1. Introduction

This article concerns two migration-based varieties of Karelian, Tver’ Karelian in Russia and Border Karelian in Finland, which have a fairly similar origin but which developed independently of each other for several centuries (see Figure 1). The focus lies on Tver’ Karelian, an isolated enclave around the city of Tver’. The Tver’ Karelian variety originated in the seventeenth century due to several migration waves from Karelia, and the language has been maintained up to the present day. The Border Karelian dialects developed in the region named Border Karelia, which belonged to Finland until 1944. For four hundred years these varieties have been evolving in different contact-linguistic settings; Tver’ Karelians have been surrounded by Russians and their language has been heavily influenced by Russian, whereas the Border Karelian variety has received Russian influence from the east and increasing Finnish influence from the west. As a result, Tver’ Karelian differs from Border Karelian phonetically, especially due to increased use of hissing sibilants and stronger palatalisation of consonants. In addition, lexical borrowing from Russian has been more extensive in the Tver’ area. The existence of these two varieties offers an eminent opportunity to study the process of dialectal diversification and the speakers’ perceptions of this process.

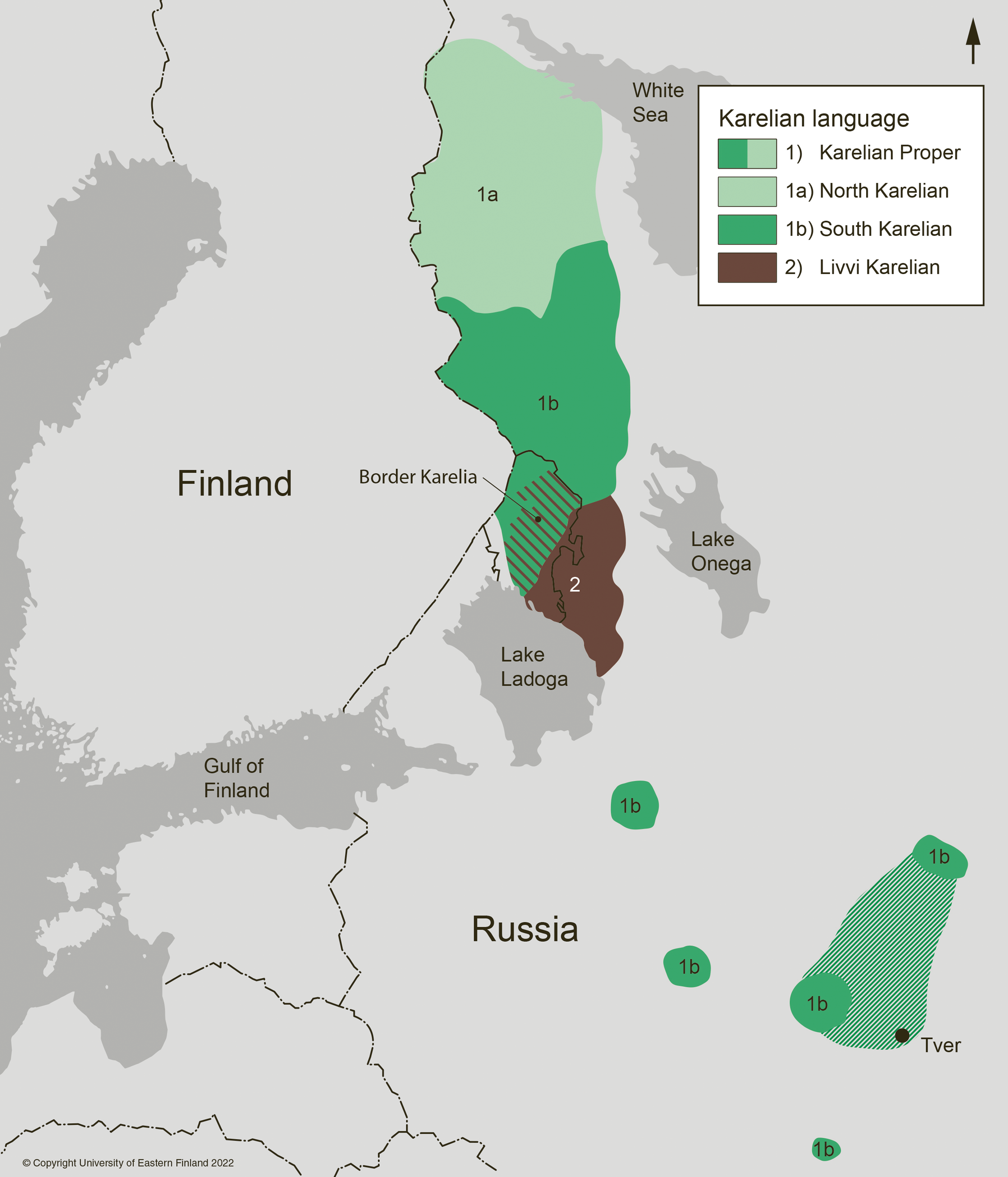

Figure 1. The Karelian varieties. Border Karelia is the area situated inside the borders marked by black lines: in this area, both South Karelian and Livvi Karelian were spoken, and the westernmost parts were inhabited by speakers of Finnish.

Our study approaches the perceptions that the Tver’ Karelians have of their own Karelian variety, on one hand, and of the Border Karelian variety spoken in Finland, on the other hand. The data were obtained by applying a folk linguistic listening task in an interview setting in order to elicit observations and reflections of dialectal differences. The respondents were asked to listen to two speech samples, one of which represented old Tver’ Karelian and the other old Border Karelian, followed by questions concerning their perceptions of the samples. The study aims to answer the following research questions.

-

(i) To what extent do the Tver’ Karelians recognise and understand the Tver’ Karelian and Border Karelian samples recorded 60 years ago?

-

(ii) Which linguistic features do they pay attention to and how could their observations be explained?

The article is structured as follows. The historical setting of Tver’ Karelian is presented in Section 2, compared with Border Karelian, and Section 3 introduces the theoretical background of the study. In Section 4 we describe the elicitation method and the way it was applied during field work in the Tver’ region. The results concerning the observation after listening to the Tver’ Karelian and Border Karelian samples are presented in Sections 5 and 6. Finally, we discuss the significance of the results in Section 7.

2. Karelian varieties in Tver’ and in Finland

Karelian is a small, endangered Finnic language spoken in Russia and in Finland. It is traditionally divided into two major dialects, Karelian Proper and Livvi (Olonets) Karelian, the first of which is further divided into North (Viena) Karelian and South Karelian (see Figure 1 in Section 1). (For an introduction to the Karelian language and its dialects, see Sarhimaa Reference Sarhimaa, Bakró-Nagy, Laakso and Skribnik2022.) Of the Karelian varieties, South Karelian is at the centre of our interest: it is the dialect that, in the seventeenth century, was spoken in the easternmost reaches of Finland, where the Tver’ Karelian variety has its origins. South Karelian was also spoken in Finland’s Border Karelia as a regional variety until 1944. In other words, both Tver’ Karelian and Border Karelian have shared roots but have been developing in different directions during the last centuries.

