Executive dysfunctions have been linked to antisocial behavior. However, despite a large number of publications in recent decades, it is still unclear whether executive functions are also impaired in psychopathy. The present meta-analysis seeks to present a neuropsychological profile of executive functions in psychopathy and its factors.

Psychopathy is a severe personality disorder characterized by a constellation of affective, interpersonal, and behavioral symptoms (Burghart & Mier, Reference Burghart and Mier2022; De Brito et al., Reference De Brito, Forth, Baskin-Sommers, Brazil, Kimonis, Pardini and Viding2021; Vitacco & Kosson, Reference Vitacco and Kosson2010). These symptoms are typically manifested by a lack of empathy or remorse, manipulativeness, and impulsivity, promoting a pervasive pattern of disregard for the rights of others (De Brito et al., Reference De Brito, Forth, Baskin-Sommers, Brazil, Kimonis, Pardini and Viding2021). While sharing similarities with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), they differ conceptually. ASPD is broader in scope, with a strong focus on criminal conduct, whereas psychopathy emphasizes interpersonal and affective characteristics (De Brito et al., Reference De Brito, Forth, Baskin-Sommers, Brazil, Kimonis, Pardini and Viding2021). This is complemented by a general tendency towards fearlessness and boldness in the face of risks and stressful situations, which has been shown to be a distinguishing trait of psychopathy (Venables, Hall, & Patrick, Reference Venables, Hall and Patrick2014). Most individuals with a diagnosis of psychopathy therefore also meet the diagnostic criteria for ASPD, but not vice versa (Hildebrand & de Ruiter, Reference Hildebrand and de Ruiter2004). Thus, psychopathy is no less devastating to society than ASPD and, in fact, has been referred to as one of the most important constructs in forensic psychology (Gillespie, Jones, & Garofalo, Reference Gillespie, Jones and Garofalo2023).

A diagnosis of psychopathy is generally made using the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R; Hare, Reference Hare2003), a semi-structured interview that divides psychopathy into two factors (Factor 1: Interpersonal/Affective; Factor 2: Chronic Antisocial Lifestyle) or four facets (interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, antisocial; De Brito et al., Reference De Brito, Forth, Baskin-Sommers, Brazil, Kimonis, Pardini and Viding2021). Although considered the gold standard, more economical self-report measures of psychopathy have been developed in recent decades. Most notable are the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale-4 (SRP-4; Paulhus, Neumann, & Hare, Reference Paulhus, Neumann and Hare2017), the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP; Levenson, Kiehl, & Fitzpatrick, Reference Levenson, Kiehl and Fitzpatrick1995), the Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised (PPI-R; Lilienfeld & Widows, Reference Lilienfeld and Widows2005), and the Triarchic Psychopathy Measure (TriPM; Patrick, Fowles, & Krueger, Reference Patrick, Fowles and Krueger2009). While these scales differ to varying degrees in their underlying conceptualization of psychopathy, they all view it as a constellation of personality traits that fall on a continuum, rather than a dichotomous construct (Sellbom, Lilienfeld, Fowler, & McCary, Reference Sellbom, Lilienfeld, Fowler, McCary and Patrick2018). This is an important distinction as it allows for the expansion of psychopathy research in community samples by not strictly categorizing individuals as either psychopathic or non-psychopathic (Hare & Neumann, Reference Hare and Neumann2008).

The etiology of psychopathy is still not fully understood (De Brito et al., Reference De Brito, Forth, Baskin-Sommers, Brazil, Kimonis, Pardini and Viding2021), but is likely the result of a complex interplay of genetic (Frazier, Ferreira, & Gonzales, Reference Frazier, Ferreira and Gonzales2019) and environmental influences (de Ruiter et al., Reference de Ruiter, Burghart, De Silva, Griesbeck Garcia, Mian, Walshe and Zouharova2022; Mariz, Cruz, & Moreira, Reference Mariz, Cruz and Moreira2022). These, in turn, are believed to influence healthy brain functioning, particularly in prefrontal regions (Nummenmaa et al., Reference Nummenmaa, Lukkarinen, Sun, Putkinen, Seppälä, Karjalainen and Tiihonen2021). An important task of the prefrontal lobe is the control of executive functions (EFs; Yuan & Raz, Reference Yuan and Raz2014). EF comprise a set of cognitive processes essential for adaptive and goal-oriented human behavior (Jurado & Rosselli, Reference Jurado and Rosselli2007; Kramer & Stephens, Reference Kramer, Stephens, Aminoff and Daroff2014). Yet, the exact scope of these cognitive processes remains a matter of debate, with little agreement on the ‘core domains’ of EF. Baggetta and Alexander (Reference Baggetta and Alexander2016) reviewed the EF literature and found considerable heterogeneity among studies. They identified a total of 39 different EF domains, many of which were mentioned only once. The two most influential models that emerged from the literature were those proposed by Miyake et al. (Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000) and Diamond (Reference Diamond2013). Both conceptualize EF as a multidimensional construct with three core domains: Inhibition, Shifting, and Working Memory. Inhibition is the ability to ‘control one's attention, behavior, thoughts or emotions to override a strong internal predisposition or external lure, and instead do what's more appropriate or needed’ (Diamond, Reference Diamond2013, p. 137). Shifting describes the ability to ‘change perspectives or approaches to a problem, flexibly adjusting to new demands, rules or priorities’ (Diamond, Reference Diamond2013, p. 137). Working Memory involves the ability to hold information in memory and process it mentally (Diamond, Reference Diamond2013). Where Miyake et al. (Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000) and Diamond (Reference Diamond2013) differ is in their conceptualization of higher-order EF. Only the former postulates the additional existence of a common underlying EF factor that captures interindividual differences in other domains (Baggetta & Alexander, Reference Baggetta and Alexander2016; Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000). While this three-factor unity-diversity perspective has significantly influenced EF research for two decades, its validity compared to other models has only more recently been systematically examined. Karr et al. (Reference Karr, Areshenkoff, Rast, Hofer, Iverson and Garcia-Barrera2018) conducted a re-analysis of latent variable studies testing seven different models. Their findings indicate that none of the tested models converged consistently across all samples. Still, they found strong evidence supporting a unity-diversity perspective, although the specific number of core EF domains remains uncertain. It is therefore recommended to explore additional models beyond those frequently reported in the literature, provided that they address individual EF domains along with a common EF factor (Karr et al., Reference Karr, Areshenkoff, Rast, Hofer, Iverson and Garcia-Barrera2018). While it is neither feasible nor practical to consider all EF domains that have ever been proposed in the literature, one domain that seems crucial to also examine in the context of psychopathy is Planning (Maes & Brazil, Reference Maes and Brazil2013), as it is critical for identifying goals and the steps necessary to achieve them (Kramer & Stephens, Reference Kramer, Stephens, Aminoff and Daroff2014).

