Citizens of Ecuador have access to healthcare services in some regions of the country, but its quality varies widely. In neighboring Colombia, children have access to relatively better and more reliable health programs across the country, but in some regions, armed actors extract rents from the healthcare system as they challenge public order (Eaton Reference Eaton2006). Venezuelans have also faced the state’s inability to uphold public order, even though for a time in the 2000s, access to education was quite high throughout the country. Eaton notes that compared to Europe, “limited state capacity and highly incomplete processes of state formation have created a fertile landscape for the emergence of much more significant and destabilizing forms of territorial heterogeneity in Latin America” (2017, 6). We define territorial heterogeneity as subnational variation across territorial units in the provision of goods and protection of rights by states. O’Donnell (Reference O’Donnell1999) identified substantial territorial heterogeneity across the region and highlighted how uneven rights protections by the state will necessarily shape the nature of democracy.

The articles in this special issue contribute to a vibrant field that addresses these core issues of state presence and regime type and how they vary subnationally (e.g., Behrend and Whitehead Reference Behrend and Whitehead2016; Ch et al. Reference Ch, Jacob, Steele and Juan2018; Enriquez et al. Reference Enriquez and Sybblis2017; Giraudy and Luna 2017; Harbers Reference Harbers2015; Snyder Reference Snyder2001). The articles analyze how the provision of public goods and protection of rights vary across territory within countries. This focus on territorial heterogeneity contrasts with other forms of within-country heterogeneity in access and distribution, such as socioeconomic inequality or variation across ethnic and racial groups (see also Otero-Bahamón 2019; Rogers Reference Rogers2020). In this introduction, we propose a conceptual framework to characterize territorial heterogeneity across states and over time, based on the contributions to the special issue. In this way, we provide the foundation for a new research agenda to compare forms of subnational variation across states.