Tver’ Karelian has been spoken in Tver’ Oblast in inner Russia, northwest of Moscow, as an isolated enclave in the middle of a Russian-speaking environment (see Figure 1). The variety originated during the seventeenth century due to a migration of Karelians from Eastern Finland and Border Karelia. These areas had belonged to Russia and they had been inhabited by speakers of Karelian, but in the treaty of Stolbovo (1617) they were incorporated into the Swedish empire. The Karelians had adopted the Christian faith in its eastern form and belonged to the Orthodox Church. When they became subjects of the Swedish Crown, which at this point professed Lutheranism, they were faced with religious oppression. They were also met with increased taxes and restrictions on trade, making their living harder. At the same time, the areas around the city of Tver’ had been deserted during a war and Russia encouraged migration to the area by offering exemption from taxes and other support. This resulted in a migration where a significant part of the Karelian-speaking population moved to the Russian interior, and most of them found new domiciles in the Tver’ region; the number of migrants was around 25,000–30,000 (for further details on the migration, see Zherbin Reference Zherbin1956, Saloheimo Reference Saloheimo2010 and Savinova & Stepanova Reference Savinova and Stepanova2017).

The new life in the Tver’ region proved to be fairly prosperous: the soil was fertile and the Karelians became quite wealthy peasants. They lived in Karelian-speaking villages, and in the midst of Russian-speaking areas they were able to maintain their language. The rural way of life with tight-knit, mostly monolingual Karelian communities protected the language (see e.g. Sarhimaa & Siilin Reference Sarhimaa and Siilin1994:274). In the course of the subsequent centuries, Tver’ Karelian developed into a Karelian variety of its own (see e.g. Virtaranta & Virtaranta Reference Virtaranta and Virtaranta1986, Koivisto Reference Koivisto, Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018:61–62, 2022). The number of Karelians grew steadily until it reached its peak during the 1920s and 1930s; at the peak, there were about 140,000 Karelian speakers – more than in Russian Karelia (Laakso et al. Reference Laakso, Sarhimaa, Spiliopoulou Åkermark and Toivanen2016:97). However, similarly to most minorities in Russia, the number of Karelian speakers has been decreasing dramatically since World War II. According to the 2010 census there were 7,400 Karelians in Tver’, and the recent 2020 census shows even lower numbers: 2,764 ethnic Karelians of which the number of Karelian speakers is 1,845 (for the 2020 census, see https://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn_popul). How accurate these numbers are is a matter of dispute (for a short discussion see Antonova Reference Antonova2023), and recently Novak (Reference Novak2022) has estimated that the number of speakers is 3,000–4,000. Undeniably, the language is critically endangered, and most speakers belong to the oldest generations. Tver’ Karelian has been divided into three dialects, of which the Tolmachi dialect in the centre of the oblast is the most viable one. The southernmost Dërzha dialect is already extinct and the northern dialect is spoken by only 5% of the Tver’ Karelians (Novak Reference Novak2019:229).

The other area relevant to the present study is Border Karelia, the former Eastern Finnish region situated in the vicinity of the Russian border. Originally, Border Karelia was part of the larger area where the South Karelian variety was spoken (see Figure 1 in Section 1). Until the seventeenth century the area belonged to Russia, but it was then incorporated into Sweden after the aforementioned treaty of Stolbovo (1617). While many Karelians began to move to inner Russia, Border Karelia mostly retained its Karelian-speaking inhabitants; the westernmost area, however, started to get a new, Finnish speaking population. Border Karelia was part of Finland during the era of Swedish rule and during the time when Finland was an autonomous grand duchy of the Russian empire (1809–1917), as well as the first decades of independence (1917–1944). Karelian was spoken as a regional language, and as it had close contact with Eastern Finnish dialects, it began to receive influence from Finnish. After World War II, Border Karelia was ceded to the Soviet Union and its Karelian inhabitants were resettled in various parts of Finland, making Karelian a non-regional minority language. (For the Border Karelian variety, see Koivisto Reference Koivisto, Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018.) After the war and under heavy pressure from the majority population, the Karelians have largely shifted to using Finnish and ceased to transmit their heritage language to younger generations (see e.g. Laakso et al. Reference Laakso, Sarhimaa, Spiliopoulou Åkermark and Toivanen2016:104–115, Sarhimaa Reference Sarhimaa2017). At present Karelian is an endangered language in Finland, but it has more speakers than was previously assumed: the latest estimate of the number of Karelian speakers is 11,000 and about 20,000 Finnish Karelians can understand Karelian (Sarhimaa Reference Sarhimaa2017:115).

3. Theoretical and methodological background

The present study is anchored in folk linguistics, a field of sociolinguistics that is interested in laymen’s (non-linguists’) language regard and knowledge of language. Folk linguistics became established as a research field in the 1980s in the United States due to the seminal work of Dennis R. Preston, but it has had predecessors: studies that were essentially folk linguistic in nature were conducted in the Netherlands and Japan in the middle of the twentieth century (Preston Reference Preston and Preston1999b). Over the course of the decades to follow, the folk linguistic approach has spread to different parts of the world, and in Finland, folk linguistics and its subfield, perceptual dialectology, has been deployed since the beginning of the 2000s.

Within folk linguistics, research is focused on how non-linguists observe language, how they speak about their perceptions, what kind of metalanguage they use, and what kind of attitudes they have towards language varieties and linguistic features. Answers to these questions have been obtained by using various methods. The methodological tool kit has included drawing mental maps of the dialect areas, recognising samples of dialect speech, imitation tests as well as thematic interviews, and free conversation concerning different varieties and their speakers (Preston Reference Preston1999a, Niedzielski & Preston Reference Niedzielski and Preston2000, Long & Preston Reference Long and Preston2002, Cramer Reference Cramer2016). In Finland, researchers have also studied texts that non-linguists have written by using a dialect, translations into a dialect, and dialect imitations that have spread as a form of folklore. Additional methods have included ranking Finnish cities in order of strength of dialect and self-reporting of one’s own dialect (Mielikäinen & Palander Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2014:21−25).

Folk linguistics examines the language users’ awareness of their own language and the language spoken by others. Preston (Reference Preston1996, Reference Preston and Brown2006) has classified these observations into four categories. First, the researchers can study what kind of linguistic phenomena the laymen are observing – in other words, what kind of features they are aware of, and which features are thus available to them. In Preston’s terms, we can speak about the availability of the linguistic features. The observations vary individually: some are able to perceive small, phonetic differences in pronunciation whereas others only pay attention to larger items such as lexemes. The second category is accuracy, which refers to the relation between the laymen’s observations and the results revealed by linguistic research. If the non-linguists’ observations are in line with the linguists’ knowledge of language, they are termed accurate, and if they deviate from it, they are termed inaccurate. The third category, detail, is related to the detailed vs. global nature of the observations; an example of a general observation is provided by those non-linguists who describe a dialect as ‘hard’ but who are not able to specify the features that create the impression of ‘hardness’. Finally, the category of control refers to the non-linguists’ ability to imitate the dialect or its features (Preston Reference Preston1996, Reference Preston and Brown2006:523–524).

So far, folk linguistics has mainly concerned the dialects or other varieties of majority languages and it has not often been applied to minority language settings. There are, however, studies that have approached language awareness and linguistic attitudes among the speakers of Kurdish (Eppler & Benedikt Reference Eppler and Benedikt2017), Basque (Lasagabaster Reference Lasagabaster, Garrett and Cots2018), the Rusyn language in Ukraine (Schimon & Rabus Reference Schimon and Rabus2016), and languages spoken in Hong Kong (Albury & Diaz Reference Albury and Diaz2021); the focus has been on how non-linguists perceive the geographical areas where a minority language is spoken. In the context of the Galician language in Spain, researchers have studied linguistic identity and the right to speak the minority language in cases where the minority language is not the speaker’s first language but has been acquired after migrating to Galicia (Bermingham Reference Bermingham, Murchadha, Hornsby and Moriarty2018, O’Rourke & Ramallo Reference O’Rourke, Ramallo, Cassie Smith-Christmas, Murchadha and Moriarty2018). A further aspect studied has been the Maori speakers’ views of language policy in New Zealand (Albury Reference Albury2017, Reference Albury2018).

