Physicians are deeply invested in Canadian medicare because it is through medicare that they are paid. However, from the origins of state-administered medicare to the present, the majority of physicians have not been strong supporters. They opposed it frequently, fearing loss of income and individual autonomy. Some opponents are unaware that medicare was a boon to Canadian physician income, and many fail to connect their participation in medicare with responsibility for improving health outcomes through social determinants and equalizing access to care – although that was, and still is, its purpose. This paper will trace physician involvement – support and opposition – to medicare from its inception to the present, with special attention to small physician organizations that have supported medicare. It will close with an example of how physicians could display greater stewardship of social determinants. It will be shown that doctors supporting medicare were always in a small minority, usually young, idealistic and motivated by public-health concerns – and that, in response to various crises, successive groups of medical supporters of medicare rose up to replace their predecessors.

First, a caveat. This topic and its title were assigned. I added the negative in the title to allow for the possibility that physicians have not been stewards of medicare. According to the Oxford dictionary, stewardship is ‘the job of taking care of something’. Doctors who helped create and sustain medicare have been few in number; many more have been vocal opponents. Consequently, opposition might be seen as an aspect of stewardship, slowing, shaping and even strengthening medicare by highlighting its potential and perennial problems; a gardening metaphor springs to mind – between fertilizer and pruning shears.

Before MEDICARE: Canadian Association for Medical Students and Interns (CAMSI) and the Soviet example

Before medicare, ill health could ruin a family’s finances. In the interwar period, some doctors ran private insurance companies, including Associated Medical Services (AMS), which was founded 80 years ago in 1937 by Queen’s University medical graduate, pathologist Dr Jason A. Hannah. He understood how illness could devastate homes both emotionally and economically. Insurance offered security to people who could afford it, but the fees were often beyond reach for middle-class citizens and the poor. Other solutions to funding health care included the Saskatchewan Municipal Doctors scheme, which from 1916 had brought health care to remote, prairie towns, while guaranteeing decent incomes for medical participants (Lawson, Reference Lawson2005). Organized medicine was skeptical of the municipal doctor scheme, although it enjoyed attention and imitation from Alberta, Manitoba and the United States.

During the hostilities of World War II, groups of citizens and policy makers began to plan for post-war economic and social organization, seeking ways to avoid a collapse like the Depression of the early 1930s. Advisors to Ottawa on post-war reconstruction included Principals Robert Wallace of Queen’s University and Cyril James of McGill. Neither were physicians, but they were interested in equitable health care delivery and the programs used in Russia, an ally in the struggle against fascism. As part of Queen’s University Centennial celebrations in 1941, Wallace awarded honorary doctorates to James and to Dr Henry E. Sigerist. The erudite, Swiss-born Sigerist was a physician and professor of history at Baltimore’s prestigious Johns Hopkins University medical school. In his prominent book on Soviet medicine (Sigerist, Reference Sigerist1937), Sigerist had expressed the idea that medicine should develop along simultaneous, parallel lines of social and technological progress, with research in both. He warned that North American medicine was emphasizing technological over social progress. Some medical reviewers condemned Sigerist’s book as ‘propaganda’, deriding a historian for daring to comment on contemporary health care (C.B.F., 1938). However, others were taken with his Soviet example and the notion that medicine could concentrate on disease prevention (Davis, Reference Davis1938). On 30 January 1939, Sigerist graced the cover of Time magazine. For his socialist views, however, he would eventually be hounded out of the United States through the intimidation of the McCarthy era. Despite Sigerist’s fame, the Queen’s degree would be his only honorary doctorate (Duffin and Falk, Reference Duffin1996).

Dr Sigerist came to Canada again in 1943 and 1944, invited by small but active organizations interested in medicare: the CAMSI, the Health League of Canada and the Canadian–Soviet Friendship Society. Founded in 1938, CAMSI established international electives for medical students, worked to improve education, published a journal and organized an intern-matching program – precursor of today’s Canadian Resident Matching Service (Apramian, Reference Apramian2017). From 1942 to 1968, the CAMSI Journal published articles about social security, old age pensions, group practice, outmoded prisons and history. The editors invited distinguished medical professors from across North America to contribute: William Boyd, Harry Goldblatt, Wilder Penfield, Donald D. VanSlyke and Paul D. White. Henry Sigerist contributed papers on Soviet medicine and on the social history of medicine (Sigerist, Reference Sigerist1942, Reference Sigerist1943, Reference Sinclair1945). CAMSI Journal also featured an article by the newly elected Premier of Saskatchewan, Tommy C. Douglas (Reference Douglas1945) – something the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) never managed to do.

In 1943, Sigerist founded and edited the American Review of Soviet Medicine, the organ of the American-Soviet Medical Society; it would run for 5 years until the start of the Cold War. In November 1943, CAMSI invited him to address its annual meeting in Convocation Hall, University of Toronto. The University President H. J. Cody worried that the visit of a noted ‘red’ would stir controversy, but in the end, he decided to attend and host a dinner. Judging by the CAMSI Journal, the young doctors and medical students were intrigued by social medicine and open to the concept of medicare as a mechanism for health maintenance. They invited left-leaning J. Wendell Macleod to question “How Healthy is Canada?” (Reference MacDougall1942). As a student at McGill in the mid-1930s, he had imbibed Norman Bethune’s rhetoric about ‘socialized medicine’ with the ‘Montreal Group for the Security of People’s Health’ (Naylor, Reference Naylor1986; Horlick, Reference Horlick2007). Good health would flow from accessible systems of care and in consideration of what are now called the social determinants, such as employment; he laid out several proposals for achieving it. In 1952, Macleod became dean of the University of Saskatchewan’s new medical school.

After the war, CAMSI decided to merge with the Canadian Medical Association (CMA). Phagocytosed by a mature profession, CAMSI abandoned social activism, and its journal no longer printed articles about health care delivery or the former ally, now turned cold-war enemy. During the crisis of conflict, the idealism of youth had tilted in favor of medicare.

The Health League, led by the charismatic Gordon Bates, was created to combat venereal disease. Several scholars have recognized its influence (Cassel, Reference Cassel1987; Wilmshurst, Reference Wilmshurst2015; Carstairs et al., Reference Carstairs, Philpott and Wilmshurst2018). Having met Sigerist in Toronto in 1943, Bates arranged his return with an ambitious itinerary to Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal. Bates favoured any method of health care delivery that could advance his goals. Therefore, his support for medicare came from a conviction that it could be a vehicle for improving population health.