It can be expected that frontal lobe impairments and the resulting executive dysfunctions explain some of the symptoms observed in psychopathy. Acquired damages in these areas were found to lead to recklessness, violence, emotional outbursts, and other behaviors that resemble those of antisocial and psychopathic individuals (Anderson, Bechara, Damasio, Tranel, & Damasio, Reference Anderson, Bechara, Damasio, Tranel, Damasio, Berntson and Cacioppo2013; Barrash, Tranel, & Anderson, Reference Barrash, Tranel and Anderson2000; Eslinger, Flaherty-Craig, & Benton, Reference Eslinger, Flaherty-Craig and Benton2004). Moreover, previous research has linked psychopathy to functional and structural deficits in prefrontal areas (Alegria, Radua, & Rubia, Reference Alegria, Radua and Rubia2016; Deming & Koenigs, Reference Deming and Koenigs2020; Poeppl et al., Reference Poeppl, Donges, Mokros, Rupprecht, Fox, Laird and Eickhoff2019). However, the wealth of prior neuropsychological research examining EF deficits in psychopathy is inconsistent. While some studies found an association between psychopathy and poor EFs (e.g. Bagshaw, Gray, & Snowden, Reference Bagshaw, Gray and Snowden2014; Snowden, Gray, Pugh, & Atkinson, Reference Snowden, Gray, Pugh and Atkinson2013), others found no association (e.g. Dolan, Reference Dolan2012; Hart, Forth, & Hare, Reference Hart, Forth and Hare1990; Smith, Arnett, & Newman, Reference Smith, Arnett and Newman1992) or even improved EF performance (e.g. Sellbom & Verona, Reference Sellbom and Verona2007).

Previous meta-analyses that sought to clarify these contradictory findings have not been entirely successful, either because they focused on antisocial behavior in general or were restricted to certain EF tasks. For instance, Morgan & Lilienfeld's (Reference Morgan and Lilienfeld2000) influential meta-analysis explored the relationship between EF deficits and antisocial behavior, which was operationalized by including ASPD, conduct disorder, and psychopathy. Although the authors also performed subgroup analyses specifically for psychopathy, the focus on a broad concept of antisociality makes it challenging to generalize the findings to psychopathic individuals (Ogloff, Campbell, & Shepherd, Reference Ogloff, Campbell and Shepherd2016). More importantly, only psychopathy total scores were considered, which may limit conclusions since research has shown that the individual factors of psychopathy have distinct developmental pathways and neurobiological correlates (Patrick & Drislane, Reference Patrick and Drislane2015). Similar constraints are found in Ogilvie, Stewart, Chan, and Shum (Reference Ogilvie, Stewart, Chan and Shum2011). Despite being an update of Morgan and Lilienfeld (Reference Morgan and Lilienfeld2000) that includes a broader range of EFs and more recent measures of psychopathy, the focus remained on antisocial behavior and psychopathy total scores. In response, Maes and Brazil (Reference Maes and Brazil2013) conducted a systematic review aimed at examining EF performance between psychopathy factors. However, the interpretability of their findings is constrained by a small sample of only eleven studies and a narrative summary of the included articles. The two most recent meta-analyses were performed by Gillespie, Lee, Williams, and Jones (Reference Gillespie, Lee, Williams and Jones2022) and Jansen and Franse (Reference Jansen and Franse2024). The former yielded a statistically significant but small negative relationship between psychopathy and performance on go/no-go and stop signal tasks. Although including many different psychopathy measures and a reasonable number of studies (n = 17), it is limited to only one EF domain, namely inhibition. Jansen and Franse (Reference Jansen and Franse2024), on the other hand, focused on antisocial personality disorder. Psychopathy was only considered as part of a moderator analysis in the form of a total score and aggregated with CU traits.

The present meta-analysis

In view of the inconclusive findings on psychopathy and EF performance and the limits of previous attempts to clarify these discrepancies, we considered it crucial to conduct a comprehensive meta-analysis that comprises not only psychopathy total and factor scores but also a wide range of EF domains. In doing so, we aimed to answer the following questions: (1) is psychopathy related to executive dysfunction; (2) is this association specific to certain psychopathy factors and/or EF domains; and (3) are these effects moderated by other variables?

Methods

Literature search

A systematic literature search was conducted in October 2022 using three online databases (PsycInfo, PubMed, Web of Science; see online Supplementary Table S1 for our search terms). In addition, previous reviews and Google Scholar were manually searched for relevant references.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

To be included, the following criteria had to be met. First, studies needed to assess the association between psychopathy and EF performance using validated measures for both constructs (see below) in either an offender or community sample. Second, sufficient data for effect size calculation had to be reported or sent to us upon request. Third, the samples studied had to be over the age of 18. Gray literature, such as dissertations, was included, while single case studies or articles that did not report primary data were not.