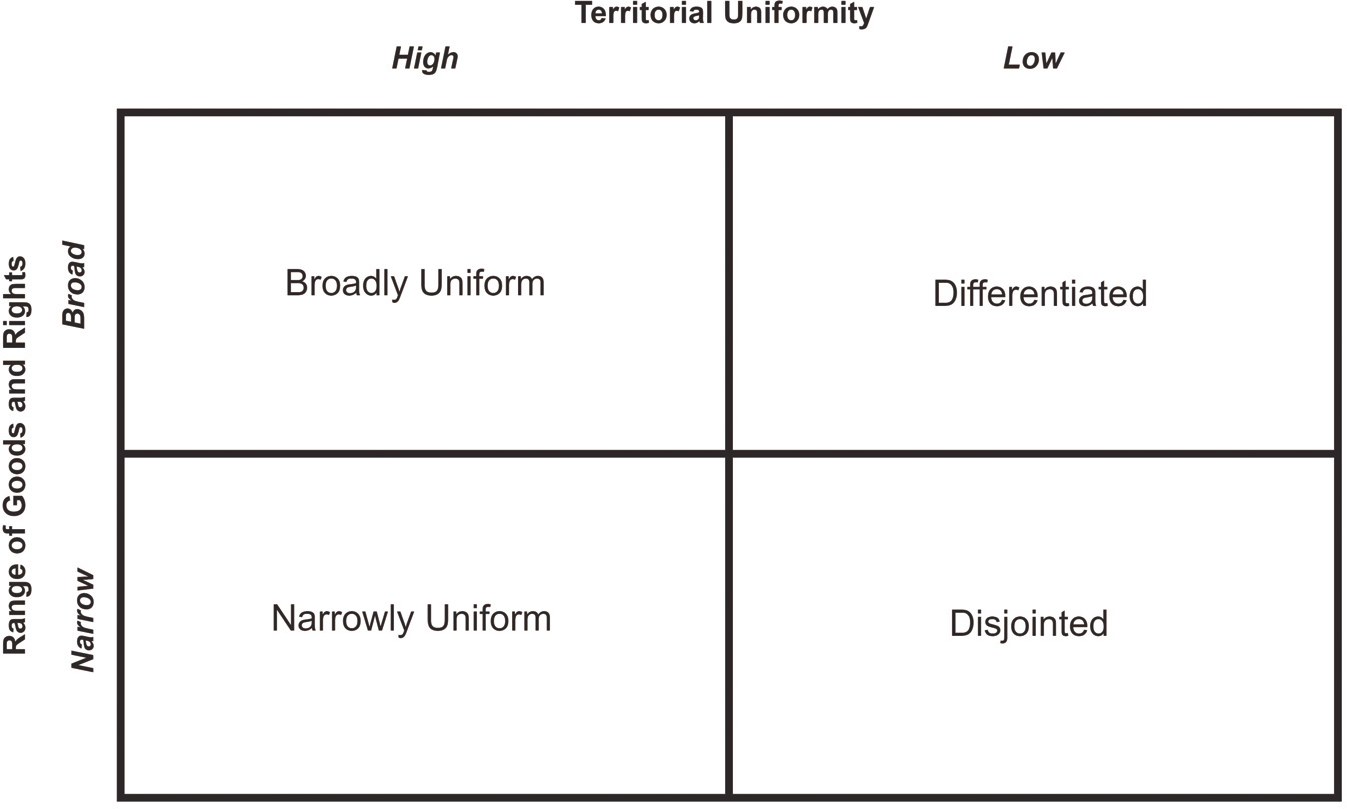

Our typology consists of two dimensions: the range of publicly provided goods and guaranteed rights, and their uniformity across the territory. The dimensions of the typology delineate four types of states: broadly uniform, differentiated, narrowly uniform, and disjointed. Broadly uniform and narrowly uniform states both offer some public goods and rights throughout their territories, but the range is more comprehensive in the former than the latter. Narrowly uniform states often prioritize a particular good and try to extend it throughout their territory. Differentiated states offer broad public goods, but only in certain parts of a state’s territory, such as the capital and regional cities. Disjointed states do not offer a consistent set of public goods and rights, resulting in a patchwork of sparsely provided goods. The differences among the types of states in our framework are substantively important and reveal different forms of deviation from the Weberian ideal of territorial homogeneity.

We use our typology to illustrate what the special issue articles collectively contribute to our understanding of territorial heterogeneity across states and to identify the new questions they raise. Two recurring themes in this issue are attempts by states to create more uniformity throughout their national territory, and increased uniformity after policy reforms, even when heterogeneity was the goal. The articles show that while many public goods and rights are uneven throughout particular states’ territories, some goods and rights have become more uniform over time (e.g., healthcare in Brazil, women’s political rights in Mexico), while others remain stubbornly uneven (e.g., property rights in Colombia). Taken together, the articles prompt questions, such as what explains movement toward uniformity across sectors and states? Is unevenness more likely to persist in some sectors than others, and if so, why? Under what conditions do nationwide policy reforms increase territorial heterogeneity?

This introduction offers a brief discussion of the core concepts of the special issue, followed by a short overview of the articles. Against this background, we develop our typology and explain how the articles contribute empirical and theoretical insights in their own right and how they jointly push forward our understanding of subnational variation across states. Subsequently, we place this in the context of the literature on states and state building in Latin America, and we identify promising areas for future research.

How Should we Conceptualize Territorial Heterogeneity?

This special issue is concerned with how the state varies subnationally. Prominent conceptualizations of the state imply that strong states provide public goods, especially order and protection, throughout their territory (e.g., Weber Reference Weber1947; Tilly Reference Stepan1985). This understanding informs Mann’s influential definition of infrastructural power as “the capacity of the state actually to penetrate civil society, and to implement logistically political decisions throughout the realm” (Reference Mann1988, 5). In contrast, we take state presence as variable throughout the realm, and focus on the heterogeneous provision of goods and protection of rights. We argue that there are different forms of such territorial heterogeneity, and that grouping them together under the banner of overall weakness undermines our ability to understand them. This is particularly true in Latin America and across the developing world, where few states meet the ideal of broad and territorially uniform public goods provision. Even strong states— those with “sufficient resources for the maintenance of an effective bureaucratic and administrative state” (Steinberg Reference Staniland2017, 225)—do not deploy these resources evenly across their territory. Furthermore, even if resources are invested equitably, outcomes across territory may differ. This heterogeneity is substantively important.

Because scholars of the state have tended to think of strength and homogeneity as closely related, heterogeneity—much like state weakness—has often had an implicitly negative connotation in the literature on state building. In civil war studies, the state’s limited presence in peripheral areas has been associated with the onset of civil war—even though, by most definitions, a civil war would indicate a weak state (Kocher Reference Kocher2010). Indeed, we may observe civil war because relatively stronger states choose to fight challengers rather than ignore them. More recent work on subnational conflict points out that a host of possible arrangements between state and nonstate actors—both armed and unarmed—are compatible with modern states (Staniland Reference Staniland2017; Post et al. Reference Post, Bronsoler and Salman2017).

The literature on decentralization and comparative territorial politics has also recognized the potential benefits of heterogeneity in governance. Federalism makes it possible to accommodate distinct linguistic or cultural communities within a country (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2016). This offers a strategy for “holding together” countries that might otherwise dissolve into territorial conflict (Stepan Reference Steinberg1999). Arranging governance so that subnational units play an important role formally recognizes that preferences for public goods provision may vary and that in certain situations, territorial heterogeneity may be preferable to the coercive enforcement of uniformity (see also Staniland Reference Staniland2012).

Territorial heterogeneity also has implications for rights protections. O’Donnell’s key concern (1999) was whether heterogeneous states would be able to enforce the equal citizenship required for democracy. An important body of scholarship on the territorial dimension of democratization has since demonstrated that Latin American states vary not only in how effective state institutions are throughout the territory, but also in how consistently citizens’ political, civil, and social rights are enforced across subnational units (e.g., Cornelius Reference Cornelius1999; Gervasoni Reference Gervasoni2010; Gibson Reference Gibson2013; Giraudy Reference Giraudy2015).