The studies of the Karelian language conducted by Finnish researchers form their own entity in folk linguistics. The linguistic and sociolinguistic settings are unique to all the minority languages, and the ways in which the minority languages are perceived and observed vary. Research into Karelian has made use of folk linguistic methods but applied and adjusted them to fit this particular linguistic context. Previous research has focused on what Finns with and without Karelian roots mean by the term Karelian, what linguistic features they assign to Karelian, and how they recognise samples of Karelian (Palander Reference Palander2015; Riionheimo & Palander Reference Riionheimo and Palander2017, Reference Riionheimo, Palander, Kolehmainen, Riionheimo and Uusitupa2020; Palander & Riionheimo Reference Palander, Riionheimo, Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018a, Reference Palander and Riionheimo2018b). Furthermore, there are a few studies concerning the language regard of North (Viena) Karelians living in Russia, how they value the Karelian dialects in relation to each other and to the Finnish and Russian languages (Kunnas Reference Kunnas and Suutari2013), and how the North Karelians recognise different varieties of Karelian (Kunnas Reference Kunnas, Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018).

In the present study, we apply a form of recognition task in order to examine how well the Tver’ Karelians, who have lived as an isolated enclave, recognise their own Karelian variety and the Karelian variety spoken in Border Karelia – two varieties which have common roots. Both varieties have been shaped by language contact: Tver’ Karelians have had intensive contact with Russian, and the Border Karelian variety has had contact with both Russian and Finnish. We are interested in how the different contact settings and their linguistic outcomes are reflected in the way the speakers perceive the Karelian varieties; this study was designed to focus on language awareness, not dialect attitudes or other related phenomena. Previously, Karelian has not been studied from this kind of contact-linguistic perspective.

4. Applying the listening task in the Karelian context

The data for the present study were gathered in rural areas in Tver’ Oblast during two field trips in 2018 and 2019. We visited Karelian villages where Karelian had previously been spoken as the primary language. Today these villages are partly abandoned: most of the permanent habitants belong to older generations, and because of urbanisation and shutdown of local collective farms after perestroika, their children have moved elsewhere to receive education and to find job opportunities. Often Russians have bought old Karelian properties as summer houses, and in the villages Russian is now the most commonly used language. Furthermore, it seemed to us that Russian is the dominant language for most of the Karelians as well, and they mostly use Russian when communicating with each other. In this section we describe our respondents, depict the listening task, and present the samples used in the task.

4.1 The Tver’ Karelian respondents

We had a local contact who had approached the Karelian inhabitants beforehand and organised our meetings; these people were ethnically Karelian and had learned (at least some) Karelian in the village during their childhood. Their skills in Karelian formed a continuum from fluent competence to ‘passive’ knowledge, i.e. fairly good receptive skills. Varying forms of linguistic skills are a typical feature among the speakers of an endangered language, and the ‘imperfect’ speakers have been described by terms such as rememberers (e.g. Grinevald & Bert Reference Grinevald, Bert, Austin and Sallabank2011:51, Sallabank Reference Sallabank2013:14) or latent speakers (Basham & Fathman Reference Basham and Fathman2008). However, we prefer the more ‘neutral’ term heritage speaker, as this term can be used in a broad sense to refer to a wide range of language skills. Some of our respondents had taken part in Karelian language clubs but they had not received formal instruction in their heritage language. Most of them did not read or write in Karelian, and the Tver’ Karelian written standard, which uses the Latin script, is not very familiar to people who are used to reading and writing in the Cyrillic script.

Another feature typical of endangered-language communities is bilingualism: all the Tver’ Karelians are bilingual, and they have acquired Russian as their other native language. Since Russian is the dominant language in all domains outside the home and the use of Karelian is mostly restricted to the domestic sphere, it is not surprising that Russian is the dominant language in their life. Furthermore, it is extremely common for Tver’ Karelians to use Russian elements when conversing in Karelian, and code-switching is frequent (for a recent study of Russian influence and code-switching, see Tavi Reference Tavi2022). In our research team we had a policy to respect the way the respondents used all their linguistic resources. Thus we did not discourage the use of Russian during the interviews, but saw the intertwining of Karelian and Russian elements as a natural phenomenon in this bilingual setting.

Table 1 above presents the municipalities or villages where the interviews were conducted; we visited several places in three raions (districts; Likhoslavl’, Maksatikha, and Spirovo), which all belong to the area of the Tolmachi dialect, the major dialect of Tver’ Karelian (see Figure 2). We numbered the respondents in the order in which we interviewed them (e.g. Mikshino1 and Mikshino2). Referring to these villages is made complicated by the fact that they usually have two names: an official Russian name (written in Cyrillic script) and an unofficial Karelian name (mostly used in a spoken form). The Cyrillic characters, in turn, can be transliterated into the Latin alphabet in several ways. For the purposes of the present article, we have used the Russian names and romanised them by using the BGN/PCGN system.

Table 1. The home villages of the respondents

Figure 2. The location of the Karelian villages mentioned in this article. The arrows indicate that the place is located outside this map.

We did not select our respondents in any particular way, but interviewed all the Karelians who had gathered for these meetings and were willing to take part in our research. The aim of the research setting was to find out how Tver’ Karelians living in these villages recognise the samples, and thus the central variable in our study is the home village. The total number of respondents was 30 and they were all middle-aged or older; the oldest ones were aged around 80 or 90 years.Footnote 1 For the most part, the respondents had been born in the village where they were interviewed and had lived there for decades; some of them had studied or worked elsewhere at some point in their life, but this did not affect their observations of Karelian because they had only used Russian in their schools or workplaces.

4.2 The listening task

We conducted a small interview with each respondent. At the beginning, we introduced the listening task and the purpose of our research, and the respondents signed a consent form (written in Russian). The respondents first listened to the Tver’ Karelian sample (described in Section 4.3) and answered the following questions: (i) where do people speak in the same way as in the sample, (ii) did they understand what the speaker said in the sample, (iii) could they tell us the content of the sample in their own words in Karelian or in Russian, and (iv) were all the words in the sample familiar to them. Then the Border Karelian sample was played, and the same questions were answered; this time, we also asked how the two samples differed from each other. Usually the samples were played twice, especially in the cases where the respondent had difficulties remembering any details of the sample. After hearing the answers we sometimes made additional questions, and some respondents began to compare the sample with the dialect of their own village or to spontaneously share their experiences on dialectal differences, offering observations that are extremely valuable from the perspective of folk linguistic research. All the interviews were recorded by using a digital recorder in order to save the exact answers. The interviews were rather short, ranging from 10 to 30 minutes.

We aimed to interview the respondents in Karelian but this was not always possible; our Finnish accent seemed to be confusing for Tver’ Karelians, whose own Karelian variety is phonetically heavily influenced by Russian. We also had interviewees who didn’t feel comfortable speaking Karelian, and we always gave them the option to answer in Russian. Our own skills in Russian are limited, but during the first field trip we had the help of a local guide who spoke Russian and English; we presented the questions in English and the guide translated them into Russian and also interpreted the answers into English. In the second trip we had a member of our research team translate the questions from Finnish to Russian. All the interviews were recorded, and afterwards the Russian-language parts were checked by a colleague who is a native speaker of Russian and Karelian.

The interview situations varied considerably. In some cases we conducted the proceedings at the respondent’s home and did a private interview; sometimes there were other family members present as well. Often we carried out our interviews in the place where our contact had asked the villagers to gather (at a school building, in a library, or in the village club). These situations were slightly chaotic, and it was not always possible to use a separate room. There were occasions when other respondents, who were waiting for their turn, may have heard our conversation, and sometimes we could hear them commenting on the answers in the background. However, this did not seem to affect the conceptions of the respondents, and no one repeated the answers presented by an earlier interviewee. The samples were played through headphones and thus every respondent only heard the samples during their own interview.

