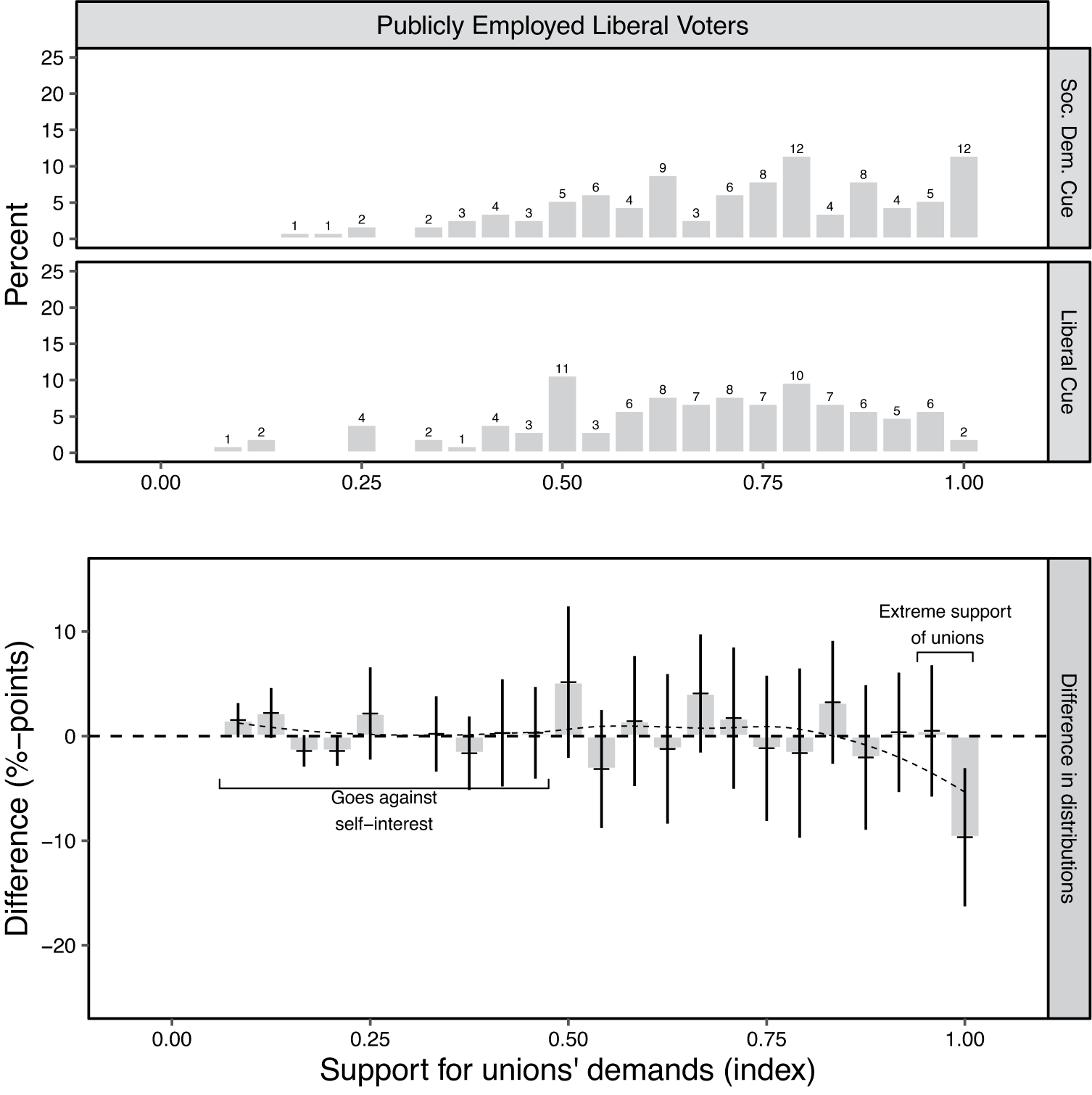

Turning to Liberal voters, we find a similar pattern (see Figure 3). Consistent with the smaller party cue effects among Liberal voters, the change in the distribution of opinion was less dramatic in magnitude than among Social Democrats, but still substantial. Whereas 17% of Liberal public employees expressed one of the two most extreme values on the index in response to the Social Democratic cue, only 8% of Liberals expressed such extreme opinions in response to the Liberal cue. Just like Social Democrats, rather than being led by their party go against their self-interest, Liberal voters responded to cues from their party by moderating opinion and expressing less extreme policy demands. Moreover, this analysis helps explain why we found smaller party cue effects among Liberals than among Social Democrats. As Liberals were less extreme in their initial support of the unions’ position, they could to a lesser extent move toward their party’s position without going against their self-interest. Party cues, at least in the context studied here, appear to work by tempering extreme policy demands—not reversing opinions.

Figure 3. The Distributional Effects of Party Cues among Publicly Employed Liberal Voters

Note: The lower panel shows the difference between the two distributions in the upper panel. The vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals that were calculated using bootstrapping (1,000 iterations), and the dashed line fits a LOESS curve through the estimated differences.

Discussion

Our study advances a long-standing debate in political science about the power of political parties to shape public opinion. Studying a policy issue where citizens were aware that their self-interest was at stake, we found that party cues influenced opinion among publicly employed partisans, even though their party advocated a policy position that clearly went against their self-interest. Strikingly, party cues moved opinion by as much as 13 percentage points—at least as much as in previous studies conducted on issues with much less direct consequence to citizens’ material well-being.

At first glance, this finding might worry scholars concerned that party cues lead citizens to follow their party “blindly” or “mindlessly” in the sense that they support the party’s policy even if it contradicts their interests or values. This would portray citizens as unable to assess what is in their best interest and leave party elites with much power over citizens (Bullock Reference Bullock, Suhay, Grofman and Trechsel2020; Druckman Reference Druckman2014; Freeder, Lenz, and Turney Reference Freeder, Lenz