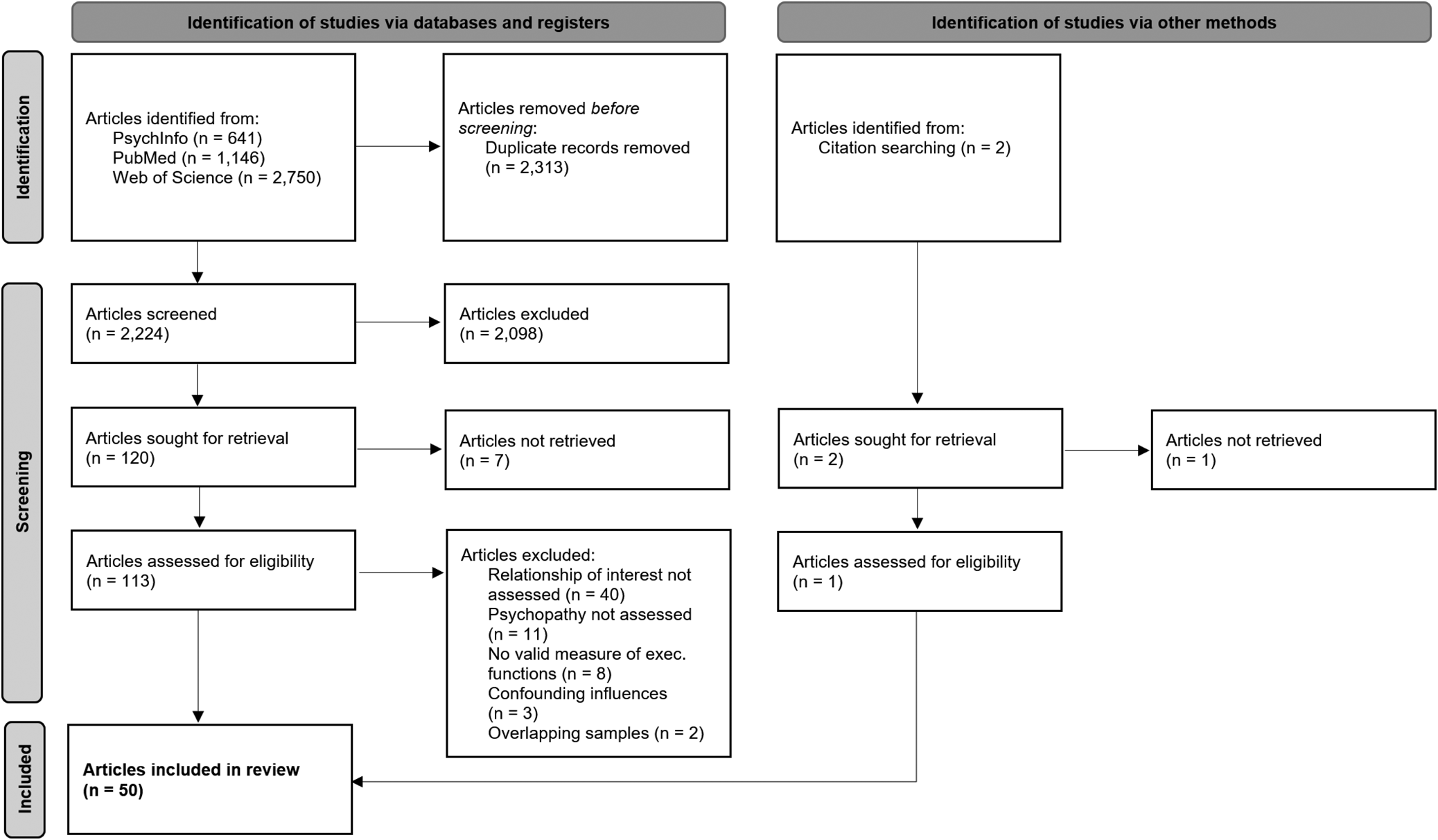

Screening was conducted in pairs of two in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA; Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow and Moher2021). The eligible literature was first manually screened at the abstract level and subsequently assessed in full. Data extraction was also performed by two independent reviewers.

