The problem of terminology

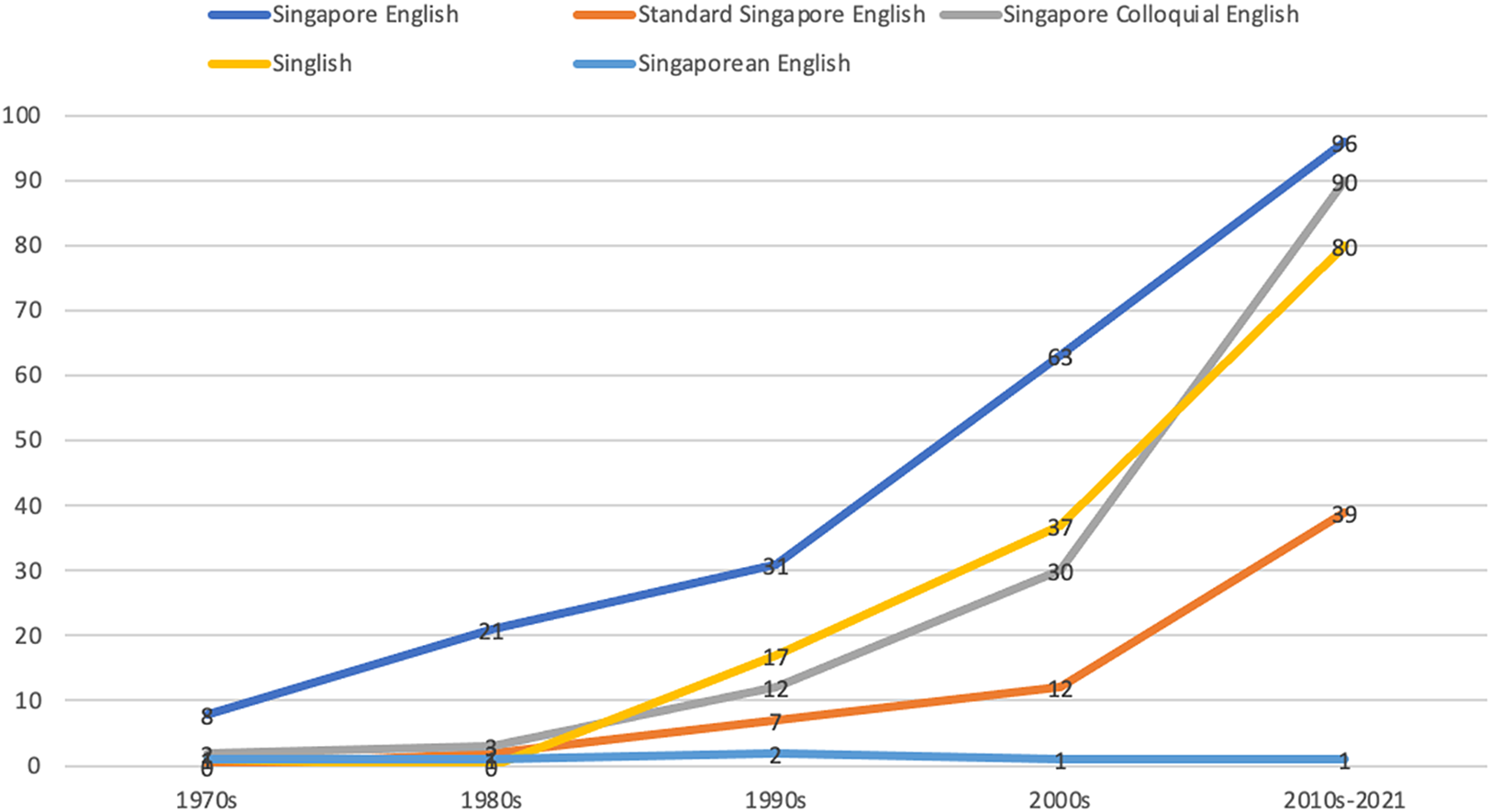

When it comes to Englishes in Singapore, two terms come to the fore: Singapore English, and Singlish. As part of the methodology and motivation for this paper, I compiled 500 published works on Englishes in Singapore ranging from the 1970s to 2021. These published works include monographs, edited volumes, chapters in edited volumes, and articles in major peer-reviewed journals. 85% of the 500 publications used the term Singapore English, 27% of them had Singlish, and only a mere six publications (around 1%) used the term Singaporean English. One would expect that for a term that speaks of and to the being of the nation, the term Singaporean English would certainly be used with far more frequency. This is especially so when there is in fact nothing morphologically awkward in attaching the suffix -ean to ‘Singapore’. There are immensely more examples of Englishes around the world that have the suffix (or its near equivalent) than those without (American, Tanzanian, South African Englishes are just some of numerous examples); and the two well known Englishes that remain suffix-free are New Zealand English and Hong Kong English, which we can explain by way of a morphological misfit: the -er suffix does sound rather awkward. Since Singapore does not have this problem, why then does Singapore English resist the suffix -ean?