and Turney2019). However, using a novel approach to look more closely at how party cues affected the distribution of opinion—not just average opinion—the second step of our analysis revealed a subtle, yet crucial, point for understanding the nature of party cue effects. While an average treatment effect of 13 percentage points could indicate that parties can powerfully move public opinion, the nature of this effect depends, in part, on how party cues shift the underlying distribution of opinion. As we found, party cues did not lead public employees to go against their self-interest. Instead, party cues worked by tempering the most extreme policy demands among public employees, leading them to take a more moderate position on the issue. This is a remarkable finding, as on other issues, with self-interest less clearly at stake, parties have been able to reverse opinions (Slothuus and Bisgaard Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021a).

More substantively, our approach allowed us to discover a previously underappreciated ability of parties to temper the pursuit of self-interest among citizens with the most extreme policy demands, without leading these citizens to express an opinion that went directly against their self-interest. Parties acted by moderating—not fueling—extreme opinion, potentially paving the way for compromise by making citizens’ opinions less extreme. Parties, depending on the nature of elite partisan conflict, might thus hold the potential to help us reveal “better-informed versions of ourselves” (Bullock Reference Bullock, Suhay, Grofman and Trechsel2020, 129).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000332.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YXMGMU.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Asmus Leth Olsen for encouraging us to conduct this study and David Broockman, John Bullock, Scott Clifford, Peter Thisted Dinesen, Jamie Druckman, Ryan Enos, Frederik Hjorth, Martin Vinæs Larsen, Howie Lavine, Gabe Lenz, Matt Levendusky, Lilliana Mason, C. Dan Myers, Asmus Leth Olsen, Mathias Osmundsen, Michael Bang Petersen, Mike Sances, Rasmus Skytte, Kim M. Sønderskov, Mathias Tromborg, Lene Aarøe, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and advice. A preliminary analysis of this data occurred in Bisgaard and Slothuus (Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2019). The authors are listed in reverse alphabetical order.

FUNDING STATEMENT

We acknowledge support from Independent Research Fund Denmark (DFF-4003-00192B) and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 865956).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.