In the last two decades, economic historians have paid increasing attention to the construction of real wage and GDP per capita series for premodern economies to learn more about their performance and structural characteristics as well as their standards of living. Detailed real wage series have been developed for leading cities in Europe from the Black Death to the Industrial Revolution, for example. These have provided significant insights into the timing of the divergence in incomes between the northwest and the rest of the Continent (Van Zanden Reference Van Zanden1999; Allen Reference Allen2001; Clark Reference Clark2005; Pamuk Reference Pamuk2007). Similarly, a good deal of effort has been devoted to quantifying wage differentials between different parts of Europe and Asia during the centuries before the Industrial Revolution (Özmucur and Pamuk Reference Özmucur and Pamuk2002; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Bassino, Ma, Moll-Muarata and Luiten Van Zanden2011; Scheidel Reference Scheidel2010). More recently, attempts have also been made to estimate real wages and GDP per capita as well as the degree of income inequality in the ancient and medieval economies, such as Ancient Mesopotamia, Ancient Greece, Roman, and Byzantine Empires.Footnote 1

This study aims to establish long-term trends in the purchasing power of the wages of unskilled urban workers and develop preliminary estimates for GDP per capita for parts of the Middle East during the medieval era. We also offer some comparisons with other preindustrial economies across time and space. Although, the Middle East had one of the most vibrant medieval economies through the end of the eleventh century, it has been underrepresented if not conspicuously absent in the recent literature. Located between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean and at the center major intercontinental trade routes, the region enjoyed a strong urban network and wide range of manufacturing activities. Middle Eastern merchants also developed complex institutions including credit arrangements, commercial and other business partnerships, long-distance trade, and shipping contracting. After the eleventh century, however, the center of gravity of the medieval world shifted away from the urban centers of the Middle East towards those of Italy (Ashtor Reference Ashtor1976; Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod1989; Shatzmiller Reference Shatzmiller2011; Findlay and O'Rourke 2007, pp. 48–61 and 88–101; Udovitch Reference Udovitch1962; Issawi Reference Issawi1980).

Slave labor existed in the Middle East during the medieval era, but most urban labor was not coerced. It was either self-employed or paid a wage. One conclusion we reach in this study is that two powerful and long-lasting demographic shocks caused large and long-term changes in the purchasing power of wages and per capita incomes in the medieval Middle East. As is well-known for Europe and the Middle East, wages rose sharply and remained high during the Black Death that began in the middle of the fourteenth century and lasted until the sixteenth century and even later (Herlihy Reference Herlihy1997; Pamuk Reference Pamuk2007; Voigtlander and Voth Reference Voigtlander and Voth2009; Dols Reference Dols1977; Borsch Reference Borsch2005). Our evidence indicates that the Justinian Plague that began in the sixth century and lasted at least until the middle of the eighth century had equally profound consequences on wages and per capita incomes. In both episodes, population recovered slowly in part because the plague kept recurring and because fertility also seems to have remained low. Wages did not remain permanently high, however, and they began to decline after more than two centuries.

Our study of wages also sheds light on the causes of economic prosperity during the so-called Golden Age of Islam, which centered in Iraq from the eighth to the tenth centuries. Our knowledge about this episode is limited but it is clear this was a period of intensive growth including expansion of irrigation, productivity increases in agriculture, higher rates of urbanization, growth of manufacturing, development of long-distance trade, and a burst of technical innovation as well as cultural achievements. Our calculations indicate that wages of unskilled workers as well as average incomes was significantly above the subsistence minimum during this period. Such episodes of “economic efflorescence” occurred many times if not often in the Old World during the millennia before the Industrial Revolution (Goldstone Reference Goldstone2002, pp. 339–59). Our wage series also suggest that the environment of labor shortages, high labor incomes and high per capita wealth in the aftermath of the Justinian Plague stimulated agricultural productivity, the urban economy, and long-distance trade by creating demand for income elastic goods, both domestic and imported.

Our findings thus suggest that the view that preindustrial societies were always or mostly near the edge of subsistence is mistaken. In fact, both the purchasing power of the daily wages of unskilled workers and average incomes in the Middle East exhibited significant medium- and long-term fluctuations. Both also remained well above the subsistence minimum for much of the medieval era. We estimate that the purchasing power of unskilled wages in the region fluctuated mostly between 1.3 and 2 times subsistence minimum and average incomes remained mostly within an interval that ranged from 2 to 3 times the subsistence minimum during the medieval era.

SOURCES AND DATA COLLECTION

Medieval Middle Eastern sources contain abundant price and to a lesser extent wage data. For the urban areas in Lower Egypt (Fustāt, Cairo, and some other cities), one source is the Arab chroniclers who provide price observations more frequently, if not mostly, for periods of great abundance or famine, or periods of unusual lows and highs. In contrast, data from two other main categories of primary sources, papyri and the Geniza documents offer price and wage data for “normal” times as recorded in contemporary contracts and accounts. As a result, they are usually more useful than the chroniclers. The papyri are private and administrative documents written in Greek, Coptic, or Arabic. Tens of thousands of papyri documents are housed in libraries around the world and in various degrees of conservation. They allow us to cover better seventh through the tenth centuries.Footnote 2

The Geniza documents refer to more than 350,000 private and administrative accounts and literary texts mainly covering from eleventh through the thirteenth centuries. They are written mostly in the local Arabic language of the time but in Hebrew characters by members of the Jewish community and were preserved in the synagogue of Fustāt-Cairo. The documents used here, such as merchants’ accounts, relate to a variety of economic transactions by individuals and expenses by public institutions. They refer mostly to dealings between Jews but they provide information on economic conditions not only in Egypt but also in North Africa, Sicily, Syria-Palestine, and Iraq (Goitein Reference Goitein1967, vol. I, pp. 9–17).

