British settler colonies, colonies of occupation, and plantation colonies were built on unequal relationships between colonizer and colonized, and entailed the correlative exploitation of distant land, labor, and other resources.Footnote 1 While distinguishing between them is useful, the terms themselves are Eurocentric constructs, even as they denote material realities; the lines between them are not hard and fast; and no two colonies were exactly alike. British residents of colonies of occupation (like India and Hong Kong) were temporary and largely male. These merchants, missionaries, soldiers, and administrators (who, particularly in the latter two cases, sometimes moved between colonies) formed a “thin white line” of control over indigenous populations.Footnote 2 British residents of planation colonies (like those in the Caribbean) were only somewhat more permanent. These mostly upper-class plantation owners often spent months or even years in Britain, where their wives and children, if they had them, were as likely as not to reside. Because the Caribbean's indigenous population had been all but destroyed through contact with earlier European settlers, the British generated a labor force by importing Africans as slaves and Indians as indentured servants. Though non-whites outnumbered whites significantly, resistance—to poor working conditions, slavery (pre-1833), and other forms of inequality—was met with brutal reprisal. As in colonies of occupation, resources flowed out.

Settler colonies (in the nineteenth century, primarily Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa) were distinct from colonies of occupation and plantation colonies in that large numbers of British men, women, and children emigrated to them with the intent to remain permanently. These several million Britons (more than 1.5 million during Queen Victoria's reign alone) of varied classes and occupations sought to build futures in their new homes not only for themselves, but for their descendants, as well.Footnote 3 Like those (primarily) sojourning Britons in other types of colonies, they facilitated colonial Anglicization through the dissemination of British values and customs, but they also reproduced those values across generations (who long continued to see themselves as British, even as they developed hybrid identities). And while resources were extracted to Britain, they also accrued to settlers.

Settler colonies were a site of “constant negotiation.”Footnote 4 While colonial discourse framed settler lands as empty—there for the taking—colonists, administrators, and soldiers seized it from its indigenous (and in some instances also European-descended) denizens, displacing them through a variety of means.Footnote 5 As Patrick Wolfe explained in a 2012 interview: “Settler-colonialism is a form of colonialism that is exclusive. It's a ‘winner take all,’ a zero-sum game, whereby outsiders come to a country, and seek to take it away from the people who already live there, remove them, replace them, and displace them, … and make it their own.”Footnote 6 Tracey Banivanua Mar and Penelope Edmonds elaborate: “policies of assimilation, merging, absorption, [and] protection”—from intermarriage to the forced removal of children from their families—“heralded a range of legally sanctioned practices whose goal of abolishing Indigenous peoples’ languages, histories and identities are increasingly identified as genocidal.”Footnote 7 Indigenous groups responded to British settlers and policies with multiple forms of resistance, negotiation, and, in some instances, (largely coerced) cooperation.Footnote 8 Not only were indigenous-colonial relations fundamental to settler identity, they were, as Annie E. Coombes has argued, “the historical factor which … ultimately shaped the cultural and political character of the new nations.”Footnote 9 From this vantage point, apartheid South Africa was not an exception; it was the end of a spectrum.

The terminology used to describe settler colonialism has shifted over time. “What is now called settler colonialism was known in the nineteenth century as ‘colonization’” and settler colonies were simply called colonies.Footnote 10 Today's umbrella term, imperialism, “the practice, the theory, and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory,” was known as colonialism.Footnote 11 Though even today colonialism is sometimes used in this older, broader sense, it more often denotes, in the words of Edward Said, “the implanting of settlements on a distant territory”—in short, settler colonialism.Footnote 12 Said himself had surprisingly little to say about settler colonialism, a term that emerged in Australia in the 1920s, “to distinguish it from convict colonialism.”Footnote 13 The index of Orientalism—which of course is primarily about the Middle (or Near) East—contains no entries for settler colonialism, settler, colonialism, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, emigration, or immigration.Footnote 14 And while colonialism occupies twenty-eight pages in Culture and Imperialism, settler, settler colonialism, emigration, immigration, and New Zealand still make no appearance; the entry for Australia lists twenty-one pages, Canada, six, and South Africa, five. When Said did discuss settler colonialism, he tended to fold it into the broader discourse of imperialism, as would most postcolonial scholars who followed in his immediate wake. Other scholars read settler colonial histories and literatures as part of national narratives.

Only in the last two decades has settler colonialism emerged as its own field, one that engages settler colonial histories and literatures beyond (though not apart from) national contexts and views them as distinct from (though not without shared characteristics of) broader imperial discourse. Important early texts include Daiva Stasiulis and Nira Yuval-Davis's edited collection, Unsettling Settler Societies: Articulations of Gender, Race, Ethnicity and Class and Patrick Wolfe's Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event, in which he argues that “invasion is a structure not an event.”Footnote 15 There have been several excellent monographs and collections on settler colonialism in the last few years, mostly by historians. The most influential by far is James Belich's Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Anglo-World. Notable recent work in other disciplines includes John Darwin's The Empire Project, an economic study; analyses of settler narratives by Jude Piesse, Tamara Wagner, and the contributors to Victorian Settler Narratives (which Wagner edited); and Fiona Bateman and Lionel Pilkington's multidisciplinary collection, Studies in Settler Colonialism.Footnote 16