Included measures

Executive functions

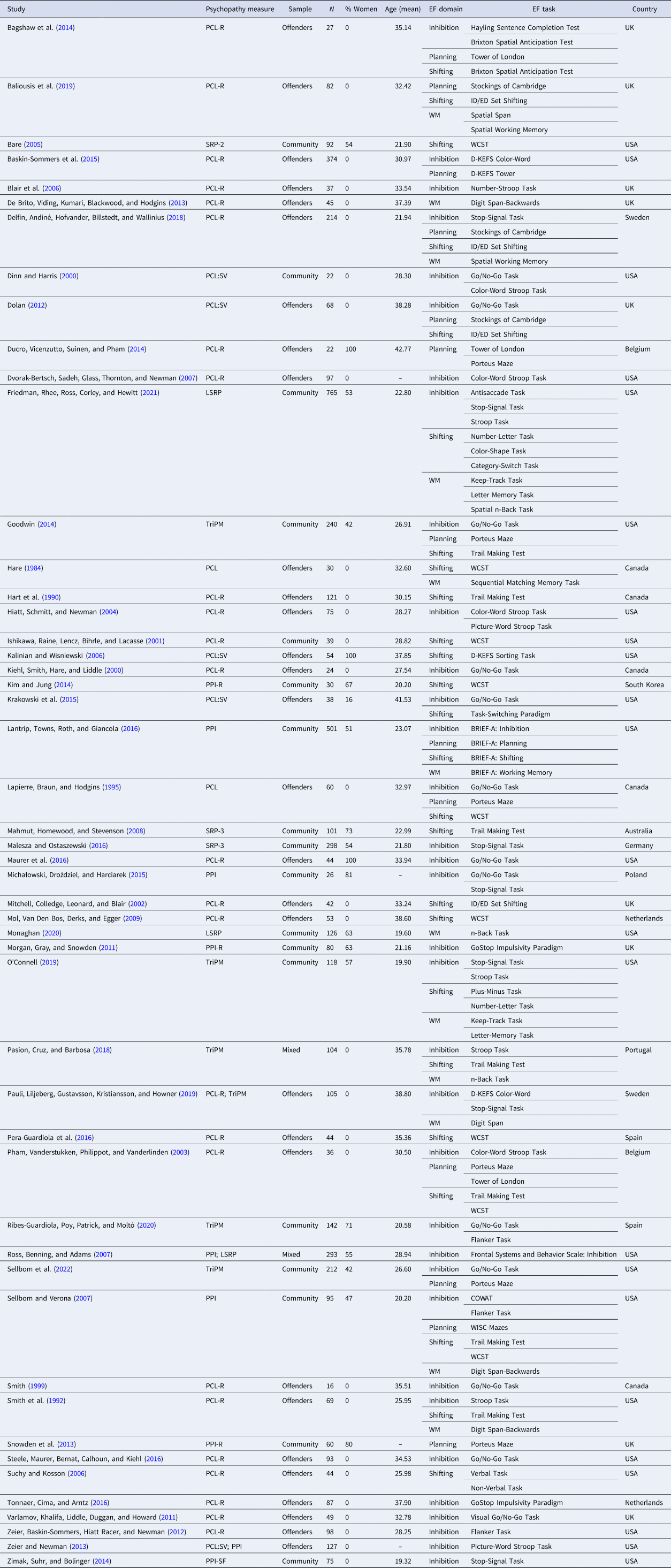

All neuropsychological tests that could be assigned to one of the following four EF domains were included: Inhibition, shifting, planning, and working memory. Assignment to an EF domain was done by manual annotation and was based on previous literature (e.g. Baliousis, Duggan, McCarthy, Huband, & Völlm, Reference Baliousis, Duggan, McCarthy, Huband and Völlm2019; Diamond, Reference Diamond2013; Jurado & Rosselli, Reference Jurado and Rosselli2007; Maes & Brazil, Reference Maes and Brazil2013; Pennington & Ozonoff, Reference Pennington and Ozonoff1996). The EF domain to which each task was assigned is shown in Table 1. We acknowledge that the grouping of specific tasks into a single domain is debatable, as many tests likely require multiple EFs simultaneously (Friedman & Miyake, Reference Friedman and Miyake2017; Karr et al., Reference Karr, Areshenkoff, Rast, Hofer, Iverson and Garcia-Barrera2018; Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000). However, in the absence of a clear definition, we addressed this issue in three ways. First, we also combined all tasks into a single common EF domain. Second, we performed supplementary analyses for the EF tasks separately. While this reduces statistical power, it avoids the ‘over-lumping’ of tasks (Snyder, Miyake, & Hankin, Reference Snyder, Miyake and Hankin2015). Third, we performed sensitivity analyses using the GOSH approach (Olkin, Dahabreh, & Trikalinos, Reference Olkin, Dahabreh and Trikalinos2012), which allows us to examine the robustness of the results by simulating alternative meta-analyses (see below).

Table 1. Study characteristics of all included articles

Note: BRIEF-A, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function; D-KEFS, Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; EF, executive function; LSRP, Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale; N, number of participants; PCL-R, Psychopathy Checklist – Revised; PCL:SV, Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version; PPI, Psychopathic Personality Inventory; PPI-R, Psychopathic Personality Inventory – Revised; PPI-SF, Psychopathic Personality Inventory – Short Form; SRP, Self Report Psychopathy Scale; TriPM, Triarchic Psychopathy Measure; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WM, working memory.

Also debatable is the question of which test score of a particular neuropsychological task best reflects EF performance. In case of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), for example, some researchers consider only the Preservative Error Score to be representative of shifting performance and ignore all other test scores produced by the WCST (e.g. Categories Achieved). However, since there is no consensus in the scientific community and test results reported in each article vary widely, we chose to extract all available data and perform our analyses incorporating all performance scores.

Moreover, only cold EF tasks were included to assess EF performance without the potentially influencing affective and reward/punishment components of hot EF tasks (Salehinejad, Ghanavati, Rashid, & Nitsche, Reference Salehinejad, Ghanavati, Rashid and Nitsche2021).

Psychopathy

Both semi-structured interviews, such as the PCL-R, as well as self-report measures were considered eligible. When available, total and factor/facet scores were extracted. However, given the large heterogeneity in the factor structure of different psychopathy measures, we followed the approach of Gillespie et al. (Reference Gillespie, Lee, Williams and Jones2022) and assigned each psychopathy factor/facet to one of two overarching factors: Interpersonal/Affective (I/A) and Lifestyle/Antisocial (L/A; for more details, see online Supplementary Table S2). These were then used to examine differences in EF performance across psychopathy factors. Importantly, although this approach increases statistical power, it has drawbacks that must be addressed. Grouping different dimensions of psychopathy into overarching factors may bias the results, especially in relation to the TriPM and the PPI-R. Both emphasize boldness and fearlessness in their conceptualization of psychopathy. While these traits are captured by Factor 1 of the PCL-R, this is only true to some extent (Venables et al., Reference Venables, Hall and Patrick2014). Moreover, boldness has been shown to have adaptive features and often displays opposite relationships with various outcomes compared to other psychopathy traits (e.g. Burghart, Sahm, Schmidt, Bulla, & Mier, Reference Burghart, Sahm, Schmidt, Bulla and Mier2024; Segarra, Poy, Branchadell, Ribes-Guardiola, & Moltó, Reference Segarra, Poy, Branchadell, Ribes-Guardiola and Moltó2022). It is therefore crucial not only to rely on the approach of Gillespie et al. (Reference Gillespie, Lee, Williams and Jones2022), but also to present results for 2-factor and 3-factor solutions separately. Given the reduced power associated with this approach, interpretation should prioritize effect sizes over statistical significance.