In addition, waqf making documents from Mamluk Egypt offer a good deal of price and to a lesser extent wage data for the thirteenth through the fifteenth centuries. Similarly, the Italian, French, and Catalan archives documenting trade with Egypt provide some commodity prices during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The wage and price data used in our calculations for Egypt were selected partly from the documents themselves and partly from studies devoted to them such as S. D. Goitein's Mediterranean Society (1967 and Reference Goitein1971), and Eliyahu Ashtor's Prix et Salaires (1969).Footnote 3

There are no archival documents available for medieval Iraq. Government correspondence written on papyri imported from Egypt did not survive in the humid climate. However, after the introduction and spread of paper during the eighth and ninth centuries, the region experienced a burst of literary activity which resulted in an array of book length manuscripts many of which have survived. Some of these include price and wage observations. Among them are geographical works known as Books of Routes and Kingdoms, kutūb al-masālik wa'l-mamālik, mostly written in the ninth and tenth centuries by authors such as Abū ‘l-Hasan Ali b. al-Husayn al-Mascūdī and Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Muqaddasī, and chronicles written by historians such as Muhammad b. Jarīr al-Tabarī, Hilāl b. Muhassin al-Sābī, and Muhammad b. Abdus al-Jahshiyārī. They provide wage and price information mostly for Baghdad. A list of the sources for the wage and price observations we have used in our calculations for Fustāt-Cairo and for Baghdad is presented by period in Table 1.

Independent observations of unskilled urban workers’ wages in these sources are not very large. For Egypt, our efforts produced about a dozen observations for the early period 700 to 1000 and about a dozen observations for the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In addition, the same sources provide larger numbers of observations for wages of various kinds of skilled workers which were helpful for placing the unskilled wages in context. In contrast, the Geniza documents yielded many dozens of wage observations for urban unskilled workers for the period eleventh through the thirteenth centuries. For Iraq, we uncovered less than a dozen observations for the early period 750 to 1000 and less than a dozen observations for the later period 1000 to 1258. For Iraq too, the same sources provide larger numbers of observations for wages of various kinds of skilled workers. These observations are mostly for monthly wages, usually stated to be 25 working days, and in gold dinars, but some daily wages are given in terms of the local silver currency. Most wage observations for unskilled workers excluded or did not mention additional food or lunch. Food in addition to the money wage is mentioned more often for skilled workers. When the sources stated that some form of food was provided to the unskilled workers, we added roughly one-fifth of the money wage. As was the case in most preindustrial societies, nominal wages available from these sources were often slow to change. The medium- and longer-term fluctuations in nominal as well as real wages indicate, however, that they did respond to changes in supply and demand.

TABLE 1 SOURCES FOR PRICES AND WAGES IN EGYPT AND IRAQ, 720–1480

Sources:

For full details of the sources, see References.

The volume of evidence on prices is larger although not large enough to build annual series. However, prices were also less stable than nominal wages. This was especially true for wheat prices which were usually expressed in gold dinars per irdabb (70 kilograms). Moreover, the available price observations are biased towards the extraordinary years, since extraordinarily high and low prices arising from fluctuations in the weather or in the level of the Nile, in the case of Egypt, were recorded more often in the sources.Footnote 4 We tried, instead, to identify and use average or “normal” wheat prices associated with “average” harvests as cited by the observers for each benchmark year. Short-term price fluctuations were more limited in the case of other goods, especially nonfood items.

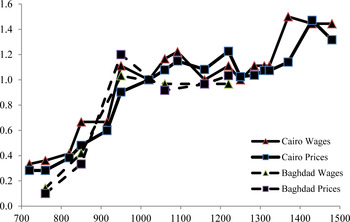

PURCHASING POWER OF THE WAGES OF UNSKILLED WORKERS

Table 2 presents the prices of the leading items of consumption in Fustāt-Cairo and the prices of wheat in Baghdad as well as the nominal monthly wages of unskilled urban workers for our benchmark years. Prices provided in Table 2 together with price data for a few other commodities enabled us to calculate a simple consumer price index for Fustāt-Cairo and another index for wheat prices in Baghdad (see Figure 1). In the calculation of the consumer price level, we tried to use the basket of the average consumer and for that purpose employed a mixture of the respectability and bare-bones baskets which will be discussed below. We also chose to present the long-term price and nominal wage indices in terms of gold because although many prices and some nominal wages are available in terms of the silver dirham, there is often uncertainty regarding the silver content of the dirham while data on the exchange rates between the silver dirham and the gold dinar and the gold content of the dinar are more reliable. Furthermore, in late medieval Egypt prices began to be quoted mostly in copper and gold as silver coinage disappeared. Figure 1 makes clear that consumer price levels in Egypt expressed in gold rose significantly from the eighth through the tenth centuries and then fluctuated within a more narrow range before rising again in the fourteenth century. Prices of wheat and other goods for which we have evidence showed similar increases in Baghdad from the eighth to the tenth centuries. As a result, we can conclude that prices in Egypt and Iraq expressed in gold, as well as silver, were significantly higher at the end of the tenth century in comparison to both the end of the Roman or Byzantine eras and the beginning of the Islamic era in the seventh or eighth centuries. These rising trends in prices and nominal wages are probably related to the growing availability of specie in the region during the early centuries of Islam and it would be interesting to see to what extent the same increase occurred in other parts of the Old World.

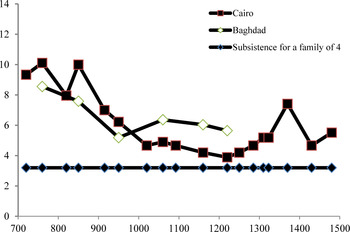

Comparing the purchasing power of real wages of specific occupations, most often of unskilled construction workers in leading cities in a region or country has long been a basic approach for comparing levels of per capita income or the standards of living. Real wage data are of far better quality than per capita GDP estimates especially for earlier periods for which other data is often limited. The most basic way to calculate the purchasing power of daily wages would be in terms of wheat or bread. It may also be the only way to do so if prices for other consumer goods are not available. Figure 2 presents the purchasing power of the daily wages of unskilled, urban, male workers in Fustāt-Cairo and Baghdad in terms of the kilograms of wheat for the benchmark years for which both wage and price data exist. Figure 2 indicates that not only were there large changes over time in the purchasing power of daily wages ranging between more than 10 kilos to 3.5 kilos of wheat but also suggests that there were differences in the wage levels between Fustāt-Cairo and Baghdad and more generally between Egypt and Iraq. We will elaborate on the reasons for these differences below.