Similar recognition tests have been used in folk linguistic studies before. For instance, Dennis R. Preston (Reference Preston and Ammon1989), working with respondents living in Michigan and Indiana, played nine samples in which the speakers were natives of a line that runs through the USA from north (Michigan) to south (Alabama); the respondents were asked to connect each speaker to a city in a list that was given to them. On account of the results, it was possible to see where the respondents’ perceptions pinpointed dialect boundaries (Preston Reference Preston and Ammon1989:345–352). By using the same data, researchers could also examine whether monophthongisation of the /ay/ diphthong had an effect on these perceptions (Plichta & Preston Reference Plichta and Preston2005). In Finland, Vaattovaara (Reference Vaattovaara2009:136–143) used a listening task to investigate how young people living in the area of the Far North differentiate their own dialect and the neighbouring dialects. Vaattovaara and Halonen (Reference Vaattovaara and Halonen2015) have applied a recognition task to examine what linguistic features are reported by the respondents to reveal that the sample represents the Helsinki metropolitan area. Riionheimo and Palander (Reference Riionheimo and Palander2017), in turn, have used a listening task when investigating to what extent Finnish university students recognised the dialect of Border Karelia. In all these cases the focus has been on recognising the areal background of the speakers, and the present study follows this tradition.

4.3 The Tver’ Karelian and Border Karelian samples

Two samples of recorded speech were used to elicit observations and reflections on areal variation of Karelian. Both samples were recorded in the 1960s by Finnish researchers and their length was about one minute. The first sample represents Tver’ Karelian; the speaker is a woman born in 1905 and interviewed in 1963 in Tolmachi (see Figure 2 in Section 4.1). The sample is presented below (example (1)), written by adapting the orthography of the present-day Karelian standard with some modifications;Footnote 2 the same practice has been applied to the excerpts of the interview data in Sections 5 and 6.

A prominent feature of this sample is Russian influence in pronunciation, especially strong palatalisation of consonants and the use of hissing sibilants and voiced plosives (all bolded in example (1)). All Karelian varieties have been in close contact with Russian but the Russian impact is strongest in Tver’ Karelian. Phonetic influence is suggested to have originated via extensive lexical borrowing from Russian, and it has become even stronger since the beginning of the twentieth century along with widespread Karelian–Russian bilingualism (Novak Reference Novak2019). Novak (Reference Novak2019) describes how the Tver’ Karelian vowel and consonant systems have converged towards the Russian ones; furthermore, Russian influence has induced linguistic features that separate Tver’ Karelian into three subgroups.

The second sample (see example (2)) was recorded in Finland in 1961; the interviewee was a man who had been born in Border Karelia in the municipality of Suistamo in 1890. Finnish influence was common in the western parts of Border Karelia where Suistamo is situated (Uusitupa, Koivisto & Palander Reference Uusitupa, Koivisto and Palander2017). The sample differs phonetically from the Tver’ Karelian sample: there is much less influence from Russian, whereas the Finnish influence is evident, especially on the phonetic level (e.g. there is much less palatalisation and often voiceless plosives are used instead of voiced ones; these voiceless plosives are bolded in the sample) but also in the lexicon.

In the historical Border Karelia, the Karelian dialects coexisted with the Eastern Finnish dialects for centuries, receiving ingredients from Finnish especially in the western parts of the area (Koivisto Reference Koivisto, Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018:60–61). A new layer of Finnish influence emerged after World War II, when Border Karelia and several other areas in Eastern Finland were ceded to the Soviet Union and their residents were evacuated and resettled in other parts of Finland; the speaker of the sample was one of them. It has been shown in a longitudinal study by Palander and Mäkisalo (Reference Palander and Mäkisalo2022) that even among the older generation, the Finnish influence increased after the Border Karelians had been resettled in new areas and lived among Finnish speakers.

5. Tver’ Karelians’ conceptions of their own dialect

In this section we examine how our respondents reacted to the sample representing the Tver’ Karelian dialect. We have treated our interviews as a set of qualitative data and the findings are based on qualitative analysis of these data. Section 5.1 deals with locating the sample and Section 5.2 reports findings related to the dialectal differences in Tver’ Oblast.

5.1 Locating the Tver’ Karelian sample

The respondents first listened to the sample representing their own variety; the speaker had lived in Tolmachi (in Likhoslavl’ raion). When they were asked where people speak in the same way as in the sample, the response was always similar: this kind of dialect is spoken in Tver’ Oblast, and it is very similar to the dialect of the respondents themselves. Many respondents named a specific raion, municipality, or village where the sample could have been recorded, but others used more vague expressions such as miän pagina ‘our speech’, miän kieli ‘our language’, or miän rukah ‘like us’, by which they could refer to the dialect spoken in their own village but also to Tver’ Karelian in general (see Vaattovaara (Reference Vaattovaara2009), concerning the concept of ‘our’ way of speaking in the context of the Far North in Finland). In the analysis we have carefully interpreted the pronouns ‘we’ and ‘our’ to point to the home village of the speaker only if the respondent stated that the sample is similar to their personal dialect or specifically referred to their village (even though they didn’t name the village). Otherwise, we have classified these answers in the group ‘Tver’ Oblast in general’. The results are presented in Table 2 and the places are marked in Figure 2 in Section 4.1. It should be noted that some respondents named more than one place: Stan1 gave three places and Stan3 and Klyuchevaya1 two places. These are all included in the table. A further note is related to Likhoslavl’, Maksatikha, Spirovo, and Rameshki: in these cases it was impossible to determine if the respondent referred to the raion in general or specifically the centre of the raion.

Table 2. The place names mentioned or implied after listening to the sample of Tolmachi dialect

Five respondents accurately recognised or guessed the place where the speaker had been living (Tolmachi); four of them lived in the same raion and one in the neighbouring raion. In Stan, a village situated near Tolmachi, five out of six respondents thought that the speaker was from their own village; the dialects of Tolmachi and Stan are probably similar because the distance between the places is only 20 km. Likhoslavl’ was suggested by three respondents who could have referred either to Likhoslavl’ raion or its centre. Zalazino and Anankino, both situated in the Likhoslavl’ raion, were mentioned once. All in all, 16 respondents located the sample in the right raion, and no one placed it outside Tver’ Oblast. The results are similar to Nupponen’s (Reference Nupponen2011:69) listening task where the respondents (speakers of the Savo dialect of Finnish) usually recognised their own variety very well. A further indication of the familiarity of the Tver’ Karelian sample was that many respondents suggested that it represents the dialect of their own village or a nearby village. The biggest distance between the home village and the suggested location for the sample was provided by Sel’tsy3 and Stan1, who thought that the sample might represent the dialect of Rameshki, spoken about 40 km from their places of residence (we have to note, however, that Stan1 also suggested the correct location, Tolmachi, and added that in Tolmachi people speak in a similar way as in Stan). No one mentioned the northern raions of Tver’ Oblast (Ves’egonsk, Krasnyy Kholm, and Sandovo) where a few Karelian speakers still live. It appears that our respondents have not had contact with these areas and are not familiar in their dialect; this is easy to understand because the distance between Tolmachi and Ves’egonsk is about 200 km and the traffic connections are poor. A similar observation of the lack of contact between the residents of the villages was provided by Joki and Torikka (Reference Joki and Torikka2001:466).