Taking advantage of the Health League invitation, the Canadian–Soviet Friendship Society also invited Sigerist to speak in Montreal in February 1944. Not a medical group, it nevertheless boasted prominent physician members, including neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield and patron Dr Charles Best (Anderson, Reference Anderson2008). Sigerist delivered lectures on ‘social medicine’ and health care in Russia. He also addressed members of Parliament on the Social Security Committee and met Tommy C. Douglas. No comment about the high-profile Health League tour appeared in the CMAJ, but it received wide newspaper coverage.

Before medicare, several medical groups – especially of young people and those involved in public health – flirted with the potential of medicare. Given what was to happen, it raises the possibility that medicare was more attractive when it remained an idea.

Early days of medicare: Hugh Maclean and Henry Sigerist in Saskatchewan

The history of medicare in Canada has been the subject of many scholarly articles, books and websites (e.g., Naylor, Reference Naylor1986, Reference Naylor1992; Taylor, Reference Taylor1987; MacDougall, Reference MacDougall, Pope, Tarasoff, Bliss and Decter2007; MacDougall et al., Reference Macleod2010; Marchildon, Reference Marchildon2012; Houston and Massie, Reference Houston and Massie2013; Bryant, Reference Bryant2016). Without rehearsing this well-known story in detail, I will briefly trace medical involvement in Saskatchewan, showing that most doctors were not stewards, unless its definition includes opposition. Among the many reasons why Saskatchewan became the ‘cradle’ of medicare, was its Municipal Doctor plan. Participating physicians had already accepted a kind of medicare with their salaries (Lawson, Reference Lawson2005; Houston and Massie, Reference Houston and Massie2013).

In 1944, when the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) party was campaigning to form the provincial government, the party leader, Tommy C. Douglas, needed physicians to help ‘sell’ the idea of medicare – not to citizens – but to the profession. The municipal doctors might be expected to support medicare, but some had been using that salary as a baseline, which they supplemented with private practice. They too worried about potential loss of income and autonomy. Douglas convinced surgeon Hugh Maclean to return from retirement to hit the campaign trail with a speech that described the health care plans, touted the value of medicare and provided medical endorsement to the platform. An odd figure in the Canadian left, Maclean had studied in Toronto, practiced in Regina and run for office on the CCF ticket several times, always unsuccessfully. Douglas reasoned that Maclean’s approval would help counter the many medical voices opposing medicare and raising doubts among citizens. When the CCF party won the election by a landslide, Douglas called Maclean the ‘godfather’ of his health care program and invited him to the investiture (Duffin, Reference Duffin1992).

Shortly after his victory, Douglas announced a survey of health needs in the province. By telegram, he invited Sigerist to lead it. Already well known in Canada, Sigerist would convey the authoritative approbation of a distinguished physician – outsider. The small team included a hospital superintendent, a nurse and two other physicians: Dr Mindel Sheps, a general practitioner and future biostatistician, and pediatrician Dr J. Lloyd Brown. The 3-week survey began 13 September 1944. On a cold, wet day in the middle of the tour, the team stopped in Saskatoon, where Sigerist addressed the provincial College of Physicians. His title – ‘Medicine for Today and Tomorrow’ – reflected his transformation from social historian, focused on the past, to technocrat confronting the future. He wrote in his diary that the doctors’ reaction was largely positive. The following day, Sigerist heard Douglas deliver a ‘brilliant speech’ to the same physicians. ‘They were afraid of him’, he wrote, ‘but he convinced them of his sincerity and made a very good impression’ (Duffin and Falk, Reference Duffin1996). Sigerist’s final report was submitted on 4 October – a short, pamphlet-like document, making recommendations that bore an uncanny resemblance to the campaign speech of Dr Hugh Maclean. A copy of Maclean’s speech is with Sigerist’s papers in the Johns Hopkins University archives.

Hospital coverage was enacted immediately, but Douglas was wary of the physicians and understood that they could sway public opinion. He proceeded slowly. On an ‘amicable’ agreement with the profession, social assistance was provided for the elderly, disabled and poor – especially widows. A pilot project was established in the town of Swift Current, based on earlier municipal doctors plans, with local citizens approving an extra tax to cover doctor bills (Houston and Massie, Reference Houston and Massie2013). Recently at its 70th anniversary, the board of ‘Health Region #1’ was praised for its contribution; its 12 members are called the ‘Fathers of Medicare’. None of these people were doctors, nor were they women (Donnelly, Reference Donnelly2016). A few physicians collaborated with the plan; some came from the United States out of political sympathy for the endeavor.

With Douglas as leader, the CCF won the next four elections with majorities. It was not until his final term as premier, and after he had left for Ottawa to head the newly formed federal New Democratic Party, that the long-planned medicare bill became law. Nearly two decades had passed since Douglas had been elected on that promise. One major concession was that physicians were to be paid by fee-for-service, not salary – a concession that reassured the doctors, but ever after added to the complexity and costs of running the programs. Nevertheless, doctors opposed the new legislation and launched a bitter strike that lasted for 3 weeks in June 1962 (Tollefson, Reference Tollefson1964; Badgley and Wolfe, Reference Badgley and Wolfe1967). In support, doctors’ wives and many citizens formed Keep Our Doctors Committees – like the coffee klatches that had been used by the American Medical Association to oppose various health care bills in that country (Mohamed, Reference Mohamed1963; Skidmore, Reference Skidmore1989, Reference Skidmore1999). In the end, an agreement was reached and the doctors returned to work; amendments allowed extra billing and opting out – concessions that became difficult to relinquish (Marchildon, Reference Marchildon2016).

Organized medicine – represented by the CMA Public-Relations committee – watched the strike with some alarm. The CMAJ referred to it as the ‘Saskatchewan affair’ and reported both negatively and positively on its outcomes and the opinions of physicians. So in these early days, as medicare was established in Saskatchewan, the vast majority of doctors were not stewards of medicare: they were neutral, skeptical or opposed. Whatever their views, however, doctors elsewhere saw the Saskatchewan Affair as a harbinger of things to come.

Medicare goes national: where are the medical stewards?