One important question at this stage would be to relate these wheat wages to the subsistence minimum. It is not easy to express the level of the subsistence minimum in wheat equivalents but estimates have been given ranging from 250 kilos to 300 kilos per person per year (Scheidel and Friesen Reference Scheidel and Friesen2009; Lindert, Milanovich, and Williamson Reference Lindert, Milanovich and Williamson2007). Under the assumption 250 working days a year and a family of four, two adults and two children as the household of a wage worker, we arrive at a range of 3.2 to 3.7 kilograms of wheat equivalents per day as the subsistence minimum for the purchasing power of the daily wage. Our calculations summarized in Figure 1 thus suggest that daily wages of unskilled urban workers in Egypt and in Iraq were generally above the subsistence during the medieval era. Moreover, from the eighth to the tenth centuries and again during the fourteenth century, the purchasing power of wages in Egypt was quite high.

It is possible that the high purchasing power of urban unskilled wages shown in Figure 2 exaggerates the living standards of the unskilled urban workers especially during the eighth to the tenth centuries and during the fourteenth century because these workers may have worked less than 250 days at these rates (Hatcher Reference Hatcher, Dodds and Liddy2011). However, urban unskilled workers did not have to work 250 days a year to attain these standards of living. Indeed, it is likely that their employment fluctuated but the income of the male wage earner was often supplemented by the returns to the labors of other members of the household, thanks to small-scale gardening, animal husbandry, and other activities as well as wage labor. Nonetheless, we chose to use the 250 days in order to facilitate intertemporal and interregional comparisons. Moreover, two surviving children per urban household may seem low to the modern observer, yet it is a reasonable number in view of what we know about the fertility behavior and rates of infant mortality in Middle Eastern cities at the time. Many studies state that average size of urban households in the medieval Middle East were below four.Footnote 5 At any rate, in cases where there were more surviving children, they either worked to add to the household income or the amount of time they lived with the household tended to be limited.

For most economies before the early modern era, it would not be possible to go beyond the calculation of the wheat or grain wage. However, for Cairo and to a limited extent for Baghdad we have data on the prices of a wider range of consumer goods and can calculate the purchasing power of daily wages in terms of a standard basket of consumer goods. The same data also give us insights into the long-term trends in the general price level for the medieval Middle East. Two different consumer baskets have been developed in recent years for more detailed comparisons of the purchasing power of daily wages across time and space (Allen Reference Allen2001, Reference Allen, Bowman and Wilson2009). A respectability basket was established primarily after studying the consumption patterns of European workers in the late medieval and early modern eras. It contains the following items with fixed weights: wheat or rye bread, beans/peas, meat, butter or olive oil, cheese, eggs, beer or wine, soap, linen, candle, fuel, and housing. This basket yields approximately 1,940 calories per day. Multiplying its cost by three, gives the cost of maintaining a family of four, consisting of a man, a woman, and two children.

The problem with the respectability basket is that it was too costly for most people in premodern economies including most of medieval and early modern Europe and the Middle East. For this reason, Robert C. Allen and others have found it more realistic to employ another basket called the bare-bones basket which allows lower income consumers to acquire the same level of daily calories at 40 to 50 percent of the cost of the respectability basket. This is achieved by significantly lowering the consumption of animal protein, meat, cheese, and eggs as well as alcohol and shifting to lower priced grains.

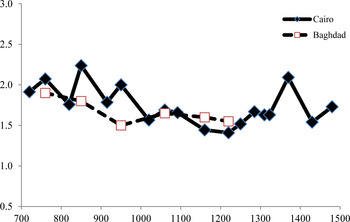

Given our focus on unskilled workers, we chose to do our calculations in terms of the bare-bones basket. We were not able to do this fully, however, as prices of lower-quality grains were not always available, for example. The Mediterranean bare-bones basket yielding approximately 1,940 calories per day for one person for one year which we employed in our calculations included the following: 172 kilograms of wheat, 20 kilos of beans, 5 kilos of meat, 8 kilos of olive oil, which included an allowance for soap, 3 meters of linen, and 15 percent of the total cost of previous items for fuel and rent. In cases where price data for one of these items was missing for a benchmark year, we estimated it by making use of the prices of other items for the same year.Footnote 6 Figure 3 presents the long-term trends in the purchasing power of the daily wages of unskilled male workers in the urban areas of Egypt and Iraq during the medieval era, from the rise of Islam to the end of the fifteenth century in terms of the Mediterranean bare-bones basket for a family of four. Wheat had the largest share and its total cost in this bare-bones basket ranged from 30 percent in the eighth century, when the relative price of wheat was exceptionally low, to 60 percent in the tenth and eleventh centuries and averaged around 50 percent for Fustāt-Cairo in the medieval era. For Baghdad, our estimates of the trajectory of the purchasing power of wages is subject to a higher margin of error because we have limited data on commodities other than wheat. For that reason, we chose to present that trend with a broken line in Figure 3. A good deal of additional evidence, mostly from chroniclers and others, corroborate that pattern, however.Footnote 7

We know that the purchasing power of the wages of unskilled workers occasionally declined below subsistence because of sharp increases in wheat and to a lesser extent in other food prices, due to weather, floods, famine, wars, and other events. However, since we have used only the long-term average or “normal” prices of grains, our calculations do not take into account these shorter-term fluctuations in the purchasing power of wages; 1530s has been examined in some detail. Figure 3 indicates that the long-term purchasing power of unskilled urban wages fluctuated within a more narrow range, from somewhere above subsistence to an upper range which was more than twice as high as the subsistence minimum during these eight centuries.