Synthesis of results

Cohen's d (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988) was chosen as the effect size index, with d < 0 indicating poorer EF performance in psychopathic individuals. In cases where a correlation coefficient was reported, it was converted following the formula recommended by Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, and Rothstein (Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2009). Effect sizes were pooled separately for overall EF (i.e. including all effect sizes), inhibition, shifting, planning, and working memory using multilevel random-effects models. This allows for non-independence across effect sizes (e.g. due to studies providing more than one effect size) by decomposing heterogeneity within (σ 22) and between samples (σ 12; Cheung, Reference Cheung2014). All analyses were performed in R with the metafor package (Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010). Our data can be found online: https://osf.io/fv8d5/.

Multilevel mixed-effects models were used to test whether the results were influenced by a range of potential moderators previously examined in other meta-analyses on psychopathy (Gillespie et al., Reference Gillespie, Lee, Williams and Jones2022). These included sample type (community v. offenders), percentage of women in a sample (ranging from 0 to 100%), mean age of a sample, literature status (peer reviewed v. gray), publication year, and country. The type of psychopathy measure (PCL-R v. self-report) was confounded with sample type and could therefore not be investigated.

To examine the robustness of our results, additional sensitivity analyses were performed and the presence of publication bias was investigated. The former involved GOSH analyses for overall EF and the four domains, in which one million meta-analyses were simulated based on random subsets of effect sizes (Olkin et al., Reference Olkin, Dahabreh and Trikalinos2012). The produced distribution of meta-analytical results was then plotted and visually examined. Our findings were considered robust when unimodal distributions were observed, indicating that there is no specific combination of effect sizes that drive the results in a particular direction. Conversely, multimodal distributions would suggest that certain combinations of effect sizes significantly influence the results. Lastly, the presence of publication bias was evaluated by visually inspecting colored funnel plots for asymmetry (Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Lagisz, Jennions, Koricheva, Noble, Parker and O'Dea2022) and by performing adjusted Egger's regression tests for dependent effect sizes (Rodgers & Pustejovsky, Reference Rodgers and Pustejovsky2021).

Results

Description of included studies

The literature search yielded 789 articles, of which 50 were included in our meta-analysis (Fig. 1). These were published between the years of 1984 and 2021 and comprised a total of 5694 participants (range = 16 to 765) from 12 countries. Most studies examined men, and only about a quarter of all participants were women. While 30 articles were based on individuals who offended, 20 included community samples. Detailed information on all included articles is provided in Table 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of our study selection process.