The articles in this special issue focus both on rights protections and public goods provision across subnational jurisdictions (Giraudy et al. Reference Giraudy, Moncada, Snyder and Giraudy2019). Rights and goods vary within states’ territories at different scales, such as municipalities (Sánchez-Talanquer, Otero-Bahamón, and Cleary this issue), provinces (Paredes and Došek), and states (Giraudy and Pribble). Throughout this introduction, we refer to them collectively as regions, because the term broadly captures a subnational point of potential variation. Which territorial scale or level of analysis is appropriate probably depends on the outcome of interest and on the proposed theoretical mechanism (Soifer Reference Soifer2019).

Subnational Variation Across States in Latin Merica: An Overview of the Special Issue

The articles in this special issue cover five countries in Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. The analyses focus on a range of policy sectors and document within-country variation in core state activities, such as the provision of public health services and the protection of property rights. They also demonstrate territorial heterogeneity in the guarantee of individual and collective rights, focusing specifically on women and indigenous citizens.

The article by Jenny Pribble and Agustina Giraudy focuses on health outcomes in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico and asks under which conditions countries move toward uniformity in outcomes. While territorial inequality in health outcomes declined substantially in Brazil, Mexico saw only a moderate decline and little change, followed by a limited decline in Argentina in the aftermath of decentralization. Two factors account for this divergence in trajectories, Giraudy and Pribble argue. First, if the decentralization push comes from national technocrats rather than from bottom-up pressure by nonstate actors, health outcomes are less likely to become more equitable over time. Second, the strength of coordination and oversight mechanisms by the central government also plays an important role in reducing territorial variation in outcomes.

Silvia Otero-Bahamón also examines how and why key healthcare outcomes— specifically, infant and maternal mortality—vary across Colombian municipalities. Her analysis shows that the national policy framework in the sector and whether the policy is “place-sensitive” shape the well-being of local populations. A one-size-fitsall or “place-blind” approach to policy is likely to compound subnational differences. Her analysis highlights that reducing territorial heterogeneity requires the state to design and implement tailored policies to achieve similar outcomes in different local circumstances.

Mariano Sánchez-Talanquer also highlights territorial unevenness in Colombia, but his analysis focuses on fiscal capacity and the quality of cadasters. Where conventional theories of state building would expect the quality of both of these aspects of state activity to covary because the legibility of assets facilitates taxation (Scott Reference Scott2009), his article shows that the opposite pattern emerges. He demonstrates that while property holders sought to have their property claims recognized and registered in cadastral records, they evaded taxation by manipulating the assessment process to systematically undervalue the land. In doing so, they created the unevenness in property rights and extraction that continues to characterize the Colombian state.

Whereas Sánchez-Talanquer highlights how unevenness can be an unintended consequence of state-building projects, the article by Matthew Cleary shows how efforts to preserve local autonomy can actually result in increasing uniformity. The formal recognition of autonomy in communities that already enjoyed substantial de facto control over local governance created a legal mechanism through which the constitutionality of local practices could be challenged. Cleary examines how this played out with regard to women’s political rights, as the principle of gender equality established in the national legal framework created a contested issue in communities that had long restricted women’s participation in public life.

The territorial unevenness of political inclusion and indigenous representation is also demonstrated in the article by Maritza Paredes and Tomáš Došek on Peru. While the context was not favorable for ethnic parties at the national level, outcomes at the subnational level varied. These authors’ analysis—based on extensive fieldwork—identifies cohesive indigenous organizations and political capital as necessary and jointly sufficient for the substantive representation of indigenous interests in the political arena. Crucially, though, their findings highlight that descriptive and substantive representation do not go hand-in-hand in the subnational cases they study. The extent to which indigenous citizens are included in the political system—either descriptively or substantively—thus varies territorially.

The contribution by Kent Eaton takes variation across subnational units as a given and outlines the methodological challenges inherent in studying territorial heterogeneity. Instead of conceptualizing subnational units as independent, he argues, scholars need to consider carefully whether and how variables located outside the unit influence local outcomes. He distinguishes between vertical influences, which come from the national level or the international level, and horizontal influences, which arise through the interaction between subnational units at the same level. The articles by Otero-Bahamón and Cleary in this issue constitute examples of theorizing vertical relationships. Otero-Bahamón studies the role of the national policy framework in explaining subnational variation in basic health outcomes, and Cleary points to the role of new laws provoking local changes in political representation.

Each of these articles contributes new data on subnational variation and new theories on its causes and consequences. Here, we draw on these insights to characterize states based on their territorial heterogeneity. This exercise allows us to generate new questions about state building based on the special issue articles and to highlight how the articles contribute to establishing a new research agenda.