PLAGUES AND WAGES

As summarized in Tables 3a and 3b, the medieval Middle East experienced two long bouts of plague. Both the Justinian Plague and the Black Death were followed by many recurrences. We know less about the impact of the Justinian Plague that broke out in 541 AD and recurred through the eighth century and even longer in some areas.Footnote 8 In contrast, the impact of the Black Death that struck 1347 and then recurred through the 1530s has been examined in some detail.Footnote 9 While we have estimates regarding the mortality caused by the initial plagues, we know much less about the loss of life associated with each of the many recurrences. Moreover, the evidence on wages and prices for both of these periods is not very detailed. For these reasons, it is not possible to evaluate the impact of any one of the recurrences on the level of wages. In our view, these demographic shocks and the slow recovery of the population afterwards were key determinants of labor market outcomes namely the long-term changes in the purchasing power of wages in the medieval Middle East as shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Our knowledge of the economic impact of such long-lasting plagues is based mostly on the experience of Europe during the Black Death and is broadly consistent with what we would expect on the basis of economic theory. With the decline in population, total output went down sharply, but less so than population. Thus, output per capita increased after the initial impact of the plague. The jump in the land-labor ratio resulted in dramatic changes in relative factor prices and in the sectoral terms of trade. Real wages rose sharply in the decades following the first occurrence of the plague. Higher per capita wealth, per capita incomes, and higher labor incomes also led to major changes in patterns of demand, relative prices, and output. Prices of agricultural goods declined relative to manufactures, especially manufactures with high labor content and labor cost. Land rents as well as interest rates went down both in absolute terms and relative to wages. Owners of land began to lose while incomes of laborers, peasants, and women rose (Herlihy Reference Herlihy1997, pp. 39–57; Findlay and Lundahl Reference Findlay, Lundahl, Findlay, Jonung and Lundahl2002, Reference Findlay, Lundahl, Findlay, Henriksson, Londgern and Lundahl2006; Pamuk Reference Pamuk2007; Voigtlander and Voth Reference Voigtlander and Voth2009).

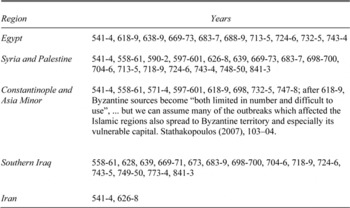

Table 3a EVIDENCE ON THE JUSTINIAN PLAGUE AND ITS RECURRENCES IN THE MIDDLE EAST

Notes:

Most authors conclude that the Justinian Plague disappeared from the eastern Mediterranean in the middle of the eighth century. However, based on the Syriac chronicles, Morony (Reference Morony and Little2007, pp. 61–73) has recently argued that it may have persisted until the ninth century in Syria and Iraq.

Sources:

Dols (Reference Dols1974); Conrad (Reference Conrad1981); Morony (Reference Morony and Little2007); Stathakopoulos (Reference Stathakopoulos and Little2007).

Table 3b EVIDENCE ON THE BLACK DEATH AND ITS RECURRENCES IN THE MIDDLE EAST

Sources:

Dols (Reference Dols1977); Marien (Reference Marien2009).

With higher per capita wealth and incomes and changes in the distribution of income in favor of labor, patterns of demand also began to change from basic goods and necessities towards goods with higher income elasticity or luxuries. The composition of agricultural output thus shifted from cereals towards other crops. There was a rise in land intensive activities, most notably sheep and cattle raising. There were similar changes in the composition of manufactured goods and services. The rise in wages and per capita incomes were not always sustainable, however. Where the decline in population led to the decline of agriculture or trade, per capita incomes came down more quickly. Either way, mortality rates eventually fell as the plague lost momentum. How quickly population began to recover, however, depended upon a host of factors. In addition to the recurrences of the plague, low levels of fertility tended to slow down population recovery. In both respects, there were important differences between different regions. As population began to increase, so did output and new and less productive land was brought under cultivation. Wages and per capita incomes then began to decline towards their pre-plague levels in both agriculture and the urban economy (Herlihy Reference Herlihy1997, pp. 39–57; Findlay and Lundahl Reference Findlay, Lundahl, Findlay, Jonung and Lundahl2002 and Reference Findlay, Lundahl, Findlay, Henriksson, Londgern and Lundahl2006; Voigtlander and Voth Reference Voigtlander and Voth2009). For the Middle East, several studies have attempted to examine the economic consequences of the Black Death in Egypt with mixed results (Lopez, Miskimin, and Udovitch Reference Lopez, Miskimin, Udovitch and Cook1970, pp. 115–28; Dols Reference Dols1977, pp. 255–80; and Borsch Reference Borsch2005).

Since more is known about the impact of the Black Death in the Middle East, we will begin with that latter plague. For Egypt, it has been estimated that roughly one-quarter to one-third of the population died and the economy contracted sharply beginning in 1347. The population then continued to decline until the end of the fifteenth century and the total fall may have topped 40 percent due to the recurrences of the plague as can be seen from Table 3b (Dols Reference Dols1977, pp. 193–235 and Reference Dols and Udovitch1981). However, the incomes of those who survived were often higher, at least initially (See Figure 3). Even though direct observations of daily or monthly wages of urban unskilled workers are scarce for the Black Death era, the voluminous writings of the chronicler Ahmad ibn cAlī al-Maqrīzī leave no doubt that after the initial impact of the plague, wages of unskilled as well as skilled workers rose (al-Maqrīzī Reference Quatremère1845, Reference Wiet1962; Dols Reference Dols1977, pp. 257–71; Ashtor 1966, pp. 372–74). Yet, just as the longer-term trajectory of wages and economic consequences may have differed between southern and northwestern Europe (Pamuk Reference Pamuk2007), we should not expect the longer-term economic impact of the Black Death in the Middle East to be similar to that in one region or other of Europe. Stuart Borsch has recently suggested, for example, that because agriculture in Egypt required the regular maintenance of irrigation systems, labor shortages in the aftermath of the Black Death may have led to their disrepair and decline in agricultural productivity and per capita income (Borsch Reference Borsch2005, pp. 40–66).Footnote 10 Elsewhere in the Middle East, the initial outbreak of the plague and its recurrences had a lasting impact on Syria and the Byzantine Empire including Constantinople and Asia Minor or present- day Turkey (see Table 3b).Footnote 11 While reliable estimates on the decline of population during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries are lacking for Syria and Asia Minor, estimates based on Ottoman archival sources indicate that the population of Asia Minor increased by about one-third during the sixteenth century (Barkan Reference Barkan and Cook1970). In contrast, information about the impact of the Black Death on Iraq is very limited. No wage evidence has been uncovered on Iraq for this period.