In 1961, a year before the Saskatchewan strike, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker invited his Saskatchewan law-school classmate, Justice Emmett M. Hall, to chair another survey – this time national: the Royal Commission on Health Care Services. To ensure doctors’ earnings would not be diminished, Hall gathered information about physician income through Taxation Statistics (Canada, 1948–1995) from as far back as 1957 and had it printed in yellow, softcover books. The income of Saskatchewan doctors rose sharply in the year following the 1962 strike (Canada, 1963–1972). Doctors were making more money than in the past, partly because all their bills were paid. By 1965, 73% of the province’s doctors declared medicare a success (Thompson, Reference Thompson1965). Nevertheless, doctors elsewhere remained skeptical and mocked these reports in prestigious medical venues such as the CMAJ. Hall’s commission met with more than 400 groups, at least three dozen of which represented physicians: professional associations, provincial licensing bodies and specialist groups, including CAMSI and the Health League. He also heard from insurance companies, including AMS (Hall, Reference Hall1964: v. 1: 890–903). Hall made 256 recommendations for medicare in Canada, but he made it clear that its basic principles should go well beyond payment of hospital and physician services; he expected a second stage in which the entire population, as individuals and collectively, would bear responsibility for participating in health maintenance for both economic and humanitarian reasons (Hall, Reference Hall1964: v. 1: 3–10).

Another two-decade gap emerged between Hall’s report of 1964 and the Canada Health Act of 1984, mostly because of physician opposition. The initial 1966 Medical Care Act promised cost sharing at about 50–50 between the federal and provincial governments. It identified five pillars or principles to be upheld: universality, comprehensiveness, accessibility, portability and public administration. Some doctors were initially supportive of the concept – especially those working in underserviced areas and public health. Medicare slowly began to be implemented in different parts of the country province by province. However, the large professional associations were skeptical. In the 1970s, the unfettered costs of the program began to spiral upwards and the federal government started introducing measures to control them (Hatcher, Reference Hatcher1981). Amendments to the act in 1977 essentially decoupled federal transfers from the need to respect the spirit of the legislation. Medical resistance arose from the perceived ‘strangulation’ and ‘restrictions’ of services owing to reduced federal transfers and tightened controls. By the late 1970s, many doctors were opting out, including half the doctors of Prince Edward Island (Geekie, Reference Geekie1979). Some were extra billing or charging user fees; many were leaving for the United States. My large Toronto medical class of 1974 saw one-third of its members move south. The chaos and fiscal problems meant that the values of medicare were slipping away.

The concerns resulted in ‘SOS Medicare’, an emergency conference held in Ottawa in 1979 and sponsored by the Canadian Labor Congress. Addressing the opening, Tommy Douglas claimed that eliminating the fee barrier between doctor and patient had been the ‘easy’ part; the next steps were essential, but more difficult: cost reduction, through programs such as group practice or capitation; and disease prevention, through improved standards of living – soon to be called, the ‘social determinants of health’ – echoes of Macleod and Sigerist (Douglas, Reference Douglas1979; MacDougall, Reference MacDougall, Pope, Tarasoff, Bliss and Decter2007). This agenda has often been called the unfulfilled ‘second stage’ of medicare (Rachlis, Reference Rachlis2007). The anxiety of the late 1970s led to another invitation to Justice Emmett Hall to review medicare. His 1980 report laid the groundwork for the Canada Health Act of 1984, endorsing the five pillars established 20 years earlier. Absent the doctor salaries that he had long advocated, Hall supported the notion of binding arbitration for determining physician fees.

In the 1979 turmoil, a grassroots citizen organization – the Canadian Health Coalition (CHC) – was created to support medicare; provincial equivalents soon arose. The first chair of the CHC was Jim Macdonald of the Canadian Labor Congress.Footnote 1 The CHC now claims to represent more than 600,000 Canadians. The current president is a nurse from Alberta and two physicians serve on its 13-member board: Michelle Brill-Edwards and Joel Lexchin. However, CHC’s constituent societies are not medical, rather they are gatherings of seniors, parents, church groups, unionized workers, environmentalists, and members of civil-society movements and the political left.

The Medical Reform Group (MRG)

Around this same time, a smaller group also appeared: the MRG. Its founders, Fred Freedman and Gordon Guyatt, both resident physicians, experienced a meeting of minds in the Toronto Western Hospital cafeteria in 1978 (Dale, Reference Dale1983; Guyatt, Reference Guyatt, Oxman and Woodside1995). Excited by finding kindred, political spirits in each other, they held informal discussions and spread the news by word-of-mouth. A letter to 5000 doctors and an advertisement in CMAJ drew a few more sympathizers. A meeting was held at Hart House in May 1979, and various working groups were created. Dr Philip Berger, a young family doctor from Winnipeg, practicing in Toronto’s Riverdale neighborhood, joined the working group to draft the Constitution with Dr John Marshall. By 1 November 1979, they announced their existence to the world, calling themselves the MRG. Beyond describing MRG’s support for medicare, the front-page report in the Toronto Star emphasized its unprecedented ‘break’ with the Ontario Medical Association (OMA) (Landsberg, Reference Landsberg1979).

Some members hesitated to openly identify as MRG members for fear of career repercussions. The first to do so were family physicians Debby Copes and Cynthia Carver. Philip Berger remembers his ‘coming-out moment’ – a necessary crossing of the threshold – when he agreed to debate extra billing on Canadian Broadcasting Company radio with Edward Moran, executive director of the OMA. Reprisals were few, but real. Occasional specialists refused to see Berger’s patients in consultation. Guyatt, who served on the MRG steering committee throughout its existence, knows that his bid for a McMaster University administrative position was blocked by a prominent OMA member who told the search committee that his appointment would ‘send the wrong message’ about the school. He also recalls a medical chief upbraiding him for having stood in front of a recognizable façade to deliver an anti-OMA message on local television. Another superior never forgave Guyatt for referring to some colleagues as ‘greedy’ on the front page of a major daily (Desmond, Reference Desmond1991). These incidents were annoying, but minor; for the most part, MRG members were left alone. OMA officials viewed them with head-shaking bemusement as an innocuous fringe.

MRG reflected the two themes described above: youthful idealism and the conviction that medicare was a better system, not only for removing financial barriers to medical services, but also for maintaining and improving national health – medicare’s ‘second stage’. MRG declared that health care was a right, that it was political and social, and that institutions needed to change to sustain the work force and recognize valuable contributors equally (McDermid, Reference McDermid1987). In other words, MRG did not place doctors at the top of a hierarchy. Furthermore, it conceived of medicine as something much bigger than doctor-work, and made social conditions part of its mandate. Dr Joel Lexchin recalls how good it was to be with people who thought the same way. It was also fun, attending debates in the Ontario Legislature or conferences on social issues; Lexchin met his physician spouse through MRG. For the next three decades, MRG was often the only medical voice for medicare and against organized medicine.