A Typology of Territorial Heterogeneity

The articles in the special issue all illuminate aspects of O’Donnell’s Reference O’Donnell1999 conceptual map, on which distinct zones indicate varying performance of state institutions and the rule of law. He notes that democratic states in Latin America claim to establish and guarantee social order throughout their national territory. Empirically, though, the extent to which states actually provide order and guarantee rights varies widely across the territory. How can we characterize and study this heterogeneity? How can we draw on the wealth of evidence about subnational variation to “scale up” to the national level (Giraudy and Pribble Reference Giraudy and Pribble2019)?

We present a new typology of states to address these questions. We conceive of states as differentiated sets of institutions that uphold citizens’ rights and provide public goods to the population of a specific territory, over which they have de jure authority (see also Mann Reference Mann1988). We focus on contemporary states, which differ from their historical antecedents in the range of public goods they provide to citizens and in the range of citizen rights they formally recognize (Skocpol and Amenta Reference Skocpol and Amenta1986; Poggi Reference Poggi1990; Desai Reference Desai2003).Footnote 1

Our typology identifies variation in two dimensions: the range of goods and rights provided by the state and the territorial uniformity of their provision. These goods, as illustrated by the articles in this special issue, include health, security, education, and infrastructure, as well as the rule of law and a clean environment.Footnote 2 The rights we refer to guarantee equality before the law, as well as participation in the political system and equal participation in society more broadly. Based on our two dimensions, figure 1 distinguishes four types of states.

Figure 1. Conceptual Typology of States

The first dimension refers to the range of public goods provided and rights protected by the state. By range, we mean “how many” or “comprehensiveness,” and the typology is agnostic as to which specific goods or rights a state provides in a particular place. Previous scholarship has sometimes viewed this range as a logical hierarchy, in which states initially focus on minimal functions (law and order, property rights, public health), then expand to intermediate functions (basic education, environmental protection), and finally graduate to activist functions like fostering markets (see, e.g., World Bank Reference Weber and Parsons1997). Our typology presupposes no such hierarchy. Across Latin America and the developing world, states have invested in the provision of goods, such as pensions or health insurance, despite severe shortcomings with regard to functions like public health and order (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Iyer and Somanathan2008, 3119; Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2004, 2013). Moreover, as the article by Sánchez-Talanquer in this issue highlights, even fundamental aspects of state building like property rights and taxation do not necessarily go together. Empirically, certain combinations probably occur more regularly than others, but we leave this as an open question.

The second dimension captures the degree of territorial uniformity in goods provided and rights protected. Though some places in a state may have comprehensive public goods and rights, this breadth of provision is often uneven throughout the territory. Goods and rights may be delivered in a variety of forms. As the contributions to the special issue highlight, the provision of goods and services often involves governments at different levels (e.g., Giraudy and Pribble; Otero-Bahamón). For our classification, it does not matter whether they are provided by the central government, by regional or local governments, or through the cooperation of different levels of government. What matters, instead, is whether any part of the state provides these goods, either directly or by closely regulating and monitoring private providers so that they are available in a given region (see Harbers Reference Harbers2015; Post et al. Reference Post, Bronsoler and Salman2017). This multilevel view of the state is informed by the literature on decentralization and multilevel governance (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Gary Marks and Schakel2016; Niedzwiecki et al. Reference Niedzwiecki, Osterkatz, Hooghe and Marks2018).

Jointly, these two dimensions can be illustrated by a 2×2 table that allows us to classify territorial heterogeneity in public goods provision and rights protections. Of the four quadrants, only the first is homogenous. The other three are characterized by significant heterogeneity, albeit of different types. States can shift from one type to another over time. Differentiated or disjointed states can become narrowly uniform states following a concentrated policy push (e.g., Otero-Bahamón; Giraudy and Pribble) or due to the unintended consequences of a reform (e.g., Cleary). Moreover, states can become disjointed if public goods provision breaks down. The current crisis in Venezuela forcefully illustrates this point. The typology allows us to put the articles in this issue in dialogue with one another, and to raise new research questions.

The Broadly Uniform State

The broadly uniform state has long served as the implicit model of an ideal-typical “strong state” for the state-building and state capacity literature (Mann Reference Mann1988). Nevertheless, its incidence is geographically and temporally limited. This type of state provides a comprehensive range of public goods to citizens throughout the territory. The quintessential examples are Nordic welfare states that provide a broad range of public goods and uniformly guarantee the rights of their citizens. The central government plays an active role in coordinating and financing public goods, even though subnational governments are often in charge of implementation and monitoring (Sellers and Lidström Reference Sellers and Lidström2007; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1970). Across Latin America, empirical examples of similar states are scarce. O’Donnell (Reference O’Donnell1999, 138), focusing especially on the territorial dimension of the rule of law, identifies Costa Rica, Chile, and Uruguay as examples of “relatively high homogeneity.”

