Introduction

The Viking Age in the West is viewed in national and ethnic terms by academic and popular audiences as a ‘colonising’ migration of Scandinavians, who went on to form conquering elites or whole societies across the North Atlantic and Europe. Conventionally taken to begin with raids in the AD 790s, its causes have been sought primarily within Scandinavia, in relation to endogenous economic, political, environmental and social stresses. Territorial expansion is assumed to have succeeded the pattern of raiding in both time and location, and to have occurred first on the nearest and most convenient landfalls. Areas of Britain that have upheld the strongest Scandinavian cultural connections into modern times—notably Orkney and Shetland—are often viewed unquestioningly as the locations of the earliest and most vigorous Viking settlement. There are, however, grounds for challenging this sequence of assumptions, and for redefining the Viking Age as a sporadic, opportunistic and chaotic series of events and unforeseen cumulative impacts. The limited contemporaneous evidence, it is argued below, has been embellished and reworked retrospectively into a ‘national conquest’ narrative by later historical and literary sources seeking to emphasise the power and lineage of medieval dynastic states. This stance was then continued into modern scholarship during the Scandinavian nationalist revivals of the nineteenth century. The Western Viking Age is not a fiction, but, in its currently understood form, is a distorted concept, given a spurious and artificial coherence by later accounts. This legacy has proved difficult to overcome.

The early Viking Age: a ‘bolt from the blue’?

The view of the Viking Age as an invasion of Europe by the Scandinavian nations remains so embedded in modern perceptions that the co-editor (Brink Reference Brink, Brink and Price2008: 4) of a recent major summative publication felt able to introduce it thus:

from 800 to around 1050 […] Norwegians in particular controlled and colonised the whole of the North Atlantic […] Especially Danes but also Norwegians and Swedes ravaged and had an impact on the political and social development of England and parts of France. Swedes travelled eastward.

The search for expatriate Scandinavians and their indigenous cultural traits remains an undimmed obsession for archaeologists, biologists and historians. This is despite a growing awareness through current research and debate (e.g. Baastrup Reference Baastrup2014; Eriksen et al. Reference Eriksen, Pederson, Rundberget, Axelsen and Berg2015) that the evidence is far more complex, nuanced and ambiguous than could reasonably serve such a purpose. Causal factors behind this multi-national, but curiously simultaneous phenomenon, have been sought mainly within Scandinavia itself. A demographic surplus of young males (e.g. Barrett Reference Barrett2008), advancing ship technology, opportunities for engaging in slavery, land-hunger, and commodity trading (e.g. Baug et al. Reference Baug, Skre, Heldal and Janssen2018) have all been given varying degrees of credence. The widely differing social and environmental topography of Iron Age Scandinavia is often elided into a single causative background. The Viking Age is usually considered to have ‘begun’ in the later eighth century AD, when Western European sources begin to describe and attribute raids in some detail, and to have ‘ended’ in the mid eleventh century.

There is no doubt that sporadic raiding captured the fears and, to some extent, the imaginations of Western European Christian writers in the 790s; the raid on Lindisfarne in 793, conveyed most vividly by Alcuin's letter to Ethelred, King of Northumbria, shortly after the event (Whitelock Reference Whitelock1979: 842), is the quintessential marker for the start of this new period of danger. But to what extent was the Viking Age a ‘bolt from the blue’ or, alternatively, a symptom of existing behaviour turning violent in the context of systemic social and economic breakdown? Scandinavians were far from strangers to Western Europeans. Cultural contacts pre-date the Romans and were vigorous in the mid first millennium AD—as exemplified by similarities between the high-status ship burials at Sutton Hoo, England, and at Vendel and Valsgärde, Sweden. Scandinavians were busily—and profitably—involved in the North Sea trading network between England, Frisia and Francia, which reached its apogee in the mid eighth century. The earliest growth of the trading town at Ribe, Denmark, for example, dates to AD 705–710 (Feveile Reference Feveile2006). Yet as a temporary period of trade-driven prosperity around the southern North Sea faded in the later eighth century, events around its fringes took a chaotic turn.