MRG members spoke out against privatization, doctor strikes and physician-sources of inefficiencies. Recognizing the need for change, they supported research into ways to improve health care delivery – the research that Sigerist had called ‘social progress’. They defended medicare when Canadian colleagues challenged it in such prestigious venues as the New England Journal of Medicine (Guyatt et al., Reference Guyatt1990; Linton, Reference Linton1990). These stewards of medicare were always few in number, apparently never more than 200. (I have not been able to identify the actual numbers of MRG physicians through time – a good project for a graduate student.) Always constituting a minority of Canadian physicians and concentrated in Ontario, MRG’s activity and prominence rose and fell with each medicare crisis, especially whenever talk of privatization or extra billing returned.

Strikes and lawsuits: oppositional stewardship

Many members of the profession see stewardship of medicare as seeking to ensure that physicians are better remunerated. Doctor strikes and threatened strikes are a feature of third-party payment, although they have tended to backfire on the profession, even when financial concessions are achieved. Strikes took place or were threatened in almost every province since 1984 (see Table 1). Ontario doctors staged a 1-day walk-out in June 1982, and in 1986, they went on strike for 25 days – the longest medical job action in Canadian history. Once again, the issues were money and autonomy. In accordance with the Canada Health Act and to obtain federal transfer payments, the province had to ban the practice of full billing, which was used by only 12% of doctors. Nevertheless 50–60% of doctors supported the strike, canceling surgeries and closing offices and hospital emergency rooms. Before and during the strike, the MRG received prominent media attention, disproportionate to its numbers. OMA officials complained about the undue attention given to MRG, partly because reporters sought dissenting views (Goodman, Reference Goodman1986). The striking doctors had little public support and lost credibility as a caring profession (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson1986; Sinclair, Reference Skelly1986; Meslin, Reference Meslin1987). Their characteristics, such as relative wealth and right-leaning politics, became objects of study as ‘risk factors’ for predicting future behavior of other doctors in similar situations (Kravitz et al., Reference Kravitz, Shapiro, Linn and Froelicher1989).

Table 1 Some doctors strikes in Canada

Hoping to restore public confidence, AMS president Dr Donald R. Wilson launched an inquiry to learn what citizens wanted from their doctors – a program that became Educating Future Physicians for Ontario (EFPO) (Neufeld et al., Reference Neufeld, Maudsley, Pickering, Walters, Turnbull, Spasoff, Hollomby and LaVigne1993; Maudsley et al., Reference Maudsley, Wilson, Neufeld, Hennen, DeVillaer, Wakefield, MacFadyen, Turnbull, Weston, Brown, Frank and Richardson2000; Seidelman, Reference Seidelman2017). This project inspired the later development of the seven CanMEDs competencies, which include Advocacy, Collaboration and Communication (Frank and Danoff, Reference Frank and Danoff2007; Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Austin and Hodges2011). Wilson aimed to guide future physicians to better stewardship by reminding them of the obligation to serve the public according to its self-defined needs.

Ever since medicare was born, pundits have predicted its demise in medical metaphor. Titles in the CMAJ from the 1970s forward include the words, such as ‘strangling’ ‘financially sick’, ‘falling apart’, ‘prognosis guarded’ and ‘dying’; they describe its rescue as ‘saving’, ‘renewing’ or ‘tuning up’ medicare in the face of ‘an accelerated war’ waged by the profession. Yet, the immense popularity of the program could not be denied. Through the 1990s, following deep cuts imposed to balance the federal budget, more talk emerged of unsustainability, user fees and extra billing. Strikes took place in British Columbia, Manitoba and New Brunswick. Again, MRG members were active, making press releases and defending public payment over medical selfishness (Carver, Reference Carver1996). CMAJ acknowledged that ‘not all doctors’ support job action, citing MRG, which, it stated, ‘would like to become a national organization’, but had ‘been unable to attract required critical mass of members’ (Anon, 1998).

In 2002, former Saskatchewan premier Roy Romanow led yet another commission to survey the problems. National, provincial and territorial medical associations made submissions, as did members of the MRG. His report constituted a resounding endorsement for the original ‘values’ of medicare (Romanow, Reference Romanow2002). Soon after, a new Health Accord restored transfer funding to the provinces for a decade, during which time the strikes and threatened strikes subsided (Health Canada, 2004).

Beyond criticisms and strikes, doctors have used the courts to attack medicare. The famous Jacques Chaoulli – George Zeliotis case resulted in the 2005 Supreme Court decision that forcing patients to wait for orthopedic surgery violated the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In other words, buyouts and private insurance should be permitted, not banned. Many observers in Canada and the United States predicted that the judges’ decision would bring about the end of medicare (Anon., 2005; Krauss, Reference Krauss2005; McKenna, Reference McKenna2005). Medicare opponents moved quickly to take advantage of the ruling, while supporters rushed to contain it (Flood et al., Reference Flood, Roach and Sossens2005). Again the MRG spoke up. In August 2005, its student section (founded in 2003) petitioned the CMA with 1134 signatures – representing 20% of the country’s future physicians. They decried CMA’s apparent comfort with the idea of privatized health care. The Canadian Association for Interns and Residents also voiced its opposition to privatization in August 2006. Nevertheless, the CMA voted to endorse the idea of more privatization, allowing two-tier health care (Sibbald, Reference Sibbald2006a, Reference Sibbald2006b).

Idealistic youth were defending medicare once again, and once again, they did so in opposition – not to the government, not to citizen demands – but to organized medicine itself. It would be British Columbia’s turn to generate the next President of the CMA – and in keeping with the newfound acceptability of privatization, the provincial medical association elected Dr Brian Day, who defeated Dr Jack Burak and four others. At the CMA convention itself in the summer of 2006, Burak again challenged Day from the floor. This act was unprecedented, because candidates are usually acclaimed; however, Day won again. A British immigrant and self-avowed refugee from the National Health Services, Day operated private surgical clinics in flagrant violation of the Canada Health Act. In 2002, Day’s brief to Romanow made 10 recommendations, including ones to repeal the Canada Health Act, increase business practices, allow privatization, reduce bureaucracy and union influence, and introduce user fees.Footnote 2 As in-coming CMA President for 2007, he said that he did ‘not believe in privatizing medicare’ (Fayerman, Reference Fayerman2006; Gratzer, Reference Gratzer2006; Sibbald Reference Sigerist2006c). However, Dr Day’s position was clear: he would not privatize medicare, he would scrap it altogether. He later achieved notoriety in advertising for the Republicans against Obamacare (Ward, Reference Ward2009; Clemens and Barrua, Reference Clemens and Barrua2014). At the time of writing, his ‘Cambie case’ against the British Columbia government is before the provincial Supreme Court (defendants are the Attorney General, the Minister of Health and the Medical Services Commission) (Picard, Reference Picard2016b).