The Differentiated State

The differentiated state also provides a broad range of public goods, but has large territorial differences in the location and types of goods provided and rights protected. As a result, the way the state shapes citizens’ lives in different regions of the country differs substantially. Differentiated states may vary from a wide range of public goods in some areas and very few in other regions to relatively plentiful goods in many areas with diverse constellations of those goods across the country.

Three countries that demonstrate the range of differentiated states in the Americas are Colombia, Brazil, and Peru. In Colombia, before its 1991 Constitution and subsequent decentralization efforts, some regions of the country offered a wide range of public goods, particularly in regional cities, while others remained virtually untouched by the government (Soifer Reference Soifer2016). The articles on Colombia by OteroBahamón and Sánchez-Talanquer illustrate subnational inequality in public goods provision in crucial policy sectors. Similarly, contemporary Peru provides fairly comprehensive public goods in the capital, while it formally delegates responsibility for public goods provision in large concessions to nonprofit organizations and corporations in the Amazon (Eaton 2015).

Contrary to the broadly uniform state, where one national vision is enforced across distinct subnational units, public goods “baskets” in the differentiated state could potentially be tailored toward local needs or preferences, as suggested in the fiscal federalism literature (Oates Reference Oates2005; Reference RogersRogers 2020). Yet as the contribution by Paredes and Došek on Peru demonstrates, the extent to which different groups can influence the policy process and exercise their political rights varies across subnational units. Moreover, the political process in subnational units is not necessarily democratic. The article by Sánchez-Talanquer on property rights and taxation in Colombia demonstrates that the preferences of subnational elites often play an outsized role in determining the local basket of goods that the state provides. They push for the goods and services they find most appealing and—if the provision of resources from the central government is limited—for which they are willing to shoulder the tax burden (see also Faust and Harbers Reference Faust and Harbers2012; Soifer Reference Soifer2016). As a result, subnational public goods baskets may not necessarily be aligned with the preferences of local citizens, and how much different groups influence what goods the state prioritizes is a separate, important question.

The Narrowly Uniform State

The narrowly uniform state prioritizes a limited range of public goods and provides them uniformly throughout the territory. The provision of these goods extends even to marginalized areas. Across Latin American states, there is significant cross-country variation in how consistently the state pushes the expansion of certain goods throughout its territory and whether it is successful in doing so. In this issue, Giraudy and Pribble and Otero-Bahamón focus on the role of healthcare expansion across Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia. The authors find that over time, inequalities in health outcomes within the countries declined. However, each country followed different paths to increasing uniformity of outcomes. The articles highlight the importance of coordination and cooperation across levels of government for successful public goods delivery.

The specific sector that states prioritize for uniformity probably varies over time. Mid-twentieth-century corporatism could be conceptualized as a state project of narrow uniformity. During the heyday of the “corporatist citizenship regime,” states sought to expand their societal and territorial reach by investing in organizations that provided land to rural populations and access to agricultural subsidies. Yashar’s 1999 analysis highlights the shift from one imperfect attempt at narrow uniformity to another. As the result of neoliberal influences, states rolled back the distribution of benefits through corporatist organizations and pushed a uniform legal order with individual property rights instead. The article by Matthew Cleary in this issue shows how this new project challenged indigenous autonomy in Mexico.

Beyond the priority public goods, local public goods provision varies in narrowly uniform states. In some regions, it may be on a par with regions in the differentiated state, whereas in others there is little state provision beyond the priority goods. Overall, the narrowly uniform state is characterized by significant heterogeneity with regard to nonpriority goods.

The Disjointed State

In the disjointed state, public goods are not provided in a systematic or territorially uniform manner. Resources devoted to public goods provision vary territorially, as there is no nationwide strategy to compensate for regional disparities. The state may provide some goods in some regions, but compared to the other three types, public goods provision is more limited in terms of range and territorial reach. The result is a patchwork of sparsely provided goods. In such states, nonstate actors, like insurgent groups, churches, and NGOs, may provide goods locally. Though they may coordinate with state institutions, they are just as likely to operate independently (Post et al. Reference Post, Bronsoler and Salman2017). Some regions may not experience any regular provision of public goods.

The clearest example of a disjointed state in Latin America is Venezuela in recent years. The humanitarian crisis has exposed the state’s withdrawal from the provision of basic supplies to its population, including medicine and healthcare, beyond Caracas. Armed groups are stepping in to fill gaps in some regions, even in the absence of a civil war (Kurmanaev Reference Kurmanaev2020). Venezuela’s experience, moving from one of the more robust differentiated states in the region (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1999; Soifer Reference Soifer2016) to perhaps the most disjointed, is a stark illustration of how states can shift over time. Other instances of states that do not consistently provide basic goods and rights throughout the territory are Honduras and El Salvador.