The ‘southern route’

A recent historical survey of the early Viking Age (Downham Reference Downham2017) reminds us that Lindisfarne was not the first, nor even necessarily the most important, of the early Viking attacks on Britain. In AD 792, the Mercian King Offa strengthened the coastal defences of Kent, and the first recorded Scandinavian attack on British soil took place in 789 on the south coast of Wessex, at Portland in Dorset (Whitelock Reference Whitelock1979: 180). Even while Charlemagne lived, Vikings harried the fringes of the Carolingian Empire (Gautier Reference Gautier, Buti and Hrodej2016), attacking Aquitaine in 799 and Frisia in 809. After his death in 814, Vikings began to menace Francia in earnest (Nelson Reference Nelson and Sawyer1997). At this time, the geographic emphasis of their activity was on the southern North Sea and around the English Channel. Francia bore the brunt of attacks in the early ninth century, but a concentrated presence in England began with the overwintering of a Viking army in Thanet in 850. By contrast, evidence for raids on the far north of Britain is elusive. There are no documented cases of attacks on northern or eastern Scotland, the Outer Hebrides or the Northern Isles. Archaeologists claim to have identified an unrecorded Viking attack on a Pictish monastery in north-eastern Scotland, at Portmahomack (Carver Reference Carver2008: 80; Carver et al. Reference Carver, Garner-Lahire and Spall2016: 256–60), based on skeletal evidence for blade injuries observed in a small number of inhumations, the destruction of buildings and industrial areas by fire, and the apparent desecration of Christian symbols in the form of broken pieces of stone crosses. This claim, although persuasive, remains debatable: this evidence could have a number of alternative and indeed unconnected explanations, including inter-communal violence, accidental fire and the re-use in different contexts of debitage from stone carving.