Passing the torch: Canadian Doctors for Medicare (CDM)

Wide-coverage of Day’s emerging designation as B.C.’s choice for future CMA president began circulating in February 2006, even reaching the same New York Times reporter who had analyzed the Chaoulli decision as the end of medicare (Krauss, Reference Krauss2006). The Chaoulli case and the anticipated election of Day sparked the formation of another group of idealistic, young doctors in May 2006: CDM. Although MRG had claimed nation-wide membership, CDM used its greater funding to extend its mission well beyond Ontario inner cities, making strategic use of the internet and social media to advance its agenda. By September 2006, it claimed one thousand members (Sibbald, Reference Sibbald2006b). Its leaders have always emphasized the importance of evidence-based decision making – a globally important concept elaborated by MRG founder Gordon Guyatt, who joined CDM (Skelly, Reference Skelly2010; Sur and Dahm, Reference Sur and Dahm2011; WLH, 2016).

The first director of CDM was family physician Dr Danielle Martin. Although CDM membership is open to anyone, its original 17-member board was made up entirely of physicians, among them two former deans, the former head of Doctors Without Borders, and representatives from across the country, including the territories. At the CMA meeting in 2007, when Brian Day officially became president, CDM hosted a popular showing of Michael Moore’s controversial film Sicko. CDM and its sister group, Medecins québécois pour le Regime Publique (MQRP) founded in 2008, have collaborated on a number of initiatives, held joint conferences, and issued position statements and press releases, referring wherever possible to evidence-based research. The MQRP’s ‘Montreal Declaration’ was an indictment of the attempt to heal the health care system through increased privatization, characterizing it as ‘erroneous diagnosis’ and ‘harmful treatment’ (MQRP, 2008). CDM chair Danielle Martin was a signatory.

From its inception, CDM began its successful lobbying for the future CMA presidency of Ottawa’s Jeffrey Turnbull, a supporter of medicare. In 2009 when it was Ontario’s turn to generate a president, Turnbull was elected to step up in 2010 – a sea-change in attitude that led MRG, CDM and MQRP to breath a temporary sigh of relief.

Dr Martin became a media darling not only in Canada, where she regularly chats about health matters with television anchors on national networks, but also in the United States. In March 2014, her answers before a US Senate committee, including Senator Bernie Sanders, went viral obtaining almost 1.5 million hits on youtube (Sanders, Reference Sanders2014). Her recent book Better Now, containing ideas for improving medicare from within has been endorsed by Sanders, as well as Roy Romanow, former Senator Hugh Segal and Naomi Klein (Martin, Reference Martin2017). CDM’s next chair was public-health doctor Monika Dutt, from Nova Scotia who was replaced in late 2017 by MRG stalwart Joel Lexchin. Its board is still comprised of physicians, with the exception of one medical student, although what proportion of members are clinicians has never been clear. Like MRG, CDM constitutes a small minority of the nation’s doctors.

For 8 years, MRG continued in parallel with this new national entity. Why was CDM needed when MRG already existed? Why did the younger doctors not merge with the long-standing group, infusing it with new energy and new funds? Was it necessary for youth to distance themselves from the crusty, confrontational elders barnacled with enemies? Did they perceive advantages in proclaiming its national base, in contrast to MRG’s conspicuous Ontario roots? Did they wish to narrow the focus to medicare alone, avoiding the social activism of the older group? MRG had been intimately associated with the issue of extra billing, but it also made pronouncements on many other health and social issues. Once extra billing was defeated, media outlets considered MRG’s goals had been attained and ignored its statements on other matters. Internal conflict over how far MRG should go in its activism beyond conceptual and geographical borders of Canadian health care provision also resulted in attrition. Similarly, some members found resistance, even among the progressive doctors, to recognizing iatrogenic causes of waste, fearing that speaking out about ‘inefficiencies’ would invite cutbacks rather than structural solutions. Numbers declined both actively and passively. Moreover, the aging MRG activists had not replaced themselves or their leaders, and they were immersed in busy careers with their own pet issues; they had had a good run. The steering committee reasoned that the two groups were duplicating agendas and making confusing, double demands on the small community likely to support them both. MRG decided to pass the torch, sent its papers to the Ontario Archives, and officially ceased operations in late 2014 (Godkin, Reference Godkin2014). MRG founders still articulate their views with vigor; many joined CDM.

It was in 2009 that Irfan Dhalla, a founding board member of CDM, whom I had known since his student days, contacted me by e-mail to ask if I knew anything about the history of doctor income and its relationship to medicare (Dhalla, Reference Dhalla2009). He recalled that I had conducted a history of medical tuition fees – showing how the unprecedented hike following the 1995 election of the Mike Harris government had unraveled more than a century of improved access to education. CMAJ had published it as a cover story back in 2001 (Duffin, Reference Duffin2001). Dhalla wondered if anyone had done something similar for medical income – and if not, could I do it. I checked the literature and consulted with my health economist buddies. The answer was ‘no,’ it had not been done. Scattered articles explored the income of individual doctors in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but to find a reliable source of physician income over the last 75 years would require serious digging.