Meta-analytical results

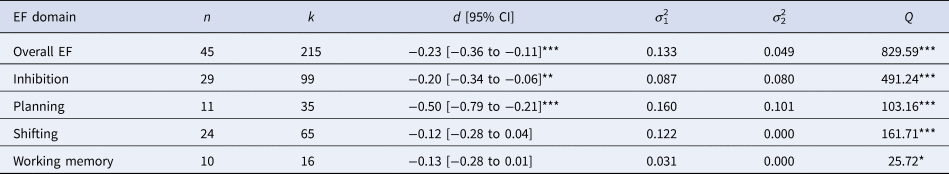

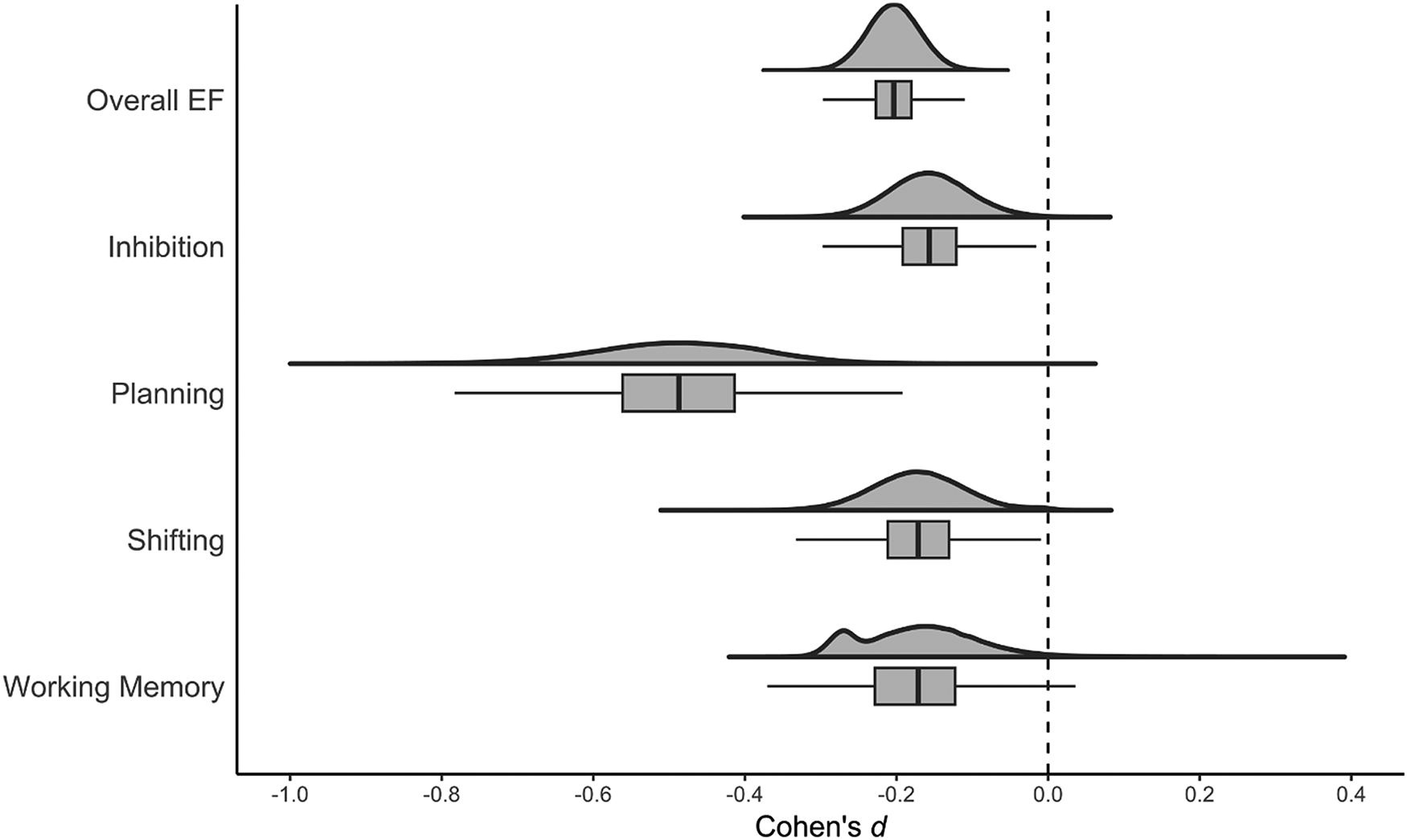

Psychopathic individuals showed statistically significant impairments in their overall EF, inhibition, and planning performance. The pooled effect sizes for shifting and working memory also indicated deficits but did not reach statistical significance. All multilevel models revealed substantial levels of heterogeneity across studies, suggesting the presence of moderators. Results are presented in Table 2 (results for individual EF tasks are shown in online Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2. Results of multilevel models (Cohen's d) for each executive function domain

Note: EF, executive function; n, number of studies; k, number of effect sizes; d, Cohen's d; CI, confidence interval; σ 21, between-study heterogeneity; σ 22, within-study heterogeneity; Q, test for heterogeneity.

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

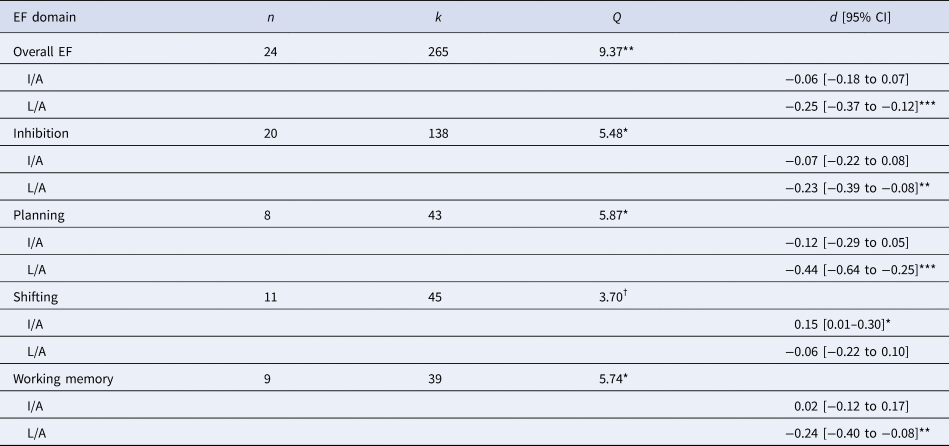

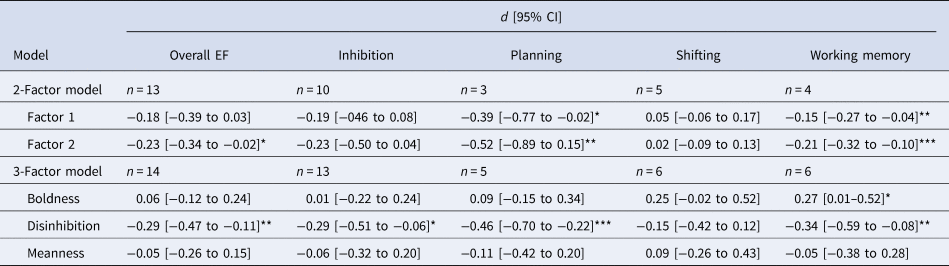

Analyses of differences in EF performance across psychopathy factors yielded statistically significant results for overall EF, inhibition, planning, and working memory (Table 3). Across four domains, L/A was associated with significantly greater deficits than I/A. The contrary was found for shifting, although the Q-test was only marginally significant (p = 0.05; Table 3). Here, I/A was associated with improved shifting performance, whereas L/A resulted in a null effect. When the psychopathy factors were further disentangled, the PCL-like 2-factor model (i.e. excluding TriPM and PPI-R) resulted in less clear differences for factor 1 and factor 2 than the overarching factor model for L/A and I/A. Nevertheless, factor 2 generally displayed larger negative effect sizes than factor 1 (Table 4). In contrast, in the 3-factor model, disinhibition was consistently associated with deficits across all EF domains, whereas boldness exhibited either no deficits (overall EF, inhibition, planning) or even improved performance (shifting and working memory; Table 4). Due to low statistical power, the confidence intervals were large (Table 4).

Table 3. Differences in executive function performance (Cohen's d) across psychopathy factors (grouped to two overarching factors)

Note: EF, executive function; n, number of studies; k, number of effect sizes; d, Cohen's d; CI, confidence interval; I/A, Interpersonal/Affective; L/A, Lifestyle/Antisocial; Q, test for heterogeneity (indicates whether the difference between I/A and L/A is statistically significant).

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; † p = 0.05.

Table 4. Differences in executive function performance (Cohen's d) across psychopathy factors (using 2-factor and 3-factor models)

Note: EF, executive function; n, number of studies; d, Cohen's d; CI, confidence interval. The 2-factor model includes all PCL-like measures, while the 3-factor model includes only the TriPM and the PPI-R. For the sake of brevity, the factors presented in the table are named Boldness, Disinhibition, and Meanness, but these also represent the PPI-R's Fearless Dominance, Self-Centered Impulsivity, and Coldheartedness, respectively. *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

Moderator analyses

The proportion of women in a sample significantly moderated overall EF (Q = 17.62, p < 0.05, β = −0.72 [−1.05 to −0.38]), inhibition (Q = 3.86, p < 0.05, β = −0.52 [−1.04 to −0.001]), planning (Q = 4.59, p < 0.05, β = −0.78 [−1.50 to −0.07]), and shifting (Q = 4.70, p < 0.05, β = −0.52 [−1.00 to −0.05]), with more women producing greater performance deficits in psychopathy. However, this was not observed for working memory (Q = 0.84, p = 0.36, β = −0.26 [−0.81 to 0.30]). All other tested moderators (i.e. sample type, age, literature status, publication year, and country) were statistically non-significant.