There is a wealth of literature on Englishes in Singapore. According to Tan (Reference Tan, Hashim, Leitner and Wolf2016: 69), Singapore English ‘is one of the most extensively researched and well-documented institutionalised second-language varieties of English’. With the proliferation of research in this area, scholars have also used a plethora of terms describing what they believe are the different registers or varieties of English spoken in Singapore. In some cases, the terms are rather straightforward. The words standard, and colloquial, are added before ‘Singapore English’ to indicate the variety described. Foley (Reference Foley1988), Pakir (Reference Pakir1991), Bolton and Ng (Reference Bolton and Ng2014), for example, make a clear distinction between ‘Standard Singapore English’, abbreviated as SSE, and ‘Colloquial Singapore English’ (CSE) or ‘Singapore Colloquial English’ (SCE). This convention has been followed faithfully by most scholars, and some researchers go further by explaining that when they use the term Singapore English, they are referring to SSE (e.g. Leimgruber, Reference Leimgruber2013; Ng, Cavallaro & Koh, Reference Ng, Cavallaro and Koh2014; Ziegeler, Reference Ziegeler2015). When it comes to Singlish, it has also become common practice in the field for scholars to make qualifications upon first mention of the term, as can be seen in this example: ‘For Singaporeans it is very natural to switch between Singapore Standard English (SSE) and Singapore Colloquial English (SCE), namely, Singlish’ (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Cavallaro and Koh2014: 398). Also common is the practice of stating the similarity between Colloquial Singapore English and Singlish and explaining why they prefer not to use the term Singlish (e.g. Gupta, Reference Gupta1994; Lim & Foley, Reference Lim, Foley and Lim2004). As if to make things even more complicated, other scholars like Low (Reference Low, Low and Azirah2012) and Alsagoff (Reference Alsagoff, Lim, Pakir and Wee2010a) throw ‘International Singapore English’, and ‘Local Singapore English’ into the mix, expanding the list of names used to describe Englishes in Singapore. Despite the terms used, what is obvious is that under this plethora of terms lies a distinction that is fundamentally binary in nature: standard vs. colloquial, Singapore English vs. Singlish, local vs. international. And it bears reminding that even within this binary distinction, the term Singaporean is hardly ever used.

These nomenclatures are very curious indeed, and in fact raise some questions that this paper will attempt to answer: why are the terms Singapore English and Singlish more in currency as compared to Singaporean English? In order to answer that, two other questions need to be asked: namely, how do these terms come about? And, how have scholars conceptualised Englishes in Singapore? I will answer these questions by presenting evidence from archival research of local newspapers, starting from the 1800s, to trace when these terms reached public consciousness, and how the public has understood them. I will also present an overview of how linguists have used these terms in their writing on Singapore(an) English and Singlish, and using that to trace their ideologies and the way they shape the construction of these languages. Through the analysis, I propose that we can see two major waves of past research. The first wave started in the 1970s, which saw scholars making no distinction between Singapore English and Singlish. The second wave started in 1990, which marked the start of a long period of scholars naming Singlish as Colloquial Singapore English, and describing it as different from the standard. Through the analyses of how Singapore English and Singlish have developed in both academic and public discourse, I will show that the nomenclatures, though curious, are no coincidences, and that they bear the signs of what these languages represent to the people.

Early Press Appearances

It was reported that by the time the British East India Company claimed Singapore as a British trading post in 1819, this tiny Southeast Asian island was inhabited only by a few families of Orang Laut (‘sea people’), a small Chinese settlement of pepper and gambier cultivators, and about 100 Malay fishermen from Johore (Bloom, Reference Bloom and Kapur1986: 349). It would not be wrong to say that the English language reached the Singaporean shores only with the arrival of Stamford Raffles and his entourage in 1819, and that early publications in English, if any, were meant for consumption by the British, and not the indigenous settlers. In fact, according to the available resources at the National Archives of Singapore, local publications in English started in 1827, the first of which was the Singapore Chronicle and the Commercial Register.

Singapore was very much a classic colonial outpost. Not unlike what one would see in other colonised lands (see Schneider, Reference Schneider2007 on postcolonial examples; and Faraclas et. al., Reference Faraclas, Walicek, Alleyne, Geigel, Ortiz–López, Ansaldo, Matthews and Lim2007 on creoles), English was very much restricted only to the European settlers and a select elite who were connected to the British colonial administration in the 1800s. Raffles’ idea was ‘to improve the standard of education in the native languages, and to give in addition some instruction in English and in western science to those who seemed best able to profit by it’ (Hough, Reference Hough1933: 168). Therefore, while the British administration did set up the English-medium Raffles Institution, English education was made available only to the children of European settlers and a tiny number of locals who could afford it (Gupta, Reference Gupta, Foley, Kandiah, Bao, Gupta, Alsagoff, Ho, Wee, Talib and Bokhorst–Heng1998). Meanwhile, the Malays attended vernacular schools (Gupta, Reference Gupta1994: 34), and Chinese settlers who migrated from Southern China set up clans which saw to the establishment of Chinese schools running classes in their respective Chinese languages (Koh, Reference Koh2006). Similarly, the Indian community, primarily migrants from South Asia, also ran schools in their vernaculars. The spread of English was very much restricted within an elite group, and English was therefore not accessible for the majority of population. If there was such a thing as ‘Singapore’ or ‘Singaporean’ English, it would not have been in the 1800s.

The local newspaper archives give us a clue to the development of Englishes in Singapore. Figure 1 shows the appearances of the terms Singapore English, Singaporean English, and Singlish in local newspapers, beginning in 1827.

Figure 1. Appearances of the terms Singapore English, Singaporean English, and Singlish in local newspapersFootnote 1 [graph generated by www.eresources.nlb.gov.sg]