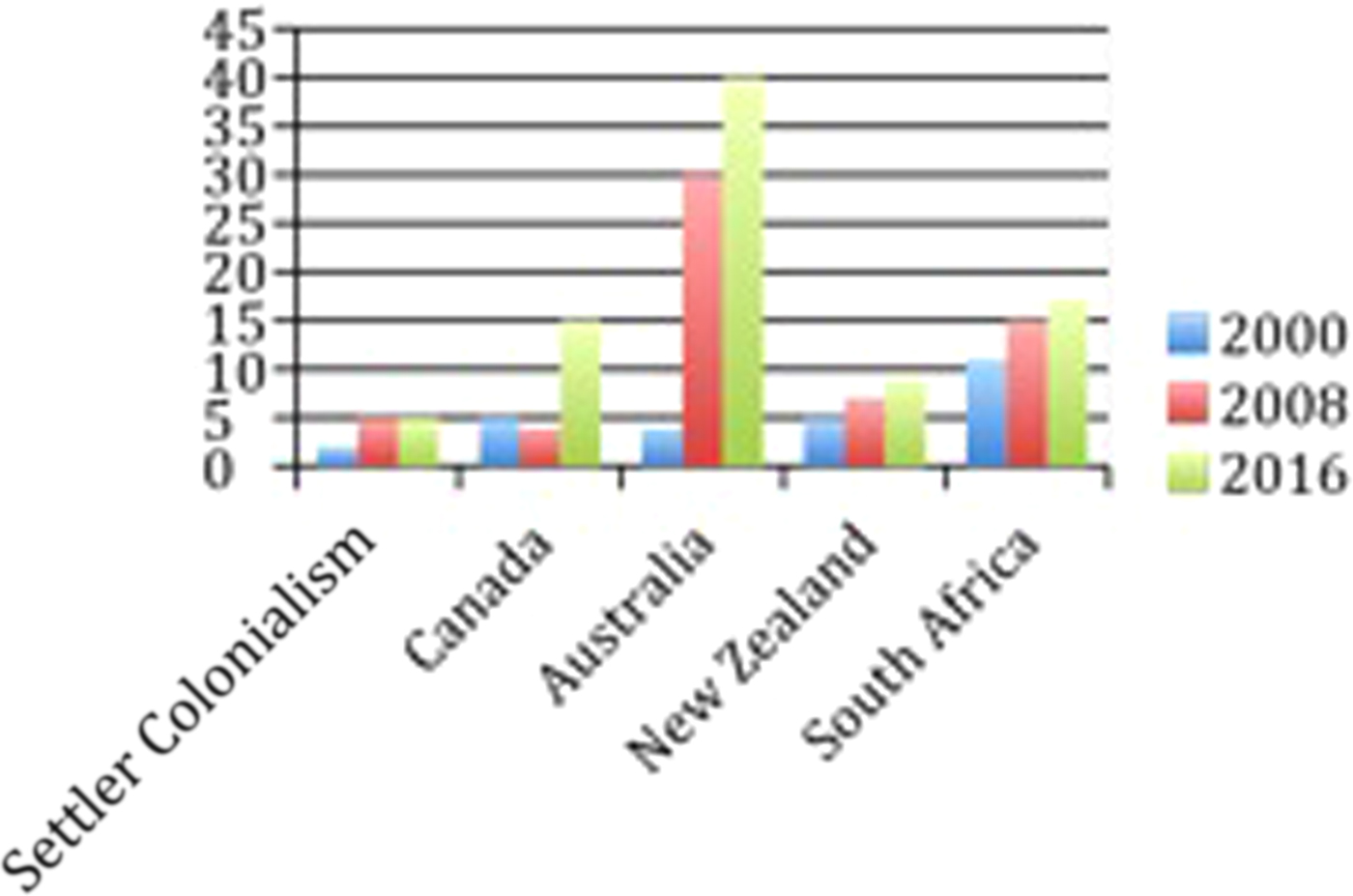

The Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, an online journal begun in 1999, published a special issue on settler colonialism in 2003. Edited by Fiona Paisley, it “set out to contribute to … intracolonial scholarship on white settler colonialisms and the colonial turn,” which “coalesce[s] around an awareness that histories cut across and between not only … settler colonies but [also] settler and [other] colonies, and … settler/colonial and metropolitan cultures.”Footnote 17 Each year since its inception, JCCH has published a bibliography of the previous year's work on “colonialism and imperialism.” Figures 1 and 2, based on data from the 2001, 2009, and 2017 bibliographies, reflect my rough count of journal articles and books focused on or engaging heavily with British settler colonialism in the Victorian period.Footnote 18 As these figures illustrate the field's growth, so, too, does the 2011 launch of Settler Colonial Studies, an online journal edited by Edward Cavanagh and Lorenzo Veracini, who also gave us the field's first handbook in 2016: The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism.

Figure 1. Rough count of relevant journal articles listed in JCCH bibliography, 2000–16.

Figure 2. Rough count of relevant books listed in JCCH bibliography, 2000–16.

Since 1998 several collections have been published based on the idea of “the British World,” “a framework … concerned with exploring the networks and flows of people, goods and ideas that connected these various settler colonial spaces and places.”Footnote 19 In common with the new imperial history—which is more theoretically informed, interdisciplinary, and postcolonial in its approach—British World historiography suggests that “the seeds of transnationalism” are rooted in imperialism.Footnote 20 But where the new imperial history foregrounds the violence of colonialism, British World historiography, until very recently, has tended to give this definitional aspect short shrift.

Given the waves of white nationalism that have so recently and publically resurfaced in erstwhile metropoles and colonies alike, attention to the violence, erasure, and genocide that were part and parcel of settler colonialism is as urgent as ever. Much remains to be done in the still growing field of settler colonialism. In particular, there is room for more extensive study of South Africa; literary analyses that consider both colony and metropole; and comparative analyses, both between British settler colonies and between British and other settler colonies.