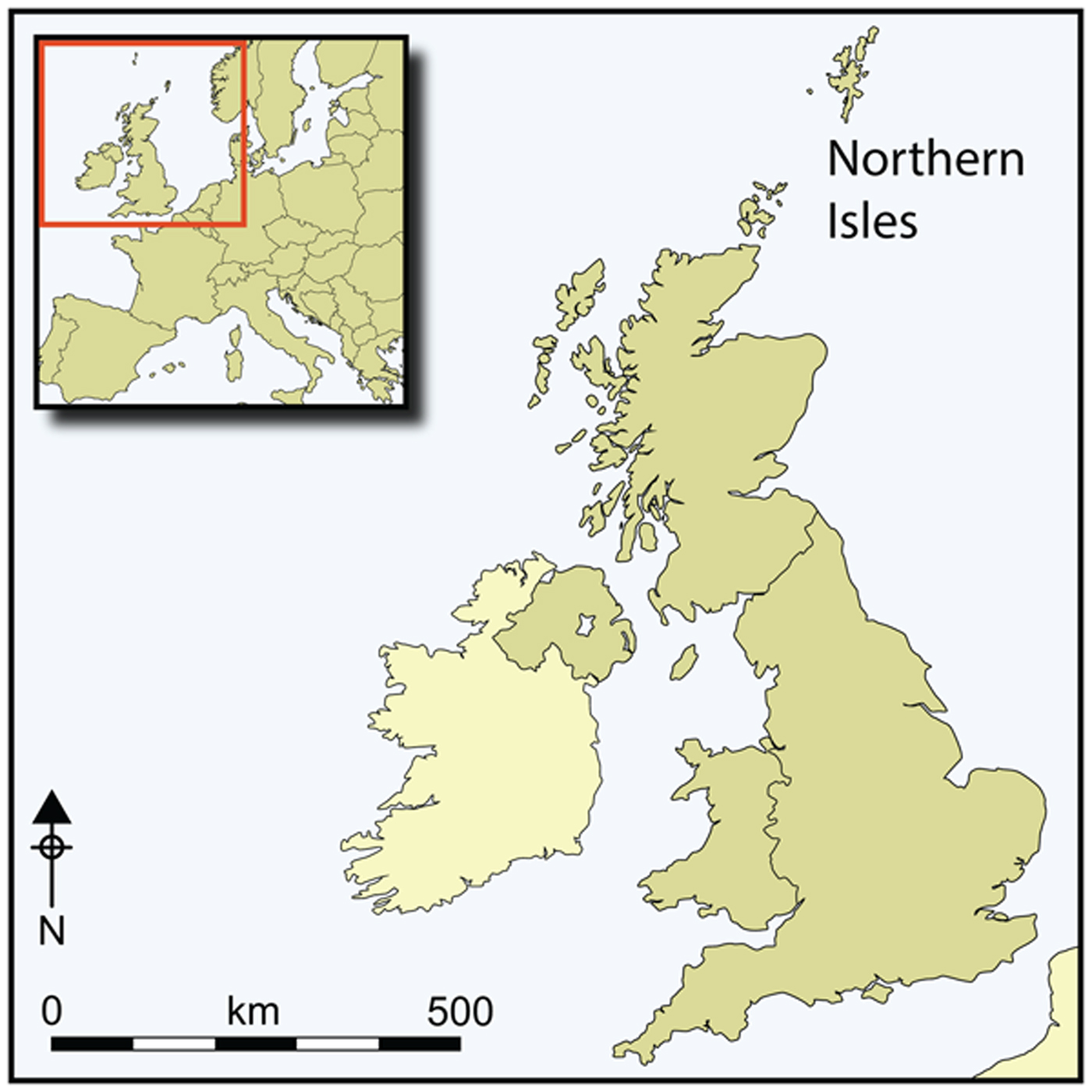

The attack on the monastery at Lindisfarne in AD 793 could have been an opportunistic raid, following a chance landfall while heading south. Navigating the North Sea by eye from the Skagerrak to Francia can involve making visual contact with Britain due west of southern Scandinavia, and tracking the coastline southwards (thus avoiding the shoals and lee shores of the continental side) towards the inward-funnelling narrows between East Anglia and the Low Countries. Sighting Lindisfarne from the sea therefore makes more sense on an expedition headed south, rather than one aimed at the far north. The near-simultaneous initial phase of Viking raids on Irish monasteries and on Iona, from 795–806, also requires explanation. Traditionally, these raids are assumed to have come from the north, but could these, in fact, have been northern outliers of raiding activity coming through the Irish Sea from areas farther south? A proposed ‘southern’ emphasis in the geographic development of early attacks and connections is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Map of early Viking activity in the West (arrows indicate the sequence of expansion).

Cultural convergence in Francia, England and Ireland

Historical commentators of the eighth and ninth centuries were more concerned about the pagan religion of the invading Vikings than with their ethnicity. The former was brittle and short-lived, whereas the latter proved almost infinitely malleable, as their campaigns engaged with divergent political structures, peoples and landscapes across Western (and Eastern) Europe. Viking corporate organisations were militarised, but were permeable to local recruitment and intermarriage. Current research into Viking war-bands has illustrated the heterogeneity of their origin and emphasised their shared cultures and mentalities (e.g. McLeod Reference McLeod2014; Raffield Reference Raffield2016). This research confirms that a definition of Vikings as actors—pirates or adventurers—rather than as ethnic stereotypes, continues to be valid. By no means all ‘Viking’ settlers were necessarily ethnically Scandinavian in origin. The growth in the study of isotopes from inhumations in Viking cemeteries is illuminating the complex and varied composition of settled groups (e.g. Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Grimes, Buckberry, Evans, Richards and Barrett2014). Viking language, biology (DNA), religion and material culture rapidly transformed in the context of new lands and cultural contacts. Some Scandinavian elements persisted, but the extent to which others were discarded, or isolated as heirlooms in favour of the adoption of contemporaneous cultural expressions in new lands, is remarkable. The Vikings who invaded England and Ireland in the ninth century bore with them the trophies of recent campaigns on the continent, as well as the portable wealth of developing pan-European trading networks, as demonstrated by the range of material in their silver hoards (e.g. Graham-Campbell Reference Graham-Campbell2011). Their biology must surely have reflected these intermediate circumstances. Lifespans were relatively brief; the five decades between 790 and 840 gave plenty of time for the early raiders’ descendants to have grown up entirely outside Scandinavia. Many of the weapons and personal ornaments displayed in furnished graves in Britain and Ireland were of Frankish origin (Thomas Reference Thomas2012). In their recent comprehensive study of Viking graves and grave-goods in Ireland, Harrison and Ó Floinn (Reference Harrison and Floinn2014: 76–77) remark on the imported swords found within the graves: “As the preponderance of possible Carolingian forms demonstrates, however, these swords were not necessarily imported from Scandinavia”.