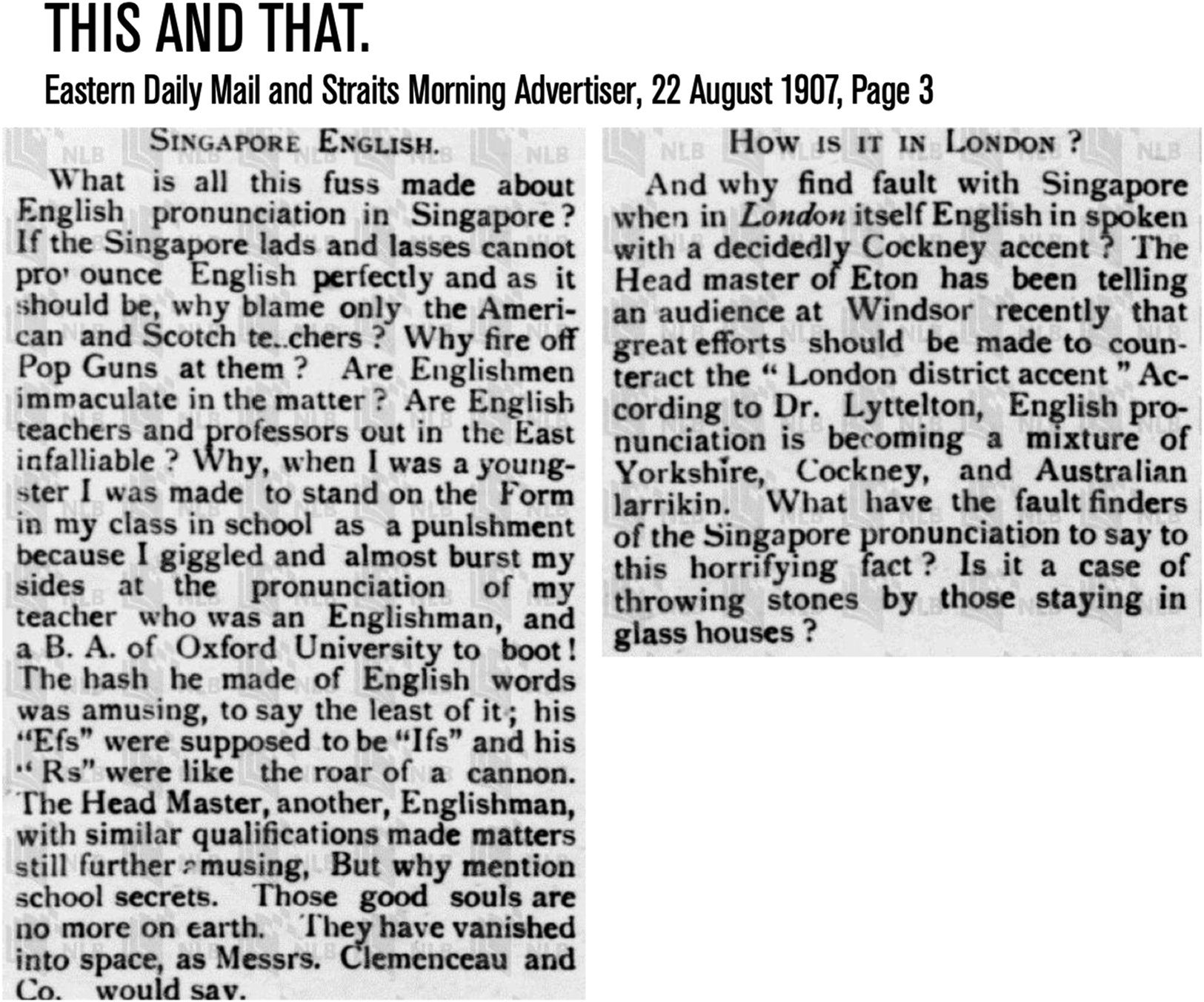

As can be seen in Figure 1, Singapore English was very much more present in the public consciousness as compared to Singaporean English and Singlish, and certainly made its appearance in the local newspapers before the latter two. And even so, the use of these terms, particularly Singapore English, started to spike in the 1970s, and I will discuss this later. In any case, the first time any of these terms was used in the local newspapers was in 1907, and that was when Singapore English was first mentioned. This came 88 years after the arrival of the British. An excerpt of the article can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. First appearance of the term Singapore English in Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, 22 August 1907

The entry in Figure 2 is one of several short vignettes on Singaporean sights and scenes, written by a person named X. Y. Z. One could surmise, from the entry, that X. Y. Z. was possibly a Singaporean who received not just an early English education in a local English school, but was also able to travel to England and had a fair amount of knowledge about England. X. Y. Z. had ‘Englishmen . . . out in the East’ as teachers and professors, and was also able to compare English pronunciation in Singapore to the Cockney accent in England. A few important points can be raised with regard to this entry. Firstly, even though X. Y. Z. went to an English school with Englishmen as teachers, the type of English that was taught was not entirely British. As suggested by X. Y. Z., the supposed ‘English pronunciation’ problem was blamed on the ‘American and Scotch teachers’. This falls in line with Gupta's (Reference Gupta, Foley, Kandiah, Bao, Gupta, Alsagoff, Ho, Wee, Talib and Bokhorst–Heng1998) description of schools in the early 1900s where, while the British did serve as teachers in the local English schools, many of the other teachers were in fact not British, but Portuguese, Irish, American, German, French or Indian in origin. And this brings us to the second point, and that is the nature of this ‘Singapore English’ in 1907. What X. Y. Z. referred to as ‘Singapore English’ was English spoken by ‘Singapore lads and lasses’ with a non-British, Singaporean accent. Coupled with the fact that the English teachers and speakers came from diverse backgrounds, English would have undergone some form of dialect-levelling (Schneider, Reference Schneider2007) during this time. What we see here in 1907, with the first appearance of the term Singapore English, is therefore a formation of a distinctly different accent, created when one had a pool of local English learners taught by a melting pot of English-speaking teachers from all over the world, possibly marking the beginning of what we now know as Standard Singapore English.

While X. Y. Z. sounded like an early champion of a local variety of English, not just by coining the term Singapore English, but also pushing for the acceptance of a local accent, this same sentiment was not shared, particularly by the British themselves. In 1919, someone who signed off as ‘A Britainer’, wrote a letter to the editor in the Straits Times to complain about the ‘Singapore English’ he was ‘treated to’. For the British, if Singaporeans spoke English, they spoke only bad English. Thereafter, it was a long silence for 32 years, for there was no mention of the term Singapore English (or any other related terms) in the local newspapers until 1951.