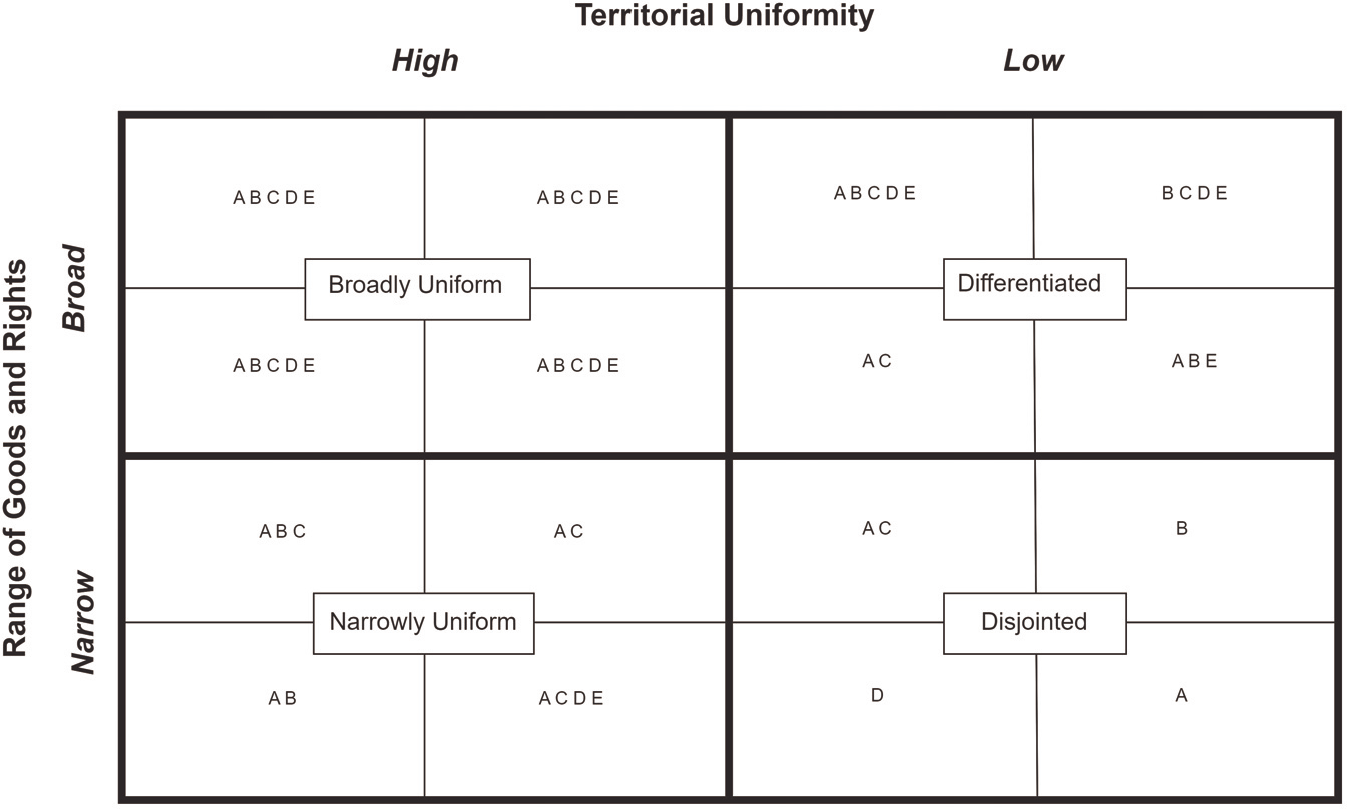

To illustrate the types of states delineated by our typology, figure 2 displays the distribution of five public goods and rights (A, B, C, D, E) across four regions that make up a hypothetical state. In the broadly uniform state, the full range of goods is available in all regions. In the differentiated state, only the top-left region has the full basket, and despite the overall broad range of goods, the number of goods per region varies. In the narrowly uniform state, by contrast, good A is available in all regions, even as the range of state-provided goods varies. In the disjointed state, the range of goods is limited, and no good is available consistently.

Figure 2. Public Goods Across Regions by Type of State

Note that the differentiated, narrowly uniform, and disjointed state each contain a region in which the state provides goods A and C, but that each of these regions is embedded in a different national context. The two dimensions of the typology thereby allow us to identify relevant variation across countries. Our typology provides flexibility to scale back up to the national level by asking how the state fulfills its core activities throughout the territory (see also Giraudy and Pribble Reference Giraudy and Pribble2019 on scaling up).Footnote 3 The typology avoids a normative commitment to what the state should do or look like. Focusing on what the state does within its borders allows us to conceptualize variation across states in a new way. Furthermore, the variation it highlights, illustrated empirically by the contributions to the special issue, often defies expectations derived from the literature on state building in Europe, such as the notion of an orderly sequence of public goods expansion and that of states steadily moving toward territorial homogeneity (Weber Reference Weber1947; Marshall Reference Marshall1965; Tilly Reference Stepan1985).

Research Agenda: What Explains Heterogeneity or Uniformity?