Weapons in insular Viking burials were accompanied by a range of locally made objects, such as Hiberno-Norse ringed pins and conical shield bosses (see Figure 2). There were some imported Scandinavian objects—notably variants of the oval brooch—but these tend to be somewhat earlier in date than other elements in the same graves (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2010: 72–73). In urban and rural settlement contexts, too, the proportion of imported Scandinavian objects is surprisingly low, and Scandinavian naming habits and territorial distinctiveness were intricately linked to pre-existing local traditions. There are, nevertheless, numerous parallels found in Scandinavia for these objects and assemblages (Wamers Reference Wamers, Clarke, Ní Mhaonaigh and Floinn1998; Aanestad Reference Aanestad2015). The extent to which Scandinavia received incoming cultural practices (and, indeed, people) during the Viking Age—as opposed to exporting them—probably has been greatly underestimated. In tracking the Viking presence outside Scandinavia, we are searching for a fast-changing and adaptive intrusive population element. From the earliest attacks onwards, this was not a ‘colonial’ Scandinavian imprint, but already had become something hybrid and subject to ongoing transformation, while retaining some strategic cultural allusions to a real or imagined homeland. Continuing to search for an untrammelled Scandinavian archaeological heritage as a means of identifying the Viking presence will probably prove to be a fruitless and misinformed endeavour.

Figure 2. Objects from Viking graves at Kilmainham-Islandbridge, Dublin, 1845 (© National Museum of Ireland). Only five of the sixteen objects depicted in this plate (one of a series of watercolours by James Plunket) can be securely provenanced to Scandinavia (for the catalogue with object dimensions, see Harrison & Ó Floinn Reference Harrison and Floinn2014).

The Northern Isles

Orkney and Shetland are often described as the earliest staging posts for Viking settlement in Britain. Their geographic proximity to Norway has been much remarked upon, along with their predominantly Scandinavian place names and cultural affinities (e.g. Crawford Reference Crawford1987). Orkney and Shetland were the last sovereign additions to the British Isles, having been impignorated (pledged or pawned) by Denmark-Norway to Scotland in AD 1468–1470. The Orkneyinga Saga (composed in Iceland c. AD 1200) appears to secure their historical pedigree as Norwegian colonial possessions, by describing how they were taken over, initially by pirates (some of whom were Danish), and then by the Norwegian earls of Møre, during the reign of Harald Hárfagri (Finehair), around 870. The saga says nothing of their pre-Viking inhabitants. While there may be a grain of truth to this claim, the context in which the saga was written must be considered. It was composed at a time when Norwegian claims of suzerainty over the North Atlantic territories were being pressed energetically by supporters among writers and poets in Iceland. Orkneyinga Saga formed part of Snorri Sturlason's inspiration for writing Heimskringla—his definitive account of Norwegian royal authority—and helped to give historical ballast to calls for the union of Iceland and Norway, which came about later in the thirteenth century.

The strength of Orkney and Shetland's cultural connections with Scandinavia has arguably clouded scholarly perceptions of their early Viking Age. A date of c. 800 for the Viking take-over has become orthodox, although this is based on little more than guesswork. Archaeological confirmation of an early and dominant Viking presence has remained elusive. The Viking influence or threat has been invoked indirectly, for example, through the burial c. 800 of an Insular-style hoard under a chapel floor at St Ninian's Isle, Shetland. There may, however, have been other reasons for this deposit; although concealed, its position was hardly inconspicuous, being under an upward-facing cross-marked slab and central to the chapel (Barrowman Reference Barrowman2011: 203). Little or no evidence has been identified for the destruction or raiding of pre-Viking churches or settlements in the Northern Isles. No burials, longhouses or hoards indicative of early Scandinavian dominance have been dated conclusively to before the later ninth century. Indeed, most are from the mid tenth century or later. A phase of possible early Viking re-use of earlier structures has been recognised in recent excavations of multi-period settlements, notably at Old Scatness, Shetland (Dockrill et al. Reference Dockrill, Bond, Turner, Brown, Bashford, Cussans and Nicholson2010), and Pool, Sanday, Orkney (Hunter et al. Reference Hunter, Bond and Smith2007). This interpretation may also be applied retrospectively to Buckquoy, Orkney (Ritchie Reference Ritchie1977). Pre-Viking house structures of Pictish cellular form developed some possible Scandinavian traits, such as long central hearths, and material culture and dietary changes point to the possible presence of incomers (Bond & Dockrill Reference Bond, Dockrill, Turner, Owen and Waugh2016). Dating these domestic adaptations coherently to the earliest historical period of Viking involvement, however, remains problematic (e.g. Brundle et al. Reference Brundle, Lorimer, Ritchie, Downes and Ritchie2003). Their nuanced and fleeting nature suggests convergence with, rather than conquest of, the pre-Viking inhabitants; indeed, possibly (dare one say it?) some element of permission from, or even subjection to, local leaders.