This silence coincided with the period H. R. Cheeseman was Superintendent of Education, Johore (which then included Singapore). Cheeseman was in office for over 20 years, from the 1920s–40s. Cheeseman was a firm believer of vernacular education and did little to push for English education for the local population. It was no surprise therefore that the English language was not developing in the local ecology since few were given English education. It was not until the mid 1930s that there was some talk about educating the local populace in the language. This was driven in part by Victor Purcell, a British colonial servant, who for several years made public his proposal to have ‘Basic English’Footnote 2 as ‘the solution’ to ‘the Babel of Tongues in Singapore’ (Malaya Tribune, 1935), and a ‘way out of trouble’ (Straits Times, Reference Purcell1937). The problem with Singaporeans was not Singapore English, but that they did not speak English!

For Purcell, Singapore's linguistic woes were due the multitude of languages the locals spoke. In ‘Polyglot Port: Singapore Salvo III’, published in the Straits Times on 28 March 1937, Purcell opened his article with this line: ‘There is, we believe, no record of the number of tongues spoken at the original Babel but we have an idea that if the truth were shown Singapore would be found to have put its ancient prototype into the shade’. As the long article went on to describe the complexity of the linguistic ecology of the early 1900s Singapore, it became clear that Purcell saw societal multilingualism with little mutual intelligibility across speakers as a problem. Problem aside, what was also apparent in the multilingual Singapore that Purcell described was that there was heavy language contact, as the need to communicate across linguistic groups also led to linguistic borrowing across local languages, and also between English and the vernaculars. Figure 3 shows a little extract from Purcell's article describing linguistic borrowing in Singapore then.

Figure 3. Short excerpt of Victor Purcell's article, ‘Polyglot Port: Singapore Salvo III’, published in the Straits Times on 28 March 1937

Some of the borrowings described in Figure 3 are still used in what we know of as Singlish today. This could be the early signs of Singlish, lending credence to Tan's (Reference Tan2017) model in explaining how Singlish came about.

Little went on in the next 35 years, and while the term Singapore English was mentioned sporadically during this period, most of the discussions centered on improving English language education for the local population. It would not be inaccurate to say that there was little public attention on the local variety of English, and if it existed, it was most certainly developing in the background, and not a subject of intense public discussion.

1975: The year everything changed

If the public silence on Singapore English was palpable over the large part of the 1900s, the chatter on this topic in public discourse was positively deafening, starting in 1975 and getting increasingly louder year on year. Besides reporting on the government's initiatives and plans on the English language in Singapore, the local newspapers also covered proceedings of local linguistics conferences and visits by high-profile linguists such as Randolph Quirk, John Platt, and Michael Halliday. Unsurprisingly, there were countless letters and opinions sent in by the concerned public. By the late 1970s, there were at least 100 articles written in the local newspapers using the term Singapore English, and by the late 1980s, the number more than doubled.

What was the most remarkable in 1975 was that the term Singlish appeared for the first time, in a little snippet named ‘Chandy's Singapore’, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. First appearance of Singlish in New Nation, 20 July 1975

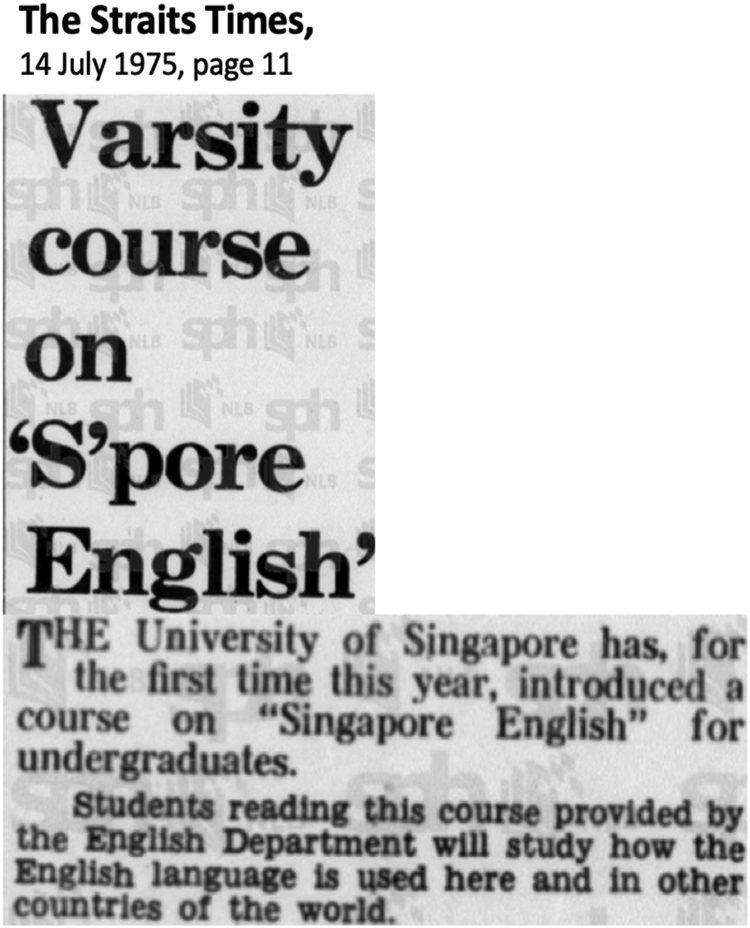

As apparent in Figure 4, the appearance of Singlish coincided with the launch of a course entitled ‘Singapore English’ at the National University of Singapore. Figure 5 shows a short excerpt on the report on the launch of the course.

Figure 5. Short excerpt on the report of the launch of the course ‘Singapore English’ at the National University of Singapore in the Straits Times on 14 July 1975

The fact that the launch of a university course on ‘Singapore English’ made news highlighted two things. For one, that there was a varsity course on Singapore English was a novelty, perhaps almost incredible, and therefore required justification. The report in the Straits Times on 14 July 1975 explained how the course was about the way ‘the English language is used here and in other countries of the world’. And as if to give the course more legitimacy, the journalist made sure to include a line saying that the course would be taught by ‘a woman lecturer, a specialist in Linguistics, [who] just returned from England’.