Interestingly, and somewhat surprisingly, six respondents out of 30 thought that they recognised the person who spoke in the sample, and some of them even named the person. Stan3 answered that the speaker was an old woman, living in Stan, who used to go to church. In the same way, Stan6 felt that the speaker was from Stan: the voice sounded familiar, but they didn’t know for sure who she was. The same was said by Mikshino2, who located the sample in their own village. Zalazino1 told us that they remember the person and her way of speaking but placed the sample in Anankino (example (3)). (The examples are presented using the same notation as in examples (1) and (2) in Section 4; grammatical glossing is not used because this article focuses on the content of the examples, not their linguistic features.) Eremeevka1 located the sample in Lindino and named the person (example (4)). Tolmachi2 also presented the name of a speaker who had lived in Tolmachi and was already deceased (example (5)). Possibly this phenomenon is due to the small size of Karelian communities: there are not very many Karelian speakers in the villages, and thus the respondents may be inclined to think that because the interviewee speaks Karelian she is probably known to them. None of these guesses were correct, but they indicate that the dialect used in the sample sounded very familiar, like the speech of their own linguistic community.

To conclude, our respondents recognised the old sample very well and all of them accurately stated that the sample represents the Tver’ Karelian variety. The results reported in this section are noteworthy when bearing in mind that the sample was recorded 60 years ago at a time when Karelian was still actively used in the villages. During the decades that followed, the use of Karelian has declined dramatically, and this in turn has affected the way the present speakers have acquired the language. Even though many of our respondents were not fluent speakers of Karelian and wanted to use Russian when sharing their answers, they still recognised the familiar dialect, which indicates latent knowledge of their heritage language. The only feature in the sample that may indicate a difference between the old and the present dialect is the word kuokka ‘hoe’ used in the sample: three respondents said they did not understand this word and one person mentioned that the word is not used any more. This, however, is understandable because working methods and tools have changed during recent decades. Overall, our findings are in line with earlier research among the descendants of Border Karelians in Finland, which showed that the respondents had good recollections of the Karelian they had heard during their childhood and reported having a rather good passive command of Karelian (Palander & Riionheimo Reference Palander, Riionheimo, Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018a, Reference Palander and Riionheimo2018b).

5.2 Observations on the dialectal differences in Tver’ Oblast

Our field trips were directed to the area which belongs to the biggest and most vital dialect of Tver’ Karelian, the Tolmachi dialect. At present, Tolmachi is the name of one of the central Karelian villages, situated in Likhoslavl’ raion; previously there was a Tolmachi raion, but due to the decentralisation policy of the Soviet Union it was divided and merged with its neighbouring raions (see Joki & Torikka Reference Joki and Torikka2001:465 and the references therein).

Recently, Novak (Reference Novak2019:229) has estimated that 95% of Tver’ Karelians speak the Tolmachi dialect. Karelian has been best preserved in the central areas of Tver’ Oblast, in the raions of Likhoslavl’, Spirovo, Rameshki, and Maksatikha (Novak Reference Novak2019). The Tolmachi dialect, however, is not uniform, but there are differences between villages. For example, a recent study, based on cluster analysis of the features reported in various grammatical descriptions of Karelian, implies the existence of seven subgroups of this dialect (Novak et al. Reference Novak, Penttonen, Ruuskanen and Siilin2019:414).

Even though we didn’t specifically ask for it, the listening task brought about several observations on the dialectal differences between the Karelian villages, based on the respondents’ earlier experiences. In this subsection we discuss their observations concerning general phonetic and prosodic properties, two specific linguistic features (the diphthong /ɨa/ and reflexive derivatives), and lexical differences.

5.2.1 General phonetic and prosodic features

A few respondents had paid attention to differences in pronunciation and phonetic features; they referred to these by using the term ‘accent’ or describing the phenomena in laymen’s terms. Klyuchevaya1 said that in Trestna (about 20 km away), people have an accent different from that in Klyuchevaya (for the villages, see Figure 2 in Section 4.1), and Klyuchevaya4 described the difference in intonation of the Trestna speakers by comparing it to singing:

Klyuchevaya2, in turn, had observed that in Kondushka and Danilkovo (6 km away from Trestna) Karelians speak a little differently and ‘distort’ some words; the respondent used the Russian verb коверкают. It is worth noticing that all the villages mentioned above belong to Maksatikha raion, and thus these respondents seem to be sensitive to fairly subtle differences in pronunciation.

In Stan, a village belonging to Likhoslavl’ raion, Stan5 told us that people in Tolmachi (situated in the same raion about 20 km away) speak in the same way as in Stan; the Karelians living ‘behind’ Tolmachi were reported to speak differently (Stan1) or in a ‘worse’ way (Stan1). The latter is an example of laymen’s metalanguage making a value judgement, a phenomenon that has been found in earlier studies as well (for the Finnish dialects, see Mielikäinen & Palander Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2014:107–111, 115–118). A further example of value judgment is a statement by Mikshino1 that in Zalazino people use ‘purer’ Karelian than in Mikshino, where the Karelian residents have largely shifted to using Russian. Both Zalazino and Mikshino are situated in Likhoslavl’ raion and the distance between them is only 20 km.

Another way to describe the pronunciation in subdialects was using Karelian and Russian adjectives meaning ‘soft’ and ‘hard’. This kind of difference had been observed both within a raion and between raions: Sel’tsy2 said that people in Spirovo raion speak in a softer way than in Maksatikha raion, where Sel’tsy is situated, and Sel’tsy3 thought that Karelian in Sel’tsy is softer than in Klyuchevaya, which belongs to the same raion. The word for ‘soft’ was thus used to depict the overall impression of the dialect, and in the same way, Livvi Karelians living in Russian Karelia have described their mother tongue (Karjalainen et al. Reference Karjalainen, Puura, Grünthal and Kovaleva2013:150). North (Viena) Karelians in Russian Karelia think that both their own Karelian variety and some other varieties of Karelian and Finnish are ‘soft’ (Kunnas Reference Kunnas2007:161, 312; Reference Kunnas, Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018:142). In Finland, people with Border Karelian roots consider Border Karelian ‘soft’, in contrast to Finnish (Palander Reference Palander2015:52). The impression of softness probably comprises a variety of linguistic features such as voiced plosives, hissing sibilants, palatalisation of consonants, or the overall Russian influence in Karelian phonetics (see also Section 6.2). Descriptions like these represent the category of detail proposed by Preston (Reference Preston1996), and because of the lack of linguistic details, they are global in nature.

5.2.2 The diphthong /ɨa/

A specific feature referred to by two respondents was the diphthong /ɨa/, which has been attested in some areas in Tver’ Oblast, also in some of the subdialects of the Tolmachi dialect (Bubrih, Beljakov & Punžina Reference Bubrih, Beljakov and Punžina1997: maps 4, 6, 15, 17, 19; Novak Reference Novak2019:234); elsewhere, the diphthong /ua/ or other variants are used. Zalazino1 (see example (7)) stated that people in Rameshki use the diphthong /ɨa/, and Stan2 suggested that in Zherekhovo people use the same diphthong in the Russian loanword [zɨʃara] ‘sugar’ (example (8)).

This diphthong is one of the Russian-induced features causing differences between the subdialects of Tver’ Karelian (Novak Reference Novak2019:234). It seems plausible to suggest that Tver’ Karelians’ ability to pay attention to and imitate this feature is based on their knowledge of Russian, their other native language; the back vowel /ɨ/ is part of the Russian vowel paradigm.