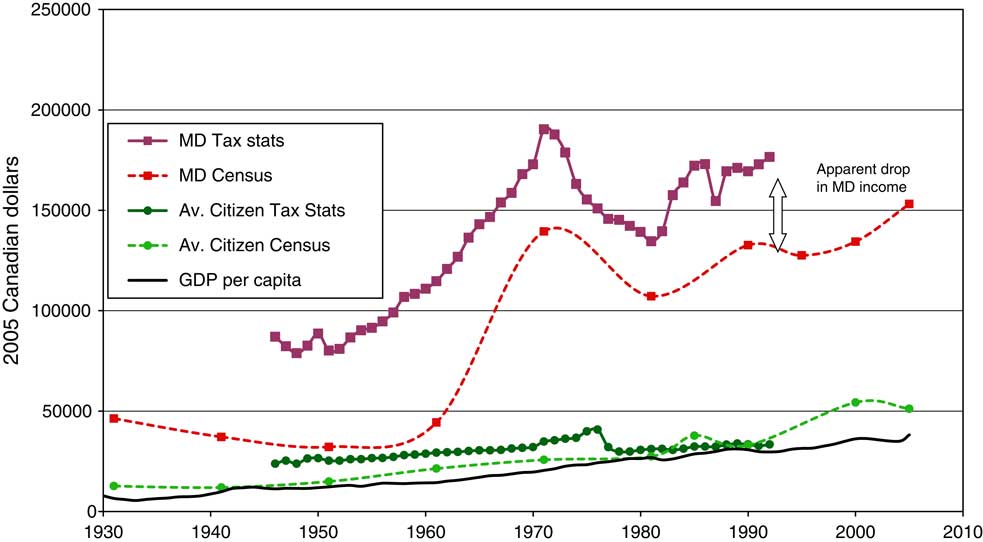

Doctors do not reveal their incomes. Their names do not appear on the various provincial ‘Sunshine Lists’ that supposedly reveal the taxable income of all people who are paid more than $100,000 annually from the public purse (Picard, Reference Picard2016a). Yet, the vast majority of doctors fall into that category. For those in Ontario whose names and incomes do appear on those lists, the secrecy of physician income is a continuing source of annoyance and much speculation, skewed by a focus on the highest earners (Fayerman, Reference Fayerman2016; Picard, Reference Picard2016b). The Blue Book website of British Columbia reveals total billings, but billings include expenses (Picard, Reference Picard2016a). Three sources, however, could serve the research: the medical income studies done for the Hall Commission in the 1960s; Taxation Statistics of the Receiver General published every year on the basis of T4 slips; and the Census of Canada (Earnings; Taxation; Census). Unfortunately, Taxation Statistics ‘worked’ only until 1992; after that year, citizens were no long obliged to state their occupations, although the report was still published. I also learned that everyone – doctors, plumbers and housewives – tend to relate lower incomes to the census-takers than they declare on their income tax forms. It took months, but eventually I was able to generate a chart with four lines in equal dollars– two lines for the average Canadian doctor and two for the average citizen – one line representing Taxation Statistics (up to 1992) and the other, Census data (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Net income of Canadian physicians and average citizens with gross domestic product (GDP). Source: Census of Canada and Taxation Statistics. Note: Conversion to 2005 dollars through historical Consumer Price Index at Statistics Canada.

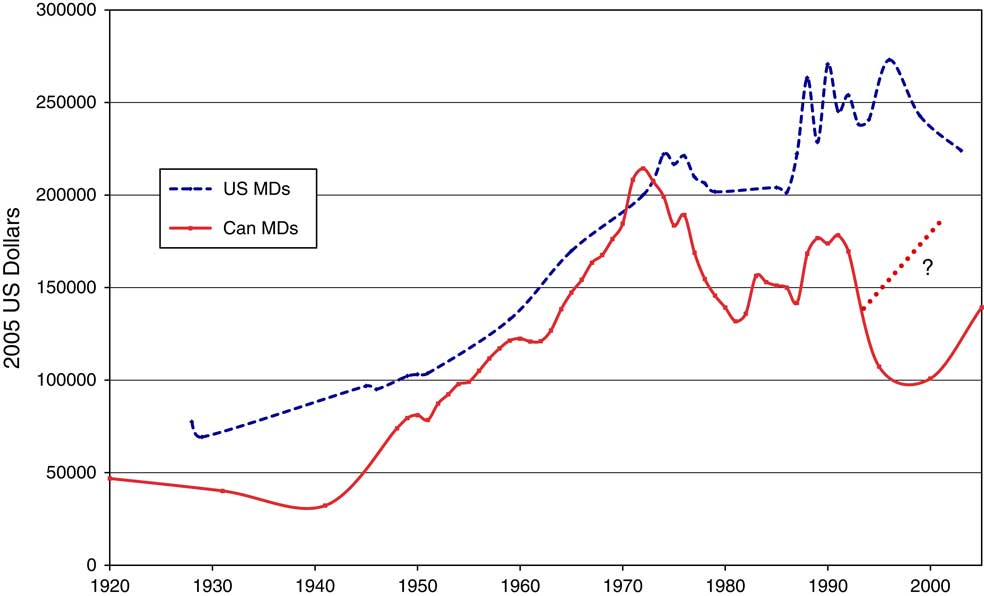

The result was impressive and surprising. Medicare was enacted across Canada over a 25-year period – essentially between the doctors’ strikes in Saskatchewan and in Ontario. During that period, Canadian medical income rose dramatically when compared with that of the average citizen. Even relying on the lower figures in the Census data, it became clear that doctors were earning several times the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Responding to the perennial question, I tried to compare Canadian physician income with that in the United States, relying on occasional publications and friends who sent data from surveys of the American Medical Association. Canadian doctor income sometimes exceeded that of their American counterparts – especially in the 1970s, that period of chaos and anxiety when so many of my classmates headed south. For the Canadian line, I averaged data from Taxation Statistics and the Census – which produced an apparent, but factitious, drop in the 1990s, owing to the absence of taxation information beyond that date. The dotted line and ? represented a projection of the trend in Canadian physician income from the Taxation Statistics source unavailable after 1992 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Physician income in Canada and the United States, 1920–2005. Source: For Canadian physician income, see Census of Canada (1931–2006) and Taxation Statistics (1948–1995) (references 24 and 28); US physician income (see references 48–54). Note: ?=Extrapolation of Canadian physician income based on Taxation Statistics.

Do the doctors who complain about money and freedom know that medicare significantly augmented their income? Excited by these findings, I bundled up the work and sent it to the CMAJ, which had published the similar, bean-counting research into tuition fees. Rejection was swift, the second fastest that I have ever received – and it came without peer review. The editors referred to my own observation that more reliable data were unavailable.Footnote 3 Whose fault is that, I thought? Although doctors are paid from the public purse, they do not have their T4 incomes published on the ‘Sunshine Lists’. Next, I sent the paper to the Canadian Journal of Public Health, which rejected it even more quickly – on the same day – my fastest rejection ever, and also without peer-reviewed, claiming that the topic of physician income was ‘unsuitable’ and fell outside its purview.Footnote 4

Depressed at having done all this work only to encounter a lack of interest in the results among physician gatekeepers, I read the paper at a history meeting held at the Mayo Clinic in 2010. An editor of the American Journal of Public Health, who happened to be in the audience, invited a submission. Not only was the article accepted, the editors, and readers asked for an expanded introduction to provide a ‘primer’ on the history of medicare in Canada.Footnote 5 As plans for Obamacare were evolving, these readers thought that the article could explode some myths and reassure medical professionals who feared losing money and autonomy – the same self-interests that drive organized medicine in Canada. Consequently, thanks to medical history, I got a publication in an American journal with a higher impact factor than its Canadian equivalent (Duffin, Reference Duffin and Falk2011). The topic was not outside its purview and the evidence was deemed good enough – after all, it was the best evidence available because the profession prevents us from knowing more. The main takeaway point was that physician income in Canada is already high and this evidence-based research demonstrates that medicare helped. Far from exploding myths, however, the article has been cited only five times. The durable American misconceptions about the misery of Canadian patients and practitioners fit in the realm of ‘convenient truths’ and ‘alternative facts’.