And the novelty aspect was played out in Chandy's (1975) little snippet. Chandy expressed incredulity at the news: ‘What?’ Chandy asked, and to which he stated rhetorically, ‘Singlish lah!’, which brings us to the second point worth noting, and that is, for the majority of Singapore's population then, Singapore English and Singlish were one and the same. This is amplified by the use of a distinctly Singlish discourse particle lah, a feature one would not find in formal or standard use of English, both in Singapore and elsewhere. Lah here is an emphatic assertion (e.g. Kwan–Terry, 1978; Bell & Ser, Reference Bell and Ser1983; Lee, Reference Lee2022), drawing the readers to recognise that Singapore English is simply Singlish, but doing so in a friendly way, as lah is also a marker of ‘positive rapport between speakers, signalling solidarity, familiarity and informality’ (Richards & Tay, Reference Richards, Tay and Crewe1977: 146). Even though this was the first time the word Singlish appeared in print, the way Chandy had used it here suggested that this term would have been in circulation amongst the local population, and the synonymy between Singapore English and Singlish was perhaps also a well accepted norm. That Singapore English and Singlish were referring to the same thing can also be seen in a letter sent to the Straits Times in August 1979, a short excerpt of which is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Short excerpt of a letter published in the Straits Times on 23 August 1979

As the excerpt in Figure 6 illustrates, both the terms Singlish and Singapore English, seemingly already in circulation for years, were used to refer to the English spoken by Singaporeans. And this conflation of use peppered the numerous articles in the newspapers in the late 1970s and all through the 1980s. It is worth noting that thus far, as Singapore English and Singlish were gaining traction in their appearances in the newspapers, the term Singaporean English remained elusive.

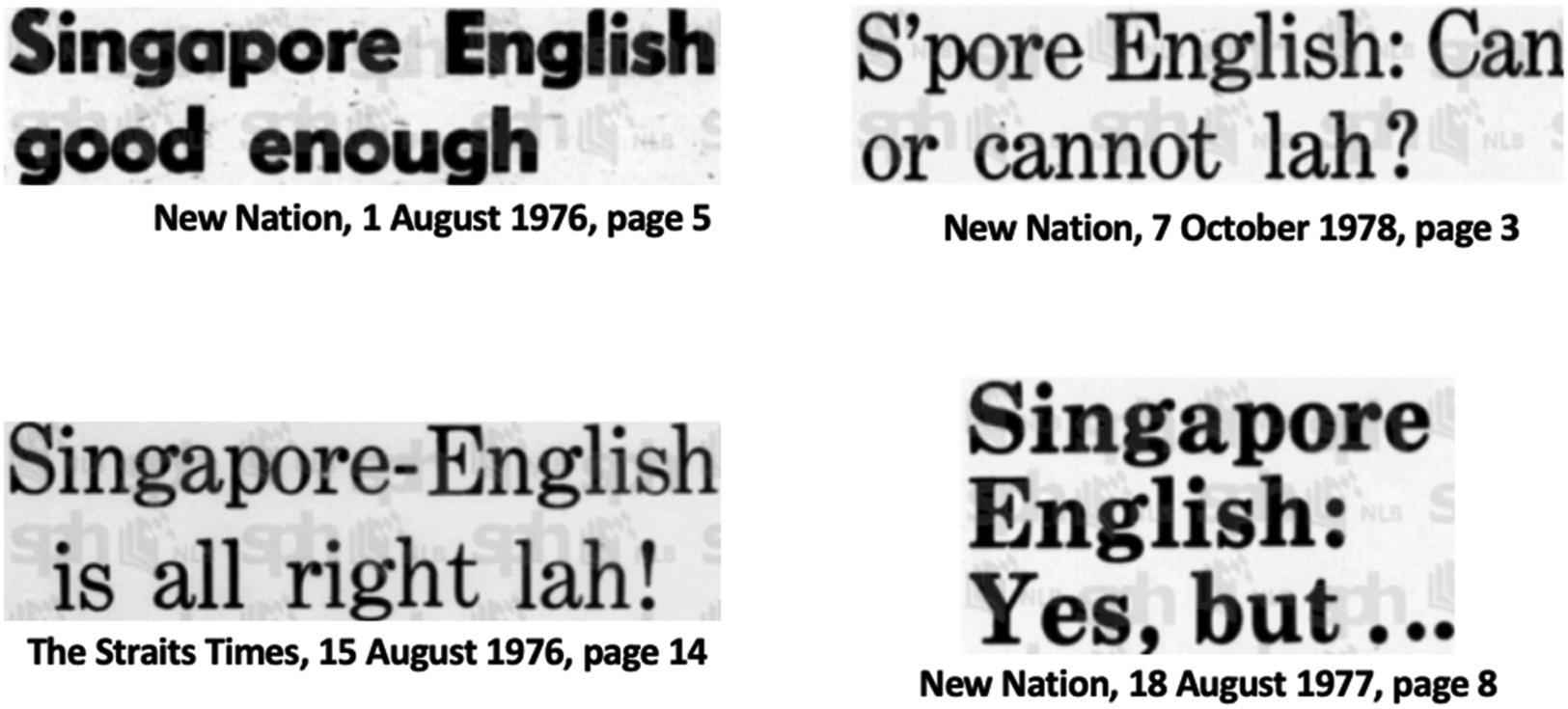

And there were many letters and articles in the newspapers reflecting similar sentiments to the one in Figure 6. However, it would not be an exaggeration to say that in the 1970s and 1980s, for every person who called for acceptance of the language, there were two others who disapproved of Singapore English/Singlish. Figure 7 shows some headlines of the debates on the topic in the late 1970s, illustrating the sentiments of the public on Singapore English.