The articles in this issue point to and suggest answers for new and important questions. Under which conditions do policies intending to produce uniformity succeed, and when do they fall short? When do policies to preserve subnational autonomy and heterogeneity backfire and lead to greater uniformity instead? And when do state-building efforts that aim to create uniformity result in heterogeneity? Who are the key actors driving uniformity or resisting it? What are the structural factors that contribute to the state types? How do goods and rights covary within states? Is there a sequence of public goods provision that is more likely to lend itself to broader uniformity? What is the relationship between types of territorial heterogeneity and democratic governance?

The articles in this issue highlight the need to distinguish between uniformity as an intended policy goal and as the actual outcome of reforms. Giraudy and Pribble, for instance, study cases in which decentralization reforms were associated with more uniform outcomes in the health sector. They find that the bottom-up nature of the reform coalition in Brazil, which included a social movement actively promoting the expansion of health care, was associated with more uniformity than the top-down nature of reforms in Argentina and Mexico.

In Colombia, it was not until place-sensitive approaches were adopted that outcomes became more uniform across regions (Otero-Bahamón). Policies that are place-blind and do not consider variations in local circumstances are likely to compound preexisting inequalities between units. In Mexico, Cleary reveals a contrasting relationship between the intention of reforms and the actual outcome. He demonstrates the increased uniformity of women’s political rights in spite of policies explicitly intended to preserve difference across subnational units. In contrast, measures to protect indigenous political representation in Peru did not lead to uniformity, as Paredes and Došek show. What explains which types of policies retain subnational variation, or in which contexts variation is preserved? The articles in this issue answer these questions by revealing the role of new actors, in addition to structural and geographic conditions.

So far, the literature on state building has emphasized the role of elites, especially at the subnational level, in promoting or impeding state formation (Boone Reference Boone2012). In explaining the lack of territorial homogeneity across Latin American states, this literature shows how subnational powerholders resisted efforts to strengthen central authority after independence (Centeno Reference Centeno2002; Centeno and Ferraro 2013; Kurtz Reference Kurtz2013; Soifer Reference Soifer2015). The interests and preferences of subnational elites then played an outsized role in shaping public goods provision, often resulting in a patchwork of goods that persists to the present (e.g., Dell Reference Dell2010; Garfias 2018). Adding to the work on historical legacies of state formation, the new contemporary actors identified here include social movements (Giraudy and Pribble), technocrats (Otero-Bahamón; Giraudy and Pribble), courts (Cleary), political parties (Paredes and Došek), and international actors, such as NGOs or development organizations (Eaton), unwittingly or not.

For the case of Mexico and the unintended expansion of women’s political rights, Cleary identifies the courts as decisive actors, prioritizing uniform constitutional rights for individuals over protections for indigenous autonomy. For Paredes and Došek, no such court oversight guarantees the forms of representation for any given community in Peru. Instead, political parties determine the extent of substantive indigenous representation across communities. In Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil, Giraudy and Pribble point to the importance of distinct reform coalitions for achieving uniform outcomes across regions. Eaton, in turn, demonstrates the need to think through how international actors may influence national and subnational outcomes. Collectively, the articles find that a broad variety of actors influence the extent of uniformity that states achieve in a given policy area or sector. An important line of inquiry for future research on the role of actors in contemporary processes of state building is to explore which actors are relevant and influential across sectors and under what conditions they are able to achieve their goals.

Identifying the relevant actors for particular outcomes is also a key way to avoid the sort of methodological pitfalls that Eaton identifies. Are threats to subnational unit independence likely to come from horizontal relationships among the units, such as those that may be fostered when a social movement is active in multiple regions of a country? Or does the embeddedness of subnational units in vertical relationships, and their interaction with institutions, such as courts or parties, influence outcomes within units? Answering these questions should guide scholars in their approach to subnational analysis. Importantly, as this collection of articles illustrates, the answers to these questions are likely to vary across the set of public goods or rights that the state is theoretically responsible for providing or protecting.

In addition to highlighting the role of actors, the articles in this special issue speak to the continued importance of geographic and demographic factors that have historically worked against state penetration in Latin America (e.g., Centeno and Ferraro 2013). In this literature, rugged terrain, low population density, and distance from the capital have been identified as structural conditions that rendered the provision of public goods in peripheries prohibitively expensive for states with limited resources (Herbst 2000; Pierskalla et al. Reference Pierskalla, Schultz and Wibbels2017). Against this historical backdrop, one question that emerges is whether technological advances in communication and transportation could provide ways for a contemporary state to become more uniform. Otero-Bahamón’s article in this issue highlights the continuing importance of structural variables, such as population density and geography, despite advances in technology. She argues that ignoring such structural differences is likely to compound subnational variation. Relevant questions for future research are which conditions lead states to design and implement place-sensitive policies, and when do those policies specifically address territorial heterogeneity. The articles in this issue, especially the contributions by Otero-Bahamón and Giraudy and Pribble, show that contemporary states sometimes develop policies to promote uniformity even in seemingly adverse circumstances.