Sensitivity analyses and publication bias

Except for working memory, our GOSH sensitivity analyses identified unimodal distributions for all EF domains, indicating that no combination of effect sizes biases the results in any particular direction (Fig. 2). The distribution for working memory was bimodal, with the effects reported by Baliousis et al. (Reference Baliousis, Duggan, McCarthy, Huband and Völlm2019) having the largest influence. Specifically, meta-analyses that include them generally yield smaller summary effect sizes (i.e. the right peak; Figure 2). However, the proximity of the two peaks suggests that the differences are negligible.

Figure 2. Distribution of summary effect sizes based on meta-analyses with randomly drawn subsets of effect sizes.

Note: The results are based on a graphical display of study heterogeneity (GOSH) approach, in which separate meta-analyses are performed on 1 000 000 randomly drawn subsets of effect sizes. Due to the smaller number of effect sizes for working memory (k = 16), all possible combinations were fitted (216–1 = 65 535). It is important to emphasize that this method does not account for dependencies between effect sizes and should therefore only be interpreted in terms of the robustness of the results, rather than providing information about the true summary effect size of each EF domain.

Online Supplementary Fig. S1 shows a colored funnel plot for each EF domain. A visual inspection of these funnel plots reveals a clear pattern of asymmetry for overall EF and planning. This is supported by statistically significant Egger's regression tests indicating the presence of small study effects. Consequently, the true pooled effect size for overall EF and planning are likely smaller.

Discussion

This meta-analysis shows statistically significant impairments in overall EF, inhibition, and planning performance among individuals with psychopathic traits. These deficits are consistent with current conceptualizations of psychopathy that emphasize symptoms of poor behavioral control and difficulty planning ahead (Hare, Reference Hare, Felthous and Saß2020). Both are likely to foster socially distressing and inappropriate behaviors such as aggression and violence (Hare, Reference Hare, Felthous and Saß2020; Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Arseneault, Belsky, Dickson, Hancox, Harrington and Caspi2011). However, it is important to highlight that the effects in our meta-analysis can only be considered small. Although the pooled effect size for planning is of medium size, it was clearly influenced by publication bias and thus is likely smaller in reality (Thornton, Reference Thornton2000). Together with the lack of statistically significant effects for working memory and shifting performance, it can be concluded that psychopathy is not characterized by severe global EF dysfunction and that EF impairments are not a key feature of this disorder.

Instead, it can be assumed that EF dysfunctions are related to antisociality and not to psychopathic personality traits per se (O'Connell, Reference O'Connell2019). This is supported by Jansen and Franse (Reference Jansen and Franse2024), who meta-analyzed EF deficits in ASPD. Their summary effect sizes were approximately twice as large as those identified in our own meta-analysis, suggesting that EF deficits play a greater role in ASPD than they do in psychopathy. Our findings regarding differences in EF performance across psychopathy factors further support this conclusion. We found statistically significant EF impairments for L/A, but not for I/A. This is also true for working memory performance, which did not appear to be impaired in psychopathy when only total scores were considered. While such a clear distinction between the two psychopathy factors was not readily apparent when only PCL-like scales were examined, the results for the 3-factor model of psychopathy (i.e. TriPM and PPI-R) showed a clear pattern. Disinhibition (and meanness) was consistently related to deficits in all EF domains, whereas boldness exhibited either no relationship or even positive associations with EF performance. Crucially, traits of disinhibition are highly shared between ASPD and psychopathy. Boldness, on the other hand, is unique to psychopathy and serves as a key distinguishing factor from ASPD (Venables et al., Reference Venables, Hall and Patrick2014; Wall, Wygant, & Sellbom, Reference Wall, Wygant and Sellbom2015). It is therefore likely that the additional presence of boldness in psychopathy attenuates EF impairments, thereby making them less pronounced than in ASPD.

Our moderator analyses suggest that overall EF, inhibition, planning, and shifting deficits in psychopathy are greater among women than men. Although no such influence of sex was found for working memory performance, this should not be taken as evidence for the absence of this moderating effect. Especially because the sample of studies that examined working memory performance was small and included few women. Female psychopathy differs from male psychopathy (Guay, Knight, Ruscio, & Hare, Reference Guay, Knight, Ruscio and Hare2018) with differences particularly evident in greater emotional instability (Beryl, Chou, & Völlm, Reference Beryl, Chou and Völlm2014). This instability may manifest in more EF impairments and thus explain the findings of our moderator analyses. Further research is needed to test this hypothesis.

Integration of neuroimaging studies

Integrating neuroimaging studies in our findings can provide additional insight into why EF impairments do not appear to be a prominent feature of psychopathy per se, but rather are related to the disinhibitory and antisocial aspects of this disorder. For example, a meta-analysis by Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Sid, Wensing, Eickhoff, Habel, Gur and Nickl-Jockschat2019) explored the neural network of aggression, a behavior closely tied to disinhibition. Their findings revealed a link between aggression and aberrant precuneus activity, which is assumed to further disrupt the larger cognitive control network and in turn negatively impacts EF performance. Similarly, Dugré et al. (Reference Dugré, Radua, Carignan-Allard, Dumais, Rubia and Potvin2020) conducted a meta-analysis of neurofunctional abnormalities within the antisocial spectrum across five different neurocognitive domains. One of these domains was cognitive control (i.e. EF performance), with studies primarily using Stroop and Go/No-Go tasks. Their results again indicated reduced activation in regions within (and outside) the cognitive control network, including the premotor cortex, anterior insula, ventrolateral PFC, and cerebellar regions.