Figure 7. Headlines in the newspapers in the late 1970s on Singapore English

This was a period of general disapproval toward the local variety of English in Singapore, which also fit neatly with what Schneider (Reference Schneider2007) would describe as the ‘complaint tradition’ typical of the nativisation phase in the evolutionary Dynamic Model. As Singapore English was developing and exhibiting linguistic innovations as a process of nativisation, these complaints focused on pointing out how these innovations were deviant or wrong as compared to Standard British English.

First wave (1975–1989): One Singapore English

The sense that Singapore English/Singlish was deviant was also driven in part by academics whose works were highly influential and shaped the way Singapore English was viewed. The first academic publicationFootnote 3 that drew attention to Singapore English was Crewe (Reference Crewe1977), an edited volume of ten essays devoted to describing the state of the English language in Singapore. Crewe, an Englishman, incidentally, joined the English Language and Literature department at the National University of Singapore as faculty member in 1975. All ten essays in the collection talked about Singapore English as a non-native variety of English, and the descriptions and discussions made no distinction between a standard or colloquial variety. If Crewe's volume marks the beginning of Singapore English research, then it is one that is very much in line with the way Singapore English was thought about publicly, starting from its first mention in 1907. There was only one type of English in Singapore, and that was Singapore English.

Coinciding with the first mention of Singlish in the newspapers in 1975, the first mention of the term Singlish in academic discourse also happened in 1975. Platt (Reference Platt1975) introduced the Lectal Continuum Model and named Singlish a ‘basilect’ and a ‘creoloid’. The Lectal Continuum Model, adapted from DeCamp's (Reference DeCamp and Hymes1971) idea of a speech continuum in pidgins and creoles, pegged Singlish as a ‘creoloid’ because unlike creoles, there were no circumstances under which Singlish had developed from a pidgin. The underlying belief here is that there is something abnormal or unnatural about the development of Singlish. Singlish, as a creoloid, according to Platt, has English as the lexifier providing the lexicon but has structural properties of other local ethnic languages, and ‘acquired by some children before they commence school and to become virtual “native” speech variety for some or all speakers’ (Platt, Reference Platt1978a: 55), and reinforced through the educational system. Singlish, ‘barely comprehensible to speakers of British, American and Australian English’, therefore cannot be of the same ilk as ‘native’ Englishes (Platt, Reference Platt1975: 363).

In this model, the Singapore English lectal continuum has a range of lects ranging from the acrolect through the mesolect to the basilect. The acrolect is the most prestigious, spoken by highly educated Singaporeans. Acrolectal Singapore English is very close to Standard British English in terms of its grammatical structure, though Platt (Reference Platt and Crewe1977b: 84) also notes that ‘a very distinct non-British English acrolect is gradually emerging’. In contrast, the basilect, which is also what Platt refers to as Singlish, is the furthest away from the British standard. It has low status, and is generally spoken by Singaporeans who are less educated and of lower social class (Platt, Reference Platt1975: 368–70). The mesolect then sits between the acrolect and basilect. The model is mostly concerned with speakers’ abilities to use a certain span of the continuum for functional and stylistic purposes. The number of lects made available to a speaker increases if the speaker is further up on the socio-economic scale as it is ‘the speaker's social status and educational background’ (Platt, Reference Platt1975: 368) that define his/her position on the social scale. This model therefore has also effectively segregated the speech community into three broad social classes: upper, middle, and lower. Figure 8 shows the Lectal Continuum Model and where Singlish sits on this continuum.

Figure 8. Platt's Lectal Continuum Model, adapted from Platt (Reference Platt1975: 369)

As can be seen in Figure 8, Speaker 1, the upper-class speaker, commands a range of lects spanning almost the complete continuum. Speaker 1 can speak Singlish as a form of colloquial speech, but it sits higher on the continuum as compared to Speaker 3's formal speech. Speaker 3, being low on the socioeconomic scale, is limited to a small span on the continuum, and remains stuck within the basilect such that this speaker's formal speech, which is still Singlish, is only slightly less basilectal than his/her colloquial one. In Platt's (Reference Platt1975, Reference Platt1977a, Reference Platt and Crewe1977b) description of Singlish, he has also made it clear that Singlish is a product of imperfect learning and spoken only by the uneducated and uncouth.

Even though Platt uses the term Singlish, his model drives home the point that Singapore English is one single entity, and one that has a continuum of which Singlish is part of. The lects are not linguistic varieties, but are markers of speakers’ status and social class. In this regard, all the speakers speak one English, and the differences in speech depend on the speakers who speak them. This way of thinking unfortunately remains highly influential, and has been the main argument used to eliminate Singlish in the state-run Speak Good English Movement (SGEM), launched in 2000 and running annually since.

Much has been written about the SGEM (see Rubdy, Reference Rubdy2001; Bruthiaux, Reference Bruthiaux, Lim, Pakir and Wee2010; Wee, Reference Wee2014). The fundamental claim of the SGEM is that Singlish is ‘broken, ungrammatical English, . . . [and] is English corrupted by Singaporeans’ (Goh, Reference Goh1999). This falls neatly in line with Platt's view on Singlish. And to underscore the belief that there exists only a singularity of Singapore English/Singlish, Goh Eck Kheng, Chairperson of the SGEM, in Reference Goh2010, summed it up: ‘We are only capable of speaking one way. And if we can only speak one way, we should ensure that the one way is what we call “Good English”.’ For the SGEM, if there was an English that was Singaporean, it was Singlish, and it was undesirable.