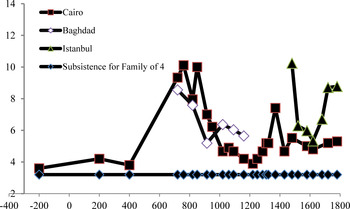

In Figures 4 and 5, we extend the trajectory of urban unskilled wages in Cairo and Constantinople-Istanbul into the early modern era.Footnote 12 These figures indicate that wages of unskilled workers in Cairo declined somewhat in the second half of the fourteenth century and the first half of the fifteenth century. In contrast, in Ottoman Istanbul, they were still quite high at the end of the fifteenth century but began to decline with the increase of population during the sixteenth century. Moreover, in both cities the post-Black Death peak in wages was not surpassed during the early modern era. At the end of the eighteenth century, wages in both Cairo and Istanbul were not higher than their levels at the end of the fifteenth century.

As summarized in Table 3a, there is a good deal of evidence now regarding the Justinian Plague. Some historians as well as archeologists of Late Antiquity had been skeptical of its impact (Banaji Reference Banaji2001, pp. 16–20; Magness Reference Magness2003). Recent archeological work, however, points to abandoned towns and villages and more generally demographic decline in Egypt, Syria-Palestine, and Iraq beginning in the sixth century (Alston Reference Alston and Scheidel2001; Kennedy Reference Kennedy and Little2007; Adams Reference Adams1965). Michaels Dols (Reference Dols1974) had listed six major epidemics ravaging the region between 627 and 717. More recently, Dionysios Stathakopoulos (Reference Stathakopoulos and Little2007) has provided more detailed evidence regarding the recurrences of the plague until the eighth century, which is included in Table 3a. The plague was at least partly responsible for the collapse of the Byzantine military system which allowed the Sassanid army to easily conquer Egypt and Syria-Palestine during the first two decades of the seventh century and the ease of the Islamic conquest in the following decades (Cameron Reference Cameron1993, pp. 186–96; Foss Reference Foss1975). It is also likely that the plague had less impact on the Arabian Peninsula which helps explain the Islamic expansion in the rest of the region (Pellat Reference Pellat1971).

Population figures for this period are not very reliable and they should be treated as no more than best guesses. However, the broad picture offered by the existing estimates does point to heavy loss of population due to the plague and slow recovery beginning during or after the eighth century. Warren Treadgold (Reference Treadgold1997, p. 278) suggests that the Byzantine Empire's population fell from a high of 26 million in 540 just before the outbreak of the plague, to 17 million in 610 when the Byzantine Empire still included Egypt and Syria as well as Asia Minor and further declines after that date. Angeliki Laiou and Cecile Morrison (Reference Laiou and Morisson2007, pp. 38–39) identify the Justinian Plague as a turning point in the economic history of the Byzantine Empire and estimate that the plague and its recurrences until the eighth century may have reduced the population by as much as 30 percent. Treadgold, Laiou and Morrison, and Stathakopoulos (2008) all point to demographic and economic recovery beginning late in the eighth century or early in the ninth century. Charles Issawi (Reference Issawi and Udovitch1981) confirms the same pattern of sharp decline in most parts of the region beginning in the sixth century followed by recovery of about 25 percent from the middle of the eighth century until about 1000.

The existing estimates of population for Egypt and Iraq before and after the Justinian plague are also subject to a high degree of uncertainty. These estimates do indicate, however, that the decline of population from the middle of the sixth century until the end of the eighth century was greater in Egypt and in Syria than it was in Iraq. Josiah C. Russell argues, for example, that the population of Egypt may have declined by as much as one third or more from the middle of the sixth century to the tenth or eleventh century. It then began to increase and may have doubled until the Black Death in the fourteenth century (Russell Reference Russell1966; Dols Reference Dols1974; McEvedy and Jones Reference McEvedy and Jones1978). Ashtor also emphasizes that the population of Egypt increased significantly from the eighth to the eleventh centuries but declined at the beginning of the thirteenth century (Issawi Reference Issawi and Udovitch1981, pp. 384–85).

The population and cultivated area in Iraq also declined in the aftermath of the Justinian Plague, but it began to recover much sooner. This was in large part due to the new Islamic rulers’ encouragement of migration from Arabia and elsewhere (Adams Reference Adams1965, pp. 74–81; Lapidus Reference Lapidus and Udovitch1981, pp. 41–53). As a result, some scholars estimate that by the eighth and ninth centuries the population of Iraq exceeded the levels in the sixth century. For the ninth century, the descriptions of the Arab geographers leave the impression of a thickly settled and intensely cultivated country (Issawi Reference Issawi and Udovitch1981, p. 386). Although there are higher estimates, the population of Baghdad during the ninth and tenth centuries was probably somewhere between 300,000 and 400,000. Together with the population of other urban centers such as Basra, Kufa, Wasit, and others, the share of urban population must have been above 20 percent of the total population of Iraq.Footnote 13

Our wage and price data allow us to examine the impact of the Justinian Plague for the first time from this perspective not only for the Middle East but for anywhere in the Old World. The wage and price evidence presented in Figures 2, 3, and 4 begins for Egypt not with the outbreak of the plague in the sixth century but early in the eighth century. However, the data are consistent with demographic decline due to the Justinian Plague and its recurrences until the middle of the eighth century. First, they show that the purchasing power of the wages of urban unskilled workers in Egypt during the eighth and ninth centuries was much higher than those in Egypt during the Hellenistic and Roman eras (Scheidel Reference Scheidel2010a, pp. 443–44; and Allen Reference Allen, Bowman and Wilson2009) as well as those in Egypt during the later centuries. It is highly unlikely that the purchasing power of wages had been this high during the Roman period. In another recent and unpublished paper, Walter Scheidel has argued that wages in Roman Egypt increased by about 20 percent in the aftermath of the Antonine Plague in 165 AD but declined subsequently. In the same paper, he points to the high level of wheat wages in Egypt during the seventh and eighth centuries and links it to the Justinian Plague (Scheidel Reference Scheidel2010b, pp. 15–23). Finally, a good deal of qualitative evidence from contemporary sources also indicate that the purchasing power of unskilled wages showed short- and medium-term fluctuations but remained quite high during the eighth and ninth centuries (Ashtor Reference Ashtor1968, pp. 90–93).