Considering these findings, alongside the fact that most individuals with psychopathy also meet diagnostic criteria for ASPD (Hildebrand & de Ruiter, Reference Hildebrand and de Ruiter2004), the question arises as to why psychopathy does not appear to be characterized by substantial EF impairments. Another meta-analysis by Alegria et al. (Reference Alegria, Radua and Rubia2016) may provide answers. The authors aggregated whole-brain fMRI studies involving youths with disruptive behavior disorder or conduct problems. Consistent with Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Sid, Wensing, Eickhoff, Habel, Gur and Nickl-Jockschat2019) and Dugré et al. (Reference Dugré, Radua, Carignan-Allard, Dumais, Rubia and Potvin2020), they identified deficiencies in a broader network of prefrontal and other regions (i.e. rostro-dorsomedial, fronto-cingulate, and ventral-striatal cortices). More importantly, however, a subgroup analysis focusing specifically on youths with additional psychopathic traits revealed a different pattern of results. They displayed hypoactivity in the ventromedial PFC and limbic system, but hyperactivity in dorsal and fronto-striatal regions, which might lead to unimpaired executive control. It follows that while psychopathy shares many neurobiological features with ASPD as well as with disruptive or aggressive behavior, it is related to additional unique adaptive aspects that are observable on a neural level and seem to mitigate EF impairments otherwise prevalent in related conditions. This mirrors our own findings. Specifically, poor EF performance correlated strongly with psychopathic traits that are also highly prevalent in ASPD (i.e. L/A or disinhibition), but showed weaker relationships with traits more distinctive of psychopathy (i.e. I/A or boldness) and potentially adaptive under certain conditions (Bronchain, Raynal, & Chabrol, Reference Bronchain, Raynal and Chabrol2020). This likely accounts for the overall minor role of EF impairments within psychopathy itself. That said, to truly advance our understanding of the underlying roots of these adaptive traits, future neuroimaging studies need to disentangle psychopathy into its factors instead of treating it as a single construct.

Limitations

A few limitations must be considered when interpreting our results. First and foremost, although we drew on previous research to assign neuropsychological tasks to specific EF domains, we cannot rule out that these tasks actually reflect performance in more than one domain (Niendam et al., Reference Niendam, Laird, Ray, Dean, Glahn and Carter2012). This is known as the impurity problem of EFs (Baggetta & Alexander, Reference Baggetta and Alexander2016; Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000). There have been attempts in the past to resolve this issue by using so-called process pure measures of EFs, which are assumed to be uniquely associated with a single EF domain (Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter and Wager2000; O'Connell, Reference O'Connell2019). However, the current state of evidence for this assumption is weak. We therefore applied several strategies to mitigate the potential influence of our task-domain assignment. These included exploring results based on a common EF domain as well as for individual tasks independently, and using GOSH sensitivity analyses. All of which support the robustness of our findings and provide strong evidence that our conclusions are not biased by the assumptions we made.

Another limitation arises from the fact that the vast majority of studies included in this meta-analysis focused on men. This is particularly troublesome in view of the results of our moderator analyses, but unfortunately a common theme in the literature that has already affected the generalizability of other meta-analyses (e.g. Burghart et al., Reference Burghart, de Ruiter, Hynes, Krishnan, Levtova and Uyar2023; de Ruiter et al., Reference de Ruiter, Burghart, De Silva, Griesbeck Garcia, Mian, Walshe and Zouharova2022). Future studies in the field should therefore prioritize the inclusion of women.

Implications

The present findings have implications for both future research and treatment efforts. First, it should become standard practice in psychopathy research to investigate and report psychopathy factors, not just total scores. As shown in our meta-analysis, this may help to clarify conflicting results. Second, neuroimaging studies that map the neural correlates of EFs for different psychopathy factors are needed, as are studies that directly compare psychopathic individuals' performance on hot and cold EF tasks. Particularly in regard of the known aberrations in structural connectivity between the orbital parts of the prefrontal cortex and medial temporal lobe in psychopathy (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Catani, Deeley, Latham, Daly, Kanaan and Murphy2009), it could be predicted that hot EF tasks result in stronger impairments in psychopathy. Further, the inhibition impairments should be associated by dysfunctional activation in prefrontal regions and might be related to emotion regulation deficits. However, studies on emotion regulation in psychopathy are still rather scarce and findings on fractional anisotropy in psychopathy vary between psychopathy factors and between studies with conduct disorder and adult psychopathy (e.g. Maurer, Paul, Anderson, Nyalakanti, & Kiehl, Reference Maurer, Paul, Anderson, Nyalakanti and Kiehl2020; Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Pujara, Motzkin, Newman, Kiehl, Decety and Koenigs2015), hampering clear hypotheses on the direction of change.

Finally, although there is ample evidence that poor EF performance can be improved with treatment (Stamenova & Levine, Reference Stamenova and Levine2019), our results suggest that EF training should not be blindly administered to psychopathic individuals. Rather, it should be reserved for those who score high on antisocial factors (e.g. disinhibition). Especially with regard to the importance of cost-efficient therapy, this can help to allocate resources more effectively.

Conclusion

With the present meta-analysis, we showed that EF deficits are rather small and may not represent a central aspect of general psychopathy. That is, performance impairments on various EF tasks seem specific to the antisocial and disinhibitory traits of psychopathy, whereas the affective traits that are more distinctive of psychopathy, such as boldness, relate to no or even enhanced EF performance. Our findings have clear implications for future research on EFs in psychopathy and highlight the necessity to address psychopathy not as a single construct, but to systematically differentiate between the affective and the antisocial dimensions of this disorder.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724001259.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.