Second wave (1990–2019): Singapore English as a binary

Dissatisfied with the way Singapore English speakers have been treated in Platt's model, Gupta (Reference Gupta and Kwan–Terry1991) adopts the Diglossia model (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson1959) in the understanding of Singapore English. Focusing not on the speakers but on linguistic features, Gupta (Reference Gupta1989: 34) believes that there are ‘two grammatically distinct varieties of English in Singapore, both of which are used by proficient speakers of English’, and the speakers of Singapore English cannot be neatly classified along the lectal continuum as Platt would have them. The second wave of academic research on Singapore English can be said to have started with Gupta's localisation of the diglossia model, and thus begins a long-standing tradition of viewing Singapore English as a binary system. This way of thinking also set the stage for the next 30 years of descriptive work on Singapore English.

In the Singapore English diglossia model, there are two distinct varieties of English. The H (high) variety, acquired through formal education, ‘is the norm in formal circumstances, in education and in all writing’ (Gupta, Reference Gupta1994: 7), and is in complementary distribution with the everyday L (low) variety, which is the normal code for informal communication. In this regard, Standard English in Singapore is the H variety, and according to Gupta (Reference Gupta1994: 7), is similar to the Standard Englishes elsewhere. If the term Singlish was made visible in 1975, Gupta's diglossia model pushed it to the background. The term ‘Colloquial Singapore English’Footnote 4 is used refer to the L variety. Gupta deliberately avoids the term Singlish, as it is used to refer to the English of people with a poor proficiency in the language (Gupta, Reference Gupta1994: 5; alluding to Platt, Reference Platt1975, Reference Platt1977a, Reference Platt and Crewe1977b). In the diglossia model therefore, speakers use Standard Singapore English and Colloquial Singapore English in appropriate contexts and exploit them for functional purposes. This view is attractive because it treats the use of the two varieties of Singapore English as a matter of personal choice (Low & Brown, Reference Low and Brown2005), rather than as a function of a speaker's educational level (cf. Platt, Reference Platt1975).

It is therefore hardly surprising that research in the 1990s and 2000s saw a strong preference for the terms (Standard) Singapore English and Colloquial Singapore English. As mentioned at the beginning of this piece, I did a compilation of 500 published worksFootnote 5 on Englishes in Singapore ranging from the 1970s to 2021. Figure 9 shows the number of these works using the terms Singapore English, Standard Singapore English Footnote 6, Colloquial Singapore English Footnote 7, Singlish, and finally, Singaporean English.

Figure 9. Trends of published works using the terms Singapore English, Standard Singapore English, Colloquial Singapore English, Singlish, and Singaporean English, from 1975 to 2021 (n = 500)

As can be seen from Figure 9, published works using the term Singapore English take up the bulk of the 500 pieces surveyed. Of these, the ones published in the 1970s and 1980s use the term Singapore English as an umbrella term, making no clear distinction between the standard or colloquial varieties. This contrasts with more than 50% of the 200 pieces published in the 1990s and after, where authors use Singapore English to refer to the standard English spoken in Singapore. This also explains the sharp increase of the term Colloquial Singapore English in the 1990s and after. Where we only saw two articles using the term in the 1970s, and four pieces in the 1980s, the number quickly increased twofold in the 1990s, and then triple the number every decade. As mentioned in the footnote earlier, the two pieces in the 1970s are Platt (Reference Platt1975, Reference Platt and Crewe1977b), where Colloquial Singapore English is taken to be synonymous to Singlish, and similarly in the 1980s, in a co-authored piece (Platt & Ho, Reference Platt and Ho1982). The other authors who used the term Colloquial Singapore English were Foley (Reference Foley1988) and Gupta (Reference Gupta1989). The fact that the publications appeared at the end of the 1980s marked the shift toward the second wave, where Colloquial Singapore English is distinguished from the standard variety. As can be expected, with the increased usage of Colloquial Singapore English, some 60 authors in the last two decades have also been diligent in making sure that the variety they were studying was Standard Singapore English.

However, the 1990s was also a period of transition and confusion, and it can be seen in how researchers tried to wrestle free from Platt's Lectal Continuum Model while coming to terms with Gupta's Diglossia Model. Mohanan (Reference Mohanan1992), in common with many, steered clear of the usage of the acrolect, but nonetheless qualified the Singapore English he was studying as the ‘educated’ variety. Others, such as Pakir (Reference Pakir1993: 82), embraced the second wave enthusiastically, defining Singapore English as ‘a new non-native variety serving both High and Low functions in the society and as an agent for forging a new Singaporean identity’. Still others changed their minds as they rode the two waves of research. In an earlier work, Deterding and Hvitfeld (Reference Deterding and Hvitfeldt1994: 98) label Singapore English as ‘the mesolect, a variety halfway between the acrolect and the basilect’, but later in Deterding (Reference Deterding2003: 3), following the Diglossia Model, Singapore English is said to be the High variety. There were also those who seemed tired of taking a theoretical stand, and we can see Bao and Wee (Reference Bao and Wee1998: 40) describing Singapore English as ‘the variety of English one commonly hears in Singapore, from taxi drivers to university students’.