5.2.3 Reflexive derivation

Another feature pointed out was the use of specific morphological means in reflexive derivation. Sel’tsy3 said that in Sel’tsy people use a reflexive suffix different to that in Klyuchevaya, which belongs to the same raion (Maksatikha) and is situated about 35 km from Sel’tsy:

This observation probably reflects the wide variation of the South Karelian dialect, which forms the basis of Tver’ Karelian: according to Koivisto (Reference Koivisto1995:86), almost every parish of the South Karelian area (see Figure 1 in Section 1) has had their own way of forming reflexives. In Tver’ Oblast, the suffix containing the geminate affricate čč has largely replaced the other variants (Koivisto Reference Koivisto1995:88–89). However, the laymen’s observation (example (9) above) suggests that there still exists variation between the villages.

5.2.4 Lexical differences

Finally, several respondents reported observations of lexical differences; similarly, commenting on or imitating lexical phenomena has been common in studies of Karelian in Finland (Nupponen Reference Nupponen, Palander and Nupponen2005:163, 192; Palander Reference Palander2015:50–53) and in research concerning laymen’s observations of Finnish dialects (Palander Reference Palander2011:175–176). Eremeevka3 reported that in Likhoslavl’ raion the Karelians use the word paida ‘a man’s shirt’, whereas in Spirovo raion the word šoba is used (see example (10)). Also, Eremeevka4 commented on the word šoba, stating that their sister lives in the village of Biryuchevo (Spirovo raion), about 40 km away, and there paida refers to a man’s shirt whereas šobańe (a diminutive derivative of šoba) is a child’s shirt (see also KKS s.v. paita and sopaine).

Other lexical differences mentioned in the interviews were, for instance, t’uli and l’ökö ‘campfire’, hirvi and ṕedra ‘elk’, as well as sistraačikko and sizäričikko ‘sister’ (all of these were reported by Maksatikha4). These observations about different vocabulary are not surprising since lexical differences were also detected by researchers in the 1990s and early 2000s (Sarhimaa & Siilin Reference Sarhimaa and Siilin1994:268, Joki & Torikka Reference Joki and Torikka2001).

5.2.5 Overview of the observations

We can conclude that the Tver’ Karelians seem to be well aware of the differences between raions, i.e. administrative areas that are roughly comparable to provinces in other countries. However, our respondents had also perceived differences within raions, between municipalities or villages. To use Preston’s (Reference Preston1996) terminology, it seems that some of the respondents are aware of detailed phonetic and phonological differences and they were also able to imitate them, proving that they can control these features. Earlier research in Finland has shown that the smallest areal unit used by non-linguists when describing their observations is a parish or a municipality (Mielikäinen Reference Mielikäinen, Kaivapalu and Pruuli2006) and they rarely speak about differences between villages or between speakers in the same village. For Tver’ Karelians, even a distance shorter than 10 km can mean a difference in dialect, but more commonly they report differences with dialects spoken a few dozens of kilometres away. In the 1990s, the Tver’ Karelians interviewed by Sarhimaa and Siilin (Reference Sarhimaa and Siilin1994:268) even reported that they were not always able to understand the Karelian variety spoken in other villages. Our respondents did not bring up difficulties in understanding other Tver’ Karelian varieties, which may raise the question of whether the dialects have, during the last three decades, lost some of their differences, possibly due to the process of language endangerment.

The observations about the differences between the villages probably reflect the heterogeneous origin of the Tver’ Karelian variety. Most of the original settlers moved from Eastern Finland and from Border Karelia, and they were speakers of the South Karelian dialect; however, there were also settlers from the areas of the Livvi Karelian dialect (Saloheimo Reference Saloheimo2010, Sarhimaa & Siilin Reference Sarhimaa and Siilin1994:67−268, Joki & Torikka Reference Joki and Torikka2001, Koivisto Reference Koivisto, Riho Grünthal, Nuolijärvi and Riionheimo2022). Already in Border Karelia, the dialect had been diverse because Livvi Karelian was spoken in the eastern and southeastern parts. The migration to Tver’ Oblast may have resulted in a variety or a set of varieties that could be described as new dialects: originally, the speakers of South Karelian and Livvi Karelian lived in the same villages and their dialect varied significantly, but after a few generations, the differences largely levelled out and the dialects became more unified locally (Koivisto Reference Koivisto, Riho Grünthal, Nuolijärvi and Riionheimo2022:139−142). The current differences between the villages are probably traces from the original variation. However, another source for differences is the location of the villages in Tver’ Oblast: the villages lie in a relatively large area separate from each other and the roads have been in poor condition, making it hard to maintain contact between the villages. For example, Sel’tsy2 (living in Spirovo raion) said that they had never visited the neighbouring raion (Likhoslavl’) and thus they could not know how people speak there. The past and current linguistic situations of the Tver’ Karelians are a prime example of the well-known tendency that isolation preserves dialectal differences, whereas contact with other dialects decreases them.

6. Tver’ Karelians’ conceptions of Border Karelian dialect

The sample representing the Border Karelian variety was played to the respondents after we had discussed the Tver’ Karelian sample. In this section we report on the findings concerning the observations about this variety, which was rather unfamiliar to the respondents.

6.1 Locating the Border Karelian sample

The sample of the Border Karelian variety was recorded in Finland and differed considerably from the first one, and consequently there was much uncertainty in the respondents’ responses. Almost one-third of the respondents said that they do not know where people speak like this or left the place unmentioned (see Table 3). In most cases they understood the contents of the sample: they stated that most of the words are familiar to them and they were able to report the topics that the sample dealt with. The general impression was that these respondents were a little confused about the sample, which, at the same time, sounded both familiar and unfamiliar; however, they mostly observed that the sample did not represent the Tver’ Karelian variety. Interestingly, Klyuchevaya1 said that the language in the sample was ‘more Karelian’, by which they probably meant that the sample lacked the strong Russian influence that is present in the respondent’s own way of speaking Karelian.

Table 3. The place names mentioned or implied after listening to the sample of the Border Karelian dialect. A few respondents (Stan2, Stan5, Mikshino1, and Maksatikha1) named more than one place and these are all included in the table

Eleven respondents thought that the speaker had lived in the Republic of Karelia (in Russia), or specifically in Petrozavodsk or an area situated near Finland. These answers were often based on personal contacts with Karelians from the Republic of Karelia and depended on whether the respondent knew that Karelian is spoken outside Tver’ Oblast. For example, Stan1 had worked with Karelians who lived in Petrozavodsk, and Tolmachi2 had met some visitors from Petrozavodsk during the Kalitka festival in Tolmachi. In some cases the guesses were inaccurate in the sense that the respondent referred to a person who is not a native of the Republic of Karelia or to a Karelian variety that actually differs quite a lot from the sample. Zalazino1 and Zalazino2 supposed that the speaker is a Finn who had worked in Tver’. Eremeevka5 mentioned the villages of Vedlozero and Megrega, which are situated in Olonetskiy raion in the Republic of Karelia (where the Livvi Karelian variety is spoken); they had temporarily worked in collective farms in these villages during their student days.

Eight respondents said that the speaker in the sample lives in Finland and is either a Finnish Karelian or a Finn, although the distinction between these was not always explained. Klyuchevaya4 did not mention Finland as a place but said that they had seen a movie where Finns spoke in the same way as in the sample. Mikshino1 thought that the Finnish Karelians speak in this way, similar to the Estonians, and they also guessed that the speaker may be from a Baltic state. The comparison with Estonian is interesting, because in reality Estonian and Finnish differ quite a lot from each other on a phonetic level. Sel’tsy1 was sure that the speaker is a one-hundred per cent Finn, and said that the words were Finnish but that there also were a lot of Karelian words. Sel’tsy1 had lived in Finland for a short while and had learnt Finnish in language courses, and had thus had real contact with Finnish. They also stated that Karelian and Finnish are close to each other, and after listening to the sample for the second time they were able to list several Finnish words (or rather cognate words of Finnish and Karelian) that were present in the sample. Eremeevka2, in turn, had been acquainted with the Finnish language when a small group of religious Finnish men had visited the Tver’ villages a few years earlier, and Eremeevka2 thought that their accent was similar to the sample. Eremeevka1 justified their guess by referring to the content of the interview: in Tver’ Oblast, people preserve mushrooms in a different way to that described in the sample, and this is why the speaker must live in Finland.