The evidence also indicates that while nominal wages rose sharply, relative prices moved against agricultural products. Both the absolute and relative price of wheat in Egypt was lower during the eighth and ninth centuries than any later period during the medieval era. As a result, the rise in wheat wages was stronger than the rise in the purchasing power of the wages in terms of the bare-bones basket during this period as can be seen from a comparison of Figures 2 and 3. These low prices of wheat in Egypt were probably related also to the impact of the plague beyond Egypt. In the earlier period, Egypt had been a major exporter of wheat to the rest of Byzantine Empire. When the population of the Byzantine Empire and especially of Constantinople declined after the Justinian Plague and its recurrences, demand for wheat from Egypt also dropped (Teall Reference Teall1959, pp. 91–97).

Data for Iraq during the centuries before and after the Justinian Plague are more limited. While we are unable to say anything about the sixth and seventh centuries, the evidence on wages and prices for Baghdad summarized in Table 2 and Figures 2 and 3 suggests that labor shortages were more intense in Egypt than in Iraq during the eighth and ninth centuries. The purchasing power of wages of unskilled workers in Baghdad was well above subsistence but lower than that in Fustāt-Cairo during these two centuries. This is consistent with an earlier recovery of population in Iraq than in Syria and Egypt led by the large waves of in-migration discussed above. With population recovery, prices of wheat began to rise faster than nominal wages and other prices in both Egypt and Iraq but the decline in the purchasing power of wages during the following centuries was slower and more modest in Iraq as we will discuss in the next section.

The evidence we have analyzed thus point to big drops in population and persistent labor shortages during both plagues in the Middle East. Although the frequent recurrences of the plague are one important reason for the slow recovery of population, it would be also useful to explore, for example, whether the environment of labor shortages and high wages changed, for whatever reason, women's fertility behavior and slowed down the population recovery. This is precisely what Basim Musallam observed: in the aftermath of the Black Death fertility rates in the region remained low. After extensive research in literary, medical, and legal sources, he concluded that birth control was widely practiced in medieval Islamic society. While evidence is scant for the earlier period, his conclusion could be extended to the era of the Justinian Plague. In fact, Musallam has demonstrated that the Islamic law had sanctioned birth control by the ninth century (Musallam Reference Musallam1983). It is likely that longer-term consequences of low levels of fertility in the face of labor shortages extended to other areas and may have played a role in the shaping of other institutions. For example, Islamic law on women's legal rights over reproduction, rights to participate in the labor force as wage laborers and keep their earnings, and women's property rights in general, such as the right to inherit and bequeath, the right to gift, endow, and be gifted, the right to make independent decisions over property, and especially the strict separation of property ownership during marriage, were developed during these early centuries of Islam under the same environment (Shatzmiller Reference Shatzmiller2007, pp. 93–117, 149–75).

HIGH WAGES AND THE GOLDEN AGE

The Middle East region had one of the most vibrant economies in the world from the eighth until the end of the eleventh century, “the Golden Age of Islam.” The prosperity was based, above all, on highly productive agriculture and the gains from long-distance trade. These were, in turn, closely related to political stability, greater security and expansion of irrigation. There is also a good deal of evidence that division of labor expanded and the fraction of the labor force in occupations requiring specific skills increased significantly during this period. In this section, we explore the causal linkages between the high wage environment created by the Justinian Plague and its recurrences and the emergence of the Golden Age and argue that the high wage environment contributed to the rise of the Golden Age. In some respects, this was a process similar to the emergence of new tastes and demand for luxuries in Europe in the aftermath of the Black Death (Herlihy Reference Herlihy1997; Voigtlander and Voth Reference Voigtlander and Voth2009). There were important differences as well. Some of what follows is necessarily speculative as the existing historical literature has not focused adequately on the causal connections between the plague and aspects of the Golden Age.

High levels of wages and per capita wealth contributed to the increases in agricultural productivity in the aftermath of the Justinian Plague through the rise of demand for high income or income elastic goods. Iraq became during this period the first home in the Middle East to a variety of new plants, food plants such as sorghum, rice, lemon and lime, spinach, watermelon, and sugar cane as well as industrial plants including Old World cotton, as described in detail by Andrew Watson.Footnote 14 Evidence from cookery books and more generally about diets also indicate that mutton, lamb, chicken, and dairy products played an important role in the diets of the salaried middle classes, and to a lesser extent of the poor. Since obtaining the same amount of calories from meat and dairy products can be as much as ten times more costly to produce than from grain products, the extent to which meat and dairy products are included in the diets and more generally the contribution of animal husbandry to the economy provides us clues about how far levels of income had moved above the subsistence minimum. The list of ingredients found in cookery books dating from the early Abbasid period also include a wide range of vegetables, fruits, and aromatic herbs also produced by local cultivators (Arberry Reference Arberry1939; Rodinson Reference Rodinson1949, pp. 145–46). The growing demand for labor necessary for the cultivation of the new crops was met in part by the use of imported slaves. However, after the powerful Zanj Rebellion of East African slaves in southern Iraq during 869–883, use of slaves in agriculture declined sharply if not ended entirely (Popovic Reference Popovic1976).

Perhaps the strongest evidence for rising productivity in agriculture in Iraq comes from the urbanization rate which exceeded 20 percent in the eighth century. The dense settlements and high rates of urbanization in southern Iraq described by the Arab geographers of the ninth century were not possible without higher levels of productivity in agriculture and long distance trade. The same high rates of urbanization, however, may have also increased rates of mortality, however. Similarly, the growth of long-distance trade may have made it easier for the disease to spread and prolonged the environment of high wages.