Despite the confusion in the transition between the two periods of Singapore English research, there is no doubt that the binary nature of (standard/colloquial) Singapore English in this second wave of research very quickly became the default mode of thinking. Colloquial Singapore English gained legitimacy as an object of enquiry, but ironically, Singlish took a hit, as if Colloquial Singapore English ‘is different from Singlish’ (Alsagoff, Reference Alsagoff2010b: 346) when, for all intents and purposes, Colloquial Singapore English is Singlish. While Singapore English research has moved in the positive direction envisaged in Gupta's Diglossia Model, the thinking about Singlish backtracked 20 years. The reason for this is, as mentioned earlier, Gupta's refusal to use this term in the Diglossia Model, rendering Singlish invisible. Yet Singlish was very much in the public consciousness, evidenced by what was discussed in earlier in newspaper appearances, and also in the SGEM. In most of the over 130 academic work which mentioned Singlish in the 1990s and beyond, the authors relied on the Lectal Continuum Model as a way of definition. The glaring absence of the term Singlish in the Diglossia Model left researchers in the second wave no recourse but to rely on Platt's definition of Singlish. Possibly also colored by the SGEM rhetoric, Kwan–Terry (2000: 85) refers to Singlish as ‘the uneducated variety of English in Singapore’, and in a similar fashion, Tan and Tan (Reference Tan and Tan2008: 469) define Singlish as ‘informal non-standard variety [and] the learner variety of English in Singapore’. Others outrightly invoke the Lectal Continuum Model. Rubdy et.al. (Reference Rubdy, McKay, Alsagoff and Bokhorst–Heng2008: 44) refer to Singlish as ‘the homegrown colloquial variant, . . . the basilectal variety with low linguistic capital’. Chew (Reference Chew and Vaish2010: 88), like Platt (Reference Platt1975), calls Singlish ‘the basilectal form of Singapore English’, and Lim (Reference Lim and Lefebvre2011: 271) ‘the mesolectal/basilectal variety of Singapore English’. Through the ways researchers have talked about Singlish, one can see how the Diglossia Model did Singlish no favors.

Returning to the -ean

The beating on Singlish is one of the reasons why we do not use the term Singaporean English. By way of conclusion, I return to the missing -ean to explain its absence. What does the suffix -ean do? The suffix -ean attaches to nouns to produce adjectives with two key meanings. In the first meaning, it connotes typicality. In this reading, Singaporean English is the English that is typical of Singaporeans. And it is this particular meaning that has dominated the thinking about Singaporean English. We see this in the earliest appearance of the term Singaporean English in Crewe (Reference Crewe1977). Interestingly, the term appeared only once, and while it may be completely accidental, the context of which it appears is revealing:

[W]hen we consider the use of formal English internationally, . . . Singapore does not yet conform strictly enough to this neutral standard – or perhaps fails to conform to it . . . Singaporean English has an important place in Singapore – particularly for national identity – but it must be kept separate from Standard English, which is neutral and international (Crewe, Reference Crewe1977: 106-107).

For Crewe, Singaporean English is deficient, and this same sense also comes across in four other publications that used the term Singaporean English. These four publications use the term to describe, as we know by now, Colloquial Singapore English or Singlish. In a couple of them (Ho, Reference Ho1998; Ziegeler, Reference Ziegeler2012), the term colloquial was attached to Singaporean English. This seems to suggest is that if there is something that is typically Singaporean about the English in Singapore, it is only the colloquial variety. It is clear then this is a problem created by the two waves of research over the last 45 years, and it boils down fundamentally to how Singlish has been treated. Therefore, if the logic follows, if Colloquial Singapore English or Singlish is what is Singaporean, and since it is believed to be deficient, Singaporean English is pejorative.

To move past this negativity, it is perhaps time, almost 50 years on, to forge into a third wave of research. One way to do so is to go beyond the binary of the standard and the colloquial, and to reclaim the right of Singlish to be treated as an independent entity (see Tan, Reference Tan2017). As we have seen throughout this paper and the history of the research, there is no real victory in insisting that Singlish is English or a kind of English. It is a well established fact that Singlish is a contact language that has input from many languages, English being one of them. I am in no way suggesting that Singlish is not influenced by English, because it is. However, calling it ‘Singlish’, and not ‘Colloquial Singapore English’ releases it from the crutches of the lectal continuum and diglossia models, and offers Singlish space to develop into its own being. If Singlish is not English, then there is nothing good or bad, standard or non-standard about it.

And this leaves us to handle Singapore English without the complication of Singlish. Can we now comfortably return the suffix to Singapore and make this English Singaporean? Besides the first meaning of typicality as mentioned earlier, there is yet another way to think about the suffix -ean. Another robust feature of this suffix is that it produces the meaning ‘belonging to’. In this reading, Singaporean English is then English belonging to Singapore. Again, Crewe's quote above also alludes to this, as he claims that ‘Singaporean English has an important place in Singapore – particularly for national identity’. Singaporean English therefore is the English that is Singaporean, and which belongs to a Singaporean. Unfortunately, Foo and Tan (Reference Foo and Tan2019) show that Singaporeans suffer from linguistic insecurity, and that may impede on their claim to linguistic ownership of English. This is not at all surprising, given the tumultuous relationship academics have had with Singapore(an) English and Singlish for the past 50 years, and the way Singaporeans have thought about these languages since Singapore English's first appearance in the press 115 years ago. But if we take a look at how English has developed in Singapore, there is cause to be hopeful. Schneider (Reference Schneider2007: 153–161) certainly exemplified it in his writing on the Dynamic Model and Singapore. It is remarkable to see Schneider using the term Singapore English until the final section describing the final developmental phases, and suddenly Singapore English becomes Singaporean English! It is almost as if Schneider has applied the evolutionary model beyond the development of the language to the nomenclatures. If so, the nomenclatures are no coincidences. We began with the noun-noun compound Singapore English when it was simply English in Singapore. And soon, we can attach the suffix -ean to Singapore, making it English belonging to Singapore. It is perhaps time, to use Schneider's words, for ‘the dissemination of the idea of Singaporean English being a respectable variety in its own right to the broader public’ (2007: 161).

Acknowledgement

This research is supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 1 (RG112/22).

YING–YING TAN is Associate Professor of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies at the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She is the first Singaporean to have received the prestigious Fung Global Fellowship from Princeton University. Besides writing on language planning and policy, she is also a sociophonetician who has published on accents, prosody and intelligibility, focusing primarily on languages in Singapore. Email: [email protected]

YING–YING TAN is Associate Professor of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies at the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She is the first Singaporean to have received the prestigious Fung Global Fellowship from Princeton University. Besides writing on language planning and policy, she is also a sociophonetician who has published on accents, prosody and intelligibility, focusing primarily on languages in Singapore. Email: [email protected]