No such doubts concerning early dates apply to the Viking presence in Ireland. Here, we are confronted by an almost equal and opposite conundrum, with furnished ‘warrior’ burials in Dublin giving surprisingly early radiocarbon dates of c. 800 (Simpson Reference Simpson and Duffy2005; for a critique, see Griffiths Reference Griffiths2010: 76). This early dating contradicts the majority of their associated finds, which would normally be dated stylistically somewhat later; indeed, the Viking take-over of Dublin is first attested historically in 841.

What does, however, characterise the growth of Viking culture in the Northern Isles (and other parts of Scotland), once it becomes more widely recognisable in the tenth century, is an undeniably strong admixture of Hiberno-Norse cultural forms. The author's excavations of a tenth- to twelfth-century Viking settlement at the Bay of Skaill, Orkney, show a preponderance of Irish Sea forms among the combs and dress ornaments. There are also Rhineland and French allusions among the glass objects and pottery (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Harrison and Athanson2019). The nearby Skaill Hoard, found in 1858 and dated to AD 960–980, has strong elements of ‘Irish Sea’ ornamental style (Griffiths Reference Griffiths, Barrett and Gibbon2015; Graham-Campbell Reference Graham-Campbell, Griffiths, Harrison and Athanson2019). By contrast, a more exclusive dominance of Norwegian contacts appears somewhat later in these islands, as the economy changed towards cod fisheries after 1000 (Barrett Reference Barrett2012). The Hiberno-Norse contacts evident in the earlier archaeology may help explain the (re)appearance of Ogham script in the Northern and Western Isles during the Norse period (e.g. Forsyth Reference Forsyth, Ballin-Smith, Taylor and Williams2007, Reference Forsyth and Barrowman2011; see also Griffiths Reference Griffiths2010: 155). These contacts have parallels in historical sources, where a long and otherwise inexplicable obsession with Irish politics seems to have troubled the earls of Orkney. Earl Sigurd, for example, famously died carrying the Raven banner at the Battle of Clontarf, near Dublin, in 1014.

Implications for the Norwegian take-over of the North Atlantic

Emerging from the observations above is a hypothesis that the Northern Isles of Scotland were relative latecomers to the Viking world, and that they received much of their initial impetus as such from Ireland, Britain and Francia. The reproduction of Viking society in the North Atlantic territories surely drew in Irish, Frankish and British elements—particularly women—changing their heritable biology. Studies of mitochondrial DNA in Iceland (Helgason et al. Reference Helgason, Sigurđardóttir, Gulcher, Ward and Steffánsson2000) point towards a significant ‘Celtic’ admixture, such as could only reasonably have resulted from a scenario as painted here. Hybrid Viking groups from Ireland, Britain and the Northern Isles are potentially responsible for populating the islands farther to the north and west at least as much as was direct immigration from Scandinavia itself.

A theory of a dominant southern route bringing early Viking influence via the English Channel and the Irish Sea towards the North Atlantic will inevitably find its sceptics and detractors. It appears, for instance, to be contradicted flatly by the Icelandic sagas, which stress Norway's dominance, although reasons for questioning this have been advanced above. There was undoubtedly some Norwegian trade and migration, and it would be wrong to suggest otherwise. Yet viewing Scandinavia as the only, or principal, coloniser and exporter of people (and not a receiver of these) must surely now be open to question. In doing so, one faces head-on the accumulated weight of almost two centuries of scholarly tradition, beginning with J.J.A. Worsaae in the 1840s (Worsaae Reference Worsaae1852), which has sought to identify and classify the spread of Danish and Norwegian influence in the West by reference to Scandinavian museum collections, principally in Copenhagen and Oslo. An orthodoxy that these are the core reference materials for understanding the Viking Age beyond Scandinavia grew with the rise of modern Norwegian nationalism in the early twentieth century, as reflected in Haakon Shetelig's Viking Antiquities series (Shetelig Reference Shetelig1940–1954), and remains influential. There is little evidence of any ‘national’ quest behind the early Viking expansion; arguably, this has been imposed retrospectively to serve later political ends. Rethinking the early Viking Age in the West brings new questions as to the origins and causes of the Viking phenomenon as a whole, some of which perhaps lay outside Scandinavia, and thus prompts fresh debate.