Ontario doctors seem not to know about medicare’s impact on their earnings. For several years, the OMA has run a magnificent, award-winning, public-relations campaign, ‘Your Life is Our Life’s Work’. Whenever fees were to be negotiated, gorgeous photos of doctors with happy, healthy, satisfied patients were trotted out in newspapers, on television, in the subways and bus shelters. The message was that people should love their own doctor and recognize that she deserves more money – because health is precious and doctors are the sole providers, even the sole stewards.

More recently the issue has turned ugly. Dissatisfied with the OMA, the government, and the outcome of the 2016 negotiations, medicare-deniers have invested time, energy and money in creating groups to demonize Premier Kathleen Wynne, her ministers, and the OMA leadership. Such groups include the Coalition of Ontario Doctors, Concerned Ontario Doctors, Doctors for Justice, Doctors Ontario – counter groups to the ones I have described thus far. Their disturbing rhetoric provokes public revulsion reminiscent of 1986. One columnist stated that ‘doctors don’t get it’ – ‘medicine is a team game’ (Yakabuski, Reference Yakabuski2016). Others have pointed out, repeatedly and for decades, that more money is not a solution when Canada already spends the second highest proportion of GDP on health care for one of the poorest outcomes in the developed world (Coyne, Reference Coyne1996, Reference Coyne2016). They identify the medical profession as an obstacle to change. Nevertheless, doctors link the issue of their remuneration to patient care, claiming that the government ‘forces’ them to ration visits, and they terrorize the population with veiled threats of job action – as implied at the website Concerned Ontario Doctors (2016). A sordid Amy Winehouse parody, produced by a family physician, garnered over 3000 views; one commentator suggested that the video be sent to ‘all the students and residents duped into voting yes’ (Mags the Singer, 2016). Indeed, the Canadian Federation of Medical Students had weighed in with a position paper supporting medicare and rejecting privatization (Sumalinog et al., Reference Sumalinog, Abraham and Yu2015). Clearly the dissenters perceive another enemy in youthful idealism – the young doctors who have the gall and naïveté to believe that they are in the profession to keep people healthy and can use medicare to do it.

When physicians complain about their income – as Ontario doctors have been doing, I am embarrassed. When they pretend that their complaints are about patient health, I cringe at the hypocrisy. And in both situations, I am struck by their betrayal of the much-vaunted competencies that they were supposed to have embraced following the painful strike of 30 years ago: Advocacy, Communication and Collaboration. Granted, great discrepancies exist between the highest and lowest paid doctors. To solve that inequity, however, doctors should not be attacking governments – which represent the people who are their patients; they should be communicating and collaborating with each other to redistribute the wealth and rationalize their fees. They do not.

What’s more, physician educators have recently twisted one of those competencies from Manager, which implies stewardship, to Leader. Long ago when EFPO first appeared and leadership fellowships were offered, I began to wonder why we do not encourage fellowships in medical ‘followship’. The kinds of egos and intellects that enter medical schools need far more educating in that direction than in any other. Certain cherished postures of medical care encourage it. For example, insistence on the primacy of the doctor–patient relationship implies ethical value in a stance for the individual and against collectives. Organized medicine consistently strives to make the medicare agenda as being about physicians, as leaders and gatekeepers, their incomes and freedoms; even clinicians who sympathize with ‘saving’ rather than killing medicare argue that doctors should lead (Pinney, Reference Pinney2016: 217). By insisting on leading, physicians see themselves as more important than other components of the system. In February 2017, when a MRG charter member Philip Berger eloquently expressed doubt about medical dominance, he became the victim of cyber-bullying by colleagues (Berger, Reference Berger2017; Star Editorial Board, 2017). Medical students who agree with him have been threatened with career consequences, while the recently deposed OMA President, Dr Virginia Whalley, received hate messages expressed in unspeakably sexist language, from an Ontario anesthesiologist (Boyle, Reference Boyle2017). However open we may be to the notion of opposition as construction, this is not stewardship, it is shameful.

The next group is born

And yet – since 14 September 2016 more than 400 Ontario health care practitioners have signed an open letter calling itself ‘the way forward’ (Anon., 2016; Boyle, Reference Boyle2016). Disturbed by the odious language and anti-medicare rhetoric, they deplored ‘the unwillingness of some groups within the profession to accept the critical and natural responsibility of physicians in the stewardship of our publicly funded health care system’ (my emphasis). Stewards, here they are at last! Familiar names appear among the signatories: members of the MRG and CDM, and many young people, still fighting for medicare against organized medicine – and now also against the organized fringe groups.

Furthermore, while I was writing this paper, another group has formed, comprised of resident doctors, mostly from family medicine and pediatrics. They first met on 22 February 2017 at St. Michael’s Hospital as ‘Ontario Doctors for Healthcare Stewardship’. More stewards! The initial announcement called for support to alter the nasty tone of the debate, while recognizing the frustrations of practitioners coping with fiscal limitations (Langer, Reference Langer2017). However, within 2 days they had changed their name to ‘Doctors for Responsible Health Care (DRHC)’ (2017).Footnote 6 The name change was deliberate. Perhaps in dropping ‘stewardship’, they were avoiding ivory-tower stuffiness, didactic sanctimoniousness, or awkward prose. But I wonder if the word, ‘steward’ is too servile, too menial, like a butler or a ‘Manager’ and not enough like a ‘Leader’ to be attractive to some colleagues?

And where was CDM on this issue? Why is a yet another new group needed? Is it a jurisdictional matter, because CDM is conspicuously national and this problem is provincial? Is CDM spread too thin? Is the Ontario debate simply too ugly and too vast to risk a clear position? Again, like all its alphabetical predecessors, at its website launched on 7 March 2017, DRHC declares its support for medicare and fair compensation for physicians and its opposition to user fees, extra billing and strikes for doctors (although not for all workers). An idealistic, youthful, phoenix-like successor to the MRG – obliged to tilt against the profession once again.