An interesting finding was that even though the Border Karelian sample clearly differed from Tver’ Karelian, four respondents located the sample in Tver’ Oblast. Tolmachi was mentioned thrice, Likhoslavl’ twice, and Maksatikha once. These respondents had had some contact with the Karelians living in these villages, and when they were faced with the task we presented, they seemed to rely on these places they knew. It is unclear if they were aware of the fact that there are Karelians living in the Republic of Karelia and Finland. The places mentioned were situated in another raion or further away from the respondent’s own village. Similarly to the first sample, the remote Karelian dialect of Ves’egonsk was never mentioned and the respondents did not seem to know any Karelian speakers living there.

All in all, the Border Karelian sample was somewhat confusing for the respondents, and even though they could usually understand the content, the dialect clearly sounded different to them. Almost a third of them did not locate the sample anywhere, and four respondents implied that it may represent Tver’ Karelian. Two-thirds of the respondents placed the sample far away from Tver’, either in the Republic of Karelia or in Finland, the latter being the correct answer. The number of respondents who mentioned Finland was higher than we anticipated, and it seems likely that the answers were influenced by the fact that the respondents knew that the researchers were Finnish.

6.2 Observations on the dialectal features compared to Tver’ Karelian

After the respondents had heard both samples, we asked them to compare the samples and point out any differences. This subsection describes their observations on phonetic features in general and the variety of sibilants in particular as well as a few remarks on lexical differences.

6.2.1 General phonetic features

Six respondents commented on the phonetic differences between the samples: the Tver’ Karelian speaker did not (to their ears) have an ‘accent’ whereas the Border Karelian speaker had one:

In this case ‘accent’ probably refers to the Finnish-like intonation and differences in pronouncing plosives and sibilants (see also Section 6.2.3).

In linguistics, the term accent is used to refer to differences in pronunciation and to dialectal differences that are manifested in phonology, phonetics, or intonation (Chambers & Trudgill Reference Chambers and Trudgill1998:5, Llamas, Mullany & Stockwell Reference Llamas, Mullany and Stockwell2007:205). The term is also widely used by non-linguists. For example, laymen commonly describe the differences in pronunciation in the American English dialects by using this term (Niedzielski & Preston Reference Niedzielski and Preston2000:113), and the term is used by Finnish non-linguists as well, to refer to dialectal differences in pronunciation (Palander Reference Palander2011:29−30; Mielikäinen & Palander Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2014:121, Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2021 s.v. aksentti). Our findings are in line with the earlier research in that these respondents are sensitive to the phonetic differences in their native language. Interestingly, our respondents also used metalanguage similar to what has been found previously in Western Europe and the USA.

6.2.3 Sibilants

Eleven respondents paid attention to a specific phonetic feature: the quality of voiceless sibilant in the Border Karelian sample. In example (13), Maksatikha1 emphasises the difference between the sibilants by imitating the sharper s used in the Border Karelian sample and contrasting it with the hissing sibilant /ʃ/; another person, who was present during this interview, proposes the word pehmiimbi (‘softer’) to describe their own hissing sibilant and Maksatikha1 approves this characterisation.

The ways of describing the sibilant were not uniform, and Eremeevka2 said that the Tver’ Karelian /ʃ/ is more ‘rigid’ and the Border Karelian is, in contrast, ‘softer’:

In this example Eremeevka2 also used the word bukva ‘letter’ to refer the different phonemes. In a similar way, using the word for ‘letter’ to refer to sounds or phonemes is also very common in laymen’s metalanguage in Finland (Mielikäinen & Palander Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2014:133–134).

Imitating the different sibilants was a means used by several respondents (see also example (13) above). In example (14), Sel’tsy1 (who had lived in Finland for a while and thought that the speaker of the sample was a Finn) contrasts the hissing sibilant with the sharp sibilant of the Finnish language, and in example (15), they compare the Tver’ Karelian voiced sibilant /z/ to the voiceless one reportedly used in Finland. The ability to observe this kind of detailed differences and to imitate them is most probably based on the wide variety of sibilants in the phoneme systems of both Karelian and Russian, the native languages of the Tver’ Karelians.

Interesting observations and personal experiences were provided by Eremeevka5, who told us about the time when they studied in Petrozavodsk and during the summers worked in kolkhozes in Livvi Karelian villages. In Petrozavodsk, they were urged to speak Karelian, and the different sibilants provoked discussion:

Comments like these show that in addition to general susceptibility to the phonetic phenomena, the respondents’ own experiences have directed their attention to the sibilants: if someone has pointed out their way of speaking and even laughed at it, this linguistic feature will stay on their mind.

6.2.4 Lexical features

When we asked the respondents if they had understood the Border Karelian sample, they usually gave an affirmative answer, and when it was requested that they summarise the contents, they relayed the plot of the sample, i.e. salting mushrooms, in a largely accurate manner. The most difficult part were a few names of mushrooms that were different from Tver’ Karelian. For example, Maksatikha4 (who thought that the speaker is from Petrozavodsk) paid attention to the difference in meaning when using the words griba and sieni: in Tver’ Karelian, griba refers to mushrooms of the genus Boletus, which are fried or boiled, and sieni only refers to mushrooms that are preserved by salting. The speaker in the sample used the word sieni as a hypernym for both kinds of mushrooms, just like in the Finnish language. Stan2 said that they understood about 80% of the sample and that there were only a few unintelligible words such as voikkosii (which in reality was not used in the sample). The word gruušni (the genus Lactarius) elicited a few comments. Eremeevka1 and Kozlovo1 heard it in the form gruuždi, like in Russian, and Kozlovo2 mentioned that the word has been borrowed from Russian. Zalazino2, in turn, noticed the difference in pronunciation and that the speaker said gruušni. In addition to mushroom vocabulary, Sel’tsy1 pointed out the word laittaa ‘to make (food)’; this is a Finnish word and a Karelian would use the verb luad´ie.

6.2.5 Overview of the observations

The respondents’ observations about the differences between Border Karelian and Tver’ Karelian were mainly phonetic, apart from a few lexical remarks. Earlier research has shown that native speakers of a language easily perceive small differences in the pronunciation in the speech of learners of their language (see e.g. Moyer Reference Moyer2013), and the findings of our listening task are in line with these studies. A few respondents explicitly commented on the ‘accent’ of the Border Karelian sample on a general level, and roughly one-third of the 30 respondents specifically brought out the quality of sibilants. In Preston’s (Reference Preston1996) classification of folk linguistic observations, these perceptions of several sibilants belong to the level of availability: these features are available for the respondents, that is, they are aware of the variety of sibilants. In addition, most of their observations are accurate and detailed, and they were able to produce (i.e. control) these features (see Preston Reference Preston1996, Reference Preston and Brown2006:523–524).

These observations are very probably due to the Karelian–Russian bilingual background: the respondents seemed to be sensitive to small phonetic differences of sibilants in both of their languages. Russian and its predecessors have had a long-term influence on the phoneme system of Karelian, and present-day Karelian has roughly the same variety of sibilants as Russian (Sarhimaa Reference Sarhimaa, Bakró-Nagy, Laakso and Skribnik2022:275); consequently, Karelian speakers are able to perceive and imitate different sibilants. Similar findings have been reported in an earlier study in which North (Viena) Karelians recognised the hissing sibilant /ʃ/, which is also present in their own dialect, and they describe the use of this sibilant by way of the verbs äššättää or šöššötellä (Kunnas Reference Kunnas, Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018:144−145). However, the quality of sibilants was also a feature that Finnish students paid attention to in a test setting where they listened to a sample of Border Karelian, even though their native language only has one sibilant phoneme (Riionheimo & Palander Reference Riionheimo and Palander2017:231–232).