The high wages and the rise of demand for income elastic goods may have also helped the emergence of new tastes and expand demand in the urban economy as well for new products, both domestically produced and imported including more expensive varieties of cloth, household goods, utensils, and others as well as demand for literacy and books. The expansion in demand, in turn, supported the growing specialization within manufacturing industries such as food, textiles, ceramics, ivory, leather, metal, paper, wicker, wood, and others as revealed by a recent compilation of trade names and occupations (Shatzmiller Reference Shatzmiller1994, pp. 101–323). Imported items during this period included more expensive varieties of foodstuffs, cloth and clothing, and household goods. The varieties range of imported ingredients cited in the cookery books were equally wide, including spices such as pepper, ginger, cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, nutmeg from China, India, and East Africa (Arberry Reference Arberry1939; Rodinson Reference Rodinson1949, pp. 145–46). Market transactions were necessary to obtain the cash for these goods and the demand for greater monetization was met by the growing supplies of silver from the mines in Central Asia and elsewhere (Noonan Reference Noonan1986; Burjakov Reference Burjakov and De la Vaissière2008). It is also possible that some of the long and impressive list of technical adaptations and innovations in agriculture and food production, shipbuilding and navigation, textiles, leather and paper, chemicals, soap making, glass and ceramics, mining and metallurgy, mechanical engineering including the use of water power and others that took place during this period represented responses to the same environment of high wages and labor scarcity (Ahmad al-Hassan and Hill Reference al-Hassan and Hill1986; Mokyr Reference Mokyr1990, pp. 39–45). The deepening of the division of labor, the growth of new occupations and skills in manufacturing and services as well as agriculture and the long list of technical innovations all point to an episode of intensive growth and economic efflorescence in Abbasid Iraq of the kind that has been observed many times but not regularly or frequently in the preindustrial era (Goldstone Reference Goldstone2002, pp. 339–59; Jones Reference Jones1988). These developments must have raised productivity and help explain why the purchasing power of wages declined less in Iraq than in Egypt despite the more rapid and stronger recovery of population in the aftermath of the Justinian Plague and why wages of urban unskilled workers did not go down to the levels of subsistence (Figures 2 and 3).

This interaction between the environment of high wages that emerged in the aftermath of the Justinian Plague and the Golden Age in Iraq was not the only possible outcome, however. While the Black Death led to sharply higher wages in Egypt in the near term, longer consequences may have been very different. It has been suggested that the labor shortages and fiscal difficulties in the aftermath of the Black Death led to deteriorating infrastructure in irrigation and declining productivity in agriculture. In short, one cannot talk about the same pattern in the aftermath of each and every plague. Conditions of high mortality and high wages interacted differently with different geography, institutions, and other existing conditions to produce different outcomes.

ESTIMATES FOR GDP PER CAPITA

An alternative method for comparisons of income and standards of living across time and space is to construct estimates of GDP per capita or average income. Until recently, GDP per capita in most medieval and ancient economies was assumed to remain close to subsistence levels. With growing interest in recent years in medieval and ancient economies, however, new estimates began to emerge which suggest that GDP per capita was often significantly higher than the subsistence minimum, even if some large fraction of the population lived close to subsistence, others had significantly higher levels of income and consumption, pushing the averages higher.

Due to the absence of data, modern methods of constructing GDP cannot be applied to the medieval Middle East. Indeed estimates of both total population and production are subject to large margins of error. We adopt, instead, an income side approach and begin with the purchasing power of the wages of unskilled workers and then proceed by making some assumptions about the structure of the economy, the labor force and income distribution. The purchasing power of the wages of unskilled urban workers in terms of the bare-bones basket reflects the average purchasing power for those segments of the population whose incomes were derived from unskilled labor. However, due to the presence of higher income groups whose incomes are derived from skilled labor as well as ownership or control of land and capital, average incomes for the economy as a whole were higher than the average incomes of unskilled urban and landless agricultural workers. Recent data gathered on inequality in preindustrial societies suggest that average incomes were usually 1.5 to 2 times the wages of landless agricultural workers (Lindert, Milanovich, and Williamson Reference Lindert, Milanovich and Williamson2007). We should expect that the ratio of average incomes or GDP per capita to the urban unskilled wage or k for short would vary in preindustrial economies within a similar range depending upon a number of factors including the rate of urbanization and the degree of complexity of the economy. Even in the case of the same economy, we should expect k to vary over time depending on the position of urban unskilled wages in the income hierarchy and the structure of income inequality.Footnote 15 For example, the larger share of the skilled workers in the labor force and the larger size of manufacturing incomes in Iraq during the Golden Age suggest that GDP per capita exceeded the incomes of unskilled wage laborers by a larger margin.Footnote 16 For this reason, we should expect that the ratio between GDP per capita and the average incomes of households dependent on the unskilled wage was higher in Iraq during the Golden Age.

TABLE 4 ESTIMATES FOR GDP PER CAPITA FOR MEDIEVAL EGYPT AND IRAQ

Note:

The estimate for GDP per capita given in column 3 is obtained by multiplying columns 1 and 2 by 275, which is the estimate for subsistence level of GDP per capita expressed in 1990 U.S. dollars.