Beyond the determinants of uniformity in specific policy sectors, the contributions also raise questions about the relationship between types of subnational variation across different types of public goods or sets of rights. While Colombia made strides to increase equitable health outcomes across regions, the state’s attempts to provide more uniform property rights and to improve the quality of cadasters were consistently undermined (Sánchez-Talanquer this issue). The state’s ability to tax effectively therefore remains stubbornly uneven across municipalities, even as it has been able to achieve more uniformity in the field of public health. The contrast between Otero-Bahamón’s and Sánchez-Talanquer’s findings shows that states can achieve greater uniformity in some sectors, even while failing to do so in others. What explains this divergence across sectors?

The literature on state building suggests two sets of explanations for variation across sectors that merit further research. First, achieving uniformity may be more challenging in some sectors than in others, primarily on the basis of how complex the provision of a certain good is (e.g., Dargent 2015). When the provision of a good is fairly straightforward, uniform provision may be possible even when local circumstances vary. The article by Sánchez-Talanquer suggests, however, that the difficulty of registering property versus assessing its value does not satisfactorily explain why differences across these two areas of state activity persist. This puzzle points to the need to explicitly consider variation in state strategies (Geddes Reference Geddes1996) and in which goods and rights are prioritized in a given time period.

The literature on state building also shows that state builders see certain types of goods as more important than others. For instance, state expansion in Europe in the late nineteenth century tended to emphasize educational reforms (Anderson Reference Anderson1991; Weber Reference Vaughan1976). Vaughan’s Reference Tilly, Peter, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1997 work on postrevolutionary Mexico also illustrates the importance central elites assigned to public education as a key ingredient in forging a modern nation. Between 1923 and 1936, the number of teachers in rural areas grew from 690 to 16,079 (Vaughan Reference Tilly, Peter, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1997, 12), and the provision of education explicitly included marginalized areas (see also Soifer Reference Soifer2013 on education in Peru). A key question for further research is how a particular type of public good is selected for uniform provision.

Another question that emerges from this divergence across sectors is whether the prioritization of certain goods and rights influences the success of state-building projects. Are they more likely to persist if certain types of goods (e.g., public education in a national language, a nationwide infrastructure network) are prioritized early on (Darden and Mylonas Reference Darden and Mylonas2015; Soifer Reference Soifer2016)?

Furthermore, the articles in this special issue also raise doubts about the assumption of a hierarchy of goods provision. Latin American countries have the highest rates of lethal violence in the world. Nevertheless, the articles in this issue show that Mexico and Colombia—with extreme levels of lethal violence and the longest-running insurgency, respectively—have made significant strides in improving uniformity in health outcomes across their territories. This is consistent with findings in the civil war literature, which has shown that armed groups often operate alongside state institutions at the local level (Mampilly Reference Mampilly2011; Arjona Reference Arjona2014; Harbers et al. 2016; Ch et al. Reference Ch, Jacob, Steele and Juan2018). Some states are able to provide a broad set of public goods across their territory, even as they are unable to achieve uniformity in protecting their citizens from violence.

Crucial questions moving forward are why and under what conditions states invest in expanding the provision of goods and rights, even when order has not been established. A related line of inquiry is when and where the lack of public order undermines the provision of other public goods. More generally, how sectors covary within a state can also differ quite a bit across states, and implies that looking at only one sector may yield an incomplete view of territorial heterogeneity in a given state. Common conceptualizations of the state imply that strong states provide core public goods, especially order and protection, throughout their territory, and that any deviation from territorial homogeneity is a form of weakness. Our conceptual typology explicitly calls attention to how uniformly the state provides a range of goods, highlighting the need to take a broader view of state activity across the territory.

A particularly urgent question is the compatibility of different types of territorial heterogeneity with democracy. While O’Donnell’s Reference O’Donnell1999 work would lead us to expect more successful democracies in broadly uniform than in disjointed states, it is less clear how differentiated or narrowly uniform states might perform. What is the relationship between democracy at the national level and types of territorial heterogeneity? Which types of states succeed in engaging citizens and in producing programmatic and representative parties? Bridging questions about the regime and the state, we can also ask how successfully different types of states reflect the underlying preferences of the population, instead of viewing these differences through the lens of incomplete or ineffective state formation.

The conceptual typology we present here is agnostic about the origins of territorial heterogeneity, but this question deserves further consideration. Increasing uniformity by extending public goods and sets of rights to peripheral communities is not necessarily a benign process and may be highly contentious (Staniland Reference Staniland2012). The expansion of women’s rights enforcement to indigenous communities in Mexico illustrates this point (Cleary this issue). When studying (successful) attempts to increase uniformity, it is therefore worth considering the extent to which this is a preferred outcome by local communities. To improve the quality of citizens’ lives, what is effective, and desirable, given the type of state that exists? In this way, our typology and the articles in this special issue provide some guidance for contemplating important normative trade-offs between national-level goals of inclusion and representation and subnational autonomy.