Stewardship is at the heart of the matter, says health-policy analyst and long-time member of the MRG, Michael Rachlis. But stewardship in Canada is defeated by persistent ‘medical dominance’ (Bourgeault and Mulvale, Reference Bourgeault and Mulvale2006). Despite the rhetoric of ‘patient-centeredness’, doctors determine their own wages, allocate resources and are rewarded for consuming them, which leads to inefficiencies, ineffectiveness, and waste. Only a handful of isolated entities bother to make clinical governance, improved health, and resource conservation matters for practice review and physician payment. Rachlis names them, a few come from elsewhere: the Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Choosing Wisely Canada; Hamilton’s Mental Health and Addiction Services, Cancer Care Ontario. Stewardship would reorganize delivery mechanisms to fix this problem – not unit-by-unit – but nation-wide. However, the notion is so far beneath the radar of the public, as well as physicians, that the conversation has not even started. Rachlis has been talking about the same concerns for 40 years.

Stewardship: an example

We have seen that two themes characterize the tiny minority of physicians who strove and continue to strive within our medicare system: youthful idealism and a pragmatic desire to improve health outcomes on a population scale. Going back to Macleod, Sigerist, Douglas and Hall, the social determinants of health have long been recognized as just as important, if not more important to health than numbers of physicians or the availability of MRI machines. In the upheaval following Brian Day’s election as CMA president, the CHC, together with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, sponsored ‘SOS Medicare -2’, a conference, held on 3–4 May 2007 in Regina, Saskatchewan, the ‘cradle’ of medicare, Old non-medical stalwarts were invited to deliberate the challenges and future of health care: Monique Bégin, Roy Romanow, Shirley Douglas, Tom Kent, Alan Blakeney and Stephen Lewis – and even some famous Americans doctors, such as Marcia Angell and Arnold Relman; however, Canadian physicians were conspicuous by their absence, with the exception of MRG’s Rachlis. More than 600 people attended and 40 papers were read. Six months later, the proceedings, edited by Bruce Campbell and Greg Marchildon, were published; several speeches can also be found online (Campbell and Marchildon, Reference Campbell and Marchildon2007). One of the most exciting outcomes of this gathering was the urge to expand medicare beyond doctors and hospitals to the ‘second stage’ by incorporating the social determinants of health within the five pillars of the Canada Health Act, as elements of access and universality (Rachlis, Reference Rachlis2007).

Work on the social determinants is being neglected in Canada because of the louder noise coming from physicians and acute-care hospitals. They include housing, chronic care facilities, home care, child poverty, food security, addiction, dental care, mental health care, adult literacy, pharmacare and water on First Nation reserves. Doctors who purport to stand for the well-being of citizens should want to improve Canada’s social determinants. They could help by recognizing that government budgets are finite. What if physicians were to pause, to withhold demands for higher income until certain specific social issues were solved? Emergency physician Dr Alain Vadeboncoeur of MQRP went further, suggesting that a mere 1%, self-imposed tithe of medical income in Quebec would generate a sobering $60 million to be applied to other problems. He argued that it would be far preferable to health-denying mechanisms, such as user fees (Vadeboncoeur, Reference Vadeboncoeur2015). In Ontario, that tiny slice would translate to more than $100 million annually – real money. Could doctors not recover a sense of collaboration, advocacy and professional dignity in successively adopting just one or another of these long-neglected issues and leveraging it through to a solution with embargos on raising their already generous wages? It could be done even in the doctor-dominated system that we still have.

Let us pick just one example. The number of drinking water advisories on First Nation reservations is a national disgrace. At the Health Canada website, such advisories hover at around 130 affecting 90 or more First Nation communities; many have remained virtually unchanged for decades (Health Canada, 2017). But that’s not the whole story because British Columbia tracks its water advisories separately by regions and sub-regions at a labyrinthine website, without summaries, totals or durations, making it impossible to determine which warnings affect First Nations (British Columbia, 2017). Consequently, we have only a partial view of the extent of the problem nationally. The situation has provoked many calls for action and research (Human Rights Watch, 2016). The causes are numerous but finite: they can be microbial or toxicological, stemming from long-standing industrial pollution, failed purification systems or inadequate sewage treatment. Years of outraged commentary and international scrutiny are slowly beginning to pay off. The federal budget of March 2016 promised $2.2 billion over 5 years to address the problem (Canada, 2016). Meanwhile in February 2017, media reported on a water purification system purchased for Pic Mobert First Nation in northern Ontario at a cost of $13 million in federal funds. The investigators mused over the cost and the lack of trained personnel and money to maintain the new system in a community with 60% (Choi, Reference Choi2017; McClearn, Reference McClearn2017). The reports implied that the expensive investment would be wasted, leaving observers to wonder if $2.2 billion will be enough.

Canada has the technological, social and human capital to solve this water problem. For example, we hear with pride of the Disaster Assistance Response Team that sets up its reverse osmosis unit to purify about to 50,000 litres of water daily in the complex emergency conditions of earthquakes, floods and hurricanes. Can these processes not be adapted for isolated communities living in peace and quiet? What if organized medicine decided to withhold its demands for fee increases until this fundamental health problem is solved? With physician advocacy, savings could be diverted to the necessary technical and human resources. Such a campaign can work only with a single-payer system and a profession that not only benefits from that system, but accepts its many privileges not as entitlement, but as a mark of its responsibility to work toward health equality.

Conclusion

From Douglas’s quirky medical champions – Maclean and Sigerist – to CAMSI, MRG, CDM, MQRP and DRHC, a small but energetic minority of doctors have defended medicare. Poignantly, most of the MRG, CDM or DRHC leaders with whom I have spoken had never heard of CAMSI; yet, they share the characteristics, the mission and the personal risks that attend to speaking evidence to organized power. It seems with each new crisis, another group of idealistic young doctors eventually stands up on behalf of patients to oppose their profession’s grasping self-interest, only to be replaced a few decades later by the next equally idealistic group, younger and better constituted for the times, but –sadly – still obliged to fight on two fronts for medicare and against organized medicine. When, and if, they can finally move on to the more difficult and more important ‘second stage’ task of promoting health through medicare, that, to my mind, would be stewardship.

Acknowledgments

This paper has benefited from the generosity, memories and insights of Philip Berger, Monika Dutt, Brian Gibson, Gordon Guyatt, Joel Lexchin, Janet E. Maher, Michael Rachlis, and Lauren Welsh. The author thanks them all and Robert David Wolfe as well as two anonymous readers for comments on an earlier version