We end this section with a final note on metalanguage. Earlier folk linguistic studies have shown that non-linguists’ metalanguage is not uniform, but the same term may have different and even opposite meanings depending on the respondent (Preston Reference Preston, Jaworski, Coupland and Galasiński2004). In the present study, the adjective for ‘soft’ (in Karelian or in Russian) was mostly used to describe the use of /ʃ/, but three respondents (Tolmachi2, Eremeevka2, and Eremeevka3) thought that the sharp /s/ was ‘soft’. This demonstrates that the respondents perceived a phonetic difference but used varying terminology to describe it. Similar ambiguity in metalanguage was reported by Preston (Reference Preston, Jaworski, Coupland and Galasiński2004:81−83): in his study, the term nasal could refer to both nasal and non-nasal pronunciation, and despite the fluctuating terminology, his respondents were able to perceive the distinction between nasal and non-nasal sounds. In Finland and the Republic of Karelia, ‘softness’ is a quality assigned to the Karelian language, often in contrast to Finnish (Palander Reference Palander2015:52–53, Karjalainen et al. Reference Karjalainen, Puura, Grünthal and Kovaleva2013:150), but the same metalinguistic terminology is used by Finnish non-linguists to describe the differences between Finnish dialects (e.g., Mielikäinen & Palander Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2014:143, Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2021 s.v. pehmeä, pehmyt).

7. Concluding remarks

In this article we studied the perceptions that Tver’ Karelians have of dialectal differences in their heritage language. We had the twofold aim of examining how the respondents perceive the outcomes of diverse development in time (the sample of old Tver’ Karelian) and in both time and space (the sample of Border Karelian). The listening task revealed that while the respondents easily recognised their own dialect, the Border Karelian sample was harder to recognise and locate. They were, however, able to observe, report or imitate many phonetic features that made this sample different from their own Karelian variety. In this final section we discuss the findings in the light of the process of linguistic diversification and earlier folk linguistic research, and ponder the applicability of the listening task method in the Karelian context.

The Tver’ Karelian sample represented the variety that the older generation spoke 60 years ago; with this sample, we aimed to elicit observations about how this variety has changed in time during a few generations. So far, there is no thorough linguistic research that could give reliable information about how Tver’ Karelian has changed, but we do have a general overview of these changes, based on observations gained when compiling two corpora of Tver’ Karelian at the University of Eastern Finland. The Corpus of Tver Karelian 1957–1971 is based on old, archived interview material whereas The Corpus of Tver Karelian 2016–2019 consists of interviews made by our research group and represents contemporary language use. Our overall conception is that the Tver’ Karelian variety has become grammatically simplified and the Russian influence has become even stronger; both developments can be seen as symptoms of a progressive shift to the Russian language and endangerment of Karelian.

However, the listening task did not evoke observations about language change. The respondents recognised the Tver’ Karelian sample very well and all of them stated that the sample represents the Tver’ Karelian variety. A few respondents supposed that the speaker lived in another raion or at least several dozen kilometres away from their own village; on the basis of this, we can cautiously suggest that they may have noticed some difference between the sample and their own dialect but the difference was too subtle to describe. Because of the lack of comments concerning pronunciation (in contrast to the frequent comments on the Border Karelian sample), the results also imply that Russian influence was eminent already in the latter half of the twentieth century. The differences between the old sample and contemporary Tver’ Karelian do not seem to be so large that they would draw the attention of present Karelian speakers.

With the Border Karelian sample, we aimed at examining the consequences of diversification both in time and in space: Border Karelian in Finland and Tver’ Karelian have existed apart from each other for about 350 years, and despite their common origin they have been diverging from each other due to different language contact settings. Because of Finnish influence, the Border Karelian sample differed phonetically and (to a lesser extent) lexically from the Tver’ Karelian one. The sample was somewhat confusing for the respondents but two-thirds of them suggested that the speaker lives in either the Republic of Karelia (in Russia) or in Finland. Locating the sample varied a lot and it clearly depended on the respondents’ personal contacts with Karelians living outside Tver’ Oblast or with Finns. The isolation of Tver’ Karelian was also visible: some respondents did not seem to know that Karelian is also spoken in other parts of Russia and in Finland, and consequently they located the sample in Tver’ Oblast but further away from their own place of residence.

What was common, however, was a general feeling of unfamiliarity, which implies that the respondents were aware of linguistic features that differentiate Border Karelian and Tver’ Karelian. A long time span and geographical distance have given scope for linguistic divergence that is easily noticed and pointed out by the respondents. When pondering the specific differences between Tver’ Karelian and Border Karelian, the features most often mentioned were the overall ‘accent’ (referring to differences in phonetics and prosody) and the use of sibilants. The Tver’ Karelian hissing sibilant /ʃ/ was described as ‘soft’ and the sharper /s/ of the Border Karelian dialects was perceived as ‘hard’. The respondents were prone to pay attention to the phonetic differences, in addition to a few lexical differences. This may be explained by the fact that speakers are in general most readily aware of the use of different words and that they are able to detect even subtle differences in the pronunciation of their native language. Folk linguistic studies have shown that non-linguists do not usually comment on grammatical phenomena in this kind of test setting. However, the observations reported in this study may also reflect the nature of the divergence process: the dialects have been diverging mainly because of foreign influence in phonology and phonetics and in the lexicon, whereas the grammatical structure has remained more similar.

Finally, we end this article by evaluating our research method, which was originally designed to study laymen’s awareness of linguistic phenomena in the Western world and in majority language settings. In practice, applying the method proved to be challenging in the context of a small minority language in rural Russia. The situations where a larger group of Tver’ Karelians were gathered together in the village library, school, or club tended to become somewhat chaotic, and it was not always possible to have a quiet space for the interview and the listening task. A few of the older respondents had hearing difficulties when listening to the samples through headphones. The purpose of the listening task was not easy to grasp because the method was new to the respondents, and they were not used to speaking Karelian in this kind of situation. We also faced some language problems: the respondents did not always understand our way of speaking Karelian, and our skills in Russian were too limited to engage in mutually bilingual interaction. In some cases we had help in interpreting our questions into Russian, but this was not organised systematically. In hindsight, we suggest that when conducting this type of task in a multilingual setting, it would be beneficial to use interviewers who belong to the same community or at least have similar multilingual competence; the interviews could then last longer and give more detailed information. We have treated this study as a methodological experiment, and despite the difficulties, we feel that folk linguistic methods can and should be applied in the setting of minority languages – at least when the researchers anticipate possible difficulties and are ready to modify their methods.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lyudmila Gromova for organising our field trips to Tver’, and Viktoriya Gromova for acting as the interpreter in 2018; we also received interpretation assistance from Leena Joki, Ilia Moshnikov, and Tuomo Kondie. For translating the preliminary interview questions into South Karelian, we express our thanks to Katerina Paalamo. The Russian parts of the recorded interviews were translated into Karelian and Finnish by Natalia Giloeva. As we were writing this article, Milla Tynnyrinen translated the listening task samples into English. We are grateful for the three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions which helped us to greatly improve the article. The study was implemented in the project Migration and Linguistic Diversification: Karelian in Tver and Finland, funded by the Academy of Finland (project 314848).