Moreover, in view of the importance of demographic cycles in the determination of wages and the distribution of income in the medieval Middle East, it is most likely that k also varied over the demographic cycle depending upon the extent of the labor shortages. We expect that the ratio of incomes derived from skilled labor, land, and capital to the average unskilled wage was higher during periods when population was relatively high and wages relatively low and the opposite occurred when population began to recover. In other words, average incomes for the population as a whole did not necessarily move together with the purchasing power of the wages of urban unskilled workers during the demographic cycle (Hatcher Reference Hatcher, Dodds and Liddy2011). Nonetheless, in the absence of additional information about the structure of income inequality, it is difficult to arrive at point estimates for k and in turn for GDP per capita for any part of the medieval era. Given the limitations of the available evidence, the best we can do is to offer a range for both k and for GDP per capita for each of the benchmark years (Table 4).Footnote 17

Accordingly, from purchasing power of urban unskilled wages, we estimate that the peak for GDP per capita in the medieval Middle East was reached in southern Iraq during the second half of the eighth century or early in the ninth century at somewhere between 890 and 990 in purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted 1990 U.S. dollars as used in the Maddison estimates. The peak in GDP per capita in medieval Lower Egypt was reached also during the eighth century at an estimated range between 800 and 910 dollars. We similarly estimate that the low point in GDP per capita in these two areas during the medieval era was reached in Lower Egypt when GDP per capita fell to a range of 590 to 680 dollars during the second half of the twelfth and early thirteenth century (Table 4). In the short term, due to a poor harvest, GDP per capita may have declined to even lower levels. Nevertheless they remained well above the subsistence minimum level of GDP per capita, usually considered to be around 250 to 300 in PPP adjusted 1990 U.S. dollars.

CONCLUSIONS

This article provides insights not only into the economies of the Middle East during the medieval period but also more generally into the comparative study of the preindustrial economies of Europe and the Mediterranean. We have tried to establish the long-term trends in the purchasing power of urban wages and develop some preliminary estimates for GDP per capita for Egypt and Iraq from the eighth to the fifteenth centuries. We were also able to combine these with detailed wage and price information for the Ottoman era to extend our wage series to the end of the eighteenth century.

Our quantitative work suggests that one important determinant of the long-term changes in the purchasing power of wages and average incomes in the medieval Middle East was the demographic shocks. Each of these plagues caused the death of large fractions of the total population but they also led to higher levels consumption and standards of living. These were not simple demographic cycles, however. Population recovery was not rapid not only because of the frequent recurrences of the plague but also because of low levels fertility which may have been supported by institutional including legal changes. Eventually, with some partial if not full recovery of the population, both real wages and per capita incomes began to decline from these high levels. This pattern is reasonably well-known and had been studied in some detail in the case of the Black Death in Europe and to a lesser extent in the Middle East. Less well-known until recently is the impact of the Justinian Plague. The wage and price evidence for Egypt and to a lesser extent for Iraq makes clear that the Justinian Plague had a similar and long-lasting impact in the region.

The environment of labor shortages, high labor incomes, and high per capita wealth in the aftermath of these plagues could stimulate increases in productivity in agriculture, urban economy, and long-distance trade by creating demand for income elastic goods, both domestic and imported. The so-called Golden Age of Islam which was centered in Iraq from the eighth through the tenth centuries and which included expansion of irrigation, productivity increases in agriculture, greater urbanization, expansion of manufacturing, development of long-distance trade, and possibly a burst of technical innovation was one such period. Our calculations indicate that wages of unskilled workers as well as average incomes in Iraq stayed well above the subsistence minimum during this period. The wage increases were not permanent, however, and they did decline as the favorable conditions faded or disappeared.

The evidence we have presented also shows that one can no longer simplify preindustrial societies as economies on the edge of subsistence. Wages of unskilled urban workers approached the subsistence minimum and may have even gone below that minimum at times, especially during periods of harvest failure. However, both because of slow recovery of population during the long lasting demographic cycles and one episode of intensive growth, the purchasing power of the daily wages of unskilled workers as well as the average incomes in the Middle East remained above the subsistence minimum for large part of the medieval era.

Finally, our real wage and to a lesser extent GDP per capita series help us better understand the relative performances of the Middle East from antiquity to the early modern era. In what follows, we prefer to interpret our findings qualitatively since the margins of error associated with the existing estimates of real wages and per capita incomes do not allow a high degree of precision. The wage data allow us to talk with greater certainty about the “Golden Age of Islam” in both absolute and relative terms. In the aftermath of the Justinian Plague, during the early centuries of Islam, real wages and per capita incomes in Iraq and Egypt rose well above the subsistence level and well above those for Roman and Byzantine Egypt in the centuries preceding the plague. This environment of high wages and high incomes contributed to and, in turn, was supported by the productivity increases associated with the Golden Age of Islam. As population levels began to recover first in Iraq and then in Egypt, real wages and per capita incomes began to come down. However, because of the period of intensive growth from the eighth through the tenth centuries, productivity, incomes, and standards of living remained significantly above subsistence for long periods of time.

Our calculations as well as the high rates of urbanization and manufacturing output suggest that around the year 1000 and possibly until a later date sometime in the eleventh century, real wages and incomes in the more prosperous regions of the Middle East were comparable if not higher than those in the more prosperous regions of Europe. After that date, however, the divergence between the Middle East and parts of Europe began to emerge. Parts of the Middle East, Iraq, Iran, and Syria but not Egypt were adversely affected by the Mongol invasions during the thirteenth century although the long-term implications of these invasions may not have been as significant as many have assumed. More importantly, southern and later northwestern Europe began to experience increases in per capita incomes, during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries if not earlier. Footnote 18

We can follow the impact of the Black Death in the Middle East from the wage series for both Cairo and Istanbul in Figures 4 and 5. The initial impact in the Middle East was similar to that in most parts of Europe as real wages and per capita incomes rose sharply in both regions. Beyond that basic similarity, however, there was a good deal of variation. The extent to which wages and incomes rose, how long they remained at those high levels, and how rapidly or slowly they came down depended very much on the initial conditions and subsequent developments. Nonetheless, recent research on Europe has been pointing to an important pattern. As population began to recover, real wages began to decline. For most countries in Europe for which we have evidence, real wages in the fifteenth century were higher than those towards the end of the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Similarly, recent GDP per capita estimates for these countries suggest that in many cases average incomes in the 1780s were not higher than the peaks reached in the aftermath of the Black Death during the fifteenth century.Footnote 19 Trends in the Middle East were broadly similar. Our estimates indicate that real wages in Cairo around 1780s were not any higher than the peak levels attained during the fourteenth century. Similarly, real wages in Istanbul towards the end eighteenth century were close to but not higher than their levels at the end of the fifteenth century.